Abstract

Endohedral metallofullerenes, a novel form of carbon-related nanomaterials, currently attract wide attention for their potential applications in biomedical fields such as therapeutic medicine. Most endohedral metallofullerenes are synthesized using C60 or higher molecular weight fullerenes because of the limited interior volume of fullerene. It is known that the encapsulated metal atom has strong electronic interactions with the carbon cage in metallofullerenes. Gd@C82 is one of the most important molecules in the metallofullerene family, known as Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) contrast agent candidate for diagnostic imaging. Gadolinium endohedral metallofullerenol (e.g., Gd@C82(OH)22) is a functionalized fullerene with gadolinium trapped inside carbon cage. Our group previously demonstrated that the distinctive chemical and physical properties of Gd@C82(OH)22 are dependent on the number and position of the hydroxyl groups on the fullerene cage. The present article summarizes our latest findings of biomedical effects of Gd@C82(OH)22 and gives rise to a connected flow of the existing knowledge and information from experts in the field. It briefly narrates the synthesis and physico-chemical properties of Gd@C82(OH)22. The polyhydroxylated nanoparticles exhibit the enhanced water solubility and high purity, and were tested as a MRI contrast agent. Gd@C82(OH)22 treatment inhibited tumor growth in tumor-bearing nude mice. Although the precise mechanisms of this action are not well defined, our in vitro data suggest involvements of improved immunity and antioxidation by Gd@C82(OH)22 and its size-based selective targeting to tumor site. The review critically analyzed the relevant data instead of fact-listing, and explained the potential for developing Gd@C82(OH)22 into a diagnostic or therapeutic agent.

1. INTRODUCTION

Fullerene is a class of sphere-shaped molecule made exclusively of carbon atoms.1 Due to the unique structures and properties, fullerenes exhibit various activities and hence have attracted considerable attention in recent years.2, 3 Because its nanoscale carbon-cage can be easily modified with various given chemical groups for desired biomedical functions, biomedical applications have been proposed.4-6 Among all the spherical fullerene variants, the C60 variant and its derivatives have been widely studied. Furthermore, metallofullerenes, the complexes of metal-containing fullerenes, are also very important fullerene variants. Endohedral metallofullerenes, encapsulated metal atom inside fullerene, offer a bright prospect for medicine and pharmaceutics in that they present a unique motif with “super chelation” due to entrapment of metal ions in the fullerene interior space.

Gd@C82(OH)22 is a new type of metallofullerenol molecule, and has great potential for medicine and bio-pharmaceutics based on the recent studies conducted by our group. Our studies indicated that Gd@C82(OH)22 treatment could specifically inhibit the tumor growth in vivo due to reduction in tumor-induced oxidative stress rather than direct cytotoxicity to tumor cells. Gd@C82(OH)22 exhibits distinctive biomedical properties, which is characterized by inhibiting the growth of abnormal or cancer cells in pathological condition. Based on the unique physico-chemical characteristic and exclusive biological behaviors of metallofullerene, it illustrates the potential to employ Gd@C82(OH)22 as the diagnostic or therapeutic medicine for the promising medical applications in this study.

2. CHARACTERIZATION OF Gd@C82(OH)22 NANOPARTICLES

Carbon fullerenes represent a third allotrope of carbon different from both diamond and graphite in their physical and chemical properties.4 Among the fullerenes, C60 has been extensively studied for its properties because of its high purity and relatively large quantities. However, the poor water solubility has severely limited its potential for medical and biological applications. To enhance solubility of C60, several approaches have been employed including modification of the fullerenes with water-soluble substituents,7 hydrophilic groups8, 9 etc. Recently, Akiyama et al. reported that block copolymer micelles as soluble agents could improve the stability of unmodified C60 nanoparticles.10

The properties of fullerenol molecules are dependent largely on the structures and number of their outer modified groups.11, 12 Gd@C82 becomes water-soluble after polyhydroxylation through attachment of functional groups such as polyhydroxy to the cage surface of fullerenes. The resulting Gd@C82(OH)x created by our group does not physically exist as a single molecule or molecular ion but congregates into nanoparticles through molecular interactions. These nanoparticles consist of tens of molecules including magnetic cores (i.e., Gd) and closed carbon nanosheaths with surface modifications of hydroxyl groups (OH). Furthermore, the outer surface of the nanoparticles is usually embraced with water molecules through hydrogen bonds, which allow the nanoparticles to show good biocompatibility in vivo.13 Miyamoto et al. attached as many as 40 hydroxyl groups to fullerene sheath.14 Colvin et al. found that the bioactivities of fullerene derivatives could be altered largely with different outer modified groups.15 The findings indicate that a precise number of hydroxyl groups are vitally critical for biomedical properties and water solubility of metallofullerenes.

