Abstract

Objective To determine whether new programmes developed to widen access to medicine in the United Kingdom have produced more diverse student populations.

Design Population based cross sectional analysis.

Setting 31 UK universities that offer medical degrees.

Participants 34 407 UK medical students admitted to university in 2002-6.

Main outcome measures Age, sex, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity of students admitted to traditional courses and newer courses (graduate entry courses (GEC) and foundation) designed to widen access and increase diversity.

Results The demographics of students admitted to foundation courses were markedly different from traditional, graduate entry, and pre-medical courses. They were less likely to be white and to define their background as higher managerial and professional. Students on the graduate entry programme were older than students on traditional courses (25.5 v 19.2 years) and more likely to be white (odds ratio 3.74, 95% confidence interval 3.27 to 4.28; P<0.001) than those on traditional courses, but there was no difference in the ratio of men. Students on traditional courses at newer schools were significantly older by an average of 2.53 (2.41 to 2.65; P<0.001) years, more likely to be white (1.55, 1.41 to 1.71; P<0.001), and significantly less likely to have higher managerial and professional backgrounds than those at established schools (0.67, 0.61 to 0.73; P<0.001). There were marked differences in demographics across individual established schools offering both graduate entry and traditional courses.

Conclusions The graduate entry programmes do not seem to have led to significant changes to the socioeconomic profile of the UK medical student population. Foundation programmes have increased the proportion of students from under-represented groups but numbers entering these courses are small.

Introduction

Recent years have seen major initiatives designed to increase the demographic diversity among medical students. The rationale for doing so centres on providing more culturally sensitive healthcare to increasingly heterogeneous populations and achieving social justice among groups historically under-represented in medicine.1 2

The argument that increasing diversity would improve healthcare centred originally on an assumption that “like would treat like,” an assumption that has been questioned.3 More recently, it has been suggested that students who train in demographically diverse medical schools have educational and professional advantages—that is, they gain a greater understanding of the experiences of others and their sociocultural backgrounds, which increases their ability to provide healthcare to people with backgrounds different from their own.4 5

The imperative of achieving social justice was first proposed in the United States with regard to race equalities and in the context of historic discrimination and restricted civil rights. In the United Kingdom attention has focused less on race and more on the lack of educational opportunities for people from materially disadvantaged families and communities. This focus has become particularly apparent under the recent Labour governments, for whom social mobility, gained via education, is a key political imperative.6

In the UK, assessment of diversity is complicated by the relationship between ethnicity and social class. At a superficial level, it seems that most students are white and from affluent backgrounds. This superficiality, however, betrays a more complex picture—for example, representation of students of south Indian origin is substantially higher than expected, while white men are under-represented.7 Regardless of ethnicity, there is a consistent lack of students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. In response to this, recent Labour governments exhorted universities to widen access to medicine.6 8 9

Traditionally, and until the mid-1990s, medical training in the UK encompassed almost universal provision of a five year undergraduate programme usually accessed by school leavers (that is, students who complete their schooling aged 18-19 and enter university within 12 months having attained the required educational standard, usually measured by performance in advanced level or international baccalaureate examinations).10 In addition, a small number of universities offer a 1+5 year programme for high achieving school leavers who wanted to study medicine but who have studied arts subjects at secondary school and hence require an initial period of 12 months’ study to educate them in basic sciences (pre-medical programmes).

In response to calls to increase and to diversify the student population, two new types of programmes were developed. The largest of these is the graduate entry course (GEC) programme, which was designed to offer students who did not enter medicine as a school leaver an opportunity to do so once they had completed a non-medical first degree. The rationale for introducing such programmes is twofold. Firstly, it is a means of shortening the training period and hence redresses dwindling workforce numbers more rapidly. Secondly, it targets more mature students for whom medicine is a considered choice and who, it has been assumed, will be more motivated and have better learning skills and superior academic performance than school leaver entrants.11 12 This focus on mature students has been heralded as a means of increasing the diversity of intakes of medical students by admitting university graduates who might have been unable to enter medical school straight from school because of relatively poor exam results.3 13 On a much smaller scale, three UK universities developed foundation programmes, access to which is restricted to students with specific demographics characteristic of population groups traditionally under-represented in medicine. In addition, a handful of institutions explicitly reserve some places on traditional programmes for students from challenging backgrounds,14 15 but these schemes are not widespread.

