Abstract

The high rate of comorbidity among mental disorders has driven a search for factors associated with the development of multiple types of psychopathology, referred to as transdiagnostic factors. Rumination is involved in the etiology and maintenance of major depression, and recent evidence implicates rumination in the development of anxiety. The extent to which rumination is a transdiagnostic factor that accounts for the co-occurrence of symptoms of depression and anxiety, however, has not previously been examined. We investigated whether rumination explained the concurrent and prospective associations between symptoms of depression and anxiety in two longitudinal studies: one of adolescents (N=1,065) and one of adults (N=1,317). Rumination was a full mediator of the concurrent association between symptoms of depression and anxiety in adolescents (z = 6.7, p < .001) and was a partial mediator of this association in adults (z = 5.6, p < .001). In prospective analyses in the adolescent sample, baseline depressive symptoms predicted increases in anxiety, and rumination fully mediated this association (z = 5.26, p < .001). In adults, baseline depression predicted increases in anxiety and baseline anxiety predicted increases in depression; rumination fully mediated both of these associations (z = 2.35, p = .019 and z = 5.10, p < .001, respectively). These findings highlight the importance of targeting rumination in transdiagnostic treatment approaches for emotional disorders.

Keywords: rumination, depression, anxiety, transdiagnostic, comorbidity

INTRODUCTION

The high degree of comorbidity between certain mental disorders, particularly depression and anxiety disorders (Brown, Cambell, Lehman, Grisham, & Mancill, 2001), has led to a search for mechanisms responsible for this comorbidity, often referred to as transdiagnostic factors (Ehring & Watkins, 2008; Harvey, Watkins, Mansell, & Shafran, 2004; Mansell, Harvey, Watkins, & Shafran, 2008; Norton, Hayes, & Springer, 2008). Many transdiagnostic factors have been proposed to link depression and anxiety, including elements of affect, attention, memory, reasoning, thought, and behavior (Ehring & Watkins, 2008; Harvey et al., 2004; Mansell et al., 2008; Moses & Barlow, 2006; Norton et al., 2008; Watson & Clark, 1984). Recently, repetitive negative thinking has been suggested to be an important transdiagnostic factor (Ehring & Watkins, 2008; Harvey et al., 2004; Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, 2008; Watkins, 2008). As Ehring and Watkins (2008) note, several disorder-specific definitions of maladaptive repetitive negative thinking exist, but all describe this process as (a) repetitive thoughts that are (b) passive and/or relatively uncontrolled, and (c) focused on negative content.

The specific type of repetitive negative thinking most frequently examined across a range of disorders, especially depression and anxiety disorders, is rumination, as defined by Nolen-Hoeksema (1991). She defines rumination as a pattern of responding to distress in which an individual passively and perseveratively thinks about his or her upsetting symptoms and the causes and consequences of those symptoms, while failing to initiate the active problem solving that might alter the cause of that distress (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991). Experimental studies show that inducing this type of rumination in the context of distress leads to increases in both depressed and anxious mood (Blagden & Craske, 1996; McLaughlin, Borkovec, & Sibrava, 2007). Studies using questionnaire measures of rumination such as the Ruminative Responses Scale (Treynor, Gonzalez, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2003) show that rumination predicts the later development of depressive symptoms (Broderick & Korteland, 2004; Nolen-Hoeksema, Morrow, & Fredrickson, 1993; Nolen-Hoeksema, Parker, & Larson, 1994; Nolen-Hoeksema, Stice, Wade, & Bohon, 2007; Schwartz & Koenig, 1996) as well as the future onset, number and duration of major depressive episodes (Just & Alloy, 1997; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2007; Robinson & Alloy, 2008). The tendency to ruminate also has been associated with self-reported symptoms of generalized anxiety (Fresco, Frankel, Mennin, Turk, & Heimberg, 2002; Harrington & Blankenship, 2002), post-traumatic stress (Clohessy & Ehlers, 1999; Mayou, Ehlers, & Bryant, 2002; Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991), and social anxiety (Mellings & Alden, 2000).

Rumination may lead to both anxiety and depression through a variety of mechanisms. Experimental induction of rumination in distressed individuals leads to more maladaptive, negative thinking (Lyubomirsky et al., 1998), less effective generation of solutions to problems (Donaldson & Lam, 2004; Lyubomirsky & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1995; Watkins & Baracaia, 2002; Watkins & Moulds, 2005), uncertainty and immobilization in the implementation of solutions to problems (Lyubomirsky, Kasri, Chang, & Chung, 2006; Ward, Lyubomirsky, Sousa, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2003), and less willingness to engage in distracting, mood-lifting activities (Lyubomirsky & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1993). Survey and observational studies also show that people who ruminate experience less social support and more social friction (Nolen-Hoeksema & Davis, 1999), and are viewed less favorably by others (Schwartz & McCombs, 1995).

Although multiple studies have examined the relationships between rumination and symptoms of anxiety and depression in the same sample (Fresco et al., 2002; McLaughlin et al., 2007; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000; Segerstrom, Tsao, Alden, & Craske, 2000), none of these studies has examined whether rumination accounts for the relationship between anxiety and depression in a sample. If rumination is indeed a transdiagnostic factor that leads to both depression and anxiety, we would expect that rumination is responsible, at least in part, for the comorbidity between symptoms of depression and anxiety and would account for their co-occurrence to a significant degree.

In the study reported here, we tested the prediction that rumination would statistically account for the relationship between symptoms of anxiety and depression both cross-sectionally and longitudinally. We tested this prediction in two samples, one comprised of early adolescents aged 11–14 years and the other comprised of adults ranging in age from 25–75 years. If rumination is truly a transdiagnostic factor in the co-occurrence of anxiety and depressive symptomatology, we expect to find evidence for its role in the overlap of such symptoms at a single point in time, across time, and in individuals at different points in the life course.

METHOD

Data for the current study were drawn from two separate longitudinal samples: a school sample of early adolescents and a community sample of adults. The adolescent sample description, measures, and procedure are described first, followed by those for the adult sample.

Adolescent Participants

The adolescent sample was recruited from the total enrollment of two middle schools (Grades 6–8) in central Connecticut that agreed to participate in the study, excluding students in self-contained special education classrooms and technical programs who did not attend school for the majority of the day. The schools were located in a small urban community (metropolitan population of 71,538). Schools were selected for the study based on demographic characteristics of the school district and their willingness to participate.