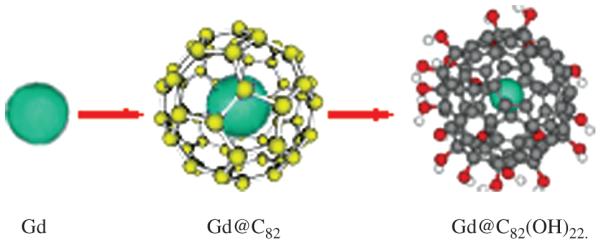

Gd@C82(OH)22 is a novel metallofullerenol with 22 hydroxyl groups synthesized by our group. The size of a single Gd@C82(OH)22 molecule is less than 2 nm, and the average size of the aggregated particles in saline solution was determined to be 22.0 nm. [Gd@C82(OH)22]n (the aggregated Gd@C82(OH)22) has very good solubility in pure water, physiological saline buffer and cell culture medium. This property provides [Gd@C82(OH)22]n with possibility to be used in medicine and pharmaceutics. The Gd@C82 was originally prepared by arcboring composite rods consisting of Gd2O3 and graphite in the He atmosphere. The Gd@C82 was purified by a two-step high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) technique in conjunction with 5PBB pre-column and Buckyprep column, respectively. Purity of the Gd@C82 product was greater than 99.5%, measured by mass spectrometry. Gd@C82(OH)x was achieved by an alkaline reaction (See Scheme 1). To obtain Gd@C82(OH)x in a narrow distribution region based on the hydroxyl number, the eluting fraction was collected in a time interval for only several minutes by HPLC. The molecular weight was determined by elemental analysis method, MALDI-TOF-MS technique and X-ray photoemission spectroscopy (XPS) measurement. The hydroxyl number of Gd@C82(OH)x was finally determined to be 22±2. The Gd@C82(OH)22 powder was dried and accurately weighed before use. The Gd@C82(OH)22 powder can be dissolved in 0.9% sterile saline solution for further antitumor experiments.

Scheme 1.

The proposed formation and structures of Gd, Gd@C82, Gd@C82(OH)22.

2.1. Gadolinium Endohedralfullerene-Based Contrast Agents and Radiotracers

Molecular imaging is a new frontier for diagnostic medicine and nanosystemic pharmaceutics.16-18 Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) as a noninvasive and convenient imaging technique has been widely used in clinical diagnosis. During the last 20 years, superparamagnetic particles were evaluated as contrast agents for imaging anatomy and function of organs and tissues in clinical studies in term of the ability to efficiently reduce the nuclear spin relaxation time of water protons.19, 20 Endohedral metallofullerenes, as the new member of the fullerene family, have great potential to be applied as radiopharmaceuticals,21 MRI contrast agents.22-24

Recently, the application of water-soluble gadolinium-containing endohedral fullerenes as MRI contrast agents has been extensively investigated,24-29 because they have many attractive properties, such as the high proton relaxivity and low toxicity which is expected due to the toxic heavy Gd3+ ion being protected by the biocompatible carbon cage. Furthermore, metallofullerenes can be modified by various functional groups to endow some new properties, such as Diels–Alder reaction,30-32 Bingel reactions,27, 33 Prato reactions.34-37 Therefore, the water-soluble gadolinium-containing endohedral fullerenes are expected to be the promising next-generation of MRI contrast agents. The polyhydroxylated gadolinium metallofullerenols, Gd@C82(OH)x, have been studied as high efficient contrast agents for MRI,38 and the size of Gd@C82(OH)x aggregated in aqueous solution is closely related to their high efficiency as a MRI agent.39