The proportion of students from the lowest socioeconomic groups entering medicine in the UK has remained more or less constant over the past decade.16 Within the past 18 months, however, the first detailed evaluations of the two new types of programme have emerged. An analysis of a single case study graduate entry course programmes suggested the course had brought greater diversity in terms of more men and more students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds,3 while a description of the experiences and performance of the first cohort of qualifying students admitted to a foundation programme was markedly positive.17 Yet these “good news” stories have not been accepted without challenge: concerns expressed include the cost of foundation programmes,18 the morality of restricting access to specific demographic groups,19 and whether graduate entry courses truly do access students who “missed” out on medicine at school leaving age because of a lack of educational opportunity or merely (re)capture those from traditionally represented demographic groups who missed out on medicine first time round.13

We analysed population based data for all students resident in the UK who were admitted to medical schools during the five year period 2002-6. Specifically, we examined whether the implementation of new programmes—graduate entry courses and foundation—has achieved further demographic diversity within the student population.

Methods

We used a download of anonymised data from the Universities and Colleges Admissions Service (UCAS), comprising demographic information for each individual applicant to a UK medical school for 2002-6. UCAS is the national centralised service through which applications to university programmes are processed, and case ascertainment and accuracy of the database is anticipated to be near 100%.20

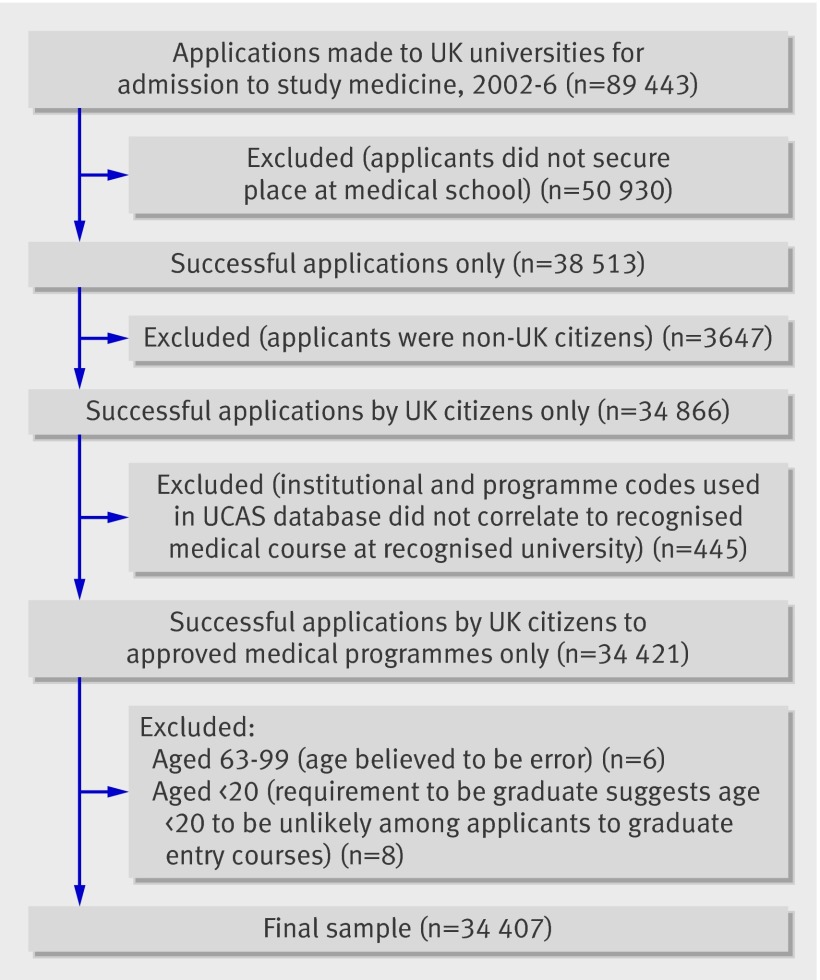

We restricted our analyses to “home” students who were accepted on to a programme leading to a recognised medical degree (figure). Home students are defined by UCAS as applicants whose permanent residence has a UK postcode. We recognise that this does not concur completely with the definitions used by universities, whereby for a student to be eligible for home fee status, she or he must have been ordinarily resident in the UK or elsewhere in the European Union, European Economic Area (European Union plus Norway, Iceland, and Liechtenstein), or Switzerland for the three years. Thus, for example, non-home applicants who were temporarily resident in the UK at the time of application (for example, at a UK boarding school) might be included in our study population. We believe that, if present, such students will comprise only a tiny fraction of our sample.

