Preface

Over the course of evolution, eukaryote aminoacyl tRNA synthetases progressively added domains and motifs that have no essential connection to aminoacylation reactions. Their accretive addition to virtually all tRNA synthetase correlates with the progressive evolution and complexity of eukaryotes. Based on recent experimental findings focused on a few of these additions, and analysis of the tRNA synthetase proteome, we propose that these additions are markers for synthetase-associated functions beyond translation.

The aminoacylation reaction, which is catalyzed by aminoacyl tRNA synthetases, fuses each amino acid to its cognate tRNA in a reaction that requires amino acid activation through condensation of the amino acid with ATP to form an aminoacyl adenylate. The activated amino acid is then transferred to the 3′ end of the cognate tRNA (Box 1). Because the cognate tRNAs harbour the anticodon triplets of the genetic code, the specific aminoacylations catalyzed by the synthetases establish the rules of the universal genetic code. Thus, tRNA synthetases arose early in evolution, perhaps replacing the activities of ribozymes, the first catalysts of aminoacylations, as the transition was made from the RNA to the protein world.

Box 1. Basic function of aminacyl-tRNA synthetase.

| (1) |

| (2) |

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (aaRSs) provide the first resource for production of proteins. The algorithm of the genetic code is established in this first reaction of protein synthesis. In this reaction, aminoacyl tRNA synthetases catalyze the attachment of amino acids to their cognate tRNAs that bear the triplet anticodons of the code. These enzymes catalyse the attachment of amino acids in a two-step reaction. The amino acid (aa) is first condensed with ATP to form a tightly bound aminoacyl adenylate, and inorganic phosphate (PPi) is released (equation (1)). The activated aminoacyl group is then transferred from the adenylate to the 3′ end of the tRNA to form aa–tRNA. This also releases AMP and the aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (equation (2)). Because of their essential role in protein synthesis, genes encoding aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases appeared when life began1. As a family of 20 enzymes in general (one for each amino acid), aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases are constrained by evolutionary pressure to preserve this essential activity, but they still managed to develop additional functions during evolution.

All synthetases have an aminoacylation domain, which encodes the active site that recognizes the specific amino acid, ATP and the 3′ end of the bound tRNA. On the basis of the architecture of this domain, the enzymes are split into two classes (comprising 10 enzymes each): class I, in which the domain has a Rossmann nucleotide-binding fold; and class II, in which the domain is a seven-stranded β-sheet with flanking α-helices1, 2. These two architectures are thought to have arisen from opposite (that is, complementary) strands of RNA genomes that may have existed in the RNA world and that encoded a class I (strand 1) and a sister class II (complementary strand 2) tRNA synthetase3, 4. The complementary sister synthetases can be modelled to bind simultaneously to opposite sides of the tRNA acceptor stems, thereby covering much of the tRNA5, 6. They could have served, among other possibilities, as chaperones to protect the tRNA substrate from destruction by nucleases and phosphate bond-cleaving metal ions. Apart from the well-conserved catalytic units, many tRNA synthetases made later additions of less-conserved anticodon-binding domains to more efficiently recognize tRNAs.

In addition to the aminoacylation functions, about half of the tRNA synthetases added an editing function, which enables removal of the wrong amino acid from its cognate tRNA7. Those synthetases face a greater challenge to differentiate the cognate versus the non-cognate amino acid (e.g., isoleucine from valine) than the others. This editing function is an important mechanism to prevent mistranslation, during which the wrong amino acid is inserted at a specific codon. For life to thrive, the challenge of preventing mistranslation through mischarging of tRNA had to be overcome. For this reason, the addition of an editing domain to an aminoacylation domain happened prior to the time that the three kingdoms of life diverged from the last universal common ancestor (LUCA), with strong selective pressure ever since to keep both domains throughout evolution8

And yet, over evolution, tRNA synthetases added domains with no apparent connection to their aminoacylation reactions. In this Opinion, we investigate the general logic and purpose of these new domains, especially in eukaryotes. As described below, our analysis shows that these domain additions were accretive and progressive, following the increasing complexity of eukaryotic organisms. We also find that this ensemble and pattern of domain additions was specific to tRNA synthetases. Importantly, a close inspection of the pattern of domain additions shows that the new functions that have been identified for some of these domains were introduced at precise times in evolution and were associated with the appearance of a new biological function (such as a circulatory system). This observation raises the possibility that the domain additions played an important part in expanding the complexity and sophistication of newly emerging organisms.