The parents of all eligible children (N = 1567) in the participating middle schools were asked to provide active consent for their children to participate in the study. Parents who did not return written consent forms to the school were contacted by telephone. Twenty-two percent of parents did not return consent forms and could not be reached to obtain consent, and 6% of parents declined to provide consent. Adolescent participations provided written assent. The overall participation rate in the study at baseline was 72%.

The baseline sample included 51.2% (N = 545) boys and 48.8% (N = 520) girls. Participants were evenly distributed across grade level. The race/ethnicity composition of the sample was as follows: 13.2% (N = 141) non-Hispanic White, 11.8% (N = 126) non-Hispanic Black, 56.9% (N = 610) Hispanic/Latino, 2.2% (N = 24) Asian/Pacific Islander, 0.2% (N = 2) Native American, 0.8% (N = 9) Middle Eastern, 9.3% (N = 100) Biracial/Multiracial and 4.2% (N = 45) Other racial/ethnic groups. Twenty-seven percent (N = 293) of participants reported living in single-parent households. The participating middle schools reside in a predominantly lower SES community, with a per capita income of $18,404 (Connecticut State Department of Education, 2005 based on data from 2001). School records indicated that 62.3% of students qualified for free or reduced lunch in the 2004–2005 school year. There were no differences across the two schools in demographic variables.

Two additional assessments took place after the baseline assessment. Of the participants who were present at baseline, 221 (20.8%) did not participate at the Time 2 assessment, and 217 (20.4%) did not participate at the Time 3 assessment, largely due to transient student enrollment in the district. Over the 4-year period from 2000–2004, 22.7% of students had left the school district (Connecticut Department of Education, 2006). Analyses were conducted using the sample of 1,065 participants who were present at the baseline assessment, excluding participants who were present at Time 2 and/or Time 3 but not at Time 1. Participants who completed the baseline but not both follow-up assessments were more likely to be female, χ2(1) = 6.85, p < 0.01, but did not differ in grade level, race/ethnicity, or being from a single parent household (p-values > 0.10). Participants who did not complete at least one of the follow-up assessments did not differ from participants who completed all three assessments on baseline depression or anxiety symptoms, or rumination (all p-values > 0.10).

Adolescent Measures

Depressive Symptoms

The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1992) is a widely used self-report measure of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. The CDI includes 27 items consisting of three statements (e.g., I am sad once in a while, I am sad many times, I am sad all the time) representing different levels of severity of a specific symptom of depression. The CDI has sound psychometric properties, including internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and discriminant validity (Kovacs, 1992; Reynolds, 1994). The item pertaining to suicidal ideation was removed from the measure at the request of school officials and the human subjects committee. The 26 remaining items were summed to create a total score ranging from 0 to 52. The CDI demonstrated good reliability in this sample (α = .82).

Anxiety Symptoms

The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC; March, Parker, Sullivan, Stallings, & Conners, 1997) is a 39-item widely used measure of anxiety in children. The MASC assesses physical symptoms of anxiety, harm avoidance, social anxiety, and separation anxiety and is appropriate for children ages 8 to 19. Each item presents a symptom of anxiety, and participants indicate how true each item is for them on a four-point Likert scale ranging from never true (0) to very true (3). A total score, ranging from 0 to 117, is generated by summing all items. The MASC has high internal consistency and test-retest reliability across 3-month intervals, and established convergent and divergent validity (Muris, Merckelbach, Ollendick, King, & Bogie, 2002). The MASC demonstrated good reliability in this sample (α = 0.88).

Rumination

The Children’s Response Styles Questionnaire (CRSQ; Abela, Brozina, & Haigh, 2002) is a 25-item scale that assesses the extent to which children respond to sad feelings with rumination, defined as self-focused thought concerning the causes and consequences of depressed mood, distraction, or problem-solving. The measure is modeled after the Response Styles Questionnaire (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991) that was developed for adults. For each item, youth are asked to rate how often they respond in that way when they feel sad on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from almost never (1) to almost always (4). The rumination subscale includes 13 items that are summed to generate a score ranging from 13 to 42. Sample items include: “Think about a recent situation wishing it had gone better” and “Think why can’t I handle things better?” The reliability and validity of the CRSQ have been demonstrated in samples of early adolescents (Abela et al., 2002). The CRSQ rumination scale demonstrated good reliability in this study (α = 0.86).

Adolescent Procedure

Participants completed study questionnaires during their homeroom period. All questionnaires used in the present analyses were administered at Time 1 and Time 3, and the rumination measure was additionally administered at Time 2. Four months elapsed between the Time 1 (November 2005) and Time 2 (March 2006) assessments, and three months elapsed between Time 2 and Time 3 (June 2006) assessments. This time frame was chosen to allow the maximum time between assessments to observe changes in internalizing symptoms while also ensuring that all assessments occurred within the same academic year to avoid high attrition. Given time constraints imposed by the school, we were only able to assess potential mediators at Time 2 whereas all study measures were administered at Times 1 and 3. Participants were assured of the confidentiality of their responses and the voluntary nature of their participation. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Yale University.

Adult Sample

The adult sample was comprised of adults living in the greater San Francisco Bay Area. Respondents were recruited using random-digit-dial telephone calls to adults living in San Francisco, San Jose, and Oakland, California. These specific communities were chosen to increase the racial/ethnic diversity of the sample. Telephone calls were made to residential numbers chosen randomly. When someone answered a call, they were asked whether anyone living in the household was between the ages of 25 and 35 years, 45 and 55 years, or 65 and 75 years. These age groups were selected to ensure that the sample include sufficient numbers of young, middle-aged, and older adults. If someone in the household met this age criteria, one person from the household was recruited for the study. Participants provided written informed consent.

Of the 1,789 individuals identified as eligible for participation, 1,317 completed a baseline interview (22.6% declined participation and 3.7% agreed to participate but did not return calls to schedule the interview). The baseline sample included 389 respondents aged 25–35 years (29.5%), 470 respondents aged 45–55 years (35.7%), and 262 respondents aged 65–75 years (19.9%). The racial/ethnic composition of the sample was as follows: 72% Non-Hispanic White, 9% Hispanic/Latino, 7% Black, 6% Asian/Pacific Islander, and 6% Multi-Racial or Other race/ethnicity. The majority of the sample (54%) was married or cohabiting, 18% were single, 16% were separated or divorced, 9% were widowed, and 3% were in a committed relationship but not cohabiting. The sample was diverse in regards to educational attainment, with 19% of respondents having a high school degree or less education, 27% with some college, 26% with a college degree, 8% with some post-graduate education, and 21% with a graduate or professional degree. The median income of the sample in 2004 was $40,000 to $50,000.

