Abstract

Glenohumeral motion presents challenges for its accurate description across all available ranges of motion using conventional Euler/Cardan angle sequences without singularity. A comparison of the description of glenohumeral motion was made using the ISB recommended YX’Y” sequence to the XZ’Y” sequence. A direct in-vivo method was used for the analysis of dynamic concentric glenohumeral joint motion in the scapular plane. An electromagnetic tracking system collected data from ten healthy individuals while raising their arm. There were differences in the description of angular position data between the two different sequences. The YX’Y” sequence described the humerus to be in a more anteriorly rotated and externally rotated position compared to XZ’Y” sequence, especially, at lower elevation angles. The description of motion between increments using XZ’Y” sequence displacement decomposition was comparable to helical angles in magnitude and direction for the study of arm elevation in the scapular plane. The description of the direction or path of motion of the plane of elevation using YX’Y” angle decomposition would be contrary to that obtained using helical angles. We recommend that this alternate sequence (XZ’Y”) should be considered for describing glenohumeral motion.

Keywords: Euler/Cardan angles, Gimbal-lock, Helical angles, Glenohumeral, Kinematics

Introduction

Euler or Cardan angle sequences, or their joint coordinate system equivalents, are the most common and recommended method for mathematical estimation of three-dimensional (3-D) joint motion (Wu et al., 2002, 2005). These descriptors define joint position as a set of sequential rotations about three axes that are typically anatomically aligned (Wei et al, 1993, Wu et al., 2005). These descriptors provide a relatively easier calculation for non-redundant clinically interpretable joint position information; therefore, they are often chosen over other methods such as helical angles (Woltring, 1994), or rotation matrices. However, twelve possible sequences provide correct, though different descriptions of the same position (Woltring, 1991, 1994). Subsequently, the standardization and terminology committee of the International Society of Biomechanics (ISB) has recommended selection of a particular sequence for describing position for specific human joints. The recommended sequence is typically based on avoidance of singular positions within the normal range of motion, while also allowing clinical interpretation of motion (Karduna et al., 2000, Wu et al., 2005). This is challenging for the glenohumeral joint as no single sequence satisfies the criterion to describe all glenohumeral motions across all available ranges accurately and without singularity (Šenk & Chèze, 2005).

Euler or Cardan sequences describe an angular position, rather than the actual path of motion taken to arrive at that position (Woltring, 1991). However, it is common for authors to use the difference between the final and initial position to describe the range or direction of motion. (Andel et al., 2008; Bourne et al., 2007; Levasseur et al., 2007, Ludewig et al., 2009; Petusky et al., 2007). Woltring (1991) suggested that it is justifiable to treat rotations as vectorial only for very small angular movements. The joint orientations obtained from matrix calculations cannot be linearly added or subtracted to estimate the trajectory/range of motion’. This path of motion interpretation is common in the literature because it is important to understand how motion is produced or restricted. Choosing a rotation sequence that most closely describes the path of motion is challenging, particularly for joints with large ranges of motion in multiple directions.

The YX’Y” rotation sequence is recommended for the descriptions of glenohumeral motion. It describes the plane of elevation, elevation angle, and axial rotation of the humerus relative to the scapula (Wu et al., 2005). This sequence allows the second rotation (elevation) to pass through 90° without singularity. However, singular positions will occur at and approaching 0° and 180° (within 20°) of humeral elevation (Doorenbosch et al., 2003). Hence, the assessment of the plane of elevation and axial rotation (1st and 3rd rotations) are mathematically rendered inaccurate in the initial and final 20° of motion while analyzing arm elevation. Also, the YX’Y” rotation sequence is not plausible for evaluating humeral axial rotation with the arm at the side, which is routinely performed in clinical evaluations (Rundquist et al., 2003).

