Abstract

In vitro models of cardiac hypertrophy focus exclusively on applying “external” dynamic signals (electrical, mechanical, and chemical) to achieve a hypertrophic state. In contrast, here we set out to demonstrate the role of “self-organized” cellular architecture and activity in reprogramming cardiac cell/tissue function toward a hypertrophic phenotype. We report that in neonatal rat cardiomyocyte culture, subtle out-of-plane microtopographic cues alter cell attachment, increase biomechanical stresses, and induce not only structural remodeling, but also yield essential molecular and electrophysiological signatures of hypertrophy. Increased cell size and cell binucleation, molecular up-regulation of released atrial natriuretic peptide, altered expression of classic hypertrophy markers, ion channel remodeling, and corresponding changes in electrophysiological function indicate a state of hypertrophy on par with other in vitro and in vivo models. Clinically used antihypertrophic pharmacological treatments partially reversed hypertrophic behavior in this in vitro model. Partial least-squares regression analysis, combining gene expression and functional data, yielded clear separation of phenotypes (control: cells grown on flat surfaces; hypertrophic: cells grown on quasi-3-dimensional surfaces and treated). In summary, structural surface features can guide cardiac cell attachment, and the subsequent syncytial behavior can facilitate trophic signals, unexpectedly on par with externally applied mechanical, electrical, and chemical stimulation.—Chung, C., Bien, H., Sobie, E. A., Dasari, V., McKinnon, D., Rosati, B., Entcheva, E. Hypertrophic phenotype in cardiac cell assemblies solely by structural cues and ensuing self-organization.

Keywords: cardiomyocytes, cell culture, electrophysiology, natriuretic peptides

Local cues from the cell environment are fundamental to programming cell fate in vivo across multiple cell types. From mesenchymal stem cells (1) to neuronal precursors (2) or endothelial cells (3), significant alterations in cellular processes occur in response to the microenvironment, often driven by mechanotransduction. A common limitation in traditional cell culture models is the lack of 3-dimensional (3-D) architecture to provide cues found in the complex, nonplanar structures of native tissue (4). The desire to circumvent this limitation has led to the use of microfabrication technology to better reflect native or diseased tissue architecture for in vitro cell or tissue studies (5, 6).

In cardiac tissue, several diseases exemplify the relationship between structure and function in a pathological scenario. Cardiac hypertrophy, for instance, is a consequence of increased biomechanical stress, and is associated with clinical conditions, including ischemia, hypertension, myocardial infarction, and valvular diseases. In all of the above cases, increased biomechanical stress results in myocardial tissue remodeling as a compensatory mechanism by the addition of sarcomeres, either in series (eccentric hypertrophy) or in parallel (concentric hypertrophy) (7). This structural remodeling is paralleled by increased protein synthesis and significant changes in gene expression (8). Initially an adaptive response that helps to maintain cardiac output in the face of greater work demand, in the long term, cardiac hypertrophy can lead to more serious conditions, such as arrhythmias and ultimately heart failure. At the cellular level, a ubiquitous physiological sign of hypertrophy is weakened lusitropic action, prompted by prolongation of the action potential (AP), as depolarized membrane potentials inhibit Ca2+ removal via Na+-Ca2+ exchange. AP prolongation results from remodeling of ion channels, particularly down-regulation of repolarizing K+ currents (9, 10). This abnormal repolarization and relaxation can, in turn, contribute to the initiation of either triggered or reentrant arrhythmias (9, 11).

To study the complex sequence of remodeling events, 3 main types of dynamic exogenous stimuli have been previously used in vitro for induction of myocyte hypertrophy: cyclic mechanical stretch of relatively large strains (20%) (12), chronic electrical stimulation at high rates (3 Hz) (13), and adrenergic or other chemical stimulation (14, 15). In contrast, here, in the absence of exogenous stimulation, we sought to demonstrate the role played by altered cellular architecture and ensuing self-organized syncytial behavior in reprogramming cardiac cell and tissue function.

Drawing on previously demonstrated strong effects of cell shape and cell-matrix interactions on cell fate (3), we hypothesized that in a multicellular cardiomyocyte setting, subtle out-of-plane microtopographic cues would alter cell attachment, morphology, and syncytial organization and behavior, producing a more mature and potentially hypertrophic phenotype. Using such intrinsic response to scaffold topography alone, we demonstrate not only structural remodeling but also successful capture of essential molecular and electrophysiological changes found in hypertrophy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cardiomyocyte cell culture

Neonatal rat cardiac myocytes were cultured for 5 to 7 d on polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) scaffolds with grooved anisotropic features or flat isotropic surfaces for all experiments (see Fig. 1A), as described previously (16–18). Briefly, myocytes from the ventricular portion (lower 70%) of the hearts of 3-d-old neonatal Sprague-Dawley rats were isolated by enzymatic digestion overnight with trypsin (1 mg/ml, 4°C; USB Corp., Cleveland, OH, USA), then collagenase (1 mg/ml, 37°C; Worthington, Lakewood, NJ, USA). After 90 min of preplating to remove the fibroblast population, myocytes were plated at high density (4×105 cells/cm2) onto fibronectin-coated PDMS (Sylgard 184; Dow Corning, Midland, MI, USA) scaffolds with microtopographical features produced by molding onto metal templates fabricated by acoustic micromachining (18, 19). Cells were maintained in culture medium with 10% FBS (Invitrogen, Carslbad, CA, USA) on d 1 and 2, and 2% FBS culture medium thereafter, with medium change every other day.

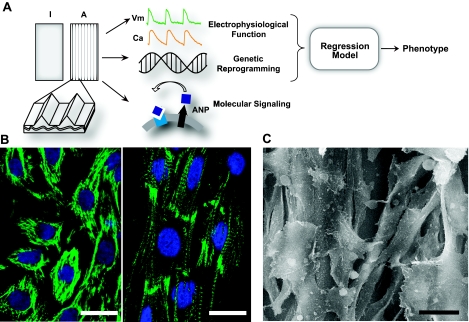

Figure 1.

Cardiac syncytia grown in plane and under topographic guidance. A) Three-dimensional scaffolding—elastic polymer with fine deep grooves—was employed as a test bed for architectural influences on electrophysiological properties, genetic reprogramming, and molecular signaling in vitro. Data obtained were used in a regression model to build phenotype classifiers and/or predictors. Isotropic cultures (I) grown in plane served as controls to the topographically guided anisotropic samples (A). B) Confocal fluorescent images (green, phalloidin-labeled F-actin; blue, TOTO-3-labeled nuclei) of isotropic (left panel) and anisotropic (right panel) samples; the latter exhibited more elongated cell morphology with inline sarcomeres compared to the controls. C) Scanning electron microscopy image of an anisotropic sample demonstrating the nonplanar, 3-D nature of cell arrangement. Scale bars = 20 μm.

Visualization of cell structure with fluorescent labeling and immunocytochemistry

Fluorescent labeling and immunocytochemistry were done on the cardiac cell networks on d 5–7 after cell plating. The cell networks were fixed in 10% formalin solution, and then permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA).