Of the 1,317 baseline respondents, 1,132 (85.9%) completed a second interview 1 year later. Respondents who did not complete a second interview had significantly higher interview-rated and self-reported depressive symptoms than respondents who completed both interviews (ps < .05). The analyses include only the 1,132 respondents who completed both interviews.

Adult Measures

Depression

Participants completed the 13-item form of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck & Beck, 1972), a self-report measure of current depressive symptoms. The BDI is one of the most widely used self-report instruments for detecting depressive symptoms. The BDI demonstrated good internal consistency in this sample (α = 0.82). Scores on the BDI ranged from 0 to 29 at baseline and from 0 to 26 at the follow-up interview. Interviewers also completed the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD; Hamilton, 1960) on each participant immediately after the interview. This scale provides an index of participants' current levels of depression. Information on the presence of specific symptoms came from participants' responses to the BDI. Interviewers also were instructed to use participants' nonverbal behaviors exhibited during the interview to make these ratings. Interviewers were extensively trained in the use of the HRSD. Scores on the HRSD have been shown to have good reliability and to correlate well with other clinical and self-report measures of depressive symptoms (Shaw, Vallis, & McCabe, 1985). In this study, the internal consistency of the HRSD was adequate (α = 0.74). Scores on the HRSD ranged from 0 to 36 at baseline and from 0 to 32 at the follow-up.

Anxiety

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck & Steer, 1990) was used to assess anxiety symptoms. The BAI has 21 items assessing the severity of anxiety symptoms using a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (severely; could barely stand it). Beck and Steer (1991) reported strong concurrent validity of the BAI with clinical ratings of anxiety. The BAI demonstrated good internal consistency in this sample (α = 0.88). Scores on the BAI ranged from 0 to 52 at baseline and from 0 to 41 at the follow-up.

Rumination

The Response Styles Questionnaire (RSQ; Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991) was administered to assess participants' tendencies to ruminate in response to dysphoric mood. The Ruminative Responses Scale of the RSQ includes 22 items describing responses that are self-focused (e.g., "I think, 'Why do I react this way?"), symptom focused (e.g., "I think about how hard it is to concentrate"), and focused on the possible consequences and causes of negative mood (e.g., "I think, 'I won't be able to do my job if I don't snap out of this' "). Respondents rate each item on a scale from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). The Ruminative Responses Scale demonstrated good internal consistency in this sample (α = 0.90). Scores on this scale ranged from 22 to 76 at baseline and from 22 to 75 at the follow-up. Previous studies have documented acceptable convergent and predictive validity of this scale (Butler & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1994; Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991).

Adult Procedure

Respondents were interviewed in person by an extensively trained clinical interviewer at both the baseline and follow-up interview, one year later. Most interviews were conducted in the respondent’s home. Interviews lasted approximately 90 minutes. Interviewers read aloud the instructions for each measure to the respondent and recorded their responses. Respondents were given a card with response options for all items that required the use of a Likert scale or involved a choice between groups of possible answers. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Stanford University.

Data Analytic Plan

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was used to perform all analyses using AMOS 6.0 software (Arbuckle, 2005). Analyses were conducted using the full information maximum likelihood estimation method, which estimates means and intercepts to handle missing data. Multiply indicated latent variables were created for depression, anxiety, and rumination using parcels of items from the relevant scales. Parcels were created using the domain representative approach, which accounts for the multidimensionality of these outcomes (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002), such that each parcel included items from each of the subscales of the relevant measures. In SEM, the use of parcels to model constructs as latent factors, as opposed to an observed variable representing a total scale score, confers a number of psychometric advantages including greater reliability, reduced of error variance, and increased efficiency (Kishton & Wadaman, 1994; Little et al., 2002).

After testing the measurement models for all constructs, separate mediation analyses were conducted to examine the role of rumination as a mediator of both the cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between depression and anxiety symptoms in each sample. Standard tests of statistical mediation were employed. In the cross-sectional analysis, we examined: 1) the association between depression and anxiety symptoms; 2) the association between depression and rumination; 3) the association between rumination and anxiety; and 4) the attenuation in the association between depression and anxiety after including rumination in the model.

In the longitudinal adolescent analysis, we examined: 1) the associations between Time 1 depressive symptoms and Time 3 anxiety symptoms (and vice versa); 2) the association between Time 1 symptoms and Time 2 rumination, controlling for Time 1 rumination; 3) the association between Time 2 rumination and Time 3 symptoms, controlling for Time 1 symptoms; and 4) the attenuation in the association between symptoms at Time 1 and Time 3 after accounting for changes in rumination from Time 1 to Time 2. This analysis provides a stringent test of mediation, which allowed us to investigate whether baseline symptomatology (e.g., depression) predicted changes in rumination and whether those changes predicted subsequent increases in symptoms (e.g., anxiety).

Because the adult sample included only two time points, we examined: 1) the association between Time 1 depressive symptoms and Time 2 anxiety symptoms (and vice versa); 2) the association between Time 1 symptoms and Time 2 rumination, controlling Time 1 rumination; 3) the association between Time 2 rumination and Time 2 symptoms, controlling for Time 1 symptoms and rumination; and 4) the attenuation in the association between symptoms at Time 1 and Time 2 after accounting for rumination at Time 1 and Time 2. The final mediation models were evaluated using the product of coefficients method. Sobel’s standard error approximation was used to test the significance of the intervening variable effect (Sobel, 1982). The product of coefficients approach is associated with low bias and Type 1 error rate, accurate standard errors, and adequate power to detect small effects (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002). Only adolescent participants who were present at baseline (N = 1,065) and adult participants who were present at both assessments (N = 1,132) were included in mediation analyses.

