Abstract

We report a concise, enantioselective total synthesis of (−)-taiwaniaquinone H and the first enantioselective total synthesis of (−)-taiwaniaquinol B by a route that includes enantioselective, palladium-catalyzed α-arylation of a ketone with an aryl bromide that was generated by sterically controlled halogenation via iridium-catalyzed C–H borylation. This asymmetric α-arylation creates the benzylic, quaternary stereogenic center present in the taiwaniaquinoids. The synthesis was completed efficiently by developing a Lewis acid-promoted cascade to construct the [6,5,6] tricyclic core of an intermediate common to the synthesis of a number of taiwaniaquinoids. Through the preparation of these compounds, we demonstrate the utility of constructing benzylic, quaternary, stereogenic centers, even those lacking a carbonyl group in the α-position, by asymmetric α-arylation.

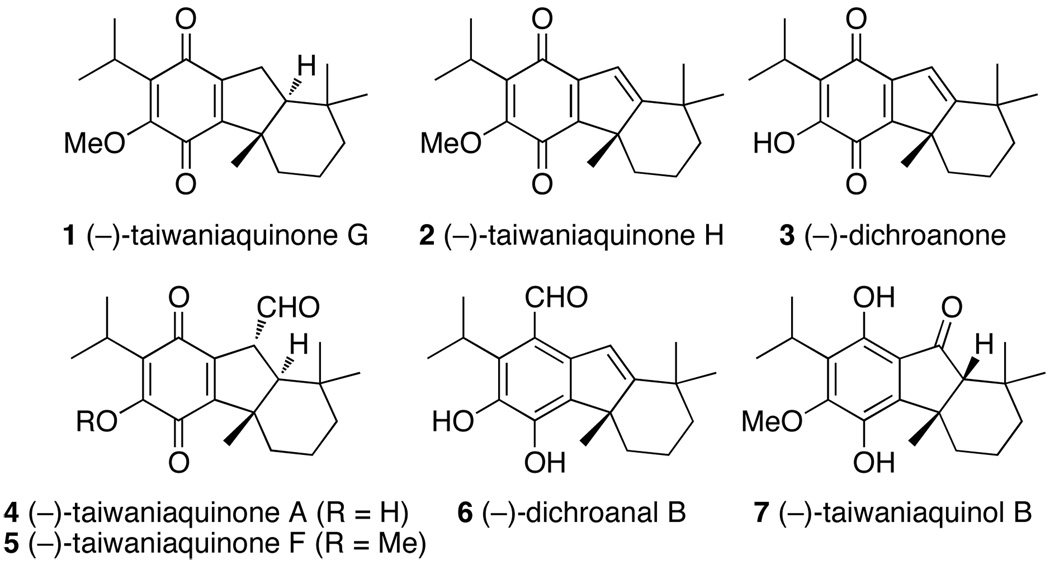

The taiwaniaquinoids are a family of unusual diterpenoids possessing a [6,5,6]-abeo-abietane skeleton that was unknown in nature prior to 1995.1–7 Each member of this family contains a benzylic quaternary stereogenic center (Figure 1). Studies of the biological activities of taiwaniaquinoids are ongoing, but preliminary data have indicated that some members of this family exhibit antitumor activities.8–11 The structural features and the biological activities of these compounds have led many groups to report total and formal syntheses of the taiwaniaquinoids.11–25 However, the majority of these syntheses have targeted racemic versions of this class of natural products.

Figure 1.

Representative taiwaniaquinoids.

