Abstract

Endophytes are microorganisms that reside asymptomatically in the tissues of higher plants and are a promising source of novel organic natural metabolites exhibiting a variety of biological activities. The laboratory of Bioaromas (Unicamp, Brazil) develops research in biotransformation processes and functional evaluation of natural products. With the intent to provide subsidies for studies on endophytic microbes related to areas cited before, this paper focuses particularly on the role of endophytes on the production of anticancer, antimicrobial, and antioxidant compounds and includes examples that illustrate their potential for human use. It also describes biotransformation as an auspicious method to obtain novel bioactive compounds from microbes. Biotransformation allows the production of regio- and stereoselective compounds under mild conditions that can be labeled as “natural,” as discussed in this paper.

1. Introduction

The term “endophytes” includes a suite of microorganisms that grow intra-and/or intercelullarly in the tissues of higher plants without causing over symptoms on the plants in which they live, and have proven to be rich sources of bioactive natural products [1, 2]. Mutualism interaction between endophytes and host plants may result in fitness benefits for both partners [3]. The endophytes may provide protection and survival conditions to their host plant by producing a plethora of substances which, once isolated and characterized, may also have potential for use in industry, agriculture, and medicine [4, 5].

Approximately 300 000 plant species growing in unexplored area on the earth are host to one or more endophytes [6], and the presence of biodiverse endophytes in huge number plays an important role on ecosystems with greatest biodiversity, for instance, the tropical and temperate rainforests [5], which are extensively found in Brazil and possess almost 20% of its biotechnological source [7]. Considering that only a small amount of endophytes have been studied, recently, several research groups have been motivated to evaluate and elucidate the potential of these microorganisms applied on biotechnological processes focusing on the production of bioactive compounds.

The production of bioactive substances by endophytes is directly related to the independent evolution of these microorganisms, which may have incorporated genetic information from higher plants, allowing them to better adapt to plant host and carry out some functions such as protection from pathogens, insects, and grazing animals [6]. Endophytes are chemical synthesizer inside plants [8], in other words, they play a role as a selection system for microbes to produce bioactive substances with low toxicity toward higher organisms [6].

Bioactive natural compounds produced by endophytes have been promising potential usefulness in safety and human health concerns, although there is still a significant demand of drug industry for synthetic products due to economic and time-consuming reasons [4]. Problems related to human health such as the development of drug resistance in human pathogenic bacteria, fungal infections, and life threatening virus claim for new therapeutic agents for effective treatment of diseases in human, plants, and animals that are currently unmet [5, 6, 9].

Recent review by Newman and Cragg [10] presented a list of all approved agents from 1981 to 2006, from which a significant number of natural drugs are produced by microbes and/or endophytes. Endophytes provide a broad variety of bioactive secondary metabolites with unique structure, including alkaloids, benzopyranones, chinones, flavonoids, phenolic acids, quinones, steroids, terpenoids, tetralones, xanthones, and others [2]. Such bioactive metabolites find wide-ranging application as agrochemicals, antibiotics, immunosuppressants, antiparasitics, antioxidants, and anticancer agents [11].

Methods to obtain bioactive compounds include the extraction from a natural source, the microbial production via fermentation, or microbial transformation. Extraction from natural sources presents some disadvantages such as dependency on seasonal, climatic and political features and possible ecological problems involved with the extraction, thus calling for innovative approaches to obtain such compounds [12]. Hence, biotechnological techniques by using different microorganisms appear promising alternatives for establishing an inexhaustible, cost-effective and renewable resource of high-value bioactive products and aroma compounds. The biotransformation method has a huge number of applications [13], for instance, it has been extensively employed for the production of volatile compounds [12, 14, 15]. These volatile compounds possess not only sensory properties, but other desirable properties such as antimicrobial (vanillin, essential oil constituents), antifungal and antiviral (some alkanolides), antioxidant (eugenol, vanillin), somatic fat reducing (nootkatone), blood pressure regulating (2-[E]-hexenal), anti-inflammatory properties (1,8-cineole), and others [16].

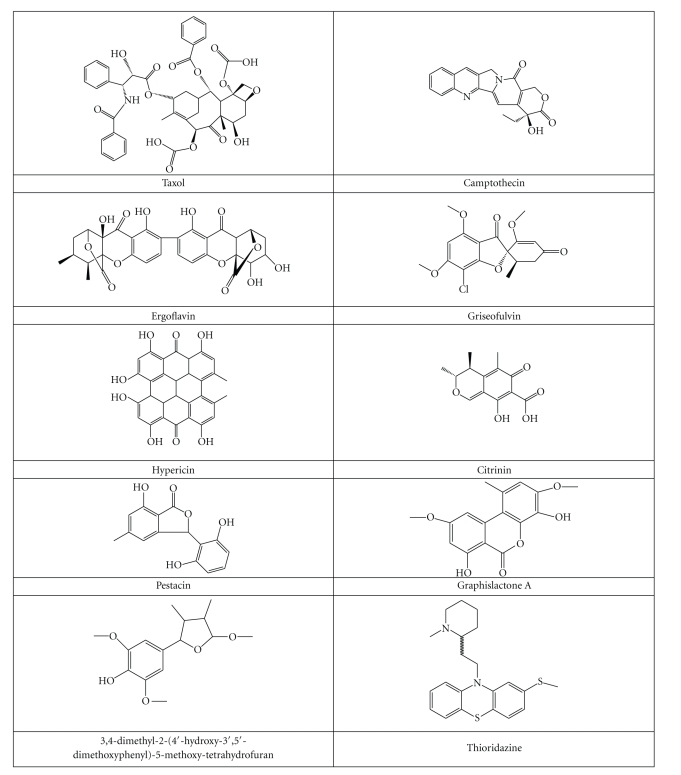

This paper focuses particularly on the role of endophytes in the production of bioactive compounds, the importance of including endophytic microbes in the screening approach for novel drugs, and the microbial biotransformation process as a novel alternative method to obtain such compounds. It also describes these compounds by different functions, including some examples that illustrate the potential for human use. Finally, structures of some compounds produced by endophytes are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Some structures obtained from endophytics microorganisms.

2. Anticancer Compounds

Cancer is a group of diseases characterized by unregulated growth and spread of abnormal cells, which can result in death if not controlled [17]. It has been considered one of the major causes of death worldwide: 7.4 million (about 13% of all deaths) in 2004 [18]. The anticancer drugs show nonspecific toxicity to proliferating normal cells, possess enormous side effects, and are not effective against many forms of cancer [19, 20]. Thus, the cure of cancer has been enhanced mainly due to diagnosis improvements which allow earlier and more precise treatments [20].

There are some evidences that bioactive compounds produced by endophytes could be alternative approaches for discovery of novel drugs, since many natural products from plants, microorganisms, and marine sources were identified as anticancer agents [21]. The anticancer properties of several secondary metabolites from endophytes have been investigated recently. Following, some examples of the potential of endophytes on the production of anticancer agents are cited.