Derivation of sample of UK medical students, 2002-6

For each case we abstracted information on age, sex, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. UCAS uses a simplified version of the National Statistics Socio-economic Classification (NS-SEC)21 to assign socioeconomic status to applicants. Status is based on an applicant’s parental occupation (highest earner) (or the occupation of the person contributing the highest income to the household if the applicant is aged 21 or over). Seven categories of occupation are available and are broadly hierarchical in their structure (table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of students admitted to medical degree programmes, 2002-6

| Traditional courses | Graduate entry courses (n=2948) | Pre-medical courses (n=480) | Foundation courses (n=325) | All courses (n=34 407) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All universities (n=30 654) | Established universities (n=28 136) | New universities (n=2518) | |||||

| Sex: | |||||||

| Male | 12 311 (40) | 11 286 (40) | 1025 (41) | 1238 (42) | 156 (33) | 123 (38) | 13 828 (40) |

| Female | 18 343 (60) | 16 850 (60) | 1493 (59) | 1710 (58) | 324 (68) | 202 (62) | 20 579 (60) |

| Age (years): | |||||||

| Mean | 19.2 | 19.0 | 21.5 | 25.5 | 22.2 | 20.9 | 19.8 |

| Median (IQR) | 18 (18-19) | 18 (18-19) | 19 (19-23) | 24 (22-27) | 20 (18-24) | 19 (18-20) | 18 (18-19) |

| Range | 17-51 | 17-51 | 17-51 | 20-51 | 17-46 | 17-51 | 17-51 |

| Ethnicity*: | |||||||

| White | 21 415 (70) | 19 459 (69) | 1956 (78) | 2462 (84) | 405 (84) | 73 (23) | 24 355 (71) |

| Mixed | 971 (3) | 890 (3) | 81 (3) | 82 (3) | 11 (2) | 14 (4) | 1078 (3) |

| Other | 519 (2) | 486 (2) | 33 (1) | 16 (1) | 7 (2) | 16 (5) | 558 (2) |

| Black Caribbean | 86 (0.3) | 80 (0.28) | 6 (0.24) | 14 (1) | 2 (0.4) | 8 (3) | 110 (0.3) |

| Black African | 602 (12) | 536 (2) | 66 (3) | 53 (2) | 6 (1) | 86 (27) | 747 (2) |

| Black other | 33 (0.1) | 29 (0.10) | 4 (0.16) | 1 (0) | 1 (0.2) | 3 (1) | 38 (0.1) |

| Pakistani | 1342 (4) | 1252 (4) | 90 (4) | 68 (2) | 9 (2) | 34 (11) | 1453 (4) |

| Bangladeshi | 288 (1) | 268 (1) | 20 (1) | 15 (1) | 1 (0.2) | 32 (10) | 336 (1) |

| Indian | 2917 (10) | 2778 (10) | 139 (6) | 112 (4) | 8 (2) | 18 (6) | 3055 (9) |

| Chinese | 720 (2) | 704 (3) | 16 (1) | 25 (1) | 7 (2) | 4 (1) | 756 (2) |

| Other Asian | 1265 (4) | 1199 (4) | 66 (3) | 53 (2) | 8 (2) | 29 (9) | 1355 (4) |

| Not known | 496 (2) | 455 (2) | 41 (2) | 47 (2) | 15 (3) | 8 (3) | 566 (2) |

| Parental occupation: | |||||||

| Higher managerial-professional | 12 528 (41) | 11 715 (42) | 813 (32) | 801 (27) | 141 (29) | 24 (8) | 13 495 (39) |

| Lower managerial- professional | 7615 (25) | 6934 (25) | 681 (27) | 614 (21) | 129 (27) | 73 (23) | 8433 (25) |

