Abstract

Background: Patients’ perspectives provide valuable information on quality of care. This study evaluates the feasibility and validity of Internet administration of Service Satisfaction Scale for Cancer Care (SCA) to assess patient satisfaction with outcome, practitioner manner/skill, information, and waiting/access.

Patients and methods: Primary data collected from November 2007 to April 2008. Patients receiving cancer care within 1 year were recruited from oncology, surgery, and radiation clinics at a tertiary care hospital. An Internet-based version of the 16-item SCA was developed. Participants were randomised to Internet SCA followed by paper SCA 2 weeks later or vice versa. Seven-point Likert scale responses were converted to a 0–100 scale (minimum–maximum satisfaction). Response distribution, Cronbach’s alpha, and test–retest correlations were calculated.

Results: Among 122 consenting participants, 78 responded to initial SCA. Mean satisfaction scores for paper/Internet were 91/90 (outcome), 95/94 (practitioner manner/skill), 89/90 (information), and 86/86 (waiting/access). Response rate and item missingness were similar for Internet and paper. Except for practitioner manner/skill, test–retest correlations were robust r = 0.77 (outcome), 0.74 (information), and 0.75 (waiting/access) (all P < 0.001).

Conclusions: Internet SCA administration is a feasible and a valid measurement of cancer care satisfaction for a wide range of cancer diagnoses, treatment modalities, and clinic settings.

Keywords: health care delivery, Internet survey, oncology, patient satisfaction

background

Despite advances in cancer detection and treatment, many patients perceive deficiencies in cancer care quality [1–4], defined as ‘the degree to which health services for individuals or populations increase the likelihood of desired health outcomes’ [5, 6]. Although cancer care quality can be evaluated from multiple perspectives (patient, provider, insurer, etc.), patients have been proposed as the ultimate arbiter of care quality [7]. Patients’ perspectives on cancer care processes and outcomes provide unique and valuable information about the quality of care. However, cancer care quality assessments generally depend on medical claims data or medical records abstraction and do not directly assess the cancer care from the patient’s perspective [8].

The three components of health care satisfaction are satisfaction with (i) structure (e.g. organisation, accessibility), (ii) process (e.g. technical and interpersonal competence of the provider), and (iii) outcome (e.g. satisfaction with overall perceived maintenance of health) [9]. However, most previous assessments of cancer care patient satisfaction focus only on health care structure and process [10–19].

We previously developed a novel instrument, the Service Satisfaction Scale for Cancer Care (SCA), to evaluate all three dimensions of patient satisfaction with cancer care (process, structure, and outcome) and validated it in a sample of urological cancer survivors and their spouse partners [20]. The SCA consists of 16 items and is derived from a factor-based reduced form of the Services Satisfaction Scale (SSS-30) [21, 22]. The SSS-30 scale distributions show lower ceiling effects and less skew than a competing satisfaction measure, the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8 [22]. Developed as a self-reported paper instrument, the SCA evaluates patient satisfaction in four care domains on a 7-point Likert scale: (i) outcome of cancer care, (ii) care provider manner and skill, (iii) information provided about care, and (iv) waiting time/access to care. In a multicentre study of prostate cancer survivorship, the SCA demonstrated that changes in quality of life were significantly associated with patient (and partner) satisfaction with treatment outcome [2]. However, the SCA has not been assessed for patients with nonurological cancers and with alternative modes of survey administration. In the current study, we (i) assessed the feasibility and performance of the SCA for a wide range of cancers and (ii) determined the validity of an Internet-based version of the SCA. Electronic surveys may facilitate efficient data collection, improve the convenience of questionnaire completion [13, 23], and increase item responses [23, 24].

patients and methods

study population and design

We developed an Internet-based version of the SCA using the exact wording and scale of the validated paper version. A secure password-protected Universal Resource Locator [25] was created to allow anonymous survey access. Item responses were recorded via a ‘drop-down’ box, which represented the 7-point Likert scale (from 1 to 7: completely satisfied, very satisfied, somewhat satisfied, mixed, somewhat unsatisfied, very unsatisfied, and completely unsatisfied) (Appendix 1). Responses were stored on a secure Web server accessible only to the study staff. A four-digit subject identification number was used to match paper and Internet survey responses.

