Abstract

In recent years, complementary and alternative medicine modalities, including acupuncture, have been incorporated intohospice careboth to address symptom distress and to enhance quality of life. Beginning in 1997, Kaiser Permanente Northwest Hospice began offering limited acupuncture services to hospice patients and, in some cases, their caregivers. Data collection—comprising a chart review (n = 71) and in-depth interviews with the two program acupuncturists—was initiated to explore in a preliminary fashion both the processes involved in acupuncture delivery and outcomes associated with this intervention. Information culled from the patient charts (representing the year 2003) revealed a median age of 68.5 years, a cancer diagnosis in 63% of cases, and a median hospice length of stay of 102 days. The most commonly cited chief complaints presented to the acupuncturists included pain (70%), anxiety (45%), shortness of breath (27%), and nausea/vomiting (14%). Patients received a median of three acupuncture treatments; excellent or good results were noted in the charts of 34% of patients whose chief complaint was pain, in 31% of anxiety chief complaints, in 22% of shortness-of-breath chief complaints, and in 29% for nausea/vomiting chief complaints. The program acupuncturists described their practice with this group of patients as a departure from how they treat patients in a typical practice context. They described a greater focus on providing comfort through ameliorating symptoms and a diminished focus on more holistic goals, which often are typical elements in an acupuncture intervention. Nonetheless, acupuncturists also observed instances of outcomes in psychologic, social, and spiritual domains, regardless of whether these outcomes were the principal focus of treatment. These data add to the accumulating anecdotal reports suggesting that acupuncture is a promising adjunctive therapy for those nearing the end of life in the home hospice setting. More in-depth and precise assessment is warranted to comprehensively evaluate acupuncture as a viable adjunct to current usual and customary hospice care.

Introduction

Increasingly, complementary and alternative medicine modalities, including acupuncture, massage, Reiki, and music therapy, have been incorporated into hospice care to treat both terminally ill patients and their caregivers to reduce or eliminate symptom distress, decrease medication use, and enhance quality of life.1–4 A recent systematic review indicated that acupuncture may constitute a nonpharmacologic means of pain relief for patients nearing the end of life and may also prove beneficial for the relief of dyspnea.5

Beginning in 1997, Kaiser Permanente Northwest (KPNW) Hospice began offering acupuncture services on a limited basis to hospice patients and their caregivers to complement current medical treatment by offering a method to ameliorate undesirable side effects from needed analgesic and sedative medications. This program, funded by donations, typically offers a series of five acupuncture treatments to those referred by hospice staff or to those requesting acupuncture treatment. On receipt of a referral, one of two program acupuncturists will visit the patient at home, assess the patient's condition, and deliver a treatment. Both acupuncturists have contracted with KP since the acupuncture project's inception, are licensed with the State of Oregon, and have completed master's-level training in acupuncture and Oriental medicine. We report here on the initial evaluation of this acupuncture program, through an analysis of both qualitative and quantitative data, assessing processes and outcomes associated with acupuncture treatment delivered to patients receiving home hospice services.

Editors Note.

This preliminary report is being published to complement the article in this issue “The Dartmouth Atlas Applied to Kaiser Permanente: Analysis of Variation in Care at the End of Life” in which the authors conclude: “Greater emphasis on palliative care approaches for patients with chronic conditions and earlier transition to the use of hospice would create a better match between the expressed desires of patients and the care they receive, thus improving member and family satisfaction as well as quality of care. In addition, earlier transition to hospice in KP could be one important tool for avoiding undesired and nonbeneficial ICU use, given the negative correlation between hospice and ICU use identified in this analysis.”

Methods

Interviews with Program Acupuncturists

In-person, audiotaped interviews were conducted with the two program acupuncturists to obtain subjective and descriptive information about the acupuncture program. The 90-minute interviews explored how they practiced with hospice patients and what they perceived as successful treatment outcomes, both expected and experienced. The acupuncturists were asked a series of open-ended questions designed to elicit information regarding provision of care to home hospice patients. Overarching questions/topics included the following:

How do you practice with patients?