Asymmetric syntheses of the taiwaniaquinoids are challenging due to the limited number of enantioselective reactions that establish quaternary stereogenic centers.26–29 One approach that eliminates this challenge is to prepare the material by a ring-contractive derivatization of enantioenriched terpenes. Alvarez-Manzaneda and co-workers prepared (−)-taiwaniaquinone G (1),22 (−)-taiwaniaquinone H (2) and (−)-dichroanone (3) in 15 or 16 steps from (+)-sclareolide,23 and Gademann and coworkers prepared (−)-taiwaniaquinone H (2) in 13 steps from methyl dehydroabiate.25 Recently, Alvarez-Manzaneda and co-workers reported the syntheses of (−)-taiwaniaquinone A (4) in 15 steps and (−)-taiwaniaquinone F (5) in 16 steps from (+)-podocarpa-8(14)-en-13-one.30 To date, only two enantioselective total syntheses of taiwaniaquinoids from achiral or racemic starting materials have been reported. McFadden and Stoltz reported an 11-step synthesis of (+)-dichroanone (ent-3) in which the quaternary stereogenic center was set by an asymmetric Tsuji allylation.17 Recently, Node and coworkers employed an enantioselective, intramolecular Heck reaction for the total syntheses of (−)-dichroanal B (6) in 12 steps, (−)-dichroanone (3) in 14 steps, and (−)-taiwaniaquinone H (2) in 15 steps beginning with a tetrasubstituted arene.24

Previously, our group reported the asymmetric α-arylation of ketones to form products containing quaternary benzylic stereogenic centers.31 Although the taiwainaquinoids do not contain a carbonyl group α to the benzylic stereogenic center, we envisioned that asymmetric α-arylation could be used to construct this center and that the ketone function could be integral to creation of the [6,5,6] tricyclic core. Further, we envisioned that the aryl electrophile for the proposed α-arylation process could be generated from a simple arene by a sterically controlled iridium-catalyzed borylation and halogenation sequence developed by our group.32,33

Herein, we report concise, enantioselective total syntheses of (−)-taiwaniaquinone H (2) and (−)-taiwaniaquinol B (7) from simple achiral and racemic reactants through this halogenation process and an asymmetric α-arylation for the first time in the synthesis of a natural product. A Lewis acid-promoted cascade then establishes the unusual [6,5,6] tricyclic core.

