Acute gastrointestinal illness is common. An estimated 1.3 episodes per person occur each year in Canada, which translates to more than 40 million incidents at an estimated cost of $3.7 billion annually.1 Acute diarrhea is the second most common reason travellers returning from developing countries seek medical attention.2 In most instances, infectious diarrhea is self-limiting and treatment does not depend on identification of the responsible pathogen. The challenge for front-line clinicians is to recognize who requires testing and treatment.

The diagnostic yield of stool cultures is relatively low, estimated to range from 1.5% to 5.6%, which for example translates to a cost of US$952 to US$1200 per positive sample in the United States.3 Therefore, selective testing has been used to improve the cost-effectiveness of testing. When deciding whether testing is warranted, clinicians need to consider two questions: Will identification of the pathogen influence patient management, such as treatment or infection-control measures? Is identification of the causative agent important from a public health perspective? This primer is a summary of information obtained from recent reviews, clinical trials and guidelines.

What factors are important on history and examination?

Ingestion of many different bacteria, viruses, parasites and bacterial toxins can all lead to acute presentation of vomiting and diarrhea. Infectious diarrhea can be classified in several ways. One simple approach is to categorize patients into two groups: those who present with bloody diarrhea and those who present with nonbloody diarrhea (Table 1).3–5

Table 1:

| Agent | Nonbloody diarrhea | Bloody diarrhea |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterium |

|

|

| Virus |

|

|

| Parasite |

|

|

| Toxin |

|

The initial assessment of anyone presenting with infectious diarrhea should focus on severity, need for hydration and historical clues as to the cause in the patient. The decision to test for a specific pathogen, notify public health or start empirical treatment can be influenced by information acquired from thorough history-taking and physical examination.

Clinical features that help direct management include characteristics of the stool (e.g., bloody, watery), associated symptoms (e.g., fever, tenesmus) and, in some instances, the intensity of the vomiting. A detailed description of the clinical features associated with specific pathogens can be found in recent reviews.4–6

Additional information that may help in deciding whether testing is necessary and what testing is required includes underlying comorbidities, travel history, ingestion of unfiltered water, recent use of antibiotics, recent contact with a sick individual, dietary history focusing on foods that are at high risk for transmitting diarrheal illness (raw or undercooked meat, shellfish, eggs or milk), employment (daycare worker, food handler, health care worker) and residence in a closed facility (e.g., long-term care facility).3–5

Evidence of volume depletion is important to assess the severity of the illness. Reduced skin turgor and dry mucous membranes may reflect mild volume depletion. Tachycardia, an orthostatic drop in blood pressure, hypotension, changes in mental status, listlessness in children and weight loss in infants are all suggestive of severe dehydration.3 Examination of the abdomen may reveal focal or diffuse tenderness. Rebound tenderness suggestive of peritoneal inflammation should warrant further assessment to rule out severe colitis or perforation.

Who requires testing?

Because most instances of acute diarrhea are self-limiting and because the diagnostic yield of stool cultures is relatively low, testing everyone who presents with infectious diarrhea is not necessary.4 However, guidelines from the Infectious Disease Society of America suggest that stool cultures are important in certain settings because the identification of a pathogen can reduce unnecessary tests or treatments, allow for appropriate treatment where there is documented benefit and prevent inappropriate treatment that could be harmful.3 In addition, diagnostic testing is a critical part of ongoing surveillance, is essential to identify outbreaks, can provide public health officials with potential clues as to origin and can be useful when implementing public health measures, if appropriate (e.g., a Shigella infection in a person employed as a food handler).3

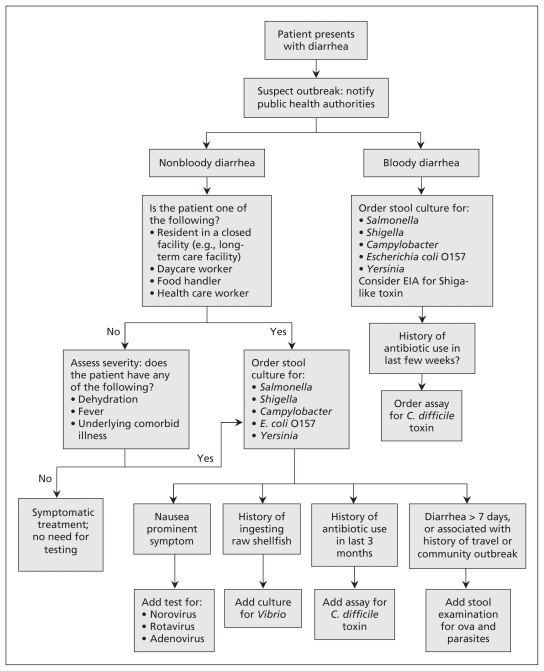

In general, testing should be considered when patients present with diarrhea of more than one day’s duration that is associated with bloody stools, fever, symptoms of sepsis or evidence of dehydration, recent antibiotic use or underlying immunocompromised state. Testing should also be considered when the diarrhea has important public health implications (e.g., the patient is employed as a food handler or daycare worker, or the investigation of clusters of a suspected outbreak is underway).3 Figure 1 outlines an approach to deciding who to test and what to test for.