The diterpenoid “Taxol” (also known in the literature as paclitaxel) have generated more attention and interest than any other new drug since its discovery, possibly due to its unique mode of action compared to other anticancer agents [19, 21]. This compound interferes with the multiplication of cancer cells, reducing or interrupting their growth and spreading. FDA (Food and Drug Administration) has approved Taxol for the treatment of advanced breast cancer, lung cancer, and refractory ovarian cancer [22]. Taxol (C47H51NO14) was firstly isolated from the bark of trees belonging to Taxus family (Taxus brevifolia), its most common source [23]. Nevertheless, these trees are rare, slow growing, and produce small amount of Taxol, which explain its high price in the market when obtained by this natural source [19]. Besides, in the context of environmental degradation, the use of plant source as unique option have limited the supply of this drug due to the destructive collection of yew trees [24]. Several reports about Taxol anticancer properties were published since its discovery [25–27], as well as other sources for production of Taxol have been investigated in the last decade.

The isolation of Taxol-producing endophyte Taxomyces andreanae has provided an alternative approach to obtain a cheaper and more available product via microorganism fermentation [28]. After that, Taxol has also been found in a number of different genera of fungal endophytes either associated or not to yews, such as Taxodium distichum [29]; Wollemia nobilis [30]; Phyllosticta spinarum [31]; Bartalinia robillardoides [19]; Pestalotiopsis terminaliae [32]; Botryodiplodia theobromae [33].

Another important anticancer compound is the alkaloid “Camptothecin” (C20H16N2O4), a potent antineoplastic agent which was firstly isolated from the wood of Camptotheca acuminata Decaisne (Nyssaceae) in China [34]. Camptothecin and 10-hydroxycamptothecin are two important precursors for the synthesis of the clinically useful anticancer drugs, topotecan, and irinotecan [35]. Although its potential use in medical treatments, the unmodified Camptothecin suffers from drawbacks that compromises its applications due to very low solubility in aqueous media and high toxicity [36, 37]. On the other hand, some Camptothecin derivatives retain the medicinal properties and can show other benefits without causing over drawbacks in some cases [38, 39]. Therefore, it is desirable to develop strategies for isolation, mixture separation, and production of Camptothecin and its analogues from novel endophytic fungal sources. The anticancer properties of the microbial products Camptothecin and two analogues (9-methoxycamptothecin and 10-hydroxycamptothecin) were already reported. The products were obtained from the endophytic fungi Fusarium solani isolated from Camptotheca acuminate [38]. Several reports have described other Camptothecin (or analogues) producing endophytes [40–44]. Since then, endophytes have been included in many studies purposing new approaches for drug discovery.

“Ergoflavin” (C30H26O14), a dimeric xanthene linked in position 2, belongs to the compound class called ergochromes and was described as a novel anticancer agent isolated from an endophytic fungi growing on the leaves of an Indian medicinal plant Mimusops elengi (Sapotaceae) [45]. “Secalonic acid D” (C32H30O14), a mycotoxin also belonging to ergochrome class, is known to have potent anticancer activities. It was isolated from the mangrove endophytic fungus and observed high cytotoxicity on HL60 and K562 cells by inducing leukemia cell apoptosis [46].

“Phenylpropanoids” have attracted much interest for medicinal use as anticancer, antioxidant, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and immunosuppressive properties [47]. Despite the phenylpropanoids belong to the largest group of secondary metabolites produced by plants, reports showed the production of such compounds by endophytes. The endophytic Penicillium brasilianum, found in root bark of Melia azedarach, promoted the biosynthesis of phenylpropanoid amides [48]. Likewise, two monolignol glucosides, coniferin and syringin, are produced not only by the host plant, but were also recognized by the endophytic Xylariaceae species as chemical signals during the establishment of fungus-plant interactions [49]. Koshino and coworkers characterized two phenylpropanoids and lignan from stromata of Epichloe typhina on Phleum pretense [50]. “Lignans” are other kinds of anticancer agents originated as secondary metabolites through the shikimic acid pathway and display different biological activities that make them interesting in several lines of research [51]. Although their molecular backbone consists only of two phenylpropane units (C6-C3), lignans show enormous structural and biological diversity, especially in cancer chemotherapy [47].

“Podophyllotoxin” (C22H22O8) and analogs are clinically relevant mainly due to their cytotoxicity and antiviral activities and are valued as the precursor to useful anticancer drugs like etoposide, teniposide, and etopophos phosphate [52, 53]. The aryl tetralin lignans, such as podophyllotoxin, are naturally synthesized by Podophyllum sps., however, alternative sources have been searched to avoid endangered plant. Another study showed a novel fungal endophyte, Trametes hirsute, that produces podophyllotoxin and other related aryl tetralin lignans with potent anticancer and properties [54]. Novel microbial sources of Podophyllotoxin were reported from the endophytic fungi Aspergillus fumigatus Fresenius isolated from Juniperus communis L. Horstmann [52], Phialocephala fortinii isolated from Podophyllum peltatum [55], and Fusarium oxysporum from Juniperus recurva [53].

Wagenaar and co-workers reported identification of three novel “cytochalasins”, bearing antitumor activity from the endophyte Rhinocladiella sp. [56]. Extensive experiments identified these new compounds as 22-oxa-12-cytochalasins. “Torreyanic acid” (C38H44O12) is an unusual dimeric quinone isolated from the endophytic fungus Pestalotiopsis microspora from T. taxifolia (Florida torreya) and was proven to have selective cytotoxicity 5 to 10 times more potent in cell lines that are sensitive to protein kinase C agonists and causes cell death by apoptosis [57]. “Gliocladicillins A” and “B” were reported as effective antitumor agents in vitro and in vivo, since they induced tumor cell apoptosis and showed significant inhibition on proliferation of melanoma B16 cells implanted into immunodeficient mice [58].

Crude Extracts of Alternaria alternata, an endophytic fungus isolated from Coffea Arabica L., displayed moderate cytotoxic activity towards HeLa cells in vitro, when compared to the dimethyl sulfoxide-(DMSO-) treated cells [59]. The investigation of endophytic actinomycetes associated with pharmaceutical plants in rainforest reported 41 microorganisms from the genus Streptomyces displayed significant antitumor activity against HL-60 cells, A549 cells, BEL-7404 cells, and P388D1 cells [1]. The screening of endophytic fungi isolated from pharmaceutical plants in China showed that 13.4% endophytes were cytotoxic on HL-60 cells and 6.4% on KB cells [60].

Finally, other compounds with anticancer properties isolated from endophytic microbes were reported such as “cytoskyrins” [61], “phomoxanthones A” and “B” [62], “photinides A-F” [63], “rubrofusarin B” [64], and “(+)-epiepoxydon” [65].

3. Antimicrobial Compounds

Metabolites bearing antibiotic activity can be defined as low-molecular-weight organic natural substances made by microorganisms that are active at low concentrations against other microorganisms [24]. Endophytes are believed to carry out a resistance mechanism to overcome pathogenic invasion by producing secondary metabolites [2]. So far, studies reported a large number of antimicrobial compounds isolated from endophytes, belonging to several structural classes like alkaloids, peptides, steroids, terpenoids, phenols, quinines, and flavonoids [66].