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 displays the mean and standard deviation of all measures at each time point. Table 2 provides the zero-order correlations among rumination and symptom measures in both samples. As expected, rumination was positively associated with depression and anxiety symptoms, which were positively associated with one another in both samples.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations of rumination and symptoms of anxiety and depression.

| Measure | Mean | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Adolescent Sample | ||

| Time 1 CRSQ Rumination | 10.94 | (7.65) |

| Time 1 CDI Depression | 9.67 | (6.44) |

| Time 1 MASC Anxiety | 40.19 | (15.39) |

| Time 2 CRSQ Rumination | 10.84 | (7.65) |

| Time 3 CRSQ Rumination | 10.18 | (8.07) |

| Time 3 CDI Depression | 10.63 | (8.15) |

| Time 3 MASC Anxiety | 34.80 | (18.05) |

| Adult Sample | ||

| Time 1 RSQ Rumination | 42.76 | (11.01) |

| Time 1 BDI Depression | 4.58 | (4.35) |

| Time 1 HRS-D Depression | 4.30 | (4.32) |

| Time 1 BAI Anxiety | 6.87 | (7.33) |

| Time 2 RSQ Rumination | 40.49 | (10.59) |

| Time 2 BDI Depression | 3.97 | (4.08) |

| Time 2 HRS-D Depression | 4.03 | (4.35) |

| Time 2 BAI Anxiety | 6.25 | (6.81) |

Note: CRSQ = Children’s Response Styles Questionnaire; Children’s Depression Inventory; MASC = Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; RSQ = Response Styles Questionnaire; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; HRS-D = Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory.

Table 2.

Correlations between rumination and symptoms of depression and anxiety.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent Sample | ||||||||

| 1. CRSQ Rumination T1 |

__ | |||||||

| 2. CDI Depression T1 |

.42** | __ | ||||||

| 3. MASC Anxiety T1 |

.55** | .28** | __ | |||||

| 4. CRSQ Rumination T2 |

.57** | .39** | .43** | __ | ||||

| 5. CRSQ Rumination T3 |

.48** | .35** | .41** | .61** | __ | |||

| 6. CDI Depression T3 |

.23** | .54** | .13** | .33** | .44** | __ | ||

| 7. MASC Anxiety T3 |

.35** | .24** | .53** | .44** | .69** | .33** | __ | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| Adult Sample | ||||||||

| 1. RSQ Rumination T1 |

__ | |||||||

| 2. BDI Depression T1 |

.50** | __ | ||||||

| 3. HRS-D Depression T1 |

.39** | .62** | __ | |||||

| 4. BAI Anxiety T1 |

.47** | .60** | .52** | __ | ||||

| 5. RSQ Rumination T2 |

.68** | .44** | .33** | .40** | __ | |||

| 6. BDI Depression T2 |

.37** | .60** | .42** | .47** | .50** | __ | ||

| 7. HRS-D Depression T2 |

.35** | .48** | .44** | .45** | .45** | .67** | __ | |

| 8. BAI Anxiety T2 |

.39** | .50** | .37** | .63** | .49** | .61** | .57** | __ |

Note: CRSQ = Children’s Response Styles Questionnaire; CDI = Children’s Depression Inventory; MASC = Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children; RSQ = Response Styles Questionnaire; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; HRS-D = Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory;

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01.

Measurement Models

The measurement models of adolescent internalizing symptoms and rumination were each constructed from four parcels of items created using the domain representative approach (Little et al., 2002), such that each parcel included items from each of the subscales of the relevant measures. All fit indices indicated that the measurement model of depression, χ2(2) = 1.83, p = .400, CFI = .99, and RMSEA = .01 (90% CI: .00–.05), anxiety, χ2(2) = 9.95, p = .007, CFI = .99, and RMSEA = .06 (90% CI: .02–.09), and rumination, χ2(2) = 4.23, p = .121, CFI = .99, and RMSEA = .03 (90% CI: .00–.07), fit the data very well.

The measurement models of adult internalizing symptoms and rumination were constructed using the same approach, with each model including four parcels of items. The model of adult depression was created from both the BDI and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. Fit indices indicated that this model fit the data adequately, χ2(2) = 18.37, p < .001, CFI = .99, and RMSEA = .08 (90% CI: .05–.11). The measurement models for adult anxiety symptoms, χ2(2) = 7.41, p = .025, CFI = .99, and RMSEA = .05 (90% CI: .01–.08), and rumination, χ2(2) = 26.14, p < .001, CFI = .99, and RMSEA = .09 (90% CI: .07–.12), also provided an adequate fit to the data.

Mediation Analyses

Cross-Sectional Analysis

We first examined rumination as a mediator of the cross-sectional association between symptoms of depression and anxiety. In the adolescent sample, depression was associated significantly with anxiety, β = .35, p < .001. Both depression, β = .51, p < .001, and anxiety symptoms, β = .64, p < .001, were associated significantly with rumination. In the final mediation model, depression was no longer associated with anxiety after rumination was added to the model, β = .04, p = .343. Sobel’s z-test revealed a significant mediating effect of rumination in the association between symptoms of depression and anxiety, z = 6.7, p < .001. All fit indices indicated that the model fit the data well: χ2(51) = 173.7, p < .001, CFI = .98, and RMSEA = .04 (90% CI: .04–.05).

In the adult sample, depressive symptoms were associated significantly with symptoms of anxiety, β = .71, p < .001. Symptoms of both depression, β = .56, p < .001, and anxiety, β = .51, p < .001, were associated significantly with rumination. In the final mediation model, a significant association remained between symptoms of depression and anxiety after rumination was added to the model, β = .61, p < .001. Sobel’s z-test revealed a significant mediating effect of rumination in the association between symptoms of depression and anxiety, z = 5.6, p < .001, suggesting that rumination was a partial mediator of the cross-sectional depression-anxiety association. All fit indices indicated that the model fit the data well: χ2(51) = 139.7, p < .001, CFI = .99, and RMSEA = .05 (90% CI: .04–.05).

