Abstract

Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis (Map) is the causative agent of johne's disease whose immunopathology mainly depends on cell mediated immuneresponse. Genome sequencing revealed various PPE (Proline-Proline-Glutamic acid) protein family of Map which are immunologically importance candidate genes In present study we have developed a bicistrionic construct pIR PPE/IFN containing a 34.9 kDa PPE protein (PPE 34.9) of Map along with a cytokine gene encoding murine gamma Interferon gene (IFNγ) and a monocistrionic construct pIR PPE using a mammalian vector system pIRES 6.1. The construct were transfected in HeLa cell line and expression were studied by Western blot as well as Immunefluroscent assay using recombinant sera. Further we have compared the immunereactivity of these two constructs in murine model by means of DTH study, LTT, NO assay and ELISA. DTH response was higher in pIR PPE/IFN than pIR PPE group of mice, similar finding also observed in case of LTT and NO production assay . ELISA titer of the pIR PPE/IFN was less than that with PPE only. These preliminary finding can revealed a CMI response of this PPE protein of Map and IFNγ having synergistic effect on this PPE protein to elicit a T cell based immunity in mice.

1. Introduction

Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosisis (MAP) is an intracellular pathogen, the causative organism of Johne's disease (paratuberculosis), a debilitating chronic enteritis in ruminants and has been implicated in Crohn's disease in humans characterised by hepatic granulomas in HIV-negative, nonimmunosuppressed patients [1]. This pathogen can multiply inside mononuclear phagocytes due to presence of various virulence determinants on their surface [2], and it is evident that cell-mediated immune response controls the resulting pathology.

The name PPE is derived from the motifs Pro-Pro-Glu, found in conserved domains near the N termini of these proteins having 180 amino acid sequences [3]. PPE proteins are thought to be expressed on the cell surface [4, 5] and have been found to be immunodominant antigens [6]. Some of the PPE proteins of Mycobacterium species have been reported to be potent T cell and or B cell antigens [7–14].

Although studies on various secretory proteins of mycobacterial species have shown that they are potential immunogens and can be used as subunit vaccine, using efficient immune adjuvants can enhance the performance of the DNA vaccine. Various cytokines especially IFNγ, IL-2, IL-6, IL-12, and IL-1 play a key role in immunity against mycobacterial infections [15] and have been shown to increase the protectivity while used for coimmunization with DNA vaccines. The essential task of IFNγ in the resistence of mice to mycobacterial infections has been make clear by reports that knockout of IFNγ gene from the mice cannot control or inhibit different mycobacterial infections [16]. Recently, a recombinant PPE protein, Map41, which has been reported as one of the IFN-γ-inducing antigens of MAP, also strongly induced IL-10 from macrophages obtained from infected calves [14].

Bicistronic vectors have been used to design DNA vaccine against HIV infection, which contained gp120 and GM-CSF gene [17], bicistronic DNA vaccine containing apical membrane antigen 1 and merozoite surface protein 4/5 can prime humoral and cellular immune responses and partially protect mice against virulent plasmodium chabaudi adami DS malaria [18], and a bicistronic woodchuck hepatitis virus core and gamma interferon DNA vaccine can protect from hepatitis [19]. Recently from our laboratory, Kadam et al. [20], have reported that coexpression of IFNγ with a 16.8 kDa gene of MAP can enhance immunogenicity of DNA vaccine using the same protein. In the present study, we have used a similar approach to clone a 34.9 kDa PPE (PPE34.9) antigen of MAP in the A frame of the bicistronic vector pIRES 6.1 having IFNγ gene in the frame B used by Kadam et al. [20]. Further, we have studied the coexpression of these two antigens in HeLa cell line. We have also preliminary attempted to elucidate the immunogenic effect of PPE 34.9 antigen of MAP on murine model and the role of IFNγ's adjuvant properties.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mycobacterial Strains

Solid and liquid cultures of MAP 316F were obtained from Central Diengenees Kunding Tieh Institute, Lelystad, the Netherlands and maintained at Biological Products Division of IVRI, Izatnagar, and later maintained at Gene Expression Laboratory, Division of Animal Biotechnology, IVRI, Izatnagar.

2.2. Plasmid Vectors and Host Strain Used

pTZ57R/T Cloning vector and host strain DH5α of E. coli were supplied by MBI Fermentas, Germany. Bicistronic vector pIRES 6.1 was supplied from Clontech, USA.

2.3. Laboratory Animals

Swiss albino mice and New Zealand white rabbits were obtained from Laboratory Animal Resource Section, IVRI, Izatnagar. Standard prescribed guidelines for care and use of laboratory animals were followed during the experimentation with these animals.

2.4. Culture and Growth of MAP

MAP organisms were grown on Middlebrook 7H10 agar enriched with 0.1% glycerol v/v and 10% OADC with additional supplementation of Mycobactin J (2 mg/L) and were maintained at 37°C.

2.5. Isolation of Genomic DNA Form MAP

The genomic DNA from MAP was isolated by following the published method [21].

2.6. Oligonucleotide Primers

A set of primers were designed for the specific amplification of the 1080 bp PPE34.9 gene of MAP based on the sequence information of MAP str.k10, complete genome Gene Bank Accession no. AE016958. Similarly, one set of primers was designed for the amplification of murine interferon gamma gene based on sequence information (Gene bank Accession no. NM_008337). The primers were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, USA. The nucleotide sequences of these primers were as follows (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of specific primers used for the present study.

| Primers | Oligonucleotide sequences |

|---|---|

| pIRES MPPPE F(Sense) |

5′GCC GCT AGC ATG TGG GTC CAG GCC GCC AC 3′-29 mers |

| pIRES MPPPE R(Anti sense) |

5′GCC GAA TTC TTA CTC GGT TCC AGC GTT GC 3′-29 mers |

| IFN F(Sense) |

5′GCC TCT AGA ATG AAC GCT ACA CAC TGC 3′-27 mers |

| IFN F(Anti sense) |

5′CCG CGG CCG CTC AGC AGC GAC TCC TTT T 3′-28 mers |

2.7. Polymerase Chain Reaction and Amplification of PPE34.9 Gene Fragment

Specific amplification of the PPE gene from the genomic DNA of M. a. paratuberculosis was carried out using the above-mentioned primers pIRES MAP PPE F and pIRES MAP PPE R. The PCR was carried out in 25 μL reaction volume using 1 μL of genomic DNA (10 ng) as template, 2.5 μL of PCR buffer, 1 μL of MgCl2 (1.5 mM), 1 μL (25 μM) of each primers, 1 μL of dNTP mix (200 μM of each dNTP), and 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase. The volume was made up to 25 μL by adding DNase-free water. The thermal cycling steps were carried out in PTC-200 thermocycler MJ Research Inc., USA with initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min followed by 30 cycles with denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 55.0°C for 1 min, extension at 72°C for 30 seconds, and final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Size of the amplified product was confirmed by using DNA molecular weight marker in a 1% agarose gel and quantified by spectrophotometric analysis.