The discovery of novel antimicrobial metabolites from endophytes is an important alternative to overcome the increasing levels of drug resistance by plant and human pathogens, the insufficient number of effective antibiotics against diverse bacterial species, and few new antimicrobial agents in development, probably due to relatively unfavorable returns on investment [66, 67]. The antimicrobial compounds can be used not only as drugs by humankind but also as food preservatives in the control of food spoilage and food-borne diseases, a serious concern in the world food chain [68].

Many bioactive compounds, including antifungal agents, have been isolated from the genus Xylaria residing in different plant hosts, such as “sordaricin” with antifungal activity against Candida albicans [69]; “mellisol” and “1,8-dihydroxynaphthol 1-O-a-glucopyranoside” with activity against herpes simplex virus-type 1 [70]; “multiplolides A and B” with activity against Candida albicans [71]. The bioactive compound isolated from the culture extracts of the endophytic fungus Xylaria sp. YX-28 isolated from Ginkgo biloba L. was identified as “7-amino-4-methylcoumarin” [68]. The compound presented broad-spectrum inhibitory activity against several food-borne and food spoilage microorganisms including S. aureus, E. coli, S. typhia, S. typhimurium, S. enteritidis, A. hydrophila, Yersinia sp., V. anguillarum, Shigella sp., V. parahaemolyticus, C. albicans, P. expansum, and A. niger, especially to A. hydrophila, and was suggested to be used as natural preservative in food [68].

Another strain F0010 of the endophytic fungus Xylaria sp. from Abies holophylla was characterized as a producer of “griseofulvin” (C17H17ClO6), a spirobenzofuran antifungal antibiotic agent used for the treatment of human and veterinary animals mycotic diseases [72]. They evaluated and reported high antifungal activity in vivo and in vitro of the endophyte-produced griseofulvin against plant pathogenic fungi, controlling effectively the development of various food crops.

Aliphatic compounds, frequently detected in cultures of endophytes, often show biological activities. Four antifungal “aliphatic compounds” were characterized from stromata of E. typhina on P. pratense [73]. Two novel ester metabolites isolated from an endophyte of the eastern larch presented antimicrobial activity. One compound was toxic to spruce budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana Clem.) larvae, and the other may serve as potent antibacterial agent against Vibrio salmonicida, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Staphylococcus aureus [74].

Chaetomugilin A and D with antifungal activities, were isolated from an endophytic fungus C. globosum collected from Ginkgo biloba [75]. Cytosporone B and C were isolated from a mangrove endophytic fungus, Phomopsis sp. They inhibited two fungi C. albicans and F. oxysporum with the MIC value ranging from 32 to 64 mg·mL−1 [76].

Chlorinated metabolites such as (−)-mycorrhizin A, (+)-cryptosporiopsin isolated from endophytic Pezicula strains were reported as strongly fungicidal and herbicidal agents, and to a lesser extent, as algicidal and antibacterial agents [77]. Similarly, two other new chlorinated benzophenone derivatives, “Pestalachlorides A” (C21H21Cl2NO5) and “B” (C20H18Cl2O5), from the plant http://www.sciencedirect.com/ endophytic fungus Pestalotiopsis adusta, proven to display significant antifungal activity against three plant pathogenic fungi, Fusarium culmorum, Gibberella zeae, and Verticillium albo-atrum [78].

The production of “Hypericin” (C30H16O8), a naphthodianthrone derivative, and “Emodin” (C15H10O5) believed to be the main precursor of hypericin, by the endophytic fungus isolated from an Indian medicinal plant, was reported. Both compounds demonstrated antimicrobial activity against several bacteria and fungi, including Staphylococcus aureus ssp. aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae ssp. ozaenae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella enterica ssp. Enteric, and Escherichia coli, and fungal organisms Aspergillus niger and Candida albicans [79].

An endophytic Streptomyces sp. from a fern-leaved grevillea (Grevillea pteridifolia) in Australia was described as a promising producer of novel antibiotics, “kakadumycin A” and “echinomycin”. Kakadumycin A is structurally related to echinomycin, a quinoxaline antibiotic, and presents better bioactivity than echinomycin especially against Gram-positive bacteria and impressive activity against the malarial parasite Plasmodium falciparum [80].

More than 50% of endophytic fungi strains residing in Quercus variabilis possessed growth inhibition against at least one pathogenic fungi or bacteria. Cladosporium sp., displaying the most active antifungal activity, was investigated and found to produce a secondary metabolite known as “brefeldin A” (C16H24O4), a lactone with antibiotic activity. Results showed brefeldin A to be more potent than the positive control in antifungal activity [81].

“Coronamycin”, a peptide antibiotic produced by an endophytic fungi Streptomyces sp. isolated from Monstera sp., is active against pythiaceous fungi, the human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans, and the malarial parasite, Plasmodium falciparum [82]. Production of lipopeptide “pumilacidin”, an antifungal compound, by B. pumilus isolated from cassava cultivated by Brazilian Amazon Indian tribes was described for the first time [83]. The compounds “2-hexyl-3-methyl-butanodioic acid” and “cytochalasin D” were isolated from the endophytic fungus Xylaria sp. isolated from Brazilian Cerrado, and presented antifungal activity [84]. Two new bioactive metabolites, “ethyl 2,4-dihydroxy-5,6-dimethylbenzoate” and “phomopsilactone” were isolated from an endophytic fungus Phomopsis cassiae from Cassia spectabilis and displayed strong antifungal activity against two phytopathogenic fungi, Cladosporium cladosporioides, and C. sphaerospermum [85]. The polyketide “citrinin”, produced by endophytic fungus Penicillium janthinellum from fruits of Melia azedarach, presented 100% antibacterial activity against Leishmania sp. [86].

Among the 12 secondary metabolites produced by the endophytic fungi Aspergillus fumigatus CY018 isolated from the leaf of Cynodon dactylon, “asperfumoid”, “fumigaclavine C”,“fumitremorgin C”, “ physcion”, and “helvolic acid” were shown to inhibit Candida albicans [87]. Endophyte Verticillium sp. isolated from roots of wild Rehmannia glutinosa produced two compounds “2,6-Dihydroxy-2-methyl-7-(prop-1E-enyl)-1-benzofuran-3(2H)-one”, reported for the first time, and “ergosterol peroxide” with clear inhibition of the growth of three pathogens including Verticillium sp. [88]. An endophytic fungus Pestalotiopsis theae of an unidentified tree on Jianfeng Mountain, China, was capable of producing “Pestalotheol C” with anti-HIV properties [89].

Other secondary metabolites with antimicrobial properties isolated from endophytic microbes were reported like “3-O-methylalaternin” and “altersolanol A” [90], “phomoenamide” [91], “phomodione” [92], “ambuic acid” [93], “isopestacin” [6], and “munumbicin A, B, C” and “D” [94].

