Introduction: What's the Problem?

Everyone is working hard, but the quality of chronic care is still mediocre. Donald Berwick, MD, says “every system is designed perfectly to achieve the results that it achieves.”1 The problem is the growing mismatch between the chronic care needs of the population and the acute care orientation of the health care system. Sixty-five million older people with multiple chronic conditions are trying to get health care from a system that is designed to treat acute illnesses and injuries. It's as though we are trying to put a square peg in a round hole. We will continue to get the poor results we are now getting until we redesign the system.

Guided Care is a new model for “chronic care” that is now being tested by Kaiser Permanente (KP) in the Baltimore-Washington, DC area. Guided Care is primary health care infused with the operative principles of recent innovations to ensure optimal outcomes for patients with chronic conditions and complex health care needs. A registered nurse who has completed a supplemental educational curriculum works in a practice with several primary care physicians, conducting eight clinical processes for 50–60 multimorbid patients.

A Typical Case

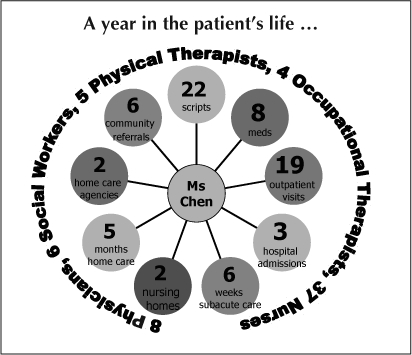

Ms Marian Chen is a 79-year-old widow who lives alone. She receives Social Security benefits and a modest pension; she is enrolled in a KP Medicare Health Plan. Her daughter lives ten miles away and is busy dealing with her three teenagers. Ms Chen has five chronic conditions for which she sees three physicians and takes eight prescription medications every day. The patient has had a very busy and medically complex year. She has seen eight physicians, five physical therapists, four occupational therapists, 37 nurses, and six social workers. This was the result of her chronic conditions flaring up and causing two hospitalizations, followed by inpatient postacute care and home care (Figure 1). At each transition, a new team of clinicians assessed the patient and created a new care plan.

Figure 1.

A year in the patient's life …

Despite her insurance coverage, the patient has incurred significant out-of-pocket costs, increasing her stress level. The patient rates her quality of life as poor. Her daughter, to help, has reduced her workload to half-time, and is now considering nursing home options for her mother. She doesn't think she can keep doing this much longer.

The family's experiences, which are not unusual, show that chronic care is:

fragmented

discontinuous

difficult to access

inefficient

unsafe

expensive.

The Nightmare of Navigation

Not surprisingly, the patient is often confused by the complex care she has been getting from multiple clinicians—and by all the medications that she is supposed to be taking. She is discovering that health care for people with chronic conditions “… is a nightmare to navigate.”2 We designed Guided Care to improve the quality of care and the quality of life for people like Ms Chen.

The Cost of Chronic Care

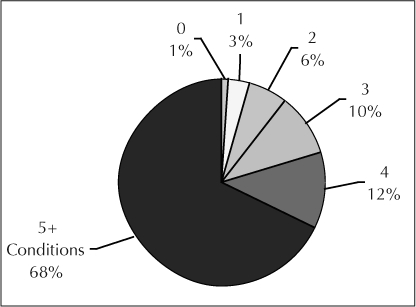

Figure 2 shows the nation's Medicare expenditures for beneficiaries with different numbers of chronic conditions. Patients having four or more chronic conditions (about 25% of the older population) account for 80% of all Medicare spending. So chronic care stresses not only the patient, the patient's family, and the employer, but also the budgets of health care organizations and the federal government. Today there are about 65 million older Americans with multiple chronic conditions; by 2010 there will be 70 million. Unless changes are made, the magnitude of the chronic care problem will grow every year for the next three decades.

Figure 2.

The 23% of older people who have >4 chronic conditions account for 80% of Medicare spending.

The Chronic Care Model

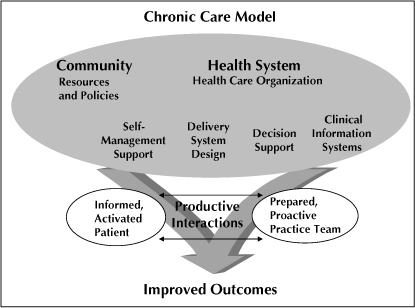

Wagner and Bodenheimer3 have proposed the “Chronic Care” model for improving chronic care (Figure 3). This model asserts that improving chronic care will require simultaneous improvements in support for self-management, design of practices, decision support, clinical information systems, and integration of community resources into health care. According to the model, improvements in these processes will foster more productive interactions between patients who are informed participants in their care, and practice teams that are prepared and proactive in providing care. Ultimately, these productive interactions should improve the outcomes of chronic care.

Figure 3.

The Chronic Care model for improving outcomes.

Sixty-five million older people with multiple chronic conditions are trying to get health care from a system that is designed to treat acute illnesses and injuries.