Longitudinal Analysis

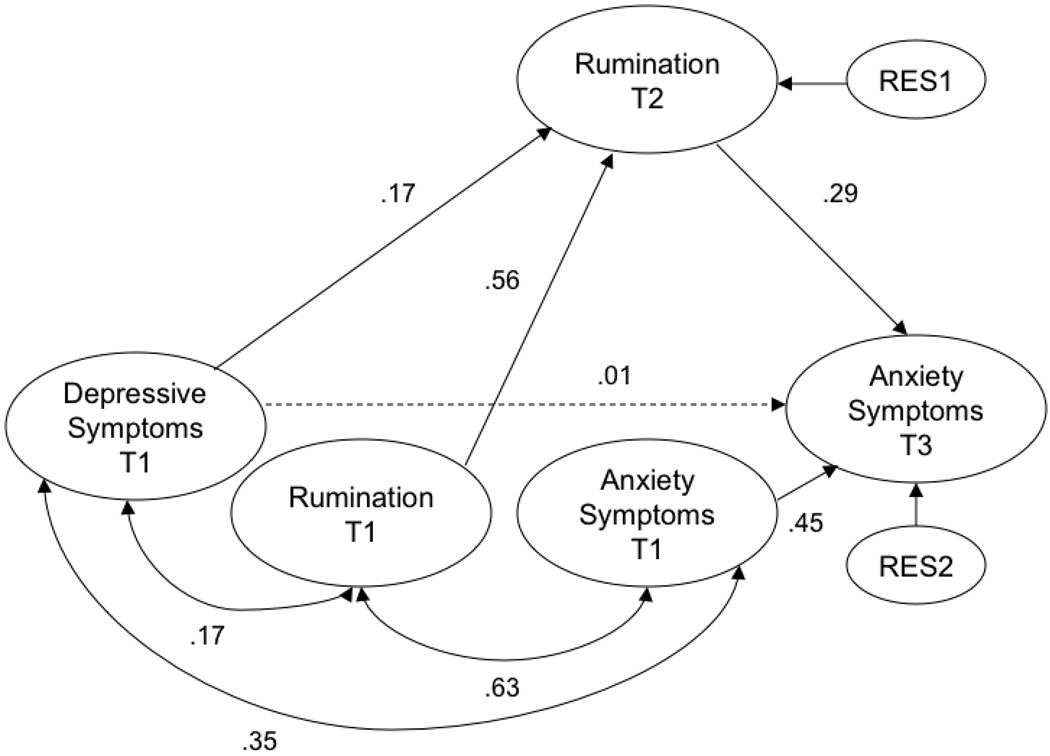

We examined two longitudinal mediation models in each sample. The first model examined the association between anxiety and subsequent increases in depressive symptoms, and the second model examined depression as a predictor of subsequent increases in anxiety symptoms. In the adolescent sample, Time 1 anxiety did not predict Time 2 depression, controlling for Time 1 depression, β = .02, p = .247. Time 1 depressive symptoms were associated significantly with Time 2 anxiety symptoms, controlling for Time 1 anxiety, β = .11, p < .01. We therefore examined rumination as a mediator of the longitudinal depression-Transdiagnostic Rumination 16 anxiety association. Time 1 depression was associated with Time 2 rumination, controlling for rumination at Time 1, β = .22, p < .001. Time 2 rumination was associated with Time 3 anxiety symptoms, controlling for Time 1 symptoms, β = .37, p < .001. In the final mediation model, Time 1 depression was no longer a significant predictor of Time 3 anxiety symptoms, controlling for Time 1 anxiety and Time 1 rumination, when Time 2 rumination was added to the model, β = .01, p = .927 (see Figure 1). The covariance between Time 1 symptoms of anxiety and depression and between Time 1 rumination and both anxiety and depression at Time 1 was accounted for in that final model. Sobel’s z-test revealed a significant indirect effect of Time 1 depression on Time 3 anxiety symptoms through rumination, z = 5.26, p < .001. Fit indices indicated that the model fit the data well: χ2(162) = 501.9, p < .001, CFI = .97, and RMSEA = .04 (90% CI: .04-.04). These findings indicate that depression at Time 1 predicted increases in rumination from Time 1 to Time 2 and that this increase in rumination, in turn, predicted increases in anxiety symptoms from Time 1 to Time 3.

Figure 1.

Note. Figure represents the longitudinal mediation model in adolescents. Numbers represent standardized path coefficients (β). All paths shown are significant (p < .05), except those drawn with broken lines. All constructs were modeled as latent variables. Due to space constraints, indicator variables are not displayed.

We next examined the longitudinal models in the adult sample. Time 1 anxiety was associated with Time 2 depression, controlling for Time 1 depression, β = .20, p < .001, and Time 1 depressive symptoms predicted Time 2 anxiety symptoms, controlling for Time 1 anxiety, β = .15, p < .001. We first examined the role of rumination in explaining the longitudinal association between anxiety and subsequent depression. Anxiety symptoms at Time 1 predicted rumination at Time 2, controlling for Time 1 rumination, β = .16, p < .001. Rumination at Time 2 is associated with Time 2 depressive symptoms, controlling for depression and rumination at Time 1, β = .43, p < .001. In the final mediation model, Time 1 anxiety was no longer a significant predictor of Time 2 depressive symptoms, controlling for Time 1 depression and rumination, when Time 2 rumination was added to the model, β = .06, p = .153; the covariance between Time 1 symptoms of anxiety and depression and between Time 1 rumination and both anxiety and depression at Time 1 also was modeled. Sobel’s z-test revealed a significant indirect effect of Time 1 anxiety symptoms on Time 3 depression through rumination, z = 5.10, p < .001. Fit indices indicated that the model fit the data well: χ2(162) = 1015.1, p < .001, CFI = .95, and RMSEA = .06 (90% CI: .06–.07).

Finally, we examined the extent to which rumination mediated the association between depressive symptoms and subsequent anxiety. Depressive symptoms at Time 1 predicted rumination at Time 2, controlling for Time 1 rumination, β = .20, p < .001. Rumination at Time 2 is associated significantly with Time 2 anxiety symptoms, controlling for anxiety and rumination at Time 1, β = .36, p < .001. In the final mediation model, Time 1 depression was no longer a significant predictor of Time 2 anxiety symptoms, controlling for Time 1 anxiety and rumination, when Time 2 rumination was added to the model, β = .10, p = .104; the covariance between Time 1 symptoms of anxiety and depression and between Time 1 rumination and both anxiety and depression at Time 1 also was modeled. Sobel’s z-test revealed a significant indirect effect of depression on anxiety symptoms through rumination, z = 2.35, p = .019. Fit indices indicated that the model fit the data well: χ2(162) = 949.9, p < .001, CFI = .96, and RMSEA = .06 (90% CI: .06-.06).