Annotation of new domains and motifs

With a clear understanding of the essential role and logic of the aminoacylation and editing domains, we were surprised to find that, as the tree of life ascended, tRNA synthetases progressively added domains and sequence motifs that are connected to neither aminoacylation nor editing. Table 1 displays an annotation of both shared domains or motifs (those in more than one synthetase) and unique domains or motifs (those in a specific synthetase) found in the eukaryotic tRNA synthetase proteome. The five shared domains or motifs are structural modules that are similar to those seen in other proteins, such as a specialized version of the helix–turn–helix motif known as the WHEP domain, the oligonucleotide binding fold-containing EMAPII domain that is also found in p43 (an auxiliary factor found in the multi-tRNA synthetase complex of eukaryotes), the leucine-zipper domain, the GST domain and a specialized amino-terminal helix (N-helix)9. These domains were added to specific synthetases as the tree of life ascended from lower to higher eukaryotes. Because WHEP, leucine zipper and GST domains are used for forming complexes with other proteins10, and because the EMAPII domain can function as a cytokine when cleaved from the tRNA synthetase or p43 by binding to a cell surface receptor11, these domain additions are strongly suggestive of an interaction with a partner protein 12–15

Table 1. Summary of domains added to aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases.

Each added sequence was checked by iterative searching the non-redundant database of NCBI using PSIBLAST. Unique, unfamiliar domains are defined when no homologous sequences (E value < 0.005) were found in other aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases after the PSI-BLAST converged. Also, with the exception of PheRS, the eight UNEs are not similar to any in sequence databases of all bacterial or archaeal tRNA synthetases. Furthermore, apart from PheRS and GlnRS, no UNE bears similarity (E value < 0.005) to sequences found in non synthetase proteins. D. melanogaster MetRS has 3 WHEP domains at the C-terminus (InterPro: A1ZBE9), which were not found in the previous reports

| S. cerevisiae | C. elegans | D. melanogaster | D. rerio | H. sapiens | Position in Human tRNA Synthetases | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CysRS | + UNE-C1,2 | + GST | 201–297/664–831, 1–82 | |||

| GlnRS | + UNE-Q | 1–260 | ||||

| ArgRS | + LZ | 5–32/41–64 | ||||

| MetRS | + GST | + LZ, + EMAP II | + GST, + WHEP | 8–218, 844–897 | ||

| ValRS | + GST | 2–218 | ||||

| LeuRS | + UNE-L | 1064–1176 | ||||

| IleRS | + UNE-I | 1065–1266 | ||||

| TrpRS | + WHEP | 8–64 | ||||

| TyrRS | + ELR, + EMAPII | 360–524 | ||||

| GluRS | + GST | + WHEP | GluProRS fuse | 1–178, 749–805/822–878/900–956 | ||

| ProRS | + WHEP | |||||

| HisRS | + WHEP | 3–43 | ||||

| PheRS | + UNE-F | 6–100 | ||||

| AspRS | + N-helix | 6–24 | ||||

| LysRS | + N-helix | 20–40 | ||||

| AsnRS | + UNE-N | 1–99 | ||||

| ThrRS | + UNE-T | 1–80 | ||||

| AlaRS | ||||||

| SerRS | + UNE-S | 461–514 | ||||

| GlyRS | + WHEP | 2–61 | ||||

| MSC p18 | Appear, + GST | 1–154 | ||||

| MSC p38 | Appear, + LZ, + GST | 50–80, 149–319 | ||||

| MSC p43 | Appear, + LZ, + EMAPII | 8–28/38–72, 150–311 | ||||

Unlike the shared domains, the eight unique sequence motifs are specific to only one synthetase. With the exception of PheRS, the eight unique sequence motifs are not similar to any that we could find from searching sequence databases of all bacterial or archaeal tRNA synthetases. In addition, apart from PheRS and GlnRS, their sequence is not similar to those of non-synthetase proteins. We designate these unique motifs as UNE-L, UNE-S and so on, in which the single letter designates the amino acid type of the synthetase that harbours the specific unique domain (so UNE-L is associated with leucyl-tRNA synthetase and UNE-S with seryl-tRNA synthetase). These unique domains and motifs were added to specific tRNA synthetases at distinct points in evolution. Similarly to the shared domains or motifs, UNE domains were grafted onto the canonical synthetase long after the aminoacylation function was established. Importantly, with the exception of MetRS, these domains or motifs were irreversibly retained by the respective tRNA synthetase right until humans evolved.

Connections of new domains to novel functions

Novel functions that are distinct from their role in translation have been identified for a few human tRNA synthetases. Three examples of these functions, which depend on the addition of one or more new domains or motifs, are given below. Many additional examples are anticipated to emerge in the future, as more and more of these new structural units are investigated.

Tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase

Figure 1a traces in evolution the addition of two new sequence and structural elements to tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase (TyrRS). The tripeptide ELR (GluLeuArg) and the EMAPII domain were added at the stage of insects and have been retained ever since. Neither ELR nor EMAPII is found in lower eukaryotic, archaeal or bacterial TyrRSs. Although EMAPII is fused to the carboxyl terminus of the catalytic domain of the tRNA synthetase, ELR is within catalytic domain itself. However, mutations in ELR or ablation of EMAPII had little effect on the aminoacylation activity16–18. These observations suggest that the additions of ELR and EMAPII to higher eukaryotic TyrRSs are associated with new functions that are not related to aminoacylation. Furthermore, because the two additions occurred simultaneously, each might be needed for the development of the same new function.

Figure 1. Domain additions to specific higher eukaryote aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases.

a | Temporal appearance of ELR motif and EMAPII domain, which confer and regulate cytokine activities of TyrRSs. ELR and EMAPII were added simultaneously to TyrRSs, starting from insects. b | Temporal appearance of WHEP domain for TrpRSs. WHEP domain was found to regulate the angiostatic function of human TrpRS. c | Temporal appearance of WHEP domain for GluRS–ProRSs. Initially separated, GluRS and ProRS gained WHEP domains in nematodes and fused into one protein that is linked by a WHEP domain in higher eukaryotes.

Indeed, both additions are known to work in concert in receptor-mediated signalling pathways that are associated with angiogenesis19. ELR is the signature sequence of CXC chemokines that have angiogenic activity by binding CXC-chemokine receptor 1 (CXCR1) or CXCR220. EMAPII binds α5β1 integrin receptor on the surface of endothelial cells and inhibits integrin-dependent cell adhesion and spreading. Furthermore, following internalization by endothelial cells, EMAPII inhibits Hif1α-regulated angiogenesis21.

Two high resolution crystal structures of human TyrRS suggested an autoinhibitory structure in which the EMAPII domain of TyrRS blocks ELR, making it inaccessible to its receptors on the cell surface and thereby shield/mute the embedded angiogenic activity of TyrRS22, 23. After secretion of TyrRS, removal of EMAPII by proteolytic cleavage unmasks the ELR tripeptide motif. Thus, the two additions — a new domain (EMAPII) and a new tripeptide motif (ELR) — to TyrRS are connected to the same function.

Tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase

Figure 1b traces the addition of the WHEP domain to tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase (TrpRS). The new domain was added at the stage of chordates and was retained ever since. This domain has been found to have a regulatory function, as it inhibits the activation of the angiostatic activity of TrpRS that evolved in higher eukaryotes (TrpRS is strongly upregulated by interferon-γ (IFNγ), along with other angiostatic factors such as MIG and IP1024). Indeed, removal of WHEP (by alternative splicing or proteolysis) activates TrpRS as a potent angiostatic factor25–27, which then binds to VE-cadherin (a protein involved in endothelial cell adhesion and consequently angiogenesis)28. Strikingly, two protruding Trp side chains near the N terminus of VE-cadherin fit into the adenylate pocket (made up of Trp and AMP subpockets) of TrpRS, thereby inducing VE-cadherin– TrpRS complex formation29. High-resolution crystal structural analysis of human TrpRS showed that the position of the WHEP domain makes the subpockets sterically inaccessible to VE-cadherin while still allowing entry of the small molecule substrates (Trp and AMP) so as not to interfere with aminoacylation30. Similarly to TyrRS, at least one role for the new added domain is to regulate the accessibility of a signalling motif within the synthetase that interacts with its cognate receptor.

Glu–Pro fusion tRNA synthetase

A third example, which also involves a WHEP domain, is the unusual GluRS–ProRS (EPRS) fusion enzyme. In this case, the WHEP domain serves as a linker to join the two synthetases. The WHEP domain first appeared in GluRS and ProRS in nematodes and was retained (in EPRS) ever since (Fig. 1c)31. EPRS is part of the multi-tRNA synthetase complex (MSC) found in higher eukaryotes32. Earlier work showed that, after stimulation with IFNγ, EPRS is phosphorylated and released from the MSC, and then becomes part of the IFNγ-activated inhibitor of translation (GAIT) complex. It subsequently silences translation by binding (mediated by WHEP) to a stem loop structure (known as GAIT element) in the 3′-untranslated region of one or more mRNAs that function in pathways for inflammation and iron homeostasis33. Thus, EPRS is linked to the inflammatory response. EPRS is also thought to repress the translation of proteins involved in other signalling pathways that are sensitive to signalling from IFNγ and hypoxia, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). This silencing is enabled by the RNA and protein interactions of the WHEP domain34, 35.