2.8. Cloning of PPE34.9 Gene of MAP in pTZ57R/T Cloning Vector

2 μL (100 ng) of eluted PCR product, 1 μL of pTZ57R/T (55 ng), 2 μL of 5X ligation buffer, 1 μL of T4 DNA ligase (5 units) were mixed in a sterile microcentrifuge tube and the volume was made up to 10 μL with nuclease free water. The ligation mixture was kept at 22°C overnight and stored at −20°C. Competent E. coli DH5α cells were prepared and transformed with 10 μL of ligation mixture as stated above. The transformed cells were spread on LB agar plate containing ampicillin (100 μg/mL), X-GAL (25 μg/mL) and IPTG (25 μg/mL). Appropriate positive and negative controls were processed simultaneously. Plates were incubated at 37°C overnight and later stored at 4°C. Ten white colonies were picked up and grown in LB broth containing ampicillin and incubated at 37°C overnight in a shaker incubator at 180 rpm. Plasmid DNA was extracted by miniprep plasmid isolation method [22]. Identification of positive colonies was done by Colony PCR and subsequently confirmed by RE analysis and designated as pTZ PPE.

2.9. Cloning of PPE Gene of MAP in a Mammalian Bicistronic Expression Vector pIRES and Plasmid Construct pIR IFN

The insert from the positive clone pTZ PPE (containing the appropriate restriction sites NheI and EcoRI specific for frame A of pIRES vector) was released by digesting with the enzymes Nhe I and EcoRI. The digested product was then ligated in the frame A after digestion of the vector with Nhe I and EcoRI to prepare monocistronic construct pIR PPE. The ligation mixture was transformed in E. coli competent DH5α cells. Further, to prepare bicistronic construct pIR PPE/IFN, pIR IFN [20] was used and same strategy was adapted to insert the PPE 34.9 in the frame A.

2.10. Preparation of Transfection Grade Plasmid

Large scale purification of the plasmid constructs pIR PPE and pIR PPE/IFN was done using endotoxin-free QIAGEN mega kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, California).

2.11. Transfection of Plasmid Constructs in HeLa Cell line

The purified recombinant plasmids pIR PPE and pIR PPE/IFN were transfected to 60–70% confluent HeLa cells using SuperFect transfection reagent kit, following manufacturer's instructions (QIAGEN, Germany). Briefly, HeLa cell monolayer was subcultured and the cells were seeded in 25 cm2 tissue culture flask. When 60–70% monolayer was achieved, the cells were used for transfection. 5 μg of each DNA in 20 μL TE (pH 7.5) was diluted separately in optiMEM. Then 30 μL of superfect transfection reagent was added to the DNA solution. Afterwards, growth medium was aspirated from the dish and cells were washed with two mL DMEM (without serum and antibiotic). Then, 0.8 mL of the same DMEM were added to the reaction tube containing the transfection complexes and mixed properly. The mixtures thus prepared were layered separately over the cells and incubated for 6 hrs at 37°C followed by addition of DMEM with 10% FCS, and incubation was continued in a humidified CO2 incubator. Cells transfected with the respective plasmid constructs were harvested after 72 hrs of incubation by adding about 80 μL of 2X SDS-PAGE loading buffer, and the expressed proteins were resolved on SDSPAGE and western blotting using hyperimmune sera raised in rabbit against recombinant PPE 34.9 protein (1 : 200 in PBS).

2.12. RT-PCR (Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction) for Conformation of Expression of IFN

One mL of trizol was layered on the transfected monolayer and the cells were lysed. Total RNA was isolated from the cells and amplified by RT-PCR. The amplified product was checked on 1.5% agarose. One mL trizol was added on the transfected monolayer and homogenized by passing the lysate 10 times through a sterile 20 G needle fitted to a syringe and transferred to a sterile 1.5 mL eppendorf. Further, the sample was kept at room temperature for five minutes. 200 μL of chloroform was added to the sample and mixed by vortexing. It was allowed to stand at room temperature for 10 minutes. The sample was then centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 20 minutes. The aqueous phase was collected in a separate vial to which 500 μL of isopropanol was added, mixed gently, and kept at room temperature. RNA pallet was washed with 500 μL 70% ethanol and dissolved in nuclease-free water. The yield of total RNA was determined spectrophotometrically using the formula

| (1) |

RT-PCR was carried out using RT PCR kit (MBI Fermentas, Germany). In a sterile microfuge tube, 2 μg of total RNA from pIR PPE/IFN were carried out to which 1 μL of random hexamer primer was added and incubated at 70°C for 5 min. Then, mixture, 1 μL RNase inhibitor, 2 μL of DNTP, and 4 μL of 5x RT buffer were added and tube was incubated at 37°C for 5 min. Thereafter, 1 μL of m MLV reverse transcriptase was added and the volume was made up to 20 μL by adding nuclease free water. The sample was incubated at 42°C for 1 hr, followed by incubation at 72°C for 10 min. The cDNA was stored at −20°C, until used. Amplification of IFNγ specific fragment from the cDNA preparation was prepared containing 4 μL of the cDNA sample, 2.5 μL of 10x PCR buffer, 200 μM of each Dntp, and 50 pMol each primers IFNpIR F and IFNpIR R. IFNγ amplification mixture was subjected to 30 cycles of denaturation (94°C, 1 min), annealing (55°C, 45 sec), and extension (72°C, 1 min) with a further final cycle for primer extension (72°C, 5 min).