Figure 1:

Algorithm for deciding when testing is required in patients who present with infectious diarrhea.3–5 Note: C. difficile = Clostridium difficile, EIA = enzyme immunoassay.

What treatment should be offered?

Treatment of infectious diarrhea can be divided into supportive treatment and pathogen-directed treatment.

Supportive treatment

The mainstay of treatment is oral hydration. The World Health Organization (WHO) has laid out clear guidelines regarding the composition of effective oral rehydration solutions.7 Commercial solutions are available for treating dehydration. When commercially available preparations are unavailable, homemade oral rehydration solutions can be prepared by mixing one teaspoon (5 mL) of salt and eight teaspoons (40 mL) of sugar in 1 L of water.8 Alternatively, a combination of water, fruit juices and salted crackers or soup may help replace fluids and electrolytes in patients with mild dehydration.4,9 In contrast, most sweat-replacement sports drinks do not meet the WHO standards, because they contain too many carbohydrates and do not have enough replacement electrolytes.10,11

Although many suggest a diet that contains easily digested foods such as bananas, rice, applesauce and toast (the BRAT diet), data from a pilot study show that dietary restriction does not enhance recovery.12 Over-the-counter medications such as bismuth subsalicylate (525 mg four times daily) and loperamide (4 mg initially, followed by 2 mg after each loose stool; maximum 16 mg/d) are available to treat acute diarrhea;13 however, an open-label comparison between these two medications published in 1990 found that loperamide was more effective.14 Loperamide is generally not recommended for use in patients with diarrhea associated with fever or bloody stools and should not be used in children less than three years old.13,15 Bismuth subsalicylate is not routinely recommended for use in children, because the salicylate component could predispose them to Reye syndrome.

Pathogen-directed treatment

There are many considerations in the decision to use antibiotics. Infectious diarrhea is a classic example of weighing the risks to the patient versus the benefits of the treatment.

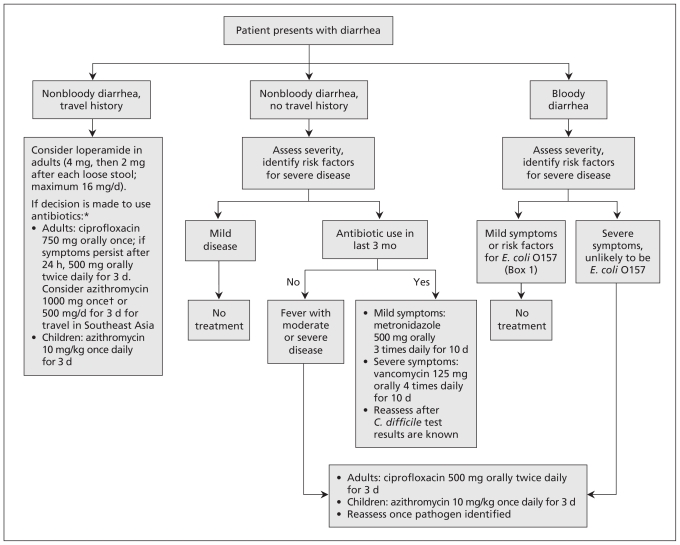

Because results of stool culture can take 48 hours, the treating physician needs to decide whether empirical treatment is required before confirming the diagnosis. When clinicians are considering the use of empirical therapy, it is helpful to categorize patients into the following groups: travellers with nonbloody diarrhea, non-travellers with nonbloody diarrhea and people with bloody diarrhea (Figure 2).3,5,13

Figure 2:

Algorithm for deciding whether empirical treatment of infectious diarrhea is required.3,5,12 *For nonbloody diarrhea with a history of travel, antibiotic use only reduces symptoms by 1–2 days and is associated with side effects; such treatment may not be justified in an era of antimicrobial resistance. †1000 mg of azithromycin can cause nausea. Note: C. difficile = Clostridium difficile, E. coli = Escherichia coli.