Describe health and disease/illness, healing, or cure

Describe the outcomes of successful intervention.

The audiotaped interviews were transcribed verbatim, and content analysis6 was performed with the interview data to identify and code systematically the treatment-delivery processes and treatment outcomes described by practitioners. To ensure reliability, a second researcher read transcripts, coded interview passages, and discussed preliminary findings.

Retrospective Chart Review of Home Hospice Patients

The first author and one of the study acupuncturists audited electronic chart data representing the hospice patients enrolled in KPNW Hospice in 2003. The chart review focused on patient demographic and health characteristics, chief complaints, treatment modalities used, and treatment success, which were typically available for collection despite often incomplete charting. A relatively crude metric was used to determine degrees of treatment success: Outcomes were deemed fair, good, or excellent on the basis of whether these or similar words were used to describe progress. A judgment was also made regarding categorization on the basis of consistent progress noted versus progress noted only at one point; for example, if a superlative was used to describe progress on more than one occasion, outcomes were deemed excellent. (It should be noted that there was not a category for no outcome or poor outcomes: When a progress note was not made, it was unclear whether the omission was due to no treatment results or to no charting).

I think of healing as … giving them whatever kind of peace and whatever kind of relief I can bring them.

Results

Acupuncturist Interviews: Results from Narratives

1. Delivery of Acupuncture Treatment: Both practitioners described how the nature and condition of the patients, as well as the practical realities relating to the home setting, influenced their treatment procedure. These issues affected the treatment process, constituting a departure, to varying degrees, from the way they typically delivered therapy. For example, both acupuncturists discussed differences in how they assessed patients:

“I perform tongue [inspection] and pulse and palpation, but mostly as an introduction to the patient. I'm not getting a lot of information from that. I use that as a way of initially touching them. I do get information, but generally I already know that these people are gravely ill.”

Both acupuncturists also noted that their goals for healing were different in this patient population:

“Their tongues are black and they take many medications and they can't breathe and they hurt, and I'm not going to give them health—there is nothing I can do for that. I think of healing as … giving them whatever kind of peace and whatever kind of relief I can bring them.”

In terms of treatment delivery, features of the home setting both influenced how treatments were administered and provided additional assessment information:

“When I go into their home, the only piece of equipment I take, other than my bag full of needles and swabs and such, is a little folding stool that I whip out and sit on, move around if I need to. In some homes I need to use it as a little table because there is literally nowhere else to put things, because their things are piled everywhere—like in my dining room—only in their houses things are everywhere because they are dying and nobody is around who has energy to take care of the day-to-day things.”

“It's an amazing experience; so different from working privately, where you see only what the patient chooses to show you. When you go to their home, you see everything; you see how they live. You see the family dynamic.”

2. Intervention Outcomes Observed by Practitioners:

-

Symptom Control: Both practitioners noted that symptom control was a central goal and often a resultant outcome of treatment. For example:

“Anxiety usually responds pretty well, and so do nausea and different kinds of pain. Lung symptoms, like cough and shortness of breath, also respond pretty well.”

-

Psychosocial and Spiritual Outcomes: Practitioners also observed what they considered additional psychosocial and spiritual outcomes. Often these outcomes arose as a result of ameliorating or attenuating pain symptoms or other chief complaints. In other cases, these outcomes were perceived to arise directly from the treatment. For example:

“They get to that place where their spirit is at peace, and it may be only while the needles are in, or for an hour afterwards, but getting there is like meditating—you take that moment and what it gives you, whatever insight, whatever momentary relief.”

“Reduced pain is another part of the picture—the acupuncture treatments in many cases give people that little time when you see their face change and they relax.”