With approval from the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) Institutional Review Board, potential participants were identified through a review of online medical records of patients seen by 21 participating providers in medical, surgical, gynaecological, and radiation oncology clinics at BIDMC from November 2007 to April 2008. Providers could decline participation on behalf of individual patients. To confirm eligibility, a research assistant not affiliated with clinics nor involved in patient care approached all consecutive potentially eligible participants for each clinic date. Eligible patients were all English-speaking adults who had completed at least one standard cancer therapy (surgery, chemotherapy, and/or radiation therapy) within the past year for any cancer of any stage. The exclusion criteria were no computer/Internet access outside of the clinic. Active cancer treatment at the time of screening did not qualify as a completed cancer treatment course but was not an exclusion criterion.

Of 254 potential participants approached, 155 met all eligibility criteria. The eligibility status of 10 participants could not be determined and were considered ineligible (Figure 1). After eligibility verification, potential participants were provided a written informed consent form to review and were invited to sign if they wished to participate.

Figure 1.

Participant enrolment flowchart.

*One participant with mutually exclusive responses to all items on the paper and Internet surveys was considered noninformative and was excluded from all analysis.

Consenting participants were randomly assigned to one of two groups. The ‘Internet First’ group was asked to complete the Internet-based survey at home within 2 weeks of study enrolment and was given written instructions to access the survey. Two weeks after completion of the Internet-based survey, a self-administered paper survey was mailed to the subject, with instructions to complete and return the survey by mail within 2 weeks. The ‘Paper First’ group was asked to complete the self-administered paper survey at home within 2 weeks of study enrolment and was given a paper copy of the survey. Upon receipt of the paper survey, instructions for accessing the Internet-based survey at home were mailed to the patient, with a request to complete the Internet-based survey within 2 weeks. Participants were provided a preaddressed and stamped envelope in which to return the paper survey. Participants received a telephone reminder call if the survey was not completed within 2 weeks, a time period associated with higher response rates for health-related quality of life (HRQoL) surveys [26].

measures and statistical analyses

Baseline demographics, cancer diagnosis, cancer stage, and treatment modalities were compared between the two randomised groups. Individual items responses were linearly converted from a 7-item Likert scale to a 0–100 scale (higher scores representing higher satisfaction) for item analysis. For domain analysis, Likert scale raw item scores were summed and averaged to create a raw Likert domain score. The domain score was then linearly converted to a 0–100 linear scale. All available responses were included for item and domain scores except as noted.

The responses of all participants who completed at least one survey were analysed in order to compare the paper and Internet survey responses and to evaluate the internal consistency of each survey version. For each satisfaction domain, only those participants answering >65% of items within the domain were analysed. Participants who did not meet the minimum response criteria for a domain were excluded from analysis for that domain. The mean score and standard deviations for individual items and for each satisfaction domain were calculated separately for (i) paper surveys alone, (ii) Internet surveys alone, and (iii) all surveys. To evaluate the presence of a ceiling effect in the SCA, the percentage of participants scoring the maximum (100) on each item and domain was calculated. In order to evaluate internal consistency, Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for each domain using SAS version 9 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

To assess the validity of the Internet-based SCA, we conducted test–retest analysis for each satisfaction domain for all participants completing both surveys. Intraclass correlation coefficients were calculated and statistical significance was determined by confidence intervals using Fisher’s z transformation. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9 and SigmaPlot software (Systat, San Jose, CA).