To visualize cytoskeletal structure, F-actin was labeled with phalloidin-Alexa 488; nuclei were labeled with TOTO-3 or SYTO-16; all dyes were obtained from Invitrogen. Immunocytochemistry was used for labeling Connexin 43 (Cx43) gap junctional clusters. After washing with 1% FBS solution, cells were incubated overnight with primary rabbit anti-mouse Cx43 antibody (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA, USA) at 4°C. The next day, samples were washed and then incubated with secondary goat anti-rabbit antibody conjugated with Alexa 488 (Invitrogen) for 45 min. After a final washing with PBS, the stained samples were mounted onto microscope slides with a thin glass coverslip with VectaShield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) mounting medium.

Imaging of the fluorescently labeled samples was done on a Zeiss Axiovert 200 M microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Thornwood, NY, USA) using a ×63 objective (NA 1.4) or Olympus FluoView FV1000 confocal system (Olympus, Center Valley, PA, USA) using a ×60 objective (NA 1.42). Since the cell networks have a third dimension in the z axis, especially in the aligned samples, images were acquired at 1-μm steps to create a z stack. Each slice of the z stack was then projected onto a plane for full representation of gap junction formation or actin cytoskeletal network and nuclear structures.

Confocal reflectance imaging (20) was used to obtain fine 3-D details of cellular structure and cellular attachment to the scaffolds. In this modality, reflected light (instead of emitted fluorescence) is collected, and contrast is formed on the basis of local changes in the index of refraction and absorption properties of the cell cytoplasm with respect to the scaffold and the medium (20). Z stacks of images at 1-μm spacing were obtained for full reconstruction (54 confocal images in the case shown in Fig. 5A). Three-dimensional reconstructions of cellular structures and organelles within the cardiac syncytium were generated from these z stack images in multiple planes using the Slicer-Dicer software (Pixotec, Renton, WA, USA).

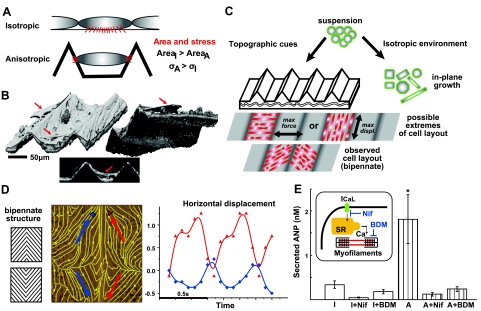

Figure 5.

Mechanism of hypertrophy development via topographic guidance. A) Proposed difference in attachment between cells grown in plane and cells grown on scaffolding with periodic topographic out-of-plane features. As anisotropic (A) cells may have more localized attachment points (smaller area) compared to the essentially flat spread-out isotropic (I) cells, for the same force of contraction, the resultant stress experienced by the anisotropic cells (σA) will be higher by simple σ considerations. B) Confirmation of “hanging” cells with out-of-plane attachments: 3-D reconstruction of the cytoskeleton in cardiac syncytium on microgrooved surface using reflectance confocal imaging (red arrow indicates hanging cell >30 μm above scaffold surface). Similar results, seen also in scanning electron microscopy images (Fig. 1), corroborate the proposed mechanism in panel A. C) Development of cardiac syncytium in plane results in isotropic properties without cell shape control, while topographic cues guide cell shape and orientation. With provided linear grooves, there are 2 possible extreme solutions for cell layout: across-groove growth would optimize force development under isometric contractions; along-groove growth would maximize displacement at lower forces developed. Actual observed cell configuration in our studies followed the grooves under an angle, forming bipennate (fishbone-like) structures (16, 17). D) Bipennate structures elicited bipennate maps of spatial displacement during myocyte contractions. Image shows displacement stream lines, as calculated by digital cross-correlation from movies of spontaneous contractions. For two selected points, antiphase horizontal displacement on both sides of the groove is shown. Arrows indicate major axes of displacement. See Supplemental Video S1 for movies of contractions. E) Confirmation of the essential role of tension development on topographic surfaces in inducing hypertrophy and concomitant enhanced secretion of ANP: Treatment with an excitation-contraction uncoupler (BDM) or a calcium channel blocker (Nif) essentially equalized the ANP secretion in isotropic and anisotropic samples. Sample size: I, n = 11; I + Nif, n = 10; I + BDM, n = 11; A, n = 10; A + Nif, n = 9; A + BDM, n = 11. *P < 0.01; 1-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey test.

Quantification of morphological features

Morphological analysis of cell size and quantification of binucleation were done in a semiautomated way in Matlab (MathWorks, Natick, MA, USA). Confocal images were taken of Cx43 and F-actin and/or samples with labeled nuclei to identify individual cells (see examples in Figs. 1B and 3A). The high magnification resulted in a small field of view (with only a few cells per image) but allowed proper cell area calculation. The confocal images were preprocessed by manual tracing of cells in Matlab; only cells with unambiguous boundaries were selected. The properties of the outlined polygonal cell shapes were automatically quantified in Matlab's Image Processing Toolbox. Regions with an area < 200 μm2 were deemed noise and removed from analysis. To eliminate possible bias in tracing, undergraduate students were used as independent masked tracers. Because of the 3-D nature of the cells in anisotropic samples and the possibility for suboptimal projection onto the confocal plane, topographically generated differences are likely underestimated, not overestimated, by this method.

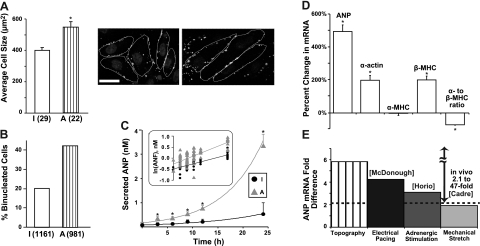

Figure 3.

Hypertrophy induction by topographic guidance alone. A) Increase in cell size was seen for anisotropic (A) vs. isotropic (I) cultures (P<0.01); number of analyzed cells in parentheses. Quantification was based on high-magnification confocal images of cytoskeletal or gap junctional staining, as shown in Fig. 1B and here (Cx43 staining and nuclear staining). Scale bar = 20 μm. B) Increased percentage of binucleated cells in anisotropic vs. isotropic cultures (42 vs. 20%); number of analyzed cells in parentheses. C) Significant increase in release of ANP across 24 h for anisotropic vs. isotropic cultures, with a significantly different slope in the logarithm of secreted ANP concentration (inset), suggesting different kinetics of release. Number of samples for ANP release at time points 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 h: for isotropic cultures, n = 3, 12, 21, 21, 5, and 11, respectively; for anisotropic cultures, n = 3, 12, 18, 21, 6, and 10, respectively. At all time points, ANP release was significantly higher in anisotropic vs. isotropic cultures (P<0.01). D) Expression of classic hypertrophy-related genetic markers was altered in anisotropic vs. isotropic cultures. More specifically, compared to isotropic controls, the anisotropic samples exhibited 5-fold increase in the mRNA for ANP, increase in skeletal α-actin and β-myosin heavy chain (MHC), and a switch from the α- to β-MHC as the dominant isoform. Number of analyzed samples: isotropic, n = 12; anisotropic, and n = 14. *P < 0.01. E) Compared to hypertrophy induction by exogenous stimulation in neonatal rat in vitro models, topographically induced increase in ANP mRNA was on par with release by fast electrical pacing, as reported by McDonough and Glembotski (13), mechanical stretching (Cadre et al., ref. 12) or adrenergic stimulation with phenylephrine (Horio et al., ref. 15). Topographically induced hypertrophy resulted in ANP mRNA within the wide range of values seen in vivo, which span from 2- to 47-fold increase.