Retrospective Chart Review

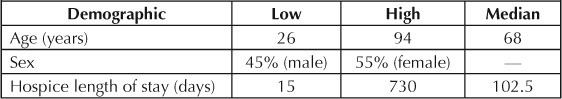

The median length of stay in hospice for this sample was 102.5 days. The median time from admission-to-hospice to acupuncture referral was 7 days (range, 0–147 days). Selected hospice patient characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of hospice patients (n = 71)

Acupuncture was the most-used treatment modality. Ear seeds, essential oils, and magnets, all within the scope of practice for acupuncturists, were also employed in limited cases. (Note: Ear acupuncture points may be stimulated for a longer period of time by using small seeds from the Vaccaria plant, which are held in place on the ear with a small piece of adhesive tape. To facilitate relaxation, calming essential oils, such as lavender, were occasionally employed as were magnets instead of needles on particular acupuncture points to facilitate energy flow.) Each treatment/acupuncture point prescription was tailored to the individual patient. The median number of treatments was three.

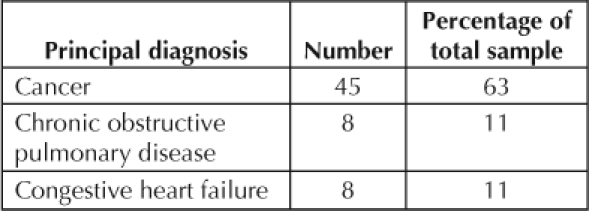

A cancer diagnosis was noted for 63% of the acupuncture program patients in 2003 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Diagnosis demographics

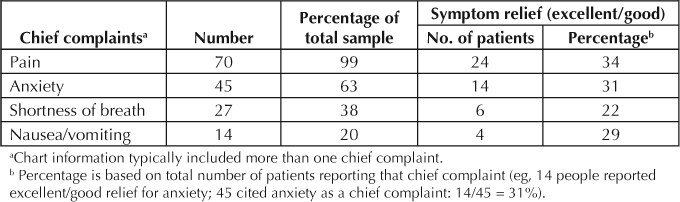

Only excellent or good results were noted (fair results not included) in the charts of 24 patients for pain (34%), 14 patients for anxiety (31%), 6 patients for shortness of breath (22%), and 4 patients for nausea/vomiting (29%). Other health and outcome data regarding acupuncture recipients are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Chief complaints and symptom relief

As a routine, at the beginning of each visit, the acupuncturists would ask the patient: “How are you doing? Did the acupuncture seem to help?” In their chart note of the patient's response, they would report any adverse events—such as significant bleeding, injury from a needle, etc. None was noted for any patient. One spot of rash at the site of a magnet was noted, but after that the practice was discontinued.

The home setting provided the practitioners with additional information pertaining to patients and their family life that they would not glean from an office visit.

Discussion

Acupuncturist Interviews

Two important issues emerged from the acupuncturist interviews. First, the acupuncturists noted that the nature and condition of both the patient and the realities of the home setting influenced their treatment procedure, which constituted a departure from the way they typically delivered therapy. The home setting provided the practitioners with additional information pertaining to patients and their family life that they would not glean from an office visit. The home visit, however, could involve limited space and chaotic conditions, often requiring practitioners to problem-solve regarding setting up their treatment space and positioning patients to treat them. The advanced nature of the disease process in hospice patients required the practitioners to modify healing goals and to deliver treatments focused on symptom control: “giving them whatever kind of peace and whatever kind of relief I can bring them.”

Second, the acupuncturists noted that symptom control was a central goal and a resultant outcome of treatment. However, they observed that additional psychologic, social, and spiritually oriented outcomes resulted from treatment, regardless of whether these outcomes were the principal goal of treatment. These observations echo those of four other hospice acupuncturists working throughout Oregon who were interviewed as part of an ongoing qualitative study (KK, ES, unpublished data, 2005).

Patient Chart Reviews

Information culled from review of the charts of 71 patients (representing the year 2003) revealed a median age of 68 years, a 55% female sample, and a principal diagnosis of cancer in 63% of cases. The most commonly cited chief complaints were pain (70%), anxiety (45%), shortness of breath (27%), and nausea/vomiting (14%). Positive results from acupuncture intervention were noted in many instances. Results suggest that acupuncture may assist hospice patients in control of symptoms often affecting this population and contributing to a diminished quality of life.