One participant with mutually exclusive responses to all items on the paper and Internet surveys was considered noninformative and was excluded from all analysis. In addition, we performed a graphical inspection of the linear regression plots during the test–retest analysis in order to identify participants whose responses changed drastically between the paper and Internet surveys. A single participant identified with disparate responses was included in the overall analysis but was excluded from the exploratory test–retest correlation analysis.

results

study population

Of 122 consenting participants, 78 (64%) completed the initial survey. The mean age (59 years; range 30–80), sex, and race (>90% Caucasian) were well balanced between the two randomised groups (Table 1). Participants were diagnosed with a wide range of cancer types (breast, lung, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, gynaecological, haematological, and skin) and all stages (localised, locally advanced, recurrent, and metastatic) were represented. Although breast and lung cancers were the most common diagnoses in both groups, cancer diagnoses were fairly well balanced between the two groups. More than 50% of participants in each group were undergoing chemotherapy at the time of study participation.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants who completed initial survey (n = 77)

| Demographic items | Internet First % (n) | Paper First % (n) |

| Total | (38)a | (39) |

| Mean age (standard deviation) | 59 (9.2) | 59 (10.1) |

| Female | 58 (22) | 59 (23) |

| % Caucasian | 97.4 (37) | 94.9 (37) |

| Cancer diagnosis | ||

| Breast | 31.6 (12) | 28.2 (11) |

| Lung | 18.4 (7) | 25.6 (10) |

| Gastrointestinalb | 15.8 (6) | 20.5 (8) |

| Kidney | 10.5 (4) | 10.3 (4) |

| Prostate | 10.5 (4) | 5.1 (2) |

| Ovarian | 5.3 (2) | 7.7 (3) |

| Otherc | 7.9 (3) | 2.6 (1) |

| Cancer status | ||

| Localised | 55.3 (21) | 35.9 (14) |

| Locally advanced/advanced | 5.2 (2) | 7.7 (3) |

| Metastatic/recurrent | 39.5 (15) | 56.4 (22) |

| Treatment | ||

| Single modality | ||

| Surgery only | 31.6 (12) | 20.5 (8) |

| Chemotherapy only | 23.7 (9) | 17.9 (7) |

| Multiple modalities | ||

| Surgery ± radiation and/or chemo | 34.2 (15) | 53.8 (21) |

| Radiation and chemotherapy | 10.5 (4) | 7.7 (3) |

One participant with mutually exclusive responses to all items on the paper and Internet surveys was considered noninformative and was excluded from all analysis.

Gastrointestinal cancer: oesophageal, colon, pancreatic, rectal, and cholangiocarcinoma.

Other cancers: melanoma, thymoma, multiple myeloma, and endometria

satisfaction with cancer care

For completed paper and Internet surveys, mean scores for all 16 questions ranged from 82 to 96, on a scale from 1 to 100. The highest mean domain score (paper, Internet) was manner/skill (94, 95), followed by outcome (91, 90), information (89, 90), and waiting/access (86, 86) (Table 2). Each domain score showed internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha ≥0.80), except the Internet survey provider manner/skill and waiting/access to care domains (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.69 and 0.62, respectively).

Table 2.

Comparison of satisfaction with cancer care (SCA) administered on paper versus Internet

| Satisfaction domain question (Q)a | Short description | Mean score (standard deviation) |

Score range |

Cronbach’s alpha |

Intraclass correlationb |

|||||

| Paper | Internet | Paper | Internet | Paper | Internet | Paper | Internet | Both | ||

| Outcome | 91 (10) | 90 (10) | 63–100 | 63–100 | 0.90 | 0.85 | 0.78 | 0.74 | 0.77 | |

| Q1 | Help to deal with cancer | 93 (10) | 88 (15) | 67–100 | 17–100 | |||||

| Q8 | Prevent recurrence/progression | 84 (17) | 84 (18) | 50–100 | 33–100 | |||||

| Q10 | Quality of care | 93 (10) | 94 (9) | 67–100 | 67–100 | |||||

| Q13 | Relieve/prevent symptoms | 89 (13) | 88 (14) | 50–100 | 33–100 | |||||

| Q16 | Overall satisfaction | 92 (11) | 92 (9) | 67–100 | 67–100 | |||||

| Manner/skill | 94 (8) | 95 (7) | 73–100 | 60–100 | 0.87 | 0.69 | 0.48 | 0.65 | 0.55 | |