The most common causes of community-acquired, infectious diarrhea are viral and short-lived. Conservative management with hydration, with or without loperamide, is the most appropriate approach in most instances. Although guidelines suggest that antibiotic treatment can be considered for patients with fever and moderate or severe disease,3 the benefits need to be weighed against the potential disadvantages of antibiotic use. A meta-analysis of the combined data from six trials showed that diarrhea in patients with travel-associated, non-bloody diarrhea resolved one to two days earlier on average with antibiotic use; however, the incidence of side effects was greater among these patients than among those who were not given antibiotics.16 Despite these data, in an era of increasing rates of antimicrobial resistance, the small improvement in recovery from an otherwise self-limited illness may not justify the risk of antimicrobial resistance in the community. However, if symptoms are severe or worsen, empirical therapy can be considered (Figure 2).

Empirical treatment should be avoided in patients presenting with bloody stools, because potential causes include Escherichia coli O157 or other strains producing Shiga-like toxin. Although the data analyzed in a recent systemic review of antibiotic use and risk of hemolytic uremic syndrome in patients with a toxin-producing strain of E. coli O157 were conflicting, most clinicians recommend against antibiotic treatment.9,17,18 (Box 1 outlines the clinical features suggestive of infection with E. coli O157.19,20) In addition, Shigella infections are rarely life-threatening; thus, waiting for the results of the stool culture in a patient with bloody stools is reasonable before starting therapy.20

Box 1. Clinical features suggestive of infection with Escherichia coli O15719,20.

Bloody diarrhea preceded by one to three days of nonbloody diarrhea

Five stools in 24 hours

Abdominal tenderness

Worsening pain on defecation

No fever on presentation

No granulocytic reaction seen in differential count of leukocytes

In patients with a positive culture result, the decision to treat depends on the pathogen, the length of time from symptom onset, and comorbidities. Documented bacteremia requires antibiotic treatment. In Shigella and Campylobacter infections, antibiotic treatment is associated with reduced severity and bacterial shedding.4 However, in Campylobacter infections, a study published in 1982 showed that antibiotics must be given within four days after symptom onset,21 and a recent meta-analysis showed that antibiotic treatment shortened the duration of symptoms by only 1.3 days.22

Although treatment of Salmonella carries with it an increased risk of chronic carriage, bacteremia can occur in 2%–4% of patients.4 Therefore, treatment should be considered in individuals with a positive culture result and who are at risk of serious infection or complications of bacteremia (Box 2).3,5

Box 2. Risk factors where treatment of diarrhea associated with nontyphoidal Salmonella infection is indicated3,5.

Age < 6 months

Age > 65 years

Immunosuppression

Corticosteroid use

Inflammatory bowel disease

Prosthetic joint or vascular material

Hemoglobinopathy (e.g., sickle cell disease)

Hemodialysis

Patients with a positive test result for Clostridium difficile cytotoxicity should receive treatment with either metronidazole, if the infection is mild, or oral vancomycin, if the infection is severe.23 As mentioned previously, antibiotic treatment in patients with documented infection with E. coli O157:H7 or another strain producing Shiga-like toxin is not recommended because of the potential increased risk of hemolytic uremic syndrome.19

How can transmission be prevented?

Although infectious diarrhea is often associated with food-borne illness, many pathogens such as norovirus or Shigella can be readily transmitted person to person. Patients who have acute gastrointestinal illness should be reminded of the importance of hand hygiene as a way to prevent transmission to others. People at high risk of transmitting disease (e.g., those employed as food handlers, daycare workers or health care workers) should stay off work until symptoms resolve. However, even in healthy people, many pathogens, including norovirus, can shed for weeks following infection, which reinforces the need for attention to hand hygiene.24

Patients with underlying comorbidities, such as immunosuppression or chronic liver disease, are at increased risk of severe infections and should use safe food-preparation practices and avoid eating high-risk foods (e.g., raw shellfish and raw or undercooked meat). Contaminated swimming pools are well recognized as the source of infectious diarrhea in some outbreaks; therefore, patients with a Cryptosporidium infection should avoid swimming while symptomatic and for two weeks after the diarrhea stops, because of the potential for persistent shedding of oocytes.6

When should public health officials be notified?

Acute gastrointestinal illness is underreported to public health officials. Although laboratories are obligated to report isolates of many of the pathogens, the true incidence of disease is underrepresented. Recent data from the National Studies on Acute Gastrointestinal Illness suggest that, for every patient with verotoxigenic E. coli, Salmonella or Campylobacter infection detected by the national surveillance system in Canada, up to 49 people with such infections are missed in the community.1 In addition, the identification of clusters of parasitic infections can be important indicators of food- or water-borne outbreaks, such as the Cryptosporidium outbreak in North Battleford, Saskatchewan, in 2001.25

Because primary care physicians are often the first individuals to recognize clusters of cases, it is particularly important for them to report cases involving patients who would be at risk of transmitting infection or who may be indicators of potential outbreaks. This would include employees who are food handlers, day care workers, health care workers and residents in closed facilities. The reporting requirements may differ from province to province; clinicians should check with local public health officials regarding reporting obligations.

When should follow-up testing be done?

