Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The Internet is becoming an increasingly common source of health information for patients.

OBJECTIVE:

To examine the quality of gastrointestinal disease- and symptom-related Internet sites that might be searched by patients.

METHODS:

A total of 120 websites were evaluated from July to November 2009 using the DISCERN instrument to determine the quality of content of health and treatment information.

RESULTS:

There was substantial variability in the quality of Internet resources regarding gastrointestinal diseases and their symptoms. Information-based and institutional websites were rated highest. Resources related to celiac disease, colon cancer and abdominal pain scored the highest.

CONCLUSIONS:

Overall, the quality of web-based resources was variable. Because patient education is important in the management of gastroenterological diseases, the increasing use of the Internet poses new opportunities and challenges for physicians.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal disease, Internet, Patient education, Website

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

Internet devient une source d’information sur la santé de plus en plus courante pour les patients.

OBJECTIF :

Examiner la qualité des sites Internet que les patients sont susceptibles de consulter sur les maladies gastro-intestinales et les symptômes s’y rapportant.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Au total, les chercheurs ont évalué 120 sites Web au moyen de l’instrument DISCERN entre juillet et novembre 2009, afin de déterminer la qualité du contenu de l’information sur la santé et les traitements.

RÉSULTATS :

On constatait une variabilité substantielle dans la qualité des ressources Internet sur les maladies gastro-intestinales et leurs symptômes. Les sites Web axés sur l’information et provenant d’établissements, de même que les ressources portant sur la maladie cœliaque, le cancer du côlon et les douleurs abdominales, obtenaient les notes les plus élevées.

CONCLUSIONS :

Dans l’ensemble, la qualité des ressources Internet était variable. Puisque l’éducation des patients est un volet important de la prise en charge des maladies gastroentérologiques, l’utilisation croissante d’Internet entraîne de nouvelles possibilités et de nouveaux défis pour les médecins.

Use of the Internet among Canadians has increased substantially over the past decade, with recent figures estimating the number of users to be approximately 25 million (1). Among these users are patients seeking disease-related knowledge through the World Wide Web (2). The type of information sought by such patients is often related to the causes and treatment of illnesses (3).

Although use of the Internet to obtain health information varies with disease type, recent studies (4–8) on patients attending gastroenterology clinics report usage rates of between 42% and 92.6%. This trend is likely to continue, with more than 60% of individuals reporting probable future use in one study of patients with irritable bowel syndrome (9). Only a small proportion of patients have been found to seek this information on the Internet on the advice of their physician (10). Thus, patients are often seeking Internet resources without knowledge of the accuracy or quality of the information presented on these websites.

Using the validated DISCERN instrument (11–14), the purpose of the present study was to determine the quality of web resources potentially sought by patients pertaining to gastroenterological diseases and their common symptoms.

QUICK REFERENCE GUIDE TO THE DISCERN CRITERIA

A good quality publication about treatment choices will have the following attributes:

Explicit aims

Achieve its aims

Be relevant to consumers

Make sources of information explicit

Make the date of information explicit

Be balanced and unbiased

List additional sources of information

Refer to areas of uncertainty

Describe how treatment works

Describe the benefits of treatment

Describe the risks of treatment

Describe what would happen without treatment

Describe the effects of treatment choices on overall quality of life

Make it clear that there may be more than one possible treatment choice

Provide support for shared decision making

This guide should only be used once one is acquainted with the full DISCERN instrument (14).

METHODS

Internet search

Websites were identified by entering search terms into the Internet search engine ‘Google’ (Google Inc, USA) from July to November 2009. Search terms related to eight common gastroenterological diseases included the following: “hepatitis”, “liver cirrhosis”, “Crohn’s disease”, “ulcerative colitis”, “celiac disease”, “irritable bowel syndrome”, “peptic ulcer disease” and “colon cancer”. In addition, search terms related to four common gastroenterological symptoms including “abdominal pain”, “diarrhea”, “constipation” and “heartburn” were also used.

Identification of websites for evaluation

The first 10 relevant results for each of the search terms were identified and evaluated. Inclusion criteria for eligibility were that the website provided information pertaining to the disease or symptom search term, and were written in English. Websites were excluded from the study if they were portal sites, news sites, book results, video results, medical dictionaries, dead links, duplicate sites or contained information irrelevant to the search term. In an effort to include websites that patients might access during an Internet search, the top 10 were selected based on whether they included information related to the disease or symptom, and not based on the quality of the information.

Website evaluation

The identified websites were then classified according to type (Table 1). The quality of content was assessed using the validated DISCERN tool (11–14). This instrument is available online (www.discern.org.uk) for evaluating the quality of health information. It consists of 15 questions pertaining to content, and rated on a scale of 1 to 5 (5 being the highest score). The 16th question relates to the overall quality of the publication as determined by the user.

TABLE 1.