| Q2 | Professional knowledge | 94 (8) | 95 (13) | 67–100 | 17–100 | |||||

| Q3 | Listening and responding | 93 (10) | 95 (9) | 50–100 | 67–100 | |||||

| Q4 | Personal manner | 93 (11) | 92 (16) | 50–100 | 0–100 | |||||

| Q9 | Confidentiality | 95 (8) | 96 (7) | 67–100 | 83–100 | |||||

| Q14 | Thoroughness | 93 (9) | 95 (8) | 67–100 | 83–100 | |||||

| Information | 89 (11) | 90 (12) | 50–100 | 61–100 | 0.85 | 0.91 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.74 | |

| Q11 | Availability of information | 87 (15) | 87 (14) | 33–100 | 50–100 | |||||

| Q12 | Explanations of treatments | 91 (12) | 92 (11) | 50–100 | 67–100 | |||||

| Q15 | Helpfulness of information | 90 (11) | 90 (13) | 67–100 | 50–100 | |||||

| Waiting/access | 86 (13) | 86 (10) | 44–100 | 61–100 | 0.80 | 0.62 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.74 | |

| Q5 | Lag time after appt request | 88 (15) | 88 (13) | 33–100 | 33–100 | |||||

| Q6 | Wait after arrival | 82 (16) | 82 (14) | 50–100 | 50–100 | |||||

| Q7 | Availability of appt time | 87 (15) | 87 (13) | 33–100 | 50–100 | |||||

Italicized numbers are domain results.

Both = Internet-based and paper SCA (n = 131); paper = paper SCA (n = 70); Internet = Internet-based SCA (n = 61); Appt = Appointment.

See Appendix for details of each satisfaction domain question.

Correlation of paper and Internet survey responses of participants who completed both surveys.

SCA, Service Satisfaction Scale for Cancer Care.

For participants who completed both versions of the survey instrument, test–retest analysis showed significant correlations (r = 0.48–0.78; P < 0.05) in all four satisfaction domains. Outcome, waiting/access, and information domains had similar intraclass correlation levels when evaluated as a group and by subgroup (r = 0.74–0.77) (Table 2). Ordering (Paper First versus Internet First) did not significantly change these results. The manner/skill domain for the Paper First group produced the weakest correlation (r = 0.48; P < 0.05). Graphical inspection of the correlation plots for the Paper First group revealed one subject with a substantial change in response for the manner/skill domain between the two surveys. Exploratory analysis excluding this potential outlier improved the test–retest correlation for this domain (Paper First, r = 0.81, 95% confidence interval = 0.59–0.91 and combined, r = 0.72, 95% confidence interval = 0.56–0.83).

Of 78 participants completing the first version of the survey, 54 (69%) completed the retest survey. The proportion of participants who completed the retest was higher for those who completed the Internet survey first than for those who completed the paper survey first: 32 of 39 (82%) versus 22 of 39 (56%), respectively. The mean time between initial consent and completion of the first survey was 16.7 days (Paper First = 21.5 days and Internet First = 11.9 days). The mean time between completion of the first and second surveys was 26.4 days (Paper First = 30.6 days and Internet First = 23.6 days) (Figure 2).

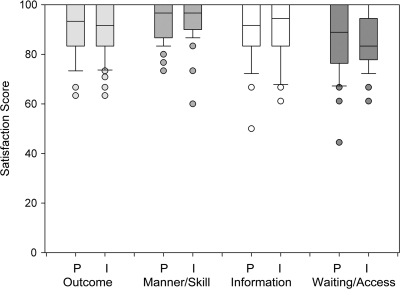

Figure 2.

Comparison of paper (P) versus Internet (I) surveys (all participants)—lower boundary of the box represents 25th percentile—line within the box represents median—upper boundary of the box represents 75th percentile—whiskers above and below the box represent 90th and 10th percentiles, respectively—points represent outliers.

A ceiling effect was apparent for all four domains in both surveys, but a floor effect was not present (Figure 2). The percent of responses at the ceiling were lowest for ‘waiting time at appointment’ (Question 6) for both Internet (23%) and paper (33%) and highest for ‘protected rights of patient’ (Question 9) for both Internet (77.1%) and paper (69%). The average percent of responses at the ceiling was similar in both the Internet and the paper SCA: 56% and 55%, respectively.