An alternate sequence for glenohumeral motion analysis has been used in the literature (Levasseur et al., 2007; Ludewig et al., 2000) (XZ’Y” sequence) which describes the angle of elevation, angle of horizontal adduction/abduction (or flexion/extension) and axial rotation. This sequence has the advantage of describing motion with 3 separate non-repeating axes. Šenk & Chèze (2005) recommended this sequence as the best sequence for evaluating elevation motions. However, comparison needs to be made between the angular descriptions using either of these rotations to the path of motion.

The path of motion analysis can be accomplished either using Cardan angle values from small increment displacement matrices (Zatsiorsky, 1998) or a helical angle approach (Woltring et al., 1991, Baeyens et al., 2005). One way to verify the clinical applicability for Euler/Cardan rotation sequences is to analyze a particular motion comparing the displacement angles and helical angles for that motion with the change in position data.

The purpose of this paper was to quantitatively compare the description of glenohumeral joint motion during abduction in the scapular plane between two Euler/Cardan sequences, as well as to the displacement and helical angles. Our hypotheses were that 1) we would obtain significantly different mathematical interpretations of the same glenohumeral motion by using different Euler/cardan angle sequences especially for the first and third order rotations because we would expect to reach gimbal lock position using the YX’Y” sequence during movement initiation; and 2) the XZ’Y” sequence would demonstrate greater clinical applicability by representing the path of motion (measured by displacement and helical angles) more closely than the YX’Y” sequence.

Materials and methods

The study was approved by The Human Subjects Institutional Review Board at the University of Minnesota. Ten healthy subjects with no history of shoulder pain were screened for absence of shoulder related pathologies (Table 1). Subjects for this investigation were recruited for a larger study (Ludewig et al., 2009). Subjects within 18 to 60 years of age were included if they had full pain free range of motion at the shoulder joint. They were excluded if they had any history of trauma, fracture, weakness, or dislocation of the shoulder joint, positive sulcus sign or apprehension test, or cervical radicular symptoms. Each subject read and signed a consent form prior to participation in the study.

Table 1.

Subject Demographics

| Mean ± SD | |

|---|---|

| Age | 30.3 years ± 7 |

| Gender | 6 males and 4 females |

| Weight | 75.5 Kgs ± 13.8 |

| Height | 174.5 cms ± 8.6 |

| Handedness | 1 left, 9 right handed |

| Side Tested | 2 dominant, 8 non-dominant |

The position and orientation of the humerus with reference to the scapula was obtained using the Flock of Birds® hardware (Ascension Technology Corporation, Burlington, VT) and Motion Monitor™ software (Innovative Sports Training, Inc., Chicago, IL). This electromagnetic system allowed simultaneous tracking of sensors at a sampling rate of 100 Hz. The reported accuracy for a static sensor is 1.8 mm for position and 0.5° for orientation.

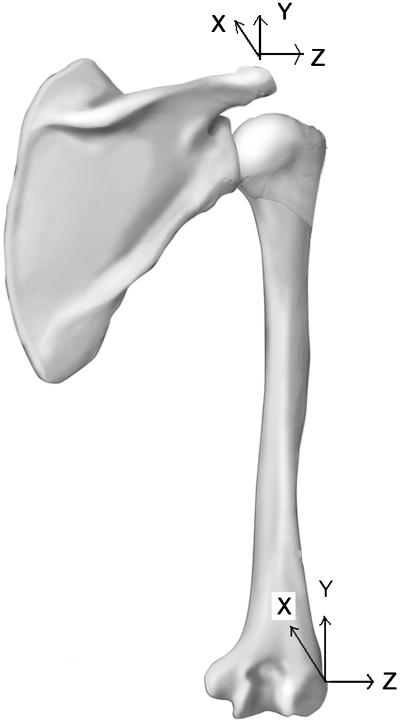

Small (mini-bird) electromagnetic tracking sensors were secured to bicortical pins inserted under local anesthetic and fluoroscopic guidance into the acromion process of the scapula and the humerus at the deltoid tuberosity (Ludewig et al., 2009). Another sensor was taped to the thorax. Bony landmarks were palpated and digitized using a stylus with known tip offsets to establish clinically meaningful joint axis orientations using ISB recommended protocols (Wu et al., 2005). The axes were formed such that the positive direction of the X axis was directed anteriorly, the Y axis was directed superiorly and the Z axis was directed laterally outwards (Figure 1). While guided by a flat planar surface, the subjects raised their arm in the scapular plane (40° anterior to the coronal plane), taking approximately 3 seconds for each of two repetitions.