Categorization of websites

| Website category | Example |

|---|---|

| Information | http://en.wikipedia.org |

| Institution | www.mayoclinic.com |

| Organization | www.coloncancerfoundation.org |

| Pharmaceutical | www.remicade.com |

| Alternative medicine | www.aarogya.com |

| Blog/other | www.mamashealth.com/default.asp |

The DISCERN tool was used by each of the authors to independently assess the websites identified. Websites found using disease-based search terms were evaluated with the full DISCERN tool, while the sites found using symptom-based search terms were evaluated with questions 1 to 8 of DISCERN. Questions 9 to 15 of DISCERN deal primarily with disease treatment rather than disease states, and do not necessarily apply to symptoms only. Thus, websites found using symptom-based search terms were evaluated with this abridged DISCERN tool.

RESULTS

The first 10 websites reported by the search engine ‘Google’ for each of the search terms were studied, yielding a total of 120 websites. The websites were categorized as information based (38.3%, n=46), institution (35.8%, n=43), organization (20.8%, n=25), pharmaceutical (2.5%, n=3), alternative medicine (1.7%, n=2) and blog (0.8%, n=1).

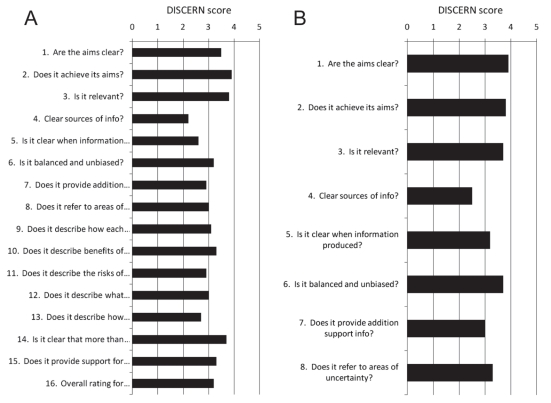

The mean DISCERN scores for all websites are shown in Figures 1A and 1B. Tables 2 and 3 summarize the mean DISCERN scores according to website category, and according to specific disease- or symptom-based search term. The highest-rated websites according to search term are shown in Table 4. Table 5 lists the highest-rated websites overall.

Figure 1).

Mean DISCERN scores for all websites. A Websites found using disease-based search terms were evaluated with the full DISCERN tool. B Websites found using symptom-based search terms were evaluated with questions 1 to 8 of the DISCERN tool. info Information

TABLE 2.

DISCERN scores for websites according to category (n=120)

| Type of website | Websites identified, n (%) | DISCERN score, mean (range) |

|---|---|---|

| Information | 46 (38.3) | 3.5 (2.1–4.8) |

| Institution | 43 (35.8) | 3.1 (2.1–4.6) |

| Organization | 25 (20.8) | 3.2 (2.6–4.4) |

| Pharmaceutical | 3 (2.5) | 3.0 (1.4–3.8) |

| Alternative medicine | 2 (1.7) | 1.2 (1.1–1.3) |

| Blog/other | 1 (0.8) | 1.3 (–) |

TABLE 3.

DISCERN scores for websites according to search term

| Search term | DISCERN score, mean (range) |

|---|---|

|

Diseases | |

| Hepatitis | 2.7 (1.8–4.2) |

| Liver cirrhosis | 2.7 (1.3–4.7) |

| Crohn’s disease | 2.9 (1.4–4.3) |

| Ulcerative colitis | 3.3 (2.1–4.6) |

| Celiac disease | 3.7 (2.2–4.7) |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 3.2 (2.3–4.5) |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 3.1 (1.7–4.3) |

| Colon cancer | 3.6 (2.2–4.8) |

|

Symptoms* | |

| Abdominal pain | 3.7 (3.1–4.3) |

| Diarrhea | 3.3 (2.4–4.8) |

| Constipation | 3.3 (2.6–4.5) |

| Heartburn | 3.4 (2.6–4.4) |

Websites found using symptom-based search terms were evaluated using the abridged DISCERN tool

TABLE 4.

Top-rated websites and corresponding DISCERN scores according to search term

Websites found using symptom-based search terms were evaluated with questions 1 to 8 of the DISCERN tool

TABLE 5.

Top-rated websites according to DISCERN score

| Rank | Website | Category | DISCERN score, mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | http://emedicine.medscape.com | Information | 4.4 |

| 2 | http://en.wikipedia.org | Information | 4.3 |

| 3 | http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov | Institution | 3.6 |

DISCUSSION

The present study examined the quality of websites possibly used by patients using the Google search engine seeking information pertaining to gastroenterological diseases and symptoms. The majority of the websites found were information, institution or organization based. Overall, Internet resources did not score highly when evaluated with the DISCERN tool. Most websites did well in providing clear objectives and achieving them, but fared poorly in areas such as clearly identifying information sources and describing treatments. Informational websites and those that were organization-based received the highest mean DISCERN scores. Although alternative medicine and blog sites were rated poorly, there was an insufficient number of these websites to confidently draw firm conclusions.

Websites pertaining to abdominal pain, celiac disease and colon cancer were rated highly, while hepatitis and liver cirrhosis sites were rated poorly (Table 3). The web resource www.emedicine.medscape.com, ranked highest among websites, with a mean overall DISCERN score of 4.4 (Table 5).