2.2. Anticancer Activity of Gd@C82(OH)22 Nanoparticles

The fullerenes have the ability to photosensitize transition of molecular oxygen to highly reactive oxygen species (ROS). This special property makes them to be used as promising candidates for the photodynamic killing of cancer cells. The attractive advantage of this therapeutic approach is effective selectivity; tumor-specific photosensitizing agents can be activated by a highly focused light beam, and delivered to tumor region at the surface of the body or to internal tumors using optical fibers.40-42 Up to the present, there are many studies demonstrating the efficient photodynamic action of various water-soluble C60 derivatives against different types of cultured cancer cells (cervical, larynx, lung and colon carcinoma) and malignant tumors in vivo.43 The observed anticancer mechanism of fullerene derivatives was largely dependent on the generation of ROS, such as singlet oxygen and superoxide anion.44-46

The antitumor activity of water-soluble fullerene derivatives involves the induction of the “programmed” cell death, known as apoptosis.44, 45 The molecular mechanism is related with activation of the caspase enzyme family and fragmentation of DNA, followed by recognition and removal of apoptotic cells by phagocytes in the absence of inflammation.47 Furthermore, there might also include other mechanisms such as ROS-dependent anticancer activity. It was reported that polyhydroxylated fullerene was able to suppress proliferation and induce apoptosis of tumor cells in presence of photosensitization and ROS production.48, 49 On the other hand, as a valid therapeutic strategy, tumor-selective delivery could transport drug molecules through abnormal endothelial pores inside tumor vasculature.50 The size of fullerene (less than the pores) makes it a potential candidate for anticancer agent and/or drug carrier.51 However, it is still not well understood of the exact mechanism of fullerene in anticancer therapy and other biomedical applications.

The antineoplastic activity of [Gd@C82(OH)22]n has been investigated by our group for many years. Our results showed that [Gd@C82(OH)22]n exhibit a very high antineoplastic efficiency (~60%) in mice, nearly without toxicity in vivo and in vitro. Unlike conventional antineoplastic chemicals such as CTX (cyclophosphamide) and cisplatin, the high antitumor efficiency of nanoparticles is not due to toxic effects to cells because they do not kill the tumor cells directly, therefore, [Gd@C82(OH)22]n particles do not cause adverse effects on important organs in vivo. Instead, the antitumor efficacy of [Gd@C82(OH)22]n can be attributed to the improved immunity, high antioxidation, and/or size-based selective penetration of [Gd@C82(OH)22]n particles into tumor cells. It is known that tumor vasculature is ‘leaky’ and characterized by much larger endothelial pores in comparison with that of normal tissues. A tumor-selective delivery of the anticancer drug molecules represents a valid therapeutic strategy.41, 50

2.3. Immunomodulation of Gd@C82(OH)22 Nanoparticles

The evidences showed that ROS status plays a very important role in the development of many human diseases, such as stroke, trauma, neurodegenerative disorders and cancer.52 Different fullerenes and derivatives have different effect on ROS production. For example, sulfobytylated C60 could down-regulate ROS production and have the biological effect of neuroprotection;53 C60-porphyrin could improve the ROS production in cancer cell cultured in vitro, Increased ROS induced cancer cell death.44

Our studies indicate that [Gd@C82(OH)22]n nanoparticle could also regulate ROS production in vivo. MDA (malondialdehyde) is a biomarker of lipid peroxidation which indicates the level of cell damage. In comparison with the control group treated by saline, administration of [Gd@C82(OH)22]n to mice decreased the MDA level. The decreased MDA level was parallel to the reduction of free radicals after treatment with [Gd@C82(OH)22]n nanoparticles. In addition, the activities of antioxidative enzymes, GSH-Px, CAT and SOD et al., were upregulated with treatment of [Gd@C82(OH)22]n nanoparticles compared to that of saline group. All these results indicate the direct inhibition by [Gd@C82(OH)22]n on ROS production. Many researchers demonstrated that carboxy-fullerenes could disturb cellular activities in different cell types such as neuronal cells,54 hepatoma cells,55 human peripheral blood mononuclear cells56 or epithelial cells.57, 58 It is possible for [Gd@C82(OH)22]n nanoparticles to act as a regulator to keep the balance between oxidative and antioxidative systems in tumor-bearing mice.