Figure 1.

Local coordinate system for the scapula and the humerus with X axis pointing forward, Y axis pointing up and the Z axis pointing laterally.

Data Reduction and Analysis

Data collected from each sensor was transformed into the position and orientation of the respective anatomical coordinate system. The position of the humerus with respect to the scapula was described using the ISB recommended YX’Y” sequence and the alternate X’Z’Y” sequence for the positions of rest, 30°, 60°, 90° and 120° of humerothoracic elevation. Data from the two trials were averaged. The comparisons were made between the descriptions of plane of elevation as described by the first axis rotation of the YX’Y” sequence and the second axis rotation of the X’Z’Y” sequence (both of which define the position of the humerus anterior or posterior to the scapular plane); angle of elevation as described by the second axis rotation of the YX’Y” sequence and the first axis rotation of the XZ’Y” sequence; and axial rotation as described by the third axis rotation of both sequences.

The dependant variables were the amount of glenohumeral angular rotation about the 3 axes. A two way repeated measures ANOVA was performed for each dependant variable across the 2 sequences (YX’Y”/X’Z’Y”) and 5 humerothoracic elevation angles (Rest, 30°, 60°, 90° and 120°) with an overall significance level of p ≤ 0.05. In the presence of a significant interaction between sequence and elevation angle, the main effect of sequence was analyzed for each elevation angle by a one way ANOVA.

Helical angles were calculated to estimate the direction of motion for increments of motion (minimum point of elevation to 30°, 30° to 60°, 60° to 90° and 90° to 120° of humerothoracic elevation). Because helical angles are not as frequently used, to further compare with helical angles, displacement angles were also calculated using the XZ’Y” sequence (Engin, 1980, Zatsiorsky, 1998) for the same increments of the motion. This resulted in 4 increments of motion between the 5 positions. The directions of motion as defined by each of the two position angle sequences were then compared descriptively with the helical and displacement angles.

Descriptive data were also analyzed for single subject motions of coronal plane abduction and axial rotation with the arm adduction (from full internal to full external rotation). Analyses included calculations of angles using both rotation sequences, and helical angles.

Results

Comparisons of angular position data from two sequences

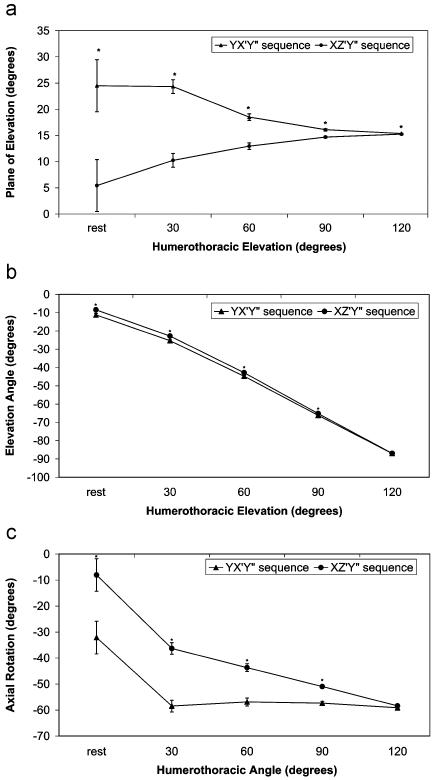

For each of the three rotational position comparisons, there was a significant interaction of method and angle of elevation (df 4, 36; p range= 0.0004 - 0.027; Figure 2a-c). This necessitated comparison at each elevation angle.