4. Antioxidant Compounds

The importance of compounds bearing antioxidant activity lays in the fact that they are highly effective against damage caused by reactive oxygen species (ROSs) and oxygen-derived free radicals, which contribute to a variety of pathological effects, for instance, DNA damages, carcinogenesis, and cellular degeneration [95, 96]. Antioxidants have been considered promising therapy for prevention and treatment of ROS-linked diseases as cancer, cardiovascular disease, atherosclerosis, hypertension, ischemia/reperfusion injury, diabetes mellitus, neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases), rheumatoid arthritis, and ageing [97]. Many antioxidant compounds possess anti-inflammatory, antiatherosclerotic, antitumor, antimutagenic, anticarcinogenic, antibacterial, or antiviral activities in higher or lower level [98–102].

Natural antioxidants are commonly found in medicinal plants, vegetables, and fruits. However, it has been reported that metabolites from endophytes can be a potential source of novel natural antioxidants. Liu and coworkers evaluated the antioxidant activity of an endophytic Xylaria sp. isolated from the medicinal plant Ginkgo biloba [103]. The results collected indicated that the methanol extract exhibited strong antioxidant capacity due to the presence of “phenolics” and “flavonoids” compounds among 41 identified compounds. Huang and coworkers investigated the antioxidant capacities of endophytic fungal cultures of medicinal Chinese plants and its correlation to their total phenolic contents. They suggested that the phenolic content were the major antioxidant constituents of the endophytes [95].

“Pestacin” (C15H14O4) and “isopestacin”, 1,3-dihydro isobenzofurans, were obtained from the endophytic fungus Pestalotiopsis microspora isolated from a plant growing in the Papua New Guinea, Terminalia morobensis [104, 105]. Besides antioxidant activity, pestacin and isopestacin also presented antimycotic and antifungal activities, respectively. Pestacin is believed to have antioxidant activity 11 times greater than Trolox, a vitamin E derivative, primarily via cleavage of an unusually reactive C-H bond and to a lesser extent, O-H abstraction [104]. Isopestacin possess antioxidant activity by scavenging both superoxide and hydroxy free radicals in solution, added to the fact that isopestacin is structurally similar to the flavonoids [105].

Polysaccharides from plants and microorganisms have been extensively studied and considered as potent natural antioxidants [58, 106–109]. Liu and coworkers reported, for the first time, the capacity of endophytic microorganisms to produce polysaccharides with antioxidant. The bacterium endophyte Paenibacillus polymyxa isolated from the root tissue of Stemona japonica Miquel, a traditional Chinese medicine, produced “exopolysaccharides (EPS)” that demonstrated strong scavenging activities on superoxide and hydroxyl radicals [110].

“Graphislactone A”, a phenolic metabolite isolated from the endophytic fungus Cephalosporium sp. IFB-E001 residing in Trachelospermum jasminoides, demonstrated to have free radical-scavenging and antioxidant activities in vitro stronger than the standards, butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) and ascorbic acid, coassayed in the study [111].

For more detailed information on antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anticancer agents from microbial source, the references Newman and Cragg [10] and Firáková and coworkers [21] are recommended.

5. Biotransformation Process

Biotransformation can be defined as the use of biological systems to produce chemical changes on compounds that are not their natural substrates [112]. The microbial growth, sustenance, and reproduction depends on the availability of a suitable form of reduced carbon source, used as chemical energy, which under normal conditions of culture broth are the common sugars. Nevertheless, microorganisms are believed to have no limit to adapt to new environments and to metabolize various foreign substrates to carbon and nitrogen sources [113]. A molecule can be modified by transforming functional groups, with or without degradation of carbon skeleton. Such modifications result in the formation of novel and useful products not easily prepared by chemical methods [13].

The biotransformation process provides a number of advantages over chemical synthesis. The process can be carried out under mild conditions like ambient temperature and without the need of high pressure and extreme conditions, thus reducing undesired byproduct, energy needs, and cost [114]. The region-and stereo-selectivity of the process allows the production of enantiomerically pure compounds, eliminating the need for complicated separation and purification steps [112, 115]. Besides, the reactions occur under ecologically acceptable conditions, with lower emission of industrial resides and production of biodegradable resides and products, thus reducing the environmental problems [12, 116]. Finally, the products obtained by biotransformation process can be labeled as “natural.” On the other hand, chemical synthesis often result in environmentally unfriendly production processes and lacks substrate selectivity, possibly causing the formation of undesirable reaction mixtures, and reducing process efficiency and increasing downstream cost [117].

Therefore, biotransformation is a useful method for production of novel compounds; enhancement in the productivity of a desired compound; overcoming the problems associated with chemical analysis; leading to basic information to elucidate the biosynthetic pathway [114]. For this reason, biotransformation using microbial cultures and/or their enzymatic systems alone has received increasing attention as a method for the conversion of lipids, monoterpenes, diterpenes, steroids, triterpenes, alkaloids, lignans, and some synthetic chemicals, carrying out stereospecific and stereoselective reactions for the production of novel bioactive molecules with some potential for pharmaceutical and food industries [13, 118].

Endophytic microorganisms are able to produce necessary enzymes for the colonization of plant tissues, and to use, at least in vitro, most plant nutrients and components [21]. Therefore, more recently, endophytes have received attention as biocatalysts in the chemical transformation of natural products and drugs, due to their ability to modify chemical structures with a high degree of stereospecificity and to produce known or novel enzymes that facilitates the production of compounds of interest. Although the high potential of these microorganisms, studies using endophytes in the field of biotransformation are still limited.

The biotransformation of a tetrahydrofuran lignan, (−)-grandisin, by the endophytic fungus Phomopsis sp. from Viguiera arenaria was demonstrated by Verza and coworkers [119]. The process led to the formation of a new compound named as “3,4-dimethyl-2-(4′-hydroxy-3′, 5′-dimethoxyphenyl)-5-methoxy-tetrahydrofuran”, which showed trypanocidal activity similar to its natural corresponding precursor against the causative agent of Chagas disease, the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. Zikmundová and coworkers reported an endophytic fungus isolated from the roots and shoots of Aphelandra tetragona, capable to transform benzoxazinones, 2-benzoxazolinone (BOA) and 2-hydroxy-1,4-benzoxazin-3-one (HBOA), into different series of compounds [120].

The use of endophytic fungi in the stereoselective kinetic biotransformation of “thioridazine (THD)”, a phenothiazine neuroleptic drug, was investigated. Results showed that these microorganisms are able to biomimic mammalian metabolism via biotransformation reactions [112]. Another study employed endophytic fungus on the biotransformation of “propranolol (Prop)” to obtain 4-OH-Prop active metabolite in enantiomerically pure form [13].

Another interesting topic in biotransformation process is the use of endophytes in the biotransformation of terpenes for production of novel compounds through enzymatic reactions carried out by these microbes. “Terpenes” are large class of bioactive secondary metabolites used in the fragrance and flavor industries, and have been extensively used in biotransformation process by microorganisms with focus on the discovery of novel flavor compounds and on the optimization of the process condition [12]. Microbial transformations of terpenes were published recently using R-(+)-limonene [14, 121], L-menthol [122], α- and β-pinene [123, 124], and α-farnesene [15], by diverse microorganisms. However, some research groups have also investigated studies with the biotransformation of terpenes by endophytes.

Other endophytic microbes were studied for the capability to biotransform natural products like taxoids [125], alkaloids [126], pigment curcumim [127], betulinic, and betulonic acids [128].