Fully automated analysis of nuclear morphology was also done in Matlab, using custom-designed software, as described previously (16). Briefly, thresholding of grayscale nuclear images was performed, and ellipsoidal shape was automatically detected for quantification of several parameters (size, eccentricity, orientation) with an algorithm implemented in Matlab. Automatic structural analysis of Cx43 distribution and size (by granulometry) was done in Matlab as well, using custom-designed routines, as described previously (17).

Multicellular images of cytoskeletal structure (F-actin-labeled cells) were used to reveal sarcomere organization by applying the spatial 2-D FFT approach in custom-designed software in Matlab. Unlike the 1-D Fourier transform, this method can uncover fine spatial periodicities even when cell orientation varies within the analyzed field of view. In the displayed spectra from this analysis (a projected 1-D representation along the direction of highest feature periodicity), the presence of “meso” features, such as cell borders, contributes to the very low frequency content, while the sarcomeres are seen as distinct higher-frequency spatial features. The distance x of the sarcomere-related peak in the spectrum from the DC (0 frequency) point is x = N/λ, where N is the number of pixels along that dimension, and λ (μm) is the actual spacing of the sarcomeres (see Fig. 2A).

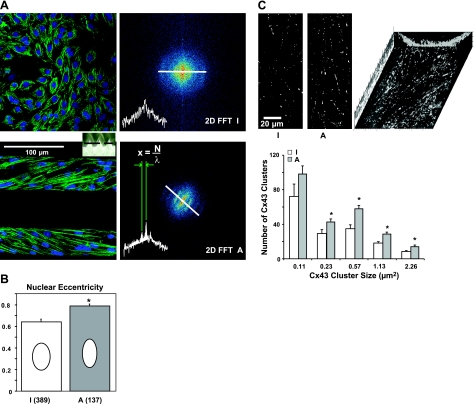

Figure 2.

Topographic guidance induces structural changes in the cytoskeleton, nucleus, and gap junctions. A) More organized sarcomeric structure is seen in anisotropic samples (bottom panels) vs. isotropic samples (top panels), as illustrated by in-register periodic sarcomeres revealed by 2-D FFT analysis. Spatial frequency λ can be determined by the distance x between the dominant (center) peak and a detected secondary peak, considering the number of pixels N in the image. B) Greater nuclear eccentricity seen in anisotropic cultures. Bars indicate 95% confidence interval; ellipses are a graphical representation of the mean nuclear geometry, scaled proportionately to the mean major and minor axis lengths. Sample size: isotropic (I), n = 389; anisotropic (A), n = 137 (P<0.05). C) Anisotropic samples have greater density and number of Cx43 clusters. Top left panel: representative processed images of Cx43 in isotropic and anisotropic samples after contrast enhancement, thresholding, and cropping. Top right panel: projected 3-D reconstruction of Cx43 in the anisotropic cultures within the scaffold grooves. Bottom panel: quantification of Cx43 cluster size and number showed larger number and density of Cx43 in anisotropic samples (n=12/group). Bars represent means ± se. These data are in concert with previously reported changes by our group (15–20). *P < 0.05 vs. corresponding isotropic controls.

Quantification of hypertrophic phenotype (release of atrial natriuretic peptide; genetic markers)

Secreted atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), a marker of hypertrophic growth (7), was quantified. Five- to 7-d-old samples were transferred to fresh 2% culture medium in order to set a common baseline starting level for all samples. After the transfer, 100 μl of culture medium with ANP secreted from the cells was collected at preestablished time points (t = 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 h) replacing with 100 μl of fresh medium to maintain a constant volume and conditions throughout the experiments. Secreted ANP levels in the collected culture medium were quantified by enzyme-link immunosorbent assay (ELISA) methods using a kit from Peninsula Labs (San Carlos, CA, USA). Sample size varied between 3 and 21/group/time point. The kinetics of ANP secretion was quantified by logarithmic transformation to linearize the raw secretion kinetics data. Statistical significance (P<0.05) was determined using a paired t test.

Primers for known genetic markers of hypertrophy (see Table 1) were developed using Primer 3 software (http://fokker.wi.mit.edu/primer3/input.htm) and verified by real-time RT-PCR and sequencing of the RT-PCR product. Samples were collected from cells across two cultures by lysing the cells using spin technology and QIAshredder columns (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). After collecting material from lysed cells and extracting total RNA using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), quantification of the hypertrophy markers was performed. RT-PCR was done on an Applied Biosystems 7300 system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) for all genes of interest. In addition to an increase in ANP as a marker of hypertrophy, we looked at transcriptional changes in structural proteins: an increase in α-skeletal actin (ACTA1) and a switch from the α-isoform (Myh6) of myosin heavy chain (MHC) to the β-isoform (Myh7) as the dominant MHC protein.

Table 1. Primers designed and used for genes of interest in real-time RT-PCR.

| Gene | Final target | Primer.up sequence | Primer.dn sequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANP | ANP | GGTACCGAAGATAACAGCCAAA | GTCCGTGGTGCTGAAGTTTA |

| ACTA1 | α-Skeletal actin | GTCGGTATGGGTCAGAAGGA | CCGGAGGCATAGAGAGACAG |

| Myh6 | α-Myosin heavy chain | CATAGGGGACCGTAGCAAGA | TTGGTAACCAGCAGCATGTC |

| Myh7 | β-Myosin heavy chain | AATCCGGAGCTGGTAAGACC | CTGGATTTTTCCAGAAGGTAGG |

| SERCa2a | SERCa2a | AGGGACTGCAGTGGCTAAGA | GGGGGTTTGTTCATGATGTC |

| Kv4.3 | Ito | GCTCCTCGGCCAGCAAGTT | GCGCTTGCTGTGCAGGTAGG |

| Cav1.2 | ICaL | ATCACCATGGAGGGCTGGAC | TGTGGGCATGCTCATGTTTCG |

| SCN5A | INa | CAGAAGAAAAAGTTAGGGGGCCAGGA | AAGAGCAGGTTGATCTTGGCCAAGATG |

| Kir2.1 | IK1 | AGAACCAACCGCTACAGCAT | CCAAAGAACAGCCAGGAGAG |

| HCN4 | If | ATATGGACCCCACTGATCCA | AGAGGAGGGCAAGAGAGGAC |

RT-PCR and optical mapping for quantification of electrophysiological remodeling (gene and function)

Genetic and functional assessment of electrophysiological remodeling was done on a sample-by-sample basis, thus pairing gene expression and functional data. Recordings of transmembrane voltage and intracellular calcium were done using optical imaging with di-8-ANEPPS and Fura-2 AM (Invitrogen), respectively, as described previously (21). Functional measurements were performed on d 5 to 7 after cell plating at 30°C in Tyrode's solution (1.33 mM Ca2+, 5 mM glucose, 5 mM HEPES, 1 mM MgCl2, 5.4 mM KCl, 135 mM NaCl, and 0.33 mM NaH2PO4, at pH 7.4).