New domains and evolution

The three examples of TyrRS, TrpRS and EPRS are consistent with the idea that new domains fused to tRNA synthetases are markers for new functions for these proteins. Other added domains have been identified, and their appearance correlates with the emergence of new biological functions.

More general appearance of new domains

To investigate the full extent of the elaboration of these markers, Figure 2 shows the appearance at specific points in evolution of all of the new domains and motifs that have been joined to eukaryote tRNA synthetases (named as in Table 1). Three points are clear. First, the time of initial acquisition of a eukaryote-specific domain is specific to the tRNA synthetase. The idiosyncratic nature of the initial acquisition, together with the observation that most domains and motifs are found in only one or a few synthetases, could suggest that each synthetase has a different expanded function (or functions)36–38.

Figure 2. Temporal elaboration of new domains for all aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases and the increasing complexity of organisms.

The appearance of new domains that have been joined to eukaryote aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases is shown for specific clades, as increasingly complex organisms are presented in evolution. Each of the clades is represented by a model species for which sequence databases were complete for the tRNA synthetases. These model species are: Homo sapiens, Danio rerio, Drosophila melanogaster, Caenorhabditis elegans and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. As a result of being limited to using model species for each clade, some domains not seen in the model species may be present in other species of the same clade, as the various databases are expanded. The ensembles of all of the domain additions are clearly indicated by the increasing numbers of each new domain in tRNA synthetases and of the multi-tRNA synthetase complex (MSC)-associated proteins that first appeared in arthropodes. Note that, once a new domain is joined to a synthetase, it is irreversibly retained as the tree of life ascends.

Second, the number of synthetases that harbour additions grows progressively as the tree of life ascends, raising the possibility that the additions themselves are part of building the complexity of higher organisms. Indeed, 19 out of 20 human tRNA synthetases (AlaRS being the exception) have added one or more new domains or motifs. For example, the number of synthetases harbouring the GST domain increases from two in fungi to four in insects to five in fish and six in humans.

Third, and most striking, once a new domain has been added to a tRNA synthetase at a specific point in evolution, it is conserved from then on as an integral part of the enzyme. Thus, progressive and accretive additions of new domains or motifs to tRNA synthetases during evolution may reflect a role for these in building the progressive complexity of organisms.

New biology correlates with new functions

To elaborate further on the possibility that these domains have roles in building the progressive complexity of organisms, we considered the development and expansion of the vascular system and the associated angiogenesis signalling pathways. If specific new domains or motifs were important for developing (or for being part of) new vascular biology associated with higher organisms, then the appearance of these domains or motifs in evolution should coincide with the emergence of the new biology. In this regard, it is interesting to note that both the ELR motif and the EMAPII domain of TyrRS and the WHEP domain of TrpRS (which have roles in vascular biology (see above)) are absent in C. elegans, which has no circulatory system. By contrast, the addition of ELR and EMAPII to TyrRS first appeared with the emergence of insects, which have a primitive open circulatory system. As blood circulation further developed into the advanced closed circulatory system of vertebrates, more regulators for angiogenesis were needed. Extra domains (or genes) added during this transition could potentially serve such a function. Interestingly, a WHEP domain was added to TrpRS at this step. In addition, a unique sequence motif UNE-S emerged in the C-terminus of SerRS of all vertebrates, from fish to humans.

Independently, three forward-genetics mutational studies in zebrafish suggested a role for SerRS in vasculature development, which is not related to the enzymatic function of the synthetase39–41. Two studies suggested a role for zebrafish SerRS in regulating VEGF-directed angiogenesis40. Specifically, they found that two of three SerRS mutations that caused defective vasculature resulted in premature stop codons that deleted the UNE-S domain40, 41. Thus, we raise the possibility that the function of UNE-S is related to the development of a closed vascular system. Similarly, the biological function of the other UNEs is of great research interest. It will be important to examine the correlation of domain additions with the emergence of other biological functions.

Markers are unique to synthetases

The biological complexity of an organism is facilitated by alternative splicing of pre-mRNAs42, post-translational modifications, paralogous gene duplications43 and the adaptation of protein multifunctionality44, 45. Among these possibilities, multifunctionality of a single protein is considered a more efficient way to coordinate the organization and maintenance of a global system46, especially for solving the discrepancy of species complexity with the limited number of host genes. Over the years, numerous proteins have been found to have many distinct functions that are achieved by domain combinations or by the modification of unused surface areas47–50. However, these multifunctional proteins belong to different protein families and their many distinct functions are specific to them. They thus lack the coherence at the family level that is seen with tRNA synthetases.