Figure 2.

a Comparison of plane of elevation using YX’Y” and XZ’Y” sequence. The values are given as mean and standard error. (*) indicates significant differences at p<0.05.

b Comparison of angle of elevation using YX’Y” and XZ’Y” sequence. The values are given as mean and standard error. (*) indicates significant differences at p<0.05.

c Comparison of axial rotation using YX’Y” and XZ’Y” sequence. The values are given as mean and standard error. (*) indicates significant differences at p<0.05.

There was a significant difference between the two sequences in the descriptions of positions of the humeral plane of elevation at all angles (Figure 2a). The magnitudes of these differences were reduced at higher angles of humeral elevation (less than 2° at 90° and 120° of humerothoracic elevation). The YX’Y” sequence described the humerus to be significantly more horizontally adducted or anterior to the plane of the scapula by 19° ± 5° at rest (p=0.02), 14° ± 2° at 30° (p<0.0001) and 5° ± 1° at 60° (p=0.0001) of humerothoracic elevation as compared to the XZ’Y” sequence (Figure 2a).

The YX’Y” sequence consistently described the elevation angle of the humerus to be slightly higher (less than 3°) than the angle described by the XZ’Y” sequence, except at 120° of humerothoracic elevation (Figure 2b). At 120°, no significant differences were found between the elevation angles as described by the two sequences (p =0.33).

As compared to the XZ’Y” sequence, the position of axial rotation of the humerus during arm elevation was consistently described by the YX’Y” sequence as more externally rotated. These sequence differences were greatest at the rest position (24° ± 6°, p=0.02) and progressively decreased with arm elevation at 30° (22° ± 2°, p<0.0001), 60° (13° ± 2°, p=0.0001) and 90° (6° ± 1°, p=0.0001). There were no differences in the angular descriptions of axial rotation at 120° of humerothoracic elevation (p= 0.3) (Figure 2c).

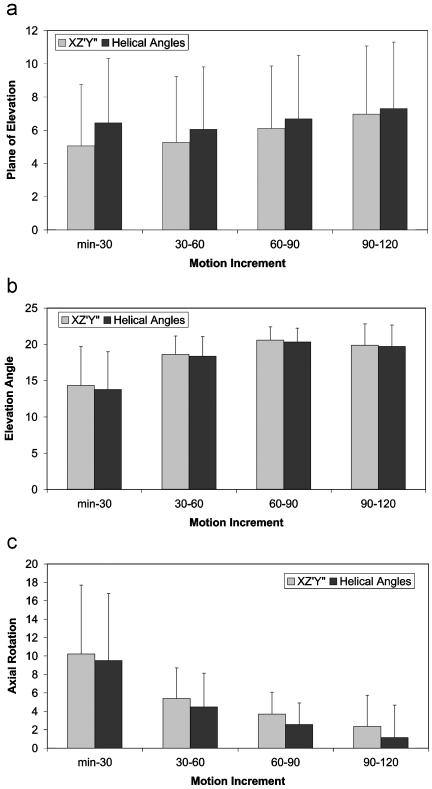

Comparisons of displacement data

The displacement decompositions using an XZ’Y” sequence were essentially equivalent to the helical angle displacements for all 3 angular rotations (Figure 3.) The largest difference between the two techniques was less than 1.5° (Figure 3a) for plane of elevation. By analyzing the direction and amplitudes of movement from helical angles, the pattern of glenohumeral motion can be deduced as a consistent elevation (approximately 15°-20°) through the motion increments. External rotation also occurs throughout the motion with the greatest increase for the minimum to 30° increment. Finally, consistent positive displacement occurs anterior to the plane of scapula (approximately 5°) through the motion increments. The trajectory of motion using the YX’Y” sequence decomposition would be described as increasing elevation, external rotation in the first increment of motion (~from 32° to 60°) and then a stable axial rotated position (~60° external rotation). Additionally, there was a decreasing plane of elevation angle (less anterior, from ~25° to 15°) (Figure 2 a-c).