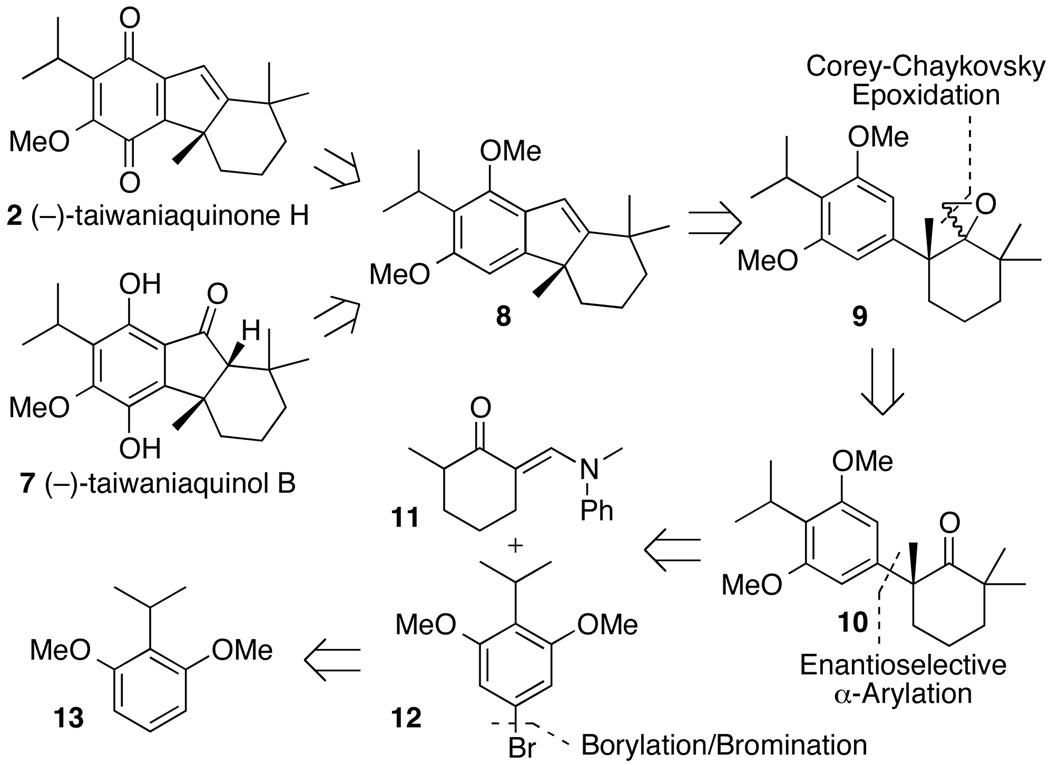

Scheme 1 illustrates the strategy we envisioned to achieve the enantioselective total syntheses of (−)-taiwaniaquinone H (2) and (−)-taiwaniaquinol B (7). Both molecules would be accessible from the same intermediate, tetrahydrofluorene 8, by oxidation and demethylation procedures. We considered that the tricyclic core of tetrahydrofluorene 8 could be formed from epoxide 9 by a formal intramolecular addition of the electron-rich arene ring to the epoxide unit. Epoxide 9 would be derived from α-aryl ketone 10, which would be generated by our palladium-catalyzed asymmetric α-arylation of ketones.

Scheme 1.

Retrosynthetic Analysis for the Syntheses of (−)-Taiwaniaquinone H (2) and (−)-Taiwaniaquinol B (7)

In the forward direction, the first step of the synthesis required aryl bromide 12. Under traditional conditions for electrophilic aromatic substitution, the known resorcinol derivative 1334 undergoes bromination at the position located ortho to the two methoxy groups.16 To overcome this electronic bias, we used a one-pot, two-step sequence to prepare aryl bromide 12 from 13 by the combination of a sterically controlled, iridium-catalyzed borylation and a subsequent bromination of the aryl boronate ester with copper(II) bromide (Scheme 2).32 This method provided aryl bromide 12 in 75% yield on a multi-gram scale.

Scheme 2.

One-pot Synthesis of Aryl Bromide 12a

a B2pin2 = bis(pinacolato)diboron; dtbpy = 4,4´-di-tert-butylbipyridine.

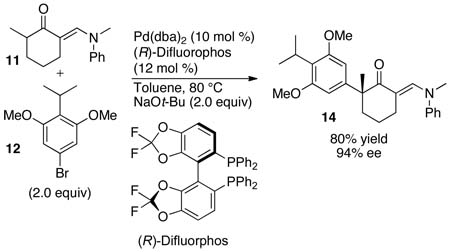

Access to aryl bromide 12 enabled us to explore the key enantioselective α-arylation. The reaction of aryl bromide 12 with 2,2,6-trimethylcyclohexanone did not generate the α-arylation product in the presence of a catalyst generated from Pd(dba)2 and (R)-Segphos or (R)-Difluorophos. However, the reaction of aryl bromide 12 with the 2-methylcyclohexanone derivative 1135,36 in the presence of 10 mol % of the combination of Pd(dba)2 and (R)-Difluorophos as catalyst formed the α-aryl ketone 14 in 80% yield with 94% ee (eq 1).37