Among multifunctional proteins, ribosomal proteins are an interesting protein family 51. Many ribosomal proteins have multiple functions in bacteria, archaea and eukaryotes52, 53, and several of these functions are related to ribosomal biogenesis, such as surveillance of ribosome biosynthesis (for example, by binding of ribosomal proteins to their own mRNAs or rRNAs). In addition, numerous ribosomal proteins have non-ribosomal functions: many bind and activate p53-related E3 ligase MDM2, S3 in D. melanogaster and in mammalian cells nicks DNA at abasic sites51, and L13a participates (together with EPRS) in the GAIT complex-mediated regulation of translation of mRNAs that are associated with inflammatory pathways 54, 55.

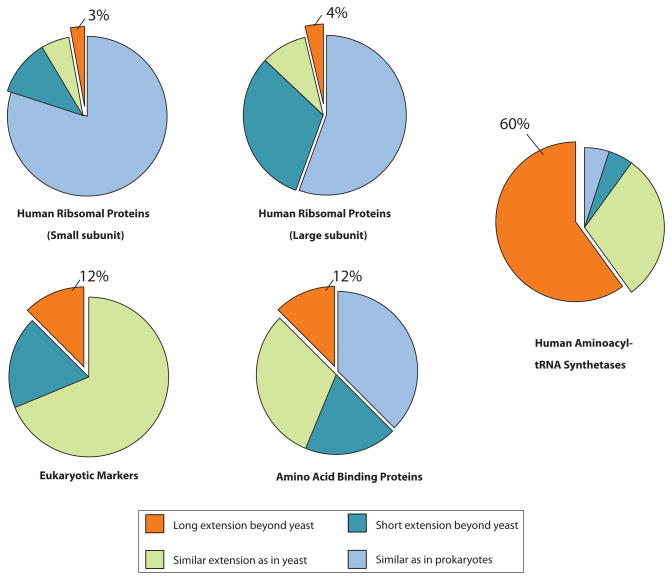

We were interested to see whether the expanded functions of the ribosomal proteins are also associated with new domain additions. For this purpose, a similar analysis to that described above was done with the ~ 80 cytoplasmic ribosomal proteins. In sharp contrast to the tRNA synthetases, more than half of the ribosomal proteins in eukaryotes are almost identical in length to their archaeal homologues (Figure 3). Most of the rest have fewer than 25 amino acids as extensions at the N or C terminus, and just seven have extensions of longer than 80 amino acids. But most striking, no stepwise, progressive additions occurred during the long evolution of eukaryotes: most of the longer extensions of human ribosomal proteins are also seen in yeast. However, with tRNA synthetases, progressive domain additions clearly correlate with the increasing complexity of organisms (Figure 2) and impart functions that are unrelated to aminoacylation.

Figure 3. Sequence extensions of human ribosomal proteins, eukaryote markers, amino acid-binding proteins, and aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases.

Sequences of each of 79 human ribosomal proteins were analyzed for appended sequences (domains or short peptide motifs) in a way similar to what was done for tRNA synthetases. The sequences were organized into four groups: similar to bacterial and archaeal orthologues (0–25 amino acids); short eukaryote-specific extensions (25–80 amino acids); lower eukaryote-specific extensions (found, for example, in yeast) that are longer than 80 amino acids, but are not further extended in species higher than yeast); and higher eukaryote-specific extensions that were added only in species higher than yeast and that are longer than 80 amino acids. Percentages for each of the four groups are shown for the human proteins. A similar analysis was done on two more groups. One was a group of 16 of 17 recently identified protein markers that can be used to assemble the eukaryotic tree of life (one protein was left out because its sequence is incomplete). Most members of this group have no bacterial or archaeal orthologue. The other was a group annotated as amino acid-binding proteins (Gene Ontology Database term 0016597). After removing duplicated genes, incomplete sequences and tRNA synthetases, sixteen proteins remained and were analysed.