The number of missing item responses in paper and Internet surveys was similar and the majority of items had zero missing responses (Table 2; item missingness range = 0–15% per item and overall item missingness = 1% for paper and 1.2% for Internet versions). The proportion of scorable subscales (less than one missing subscale item i) was 97.2% (paper) and 100% (Internet) for outcome, 100% (paper) and 100% (Internet) for practitioner, 100% (paper) and 100% (Internet) for access, and 100% (paper) and 100% (Internet) for information subscales. The highest number of missing responses for a single question was the same for both Internet and paper surveys (‘What is your overall feeling about the effect of your cancer treatment in preventing cancer progression and recurrence?’) (paper = seven missing responses and Internet = nine missing responses) (Table 2 and Figure 2).

conclusions

Our study establishes the feasibility and validity of the SCA for assessment of patient satisfaction with cancer care outcome, process, and structure via paper- or Internet-based administration. The four SCA satisfaction domains demonstrated test–retest reliability, internal consistency, and validity for the paper- and Internet-based version. These findings support the use of the SCA version most appropriate for the study population. To our knowledge, this study is the first to validate an electronic instrument that comprehensively measures satisfaction with cancer care outcome (in addition to cancer care process and structure) for patients with a wide range of tumour types and stages [10–12, 15–19, 27].

The validation results of our study are supported by a meta-analysis demonstrating that electronic and paper administration of patient reported outcome instruments yield equivalent results [10, 28–31]. The only electronic evaluation of satisfaction with cancer care (SEQUS for medical oncology outpatients) only evaluates structure and process but not outcome. The top concern identified by SEQUS [10] (patient waiting times) was also determined to be an area of relative dissatisfaction in our study. However, additional satisfaction with outcomes data from our study places this result in context, potentially informing resource allocation decisions that optimally improve cancer care quality.

The results of our study must be considered in contexts of its limitations. Due to loss of follow-up, 64% of consented patients completed the initial survey and 44% completed both surveys. However, this completion rate is consistent with other evaluations of patient satisfaction with cancer care (50%–100%) [10–12, 14, 16, 17].

The relatively small sample size and the single urban academic institution study population did not permit subset evaluation and may limit generalisability of to other settings. However, the results of our study for a wide range of cancer diagnoses are consistent with a larger paper SCA study of patients with prostate cancer at multiple institutions across the United States [2]. Additionally, due to the test–retest study design for the study hypothesis, patients who were unable to use or access a computer with Internet were excluded. Our results, therefore, may have demographic, socioeconomic, and/or functional status biases. However, others have demonstrated validity of electronic HRQoL surveys for a wide range of patients with varying levels of computer literacy, education, age, sex, and race [13, 28, 32]. In addition, the off-site design was chosen to minimise positive bias associated with on-site surveys [33]. Finally, we designed this study to closely mirror real-life situations of future quality improvement or research situations without on-site computer/Internet access and in-person assistance for respondents.

A ceiling effect was present for both versions of the survey, as commonly seen in patient satisfaction surveys [34–36]. Ceiling effects may reflect prior findings that survey responders have more positive experiences than nonresponders [37] and may obscure the true magnitude of satisfaction differences [35]. However, the majority of responses for all domains in both surveys were less than the maximum score, indicating that the survey instrument can discriminate the level of patient satisfaction.

On average, the Paper First group had a longer time interval between initial consent and completion of the first survey and between the completion of the first and second surveys than the Internet First group. This difference may be due to the longer mailing times required for returning the paper survey and receiving Internet survey instructions and may account for the higher attrition rate for the Paper First group. A previous study found higher response rates among cancer patients who received a satisfaction survey more quickly [26]. Although the completion time interval difference may have affected survey values, the presence of robust test–retest correlations suggests minimal effect on validity testing.