In the experimental chamber, cells were stimulated with a Pt line electrode at one end of the rectangular scaffolds (flat or grooved), initiating a planar wave. Pacing frequency was set to 1 Hz. Fluorescence signals were recorded with a photomultiplier tube at a fixed and precisely measured distance (1.2–1.6 cm) from the electrode using a programmable motorized microscope stage at a sampling rate of 1 kHz, as described previously (21). After achieving steady state, sequential records of 20 action potentials and 20 calcium transients at the same location were stored for analysis. Delivery of a desired pacing sequence, optical filter switch, and data storage was fully automated by in-house acquisition software. Collected fluorescence signals for measurements of intracellular calcium or transmembrane voltage were temporally filtered using a polynomial filter (Savitsky-Golay) of second order and analyzed with custom-designed Matlab software for automatic calculations of action potential duration (APD), calcium transient duration (CTD) at preset levels (normally 80%), peak calcium, conduction velocity (CV), and some other morphological parameters. Propagation CV data were confirmed for a subset of samples by macroscopic optical mapping, as reported previously (21, 22). All data are represented as means ± se. Statistical significance was determined with ANOVA, followed by Tukey post hoc testing, or using a Student's t test.

After completion of functional measurements, samples were processed for extraction of mRNA and quantification of gene expression. Cells were lysed, RNA was collected, and expression levels of several voltage-gated ion channels were quantified by real-time PCR, keeping track of sample identity in order to match data to obtained functional information. Ion channel transcriptional changes were sought out to explain the functional differences between anisotropic and isotropic samples (longer APD and CTD, faster CV, increased pacemaking) in several ion channels: Ito (Kv4.3), ICaL (Cav1.2), INa (SCN5A), IK1 (Kir2.1), If (HCN4 and HCN2), and SERCa2a (Table 1). Cycle threshold values were converted to expression values by comparison with a standard curve and normalizing to expression of the 18S rRNA. Statistical significance was determined from a paired t test, with values of P < 0.05 considered significant. Sample size was n = 14 for anisotropically grown myocytes and n = 11 for isotropic controls, with samples taken from 4 cultures.

Contractility assessment

Digital cross-correlation (DCC) technique was developed and applied to analyze spatiotemporal images of mechanical activity and confirm the development of tension along the actin fibers, as shown in Fig. 5D. More specifically, 2-D deformations were determined by processing successive images using custom-designed software based on digital cross-correlation in Matlab; timing between analyzed frames was 60 ms. Image registration was provided by matching positions of random speckles from optical patterns or fine particulate imperfections on the cell surface, or cellular organelles. First, macroscopic movement or drift between frames was removed by computing the cross-correlation function. Second, subdivisions were established in the first image and compared to corresponding neighborhoods in the second image using the displacement of the maximum DCC with respect to the centroid (23, 24). Each pair of subregions was compared using a cross-correlation function, calculated in the Fourier space. The displacement vector d was determined stepwise for each pair of consecutive images, based on the calculated displacements along the x axis (horizontal displacement, u) and y axis (vertical displacement, v), i.e., the location of the correlation peak with respect to the subregion's centroid. On the basis of the displacement vector map over time, streamline fields were calculated and displayed in Matlab, as seen in Fig. 5D. Uniaxial strain was computed as the difference between the initial (diastolic) length and current length as determined through computer-assisted videomicroscopy, divided by the diastolic length.

Excitation-contraction uncoupling: stretch-activated channels

The importance of tension development for hypertrophic growth and increased ANP secretion was examined. Using excitation-contraction uncoupler, butanedione monoxime (BDM; 7.5 mM; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), or L-type calcium channel blocker [nifedipine (Nif), 0.1 mM; Sigma], cells were treated for 24 h, and ANP secretion was quantified as described above.

Because our model of hypertrophy induction is based on stress and contraction, the stretch-activated ion channels (SACs) represent potential mediators of the observed electrophysiological changes. During functional experiments, samples were paced at 1 Hz. In each sample, a control reading was taken, followed by a second reading after perfusion for 60 s with 400 nM GsMTx4 (Peptide Institute, Osaka, Japan), highly selective SAC-blocking toxin.

Intervention with exogenous natriuretic peptides

Cells were treated 24 h with 100 nM ANP or 100 nM brain natriuretic peptide (BNP; Sigma). After functional testing, as described above, cells were lysed, and RNA was collected for analysis of a combination of ion channel and hypertrophic genes or quantification of cell size.

Partial least-squares (PLS) regression

To quantify the relationship between changes in gene expression and the resulting electrophysiological phenotype, PLS regression analysis was applied (25, 26). This method is appropriate for situations in which some of the data are partially redundant, or in which the number of independent data samples is small. The regression procedure, in addition to calculating a matrix BPLS that indicates correlations between input and output variables, also computes principal axes of the input data matrix X. In contrast to those calculated using principal component analysis (PCA), these principal axes take into account not just information about the inputs but also covariance between the inputs and the outputs. PLS is therefore considered a “supervised” method, in contrast to unsupervised methods such as PCA, and a comparison of Fig. 4C with Supplemental Fig. S2 reveals that this feature does indeed lead to a cleaner separation between the experimental groups.

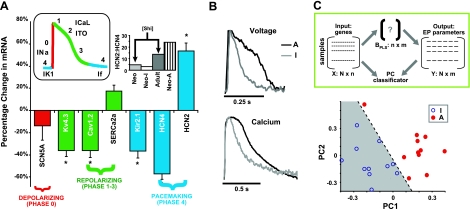

Figure 4.

Distinct genetic and functional profiles via topographic guidance. A) Genetic remodeling of major ion channels evident at the transcription level in anisotropic (A; n=14) vs. isotropic cultures (I; n=11), especially in genes regulating pacemaking (blue) and phase 4 of the action potential (see inset: actual neonatal rat AP with color-coded phases), IK1 (Kir2.1) and If (HCN4 and HCN2), as well as repolarization (green), Ito (Kv4.3) and ICaL (Cav1.2). Interestingly, the high HCN2:HCN4 ratio surpassed ratios for adult rat (Shi et al.; ref. 47), indicating a more mature and potentially hypertrophic phenotype induced by topographic guidance alone. B) Example traces of voltage and calcium for isotropic and anisotropic cultures at 1-Hz pacing. C) Classification of distinct genetic and functional profiles for isotropic vs. anisotropic cultures by PLS regression analysis. Top panel: schematic illustrates that input matrix X and output matrix Y contained gene expression data and electrophysiological measurements with preservation of sample identity, respectively (not pooled data). Each row of X and Y is a unique sample (n=22; 11 anisotropic and 11 isotropic), whereas each column corresponds to a different gene or measured quantity. The PLS procedure derives a matrix BPLS that quantifies correlations between the inputs and the outputs, and a set of principal components that indicate the most informative dimensions in the data. Bottom panel: scatterplot of the first two principal components reveals a clear separation between the istotropic and anisotropic samples when both gene expression data and physiological recordings are considered.