6. Conclusion

Endophytes have proven to be rich sources of novel natural compounds with a wide-spectrum of biological activities and a high level of structural diversity. The use of endophytes as biocatalysts in the biotransformation process of natural products assumes greater importance. However, the application of microorganisms by the food and pharmaceutical industries to obtain compounds of interest is still modest, considering the great availability of useful microorganisms and the large scope of reactions that can be accomplished by them.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) for the financial support.

References

- 1.Li J, Zhao G-Z, Chen H-H, et al. Antitumour and antimicrobial activities of endophytic streptomycetes from pharmaceutical plants in rainforest. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 2008;47(6):574–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2008.02470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan RX, Zou WX. Endophytes: a rich source of functional metabolites. Natural Product Reports. 2001;18(4):448–459. doi: 10.1039/b100918o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kogel K-H, Franken P, Hückelhoven R. Endophyte or parasite—what decides? Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2006;9(4):358–363. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strobel G, Daisy B, Castillo U, Harper J. Natural products from endophytic microorganisms. Journal of Natural Products. 2004;67(2):257–268. doi: 10.1021/np030397v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strobel G, Daisy B. Bioprospecting for microbial endophytes and their natural products. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2003;67(4):491–502. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.4.491-502.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strobel GA. Endophytes as sources of bioactive products. Microbes and Infection. 2003;5(6):535–544. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(03)00073-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Souza AQL, Souza ADL, Astolfi Filho S, Belém Pinheiro ML, Sarquis MIM, Pereira JO. Atividade antimicrobiana de fungos endofíticos isolados de plantas tóxicas da Amazônia: Palicourea longiflora (aubl.) rich e Strychnos cogens bentham. ACTA Amazônica. 2004;34:185–195. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Owen NL, Hundley N. Endophytes—the chemical synthesizers inside plants. Science Progress. 2004;87(2):79–99. doi: 10.3184/003685004783238553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang L, An R, Wang J, et al. Exploring novel bioactive compounds from marine microbes. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 2005;8(3):276–281. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs over the last 25 years. Journal of Natural Products. 2007;70(3):461–477. doi: 10.1021/np068054v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gunatilaka AAL. Natural products from plant-associated microorganisms: distribution, structural diversity, bioactivity, and implications of their occurrence. Journal of Natural Products. 2006;69(3):509–526. doi: 10.1021/np058128n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bicas JL, Dionísio AP, Pastore GM. Bio-oxidation of terpenes: an approach for the flavor industry. Chemical Reviews. 2009;109(9):4518–4531. doi: 10.1021/cr800190y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Borges KB, Borges WDS, Durán-Patrón R, Pupo MT, Bonato PS, Collado IG. Stereoselective biotransformations using fungi as biocatalysts. Tetrahedron Asymmetry. 2009;20(4):385–397. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bicas JL, Barros FFC, Wagner R, Godoy HT, Pastore GM. Optimization of R-(+)-α-terpineol production by the biotransformation of R-(+)-limonene. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2008;35(9):1061–1070. doi: 10.1007/s10295-008-0383-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krings U, Hardebusch B, Albert D, Berger RG, Maróstica M, Jr., Pastore GM. Odor-active alcohols from the fungal transformation of α-farnesene. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2006;54(24):9079–9084. doi: 10.1021/jf062089j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berger RG. Biotechnology of flavours-the next generation. Biotechnology Letters. 2009;31(11):1651–1659. doi: 10.1007/s10529-009-0083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2009. American Cancer Society, Atlanta, Ga, USA, 2009.

- 18.WHO Mortality Database. Fact sheet No. 297. February 2009.