Concerned about the unusual conservation of scaffolding ribosomal proteins, we also looked at a new set of eukaryotic molecular markers56. These are a group of functionally different proteins, the sequences of which can be used to construct a phylogenetic tree of eukaryote evolution. These markers include the transport protein Sec61 (a-subunit), ubiquitin-activating enzyme 1 (UBA1), spliceosome subunit U5snRNP and RNA polymerase II initiation factor TFIIH. The length of these proteins varies from 300 to ~ 2,000 amino acids. Again, tRNA synthetases showed a much higher portion (60%) of domain additions in higher eukaryotes than did these eukaryotic markers (12%) (Figure 3). A second analysis was carried out on human amino acid-binding proteins (as labeled in the Gene Ontology Database) that are shared across different species, yielding similar results.

Perspective

Our analysis indicates that aminoacyl tRNA synthetases are unique in their acquiring new activities through the addition of new domains that correlate with the progressive complexity of eukaryotes. It is important to note that some appended domains improve the canonical function. For example, the WHEP domain of human MetRS has a tRNA-sequestering function57, and the leucine-zipper motif in ArgRS is important for the formation of the MSC, which can enhance channelling of tRNA to the protein synthesis machinery58. It is therefore possible that the added domains or motifs may have later adopted new functions beyond translation.

New domains are essential for each of the three orthogonal (beyond translation) functions of the human tRNA synthetases discussed above. We speculate that other examples will also be shown to require one or more new domains or motifs for elaboration and regulation of the orthogonal activity. Two instances, among others, are human LysRS and GlnRS, which have developed functions in the immune response and cell death. LysRS is phosphorylated through the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in stimulated mast cells38. It is then released from the cytoplasmic MSC and translocated to the nucleus, where it forms a complex with the transcription factor MITF to enable the expression of genes that regulate the immune response. GlnRS interacts with ASK1 and inhibits cell death induced by ASK1 in a glutamine-dependent manner through its catalytic domain59. Although their functions have not been defined, domains not directly associated with aminoacylation have been added to each of these synthetases (Figure 2).

tRNA synthetases are ancient and were perhaps the first proteins to develop sites for binding specific amino acids. Thus, they were in an ideal spot to develop new functions. By using a pre-existing amino acid and AMP-binding pocket, as was done for the interaction of TrpRS with the protruding side chains of VE-cadherin, nature avoided the re-invention of another amino acid side chain-binding site29. Therefore, in at least some instances, the new, expanded functions of these enzymes may have been initiated through random interactions with protruding side chains on other proteins. After an initial contact, an interaction may have been further developed and refined with sophisticated domain additions to the tRNA synthetase.

It seemed plausible that amino acid-binding proteins might also have a progressive addition of new domains. However, our analysis showed that tRNA synthetases have a much higher percentage of acquired sequence extensions than these amino acid binding proteins. This result further highlights the uniqueness of tRNA synthetases, but also shows that amino acid-binding pockets are not sufficient to explain the robust development of new domains and functions associated with tRNA synthetases.

We raise the possibility that the domain additions in tRNA synthetases were needed, at least in part, for the development of the complexity of organisms, by connecting tRNA synthetases to pathways of angiogenesis16, immune response38, inflammation33, apoptosis59 and neural development15, 60. Because the aminoacylation activities of tRNA synthetases are not dispensable, the new functions had to evolve in the tight constraints of an essential genetic environment. Therefore, disease-causing mutations associated with tRNA synthetases can only occur if aminoacylation activity is kept sufficient. It is perhaps for this reason that there are many diseases associated with tRNA synthetases,61, 62 which in some instances do not involve the aminoacylation function (such as some of the dominant mutations in the genes for tyrosyl- or glycyl tRNA synthetases that cause the peripheral neuropathy Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease63–65). It will be important to investigate (in appropriate model organisms) the effects of point mutations and deletions in newly added domains on organismal development and homeostasis. It is these kinds of experiments that can test more rigorously whether these accretive domain additions were essential for building the increasing complexity of the tree of life. However, even without these data being available at this time, the existing work suggests that the new domain additions can act as starting points for discovering more functions of eukaryotic tRNA synthetases beyond translation and for also understanding some of the many disease associations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants GM 15539, GM 23562 and U54RR025204 from the National Institutes of Health, by grant CA92577 from the National Cancer Institute and by a fellowship from the National Foundation for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