For our use of PLS, the input matrix X contained the gene expression data. Each column corresponded to a different gene, and each row to a different experimental sample. The 5 measured mRNA levels included were Kv4.3, Cav1.2, SCN5A, Kir2.1, and HCN4. Data in the output matrix Y were of physiological measurements, namely, action potential duration, conduction velocity, calcium transient duration, and calcium transient amplitude.

All computations were performed in Matlab using an algorithm by Dr. Herve Abdi (University of Texas, Dallas, TX, USA; http://wwwpub.utdallas.edu/∼herve/). The values displayed in Figs. 4 and 6 are of the first two columns of the scores matrix T. PLS regression was executed using the nonlinear iterative partial least squares (NIPALS) algorithm after normalization of the values in the X and Y matrices.

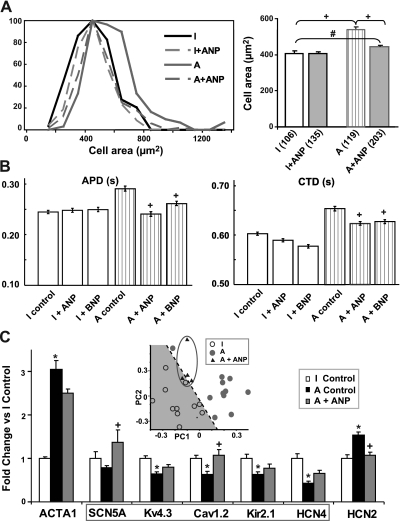

Figure 6.

Reversal of hypertrophy by exogenous natriuretic peptides. A) Direct (nonsystemic) application of exogenous ANP at high concentration (100 nM) for 24 h in vitro led to partial reversal of cell size in anisotropic (A) samples. Left panel: histograms of cell area (μm2). Right panel: average data per group (means±se). Number of analyzed cells is shown for each of the 4 groups. +P < 0.01; #P < 0.05. B) Exogenous ANP and BNP (100 nM, for 24 h) led to full or partial reversal of hypertrophy-linked prolongation of APD (left panel) and of CTD (right panel). APD and CTD levels were determined at 80% recovery to rest during 1-Hz pacing. Number of analyzed samples: I, n = 23; I + ANP, n = 23; I + BNP, n = 13; A, n = 18; A + ANP, n = 20; A + BNP, n = 12. +P < 0.01 vs. anisotropic control. C) Exogenous ANP treatment partially reversed gene expression in anisotropic samples toward normal levels for all examined (hypertrophy and ion channel) genes. When visualized in the principal component space defined by PLS regression, treated anisotropic samples (triangles) were located closer to isotropic (I) than to untreated anisotropic samples. Number of analyzed samples: I, n = 11; A, n = 14; A + ANP, n = 20. *P < 0.01 vs. isotropic control; +P < 0.01 vs. untreated anisotropic control; 1-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey test.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Three-dimensional elastic scaffolding with periodically spaced out-of-plane attachment points was used to guide the assembly of neonatal rat cardiac myocytes (see Materials and Methods for details). In response to these subtle topographic cues, creating a quasi-3-D environment, the cells self-organized into a syncytium with greater contractility than in-plane cell monolayers (17), and with evidence of hypertrophic remodeling at several hierarchical scales (Fig. 1A), as detailed below. Cardiomyocytes formed macroscopically anisotropic tissue with cells exhibiting rod-like morphology (Fig. 1B), whereas control myocyte layers grown in plane maintained an isotropic appearance. Anisotropically grown cells had a highly organized cytoskeleton with regular contractile machinery (in-line sarcomeres) Fig. 2A, as well as significantly elongated nuclei (Fig. 2B) and increased gap junctional expression (Fig. 2C). These data corroborate previous findings from our group for cells grown under topographic guidance (16, 17), as well as results by others, e.g., up-regulated gap junction coupling under cyclic mechanical stretch in neonatal rat cardiomyocyte cultures (27).

Hypertrophic phenotype solely by topographic guidance

These somewhat expected structural changes in topographically guided tissue were accompanied by fundamental cellular reprogramming toward a hypertrophic state (Fig. 3). Increased cell size was seen in topographically guided samples (Fig. 3A), along with a striking 2-fold increase in the percentage of binucleated cells (from 20 to 42% at d 7 in culture; Fig. 3B). Cellular binucleation indicates acytokinetic mitosis; in cardiomyocytes, it occurs during the early postnatal transition from hyperplastic to hypertrophic growth (d 4 to 21 in rodents; ref. 28). It typically signifies increased DNA synthesis per cell, as seen in physiological growth, but it has also been linked to increased metabolic demands and hypertrophic stress in general. In adult humans, increased percentage of binucleated atrial and ventricular myocytes has been reported in cardiomyopathic hearts and in postmyocardial infarction (29).

Furthermore, notably, the secretion of ANP—a widely used clinical marker of hypertrophy—was significantly increased. The difference was evident as soon as 3 h after baselining/resetting and culminated at the 24-h time point in >6 times greater ANP release compared to controls (Fig. 3C). On the basis of analysis of the release time course, this could be attributed to faster ANP secretion kinetics (different slope in Fig. 3C, inset) in the anisotropic samples. The increased secretion of ANP in topographically guided tissue was matched by substantial up-regulation at the mRNA level. The gene expression profile of other hypertrophy markers was also consistent with prior work, including an increase in expression of α-skeletal actin, and a switch in MHC from the α to the β isoforms (Fig. 3D).

To put these changes into perspective, we compared our ANP data to other published in vitro and in situ models of cardiac hypertrophy (Fig. 3E). The increase in ANP mRNA in our topographically guided cardiac syncytium (without external stimulation) was, surprisingly, greater than induced by active stress perturbations, e.g., persistent rapid pacing (13), phenylephrine stimulation (14), or cyclic mechanical stretch of plane-grown cell cultures (12); see also Supplemental Table S1 (30–35), summarizing in vitro data. Notably, the expression of ANP in our in vitro model was within the wide range of values (2.1- to 47-fold increase) reported during hypertrophy in situ (36–38). We note that caution should be used when comparing data obtained in different laboratories, under different experimental conditions in Fig. 3E and the compiled tables (including differences in isolation procedures, culture medium, adhesion-promoting ECM proteins, and presence or absence of serum).