Figure 3.

a Comparison of plane of elevation displacement decomposition using XZ’Y” sequence and helical angles. The values are given as mean and within group standard deviations.

b Comparison of angle of elevation displacement decomposition using XZ’Y” sequence and helical angles. The values are given as mean and within group standard deviations.

c Comparison of axial rotation displacement decomposition using XZ’Y” sequence and helical angles. The values are given as mean and within group standard deviations.

Discussion

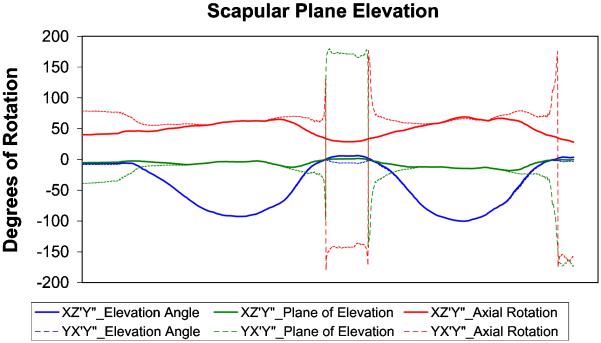

There are substantive differences (up to 24°) in the descriptions of glenohumeral position described by these different rotation sequences (Figure 2a and c, Table 2). The differences in angular position data for the plane of elevation and axial rotation (first and third axis rotations) were more significant at lower elevation angles because this position was closer to the gimbal lock position for the YX’Y” sequence. Gimbal lock is further illustrated in Figure 5 which shows data from a single subject performing scapular plane elevation. Discontinuities occur near gimbal lock positions in the descriptions of first and third axis rotations with the YX’Y” sequence.

Table 2.

Data (averaged over 2 repetitions) from a representative subject performing coronal plane elevation showing 1.the motion analyzed using XZ’Y” and YX’Y” rotation sequences and 2. linear subtraction between increments along with helical angles. Comparing the direction of motion for the plane of elevation rotation using XZ’Y” sequence and helical angles show a consistent motion posterior to the plane of the scapula (horizontal abduction) through the range whereas the description of the path of motion using YX’Y” sequence shows motion anterior to the plane of scapula (horizontal adduction)

| 1. Angular Position Data | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angle | XZ’Y” sequence | YX’Y” sequence | |||||||

| Elevation Angle |

Plane of Elevation |

Axial Rotation |

Elevation Angle |

Plane of Elevation |

Axial Rotation |

||||

| Min | −0.2° | 5.0° | −31.9° | −5.0° | 87.8° | −119.7° | |||

| 30° | −19.0° | −9.0° | −56.3° | −21.5° | −26.6° | −31.1° | |||

| 60° | −38.3° | −15.5° | −54.0° | −41.5° | −24.4° | −34.9° | |||

| 90° | −60.1° | −15.2° | −49.7° | −61.4° | −17.4° | −41.0° | |||

| 120° | −78.0° | −7.7° | −48.3° | −78.2° | −7.9° | −46.6° | |||

| 2. Linear subtraction between increments | |||||||||

|

Motion

Increments |

XZ’Y” sequence | YX’Y” sequence | Helical Angles | ||||||

| Elevation Angle |

Plane of Elevation |

Axial Rotation |

Elevation Angle |

Plane of Elevation |

Axial Rotation |

Elevation Angle |

Plane of Elevation |

Axial Rotation |

|

| Min-30° | −18.8° | −14.0° | −24.4° | −16.5° | −114.4 ° | 88.6° | −19.3° | −9.6° | −26.4° |

| 30°-60° | −19.3° | −6.6° | 2.3° | −20.0° | 2.2° | −3.8° | −18.5° | −6.7° | −1.1° |

| 60°-90° | −21.8° | 0.4° | 4.3° | −19.9° | 7.0° | −6.1° | −20.4° | −2.8° | 3.0° |

| 90°-120° | −17.9° | 7.5° | 1.4° | −16.8° | 9.5° | −5.6° | −18.1° | 1.3° | 7.4° |

Figure 5.