|

(1) |

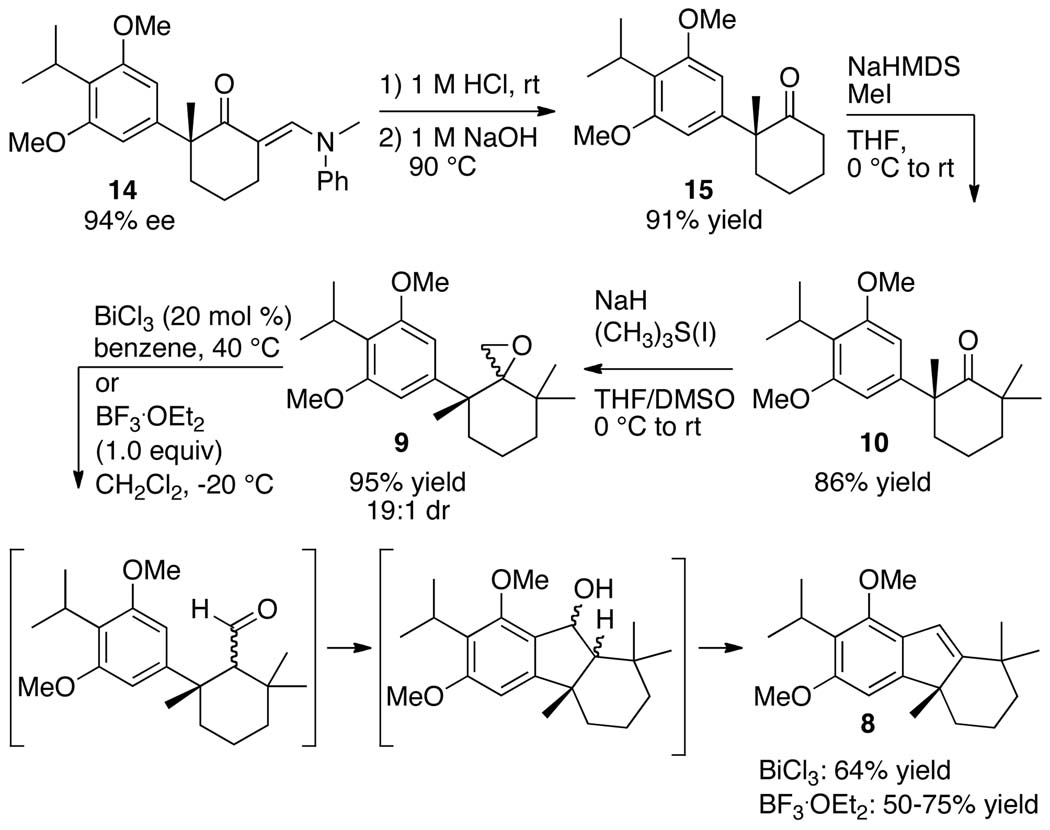

The synthesis of the key tetrahydrofluorene intermediate 8 was accomplished in five steps from enantioenriched ketone 14 (Scheme 3). Acid-promoted hydrolysis of ketone 14, followed by deformylation of the resulting β-ketoaldehyde in the presence of aqueous sodium hydroxide, provided the deprotected ketone 15 in 91% yield over two steps. Dimethylation of 15 with methyl iodide and sodium bis(trimethylsilyl)amide (NaHMDS) as the base formed the tetra-substituted cyclohexanone 10 in 86% yield.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of Tetrahydrofluorene 8

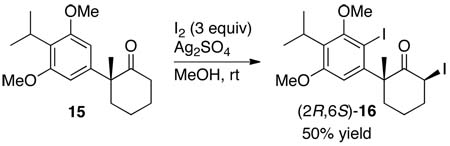

The absolute configuration of the stereogenic center in these products was established by iodination of 15. The reaction of 15 with iodine and silver sulfate formed diiodide 16 (eq 2). Single-crystal X-ray diffraction of the major diastereomer of 16 enabled the assignment of the absolute configuration as (2R,6S)-16 (see Figure S1 in the Supporting Information). Thus, the enantioselective α-arylation of ketone 11 conducted with (R)-Difluorophos and Pd(dba)2 generates (R)-14 and creates the appropriate enantiomer to prepare (−)-taiwaniaquinone H (2) and (−)-taiwaniaquinol B (7).

|

(2) |

Attempts to convert ketone 10 to epoxide 9 by Corey-Chaykovsky epoxidation with the common sulfur ylide, dimethylsulfoxonium methylide,38,39 led to recovery of 10, even under forcing conditions (80 °C). We presumed this lack of reactivity resulted from the steric hindrance surrounding the ketone functionality in 10. Thus, we attempted a Corey-Chaykovsky epoxidation of ketone 10 with the smaller and more reactive sulfur ylide, dimethylsulfonium methylide.39,40 This reaction formed epoxide 9 in 95% yield with >15:1 diastereoselectivity.