DISCUSSION

Increased interest in understanding the causes of disorder comorbidity has stimulated a search for transdiagnostic factors that play a role in the etiology and co-occurrence of multiple types of psychopathology. The identification of such factors has relevance both for improving theoretical models of disorder etiology and guiding clinical intervention. The current study evaluated rumination as a transdiagnostic factor by determining whether rumination explained the cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between symptoms of depression and anxiety. We examined whether rumination explained the co-occurrence of such symptoms in two large, prospective samples including both adolescent and adult participants. Our findings indicated that rumination accounts for a significant proportion of the overlap between depression and anxiety in both adolescents and adults, suggesting that rumination is indeed a transdiagnostic factor in the emotional disorders. Notable developmental differences were observed in the extent to which rumination accounted for the overlap in depression and anxiety, pointing to the importance of considering transdiagnostic factors within a developmental psychopathology framework.

One explanation of psychiatric comorbidity is that multiple disorders share etiologic factors (Angold, Costello, & Erkanli, 1999; Barlow, 2002). Watkins (2008) and others (Ehring & Watkins, 2008) have argued that rumination is one such transdiagnostic factor underlying both the mood and anxiety disorders. To date, however, little empirical research has investigated this claim directly. We addressed this gap in the literature, first, by examining the extent to which rumination accounted for co-occurring symptoms of depression and anxiety in adolescents and adults. Rumination completed mediated the cross-sectional association between symptoms of depression and anxiety among adolescents and was a partial mediator in adults. These findings provide support for rumination as a transdiagnostic factor underlying concurrent symptoms of depression and anxiety across two distinct developmental stages.

Rumination may have played a greater mediating role in the co-occurrence of depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents as compared to adults because internalizing psychopathology in youths is less differentiated. Numerous investigations of the structure of youth psychopathology have found that depression and anxiety load onto a unitary underlying dimension (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1979; De Clercq, De Fruyt, Van Leeuwen, & Mervielde, 2006; Wadsworth, Hudziak, Heath, & Achenbach, 2001), whereas they have typically differentiated into multiple factors in similar studies of adults (Krueger, 1999; Krueger & Markon, 2006; Watson, 2005). This pattern indirectly suggests that the core etiologic factors involved in the development of depression and anxiety in youths are highly overlapping. Our findings indicate that rumination is one such core factor underlying depression, anxiety, and their co-occurrence in adolescents. Another explanation for these developmental differences is that rumination may play a greater role in the development of anxiety in adolescents than in adults. Indeed, rumination was more strongly associated with anxiety than with depression both cross-sectionally and prospectively in our adolescent sample. It is important to note that rumination also explained a significant proportion of the concurrent overlap in depression and anxiety in adults, albeit to a lesser extent, suggesting the presence of additional factors driving the differentiation of negative affect into specific types of symptoms in adults.

The cross-sectional findings suggest that rumination plays an important role in explaining concurrent symptoms of depression and anxiety, but provide no information about whether rumination is involved in the temporal progression from depression to anxiety or from anxiety to depression. This issue was addressed in the longitudinal analyses. The results of these analyses confirm the cross-sectional findings, providing the most compelling evidence that rumination is an important transdiagnostic factor underlying mood and anxiety pathology. Among adolescents, rumination fully mediated the longitudinal association between depressive symptoms and later anxiety. Importantly, we conducted a stringent test of mediation using three time points. This analysis showed that depressive symptoms predicted increases in rumination over time and that these increases in rumination, in turn, accounted for the development of anxiety symptoms. Our finding that adolescent depressive symptoms predicted subsequent increases in anxiety symptoms is consistent with prior evidence from epidemiological and community samples (Costello, Mustillo, Erkanli, Keeler, & Angold, 2003; Pine, Cohen, Gurley, Brook, & Ma, 1998), and the mediation results suggest that the elevated risk for the development of anxiety among adolescents with depressive symptoms is attributable to rumination. We did not examine rumination as a mediator in the association between anxiety and later depression because anxiety symptoms at baseline did not predict increases in depressive symptoms in our adolescent sample. This result contrasts with findings from a large number of prospective studies documenting elevated risk for depression among adolescents with anxiety symptoms and disorders (Cole, Peeke, Martin, Truglio, & Seroczynski, 1998; Costello et al., 2003; Merikangas et al., 2003; Pine et al., 1998) and defies easy explanation. One possibility is that our adolescent sample was comprised predominantly of economically disadvantaged adolescents and included a considerably higher proportion of racial/ethnic minorities than these previous studies. High levels of depressive symptoms were already evident in the sample at baseline, suggesting that the onset of depressive symptoms may have occurred earlier in this relatively disadvantaged group of adolescents.

Among adults, rumination was a significant mediator in the prospective associations of anxiety symptoms with subsequent depression and of depressive symptoms with subsequent anxiety. Abundant evidence has documented strong temporal relationships between symptoms of anxiety and depression and high levels of successive comorbidity between major depression and anxiety disorders (Merikangas et al., 2003; Moffit et al., 2007; Pine et al., 1998). Our findings highlight the explanatory role of rumination in these reciprocal relations between symptoms of depression and anxiety over time. In particular, they suggest that ruminative responses to negative affect are associated with elevated risk for the development of comorbid symptoms of emotional disorders over time. These associations may result from the direct effects of rumination on positive and negative affect (McLaughlin et al., 2007) or from the wide range of other negative consequences of rumination including poor problem-solving and decreased interpersonal functioning (Lyubomirsky & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1995; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1994; Watkins & Baracaia, 2002; Watkins & Moulds, 2005).