In addition to the crucial role in cell death/survival, ROS are the key effectors in signal transduction in various cell types, not only in those involved in immunomodulation against microbes and tumor cells, but also in self-tissue destruction in chronic inflammatory disorders such as autoimmunity and allergy.59 ROS-dependent intracellular signaling appears to be mediated mainly by activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade and transcription factor NF-κB.60 Due to the importance of these signaling pathways in activation of macrophages, lymphocytes and other immune cells,60, 61 fullerene-based agents as ROS-modulator are potential candidates for developing new therapies to modulate immunity in chronic inflammatory conditions such as infection and cancer.62

Fullerenes were also known to modulate immune effect by interfering with cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. TNF is an important cytokine that suppresses carcinogenesis and excludes infectious pathogens to maintain homeostasis. The cytotoxic effect of TNF-α depends on its ability to trigger ROS production in target cells.63, 64 It has been demonstrated that malonic acid C60 derivatives can protect human peripheral blood mononuclear cells from oxidative stress-dependent apoptosis induced by combination of TNF and cycloheximide.56 However, the effects of other fullerene derivatives on TNF-induced cell death have not been investigated to date. Harhaji et al.65 suggested that nanocrystalline and polyhydroxylated fullerenes modulated differently the TNF toxicity to L929 mouse fibrosarcoma cell line, which is widely used as a model system for exploring TNF-induced cell death. These findings are relevant to fullerenes as possible anticancer or cytoprotective therapeutics. Furthermore, fullerene mediated protection might be useful in preventing TNF-mediated tissue damage in TNF-used clinical therapy or various inflammatory/autoimmune conditions.

In our study, we found that [Gd@C82(OH)22]n significantly improved immunomodulation and interfered with tumor invasion, probably, by a ROS-dependent mechanism. The enhanced immunity can induce lymphocyte proliferation and neutrophil migration into tumor tissue. We analyzed and compared the immune related gene expression patterns of breast cancer cell line MCF-7 treated with or without [Gd@C82(OH)22]n using spotted cDNA microarrays. The results showed that treatment of MCF-7 cell line with [Gd@C82(OH)22]n significantly upregulated those genes closely related to immunoregulation. For instance, the activity of IL20 and IL7R genes were increased by 10.4 and 11.6 folds, respectively, after the [Gd@C82(OH)22]n treatment (Table I). IL-20 belongs to the IL-10 family and plays a role in skin inflammation and the development of hematopoietic cells. It is a pleiotropic cytokine with potent inflammatory, angiogenic, and chemoattractive characteristics.66 IL-7 receptor signaling is a participant in the formation of the transcription factor network during B lymphopoiesis by up-regulating EBF, allowing stage transition from the pre–pro-B to further maturational stages. So the results indicated that [Gd@C82(OH)22]n could affect on the immune system by modulating the cytokines expression.

Table I.

Genes upregulated in human breast cancer MCF-7 cells treated with [Gd@C82(OH)22]n nanoparticles

Furthermore, treatment of tumor bearing mice with [Gd@C82(OH)22]n clearly caused lymphocyte hyperplasia (lymphopoiesis) and aggregated follicles around the transplanted tumor tissues (data not shown). Although [Gd@C82(OH)22]n shows ability to modulate the immune system, further studies are needed to clarify the mechanisms.

2.4. Cytotoxicity of Gd@C82(OH)22 Nanoparticles

Although fullerene C60 was thought to be relatively inactive, several researchers have demonstrated that aggregated fullerene C60 has a negative effect on animals, organs, and microorganisms.67-70 Zhu et al. found that fullerene C60 in solution could lead two aquatic species, daphnia and fat-head minnow, to die.67 Oberdorster reported that uncoated fullerenes can cause oxidative damage and depletion of total glutathione (GSH) level in vivo.51 Fortner et al. illustrated the inhibitory growth and aerobic respiration rates in prokaryotic species under exposure to nano-C60 at relatively low concentrations.71

The cytotoxicity of fullerene C60 was also investigated in mammalian cells. For example, Isakovic et al. reported that fullerene C60 suspension was at least three-fold more toxic than water-soluble polyhydroxylated fullerene on mouse L929 fibrosarcoma, rat C6 glioma, and U251 human glioma cell lines.48, 72 However, Jia et al. observed no significant toxicity for fullerene C60 up to 226 μg/ml in alveolar macrophage cells. Han et al. measured the cytotoxicity of fullerene nanoparticles on two mammalian cell lines, Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells and Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells. Their results indicated that the cell mortality was increased with higher fullerene concentration and longer incubation time.73