| Intermediate occupations | 2949 (10) | 2677 (10) | 272 (11) | 256 (9) | 57 (12) | 40 (13) | 3301 (10) |

| Lower supervisory-technical | 576 (2) | 533 (2) | 43 (2) | 15 (1) | 7 (2) | 7 (2) | 604 (2) |

| Routine occupations† | 522 (2) | 478 (2) | 44 (2) | 18 (1) | 6 (1) | 15 (5) | 562 (2) |

| Semiroutine occupations‡ | 1730 (6) | 1573 (6) | 157 (6) | 215 (7) | 25 (5) | 51 (16) | 2026 (6) |

| Small employers-own account workers | 1227 (4) | 1123 (4) | 104 (4) | 40 (1) | 20 (4) | 14 (5) | 1302 (4) |

| Not stated | 3507 (11) | 3103 (11) | 404 (16) | 989 (34) | 95 (20) | 88 (28) | 4684 (14) |

*Original UCAS dataset noted over 20 different ethnic groups based on National Census descriptors, here compressed into these 12 groups for ease of analysis.

†Examples include HGV/van driver; cleaner; bar staff.

‡Examples include postal worker, security guard, receptionist.

Among institutions offering the traditional five year undergraduate programmes (traditional courses), we identified a subset of medical schools formed within the past decade (“new” schools; n=4) that have stated a different approach to student admissions.22 In our analysis we compared these new schools with the pre-existing schools (“established”; n=25).

When comparing the characteristics of students across the four types of course we used multilevel modelling techniques to account for variability because of the universities. All analyses comparing the characteristics of students across course types were carried out with multilevel models. Differences between categorical measures (sex, background, and ethnicity) are expressed as odds ratios and between numerical characteristics (age) as differences in means.

Results

During 2002-6, 31 universities offered programmes leading to a medical degree. We include St Andrew’s as a separate university but recognise that its students presently complete clinical training elsewhere. Twelve schools offered only a traditional course; seven offered a traditional course and a graduate entry course; two offered a traditional course, a graduate entry course, and pre-medical entry; two offered a traditional course, a graduate entry course, and foundation entry; five offered a traditional course and pre-medical entry; two offered a graduate entry course only; and one offered all four types of course.

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of students on the four types of course. Overall, three fifths of students were women (n=20 579), 71% (24 355) defined their ethnicity as white, and 39% (13 495) were from higher managerial and professional (HMP) backgrounds. The demographics of the 325 (1%) students admitted to foundation courses were markedly different from those on traditional, graduate entry, and pre-medical courses: only 23% (73) of foundation students defined their ethnicity as white and only 8% (24) defined their background as higher managerial and professional (table 1).

Compared with students on the traditional course, students on the foundation course were less likely to be white (odds ratio 0.21, 95% confidence interval 0.16 to 0.28; P<0.001) or have a higher managerial and professional background (0.13, 0.09 to 0.20; P<0.001) (table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of students on graduate entry courses (GEC), pre-medical, and foundation courses compared with students on traditional courses, and of traditional students attending new and established schools, 2002-6. Figures are differences in means (for age) or odds ratios (95% confidence interval), P values

| GEC v traditional | Pre-medical v traditional | Foundation v traditional | New v established schools | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 6.9 (6.8 to 7.1), <0.001 | 3.1 (2.9 to 3.4), <0.001 | 1.6 (1.2 to 1.9), <0.001 | 2.5 (2.4 to 2.7), <0.001 |

| Sex (male v female) | 1.08 (0.98 to 1.18), 0.107 | 0.77 (0.63 to 0.94), 0.010 | 0.95 (0.76 to 1.21), 0.699 | 1.03 (0.94 to 1.11), 0.560 |

| Ethnicity (white v non-white) | 3.74 (3.27 to 4.28), <0.001 | 2.54 (1.95 to 3.31), <0.001 | 0.21 (0.16 to 0.28), <0.001 | 1.55 (1.41 to 1.71), <0.001 |

| Socioeconomic background (higher v non-higher) | 0.60 (0.54 to 0.66), <0.001 | 0.60 (0.49 to 0.73), <0.001 | 0.13 (0.09 to, 0.20), <0.001 | 0.67 (0.61 to 0.73), <0.001 |