Some Lewis acids are known to promote the rearrangement of epoxides to carbonyl compounds.41–45 We tested the ability of such Lewis acids to initiate the cascade shown in Scheme 3 in which epoxide 9 would form tetrahydrofluorene 8 via rearrangement of the epoxide to the aldehyde. This aldehyde would then be attacked by the electron rich arene in the presence of a Lewis acid to form the corresponding alcohol, which could undergo elimination to form the target indene 8. After testing a series of Lewis-acid catalysts for this sequence (see the Table S1 in the Supporting Information) we found that treatment of epoxide 9 with BF3 ·OEt2 or a Bi(III) salt generated tetrahydrofluorene 8 in good yield. The cascade promoted by BF3 ·OEt2 occurred to form tetrahydrofluorene 8 in up to 75% yield; however, the yields of this reaction varied from 50–75%. Slightly lower yields were observed for the formation of tetrahydrofluorene 8 from epoxide 9 in the presence of Bi(III) salts as the Lewis acid, but this reaction was less sensitive to variations in temperature. Ultimately, we conducted this cascade promoted by 20 mol % BiCl3 to generate tetrahydrofluorene 8 in 64% yield.

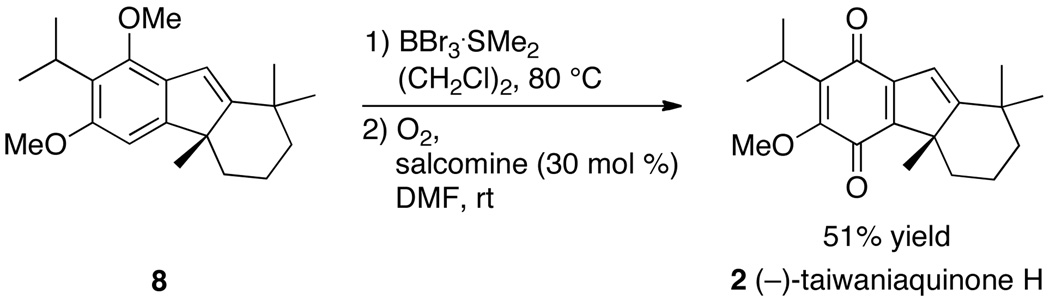

The synthesis of (−)-taiwaniaquinone H (2) was completed according to methods developed by Trauner and coworkers for the synthesis of (±)-taiwaniaquinone H.16 Selective monodemethylation of tetrahydrofluorene 8 with BBr3 ·SMe2, followed by oxidation of the resulting tetrahydrofluoren-1-ol in the presence of salcomine formed (−)-taiwaniaquinone H (2) in 51% yield over two steps (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of (−)-Taiwaniaquinone H (2)a

a Salcomine = (N,N´-bis(salicylidene)ethylenediaminocobalt (II).