2.13. Indirect Immunofluorescence Assay (IFA)

HeLa cells were seeded in 24 well plates and when a 60–70% confluent monolayer was achieved, two wells each were transfected with pIR PPE, pIR PPE/IFN, and pIRES (mock) plasmid. After incubation for 72 hr the medium was aspirated from all the wells, and the cells were permeabilized by adding 250 μL of 80% acetone for 30 min. Then, acetone was aspirated and the plate was dried at RT for 1 hr. Blocking was done using 1% BSA for 2 h at 37°C. Primary antibody (hyperimmune sera) was added at 1 : 50 dilution and kept for one hr at 37°C. This was followed by three gentle washes with PBS. FITC-labeled antirabbit conjugate was added at 1 : 200 dilution and kept for 1 hr at 37°C followed by washing with PBS and mounted in 50% PBS-glycerol. Cells were examined under fluorescent microscope.

2.14. Immunization of Animals with Plasmid Constructs

Swiss albino mice supplied by Laboratory Animal Section, IVRI, Izatnagar were maintained on ration comprising wheat dalia 62%, maize 30%, wheat bran 7%, salt 1%, and mineral mixture 25 ppm with 5 mL milk per mouse. The animals were divided into four groups, namely, A, B, C, and D each containing ten mice. They were vaccinated with the purified recombinant plasmid as shown in the Table 2.

Table 2.

Mice Immunization schedules.

| S. no. |

Mice group |

Plasmid construct used |

First dose (0 day) |

Booster dose (35th day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | TE buffer control | 100 μg | 100 μg |

| 2 | B | pIRES mock control | 100 μg | 100 μg |

| 3 | C | pIRESPPE | 100 μg | 100 μg |

| 4 | D | pIRESPPE /IFN | 100 μg | 100 μg |

Mice (three numbers) from each group were bled on the 21st and the 42nd days for serum separation which were stored at −20°C and used in the determination of antibody titres by ELISA.

2.15. Collection of Macrophages and Splenocytes from Plasmid-Immunized mice

On the 42nd day after immunization of mice, four mice from each group were selected randomly. About 5 mL of sterile RPMI 1640 medium were injected into the peritoneal cavity of each mouse, gently massaged, and the mice were left in the cage for 5 min. Then, the mice were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation, and the peritoneal fluid was aspirated. The macrophages in the aspirated fluid were collected by centrifugation and resuspension of the obtained pellet in RPMI 1640 medium and subsequently used for nitric oxide (NO) estimation. After aspiration of peritoneal fluid, abdominal cavity was cut open. Spleens were harvested from sacrificed mice and made into a single cell suspension. The cells suspended in RPMI-1640 were layered over Ficoll-Paque PLUS, and mononuclear splenocytes were isolated by density gradient centrifugation at 1350 × g for 30 min. Splenocytes thus obtained were used for LTT and RNA isolation.

2.16. Measurement of DTH Reaction

Six mice from each group were selected for DTH study. On the 42nd day after first immunization. All the mice were injected intradermally with 10 μg of johnin in right hind foot pad and 10 μg of purified PPE 34.9 recombinant protein in the left hind foot pad. The results of the local skin reactions (DTH) were observed after 48 h by measuring the two transverse diameters of erythema using Vernier calipers with a minimum measurable increment of 0.01 mm. Data was statistically analyzed using Students' t-test at a significant level of P < .05.

2.17. Lymphocyte Transformation Test (LTT)

The mononuclear splenocytes (5 × 105 cells per well) from four mice were placed in 96 well plates (Nunc, Denmark) in complete RPMI-1640 (phenol red free) medium containing 10% heat-inactivated foetal calf serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U of penicillin, and 100 mg streptomycin per ml. Respective Ni NTA column-purified recombinant PPE 34.9 [23] and ConA (positive control) were added at the final concentration of 40 μg/mL and 10 μg/ml, respectively. RPMI was used as the negative control. The total volume per well was 200 μL. The plates were kept in a humidified CO2 incubator at 37°C for 72 h. At the end of the incubation, 20 μL of the yellow tetrazolium salt MTT (5 mg/mL) were added and incubated at 37°C for 4 h. In the presence of living cells, MTT is transformed to purple formazan [24]. Subsequently, 100 μL of 0.04 N HCl in isopropanol were added and allowed to react for 30 min to stop the colour development reaction and dissolve the formazan crystals. The absorbance (OD) of the samples was measured in an ELISA reader at 570 nm (and 650 nm as reference) wavelength. Assays were conducted in triplicates, and the results expressed as Mean ± SE. Stimulation index (SI) was calculated using the formula SI = OD of stimulated culture ÷ OD of unstimulated culture. SI value of >1.2 (i.e., 33% more than the control) was considered for lymphocyte proliferation. Data was analysed for significance between mock pIR and pIR PPE as well as pIR PPE and pIR PPE/IFN constructs by Student's t-test, and differences with P < .05 were considered within the level of significant.

2.18. NO Production Assay

The RPMI 1640 complete medium was supplemented with 5 mM of L-arginine for this assay. 100 μL of the cell suspension containing 2 × 105 peritoneal macrophages from four mice from each group were plated in triplicate in 96 well plates. Respective antigen Ni NTA column-purified recombinant PPE 34.9 [23] and LPS (positive control) in RPMI 1640 medium (100 μL) were added at the final concentration of 40 μg/mL and 2 μg/mL, respectively. RPMI was used as the negative control. The total volume per well was 200 μL. The plates were incubated at 37°C in a humidified CO2 (5%) incubator for 48h. Supernatants were collected from all the wells and stored at −20°C until NO estimation. For NO estimation NaNO2 (sodium nitrite) in different concentrations was used as standard. In a 96-well ELISA plate to 50 μl of the cell culture supernatant or standard, 60 μL of Griess reagent (1% sulfanilamide in 1.2 N HCl) (Sigma) was added, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 30 min, A550 reading was taken on a microplate ELISA reader. By using the standard curve (NaNO2 concentration versus A550) the NO levels in the samples were estimated. Data was analysed by Student's t-test, and differences with P < .05 were considered significant.

2.19. Characterization of PPE Specific Antibodies in Mice Groups Immunized with Plasmid Constructs by ELISA

The optimum concentration of Ni NTA column-purified recombinant PPE 34.9 [23] antigen and conjugate were determined using block titration as described by Engwal and Pearlman [25]. The wells of ELISA plates (Nunc, Denmark) were coated with 200 ng/well of antigen diluted in carbonate bicarbonate buffer, and the plates were incubated at 4°C overnight. The plates were washed thrice with PBS-Tween 20 (PBS-T) and blocked with 5% skim milk powder in PBS-T for 2 h at 37°C. Then, 1 : 200 dilution of serum in 100μL volume of PBS-T were added in duplicate and incubated at 37°C for one hour. The plates were washed thrice with PBS-T for 3 min at each wash. Conjugate antimouse IgG HRPO at dilution of 1 : 10,000 in 100 μL volume was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for 1hr at 37°C. The plates were then washed three times with PBS-T, and colour was developed with 100 μL of 10 mg/mL OPD with 10 μL of 30% H2O2 in substrate buffer. After sufficient colour development, the reaction was stopped by the addition of 50 μL 1N H2SO4, and the plates were read at 490 nm in an ELISA reader (Tecan, Austria).