- 19.Gangadevi V, Muthumary J. Taxol, an anticancer drug produced by an endophytic fungus Bartalinia robillardoides Tassi, isolated from a medicinal plant, Aegle marmelos Correa ex Roxb. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2008;24(5):717–724. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pasut G, Veronese FM. PEG conjugates in clinical development or use as anticancer agents: an overview. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2009;61(13):1177–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Firáková S, Šturdíková M, Múčková M. Bioactive secondary metabolites produced by microorganisms associated with plants. Biologia. 2007;62(3):251–257. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cremasco MA, Hritzko BJ, Linda Wang N-H. Experimental purification of paclitaxel from a complex mixture of taxanes using a simulated moving bed. Brazilian Journal of Chemical Engineering. 2009;26(1):207–218. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wani MC, Taylor HL, Wall ME, Coggon P, McPhail AT. Plant antitumor agents. VI. The isolation and structure of taxol, a novel antileukemic and antitumor agent from Taxus brevifolia. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1971;93(9):2325–2327. doi: 10.1021/ja00738a045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo B, Wang Y, Sun X, Tang K. Bioactive natural products from endophytes: a review. Applied Biochemistry and Microbiology. 2008;44(2):136–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu H, Li B, Kang Y, et al. Paclitaxel nanoparticle inhibits growth of ovarian cancer xenografts and enhances lymphatic targeting. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology. 2006;59(2):175–181. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0256-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kakolyris S, Agelidou A, Androulakis N, et al. Cisplatin plus etoposide chemotherapy followed by thoracic irradiation and paclitaxel plus cisplatin consolidation therapy for patients with limited stage small cell lung carcinoma. Lung Cancer. 2006;53(1):59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peltier S, Oger J-M, Lagarce F, Couet W, Benoît J-P. Enhanced oral paclitaxel bioavailability after administration of paclitaxel-loaded lipid nanocapsules. Pharmaceutical Research. 2006;23(6):1243–1250. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-0022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stierle A, Strobel G, Stierle D. Taxol and taxane production by Taxomyces andreanae, an endophytic fungus of Pacific yew. Science. 1993;260(5105):214–216. doi: 10.1126/science.8097061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li J-Y, Strobel G, Sidhu R, Hess WM, Ford EJ. Endophytic taxol-producing fungi from bald cypress, Taxodium distichum. Microbiology. 1996;142(8):2223–2226. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-8-2223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strobel GA, Hess WM, Li J-Y, et al. Pestalotiopsis guepinii, a taxol-producing endophyte of the wollemi pine, Wollemia nobilis. Australian Journal of Botany. 1997;45(6):1073–1082. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumaran RS, Muthumary J, Hur BK. Production of taxol from Phyllosticta spinarum, an endophytic fungus of Cupressus sp. Engineering in Life Sciences. 2008;8(4):438–446. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gangadevi V, Muthumary J. Taxol production by Pestalotiopsis terminaliae, an endophytic fungus of Terminalia arjuna (arjun tree) Biotechnology and Applied Biochemistry. 2009;52(1):9–15. doi: 10.1042/BA20070243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pandi M, Manikandan R, Muthumary J. Anticancer activity of fungal taxol derived from Botryodiplodia theobromae Pat., an endophytic fungus, against 7, 12 dimethyl benz(a)anthracene (DMBA)-induced mammary gland carcinogenesis in Sprague dawley rats. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy. 2010;64:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wall ME, Wani MC, Cook CE, Palmer KH, McPhail AT, Sim GA. Plant antitumor agents. I. The isolation and structure of camptothecin, a novel alkaloidal leukemia and tumor inhibitor from Camptotheca acuminata. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1966;88(16):3888–3890. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uma SR, Ramesha BT, Ravikanth G, Rajesh PG, Vasudeva R, Ganeshaiah KN. Chemical profiling of N. nimmoniana for camptothecin, an important anticancer alkaloid: towards the development of a sustainable production system. In: Ramawat KG, Merillion J, editors. Bioactive Molecules and Medicinal Plants. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2008. pp. 198–210. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li Q-Y, Zu Y-G, Shi R-Z, Yao L-P. Review camptothecin: current perspectives. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2006;13(17):2021–2039. doi: 10.2174/092986706777585004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kehrer DFS, Soepenberg O, Loos WJ, Verweij J, Sparreboom A. Modulation of camptothecin analogs in the treatment of cancer: a review. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 2001;12(2):89–105. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200102000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kusari S, Zühlke S, Spiteller M. An endophytic fungus from Camptotheca acuminata that produces camptothecin and analogues. Journal of Natural Products. 2009;72(1):2–7. doi: 10.1021/np800455b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jew S-S, Kim H-J, Goo Kim M, et al. Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxicity of hexacyclic Camptothecin analogues. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 1999;9(22):3203–3206. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(99)00555-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shweta S, Zuehlke S, Ramesha BT, et al. Endophytic fungal strains of Fusarium solani, from Apodytes dimidiata E. Mey. ex Arn (Icacinaceae) produce camptothecin, 10-hydroxycamptothecin and 9-methoxycamptothecin. Phytochemistry. 2010;71(1):117–122. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu K, Ding X, Deng B, Chen W. 10-Hydroxycamptothecin produced by a new endophytic Xylaria sp., M20, from Camptotheca acuminata. Biotechnology Letters. 2010;32(5):689–693. doi: 10.1007/s10529-010-0201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rehman S, Shawl AS, Kour A, et al. An endophytic Neurospora sp. from Nothapodytes foetida producing camptothecin. Applied Biochemistry and Microbiology. 2008;44(2):203–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amna T, Puri SC, Verma V, et al. Bioreactor studies on the endophytic fungus entrophospora infrequens for the production of an anticancer alkaloid camptothecin. Canadian Journal of Microbiology. 2006;52(3):189–196. doi: 10.1139/w05-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Puri SG, Verma V, Amna T, Qazi GN, Spiteller M. An endophytic fungus from Nothapodytes foetida that produces camptothecin. Journal of Natural Products. 2005;68(12):1717–1719. doi: 10.1021/np0502802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deshmukh SK, Mishra PD, Kulkarni-Almeida A, et al. Anti-inflammatory and anticancer activity of ergoflavin isolated from an endophytic fungus. Chemistry and Biodiversity. 2009;6(5):784–789. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200800103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang J-Y, Tao L-Y, Liang Y-J, et al. Secalonic acid D induced leukemia cell apoptosis and cell cycle arrest of G1 with involvement of GSK-3β/β-catenin/c-Myc pathway. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(15):2444–2450. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.15.9170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Korkina LG. Phenylpropanoids as naturally occurring antioxidants: from plant defense to human health. Cellular and Molecular Biology. 2007;53(1):15–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fill TP, da Silva BF, Rodrigues-Fo E. Biosynthesis of phenylpropanoid amides by an endophytic penicillium brasilianum found in root bark of Melia azedarach. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2010;20(3):622–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chapela IH, Petrini O, Hagmann L. Monolignol glucosides as specific recognition messengers in fungus-plant symbioses. Physiological and Molecular Plant Pathology. 1991;39(4):289–298. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koshino H, Terada S-I, Yoshihara T, et al. Three phenolic acid derivatives from stromata of Epichloe typhina on Phleum pratense. Phytochemistry. 1988;27(5):1333–1338. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gordaliza M, García PA, Miguel Del Corral JM, Castro MA, Gómez-Zurita MA. Podophyllotoxin: distribution, sources, applications and new cytotoxic derivatives. Toxicon. 2004;44(4):441–459. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kusari S, Lamshöft M, Spiteller M. Aspergillus fumigatus Fresenius, an endophytic fungus from Juniperus communis L. Horstmann as a novel source of the anticancer pro-drug deoxypodophyllotoxin. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2009;107(3):1019–1030. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kour A, Shawl AS, Rehman S, et al. Isolation and identification of an endophytic strain of Fusarium oxysporum producing podophyllotoxin from Juniperus recurva. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2008;24(7):1115–1121. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Puri SC, Nazir A, Chawla R, et al. The endophytic fungus Trametes hirsuta as a novel alternative source of podophyllotoxin and related aryl tetralin lignans. Journal of Biotechnology. 2006;122(4):494–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eyberger AL, Dondapati R, Porter JR. Endophyte fungal isolates from Podophyllum peltatum produce podophyllotoxin. Journal of Natural Products. 2006;69(8):1121–1124. doi: 10.1021/np060174f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wagenaar MM, Corwin J, Strobel G, Clardy J. Three new cytochalasins produced by an endophytic fungus in the genus Rhinocladiella. Journal of Natural Products. 2000;63(12):1692–1695. doi: 10.1021/np0002942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lee JC, Strobel GA, Lobkovsky E, Clardy J. Torreyanic acid: a selectively cytotoxic quinone dimer from the endophytic fungus Pestalotiopsis microspora. Journal of Organic Chemistry. 1996;61(10):3232–3233. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen Y, Guo H, Du Z, Liu X-Z, Che Y, Ye X. Ecology-based screen identifies new metabolites from a Cordyceps-colonizing fungus as cancer cell proliferation inhibitors and apoptosis inducers. Cell Proliferation. 2009;42(6):838–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2009.00636.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fernandes MDRV, Silva TAC, Pfenning LH, et al. Biological activities of the fermentation extract of the endophytic fungus Alternaria alternata isolated from Coffea arabica L. Brazilian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2009;45(4):677–685. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang Y, Wang J, Li G, Zheng Z, Su W. Antitumor and antifungal activities in endophytic fungi isolated from pharmaceutical plants Taxus mairei, Cephalataxus fortunei and Torreya grandis. FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology. 2001;31(2):163–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2001.tb00513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brady SF, Singh MP, Janso JE, Clardy J. Cytoskyrins A and B, new BIA active bisanthraquinones isolated from an endophytic fungus. Organic Letters. 2000;2(25):4047–4049. doi: 10.1021/ol006681k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Isaka M, Jaturapat A, Rukseree K, Danwisetkanjana K, Tanticharoen M, Thebtaranonth Y. Phomoxanthones A and B, novel xanthone dimers from the endophytic fungus Phomopsis species. Journal of Natural Products. 