Over 97% of students were enrolled on either traditional or graduate entry programmes. The odds ratio of male students on graduate entry programmes compared with traditional courses was not significant (1.08, 0.98 to 1.18; P=0.107) nor between students on traditional courses at established and new schools (1.03, 0.94 to 1.11; P=0.560) (table 2). Students on graduate entry courses were significantly older, by an average of 6.9 years (6.8 to 7.1; P<0.001) and more likely to be white (3.74, 3.27 to 4.28; P<0.001) than students on traditional courses. Students on traditional courses at new schools were significantly older, by an average of 2.5 years (2.4 to 2.7; P<0.001) and more likely to be white (1.55, 1.41 to 1.71; P<0.001) than students on similar courses at established schools (table 2).

Two fifths of students on traditional courses declared their parental occupation to be higher managerial and professional (n=12 528) compared with 27% (801) of students on graduate entry courses (table 1). Among students on traditional courses, those training at new schools were significantly less likely to have higher managerial and professional backgrounds than those at established schools (0.67, 0.61 to 0.73; P<0.001) (table 2).

Exploration of the demographics of individual established schools offering both graduate entry courses and traditional programmes shows marked variation between institutions (table 3): the proportion of women on traditional courses ranged from 54% to 64%; the proportion of white students from 33% to 84%, and the proportion of students with higher managerial and professional backgrounds from 32% to 56%. Similar variation between institutions was noted among graduate entry courses (41% to 69% for women; 67% to 96% for white ethnicity; and 20% to 41% for higher managerial and professional background).

Table 3.

Characteristics of students at 12 established medical schools that offer both traditional and graduate entry courses (GEC)

| University and course | No of students | No (%) of women | Mean (median) age (years) | No (%) white | No (%) from higher managerial-professional background | No (%) with missing information on parental occupation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-Traditional | 1754 | 1086 (62) | 18.5 (18) | 1104 (63) | 809 (46) | 151 (9) |

| A-GEC | 169 | 107 (63) | 23.9 (23) | 140 (83) | 61 (36) | 68 (40) |

| B-Traditional | 1116 | 710 (64) | 19.1 (18) | 937 (84) | 506 (45) | 122 (11) |

| B-GEC | 47 | 32 (68) | 26.6 (25) | 41 (87) | 18 (38) | 15 (32) |

| C-Traditional | 1223 | 665 (54) | 18.3 (18) | 793 (65) | 654 (54) | 78 (6) |

| C-GEC | 105 | 65 (62) | 25.3 (24) | 92 (88) | 33 (31) | 40 (38) |

| D-Traditional | 1420 | 892 (63) | 19.2 (18) | 610 (43) | 565 (40) | 208 (15) |

| D-GEC | 73 | 36 (49) | 26.3 (25) | 70 (96) | 19 (26) | 28 (38) |

| E-Traditional | 878 | 475 (54) | 19.4 (18) | 470 (54) | 309 (35) | 116 (13) |

| E-GEC | 247 | 167 (68) | 27.0 (25) | 196 (79) | 55 (22) | 30 (12) |

| F-Traditional | 1390 | 872 (63) | 19.1 (18) | 1074 (77) | 482 (35) | 154 (11) |

| F-GEC | 124 | 85 (69) | 23.7 (22) | 111 (90) | 34 (27) | 29 (23) |

| G-Traditional | 1492 | 913 (61) | 19.1 (18) | 1236 (83) | 587 (39) | 165 (11) |