To assess for potential response bias, we performed exploratory chart reviews of patients with missing responses for the question with the highest number of missing responses (n = 13): ‘What is your overall feeling about the effect of your cancer treatment in preventing cancer progression and recurrence?’ Participants with missing responses tended to be undergoing active cancer treatment (n = 7), have metastatic or recurrent cancer (n = 7), and/or symptoms secondary to cancer or cancer treatment complications (n = 5). These may be situations in which nonresponders felt uncertain about their prognosis.

As a validation study, this study did not assess patient preferences for survey version nor the impact of the Internet-based instrument on practice patterns. Several studies demonstrate that electronic collection of patient reported data facilitates real-time feedback of survey results to clinicians and may confer several advantages [29, 34, 38, 39]: (i) increased clinician inquiries about HRQoL issues [34, 38], (ii) improved clinician-perceived communication with patients [38], and (iii) increased clinician-perceived tracking of HRQoL changes over time [38].

Patient satisfaction may vary due to factors beyond the current care provider’s control, including the limitations of current cancer treatments [27, 36, 40–43]. Further study is also needed on how patient satisfaction data affects the patient–provider relationship, particularly in cancer care where both the provider and the patient may be disappointed with the effectiveness of current therapies. Currently, some health payers provide financial incentives for cancer care quality improvement based on patient satisfaction data [44]. Assessment of satisfaction with outcome, such as provided by the SCA, may highlight important gaps in quality, including those due to socioeconomic disparities [1]. However, the effect of these financial incentives on patient outcome is unknown. Cancer care quality assessment instruments that assess satisfaction with outcome may be important to answer these questions and generate new hypotheses.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that the paper and Internet-based versions of the SCA provide valid measures of patient satisfaction in multiple domains of cancer care, including treatment outcome, and may be useful for evaluating cancer care quality for a variety of cancer diagnoses, clinical settings, and treatment modalities. Multiple options for patient satisfaction survey completion (self-completion with a paper or Internet version at home or in the clinic, in-person completion, or over the telephone) may enhance patient response rates and diversity. The SCA may help improve cancer care quality by placing other metrics of patient satisfaction in context with cancer treatment outcome.

funding

National Institutes of Health (R01 CA95662) to MS and Program in Cancer Outcomes Research Training (5R25CA 092203-04) to RM and the Department of Medicine, BIDMC, and the Clinical Investigator Training Program: BIDMC—Harvard/MIT Health Sciences and Technology, in collaboration with Pfizer Inc. and Merck & Co to RM.

disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, writing of this manuscript, or the decision to submit for publication. We would like to thank the patients at BIDMC and the participating clinicians (in alphabetical order): Mary Buss, Mark Callery, Steven Come, Daniel Costa, Malcolm DeCamp, Sidharta Ganghadharan, Michael Goldstein, Sanjay Jain, Michael Kent, Tara Kent, Young B. Kim, Corrine Zarwan, Anand Mahadevan, David McDermott, Deborah Nagle, Elena Nedea, Lowell Schnipper, Susan Schumer, Nadine Tung, and Andrew Wagner. In addition, we gratefully acknowledge study support provided by Gerardina Bueti, Kuan-Chi Lai and Jodi Mechaber.

appendix 1. SCA survey questions

What is your overall feeling about the …

| 1. | Effect of health care services in helping you deal with your cancer and maintain your well being? |

| 2. | Professional knowledge and competence of your main cancer practitioner(s)? |

| 3. | Ability of your main cancer practitioner(s) to listen and respond to your concerns or problems? |

| 4. | Personal manner of the main cancer practitioner(s) seen? |

| 5. | Waiting time between asking to be seen or treated and the appointment given? |

| 6. | Waiting time when you come for an appointment? |

| 7. | Availability of appointment times that fit your schedule? |

| 8. | Effect of cancer treatment in preventing cancer progression or recurrence? |

| 9. | How well your confidentiality and rights as an individual have been protected? |

| 10. | Quality of cancer care you have received? |

| 11. | Availability of information on how to get the most out of the cancer care and related services? |

| 12. | Explanations of specific procedures and treatment approaches used? |

| 13. | Effect of services in helping relieve symptoms of reduce problems? |

| 14. | Thoroughness of the main cancer practitioner(s) you have seen? |

| 15. | Helpfulness of the information provided about your cancer and its treatment? |

| 16. | In an overall general sense, how satisfied are you with the cancer treatment you have received? |