Results of other studies examining the quality of gastroenterological websites have been published. One study (15) showed that inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) websites were usually of fair to poor quality and were difficult to understand for the average reader. Systematic reviews (16,17) have found significant variability in the quality of IBD sites, with one study (17) identifying websites lacking information pertaining to funding sources and the date of the most recent update.

Similar to the results presented here, hepatological websites were found to score poorly with regard to accuracy, reliability and depth (18). Although we found that celiac disease websites scored well, another study (19) found that 66% of such resources scored less than 50% accuracy in the medical information provided. Internet sources on colorectal cancer were often of poor quality, with the source of information clear in less than 50% of the websites (20).

The quality of medical information presented was correlated with the type of website. IBD resources classified as alternative medicine sites were of significantly lower quality than institutional or pharmaceutical sites (15), which is similar to the findings presented in our study. Hepatological websites that were commercially sponsored scored substantially lower than other types of websites, with more than 60% not including financial disclosure statements (18).

Another study of IBD patients (6) found that patients were most likely to seek institution- or organization-based websites. Of these patients, 57% rated Internet information as ‘trustworthy’ or ‘very trustworthy’. Another study (4) reported that up to 66% of patients believed that the Internet was a good source of medical information. These studies emphasized the need to evaluate such web-based resources for quality of content.

Our study has inherent limitations. Internet resources are frequently modified, making our conclusions valid for only a certain period of time. This is especially true of openly edited Internet sites such as http//en.wikipedia.org. Furthermore, websites found by patients would vary with the search engine used and geographical location of the search. Although the full DISCERN instrument used by two physician evaluators to rate the websites has been validated, the abridged DISCERN tool used to evaluate symptom-based web resources has not. There was only minor variability among DISCERN scores assigned by each evaluator, with the results showing general agreement. However, inter-rater agreement was not statistically analyzed in the current study.

Results of the present study showed that most web resources that might be searched by patients seeking gastroenterological health information are of mediocre quality. A few websites have been identified as being of higher quality and can be recommended by physicians to patients seeking web-based information. Patient education remains an important component in the management of gastroenterological diseases, and the increasing use of the Internet among Canadians poses new opportunities and challenges.

REFERENCES

- 1.International Telecommunications Union Internet indicators: Subscribers, users, and broadband subscribers. < http://www.itu.int/ITU-D/icteye/Reporting/ShowReportFrame.aspx?ReportName=/WTI/InformationTechnologyPublic&RP_intYear=2008&RP_intLanguageID=1> (Accessed on October 7, 2009).

- 2.Richard B, Colman AW, Hollingsworth RA. The current and future role of the Internet in patient education. Int J Med Inform. 1998;50:279–85. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(98)00083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roshandel D, Rezailashkajani M, Ansari S, et al. Internet use by a referral gastroenterology clinic population and their medical information preferences. Int J Med Inform. 2005;74:447–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alarcón O, Baudet JS, Sánchez Del Río A, et al. Internet use to obtain health information among patients attending a digestive diseases office. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;29:286–90. doi: 10.1157/13087467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angelucci E, Orlando A, Ardizzone S. Internet use among inflammatory bowel disease patients: An Italian multicenter survey. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:1036–41. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328321b112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cima RR, Anderson KJ, Larson DW, et al. Internet use by patients in an inflammatory bowel disease specialty clinic. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:1266–70. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panés J, de Lacy AM, Sans M, et al. Frequent Internet use among Catalan patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;25:306–9. doi: 10.1016/s0210-5705(02)79024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halpert A, Dalton CB, Palsson O, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome patients’ ideal expectations and recent experiences with healthcare providers: A national survey. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:375–83. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0855-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halpert A, Dalton CB, Palsson O, et al. Patient educational media preferences for information about irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:3184–90. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0280-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Connor JB, Johanson JF. Use of the Web for medical information by a gastroenterology clinic population. JAMA. 2000;284:1962–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.15.1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charnock D, Shepperd S, Needham G, et al. DISCERN: An instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53:105–11. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.2.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Griffiths KM, Christensen H. Website quality indicators for consumers. J Med Internet Res. 2005;7:e55. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7.5.e55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rees CE, Ford JE, Sheard CE. Evaluating the reliability of DISCERN: A tool for assessing the quality of written patient information on treatment choices. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;47:273–5. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00225-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quick reference guide to the DISCERN criteria. < http://www.discern.org.uk/> (Accessed on December 22, 2010).

- 15.van der Marel S, Duijvestein M, Hardwick JC, et al. Quality of web-based information on inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1891–6. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernard A, Langille M, Hughes S, et al. A systematic review of patient inflammatory bowel disease information resources on the world wide web. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2070–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langille M, Bernard A, Rodgers C, et al. Systematic review of the quality of patient information on the internet regarding inflammatory bowel disease treatments. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:322–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fraquelli M, Conte D, Cammà C, et al. Quality-related variables at hepatological websites. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36:533–8. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.England CY, Nicholls AM. Advice available on the Internet for people with coeliac disease: An evaluation of the quality of websites. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2004;17:547–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2004.00561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al-Bahrani A, Plusa S. The quality of patient-orientated internet information on colorectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2004;6:323–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2004.00604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]