| G-GEC | 149 | 88 (59) | 25.4 (24) | 134 (90) | 42 (28) | 52 (35) |

| H-Traditional | 1113 | 703 (63) | 18.4 (18) | 859 (77) | 512 (46) | 75 (7) |

| H-GEC | 355 | 146 (41) | 27.8 (26) | 310 (87) | 123 (35) | 93 (26) |

| I-Traditional | 739 | 418 (57) | 18.1 (18) | 566 (77) | 417 (56) | 38 (5) |

| I-GEC | 113 | 52 (46) | 25.2 (25) | 104 (92) | 46 (41) | 53 (47) |

| J-Traditional | 1214 | 680 (56) | 19.9 (19) | 397 (33) | 384 (32) | 230 (19) |

| J-GEC | 155 | 105 (68) | 25.4 (24) | 103 (67) | 43 (28) | 50 (32) |

| K-Traditional | 885 | 536 (61) | 19.5 (18) | 705 (80) | 356 (40) | 102 (12) |

| K-GEC | 123 | 80 (65) | 24.9 (23) | 102 (83) | 25 (20) | 55 (45) |

| L-Traditional | 836 | 479 (57) | 19.9 (18) | 365 (44) | 286 (34) | 139 (17) |

| L-GEC | 363 | 194 (53) | 27.4 (26) | 324 (89) | 102 (28) | 96 (26) |

Discussion

Key findings

In this national analysis of the demographic characteristics of the four types of medical programmes offered in the UK, our results show that students on graduate entry courses are, as would be expected, significantly older than the school leavers who access traditional courses and are more likely to define themselves as white. Across all medical schools we found no significant difference in the proportion of men and women between graduate entry courses and traditional courses.

Traditional courses run at newer schools seem to attract a different type of student: older and more likely to be white and from a less affluent family background than students on traditional courses at established schools (table 1). This might reflect an institutional policy to “be different,”22 and indeed there is some evidence from qualitative work with mature and with working class students that new schools might be more sympathetic to their “different” background than the established schools.23 24 Longer term analysis of the demography of these schools over the next decade will show whether they maintain their difference.

The greater proportion of white students on graduate entry courses is interesting. White male applicants have been under-represented compared with the wider population,7 and our analyses suggest that the sex imbalance among white students observed on traditional courses (66% of men and 73% of women are white) is being redressed on the graduate entry courses (82% men and 85% of women are white).

Strengths and limitations

The variables we used (age, sex, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status) are derived from standard definitions that remained the same over the study period. All are self defined by the applicant but information on ethnicity and socioeconomic status are voluntarily provided, which results in a major challenge in monitoring widening participation. Firstly, neither individual level (derived from applicants’ parental occupation) nor area based (from applicants’ postcode) measures of socioeconomic position offer a complete and unbiased picture of the student population enrolling on medical programmes.25 Secondly, the inter-relation between ethnicity and socioeconomic status in the UK is complex, and thus when we look at socioeconomic status, we are also stratifying, in part, by ethnicity. Given the previously reported direction of biases in under-reporting of socioeconomic status by students from different ethnic backgrounds in their UCAS applications,25 we would suggest the observed lower percentage from higher managerial and professional backgrounds seen on graduate entry courses (27%), where over 80% of students are white, is, when compared with traditional courses (41% with higher managerial and professional backgrounds), probably an overestimation of actual difference when missing data are considered. Indeed, the proportions of students who declare their backgrounds to be from non-managerial classes and non-professional classes is marginally lower among students on graduate entry courses than those on traditional courses (8% v 9%; table 1).

The ability to unpick the impact of efforts to widen access is further limited by available data. We could not examine the impact of some institution specific initiatives for participants entering traditional programmes (see for example, those at St George’s14 and Sheffield15), which are not separately identifiable via UCAS data. Nonetheless, the efforts of the three schools offering foundation programmes seem to have been far more successful in diversifying the future medical profession than the more widespread graduate entry initiative. Foundation programmes, however, contribute a tiny fraction to the annual national intake of medical students, and it is unsurprising therefore that little impact on the national picture has emerged, in which the proportion of students from under-represented groups remains steady.16

Explanations for the study’s findings

Given that UK medical schools are legally permitted to modify their admission policies to increase applications from under-represented groups,16 why are more universities not operating foundation programmes or offering explicit adjusted entry criteria to traditional courses? One reason might be that while public funds are available to assist universities take forward schemes to increase diversity,26 27 foundation programmes require a markedly higher per capita resource allocation than other programmes.18 But Carrasquillo and Lee-Rey, speaking from a US perspective, identify several more subtle reasons, which have parallels in the UK.28 Firstly, there might be misunderstandings by universities about the success (or otherwise) of their existing selection strategies in allowing for differential educational opportunities among applicants. In the UK, most medical schools now use cognitive testing as part of their selection processes in the belief that such tests measure inherent aptitude rather than aspects of ability that could be influenced by quality of teaching in secondary schools and educational environment.10 Reliance on such tests might be overoptimistic: an assessment of the recently introduced and widely used UK clinical aptitude test concluded that it has an inherent favourable bias to men, to students from more affluent backgrounds, and to students educated at private or selective entry secondary schools.29