3. Results

3.1. Construction and Characterization of Plasmids pIR PPE and pIR PPE/IFN

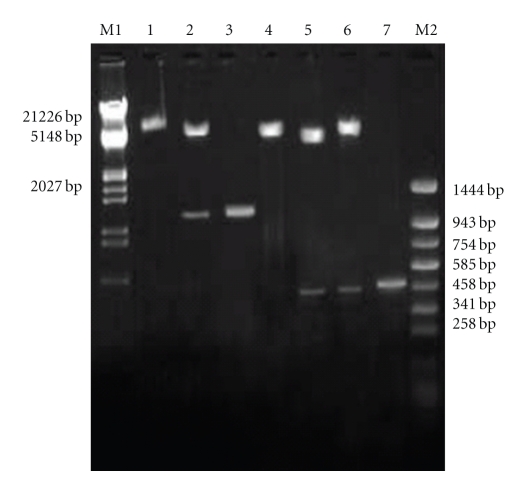

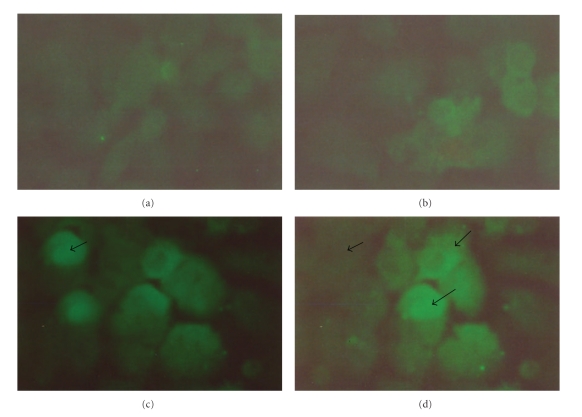

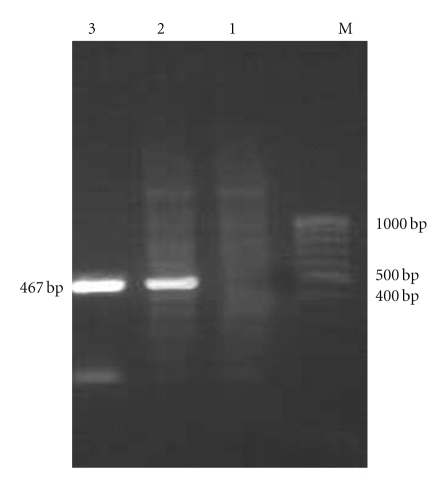

The bicistronic constructs were generated after cloning PPE34.9 gene fragment from Nhe I and Eco RI digested PCR product into frame A of Nhe I and Eco RI digested plasmid vector and Xba I- Not I digested IFNγ into frame B of the same vector. The positive colonies from the construct was identified by obtaining desired size products using colony PCR and subsequently confirmed by the release of identical size inserts on RE analysis (Figure 1). The plasmid constructs (monocistronic and bicistronic) were transfected into 60–70% confluent HeLa cell line, and the expressed PPE34.9 protein was detected from 72-hour posttransfected cell lysate in western blot using polyclonal serum raised in rabbit against recombinant PPE34.9. No such band was observed in cell lysate transfected with mock plasmid (Figure 2). The 72-hour posttransfected HeLa cells with plasmid constructs pIR PPE and pIR PPE/IFN on IFA using FITC-labeled conjugate exhibited fluorescence under fluorescent microscope, indicating the expression of the PPE34.9 protein (Figures 3(a), 3(b), 3(c), and 3(d)).The monoclonal antibodies against murine IFNγ could bind with HeLa cell expressed IFN protein to reconfirm IFNγ expression from the construct pIRPPE/IFN, RT-PCR was done for the cDNA obtained from total RNA of a 72-hour posttransfected HeLa cell lysate using specific primers of murine IFNγ. At 55°C, annealing temperature gave the amplified product of 467 bp (Figure 4).

Figure 1.

Agarose gel electrophoresis (1%) of the cloned fragment of the gene encoding PPE protein in pIRES IFN PPE mammalian vector. Lane M1: DNA molecular weight marker Lamda DNA/EcoRI/Hind III. Lane 1: pIRES IFN PPE linearised with EcoRI. Lane 2: released insert of 1080 bp after NheI and EcoRI digestion of recombinant pIRES IFN PPE recombinant plasmid DNA. Lane 3: PCR amplified fragment encoding PPE protein of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis. Lane 4: pIR IFN linearised with Xba I. Lane 5: release IFN fragment (467 bp) by digestion with Xba I and Not I from pIR IFN vector DNA. Lane 6: release IFN fragment (467 bp) by digestion with Xba I and Not I from pIR IFN PPE vector DNA. Lane 7: PCR amplified fragment of IFN (467 bp). Lane M2: DNA molecular weight marker pUC18/Sau3AI-pUC18/TaqI digest.

Figure 2.

Western blot assay of 72-hour culture of HeLa cell transfected with pIRPPE and pIRPPE/IFN showing expressed 34.9 kDa PPE protein. Lane M: prestained protein molecular weight marker. Lane 1: whole cell lysate of HeLa cell transfected with pIRES (mock control). Lane 2: whole cell lysate of HeLa cell transfected with pIRES PPE. Lane 3: whole cell lysate of HeLa cell transfected with pIRES PPE/IFN.

Figure 3.

(a) Healthy HeLa cells (untransfected). (b) HeLa cells transfected with pIRES mock control. (c) HeLa cells transfected with pIRES PPE vector construct showing expression of PPE protein using o polyclonal sera raised in rabbit against PPE 34.9 react with FITC-labeled antirabbit conjugate. (d) HeLa cells transfected with pIRES PPE/IFN vector construct showing expression of PPE protein using o polyclonal sera raised in rabbit against PPE 34.9 react with FITC-labeled antirabbit conjugate.

Figure 4.