The Guided Care Model

In designing Guided Care, we used the Chronic Care model to select several successful innovations in chronic care. We then combined these innovations to create the Guided Care model.

During the past 20 years, pioneers have created innovations capable of improving several of the individual processes of chronic care. Kate Lorig, RN, DrPH, for example, has shown that her chronic disease self-management course can empower patients to become more informed and active in their own health care, resulting in improved quality of life and lower health care costs.4 Similarly, Mary Naylor, RN, PhD, and Eric Coleman, MD, MPH, have developed approaches to transitional care that can reduce the need for readmission to hospitals.5,6 Others have conducted successful experiments with family caregivers, disease management, and case management.

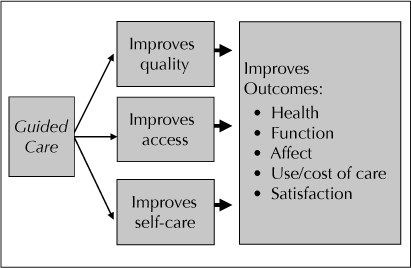

To create the Guided Care model, we combined the principles underlying such innovations and integrated them with primary care. We hypothesize that this approach improves the quality of care, patients' access to care, and their capacity for self care, thus resulting in improved health outcomes (Figure 4). Our goal is to develop a model of care that is sustainable and diffusible throughout the health care system. Therefore, we also designed Guided Care to be:

effective in practices throughout America

financially sustainable

attractive to physicians and nurses

valuable to health care organizations, and

popular with patients and caregivers.

Figure 4.

How Guided Care improves outcomes.

What Guided Care Looks Like in Practice

Guided Care is driven by a highly skilled registered nurse in a primary care office. The Guided Care nurse assists three to four physicians in providing high-quality chronic care for their patients in need of good chronic care.

Who is Eligible for Guided Care?

Those eligible for Guided Care are high-risk patients with several chronic conditions and complex health care needs in a primary care practice. To select eligible patients, we use predictive modeling software to analyze patients' encounter data for the previous year. This “hierarchical condition category” (HCC) softwarea assigns points to each diagnosis from each encounter and computes a risk rating for each patient. The 25% of patients with the highest risk of needing complex health care in the coming year are eligible to receive Guided Care.

Preparing the Guided Care Nurse

Curricular Phase

Critical to the success of Guided Care is the preparation of the Guided Care nurse. We have designed a case-based, three-week curriculum that teaches RNs the special skills they will need to practice Guided Care, including the use of the Guided Care electronic health record (EHR), transitional care, motivational interviewing, evidence-based guidelines for managing chronic conditions, health insurance coverage, and working with family caregivers and community agencies. The curriculum includes self-learning material and interactive workshops with instructors and other nurses.

Integrative Phase

Following the three-week curricular phase in the classroom, the nurse completes a four- to five-month integration into the primary care practice. To become an effective member of the practice, the nurse develops working relationships with the physicians, the other nurses, the support staff, and the receptionists, learning how each part of the practice functions. At the same time, the nurse acquaints each staff member with the role of the Guided Care nurse, while building a case-load of 50–60 patients.

Guided Care Services

For each patient, the Guided Care nurse provides eight services:7

1. Assessing

The nurse begins by performing a two-hour comprehensive assessment at the patient's home. This assessment covers medical conditions, medications, functional ability, mental status, exercise, nutrition, home safety, caregivers, other providers, and insurance. The nurse then reviews the patient's medical record and enters all the assessment data into the Guided Care EHR, which is separate from KP's “HealthConnect” electronic medical record.

2. Planning Care

On the basis of this assessment data and recent evidence-based guidelines, which are programmed into the EHR, the EHR generates the patient's individualized Care Guide. This Care Guide is an integrated compilation of all the recommendations for managing the patient's chronic conditions. The nurse and the primary care physician discuss and modify the Care Guide to meet the patient's unique circumstances. The nurse then discusses it with the patient and family, modifying it further to conform to their preferences and to obtain their “buy-in.” The final result is an evidence-based, realistic plan that addresses medications, diet, physical activity, self-monitoring, targets, and follow-up. The Care Guide is placed in the medical record and shared with other clinicians, as needed. On the basis of the Care Guide, the nurse then drafts a patient-friendly My Action Plan, which is owned by the patient and displayed in a plastic jacket on the refrigerator or other obvious visible place in the home. This two-page summary reminds the patient when to take medicines, what diet to follow, what exercise to do, when to monitor weight and blood pressure, what to watch out for, and when to see the doctor.

3. Monitoring

The nurse then begins the proactive monitoring phase of Guided Care. Rather than waiting for a problem to prompt the patient to access the health care system, the nurse reviews the Action Plan at least monthly with the patient. Most of these contacts are by telephone, but some are in person in the office, at the hospital, or in the home. If the patient doesn't call, the EHR reminds the nurse to call the patient or caregiver. The frequency of nurse's contacts with each patient fluctuates according to need.