References

- 1.Ayanian JZ, Zaslavsky AM, Guadagnoli E, et al. Patients' perceptions of quality of care for colorectal cancer by race, ethnicity, and language. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(27):6576–6586. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(12):1250–1261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hewitt ME, Simone JV. National Cancer Policy Board. Ensuring Quality Cancer Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bickell NA, LePar F, Wang JJ, Leventhal H. Lost opportunities: physicians' reasons and disparities in breast cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(18):2516–2521. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.5539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute of Medicine (U.S.) Division of Health Care Services, Lohr KN, Institute of Medicine. Committee to Design a Strategy for Quality Review and Assurance in Medicare. United States. Health Care Financing Administration. Medicare: A Strategy for Quality Assurance. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lohr KN, Schroeder SA. A strategy for quality assurance in Medicare. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(10):707–712. doi: 10.1056/nejm199003083221031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1966;44(3) Suppl:166–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dennison CR. The role of patient-reported outcomes in evaluating the quality of oncology care. Am J Manag Care. 2002;8(18) Suppl:580S–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cleary PD, McNeil BJ. Patient satisfaction as an indicator of quality care. Inquiry. 1988;25(1):25–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gourdji I, McVey L, Loiselle C. Patients' satisfaction and importance ratings of quality in an outpatient oncology center. J Nurs Care Qual. 2003;18(1):43–55. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200301000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagedoorn M, Uijl SG, Van Sonderen E, et al. Structure and reliability of Ware's Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire III: patients' satisfaction with oncological care in the Netherlands. Med Care. 2003;41(2):254–263. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000044904.70286.B4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bredart A, Bottomley A, Blazeby JM, et al. An international prospective study of the EORTC cancer in-patient satisfaction with care measure (EORTC IN-PATSAT32) Eur J Cancer. 2005;41(14):2120–2131. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bliven BD, Kaufman SE, Spertus JA. Electronic collection of health-related quality of life data: validity, time benefits, and patient preference. Qual Life Res. 2001;10(1):15–22. doi: 10.1023/a:1016740312904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bredart A, Razavi D, Robertson C, et al. A comprehensive assessment of satisfaction with care: preliminary psychometric analysis in French, Polish, Swedish and Italian oncology patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;43(3):243–252. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(00)00165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lubeck DP, Litwin MS, Henning JM, et al. An instrument to measure patient satisfaction with healthcare in an observational database: results of a validation study using data from CaPSURE. Am J Manag Care. 2000;6(1):70–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loblaw DA, Bezjak A, Bunston T. Development and testing of a visit-specific patient satisfaction questionnaire: the Princess Margaret Hospital Satisfaction With Doctor Questionnaire. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(6):1931–1938. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.6.1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Defossez G, Mathoulin-Pelissier S, Ingrand I, et al. Satisfaction with care among patients with non-metastatic breast cancer: development and first steps of validation of the REPERES-60 questionnaire. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:129. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-7-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schoen RE, Weissfeld JL, Bowen NJ, et al. Patient satisfaction with screening flexible sigmoidoscopy. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(12):1790–1796. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.12.1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiggers JH, Donovan KO, Redman S, Sanson-Fisher RW. Cancer patient satisfaction with care. Cancer. 1990;66(3):610–616. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900801)66:3<610::aid-cncr2820660335>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shah NL, Dunn R, Greenfield TK, et al. Development and validation of a novel instrument to measure patient satisfaction in multiple dimensions of urological cancer care quality. J Urol. 2003;169(Suppl):11. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenfield TK, Attkisson CC. Service Satisfaction Scale–30 (SSS-30) In: Rush AJ Jr, Pincus HA, First MB, et al., editors. Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. pp. 188–191. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenfield TK, Attkisson CC. The UCSF Client Satisfaction Scales: II. The Service Satisfaction Scale-30. In: Maruish M, editor. Psychological Testing: Treatment Planning and Outcome Assessment. 3rd edition. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2004. pp. 813–837. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryan JM, Corry JR, Attewell R, Smithson MJ. A comparison of an electronic version of the SF-36 General Health Questionnaire to the standard paper version. Qual Life Res. 2002;11(1):19–26. doi: 10.1023/a:1014415709997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kongsved SM, Basnov M, Holm-Christensen K, Hjollund NH. Response rate and completeness of questionnaires: a randomized study of Internet versus paper-and-pencil versions. J Med Internet Res. 2007;9(3):e25. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9.3.e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanda M, Greenfield T. Satisfaction with cancer care-patient. 2003 https://pm.caregroup.org/survey/bidmc/satisfaction.asp (21 April 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bredart A, Razavi D, Robertson C, et al. Timing of patient satisfaction assessment: effect on questionnaire acceptability, completeness of data, reliability and variability of scores. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;46(2):131–136. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00152-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brennan J. Adjustment to cancer—coping or personal transition? Psychooncology. 2001;10(1):1–18. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200101/02)10:1<1::aid-pon484>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gwaltney CJ, Shields AL, Shiffman S. Equivalence of electronic and paper-and-pencil administration of patient-reported outcome measures: a meta-analytic review. Value Health. 2008;11(2):322–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Velikova G, Wright EP, Smith AB, et al. Automated collection of quality-of-life data: a comparison of paper and computer touch-screen questionnaires. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(3):998–1007. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.3.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taenzer PA, Speca M, Atkinson MJ, et al. Computerized quality-of-life screening in an oncology clinic. Cancer Pract. 1997;5(3):168–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abernethy AP, Herndon JE, 2nd, Wheeler JL, et al. Improving health care efficiency and quality using tablet personal computers to collect research-quality, patient-reported data. Health Serv Res. 2008;43(6):1975–1991. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00887.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kleinman L, Leidy NK, Crawley J, et al. A comparative trial of paper-and-pencil versus computer administration of the Quality of Life in Reflux and Dyspepsia (QOLRAD) questionnaire. Med Care. 2001;39(2):181–189. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200102000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burroughs TE, Waterman BM, Gilin D, et al. Do on-site patient satisfaction surveys bias results? Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2005;31(3):158–166. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(05)31021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taenzer P, Bultz BD, Carlson LE, et al. Impact of computerized quality of life screening on physician behaviour and patient satisfaction in lung cancer outpatients. Psychooncology. 2000;9(3):203–213. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200005/06)9:3<203::aid-pon453>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams B, Coyle J, Healy D. The meaning of patient satisfaction: an explanation of high reported levels. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47(9):1351–1359. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00213-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenthal GE, Shannon SE. The use of patient perceptions in the evaluation of health-care delivery systems. Med Care. 1997;35(11) Suppl:NS58–NS68. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199711001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rubin HR. Patient evaluations of hospital care. A review of the literature. Med Care. 1990;28(9) Suppl:S3–S9. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199009001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Velikova G, Brown JM, Smith AB, Selby PJ. Computer-based quality of life questionnaires may contribute to doctor-patient interactions in oncology. Br J Cancer. 2002;86(1):51–59. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mullen KH, Berry DL, Zierler BK. Computerized symptom and quality-of-life assessment for patients with cancer part II: acceptability and usability. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004;31(5):E84–E89. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.E84-E89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sofaer S, Firminger K. Patient perceptions of the quality of health services. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:513–559. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.050503.153958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sandoval GA, Brown AD, Sullivan T, Green E. Factors that influence cancer patients' overall perceptions of the quality of care. Int J Qual Health Care. 2006;18(4):266–274. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzl014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skarstein J, Dahl AA, Laading J, Fossa SD. 'Patient satisfaction' in hospitalized cancer patients. Acta Oncol. 2002;41(7–8):639–645. doi: 10.1080/028418602321028256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ley P, Bradshaw PW, Kincey JA, Atherton ST. Increasing patients' satisfaction with communications. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1976;15(4):403–413. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1976.tb00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tisnado DM, Rose-Ash DE, Malin JL, et al. Financial incentives for quality in breast cancer care. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(7):457–466. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]