The search for transdiagnostic factors has been fueled by a desire to develop “broad-spectrum” or “unified” treatments that target the common elements of multiple disorders simultaneously and do not require modification to address specific types of symptoms (Barlow, Allen, & Choate, 2004; Erickson, Janeck, & Tallman, 2007; McEvoy, Nathan, & Norton, 2009; Norton et al., 2008). Because comorbidity of emotional disorders is the rule as opposed to the exception (Kessler, Chiu, Demler, & Walters, 2005), particularly in clinical settings (Brown et al., 2001), treatments that target risk and maintenance factors that cut across diagnostic boundaries confer a number of practical and clinical advantages over therapies designed to treat specific disorders including greater efficiency, endurance of treatment effects, prevention of the recurrence of comorbid disorders following treatment of an index disorder, and ease of disseminating effective treatments (Addis, Wade, & Hatgis, 1999; Barlow et al., 2004; Brown, Antony, & Barlow, 1995; McEvoy et al., 2009). Our findings suggest that unified interventions for the emotional disorders should target rumination specifically. Although rumination has long been understood as an important factor in the etiology and maintenance of mood disorders (Just & Alloy, 1997; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1993; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1994; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008) and, increasingly, of anxiety pathology (Blagden & Craske, 1996; Mellings & Alden, 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000), traditional cognitive-behavioral therapies have not targeted rumination specifically. This is surprising given the robust prospective associations between rumination and the onset and maintenance of emotional disorders. However, a recent treatment specifically designed to reduce ruminative self-focus led to significant reductions in depression and associated comorbidity among adults (Watkins et al., 2007). This treatment utilized traditional cognitive-behavioral techniques, including functional analysis, to identify and reduce engagement in rumination and to help individuals adopt thinking styles that promote problem solving and adaptive processing of emotional experiences (Watkins et al. 2007). A recent study administered this treatment to a sample of adolescents with chronic PTSD; although no control group was included in the study, the treatment was associated with significant reductions in PTSD symptoms (Sezibera, Van Broeck, & Philippot, 2009). Although more rigorous empirical evaluation of this treatment is warranted, it represents a promising approach for addressing rumination directly in therapy. Incorporating techniques that specifically target rumination into unified treatment protocols for the emotional disorders stands to improve the efficacy of these interventions and represents an important goal for future clinical research.

Study findings should be interpreted in light of the following limitations. First, we examined self-reported symptoms of depression and anxiety rather than DSM-IV diagnoses based on a structured clinical interview. Our results therefore speak only to the role of rumination in co-occurring symptoms of depression and anxiety, not to the actual comorbidity of mood and anxiety disorders. Although it seems likely that rumination plays a similar role in explaining comorbid emotional disorders, this assertion requires empirical evaluation in future research. Second, we focused exclusively on symptoms of depression and anxiety and did not examine other co-occurring symptomatology. Rumination has been shown to predict disordered eating behaviors and substance abuse (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2007), both of which are frequently comorbid with emotional disorders (Blinder, Cumella, & Sanathara, 2006; Grant et al., 2004; Stice, Burton, & Shaw, 2004). It is therefore possible that rumination plays a role in the co-occurrence of these types of psychopathology with mood and anxiety disorders, a possibility that warrants investigation in future research. Third, there were differences in the measures used in the adolescent and adult samples, as well as differences in the demographic profiles of the two groups, that might have contributed to the differences in the pattern of results across samples. Replication of the apparent developmental trends in our analyses using differently-aged samples that are more demographically similar and that utilize the same measures of rumination, depression, and anxiety, will be important. On the other hand, our finding that rumination mediated the relationship between depression and anxiety in two samples using different measures of the primary constructs strengthens our conclusion that rumination is a significant mediator of the relationship between depressive and anxiety symptoms. Finally, despite our use of a prospective design, we cannot conclude that the associations between rumination and depression and anxiety symptoms observed here are causal. However, rumination has been shown experimentally to generate both depressed and anxious affect (Blagden & Craske, 1996; McLaughlin et al., 2007), increasing confidence that our results reflect true associations.

The current study identified rumination as a transdiagnostic factor responsible for the co-occurrence of symptoms of depression and anxiety in both adolescents and adults. Rumination accounted for a significant proportion of the concurrent overlap in symptoms of depression and anxiety, albeit to a greater degree among adolescents than adults. Rumination also explained the prospective relations between depression and anxiety indicating that rumination is responsible, at least in part, for the transitions over time between symptoms of depression and anxiety. These results point to the importance of incorporating intervention techniques targeting rumination into transdiagnostic treatment approaches for emotional disorders.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abela JR, Brozina K, Haigh EP. An examination of the response styles theory of depression in third- and seventh-grade children: a short-term longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:515–527. doi: 10.1023/a:1019873015594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock CS. The Child Behavior Profile: II. Boys aged 12–16 and girls aged 6–11 and 12–16. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1979;47:223–233. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addis ME, Wade WA, Hatgis C. Barriers to dissemination of evidence-based practices: Addressing practitioners' concerns about manual-based psychotherapies. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1999;6:430–441. [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40:57–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. AMOS 6.0 User's Guide. Chicago: SPSS, Inc.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH. Anxiety and its disorders. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Allen LB, Choate ML. Toward a unified treatment for emotional disorders. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35:205–230. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Beck RW. Screening depressed patients in family practice: A rapid technique. Postgraduate Medicine. 1972;52:81–85. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1972.11713319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the revised Beck Anxiety Inventory. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Blagden JC, Craske MG. Effects of active and passive rumination and distraction: A pilot replication with anxious mood. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1996;10:243–252. [Google Scholar]

- Blinder BJ, Cumella EJ, Sanathara VA. Psychiatric comorbidities of female inpatients with eating disorders. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2006;68:454–462. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000221254.77675.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick PC, Korteland C. A prospective study of rumination and depression in early adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;9:383–394. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Antony MM, Barlow DH. Diagnostic comorbidity in panic disorder: Effect on treatment outcome and course of comorbid diagnoses following treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:408–418. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Cambell LA, Lehman CL, Grisham JR, Mancill RB. Current and lifetime comorbidity of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders in a large clinical sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:585–599. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.4.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler ID, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Gender differences in response to depression mood in a college sample. Sex Roles. 1994;30:331–346. [Google Scholar]