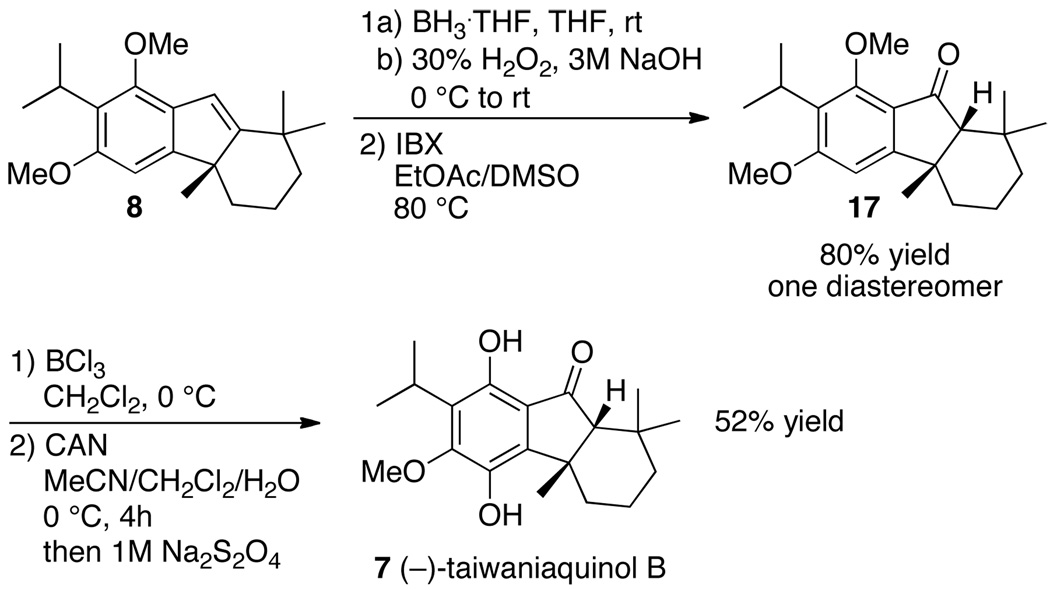

Tetrahydrofluorene 8 is also a suitable intermediate for the synthesis of (−)-taiwaniaquinol B (7). The enantioselective total synthesis of (−)-taiwaniaquinol B was completed in four steps from tetrahydrofluorene 8 (Scheme 5). Hydroboration of 8, followed by oxidation of the resulting alkylborane in the presence of basic hydrogen peroxide formed a diastereomeric mixture of hexahydrofluoren-9-ols. Oxidation of these alcohols with 2-iodoxybenzoic acid (IBX) gave tetrahydrofluoren-9-one 17 as a single diastereomer in 80% yield. Tetrahydrofluoren-9-one 17 was converted to (−)-taiwaniaquinol B according to procedures reported by Fillion13 and Trauner16 for syntheses of racemic taiwaniaquinol B. Selective monodemethylation of 17 with BCl3, oxidation of the resulting 8-hydroxyfluoren-9-one intermediate with cerric ammonium nitrate (CAN), and reductive workup with sodium dithionite gave (−)-taiwaniaquinol B in 52% yield over two steps.

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of (−)-Taiwaniaquinol B (7)