Data from a representative subject performing 2 repetitions of scapular plane elevation analyzed using XZ’Y” and YX’Y” rotation sequences. Discontinuities occur in the plane of elevation and axial rotation descriptions for the YX’Y” sequence when the elevation angle crosses or is near 0°, demonstrating gimbal lock. The XZ’Y” sequence describes the motion without discontinuities.

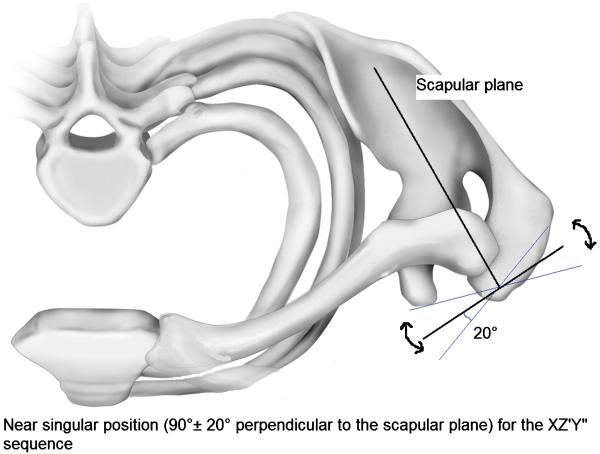

Šenk & Chèze (2005) investigated different Euler/Cardan angle sequences for glenohumeral motion based on avoidance of singularity. They found that the XZ’Y” sequence was the best to describe elevation of the humerus in the scapular or frontal planes. Also, there was no incidence of singularity for measuring motion when the arms did not the cross midline of the body in the direction of horizontal adduction. A recent study by Mazure et al. (2010) looked at different rotation sequences to describe the humerothoracic motion during a flat tennis serve and concluded that only the XZ’Y” sequence decomposition did not suffer from gimbal lock incidence for the analyzed motion. Our results are in agreement with these studies (Šenk & Chèze, 2005; Mazure et al., 2010) regarding the XZ’Y” sequence providing a better description of glenohumeral motion. A singular or near singular position with the XZ’Y” sequence would occur at 70-90° of rotation along second axis (horizontal adduction). The scapular plane lies close to 40° anterior to the coronal plane. For the descriptions of glenohumeral motions, it is unlikely to reach the singular position (≥110° of humerothoracic horizontal adduction) during most of the functional activities (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Superior view of shoulder joint showing near positions of singularity (90° ± 20° to scapular plane) when using the XZ’Y” sequence.

The YX”Y” sequence describes motion along an axis twice and we believe that this decomposition tends to misrepresent the actual joint motion. The direction of motion for the plane of elevation as would be analyzed by the trajectory of angular position data described by the conventional YX’Y” sequence was also contrary to the results obtained by helical angles (Figure 3a and 3c, Table 2). The trajectory could be interpreted as if during arm elevation there was a decrease in the horizontally adducted position of the arm, while, an increase in horizontal adduction was clearly described by helical angles. The description of motion demonstrated using XZ’Y” sequence was very similar to helical angles in both magnitude and direction for the group data of scapular plane abduction, and single subject data for coronal plane abduction.