Although follow-up testing is not routinely recommended, there may be situations where confirmation is needed to show that a patient is no longer shedding the pathogen. Follow-up cultures may be recommended for food handlers or health care workers before they are allowed to return to work.1 Recommendations regarding which pathogens and patients should prompt follow-up testing can vary among provinces. As such, clinicians should consult their local public health officials for further guidance.

Key points

Acute infectious diarrhea is a common, usually self-limiting condition that is underreported to public health authorities.

Testing should be considered when patients present with diarrhea of more than one day’s duration associated with bloody stools, fever, symptoms of sepsis or evidence of dehydration, recent antibiotic use or underlying immunocompromised state, or when identification of the causative agent is important from a public health perspective.

Although antibiotics can reduce the duration of symptoms in nonbloody travellers’ diarrhea, use of antibiotics to treat this otherwise self-limited illness may not justify the risk of antimicrobial resistance in the community.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Both authors contributed equally to the writing and revision of the manuscript, and both approved the final version submitted for publication.

References

- 1.Thomas MK, Majowicz SE, Pollari F, et al. Burden of acute gastrointestinal illness in Canada, 1999–2007: interim summary of NSAGI activities. Can Commun Dis Rep 2008;34:8–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Freedman DO, Weld LH, Kozarsky PE, et al. GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Spectrum of disease and relation to place of exposure among ill returned travelers. N Engl J Med 2006;354: 119–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guerrant RL, Van Gilder T, Steiner TS, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the management of infectious diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis 2001;32:331–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thielman NM, Guerrant RL. Acute infectious diarrhea. N Engl J Med 2004;350:38–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DuPont HL. Clinical practice. Bacterial diarrhea. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1560–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies AP, Chalmers RM. Cryptosporidiosis. BMJ 2009;339: b4168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oral rehydration salts: production of the new ORS. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 2006. Available: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2006/WHO_FCH_CAH_06.1.pdf (accessed 2010 Dec. 15). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rehydration Project Oral rehydration solutions made at home. The Mother and Child Health and Education Trust; 2010. Available: http://rehydrate.org/solutions/homemade.htm (accessed 2009 Nov. 26).

- 9.Al-Abri SS, Beeching NJ, Nye FJ. Traveller’s diarrhoea. Lancet Infect Dis 2005;5:349–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atia AN, Buchman AL. Oral rehydration solutions in noncholera diarrhea: a review. Am J Gastroenterol 2009;104:2596–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris C, Wilkinson F, Mazza D, et al. Health for Kids Guideline Development Group. Evidence based guideline for the management of diarrhoea with or without vomiting in children. Aust Fam Physician 2008;37:22–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang DB, Awasthi M, Le BM, et al. The role of diet in the treatment of travelers’ diarrhea: a pilot study. Clin Infect Dis 2004;39:468–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hill DR, Ryan ET. Management of traveler’s diarrhoea. BMJ 2008;337:a1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DuPont HL, Flores Sanchez J, Ericsson CD, et al. Comparative efficacy of loperamide hydrochloride and bismuth subsalicylate in the management of acute diarrhea. Am J Med 1990;88:15S–9S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li ST, Grossman DC, Cummings P. Loperamide therapy for acute diarrhea in children: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2007;4:e98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Bruyn G, Hahn S, Borwick A. Antibiotic treatment for travellers’ diarrhea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;3:CD002242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Panos GZ, Betsi GI, Falagas ME. Systematic review: Are antibiotics detrimental or beneficial for the treatment of patients with Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection? Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006;24:731–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bavaro MF. Escherichia coli O157: What every internist and gastroenterologist should know. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2009; 11:301–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tarr PI, Gordon CA, Chandler WL. Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli and haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Lancet 2005;365:1073–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holtz LR, Neill MA, Tarr PI. Acute bloody diarrhea: a medical emergency for patients of all ages. Gastroenterology 2009;136: 1887–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anders BJ, Lauer BA, Paisley JW, et al. Double-blind placebo controlled trial of erythromycin for treatment of Campylobacter enteritis. Lancet 1982;1:131–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ternhag A, Asikainen T, Giesecke J, et al. A meta-analysis on the effects of antibiotic treatment on duration of symptoms caused by infection with Campylobacter species. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44:696–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerding DN, Muto CA, Owens RC., Jr Treatment of Clostridium difficile infection. Clin Infect Dis 2008;46:S32–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Atmar RL, Opekun AR, Gilger MA, et al. Norwalk virus shed-ding after experimental human infection. Emerg Infect Dis 2008; 14:1553–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stirling R, Aramini J, Ellis A, et al. Waterborne cryptosporidiosis outbreak, North Battleford, Saskatchewan, Spring 2001. Can Commun Dis Rep 2001;27:185–92 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]