4. Coaching

During the monitoring contacts, the nurse reviews the patient's self-management, point by point, making certain that all components of the plan are being followed. The nurse uses motivational interviewing techniques to help the patient overcome obstacles. The nurse confers with physicians as needed, making adjustments to the Action Plan and Care Guide.

5. Chronic Disease Self-Management

The Guided Care nurse refers most patients to a local “chronic disease self-management” (CDSM) course. The course consists of one two- to two-and-a-half-hour session per week for six weeks. At each session, a group of 10–15 patients meets with two trained, certified lay leaders, who lead a structured course that Stanford University has developed. The course aims to move people from passivity about their health care to a position of “mastery,” in which each person adopts an attitude of “I'm the master of my health; I'm primarily responsible.” Patients learn to set and attain health-related goals, interpret their own symptoms, and use the health care system appropriately.

6. Educating and Supporting Caregivers

Each Guided Care nurse leads a sequence of classes and support group sessions for 5–10 caregivers. The caregiver classes, which meet weekly for six weeks, provide general information on how to be a caregiver. Following this course, the nurse leads an ongoing monthly support group for caregivers and monitors their status quarterly by telephone.

7. Coordinating Transitions Between Providers and Sites of Care

To help coordinate complex care, the Guided Care nurse provides a brief but complete summary of the patient's health and health care (the Care Guide) to the patient's other providers, eg, hospitals, specialists, rehabilitation therapists, and home care nurses. One of the nurse's highest priorities is to smooth transitions between sites of care, especially into and out of hospitals. The nurse monitors the patient and family through the hospital stay and prepares them for discharge before they go home. When they do go home, the nurse visits them on the first day, making sure they have what they need and that they understand how to care for themselves, how to take medications, what to watch for, and that they have necessary contact information—emergency phone numbers and e-mail addresses—should problems or questions arise.

8. Access to Community Services

The Guided Care nurse also facilitates patients' access to many services provided by community agencies, such as Meals-on-Wheels, transportation services, senior centers, adult day health centers, and the Alzheimer Association.

Patients learn to set and attain health-related goals, interpret their own symptoms, and use the health care system appropriately.

Pilot Study

We conducted a pilot study for one year to assess the feasibility of providing Guided Care in a community primary care practice. We prepared one nurse, who then worked with two internists and their high-risk older patients in a practice in urban Baltimore, MD.

Surveys of the patients who received Guided Care and similar patients who received “usual care” in the practice showed that Guided Care recipients experienced more improvement in the quality of their care than did the usual care group.8 Insurance claims revealed that the costs of health care were lower for the Guided Care patients than for the usual care patients.9

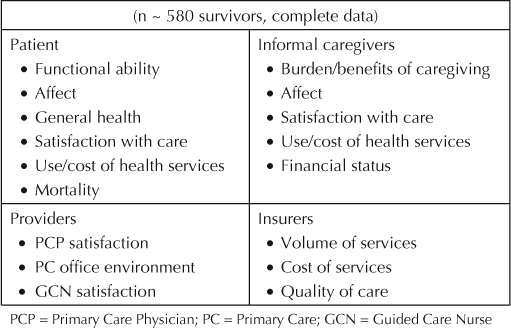

Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial

We are now conducting an eight-site cluster-randomized controlled trial of Guided Care involving more than 850 older high-risk patients, 320 family caregivers and 49 community-based primary care physicians. As shown in Table 1, we will compare several outcomes after 6 months and 18 months of Guided Care and usual care. The results of this study will determine the future of Guided Care. This randomized trial of Guided Care is supported by funds from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the National Institute on Aging, the John A Hartford Foundation, and the Jacob and Valeria Langeloth Foundation.

Table 1.

Outcome measurement at 18 months

(Paper presented at the Kaiser Permanente National Geriatric and Palliative Care Conference, November 3, 2006.)

Footnotes

a Public domain software available at: www.cms.hhs.gov/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/06_Risk_adjustment.asp#TopOfPage.

References

- Berwick DM. A primer on leading the improvement of systems. BMJ. 1996 Mar 9;312(7031):619–22. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7031.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine, Committee on Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academy Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T, Wagner EH, Grumbach K. Improving primary care for patients with chronic illness. JAMA. 2002 Oct 9;288(14):1775–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorig KR, Ritter P, Stewart AL, et al. Chronic disease self-management program: 2-year health status and health care utilization outcomes. Med Care. 2001 Nov;39(11):1217–23. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200111000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor MD, Brooten D, Campbell R, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up of hospitalized elders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 1999 Feb 17;281(7):613–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.7.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Sep 25;166(17):1822–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd CM, Boult C, Shadmi E, et al. Guided care for multi-morbid older adults. Gerontologist. 2007;47(5) doi: 10.1093/geront/47.5.697. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd C, Shadmi E, Conwell L, et al. The effect of Guided Care on quality of care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):S205. [Google Scholar]

- Sylvia ML, Griswold M, Dunbar L, et al. Guided care: cost and utilization outcomes in a pilot study. Dis Manag. 2007 doi: 10.1089/dis.2008.111723. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]