- Clohessy S, Ehlers A. PTSD symptoms, responses to intrusive memories, and coping in ambulance service workers. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1999;38:251–265. doi: 10.1348/014466599162836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Peeke LG, Martin JM, Truglio R, Seroczynski AD. A longitudinal look at the relation between depression and anxiety in children and adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:451–460. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connecticut Department of Education. Strategic School Profile 2005–2006: New Britain Public Schools. Hartford, CT: Connecticut Department of Education; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Clercq B, De Fruyt F, Van Leeuwen K, Mervielde I. The structure of maladaptive personality traits in childhood: A step toward an integrative developmental perspective for DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:639–657. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson C, Lam D. Rumination, mood and social problem solving in major depression. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34:1309–1318. doi: 10.1017/s0033291704001904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehring T, Watkins E. Repetitive negative thinking as a transdiagnostic process. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2008;1:192–205. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson DH, Janeck AS, Tallman K. A cognitive-behavioral group for patients with various anxiety disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:1205–1211. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.9.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fresco DM, Frankel AN, Mennin DS, Turk CL, Heimberg RG. Distinct and overlapping features of rumination and worry: The relationship of cognitive production to negative affective states. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2002;26:179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, & Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–61. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington JA, Blankenship V. Ruminative thoughts and their relation to depression and anxiety. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2002;32:465–485. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AG, Watkins E, Mansell W, Shafran R. Cognitive behavioural processes across psychological disorders. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Just N, Alloy LB. The response styles theory of depression: Tests and an extension of the theory. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:221–229. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishton JM, Wadaman KF. Unidimensional versus domain representative parceling of questionnaire items: An empirical example. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1994;54:757–765. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children's Depression Inventory manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF. The structure of common mental disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:921–926. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.10.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Markon KE. Reinterpreting comorbidity: A model-based approach to understanding and clarifying psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2006;2:111–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.2.022305.095213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Cunningham WA, Shahar G, Widaman KF. To parcel or not to parcel: Examining the question, weighing the evidence. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:151–173. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Kasri F, Chang O, Chung I. Ruminative response styles and delay of seeking diagnosis for breast cancer symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2006;25:276–304. [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Self-perpetuating properties of dysphoric rumination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65:339–349. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Effects of self-focused rumination on negative thinking and interpersonal problem solving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:176–190. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansell W, Harvey AG, Watkins E, Shafran R. Cognitive behavioral processes across psychological disorders: A review of the utility and validity of the transdiagnostic approach. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2008;1:181–191. [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Parker JDA, Sullivan K, Stallings P, Conners CK. The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): Factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:554–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayou RA, Ehlers A, Bryant B. Posttraumatic stress disorder after motor vehicle accidents: 3-year follow-up of a prospective longitudinal study. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2002;40:665–675. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy PM, Nathan P, Norton PJ. Efficacy of transdiagnostic treatments: A review of published outcome studies and future research directions. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly. 2009;23:20–33. [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Borkovec TD, Sibrava NJ. The effect of worry and rumination on affect states and cognitive activity. Behavior Therapy. 2007;38:23–38. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellings T, Alden LE. Cognitive processes in social anxiety: The effects of self-focus, rumination and anticipatory processing. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000;38:243–257. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Zhang H, Avenevoli S, Acharyya S, Meuenschwander M, Angst J. Longitudinal trajectories of depression and anxiety in a prospective community study: The Zurich Cohort Study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:993–1000. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffit TE, Harrington H, Caspi A, Kim-Cohen J, Goldberg DA, Gregory AM, et al. Depression and generalized anxiety disorder: Cumulative and sequential comorbidity in a birth cohort followed prospectively to age 32 years. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:651–660. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.6.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses EB, Barlow DH. A new unified approach for emotional disorders based on emotion science. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15:146–150. [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Merckelbach H, Ollendick T, King N, Bogie N. Three traditional and three new childhood anxiety questionnaires: their reliability and validity in a normal adolescent sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2002;40:753–772. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:504–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Davis CG. "Thanks for sharing that": Ruminators and their social support networks. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:801–814. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.4.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J. A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: The 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1991;61:115–121. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J, Fredrickson BL. Response styles and the duration of episodes of depressed mood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:20–28. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Parker LE, Larson J. Ruminative coping with depressed mood following loss. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:92–104. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Stice E, Wade E, Bohon C. Reciprocal relations between rumination and bulimic, substance abuse, and depressive symptoms in female adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116(1):198–207. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008;3:400–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton PJ, Hayes SA, Springer JR. Transdiagnostic cognitive-behavioral group therapy for anxiety: Outcome and process. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2008;1:266–279. [Google Scholar]

- Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, Ma Y. The risk for early adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:56–64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM. Assessment of depression in children and adolescents by self-report measures. In: Reynolds WM, Johnston HF, editors. Handbook of depression in children and adolescents. New York: Plenum Press; 1994. pp. 209–234. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MS, Alloy LB. Negative cognitive styles and stress-reactive rumination interact to predict depression: A prospective study. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2008;27:275–291. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz JAJ, Koenig LJ. Response styles and negative affect among adolescents. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1996;20:13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz JL, McCombs TA. Perceptions of coping responses exhibited in depressed males and females. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality. 1995;10:849–860. [Google Scholar]

- Segerstrom SC, Tsao JCI, Alden LE, Craske MG. Worry and rumination: Repetitive thought as a concomitant and predictor of negative mood. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2000;24:671–688. [Google Scholar]

- Sezibera V, Van Broeck N, Philippot P. Intervening on persistent posttraumatic stress disorder: Rumination-focused cognitive and behavioral therapy in a population of young survivors of the 1994 genocide in Rwanda. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly. 2009;23:107–113. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw BF, Vallis TM, McCabe SB. The assessment of the severity and symptom patterns in depression. In: Beckham EE, Leber WR, editors. Handbook of depression: Treatment, assessment, and research. Homewood, IL: Dorsey Press; 1985. pp. 372–407. [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation model. In: Leinhart S, editor. Sociological Methodology. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Burton EM, Shaw H. Prospective relations between bulimic pathology, depression, and substance abuse: Unpacking comorbidity in adolescent girls. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;72:62–71. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treynor W, Gonzalez R, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27:247–259. [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth ME, Hudziak JJ, Heath AC, Achenbach TM. Latent class analysis of Child Behavior Checklist Anxiety/Depression in children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:106–114. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200101000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward A, Lyubomirsky S, Sousa L, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Can't quite commit: Rumination and uncertainty. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2003;29:96–107. doi: 10.1177/0146167202238375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins E, Baracaia S. Rumination and social problem solving in depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2002;40:1179–1189. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins E, Moulds M. Distinct modes of ruminative self-focus: Impact of abstract versus concrete rumination on problem solving in depression. Emotion. 2005;5:319–328. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.5.3.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins ER. Constructive and unconstructive repetitive thought. Psychological Bulletin. 2008;134:163–206. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins ER, Scott J, Wingrove J, Rimes K, Bathurst N, Steiner H, et al. Rumination-focused cognitive behaviour therapy for residual depression: A case series. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:2144–2154. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D. Rethinking the mood and anxiety disorders: A quantitative hierarchical model for DSM-V. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:522–536. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA. Negative affectivity: the disposition to experience aversive emotional states. Psychological Bulletin. 1984;96:465–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]