In summary, an enantioselective total synthesis of (−)-taiwaniaquinone H was accomplished in 14.6% overall yield in just 10 steps, and the first enantioselective total synthesis of (−)-taiwaniaquinol B was completed in 11.9% overall yield in just 12 steps. Two catalytic protocols reported by our group, a one-pot meta bromination of 2-isopropyl-1,3-dimethoxybenzene by iridium-catalyzed borylation followed by copper-mediated bromination of the resulting arylboronate ester, and a palladium-catalyzed, enantioselective α-arylation, were used in early steps on multi-mmol scales. The synthesis was completed efficiently by developing a Lewis acid-promoted cascade to construct the [6,5,6] tricyclic core of an intermediate common to the synthesis of a number of taiwaniaquinoids. Finally, we wish to emphasize that the quaternary stereogenic center in the taiwaniquinoids bears no carbonyl group in the α-position, but is readily set by the asymmetric α-arylation, and the ketone functionality serves as a key point of reaction to complete the syntheses. Thus, the enantioselective α-arylation of ketones should be considered as a strategic method to establish quaternary benzylic stereogenic centers for complex-molecule synthesis. Further studies to increase the scope of this enantioselective process are ongoing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank the NIH for financial support of this work (GM-58108 to J.F.H. and GM84584 to L.M.S.), Zhijian Liu for contributions to early steps in the synthesis, Johnson-Matthey for gifts of iridium and palladium salts, and Allychem and BASF for gifts of bis(pinacolato)diboron.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental details, characterization data, and 1H and 13C NMR spectra. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Majetich G, Shimkus JM. J. Nat. Prod. 2010;73:284. doi: 10.1021/np9004695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin WH, Fang JM, Cheng YS. Phytochemistry. 1995;40:871. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin WH, Fang JM, Cheng YS. Phytochemistry. 1996;42:1657. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawazoe K, Yamamoto M, Takaishi Y, Honda G, Fujita T, Sezik E, Yesilada E. Phytochemistry. 1999;50:493. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ohtsu H, Iwamoto M, Ohishi H, Matsunaga S, Tanaka R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:6419. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang CI, Chien SC, Lee SM, Kuo YH. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2003;51:1420. doi: 10.1248/cpb.51.1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang CI, Chang JY, Kuo CC, Pan WY, Kuo YH. Planta Med. 2005;71:72. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-837754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iwamoto M, Ohtsu H, Tokuda H, Nishino H, Matsunaga S, Tanaka R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2001;9:1911. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minami T, Iwamoto M, Ohtsu H, Ohishi H, Tanaka R, Yoshitake A. Planta Med. 2002;68:742. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-33787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanson JR. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2004;21:312. doi: 10.1039/b300377a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katoh T, Akagi T, Noguchi C, Kajimoto T, Node M, Tanaka R, Nishizawa M, Ohtsu H, Suzuki N, Saito K. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007;15:2736. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banerjee M, Mukhopadhyay R, Achari B, Banerjee AK. Org. Lett. 2003;5:3931. doi: 10.1021/ol035506b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fillion E, Fishlock D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13144. doi: 10.1021/ja054447p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Banerjee M, Mukhopadhyay R, Achari B, Banerjee AK. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:2787. doi: 10.1021/jo052589w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Planas L, Mogi M, Takita H, Kajimoto T, Node M. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:2896. doi: 10.1021/jo052454q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang GX, Xu Y, Seiple IB, Trauner D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:11022. doi: 10.1021/ja062505g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McFadden RM, Stoltz BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:7738. doi: 10.1021/ja061853f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li SL, Chiu P. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:1741. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tang SC, Xu YF, He JM, He YP, Zheng JY, Pan XF, She XG. Org. Lett. 2008;10:1855. doi: 10.1021/ol800513v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Majetich G, Shimkus JM. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:3311. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alvarez-Manzaneda E, Chahboun R, Cabrera E, Alvarez E, Alvarez-Manzaneda R, Meneses R, Es-Samti H, Fernandez A. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:3384. doi: 10.1021/jo900153y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alvarez-Manzaneda E, Chahboun R, Cabrera E, Alvarez E, Haidour A, Ramos JM, Alvarez-Manzaneda R, Hmamouchi M, Es-Samti H. Chem. Commun. 2009;592 doi: 10.1039/b816812a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alvarez-Manzaneda E, Chahboun R, Cabrera E, Alvarez E, Haidour A, Ramos JM, Alvarez-Manzaneda R, Charrah Y, Es-Samti H. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009;7:5146. doi: 10.1039/b916209g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Node M, Ozeki M, Planas L, Nakano M, Takita H, Mori D, Tamatani S, Kajimoto T. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:190. doi: 10.1021/jo901972b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jana CK, Scopelliti R, Gademann K. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:7692. doi: 10.1002/chem.201001085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quaternary Stereocenters. Challenges and Solutions in Organic Synthesis. Wiley-VCH: Weinheim; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trost BM, Jiang CH. Synthesis. 2006;369 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christoffers J, Baro A. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2005;347:1473. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Douglas CJ, Overman LE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:5363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307113101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alvarez-Manzaneda ECR, Alvarez E, Tapia R, Alvarez-Manzaneda R. Chem. Commun. 2010:9244. doi: 10.1039/c0cc03763j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liao XB, Weng ZQ, Hartwig JF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:195. doi: 10.1021/ja074453g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murphy JM, Liao X, Hartwig JF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:15434. doi: 10.1021/ja076498n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mkhalid IAI, Barnard JH, Marder TB, Murphy JM, Hartwig JF. Chem. Rev. 2010:890. doi: 10.1021/cr900206p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Engler TA, Sampath U, Naganathan S, Velde DV, Takusagawa F, Yohannes D. J. Org. Chem. 1989;54:5712. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chieffi A, Kamikawa K, Ahman J, Fox JM, Buchwald SL. Org. Lett. 2001;3:1897. doi: 10.1021/ol0159470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woodward RB, Sondheimer F, Taub D, Heusler K, McLamore WM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1952;74:4223. [Google Scholar]

- 37. . [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corey EJ, Chaykovsky M. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1962;84:867. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Corey EJ, Chaykovsky M. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1965;87:1353. doi: 10.1021/ja01089a055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Corey EJ, Chaykovsky M. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1962;84:3782. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rickborn B. In: Comprehensive Organic Synthesis. Trost BM, editor. Vol. 3. Pergamon: Oxford; 1991. p. 733. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ranu BC, Jana U. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:8212. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sudha R, Narasimhan KM, Saraswathy VG, Sankararaman S. J. Org. Chem. 1996;61:1877. doi: 10.1021/jo951839d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maruoka K, Murase N, Bureau R, Ooi T, Yamamoto H. Tetrahedron. 1994;50:3663. [Google Scholar]

- 45.House HO. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1955;77:3070. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.