2001;64(8):1015–1018. doi: 10.1021/np010006h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ding G, Zheng Z, Liu S, Zhang H, Guo L, Che Y. Photinides A-F, cytotoxic benzofuranone-derived γ-lactones from the plant endophytic fungus Pestalotiopsis photiniae. Journal of Natural Products. 2009;72(5):942–945. doi: 10.1021/np900084d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Song YC, Li H, Ye YH, Shan CY, Yang YM, Tan RX. Endophytic naphthopyrone metabolites are co-inhibitors of xanthine oxidase, SW1116 cell and some microbial growths. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2004;241(1):67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Klemke C, Kehraus S, Wright AD, König GM. New secondary metabolites from the marine endophytic fungus Apiospora montagnei. Journal of Natural Products. 2004;67(6):1058–1063. doi: 10.1021/np034061x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yu H, Zhang L, Li L, et al. Recent developments and future prospects of antimicrobial metabolites produced by endophytes. Microbiological Research. 2010;165(6):437–449. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Song J-H. What’s new on the antimicrobial horizon? International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 2008;32(4):S207–S213. doi: 10.1016/S0924-8579(09)70004-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Liu X, Dong M, Chen X, Jiang M, Lv X, Zhou J. Antimicrobial activity of an endophytic Xylaria sp.YX-28 and identification of its antimicrobial compound 7-amino-4-methylcoumarin. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2008;78(2):241–247. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1305-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pongcharoen W, Rukachaisirikul V, Phongpaichit S, et al. Metabolites from the endophytic fungus Xylaria sp. PSU-D14. Phytochemistry. 2008;69(9):1900–1902. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pittayakhajonwut P, Suvannakad R, Thienhirun S, Prabpai S, Kongsaeree P, Tanticharoen M. An anti-herpes simplex virus-type 1 agent from Xylaria mellisii (BCC 1005) Tetrahedron Letters. 2005;46(8):1341–1344. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Boonphong S, Kittakoop P, Isaka M, Pittayakhajonwut D, Tanticharoen M, Thebtaranonth Y. Multiplolides A and B, new antifungal 10-membered lactones from Xylaria multiplex. Journal of Natural Products. 2001;64(7):965–967. doi: 10.1021/np000291p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Park J-H, Choi GJ, Lee HB, et al. Griseofulvin from Xylaria sp. strain F0010, an endophytic fungus of Abies holophylla and its antifungal activity against plant pathogenic fungi. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2005;15(1):112–117. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Koshino H, Yoshihara T, Sakamura S, Shimanuki T, Sato T, Tajimi A. Novel C-11 epoxy fatty acid from stromata of Epichloe typhina on Phleum pratense. Agricultural Biology and Chemistry. 1989;53:2527–2528. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Findlay JA, Li G, Johnson JA. Bioactive compounds from an endophytic fungus from eastern larch (Larix laricina) needles. Canadian Journal of Chemistry. 1997;75(6):716–719. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Qin J-C, Zhang Y-M, Gao J-M, et al. Bioactive metabolites produced by Chaetomium globosum, an endophytic fungus isolated from Ginkgo biloba. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2009;19(6):1572–1574. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Huang Z, Cai X, Shao C, et al. Chemistry and weak antimicrobial activities of phomopsins produced by mangrove endophytic fungus Phomopsis sp. ZSU-H76. Phytochemistry. 2008;69(7):1604–1608. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Schulz B, Sucker J, Aust HJ, et al. Biologically active secondary metabolites of endophytic Pezicula species. Mycological Research. 1995;99(8):1007–1015. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li E, Jiang L, Guo L, Zhang H, Che Y. Pestalachlorides A-C, antifungal metabolites from the plant endophytic fungus Pestalotiopsis adusta. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry. 2008;16(17):7894–7899. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.07.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kusari S, Lamshöft M, Zühlke S, Spiteller M. An endophytic fungus from Hypericum perforatum that produces hypericin. Journal of Natural Products. 2008;71(2):159–162. doi: 10.1021/np070669k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Castillo U, Harper JK, Strobel GA, et al. Kakadumycins, novel antibiotics from Streptomyces sp. NRRL 30566, an endophyte of Grevillea pteridifolia. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2003;224(2):183–190. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00426-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang FW, Jiao RH, Cheng AB, Tan SH, Song YC. Antimicrobial potentials of endophytic fungi residing in Quercus variabilis and brefeldin A obtained from Cladosporium sp. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2007;23(1):79–83. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ezra D, Castillo UF, Strobel GA, et al. Coronamycins, peptide antibiotics produced by a verticillate Streptomyces sp. (MSU-2110) endophytic on Monstera sp. Microbiology. 2004;150(4):785–793. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26645-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.de Melo FMP, Fiore MF, de Moraes LAB, et al. Antifungal compound produced by the cassava endophyte Bacillus pumilus MAIIIM4A. Scientia Agricola. 2009;66(5):583–592. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cafêu MC, Silva GH, Teles HL, et al. Antifungal compounds of Xylaria sp., an endophytic fungus isolated from Palicourea marcgravii (Rubiaceae) Quimica Nova. 2005;28(6):991–995. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Silva GH, Teles HL, Trevisan HC, et al. New bioactive metabolites produced by Phomopsis cassiae, an endophytic fungus in Cassia spectabilis. Journal of the Brazilian Chemical Society. 2005;16(6 B):1463–1466. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Marinho AMR, Rodrigues-Filho E, Moitinho MDLR, Santos LS. Biologically active polyketides produced by Penicillium janthinellum isolated as an endophytic fungus from fruits of Melia azedarach. Journal of the Brazilian Chemical Society. 2005;16(2):280–283. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Liu JY, Song YC, Zhang Z, et al. Aspergillus fumigatus CY018, an endophytic fungus in Cynodon dactylon as a versatile producer of new and bioactive metabolites. Journal of Biotechnology. 2004;114(3):279–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.You F, Han T, Wu J-Z, Huang B-K, Qin L-P. Antifungal secondary metabolites from endophytic Verticillium sp. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology. 2009;37(3):162–165. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Li E, Tian R, Liu S, Chen X, Guo L, Che Y. Pestalotheols A-D, bioactive metabolites from the plant endophytic fungus Pestalotiopsis theae. Journal of Natural Products. 2008;71(4):664–668. doi: 10.1021/np700744t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Aly AH, Edrada-Ebel R, Wray V, et al. Bioactive metabolites from the endophytic fungus Ampelomyces sp. isolated from the medicinal plant Urospermum picroides. Phytochemistry. 2008;69(8):1716–1725. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rukachaisirikul V, Sommart U, Phongpaichit S, Sakayaroj J, Kirtikara K. Metabolites from the endophytic fungus Phomopsis sp. PSU-D15. Phytochemistry. 2008;69(3):783–787. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hoffman AM, Mayer SG, Strobel GA, et al. Purification, identification and activity of phomodione, a furandione from an endophytic Phoma species. Phytochemistry. 2008;69(4):1049–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Li JY, Harper JK, Grant DM, et al. Ambuic acid, a highly functionalized cyclohexenone with antifungal activity from Pestalotiopsis spp. and Monochaetia sp. Phytochemistry. 2001;56(5):463–468. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00408-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Castillo UF, Strobel GA, Ford EJ, et al. Munumbicins, wide-spectrum antibiotics produced by Streptomyces NRRL 30562, endophytic on Kennedia nigriscans. Microbiology. 2002;148(9):2675–2685. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-9-2675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Huang W-Y, Cai Y-Z, Xing J, Corke H, Sun M. A potential antioxidant resource: endophytic fungi from medicinal plants. Economic Botany. 2007;61(1):14–30. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Seifried HE, Anderson DE, Fisher EI, Milner JA. A review of the interaction among dietary antioxidants and reactive oxygen species. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2007;18(9):567–579. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MTD, Mazur M, Telser J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. International Journal of Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 2007;39(1):44–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Owen RW, Giacosa A, Hull WE, Haubner R, Spiegelhalder B, Bartsch H. The antioxidant/anticancer potential of phenolic compounds isolated from olive oil. European Journal of Cancer. 2000;36(10):1235–1247. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00103-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cozma LS. The role of antioxidant therapy in cardiovascular disease. Current Opinion in Lipidology. 2004;15(3):369–371. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200406000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Halliwell B. Free radicals, antioxidants, and human disease: curiosity, cause, or consequence? The Lancet. 1994;344(8924):721–724. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92211-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mitscher LA, Telikepalli H, McGhee E, Shankel DM. Natural antimutagenic agents. Mutation Research . 1996;350(1):143–152. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(95)00099-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sala A, Del Carmen Recio M, Giner RM, et al. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties of Helichrysum italicum. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2002;54(3):365–371. doi: 10.1211/0022357021778600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Liu X, Dong M, Chen X, Jiang M, Lv X, Yan G. Antioxidant activity and phenolics of an endophytic Xylaria sp. from Ginkgo biloba. Food Chemistry. 2007;105(2):548–554. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Harper JK, Arif AM, Ford EJ, et al. Pestacin: a 1,3-dihydro isobenzofuran from Pestalotiopsis microspora possessing antioxidant and antimycotic activities. Tetrahedron. 2003;59(14):2471–2476. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Strobel G, Ford E, Worapong J, et al. Isopestacin, an isobenzofuranone from Pestalotiopsis microspora, possessing antifungal and antioxidant activities. Phytochemistry. 2002;60(2):179–183. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00062-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kardošová A, Machová E. Antioxidant activity of medicinal plant polysaccharides. Fitoterapia. 2006;77(5):367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Luo D, Fang B. Structural identification of ginseng polysaccharides and testing of their antioxidant activities. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2008;72(3):376–381. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sun C, Wang J-W, Fang L, Gao X-D, Tan R-X. Free radical scavenging and antioxidant activities of EPS2, an exopolysaccharide produced by a marine filamentous fungus Keissleriella sp. YS 4108. Life Sciences. 2004;75(9):1063–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Yu R, Yang W, Song L, Yan C, Zhang Z, Zhao Y. Structural characterization and antioxidant activity of a polysaccharide from the fruiting bodies of cultured Cordyceps militaris. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2007;70(4):430–436. [Google Scholar]