Secondly, at a time of championing widening participation in university education, the Labour government introduced variable top-up tuition fees, leaving medical students with debts of around £40 000 (€47 000, $64 000) at the end of training.16 30 Evidence suggests that while all students are concerned about the costs of medical degrees, only those from lower socioeconomic groups are likely to see it as a constraint on their choice of degree.31

Thirdly, societal pressures might be acting. Public awareness of the political pressure on universities to increase diversity has been raised in recent years.32 In turn, a “backlash” has emerged with the more right wing media and society’s “middle classes,” objecting to affirmative action.33 34

Fourthly, and perhaps most powerful and problematic, there might not be genuine commitment to increase diversity by medicine and the academy. This should not surprise us: medicine is an elite profession, and, by definition, elite professions and institutions erect boundaries and control admission such that elitism remains.35 To this end it is interesting to note that the shift in the past 20 years from one of male dominance to one of female preponderance in the annual national entry cohort of medical students prompted a recent (and female) president of the Royal College of Physicians to suggest that the feminisation of medicine risked the profession’s elite status,36 comments that prompted substantial discussion.37

Conclusion and implications for policy

Evidence of the advantages of increasing diversity is emerging, but the implementation of “new” admission routes to the profession does not seem to be bringing significant change. Those familiar with the history of medical education in the US are unlikely to be surprised by these observations: medicine has always been a graduate programme in the US and yet the involvement of under-represented groups remains relatively low. In both the US and UK, the most successful programmes to increase student diversification seem to be those based on explicit affirmative action, yet these programmes are not universally welcomed among the public or the profession.

What is already known on this topic

Recent years have seen major initiatives in the UK to increase the size and broaden the demography of the medical student population

It is unclear whether the establishment of new training programmes such as graduate entry or foundation entry have widened access for groups traditionally under-represented in medicine, such as those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds

What this study adds

The graduate entry course programmes do not seem to be changing the socioeconomic profile of the UK medical student population

Though foundation programmes do increase the proportion of students from these groups, the numbers of places available are small and the acceptability of such “affirmative action” admission policies has been questioned

Contributors: This work was undertaken as an extension of the evaluation of the national expansion of medical schools project of which JP was principal investigator. JP and JM jointly conceived the idea for the current analyses. JP undertook the data cleaning and initial analyses and wrote the first draft, which was subsequently commented on substantially by JM. JLM and AS contributed to the analysis and interpretation of findings and revisions of the manuscript. JP and JM are guarantors.

Funding: This study was funded by the Department of Health Policy Research Programme and the Higher Education Funding Council for England (Evaluation of the National Expansion of Medical Schools project; No 0160056). The design and conduct of the research and analysis and interpretation of data was undertaken independently by the authors.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work, apart from that mentioned above; all authors are employed by the University of Birmingham, which admits graduate and undergraduate students to its medical programmes; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the West Midlands multi-centre research ethics committee (No 04 ⁄ MRE07⁄ 58).

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2011;341:d918

References

- 1.Cohen, J. The consequences of premature abandonment of affirmative action in medical school admissions. JAMA 2003;289:1143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.British Medical Association. The demography of medical schools: a discussion paper. BMA, 2004.

- 3.James D, Ferguson E, Powis D, Symonds I, Yates J. Graduate entry to medicine: widening academic and socio-demographic access. Med Educ 2008;42:294-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen J, Steinecke A. Building a diverse physician workforce. JAMA 2006;296:1135-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saha S, Guiton G, Wimmers PF, Wilkerson L. Student body racial and ethnic composition and diversity-related outcomes in US medical school. JAMA 2008;300:1203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Admissions to Higher Education Steering Group. Fair admissions to higher education: recommendations for good practice. Department of Education and Skills, 2004.