Agarose gel electrophoresis (1.5%) showing RT-PCR based expression of IFNγ ORF in pIR PPE IFN transfected HeLa cells. Lane M: prestained protein molecular weight marker (100 bp ladder). Lane 1: negative control mock plasmid transfected HeLa cells. Lane 2: IFNγ encoding gene from pIR PPE IFN transfected HeLa cells with super natantγ. Lane 3: positive control (IFNγ) encoding gene from ConA induced mice splenocytes.

3.2. Induction of DTH Response

DTH response was measured with Vernier Calipers 72 hrs after injection of PPE34.9 protein in the foot pad of Plasmid-immunized groups of mice. Skin reactions to recombinant PPE34.9 protein was studied. Both the control groups showed no significant reaction to antigen. Mice group immunized with pIR PPE and pIR PPE/IFN evoked visible skin reactions in the form of necrosis and erythema. However, more significant (3.115 ± 0.005) erythematous lesions were observed in mice immunized with pIR PPE/IFN in comparison to pIR PPE-immunized groups (2.516 ± 0.132). Whereas, mice immunized with plasmid pIRES (mock) showed no significant swelling when compared to the injection of PBS (Table 3). Statistical analysis with Student's t-test showed significant difference (P < .05) between pIR PPE/IFN and pIR PPE alone.

Table 3.

DTH responses in mice immunized with plasmid constructs expressed as mean differences (mm) upon recall with 10 microgram of PPE34.9.

| Groups | PBS | PPE 34.9 |

|---|---|---|

| Group A (TE buffer as control) | 0.082 ± 0.001 | 0.235 ± 0.018 |

| Group B pIRES (mock) | 0.082 ± 0.0007 | 0.111 ± 0.011 |

| Group C pIRES PPE | 0.211 ± 0.007 | 2.516 ± 0.132 |

| Group D pIRES PPE | 0.215 ± 0.0104 | 3.115 ± 0.005 |

3.3. LTT-Based In Vitro Lymphocyte Proliferation Test

The purified recombinant PPE34.9 protein stimulated a significant proliferation of mononuclear splenocytes from mice groups immunized with constructs pIR PPE and pIR PPE/IFN. Higher proliferation was obtained with construct pIR PPE/IFN (1.38 ± 0.079) followed by group pIR PPE (1.21 ± 0.076) upon stimulation with purified PPE34.9 protein. (Table 4). Statistical analysis with student's t-test showed significant difference (P < .05) between pIR (mock) and pIR PPE as well as pIR PPE and pIR PPE/IFN groups.

Table 4.

Lymphocyte transformation test for mice groups immunized with Plasmid constructs (SI = Mean ± SEM).

| Groups | ConA | PPE protein |

|---|---|---|

| A (TE buffer control) | 1.03 ± 0.05 | 0.96 ± 0.042 |

| B (pIRES mock control) | 1.04 ± 0116 | 0.97 ± 0.031 |

| C (pIRESPPE) | 1.3 ± 0.101 | 1.21 ± 0.076 |

| D (pIRESPPE /IFN) | 1.41± 0.17 | 1.38 ± 0.079 |

3.4. NO Production Assay

Peritoneal macrophages collected from various mice groups were stimulated with the respective antigens to measure the amount of nitric oxide produced by the cells. The quantity of NO produced was estimated by comparing with known standards of sodium nitrite. LPS induced significant production of NO in all the groups. Among the immunized groups, NO production was found highest in group pIR PPE/IFN (Mean ± SEM = 38.62 ± 1.02 μm/2 × 105 cells) followed by group pIR PPE (Mean ± SEM = 26.19 ± 0.53 μm/2 × 105 cells) upon stimulation with recombinant PPE34.9 protein. (Table 5). Statistical analysis with student's t-test showed significant difference (P < .05) between pIR (mock) and pIR PPE as well as pIR PPE and pIR PPE/IFN groups.

Table 5.

Nitric oxide production assay of peritoneal macrophages from mice groups immunized with Plasmid constructs (μm of NO/2 × 105 cells = Mean ± SEM).

| Groups | LPS | PPE protein |

|---|---|---|

| A (TE buffer control) | 29.32 ± 0.5042 | 7.85 ± 0.2933 |

| B (pIRES mock control) | 30.77 ± 0.6617 | 7.29 ± 0.3199 |

| C (pIRESPPE) | 33.43 ± 1.9381 | 26.19 ± 0.535 |

| D (pIRESPPE /IFN) | 40.89 ± 2.3452 | 38.62 ± 1.020 |

3.5. Detection of Immune Response Induced by Various Plasmids Constructs in Mice by ELISA

To evaluate the humoral immune response induced by plasmid constructs in mice groups, on the 21st day and the 42nd day postimmunization antibody titres were determined by indirect ELISA. Antibodies were detected in all the plasmid constructs immunized groups of mice (OD490 > 0.3 in the serum dilution range of 1 : 200). Whereas, insignificant titres were observed in control groups (Table 6).

Table 6.

ELISA titres of plasmid construct-injected mice groups (OD490 = Mean ± SEM).

| Groups | 21st day | 42nd day |

|---|---|---|

| Blank | 0.031 ± 0.0035 | 0.044 ± 0.0034 |

| A (TE buffer control) | 0.131 ± 0.0076 | 0.136 ± 0.012 |

| B (pIRES mock control) | 0.142 ± 0.0371 | 0.156 ± 0.012 |

| C (pIRESPPE) | 0.312 ± 0.0204 | 0.322 ± 0.030 |

| D (pIRESPPE /IFN) | 0.263 ± 0.018 | 0.283 ± 0.021 |

4. Discussion

Presently, chemotherapy is unrewarding and economically not feasible to control the diseases. Effective control programmes for the disease are hampered due to lack of specific diagnostic tests to detect infection in the early stages of disease. Further the currently available immunodiagnostic tests have limited sensitivity [26] and specificity [27].

Conventional live attenuated vaccines are not completely protective [28, 29]. Studies have shown that CMI develops in early stages for clearing infection [30] whereas high serum antibody concentration is often seen in advanced clinical cases [31]. The cell-mediated immunity plays a pivotal role to control the spread of organisms within the host body [32]. DNA vaccines may open new horizons for effective vaccination against paratuberculosis as strong CMI responses including CTL and Th1 type cytokines are induced [20].