A recent study evaluating the experience of dying patients in both home and institutional settings reported that approximately one-quarter of patients did not receive adequate treatment for pain or dyspnea.7 Even when medications used in end-of-life care are effective in relieving or attenuating symptoms, they generally are not without side effects. Indeed, the Joint Commission (known until 2007 as the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations) standards emphasize the use of nonpharmacologic means of addressing symptom management for terminally ill patients.

In their interviews with patients after admission to palliative care units, Cohen et al8 reported that patients discussed improvements in quality of life beyond those relating to symptom control, including changes in physical, emotional, and interpersonal functioning; spiritual outlook; and preparation for death. The use of acupuncture as an adjunct to standard hospice care may prove beneficial to this group of health care recipients.

Conclusion

The hospice program acupuncturists described their practice with this group of patients as a departure from how they treat patients in a typical practice context, with a greater focus on providing comfort through ameliorating symptoms and a diminished focus on more holistic goals, which are typical elements of an acupuncture intervention. Nonetheless, the acupuncturists observed additional outcomes in psychological, social, and spiritual domains, regardless of whether these outcomes were the principal focus of treatment.

Results from this preliminary evaluation lend support to the assertion that acupuncture constitutes a promising and effective intervention to be employed in an integrative fashion in the palliative care/end-of-life context. Interview data align with outcomes that reflect the underlying philosophic orientation of hospice, acupuncture, and the models underlying current quality-of-life instruments for end of life.9–11 For example, the fundamental ideologies of each emphasize patient autonomy, treating the whole person, and healing or making one whole.

Chart data were incomplete, so we are now looking at additional, more comprehensively annotated charts. Taken together, these data comprise a preliminary expansion and clarification of the accumulating anecdotal reports that acupuncture is a promising adjunctive therapy for those nearing the end of life in the home-hospice setting. Likewise, systematic evaluation of programs like this will help to focus the design of future clinical studies in this important domain. For example, what are the best outcome instruments to use and endpoints to gauge in this population? Future preliminary studies will examine the expectations and experiences of both patients and their caregivers regarding the receipt of acupuncture while enrolled in hospice.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM grant number T32-AT001287 and T32-AT002688).

Katharine O'Moore-Klopf of KOK Edit provided editorial assistance.

References

- Burden B, Herron-Marx S, Clifford C. The increasing use of Reiki as a complementary therapy in specialist palliative care. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2005 May;11(5):248–53. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2005.11.5.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard RE. Music therapy in hospice and palliative care: a review of the empirical data. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2005 Jun;2(2):173–8. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng G. A year of acupuncture in palliative care. Palliat Med. 1999 Mar;13(2):163–4. doi: 10.1191/026921699676243035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie DJ, Kampbell J, Cutshall S, et al. Effects of massage on pain intensity, analgesics and quality of life in patients with cancer pain: a pilot study of a randomized clinical trial conducted within hospice care delivery. Hosp J. 2000;15(3):31–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan CX, Morrison S, Ness J, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine in the management of pain, dyspnea, and nausea and vomiting near the end of life: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000 Nov;20(25):374–87. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00190-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005 Nov;15(9):1277–88. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA. 2004 Jan 7;291(1):88–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SR, Boston P, Mount BM, et al. Changes in quality of life following admission to palliative care units. Palliat Med. 2001 Sep;15(5):363–71. doi: 10.1191/026921601680419401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings B. Individual rights and the human good in hospice. Hosp J. 1997;12(2):1–7. doi: 10.1080/0742-969x.1997.11882851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katpchuk T.The web that has no weaver: understanding Chinese medicine. New York: Congdon & Weed; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrell BR, Wisdom C, Wenzl C. Quality of life as an outcome variable in the management of cancer pain. Cancer. 1989 Jun 1;63(11 suppl):2321–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890601)63:11<2321::aid-cncr2820631142>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]