In addition, dispersion stability is another important issue in toxicological studies of fullerene. For the interaction of C60 nanoparticles with biological molecules, dispersion stability could be different in physiological environments compared to that in model systems.74-76 When the dispersion stability of C60 nanoparticles was measured in physiological conditions, Deguchi et al. found that the human serum albumin (HSA) molecules could attach on the surfaces of C60 nanoparticles, thereby forming a protective layer to prevent coagulation. This mechanism is helpful to explore the interaction between living cells and fullerene nanoparticles.77-79

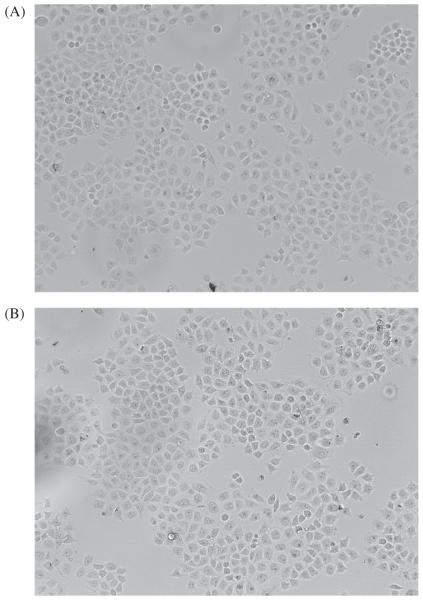

As mentioned above, there is current controversy on the toxicity of C60 fullerene. Compared to other fullerenes, [Gd@C82(OH)22]n is interesting because the [Gd@C82(OH)22]n particles seem to be nontoxic to tumor cell proliferation in vitro. The effect of [Gd@C82(OH)22]n on tumor cell growth was investigated in MCF-7 cells. After 3 days exposure of MCF-7 cells to 100 μM of [Gd@C82(OH)22]n, the total cell number was lower in the [Gd@C82(OH)22]n treated cells than the untreated control. However, there were less than 5% dead cells in the [Gd@C82(OH)22]n treated cells measured by the trypan blue exclusion assay (Fig. 1). This observation implies that [Gd@C82(OH)22]n is likely to inhibit the tumor cells not by direct cytotoxicity, rather by other indirect mechanisms such as cell cycle extension and/or metabolism reduction.

Fig. 1.

Morphological observation of MCF-7 cells treated with (A) or without (B) [Gd@C82(OH)22]n(100 μM) for 3 days. (magnification ×100).

3. CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

Many steps have been taken forward since the early biological experiments concerning C60 or other fullerenes. The research in this field is very active and new discoveries are expected to occur at any time soon. The research results demonstrate that fullerenes and fullerenes derivatives have great potential for a wide variety of biological applications including anticancer treatment and photodynamic therapy. Considering the unique structures and properties of fullerenes that are in fact unequalled in nature, the biomedical applications of each and every fullerene need to be individually exploited.

Endohedral metallofullerene have core metal surrounded by carbon cage, so they have some distinct characteristics and applications compared with C60 fullerene derivatives, such as contrast agents; and the mechanisms of their anti-tumor activity have also different because of their structural, electronic and solid state properties differences. As a new type of metallofullerene with high antineoplastic activity, [Gd@C82(OH)22]n displays very attractive properties for medical and biopharmaceutical applications.80 [Gd@C82(OH)22]n nanoparticles are soluble in aquatic system with very low toxicity compared to traditional fullerenes such as C60. The anticancer outcome of the [Gd@C82(OH)22]n nanoparticles is significant in tumorbearing mice. The results indicate that [Gd@C82(OH)22]n is a potential and promising candidate for tumor treatment and deserves further pharmaceutical development.81 However, additional studies need to be conducted to exploit the mechanisms of actions of [Gd@C82(OH)22]n.

Acknowledgments

This work is financially supported by the Collaborating Program of China-Finland Nanotechnology (2008DFA01510) and the National Basic Research Program of China (2009CB930200). This work was partially supported by US DOD USAMRMC W81XWH-050100291, NIH 2U54 CA091431-06A1 and 2G12RR003048 from RCMI program.