Electrophysiological changes in hypertrophy by topographic guidance

A myriad of functional electrophysiological changes accompany hypertrophy (9). Previously, we have shown that topographic guidance in myocyte cultures resulted in prolonged APD and CTD (example traces in Fig. 4B), increased CV and wavelength along the axis of cell orientation, and enhanced spontaneous pacemaking (18, 21). To compare to previously reported in situ data and examine the gene expression changes underlying altered function in this hypertrophy model, we measured mRNA levels of the major ion channels. A distinctly different gene expression profile was uncovered (Fig. 4A), especially for ion channels involved in cardiac repolarization and pacemaking. A significant decrease in the expression of Kv4.3, encoding for the major K+ repolarizing current in rats, Ito, is a consistent finding in various in situ models of hypertrophy, including transgenic mice, aortic banding, and spontaneous and monocrotaline-induced hypertrophy (Supplemental Table S2; refs. 39–44), and is directly linked to APD prolongation (Fig. 4B). In contrast, by specific pharmacological inhibition, we ruled out SACs as a potential cause of APD prolongation in this hypertrophy model (Supplemental Fig. S2). A decrease in L-type Ca2+ current (main isoform Cav1.2), seen here, has also been reported in hypertrophy in situ induced by aortic banding (ref. 45; see Supplemental Table S2). Expression of Kir2.1, responsible for the inward rectifier current IK1, was reduced, consistent with a phenotype of depolarized membrane potential and increased spontaneous pacemaking, as observed previously in transgenic mice (refs. 39, 46; see Supplemental Table S2) and in our previous studies (18). While alterations in the pacemaking current If are a known hypertrophy-linked phenomenon, the underlying molecular changes may be diverse. Increased expression of the main isoform, HCN2, reported here, is ubiquitous in both physiological growth (47) and in pathological hypertrophy (refs. 48–50; see Supplemental Table S2). However, an increase in the HCN2/HCN4 ratio (or decrease in HCN4; Fig. 4A, inset) is more indicative of physiological growth and transition to adult phenotype (47), rather than pathological hypertrophy (see Supplemental Table S2). This finding, along with up-regulation in the SERCa2 pump, brings attention to the limitations of an in vitro system using neonatal cells, where developmental changes will be copresent with pathological response. For an overview comparison of electrophysiological changes to previous in vitro and in situ models, see refs. 51–53 and Supplemental Tables S1 and S2.

Although clear trends in gene expression were present in the pooled data, significant intersample variability made it difficult to separate the isotropic and anisotropic groups using pairs of expression measurements, pairs of physiological recordings, or standard principal component analysis (Supplemental Fig. S2). However, when PLS regression (25, 26) was used to quantify, on a sample-by-sample basis, correlations between gene expression and physiological measurements (APD, CTD, CV, peak Ca2+), visualization in the resulting principal component space revealed a clean separation between the two groups (Fig. 4C). PLS analysis therefore provides convenient means to classify the (vastly heterogeneous) hypertrophic phenotype using both molecular and functional information on a sample-by-sample basis (not pooled data), as demonstrated here for the first time.

Mechanism of hypertrophy development via topographic guidance

The distinct gene expression profile and phenotype for topography guided cardiac syncytium prompt the question: what drives hypertrophy development in the absence of active exogenous stimulation? As an extension of our earlier studies (16, 21), we propose that periodic out-of-plane attachment sites can elicit new cell/tissue arrangement, which controls syncytial behavior in a way to increase mechanical stress for the myocytes, resulting in the reprogramming seen here (Fig. 5A, B). More specifically, by virtue of having access to out-of-plane localized attachment sites (smaller area, A) in the topographically guided cell cultures, the myocytes are likely to experience higher mechanical stress (σ) compared to plane-grown controls for the same force (F), based on simple σ considerations (Fig. 5A). Moreover, cells grown in plane contract against compliant neighboring cells (same Young modulus), whereas myocytes grown on the grooved surfaces are likely to experience higher reaction forces against the stiffer PDMS scaffolding. This proposed mode of attachment was confirmed in 3-D reconstructions of cytoskeletal images from reflectance confocal imaging (Fig. 5B), revealing “hanging” cells with out-of-plane attachments on the grooved scaffolding.

Self-organization of cardiac syncytium in plane results in isotropic properties without individual cell shape control. With provided linear grooves and peaks, spaced 80–150 μm apart, there are two possible extreme cell layouts: across-groove growth would optimize force development under isometric contractions, while along-groove growth would maximize displacement at lower forces developed (Fig. 5C). Self-organized cell configuration in our studies followed the grooves under an angle, forming bipennate (fishbone-like) patterns around the scaffold peaks (16, 17), reminiscent of some native muscle fiber arrangements, and likely a result of optimization between force and displacement. These bipennate structures elicited corresponding maps of spatial displacement during spontaneous myocyte contractions, with antiphase displacements on opposite sides of the peaks (quantified by digital cross-correlation analysis; Fig. 5D) and overall stronger contractions compared to controls (17).

We proceeded to test the hypothesis that topography-facilitated mechanical stress is the key trophic signal. Active uncoupling of excitation and contraction using either the myosin ATPase inhibitor BDM or the L-type Ca2+ channel blocker Nif completely eliminated the increase in ANP secretion, and equalized ANP levels between anisotropic samples and isotropic controls (Fig. 5E). In particular, inhibition of ANP release by the BDM-mediated disruption of myofilament action points to the essential role that mechanical contraction has in this system. The periodicity of the self-sustained contractions was most likely fueled by up-regulated spontaneous pacemaking, as suggested in our previous study (21) and confirmed by the gene expression profile here (Fig. 4A).

Our mechanistic explanation of how topographic guidance of cardiomyocyte assemblies can result in a robust hypertrophic phenotype, outlined here (Fig. 5) and in previous work (16, 21), focuses on the altered mode of cell attachment, the subsequent increased reaction forces, and increased biomechanical stresses experienced by the cells in this new cell arrangement. We believe that traditional cell culture on planar surfaces lacks these key structural mediators of trophic signals, even when the latter are actively (externally) provided. In contrast, the structure-based hypertrophy model reported here is self-contained—it relies on self-organization and enhanced spontaneous pacemaking to reach a hypertrophic phenotype. Pacemaking and contractile activity are facilitated by the increased stresses (due to attachment) and the altered electrotonus.

Reversal of hypertrophy by exogenous natriuretic peptides

Under increased biomechanical stress and ensuing hypertrophy, myocardial adaptation occurs with complex neuroendocrine changes. It is well documented in clinical studies that both ANP and BNP are positively correlated with the degree of cardiac dysfunction (54–56). Yet ANP and BNP are also negative regulators in hypertrophy and can be used as therapeutic countermeasures (57–61). For example, exogenous BNP is clinically approved and marketed as nesiritide for patients with acutely decompensated congestive heart failure, while ANP (carperitide) is under trials for treatment after myocardial infarction.

We sought to determine whether exogenous natriuretic peptides could have a direct (nonsystemic) effect in our topography-facilitated model of hypertrophy. Indeed, exogenous treatment for 24 h with 100 nM ANP (an order-of-magnitude higher dose than intrinsic release in hypertrophic samples) surprisingly reduced cell size in anisotropic samples, albeit treated samples remained significantly different from isotropic controls (Fig. 6A). The proportion of binucleated cells did not change with treatment. Furthermore, exogenous ANP treatment elicited electrophysiological changes in APD and CTD in direction toward the control phenotype (Fig. 6B). BNP also recovered APD and CTD, but to a lesser extent. Exogenous ANP fully or partially reversed the expression of genetic markers of hypertrophy (ACTA1) and ion channel genes (Kv4.3, Kir2.1, Cav1.2, HCN2, and HCN4; Fig. 6C). In our in vitro system, with optimal diffusion conditions and surface-to-volume area for the action of exogenous agents, ANP was able to impressively affect cell size, gene expression, and function after only 24 h of treatment, where all changes were in a direction of reversal of the hypertrophic phenotype. PLS analysis used as a classifier (Fig. 6C, inset) revealed that ANP treatment “shifted” samples close to the separatrix in the principal component space, when gene expression and function were considered. Our results strongly suggest that these natriuretic peptides are potent not only at the systemic level but also exert direct effects on the myocardium and thus highlight the potential of natriuretic peptides as local negative regulators in myocardial hypertrophy.