Expressions of T cell antigens in prokaryotic vector have failed to induce CTL and cytokine response. However, expression of T cell antigen in a mammalian vector for eliciting CD4+ T cell response and CD8+ cytotoxic T cell response to generate immunity have been reported in a number of animal models [33–36]. Cytokines also (mainly IFNγ, TNFα, IL10 etc.) play a major role in the protective immune response against mycobacterial diseases [14, 32]. Coexpression of T cell antigen with costimulatory molecules in a bicistronic eukaryotic system made the DNA vaccine more effective [17–20]. Moreover, expression of two T cell antigens in eukaryotic bicistronic system may also be useful for enhancing protective immunity.

After the completion of the genome sequencing of MAP, the PPE protein family has been widely assumed to represent immunologically important antigens of the mycobacterial species. The present work envisaged keeping in view the role of a PPE antigen and the concept of bicistronic DNA constructs using an immunostimulatory molecule IFNγ is likely to potentiate immune response in mice. The use of cytokines as adjuvant is known to enhance immune responses when they were administered during the development of immune response against a particular antigen [37, 38]. IFNγ is the most extensively studied cytokine in mycobacterial infections. It is the defining cytokine of Th1 subset and activates macrophages for microbicidal activity. It induces IL12, which causes Th cells to differentiate into Th1 subset [39].

In the present study, the gene fragment encoding PPE34.9 protein was cloned into the frame A of the bicistronic vector pIRES6.1 containing IFNγ gene in frame B and also a monocistronic plasmid construct pIR PPE was made. The constructs were designated as pIR PPE/IFN and pIR PPE, respectively. Bicistronic vector pIRES6.1 contained immediate early CMV promoter for simultaneous expression of the two genes downstream to it as active protein. Expression of the PPE34.9 and IFNγ. (17 kDa) proteins was confirmed by western blot and immunofluorescence assay in 72-hour posttransfected HeLa cell lysates using polyclonal sera. Size of mouse IFNγ. gene is 1208 bp in length but coding sequence is 467 bp, which was used for IFNγ. ORF expression. The results were in agreement with the eukaryotic bicistronic expression of 16.8 kDa antigen of MAP and murine IFNγ.in a bicistronic vector [20], a glycoprotein C of pseudorabies virus [40] and an apical membrane antigen and merozoite surface protein of Plasmodium chabaudi DS malaria [18].

In the present study, we have cloned and coexpressed a 34.9 kDa protein-encoding PPE gene family antigen with IFNγ gene in HeLa cell line. Further, we have studied the immune responses of these plasmid constructs in mice. Elucidation of DTH response against recombinant P35 proteins and 16.8 kDa proteins of MAP has been studied by and Basagoudanavar et al. [41] and Kadam et al. [20], respectively. DTH-based immune response is an indicator of T-cell-based immunity. We have already elucidated the DTH response of purified recombinant PPE 34.9 proteinin mice [23]. In the present study we have compare the effect of IFN as pIR PPE/IFN construct on PPE 34.9 as pIR PPE construct, which showed that a significant higher immune response of the first construct on the second one indicate the role of IFNγ to elicit a T cell based immune response.

Cell proliferation as a test has been used to assess DNA vaccines against mycobacterial infections [20, 41]. In the present study, mononuclear splenocytes from mice group immunized with pIR PPE/IFN showed higher cell proliferation than pIR PPE, which may indicate the effect of IFNγ. IL2 is known as the cytokine for cell proliferation, but IFNγ indirectly induces cell proliferation by activating macrophages and increasing antigen presentation which induces IL2 receptors on T cell surface, thereby inducing cell proliferation. The results were in consensus as found by other workers who used cytokines as immunoadjuvant in bicistronic DNA vaccine. Chow et al. [42] have reported increased cell proliferation in group that received hepatitis B virus surface protein and IL2 as bicistronic DNA vaccine. Barouch et al. [17] found twofold augmentation of cell proliferation in bicistronic group which coexpressed gp120 gene of HIV and GMCSF than in monocistronic gp120 immunized group. Kadam et al. [20], also found that bicistronic vector expressing a 16.8 kDa protein of MAP along with IFNγ gene induce higher proliferative response than the protein alone.

It is known that RNI r nitrogen intermediates), especially nitric oxide (NO), are most effective in direct killing of mycobacteria [15]. An increased production of NO-induced vaccine candidate genes may be one of the important causes of effective immune response against mycobacterial infection. As in our present study, NO production from cells of pIR PPE/IFN group was comparatively higher than PPE34.9 alone, it may again indicate the role of IFNγ in the induction/stimulation of macrophages to release RNI (NO). Recombinant protein PPE 34.9 was purified using single-step Nickel-NTA (pQE 30 UA containing His tag vector was used) affinity column chromatography [23], chance of LPS/endotoxin contamination is negligible. The results were in consensus as found by other workers who reported that it plays an important role in release of NO from monocytes [20, 43].

ELISA adopted to study the humoral immune response following DNA vaccination in mice for 22kDa antigen of M. bovis [44] and MPT64, Ag85B, and ESAT-6 [45] antigens of M. tuberculosis showed significant increase in log titre of circulating antibodies. In the present study, antibody titer of the construct pIR PPE/IFN was less than that with PPE34.9 only. It may be possible that here IFN down regulating the IgG mediate humoral immunity induced by PPE34.9 protein which needs to be further confirmed in large number of animals. This result may be correlated to the groups who find that codelivery of IFN-gamma or IL-4 encoding EG95 protein of Echinococcus granulosus, the causative agent of hydatid appeared to reduce the ability of the DNA vaccine to prime an IgG antibody response demonstrated the efficacy of the codelivery of cytokines to modulate immune responses generated in a DNA prime-protein boost strategy [46].

Overall, the preliminary findings possibly revealed that the PPE34.9 antigen of MAP may be a T-cell-based immunogen. This is in agreement with the studies reported on PE antigen of M. avium by Parra et al. [47], antigen induced both cell-mediated [48] and humoral immune responses [49] which again was in corroboration with the earlier works.

Immune adjuvants plays an important role to enhance the protective efficacy of DNA vaccines [50]. IFNγ is a potent activator of macrophages and is the key cytokine in Th1-type immune response in paratuberculosis infection produced by both CD4+ and CD8+ cells [20, 51]. Hence for the development of an effective measure against paratuberculosis, it is necessary to apply those strategies that should enhance the T cell mediate response. From our preliminary observations, we have also noticed that the monocistronic construct pIR PPE elicited a comparatively milder CMI response than pIR PPE/IFN. This may revealed that the presence of IFNγ synergized the T cell response of PPE34.9 protein.