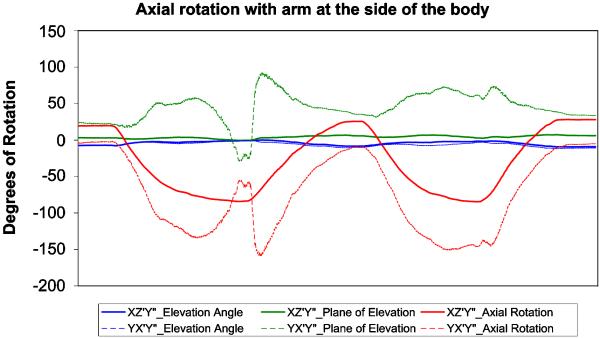

This YX’Y” Euler sequence can also be challenging for clinicians to interpret because the terminology is not common to clinical practice, and two of the three rotations are occurring about the same Y axis (although the second rotation is about a rotated first axis). This is a different description than rotations about three unique axes (flexion/extension, abduction/adduction, and internal/external rotation) that are more familiar to clinical practice. For example, in axial rotation with the arm at the side, a clinician would expect large changes in only axial rotation. However, as Figure 6 demonstrates, both 1st and 3rd rotations show large angular changes across the range of motion using YX’Y” sequence. Also the initial position of 0° of axial rotation is illogical clinically because the subject began the motion in internal rotation. This happens because the initial internal rotation position is described by the plane of elevation motion. Finally, as the angle of elevation is near zero (approaching gimbal lock), there are discontinuities in the data with abrupt changes from internal to external rotated positions. The alternative XZ’Y” is able to capture this same motion without discontinuity in a clinically interpretable manner.

Figure 6.

Data from a representative subject performing 2 repetitions of axial rotation with the arm at the side of the body analyzed using XZ’Y” and YX’Y” rotation sequences. Although the subject performed only axial rotation motion starting from full internal rotation, the YX’Y” sequence shows large rotations for both plane of elevation and axial rotation. Also, as the elevation angle approaches zero, there are discontinuities in the data such that it appears that the humerus changes the direction of motion to internal rotation. The alternative XZ’Y” is able to capture this same motion without discontinuity in a clinically interpretable manner.

It is not unusual to find in the literature that the trajectory of angular data is plotted against time to describe joint motion (Andel et al., 2008). Alternatively, authors have also used the difference of the maximum and minimum joint position data to describe the range of motion (Bourne et al., 2007; Andel et al., 2008; Petusky et al., 2007; Levasseur et al., 2007). For example, if the scapula were in a 20° internally rotated position at the time of initiating elevation and a 10° externally rotated position at peak elevation, then, the scapula would be considered to have moved 30° in the direction of external rotation. Karduna et al. (2000) showed that different conclusions could be drawn from the same scapular angular position data depending on the selection of sequence. Similar differences have also been shown at other joints (Baeyens et al., 2005). Our data indicates that such interpretations of glenohumeral motion using YX’Y” sequence would misrepresent the actual path of motion.

Overall, the results from this study and previous works (Karduna et al., 2000; Šenk & Chèze, 2005) emphasize the importance to present the information regarding the choice of rotation sequence used in the analysis. Additionally, researchers and clinicians should be cautious while comparing kinematic data based on different Euler/Cardan angle sequences.

This study has limitations. The study used bone-fixed sensors to measure joint kinematics, providing accurate representation without any skin motion artifact. However, low levels of pain (numerical pain score level < 2 out of 10) were induced (Ludewig et al., 2009). However, there was no indication that normal motion was altered (Braman et al., 2009). Moreover, as the same motion was analyzed using different mathematical descriptors, any motion alterations due to pain or digitization errors will not influence the comparison between rotation sequence descriptions. Due to the invasive nature of the study, the sample size was limited to 10 subjects, though this sample size was adequate to find even small significant differences between the methods of analysis for the position and displacement data. A final limitation was that the analysis was restricted to one motion of scapular plane elevation. In future work, the comparisons should be extended to other motions that are particularly challenging to interpret using the YX’Y” sequence. Presently, representative single subject data from coronal plane abduction motion (Table 2) as well as axial rotation with the arm at the side of the body (Figure 6) demonstrate issues with the use of the YX’Y” sequence.

There is not one ideal way to describe glenohumeral motions through all ranges and planes. However, the alternate XZ’Y” sequence could be appropriate for descriptions of arm raising and lowering motions and many functional tasks. The current YX’Y” sequence does not appear as well suited to describing glenohumeral elevation. The optimal description of a path of motion would incorporate displacement or helical angles in addition to position angles. The results of this study and that of Šenk & Chèze (2005) suggest further discussions are necessary regarding the selection of a sequence for the description of glenohumeral motions.