CONCLUSIONS

A simple manipulation of the microenvironment in this study (providing periodic out-of-plane cell attachment points) induced a multitude of changes guiding myocyte self-assembly and function toward a new (hypertrophic) phenotype, which previously has been achieved only through active external stimulation (12–14). The new and surprising finding here is that this subtle guidance of cell arrangement was found to be equivalent or even more potent in creating hypertrophic phenotype than active external electrical, mechanical, or chemical stimulation (at least as measured by ANP mRNA levels, Fig. 3E). Furthermore, this in vitro model yielded comparable fold increase in ANP expression to values reported in situ (36–38).

In vivo, structural changes typically accompany the altered signaling and biomechanical milieu seen in hypertrophy, and thus it is important to recognize their essential role as independent contributor to the development of a hypertrophic phenotype. This clear demonstration of the structure-function liaison in cellular reprogramming for actively contracting cardiac syncytium is not implausible in the context of the diseased heart. Damaged regions, e.g., myocardial infarction zones, present stiffer attachment points for neighboring functional myocytes and may resemble the scenario of hypertrophic changes shown here. Our novel in vitro model of cardiac hypertrophy, relying exclusively on self-organization and emergent syncytial behavior, provides a simple test bed for relaying gene expression changes to specific functional parameters, as well as for development of negative regulators and antiarrhythmic agents in cardiac hypertrophy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Zhiheng Jia and Jacqueline Gunther for help with some experiments.

This work was supported by grants from the American Heart Association (0430307N), the National Science Foundation (BES-0503336, 0235467T, and T2390172), and the National Institutes of Health (GM071558).