References and Notes

- 1.Kroto HW, Heath JR, O’Brien SC, Curl RF, Smalley RE. Nature. 1985;318:162. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Da Ros T, Prato M. Chem. Commun. 1999;8:663. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao YL, Xing GM, Chai ZF. Nature. Nanotech. 2008;3:191. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curl RF, Smalley RE. Science. 1988;242:1017. doi: 10.1126/science.242.4881.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao YX, Liu NQ, Chen CY, Luo YF, Li YF, Zhang ZY, Zhao YL, Zhao BL, Iida A, Chai ZF. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 2008;23:1121. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakamura E, Isobe H. Acc. Chem. Res. 2003;36:807. doi: 10.1021/ar030027y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang B, Feng WY, Zhu MT, Wang Y, Wang M, Gu YQ, yang H, Wang HJ, Li M, Zhao YL, Chai ZF, Wang HF. J. Nanopart. Res. 2009;11:41. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hungerbuhler H, Guldi DM, Asmus KD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:3386. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bensasson RV, Bienvenue E, Dellinger M, Leach S, Seta P. J. Phys. Chem. 1994;98:3492. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akiyama M, Ikeda A, Shintani T, Doi Y, Kikuchi J, Ogawa T, Yogo K, Takeya T, Yamamoto N. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008;6:1015. doi: 10.1039/b719671g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xing GM, Zhang J, Zhao YL, Tang J, Zhang B, Gao XF, Yuan H, Qu L, Cao WB, Chai ZF. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2004;108:11473. doi: 10.1021/jp0487962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang J, Xing GM, Yuan H, Cao WB, Jing L, Gao XF, Qu L, Cheng Y, Zhao YL, Chai ZF, Ibrahim K, Qian HJ. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2005;109:8779. doi: 10.1021/jp050374k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen CY, Xing GM, Wang J, Zhao YL, Li B, Tang J, Jia G, Wang T, Sun J, Xing L, Yuan H, Gao YY, Meng H, Chen Z, Zhao F, Chai ZF, Fang X. Nano Lett. 2005;5:2050. doi: 10.1021/nl051624b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyamoto A, Okimoto H, Shinohara H, Shibamoto Y. Eur. Radiol. 2006;16:1050. doi: 10.1007/s00330-005-0064-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sayes CM, Fortner JD, Guo W, Lyon D, Boyd AM, Ausman KD, Tao YJ, Sitharaman B, Wilson LJ, Hughes JB, West JL, Colvin VL. Nano Lett. 2004;4:1881. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wickline SA, Lanza GM. J. Cell Biochem. 2002;39:90. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heath JR, Phelps ME, Hood L. Mol. Imag. Biol. 2003;5:312. doi: 10.1016/j.mibio.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang ZY, Zhao YL, Chai ZF. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2009;54:173. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lauffer RB. Chem. Rev. 1987;87:901. [Google Scholar]