These preliminary observations need further confirmation like in vitro study of the Th1 cytokine mediate response of the PPE34.9 and challenge studies in experimental as well as natural hosts for the development of an effective bicistronic DNA vaccine against paratuberculosis infection.

Acknowledgment

The authors are thankful to the Director of IVRI, Izatnagar for providing the necessary facilities to conduct the present study.

Abbreviations

- OADC:

Oleic acid dextrose catalase

- RPMI:

Roswell Park Memorial Institute

- DMEM:

Dulbecco's modified eagle medium

- FCS:

Fetal calf serum

- rpm:

Revolutions per minute

- DTH:

Delayed type hypersensitivity

- MTT:

4,5-dimethyl thiazol-2-4 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide

- NO:

Nitric oxide

- ELISA:

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

- RE:

Restriction enzyme.

References

- 1.Toyoda M, Yokomori H, Kaneko F, et al. Hepatic granulomas as primary presentation of Mycobacterium avium infection in an HIV-negative, nonimmunosuppressed patient. Clinical Journal of Gastroenterology. 2009;2(6):431–437. doi: 10.1007/s12328-009-0117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li YJ, Danelishvili L, Wagner D, Petrofsky M, Bermudez LE. Identification of virulence determinants of Mycobacterium avium that impact on the ability to resist host killing mechanisms. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2010;59(1):8–16. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.012864-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gey Van Pittius NC, Sampson SL, Lee H, Kim Y, Van Helden PD, Warren RM. Evolution and expansion of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis PE and PPE multigene families and their association with the duplication of the ESAT-6 (esx) gene cluster regions. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2006;6, article 95 doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-6-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brennan MJ, Delogu G, Chen Y, et al. Evidence that mycobacterial PE_PGRS proteins are cell surface constituents that influence interactions with other cells. Infection and Immunity. 2001;69(12):7326–7333. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.12.7326-7333.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delogu G, Pusceddu C, Bua A, Fadda G, Brennan MJ, Zanetti S. Rv1818c-encoded PE_PGRS protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is surface exposed and influences bacterial cell structure. Molecular Microbiology. 2004;52(3):725–733. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choudhary RK, Mukhopadhyay S, Chakhaiyar P, et al. PPE Antigen Rv2430c of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Induces a Strong B-Cell Response. Infection and Immunity. 2003;71(11):6338–6343. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.11.6338-6343.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okkels LM, Brock I, Follmann F, et al. PPPE protein (Rv3873) from DNA segment RD1 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: strong recognition of both specific T-cell epitopes and epitopes conserved within the PPE family. Infection and Immunity. 2003;71(11):6116–6123. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.11.6116-6123.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huntley JF, Stabel JR, Paustian ML, Reinhardt TA, Bannantine JP. Expression library immunization confers protection against Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis infection. Infection and Immunity. 2005;73(10):6877–6884. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6877-6884.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marri PR, Bannantine JP, Golding GB. Comparative genomics of metabolic pathways in Mycobacterium species: gene duplication, gene decay and lateral gene transfer. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 2006;30(6):906–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00041.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newton V, Mc Kenna SL, De Buck J. Presence of PPE proteins in Mycobacterium avium subsp. Paratuberculosis isolates and their immunogenecity in cattle. Veterinary Microbiology. 2009;135:394–400. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.09.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bertholet S, Ireton GC, Kahn M, et al. Identification of human T cell antigens for the development of vaccines against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Journal of Immunology. 2008;181(11):7948–7957. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.7948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nair S, Ramaswamy PA, Ghosh S, et al. The PPE18 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis interacts with TLR2 and activates IL-10 induction in macrophage. Journal of Immunology. 2009;183(10):6269–6281. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldstone RM, Goonesekera SD, Bloom BR, Sampson SL. The transcriptional regulator Rv0485 modulates the expression of a pe and ppe gene pair and is required for Mycobacterium tuberculosis virulence. Infection and Immunity. 2009;77(10):4654–4667. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01495-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagata R, Kawaji S, Minakawa Y, Wang X, Yanaka T, Mori Y. A specific induction of interleukin-10 by the Map41 recombinant PPE antigen of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis. Veterinary Immunology and Immunopathology. 2010;135(1-2):71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mullerad J, Hovav AH, Nahary R, Fishman Y, Bercovier H. Immunogenicity of a 16.7 kDa Mycobacterium paratuberculosis antigen. Microbial Pathogenesis. 2003;34(2):81–90. doi: 10.1016/s0882-4010(02)00209-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adams JL, Collins MT, Czuprynski CJ. Polymerase chain reaction analysis of TNF-α and IL-6 mRNA levels in whole blood from cattle naturally or experimentally infected with Mycobacterium paratuberculosis. Canadian Journal of Veterinary Research. 1996;60(4):257–262. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barouch DH, Santra S, Tenner-Racz K, et al. Potent CD4+ T cell responses elicited by a bicistronic HIV-1 DNA vaccine expressing gp120 and GM-CSF. Journal of Immunology. 2002;168(2):562–568. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rainczuk A, Scorza T, Spithill TW, Smooker PM. A bicistronic DNA vaccine containing apical membrane antigen 1 and merozoite surface protein 4/5 can prime humoral and cellular immune responses and partially protect mice against virulent Plasmodium chabaudi adami DS malaria. Infection and Immunity. 2004;72(10):5565–5573. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.10.5565-5573.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J, Gujar SA, Cova L, Michalak TI. Bicistronic woodchuck hepatitis virus core and gamma interferon DNA vaccine can protect from hepatitis but does not elicit sterilizing antiviral immunity. Journal of Virology. 2007;81(2):903–916. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01537-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kadam M, Shardul S, Bhagath JL, Tiwari V, Prasad N, Goswami PP. Coexpression of 16.8 kDa antigen of Mycobacterium avium paratuberculosis and murine gamma interferon in a bicistronic vector and studies on its potential as DNA vaccine. Veterinary Research Communications. 2009;33(7):597–610. doi: 10.1007/s11259-009-9207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dertzbaugh MT. Genetically engineered vaccines: an overview. Plasmid. 1998;39(2):100–113. doi: 10.1006/plas.1997.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambrook J, Russel DW. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 3 edition. Cold spring Harbor, NY, USA: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deb R, Goswami PP. Expression of a Gene Encoding 34.9 kDa PPE Antigen of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis in E. coli. Molecular Biology International. 2010;2010:7 pages. doi: 10.4061/2010/628153. Article ID 628153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moss MT, Green EP, Tizard ML, et al. Specific detection of Mycobacterium paratuberculosis by DNA hybridization with a fragment of the insertion element IS900. Gut. 1991;32:395–398. doi: 10.1136/gut.32.4.