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

REFERENCES

- 1. Engler A. J., Sen S., Sweeney H. L., Discher D. E. (2006) Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell 126, 677–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rosenberg S. S., Kelland E. E., Tokar E., De la Torre A. R., Chan J. R. (2008) The geometric and spatial constraints of the microenvironment induce oligodendrocyte differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 14662–14667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chen C. S., Mrksich M., Huang S., Whitesides G. M., Ingber D. E. (1997) Geometric control of cell life and death. Science 276, 1425–1428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Geiger B. (2001) Cell biology. Encounters in space. Science 294, 1661–1663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Folch A., Toner M. (2000) Microengineering of cellular interactions. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2, 227–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Balaban N. Q., Schwarz U. S., Riveline D., Goichberg P., Tzur G., Sabanay I., Mahalu D., Safran S., Bershadsky A., Addadi L., Geiger B. (2001) Force and focal adhesion assembly: a close relationship studied using elastic micropatterned substrates. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 466–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Swynghedauw B. (1999) Molecular mechanisms of myocardial remodeling. Physiol. Rev. 79, 215–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hardt S. E., Sadoshima J. (2004) Negative regulators of cardiac hypertrophy. Cardiovasc. Res. 63, 500–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tomaselli G. F., Marban E. (1999) Electrophysiological remodeling in hypertrophy and heart failure. Cardiovasc. Res. 42, 270–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hill J. A. (2003) Electrical remodeling in cardiac hypertrophy. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 13, 316–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wolk R. (2000) Arrhythmogenic mechanisms in left ventricular hypertrophy. Europace 2, 216–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cadre B. M., Qi M., Eble D. M., Shannon T. R., Bers D. M., Samarel A. M. (1998) Cyclic stretch down-regulates calcium transporter gene expression in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 30, 2247–2259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McDonough P. M., Glembotski C. C. (1992) Induction of atrial natriuretic factor and myosin light chain-2 gene expression in cultured ventricular myocytes by electrical stimulation of contraction. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 11665–11668 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zobel C., Rana O. R., Saygili E., Bolck B., Diedrichs H., Reuter H., Frank K., Muller-Ehmsen J., Pfitzer G., Schwinger R. H. (2007) Mechanisms of Ca2+-dependent calcineurin activation in mechanical stretch-induced hypertrophy. Cardiology 107, 281–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Horio T., Nishikimi T., Yoshihara F., Matsuo H., Takishita S., Kangawa K. (2000) Inhibitory regulation of hypertrophy by endogenous atrial natriuretic peptide in cultured cardiac myocytes. Hypertension 35, 19–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Entcheva E., Bien H. (2003) Tension development and nuclear eccentricity in topographically controlled cardiac syncytium. J. Biomed. Microdev. 5, 163–168 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bien H., Yin L., Entcheva E. (2003) Cardiac cell networks on elastic microgrooved scaffolds. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Mag. 22, 108–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yin L., Bien H., Entcheva E. (2004) Scaffold topography alters intracellular calcium dynamics in cultured cardiomyocyte networks. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 287, H1276–H1285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Entcheva E., Bien H. (2005) Acoustic micromachining of three-dimensional surfaces for biological applications. Lab Chip 5, 179–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dunn A. K., Smithpeter C., Welch A. J., Richards-Kortum R. (1996) Sources of contrast in confocal reflectance imaging. Applied Optics 35, 3441–3446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chung C. Y., Bien H., Entcheva E. (2007) The role of cardiac tissue alignment in modulating electrical function. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 18, 1323–1329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bien H., Yin L., Entcheva E. (2006) Calcium instabilities in mammalian cardiomyocyte networks. Biophys. J. 90, 2628–2640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bay B. K. (1995) Texture correlation: a method for the measurement of detailed strain distributions within trabecular bone. J. Orthop. Res. 13, 258–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lau Y. H., Braun M., Hutton B. F. (2001) Non-rigid image registration using a median-filtered coarse-to-fine displacement field and a symmetric correlation ratio. Phys. Med. Biol. 46, 1297–1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sobie E. A. (2009) Parameter sensitivity analysis in electrophysiological models using multivariable regression. Biophys. J. 96, 1264–1274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Geladi P., Kowalski B. R. (1986) Partial least-squares regression: a tutorial. Analyt. Chim. Acta 185, 1–17 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhuang J., Yamada K. A., Saffitz J. E., Kleber A. G. (2000) Pulsatile stretch remodels cell-to-cell communication in cultured myocytes. Circ. Res. 87, 316–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Anversa P., Olivetti G., Loud A. V. (1980) Morphometric study of early postnatal development in the left and right ventricular myocardium of the rat. I. Hypertrophy, hyperplasia, and binucleation of myocytes. Circ. Res. 46, 495–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ahuja P., Sdek P., MacLellan W. R. (2007) Cardiac myocyte cell cycle control in development, disease, and regeneration. Physiol. Rev. 87, 521–544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lalevee N., Rebsamen M. C., Barrere-Lemaire S., Perrier E., Nargeot J., Benitah J. P., Rossier M. F. (2005) Aldosterone increases T-type calcium channel expression and in vitro beating frequency in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc. Res. 67, 216–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gong N., Bodi I., Zobel C., Schwartz A., Molkentin J. D., Backx P. H. (2006) Calcineurin increases cardiac transient outward K+ currents via transcriptional up-regulation of Kv4.2 channel subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 38498–38506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gaughan J. P., Hefner C. A., Houser S. R. (1998) Electrophysiological properties of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes with alpha-adrenergic-induced hypertrophy. Am. J. Physiol. 275, 577–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Walsh K. B., Sweet J. K., Parks G. E., Long K. J. (2001) Modulation of outward potassium currents in aligned cultures of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes during phorbol ester-induced hypertrophy. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 33, 1233–1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Strait J. B., Samarel A. M. (2000) Isoenzyme-specific protein kinase C and c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation by electrically stimulated contraction of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 32, 1553–1566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Makhlouf A. A., McDermott P. J. (1998) Increased expression of eukaryotic initiation factor 4E during growth of neonatal rat cardiocytes in vitro. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 274, H2133–H2142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Adachi S., Ito H., Ohta Y., Tanaka M., Ishiyama S., Nagata M., Toyozaki T., Hirata Y., Marumo F., Hiroe M. (1995) Distribution of mRNAs for natriuretic peptides in RV hypertrophy after pulmonary arterial banding. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 268, H162–H169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kinnunen P., Taskinen T., Leppaluoto J., Ruskoaho H. (1990) Release of atrial natriuretic peptide from rat myocardium in vitro: effect of minoxidil-induced hypertrophy. Br. J. Pharmacol. 99, 701–708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Koyanagi T., Wong L. Y., Inagaki K., Petrauskene O. V., Mochly-Rosen D. (2008) Alteration of gene expression during progression of hypertension-induced cardiac dysfunction in rats. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 295, H220– H226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bodi I., Muth J. N., Hahn H. S., Petrashevskaya N. N., Rubio M., Koch S. E., Varadi G., Schwartz A. (2003) Electrical remodeling in hearts from a calcium-dependent mouse model of hypertrophy and failure: complex nature of K+ current changes and action potential duration. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 41, 1611–1622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gidh-Jain M., Huang B., Jain P., el-Sherif N. (1996) Differential expression of voltage-gated K+ channel genes in left ventricular remodeled myocardium after experimental myocardial infarction. Circ. Res. 79, 669–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Capuano V., Ruchon Y., Antoine S., Sant M. C., Renaud J. F. (2002) Ventricular hypertrophy induced by mineralocorticoid treatment or aortic stenosis differentially regulates the expression of cardiac K+ channels in the rat. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 237, 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Goltz D., Schultz J. H., Stucke C., Wagner M., Bassalay P., Schwoerer A. P., Ehmke H., Volk T. (2007) Diminished Kv4.2/3 but not KChIP2 levels reduce the cardiac transient outward K+ current in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Cardiovasc. Res. 74, 85–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zhang T. T., Cui B., Dai D. Z. (2004) Downregulation of Kv4.2 and Kv4.3 channel gene expression in right ventricular hypertrophy induced by monocrotaline in rat. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 25, 226–230 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lee J. K., Nishiyama A., Kambe F., Seo H., Takeuchi S., Kamiya K., Kodama I., Toyama J. (1999) Downregulation of voltage-gated K+ channels in rat heart with right ventricular hypertrophy. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 277, H1725–H1731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang Z., Kutschke W., Richardson K. E., Karimi M., Hill J. A. (2001) Electrical remodeling in pressure-overload cardiac hypertrophy: role of calcineurin. Circulation 104, 1657–1663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Domenighetti A. A., Boixel C., Cefai D., Abriel H., Pedrazzini T. (2007) Chronic angiotensin II stimulation in the heart produces an acquired long QT syndrome associated with IK1 potassium current downregulation. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 42, 63–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Shi W., Wymore R., Yu H., Wu J., Wymore R. T., Pan Z., Robinson R. B., Dixon J. E., McKinnon D., Cohen I. S. (1999) Distribution and prevalence of hyperpolarization-activated cation channel (HCN) mRNA expression in cardiac tissues. Circ. Res. 85, e1–e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fernandez-Velasco M., Goren N., Benito G., Blanco-Rivero J., Bosca L., Delgado C. (2003) Regional distribution of hyperpolarization-activated current (If) and hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channel mRNA expression in ventricular cells from control and hypertrophied rat hearts. J. Physiol. 553, 395–405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fernandez-Velasco M., Ruiz-Hurtado G., Delgado C. (2006) I K1 and If in ventricular myocytes isolated from control and hypertrophied rat hearts. Pflügers Arch. 452, 146–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hiramatsu M., Furukawa T., Sawanobori T., Hiraoka M. (2002) Ion channel remodeling in cardiac hypertrophy is prevented by blood pressure reduction without affecting heart weight increase in rats with abdominal aortic banding. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 39, 866–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hesse M., Kondo C. S., Clark R. B., Su L., Allen F. L., Geary-Joo C. T., Kunnathu S., Severson D. L., Nygren A., Giles W. R., Cross J. C. (2007) Dilated cardiomyopathy is associated with reduced expression of the cardiac sodium channel Scn5a. Cardiovasc. Res. 75, 498–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Eghbali M., Deva R., Alioua A., Minosyan T. Y., Ruan H., Wang Y., Toro L., Stefani E. (2005) Molecular and functional signature of heart hypertrophy during pregnancy. Circ. Res. 96, 1208–1216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yasui K., Liu W., Opthof T., Kada K., Lee J. K., Kamiya K., Kodama I. (2001) I(f) current and spontaneous activity in mouse embryonic ventricular myocytes. Circ. Res. 88, 536–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tohse N., Nakaya H., Takeda Y., Kanno M. (1995) Cyclic GMP-mediated inhibition of L-type Ca2+ channel activity by human natriuretic peptide in rabbit heart cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 114, 1076–1082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yoshizumi M., Houchi H., Tsuchiya K., Minakuchi K., Horike K., Kitagawa T., Katoh I., Tamaki T. (1997) Atrial natriuretic peptide stimulates Na+-dependent Ca2+ efflux from freshly isolated adult rat cardiomyocytes. FEBS Lett. 419, 255–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kecskemeti V., Pacher P., Pankucsi C., Nanasi P. (1996) Comparative study of cardiac electrophysiological effects of atrial natriuretic peptide. Mol. Cell Biochem. 160–161, 53–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. McGrath M. F., de Bold M. L., de Bold A. J. (2005) The endocrine function of the heart. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 16, 469–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kitashiro S., Sugiura T., Takayama Y., Tsuka Y., Izuoka T., Tokunaga S., Iwasaka T. (1999) Long-term administration of atrial natriuretic peptide in patients with acute heart failure. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 33, 948–952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Suwa M., Seino Y., Nomachi Y., Matsuki S., Funahashi K. (2005) Multicenter prospective investigation on efficacy and safety of carperitide for acute heart failure in the ‘real world’ of therapy. Circ. J. 69, 283–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hayashi M., Tsutamoto T., Wada A., Maeda K., Mabuchi N., Tsutsui T., Horie H., Ohnishi M., Kinoshita M. (2001) Intravenous atrial natriuretic peptide prevents left ventricular remodeling in patients with first anterior acute myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 37, 1820–1826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kuga H., Ogawa K., Oida A., Taguchi I., Nakatsugawa M., Hoshi T., Sugimura H., Abe S., Kaneko N. (2003) Administration of atrial natriuretic peptide attenuates reperfusion phenomena and preserves left ventricular regional wall motion after direct coronary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Circ. J. 67, 443–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.