- 20.André E, Merbach ET. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd.; 2001. p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cagle DW, Kennel SJ, Mirzadeh S, Alford JM, Wilson LJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:5182. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mikawa M, Kato H, Okumura M, Narazaki M, Kanazawa Y, Miwa N, Shinohara H. Bioconj. Chem. 2001;12:510. doi: 10.1021/bc000136m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kato H, Kanazawa Y, Okumura M, Taninaka A, Yokawa T, Shinohara H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:4391. doi: 10.1021/ja027555+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shu CY, Gan LH, Wang CR, Pei XL, Han HB. Carbon. 2006;44:496. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shu CY, Zhang EY, Xiang JF, Zhu CF, Wang CR, Pei XL, Han HB. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2006;110:15597. doi: 10.1021/jp0615609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson SA, Lee KK, Frank JA. InVest. Radiol. 2006;41:332. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000192420.94038.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fatouros PP, Corwin FD, Chen ZJ, Broaddus WC, Tatum JL, Kettenmann B, Ge Z, Gibson HW, Russ JL. Radiology. 2006;240:756. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2403051341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sitharaman B, Tran LA, Pham QP, Bolskar RD, Muthupillai R, Flamm SD, Mikos AG, Wilson LJ. Contrast Media Mol. I. 2007;2:139. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laus S, Sitharaman B, Toth E, Bolskar RD, Helm L, Wilson LJ, Merbach AE. J. Phys. Chem. 2007;111:5633. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iezzi EB, Duchamp JC, Harich K, Glass TE, Lee HM, Olmstead MM, Balch AL, Dorn HC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:524. doi: 10.1021/ja0171005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stevenson S, Stephen RR, Amos TM, Cadorette VR, Reid JE, Phillips JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:12776. doi: 10.1021/ja0535312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maeda Y, Miyashita J, Hasegawa T, Wakahara T, Tsuchiya T, Nakahodo T, Akasaka T, Mizorogi N, Kobayashi K, Nagase S, Kato T, Ban N, Nakajima H, Watanabe Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:12190. doi: 10.1021/ja053983e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cardona CM, Kitaygorodskiy A, Echegoyen L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:10448. doi: 10.1021/ja052153y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cardona CM, Kitaygorodskiy A, Ortiz A, Herranz MA, Echegoyen L. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:5092. doi: 10.1021/jo0503456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamada M, Wakahara T, Nakahodo T, Tsuchiya T, Maeda Y, Akasaka T, Yoza K, Horn E, Mizorogi N, Nagase S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:1402. doi: 10.1021/ja056560l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cai T, Xu L, Anderson MR, Ge Z, Zuo T, Wang X, Olmstead MM, Balch AL, Gibson HW, Dorn HC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:8581. doi: 10.1021/ja0615573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen N, Zhang EY, Tan K, Wang CR, Lu X. Org. Lett. 2007;9:2011. doi: 10.1021/ol070654d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colvin VL. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:1166. doi: 10.1038/nbt875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu X, Xu JX, Shi ZJ, Sun BY, Gu ZN, Liu HD, Han HB. Chem. J. Chinese U. 2004;25:697. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown SB, Brown EA, Walker I. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:497. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01529-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yin JJ, Lao F, Fu P, Wamer WG, Zhao YL, Wang PC, Qiu Y, Sun BY, Xing GM, Dong JQ, Liang XJ, Chen CY. Biomaterials. 2009;30:611. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.09.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang JX, Chen CY, Li B, Yu HW, Zhao YL, Sun J, Li YF, Xing GM, Yuan H, Tang J, Chen Z, Meng H, Gao Y, Ye C, Chai Z, Zhu CF, Ma BC, Fang XH, Wan LJ. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006;71:872. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mroz P, Tegos GP, Gali H, Wharton T, Sarna T, Hamblin MR. Photodynamic therapy with fullerenes. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2007;6:1139. doi: 10.1039/b711141j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alvarez MG, Prucca C, Milanesio ME, Durantini EN, Rivarola V. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2006;38:2092. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mroz P, Pawlak A, Satti M, Lee H, Wharton T, Gali H. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007;43:711. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang B, Feng WY, Wang M, Wang TC, Gu TQ, Zhu MT, yang H, Shi JW, Zhang F, Zhao YL, Chai ZF, Wang HF, Wang J. J. Nanopart. Res. 2008;10:263. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Edinger AL, Thompson CB. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2004;16:663. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Isakovic A, Markovic Z, Todorovic-Markovic B, Nikolic N, Vranjes-Djuric S, Mirkovic M. Toxicol. Sci. 2006;91:173. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen YW, Hwang KC, Yen CC, Lai YL. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2004;287:21. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00310.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hashizume H, Baluk P, Morikawa S, McLean JW, Thurston G, Roberge S. Am. J. Pathol. 2000;156:1363. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65006-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fortner JD, Lyon DY, Sayes CM, Boyd AM, Falkner JC, Hotze EM. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005;39:4307. doi: 10.1021/es048099n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rayner BS, Duong TTH, Myers SJ, Witting PK. J. Neurochem. 2006;97:211. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03726.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang SS, Tsai SK, Chih CL, Chiang LY, Hsieh HM, Teng CM. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2001;30:643. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00505-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bisaglia M, Natalini B, Pellicciari R, Straface E, Malorni W, Monti D, Franceschi C, Schettini G. J. Neurochem. 2000;74:1197. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.741197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang YL, Shen CK, Luh TY, Yang HC, Hwang KC, Chou CK. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998;254:38. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2540038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Monti D, Moretti L, Salvioli S, Straface E, Malorni W, Pellicciari R, Schettini G, Bisaglia M, Pincelli C, Fumelli C, Bonafè M, Franceschi C. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2000;277:711. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Straface E, Natalini B, Monti D, Franceschi C, Schettini G, Bisaglia M, Fumelli C, Pincelli C, Pellicciari R, Malorni W. FEBS Lett. 1999;454:335. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00812-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hu Z, Xing HP, Zhu Z, Wang W, Guan WC. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2007;18:145. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Droge W. Physiol. Rev. 2002;82:47. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gloire G, Legrand-Poels S, Piette J. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2006;72:1493. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu Y, Jiao F, Qiu Y, Li W, Lao F, Zhou GQ, Zhao YL, Sun BY, Xing GM, Dong JQ, Chai ZF, Chen CY. Biomaterials. 2009:1. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Markovic Z, Trajkovic V. Biomaterials. 2008;29:1. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Goossens V, De Vos K, Vercammen D, Steemans M, Vancompernolle K, Fiers W, Vandenabeele P, Grooten J. BioFactors. 1999;10:145. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520100210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhu MT, Feng WY, Wang Y, Wang B, Wang M, yang H, Zhao YL, Chai ZF. Toxicol. Sci. 2009;107:342. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Harhaji L, Isakovic A, Vucicevic L, Janjetovic K, Misirkic M, Markovic Z, Todorovic-Markovic B, Nikolic N, Vranjes-Djuric S, Nikolic Z, Trajkovic V. Pharmacol. Res. 2008;25:1365. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9486-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wei CC, Hsu YH, Li HH, Wang YC, Hsieh MY, Chen WY, Hsing CH, Chang MS. J. Biomed. Sci. 2006;13:601. doi: 10.1007/s11373-006-9087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhu SQ, Oberdorster E, Haasch ML. Mar. Environ. Res. 2006;62:S5. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2006.04.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jia G, Wang HF, Yan L, Wang X, Pei RJ, Yan T, Zhao YL, Guo XB. Environ. Sci. and Technol. 2005;39:1378. doi: 10.1021/es048729l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Oberdorster E. Environ. Health Perspect. 2004;112:1058. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang B, Feng WY, Wang TC, Jia G, Shi JW, Zhang F, Zhao YL, Chai ZF. Toxicol. Lett. 2006;161:115. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Meng H, Chen Z, Xing GM, Yuan H, Cheng CY, Zhao F, Zhang CC, Zhao YL. Toxicol. Lett. 2007;175:102. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li W, Zhao F, Chen CY, Zhao YL. Prog. Chem. 2009;21:430. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Han B, Karim MN. Scanning. 2008;30:213. doi: 10.1002/sca.20081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lyon DY, Adams K, Falkner JC, Alvarez PJ. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006;40:4360. doi: 10.1021/es0603655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brant JA, Labille J, Bottero JY, Wiesner MR. Langmuir. 2006;22:3878. doi: 10.1021/la053293o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li W, Chen CY, Ye C, Wei TT, Zhao YL, Lao F, Chen Z, Meng H, Gao YX, Yuan H, Xing GM, Zhao F, Chai ZF, Zhang XJ, Yang FY, Han D, Tang XH, Zhang YG. Nanotechnology. 2008;19:145102. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/19/14/145102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Deguchi S, Yamazaki T, Mukai S, Usami R, Horikoshi K. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2007;20:854. doi: 10.1021/tx6003198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen Z, Meng H, Xing GM, Chen CY, Zhao YL. Int. J. Nanotechnol. 2007;4:179. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liang XJ, Chen CY, Zhao YL, Jia L, Wang PC. Curr. Drug. Metab. 2008;9:697. doi: 10.2174/138920008786049230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ye C, Chen CY, Chen Z, Meng H, Xing L, Yuan H, Xing GM, Zhao F, Zhao YL, Chai ZF, Jiang YX, Fang XH, Han D, Chen L, Wang C, Wei TT. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2006;51:1. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yin JJ, Lao F, Meng J, Fu PP, Zhao YL, Xing GM, Gao X, Sun B, Li X, Wang PC, Chen C, Liang XJ. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008;74:1132. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.048348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]