Competing interest statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Carter CW., Jr Cognition, mechanism, and evolutionary relationships in aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:715–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.003435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woese CR, Olsen GJ, Ibba M, Söll D. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, the genetic code, and the evolutionary process. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:202–36. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.1.202-236.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodin SN, Ohno S. Two types of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases could be originally encoded by complementary strands of the same nucleic acid. Orig Life Evol Biosph. 1995;25:565–89. doi: 10.1007/BF01582025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pham Y, et al. A minimal TrpRS catalytic domain supports sense/antisense ancestry of class I and II aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Mol Cell. 2007;25:851–62. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ribas de Pouplana L, Schimmel P. Two classes of tRNA synthetases suggested by sterically compatible dockings on tRNA acceptor stem. Cell. 2001;104:191–3. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00204-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terada T, et al. Functional convergence of two lysyl-tRNA synthetases with unrelated topologies. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:257–62. doi: 10.1038/nsb777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ling J, Reynolds N, Ibba M. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthesis and translational quality control. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2009;63:61–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.091208.073210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo M, et al. The C-Ala domain brings together editing and aminoacylation functions on one tRNA. Science. 2009;325:744–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1174343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo M, Schimmel P, Yang XL. Functional expansion of human tRNA synthetases achieved by structural inventions. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:434–42. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.11.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rho SB, et al. Genetic dissection of protein-protein interactions in multi-tRNA synthetase complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4488–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kao J, et al. Characterization of a novel tumor-derived cytokine. Endothelial-monocyte activating polypeptide II. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:25106–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ko YG, Park H, Kim S. Novel regulatory interactions and activities of mammalian tRNA synthetases. Proteomics. 2002;2:1304–10. doi: 10.1002/1615-9861(200209)2:9<1304::AID-PROT1304>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim MJ, et al. Downregulation of FUSE-binding protein and c-myc by tRNA synthetase cofactor p38 is required for lung cell differentiation. Nat Genet. 2003;34:330–6. doi: 10.1038/ng1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park BJ, et al. The haploinsufficient tumor suppressor p18 upregulates p53 via interactions with ATM/ATR. Cell. 2005;120:209–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu X, et al. MSC p43 required for axonal development in motor neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:15944–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901872106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wakasugi K, Schimmel P. Two distinct cytokines released from a human aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase. Science. 1999;284:147–51. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wakasugi K, Schimmel P. Highly differentiated motifs responsible for two cytokine activities of a split human tRNA synthetase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23155–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kapoor M, Otero FJ, Slike BM, Ewalt KL, Yang XL. Mutational separation of aminoacylation and cytokine activities of human tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase. Chem Biol. 2009;16:531–9. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wakasugi K, et al. Induction of angiogenesis by a fragment of human tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:20124–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C200126200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strieter RM, et al. CXC chemokines: angiogenesis, immunoangiostasis, and metastases in lung cancer. Ann N Y Acad Sc. 2004;1028:351–60. doi: 10.1196/annals.1322.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tandle AT, et al. Endothelial monocyte activating polypeptide-II modulates endothelial cell responses by degrading hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha through interaction with PSMA7, a component of the proteasome. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:1850–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang XL, Skene RJ, McRee DE, Schimmel P. Crystal structure of a human aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase cytokine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15369–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242611799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang XL, et al. Gain-of-function mutational activation of human tRNA synthetase procytokine. Chem Biol. 2007;14:1323–33. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleckner J, Rasmussen HH, Justesen J. Human interferon gamma potently induces the synthesis of a 55-kDa protein (gamma 2) highly homologous to rabbit peptide chain release factor and bovine tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:11520–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wakasugi K, et al. A human aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase as a regulator of angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:173–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012602099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kise Y, et al. A short peptide insertion crucial for angiostatic activity of human tryptophanyl-tRNA synthetase. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:149–56. doi: 10.1038/nsmb722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dorrell MI, Aguilar E, Scheppke L, Barnett FH, Friedlander M. Combination angiostatic therapy completely inhibits ocular and tumor angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:967–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607542104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tzima E, et al. VE-cadherin links tRNA synthetase cytokine to anti-angiogenic function. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2405–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400431200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou Q, et al. Orthogonal use of a human tRNA synthetase active site to achieve multifunctionality. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:57–61. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang XL, et al. Crystal structures that suggest late development of genetic code components for differentiating aromatic side chains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15376–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2136794100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cerini C, Semeriva M, Gratecos D. Evolution of the aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase family and the organization of the Drosophila glutamyl-prolyl-tRNA synthetase gene. Intron/exon structure of the gene, control of expression of the two mRNAs, selective advantage of the multienzyme complex. Eur J Biochem. 