Acknowledgement

This study was funded by NIH grant # K01HD042491 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The authors would like to thank Cort J. Cieminksi, PhD, PT, ATC, CSCS; Daniel R Hassett, PT; Fred Wentorf, PhD; Ed Gonda; Michael McGinnitty and Kelly Kyle, for their assistance with completing various aspects of data collection and analysis for this project.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Andel CJ, Wolterbeek N, Doorenbosch CA, Veeger DH, Harlaar J. Complete 3D kinematics of upper extremity functional tasks. Gait and Posture. 2008;27(1):120–127. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeyens JP, Cattrysse E, Van Roy P, Clarys JP. Measurement of three-dimensional intra-articular kinematics: methodological and interpretation problems. Ergonomics. 2005;48(11-14):1638–1644. doi: 10.1080/00140130500101296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braman JP, Engel SC, LaPrade RF, Ludewig PM. In vivo assessment of scapulohumeral rhythm during unconstrained overhead reaching in asymptomatic subjects. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. 2009;18(6):960–967. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne DA, Choo MAT, Regan WD, MacIntyre DL, Oxland TR. Three-dimensional rotation of the scapula during functional movements: An in vivo study in healthy volunteers. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow surgery. 2007;16:150–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doorenbosch CA, Harlaar J, Veeger DH. The globe system: an unambiguous description of shoulder positions in daily life movements. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 2003;40(2):147–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engin AE. On the biomechanics of the shoulder complex. Journal of Biomechanics. 1980;13(7):575–590. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(80)90058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karduna AR, McClure PW, Michener LA. Scapular kinematics: effects of altering the Euler angle sequence of rotations. Journal of Biomechanics. 2000;33(9):1063–1068. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(00)00078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levasseur A, Tétreault P, Guise J, Nuño N, Hagemeister N. The effect of axis alignment on shoulder joint kinematics analysis during arm abduction. Clinical Biomechanics. 2007;22(7):758–766. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludewig PM, Cook TM. Alterations in shoulder kinematics and associated muscle activity in people with symptoms of shoulder impingement. Physical Therapy. 2000;80(3):276–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludewig PM, Phadke V, Braman JP, Hassett DR, Cieminski CJ, LaPrade RF. Motion of the shoulder complex during multiplanar humeral elevation. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. 2009;91(2):378–389. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazure AB, Slawinski J, Riquet A, Lévèque JM, Miller C, Chèze L. Rotation sequence is an important factor in shoulder kinematics. Application to the elite players’ flat serves. Journal of Biomechanics. 2010;43:2022–2035. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petuskey K, Bagley A, Abdala E, James MA, Rab G. Upper extremity kinematics during functional activities: three-dimensional studies in a normal pediatric population. Gait Posture. 2007;25(4):573–579. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rundquist PJ, Anderson DD, Guanche CA, Ludewig PM. Shoulder Kinematics in Subjects with Frozen Shoulder. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2003;84(10):1473–9. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(03)00359-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šenk M, Chèze L. Rotation sequence as an important factor in shoulder kinematics. Clinical Biomechanics. 2005;21(Suppl 1):S3–S8. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woltring HJ. Representation and calculation of 3-D joint movement. Human Movement Sciences. 1991;10:603–616. [Google Scholar]

- Woltring HJ. 3-D attitude representation of human joints: A standardization proposal. Journal of Biomechanics. 1994;27(12):1399–1414. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)90191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei SH, McQuade KJ, Smidt GL. Three-dimensional joint range of motion measurements from skeletal coordinate data. Journal of Orthopedic Sports Physical Therapy. 1993;18(6):687–91. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1993.18.6.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, et al. ISB recommendation on definitions of joint coordinate system of various joints for the reporting of human joint motion--part I: ankle, hip, and spine. International Society of Biomechanics. Journal of Biomechanics. 2002;35(4):543–8. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, et al. ISB recommendation on definitions of joint coordinate systems of various joints for the reporting of human joint motion--part II: Shoulder, elbow, wrist and hand. Journal of Biomechanics. 2005;38(5):981–992. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zatsiorsky VM. Kinematics of Human Motion. Human Kinetics; USA: 1998. Chapter 1. [Google Scholar]