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Engwal E, Pearlman P. Enzyme linked immunosorbent (ELISA), qualitative assay of immunoglobulin G. Immunochemistry. 1971;8(9):871–874. doi: 10.1016/0019-2791(71)90454-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hope AF, Kluver PF, Jones SL, Condron RJ. Sensitivity and specificity of two serological tests for the detection of ovine paratuberculosis. Australian Veterinary Journal. 2000;78(12):850–856. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2000.tb10508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olsen I, Wiker HG, Johnson E, Langeggen H, Reitan LJ. Elevated antibody responses in patients with Crohn’s disease against a 14-kDa secreted protein purified from Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology. 2001;53(2):198–203. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2001.00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harris NB, Barletta RG. Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis in Veterinary Medicine. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2001;14(3):489–512. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.3.489-512.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flynn JL. Immunology of tuberculosis and implications in vaccine development. Tuberculosis. 2004;84(1-2):93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sweeney RW, Jones DE, Habecker P, Scott P. Interferon-γ and interleukin 4 gene expression in cows infected with Mycobacterium paratuberculosis. American Journal of Veterinary Research. 1998;59(7):842–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stabel JR. Cytokine secretion by peripheral blood mononuclear cells from cows infected with Mycobacterium paratuberculosis. American Journal of Veterinary Research. 2000;61(7):754–760. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.2000.61.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coussens PM, Verman N, Coussens MA, Elftman MD, McNulty AM. Cytokine gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and tissue of cattlenfected with Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis : evidence for an inherent proinflammatory gene expression pattern. Infection and Immunity. 2004;72(3):1409–1422. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.3.1409-1422.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin E, Kamath AT, Triccas JA, Britton WJ. Protection against virulent Mycobacterium avium infection following DNA vaccination with the 35-kilodalton antigen is accompanied by induction of gamma interferon-secreting CD4+ T cells. Infection and Immunity. 2000;68(6):3090–3096. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.6.3090-3096.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chambers MA, Williams A, Hatch G, et al. Vaccination of guinea pigs with DNA encoding the mycobacterial antigen MPB83 influences pulmonary pathology but not hematogenous spread following aerogenic infection with Mycobacterium bovis. Infection and Immunity. 2002;70(4):2159–2165. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.4.2159-2165.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pardini M, Giannoni F, Palma C, et al. Immune response and protection by DNA vaccines expressing antigen 85B of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2006;262(2):210–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sechi LA, Mara L, Cappai P, et al. Immunization with DNA vaccines encoding different mycobacterial antigens elicits a Th1 type immune response in lambs and protects against Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis infection. Vaccine. 2006;24(3):229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.08.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andersen P. TB vaccines: progress and problems. Trends in Immunology. 2001;22(3):160–168. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)01865-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaufmann SHE. How can immunology contribute to the control of tuberculosis? Nature Reviews Immunology. 2001;1(1):20–30. doi: 10.1038/35095558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goldsby RA, Kindt TJ, Osborne BA, Kuby J. Immunology. 5th edition. New York, Ny, USA: W.H. Freeman and Company, New York Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiao S, Chen H, Fang L, et al. Comparison of immune responses and protective efficacy of suicidal DNA vaccine and conventional DNA vaccine encoding glycoprotein C of pseudorabies virus in mice. Vaccine. 2004;22(3-4):345–351. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Basagoudanavar SH, Goswami PP, Tiwari V. Cellular immune responses to 35 kDa recombinant antigen of mycobacterium avium paratuberculosis. Veterinary Research Communications. 2006;30(4):357–367. doi: 10.1007/s11259-006-3253-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chow YH, Huang WL, Chi WK, Chu YID, Tao MIH. Improvement of Hepatitis B Virus DNA Vaccines by Plasmids Coexpressing Hepatitis B Surface Antigen and Interleukm-2. Journal of Virology. 1997;71(1):169–178. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.169-178.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu X, Venkataprasad N, Thangaraj HS, et al. Functions and Specificity of T Cells Following Nucleic Acid Vaccination of Mice Against Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection. Journal of Immunology. 1997;158(12):5921–5926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lefèvre P, Denis O, De Wit L, et al. Cloning of the gene encoding a 22-kilodalton cell surface antigen of Mycobacterium bovis BCG and analysis of its potential for DNA vaccination against tuberculosis. Infection and Immunity. 2000;68(3):1040–1047. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1040-1047.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kamath AT, Hanke T, Briscoe H, Britton WJ. Co-immunization with DNA vaccines expressing granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and mycobacterial secreted proteins enhances T- cell immunity, but not protective efficacy against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Immunology. 1999;96(4):511–516. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00703.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scheerlinck JPY, Casey G, McWaters P, et al. The immune response to a DNA vaccine can be modulated by co-delivery of cytokine genes using a DNA prime-protein boost strategy. Vaccine. 2001;19(28-29):4053–4060. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(01)00133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parra M, Cadieux N, Pickett T, Dheenadhayalan V, Brennan MJ. A PE protein expressed by Mycobacterium avium is an effective T-cell immunogen. Infection and Immunity. 2006;74(1):786–789. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.1.786-789.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Basagoudanavar SH, Goswami PP, Tiwari V, Pandey AK, Singh N. Heterologous expression of a gene encoding a 35 kDa protein of Mycobacterium avium paratuberculosis in Escherichia coli. Veterinary Research Communications. 2004;28(3):209–224. doi: 10.1023/b:verc.0000017371.68083.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shin SJ, Yoo HS, McDonough SP, Chang YF. Comparative antibody response of five recombinant antigens in related to bacterial shedding levels and development of serological diagnosis based on 35 kDa antigen for Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis. Journal of Veterinary Science. 2004;5(2):111–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kathaperumal K, Kumanan V, McDonough S, et al. Evaluation of immune responses and protective efficacy in a goat model following immunization with a coctail of recombinant antigens and a polyprotein of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis. Vaccine. 2009;27(1):123–135. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Flynn JL, Chan J. Immunology of tuberculosis. Annual Review of Immunology. 2001;19:93–129. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]