- 110.Liu J, Luo J, Ye H, Sun Y, Lu Z, Zeng X. Production, characterization and antioxidant activities in vitro of exopolysaccharides from endophytic bacterium Paenibacillus polymyxa EJS-3. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2009;78(2):275–281. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Song YC, Huang WY, Sun C, Wang FW, Tan RX. Characterization of graphislactone A as the antioxidant and free radical-scavenging substance from the culture of Cephalosporium sp. IFB-E001, an endophytic fungus in Trachelospermum jasminoides. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2005;28(3):506–509. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Borges KB, Borges WDS, Pupo MT, Bonato PS. Endophytic fungi as models for the stereoselective biotransformation of thioridazine. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2007;77(3):669–674. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Doble M, Kruthiventi AK, Gaikar VG, editors. Biotransformations and Bioprocesses. New York, NY, USA: Marcel Dekker; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Suresh B, Ritu T, Ravishankar GA. Food Biotechnology. 2nd edition. New York, NY, USA: Taylor and Francis; 2006. Biotransformations as applicable to food industries; pp. 1655–1690. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Borges KB, Borges WDS, Pupo MT, Bonato PS. Stereoselective analysis of thioridazine-2-sulfoxide and thioridazine-5-sulfoxide: an investigation of rac-thioridazine biotransformation by some endophytic fungi. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 2008;46(5):945–952. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Aleu J, Collado IG. Biotransformations by Botrytis species. Journal of Molecular Catalysis. 2001;13(4–6):77–93. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Longo MA, Sanromán MA. Production of food aroma compounds: microbial and enzymatic methodologies. Food Technology and Biotechnology. 2006;44(3):335–353. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Figueiredo AC, Almendra MJ, Barroso JG, Scheffer JJC. Biotransformation of monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes by cell suspension cultures of Achillea millefolium L. ssp. Millefolium. Biotechnology Letters. 1996;18(8):863–868. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Verza M, Arakawa NS, Lopes NP, et al. Biotransformation of a tetrahydrofuran lignan by the endophytic fungus Phomopsis sp. Journal of the Brazilian Chemical Society. 2009;20(1):195–200. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zikmundová M, Drandarov K, Bigler L, Hesse M, Werner C. Biotransformation of 2-benzoxazolinone and 2-hydroxy-1,4-benzoxazin-3-one by endophytic fungi isolated from Aphelandra tetragona. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2002;68(10):4863–4870. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.10.4863-4870.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Maróstica MR, Jr., Pastore GM. Production of R-(+)-α-terpineol by the biotransformation of limonene from orange essential oil, using cassava waste water as medium. Food Chemistry. 2007;101(1):345–350. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Miyazawa M, Kawazoe H, Hyakumachi M. Biotransformation of l-menthol by twelve isolates of soil-borne plant pathogenic fungi (Rhizoctonia solani) and classification of fungi. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology. 2003;78(6):620–625. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Farooq A, Tahara S, Choudhary MI, et al. Biotransformation of (-)-α-pinene by Botrytis cinerea. Zeitschrift fur Naturforschung C. 2002;57(3-4):303–306. doi: 10.1515/znc-2002-3-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Farooq A, Choudhary MI, Tahara S, Rahman AU, Başer KH, Demirci F. The microbial oxidation of (-)-β-pinene by Botrytis cinerea. Zeitschrift fur Naturforschung C. 2002;57(7-8):686–690. doi: 10.1515/znc-2002-7-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Zhang J, Zhang L, Wang X, et al. Microbial transformation of 10-deacetyl-7-epitaxol and 1β- hydroxybaccatin I by fungi from the inner bark of Taxus yunnanensis. Journal of Natural Products. 1998;61(4):497–500. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Shibuya H, Kitamura C, Maehara S, et al. Transformation of Cinchona alkaloids into 1-N-oxide derivatives by endophytic Xylaria sp. isolated from Cinchona pubescens. Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2003;51(1):71–74. doi: 10.1248/cpb.51.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Simanjuntak P, Prana TK, Wulandari D, Dharmawan A, Sumitro E, Hendriyanto MR. Chemical studies on a curcumin analogue produced by endophytic fungal transformation. Asian Journal of Applied Sciences. 2010;3:60–66. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Bastos DZL, Pimentel IC, de Jesus DA, de Oliveira BH. Biotransformation of betulinic and betulonic acids by fungi. Phytochemistry. 2007;68(6):834–839. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]