1997;244:176–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cerini C, et al. A component of the multisynthetase complex is a multifunctional aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase. EMBO J. 1991;10:4267–77. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb05005.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mukhopadhyay R, Jia J, Arif A, Ray PS, Fox PL. The GAIT system: a gatekeeper of inflammatory gene expression. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34:324–31. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jia J, Arif A, Ray PS, Fox PL. WHEP domains direct noncanonical function of glutamyl-Prolyl tRNA synthetase in translational control of gene expression. Mol Cell. 2008;29:679–90. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ray PS, et al. A stress-responsive RNA switch regulates VEGFA expression. Nature. 2009;457:915–9. doi: 10.1038/nature07598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kleiman L, Cen S. The tRNALys packaging complex in HIV-1. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:1776–86. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2004.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Park SG, et al. Human lysyl-tRNA synthetase is secreted to trigger proinflammatory response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:6356–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500226102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yannay-Cohen N, et al. LysRS serves as a key signaling molecule in the immune response by regulating gene expression. Mol Cell. 2009;34:603–11. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amsterdam A, et al. Identification of 315 genes essential for early zebrafish development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12792–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403929101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fukui H, Hanaoka R, Kawahara A. Noncanonical activity of seryl-tRNA synthetase is involved in vascular development. Circ Res. 2009;104:1253–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.191189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Herzog W, Muller K, Huisken J, Stainier DY. Genetic evidence for a noncanonical function of seryl-tRNA synthetase in vascular development. Circ Res. 2009;104:1260–6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.191718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nilsen TW, Graveley BR. Expansion of the eukaryotic proteome by alternative splicing. Nature. 2010;463:457–63. doi: 10.1038/nature08909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koonin EV. Orthologs, paralogs, and evolutionary genomics. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:309–38. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.114725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu S, et al. Profiling the human protein-DNA interactome reveals ERK2 as a transcriptional repressor of interferon signaling. Cell. 2009;139:610–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Radisky DC, Stallings-Mann M, Hirai Y, Bissell MJ. Single proteins might have dual but related functions in intracellular and extracellular microenvironments. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:228–34. doi: 10.1038/nrm2633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piatigorsky J. Lens crystallins. Innovation associated with changes in gene regulation. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:4277–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jeffery CJ. Moonlighting proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:8–11. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01335-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jeffery CJ. Moonlighting proteins: old proteins learning new tricks. Trends Genet. 2003;19:415–7. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jeffery CJ. Moonlighting proteins--an update. Mol Biosyst. 2009;5:345–50. doi: 10.1039/b900658n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bashton M, Chothia C. The generation of new protein functions by the combination of domains. Structure. 2007;15:85–99. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Warner JR, McIntosh KB. How common are extraribosomal functions of ribosomal proteins? Mol Cell. 2009;34:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blumenthal T, Carmichael GG. RNA replication: function and structure of Qbeta-replicase. Annu Rev Biochem. 1979;48:525–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.48.070179.002521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wool IG. Extraribosomal functions of ribosomal proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:164–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sampath P, et al. Noncanonical function of glutamyl-prolyl-tRNA synthetase: gene-specific silencing of translation. Cell. 2004;119:195–208. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mukhopadhyay R, et al. DAPK-ZIPK-L13a axis constitutes a negative-feedback module regulating inflammatory gene expression. Mol Cell. 2008;32:371–82. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tekle YI, Grant JR, Kovner AM, Townsend JP, Katz LA. Identification of new molecular markers for assembling the eukaryotic tree of life. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2010;55:1177–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kaminska M, Shalak V, Mirande M. The appended C-domain of human methionyl-tRNA synthetase has a tRNA-sequestering function. Biochemistry. 2001;40:14309–16. doi: 10.1021/bi015670b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kyriacou SV, Deutscher MP. An important role for the multienzyme aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase complex in mammalian translation and cell growth. Mol Cell. 2008;29:419–27. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ko YG, et al. Glutamine-dependent antiapoptotic interaction of human glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase with apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:6030–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006189200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Antonellis A, et al. Glycyl tRNA synthetase mutations in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2D and distal spinal muscular atrophy type V. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1293–9. doi: 10.1086/375039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Park SG, Schimmel P, Kim S. Aminoacyl tRNA synthetases and their connections to disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:11043–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802862105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Antonellis A, Green ED. The role of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases in genetic diseases. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2008;9:87–107. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Seburn KL, Nangle LA, Cox GA, Schimmel P, Burgess RW. An active dominant mutation of glycyl-tRNA synthetase causes neuropathy in a Charcot-Marie-Tooth 2D mouse model. Neuron. 2006;51:715–26. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nangle LA, Zhang W, Xie W, Yang XL, Schimmel P. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease-associated mutant tRNA synthetases linked to altered dimer interface and neurite distribution defect. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:11239–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705055104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Storkebaum E, et al. Dominant mutations in the tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase gene recapitulate in Drosophila features of human Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:11782–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905339106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]