- 7.Seyan K, Greenhalgh T, Dorling D. The standardised admissions ratio for measuring widening participation in medical schools: analysis of UK medical school admissions by ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and sex. BMJ 2004;328:1545-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Secretary of State for Education. Medical schools: delivering the doctors of the future. Department for Education and Skills, 2004.

- 9.Panel on Fair Access to the Professions. Unleashing aspiration—the final report of the panel on fair access to the professions.Cabinet Office, 2009.

- 10.Parry JM, Mathers JM, Stevens A, Parsons A, Lilford R, Spurgeon P, et al. Admissions processes for five year medical courses at English schools: a review. BMJ 2006;332:1005-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Powis D, Hamilton J, Gordon J. Are graduate entry programmes the answer to recruiting and selecting tomorrow’s doctors? Med Educ 2004;38:1147-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rolfe IE, Ringland C, Pearson A-S. Graduate entry to medical school? Testing some assumptions. Med Educ 2004;38:778-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Searle J. Graduate entry medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. Med Educ 2004;38:1130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.St George’s, University of London. Why some students deserve special treatment. 2011. www.sgul.ac.uk/studying-at-st-georges/widening-participation/why-some-students-deserve-special-treatment.

- 15.University of Sheffield. Schools, colleges and community groups. 2011. www.shef.ac.uk/schools/soams.

- 16.British Medical Association. Equality and diversity in UK medical schools. BMA, 2009.

- 17.Garlick PB, Brown G. Widening participation in medicine. BMJ 2008;336:1111-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ip H, McManus, I. Increasing diversity amongst clinicians: is politically correct but is costly and lacks evidence to support it. BMJ 2008;336:1082-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dabbs TR. Widening participation in medicine—the flip side. BMJ 2011. www.bmj.com/cgi/eletters/336/7653/1111#195735.

- 20.UCAS. Managing applications to UK higher education courses. 2011. www.ucas.ac.uk/.

- 21.Office for National Statistics. The National Statistics socio-economic classification (NS-SEC). 2011. www.ons.gov.uk/about-statistics/classifications/current/ns-sec/index.html.

- 22.Howe A, Campion P, Searle J, Smith H. New perspectives—approaches to medical education at four new UK medical schools. BMJ 2004;329:327-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mathers J, Parry JM. “Older” mature students’ experiences of applying to study medicine in England: an interview study. Med Educ 2010;44:1084-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathers J, Parry JM. Why are there so few working-class applicants to medical schools? Learning from the success stories. Med Educ 2009;43:219-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Do PCT, Parry JM, Mathers J, Richardson M. Monitoring the widening participation initiative for access to medical school: are present measures sufficient? Med Educ 2006;40:750-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higher Education Funding Council for England. Widening participation: a review. HEFCE, 2006.

- 27.Directgov. University and higher education. 2011. www.aimhigher.ac.uk.

- 28.Carrasquillo O, Lee-Rey ET. Diversifying the medical classroom: is more evidence needed? JAMA 2008;300:1203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.James D, Yates J, Nicholson S. Comparison of A level and UKCAT performance in students applying to UK medical and dental schools in 2006: cohort study. BMJ 2010;349:c478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Higher Education Act 2004. Stationery Office, 2010.

- 31.Greenhalgh T, Seyan K, Boynton P. “Not a university type”: focus group study of social class, ethnic and sex differences in school pupils’ perceptions about medical school. BMJ 2004;328;1541-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.BBC News.Chancellor attacks Oxford admissions. 2000. May 26. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/education/764141.stm.

- 33.Poor students to be given two grade “head start” when applying for university places. Daily Mail 2009. August 10. www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1205360/Poor-students-given-grade-head-start-applying-university-places.html.

- 34.Six top A-levels, but snubbed by top universities. Was it because she went to a private school? Daily Mail 2009. August 22. www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1208192/Too-clever-half-Private-school-student-SIX-grade-As-A-levels-turned-away-university-applied-for.html.

- 35.Boursicot K, Roberts T. Widening participation in medical education: challenging elitism and exclusion. Higher Education Policy 2009;22:19-36. [Google Scholar]

- 36.The medical time bomb: “too many women doctors”. Independent 2 August 2004. www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/health-news/the-medical-timebomb-too-many-women-doctors-551149.html.

- 37.McKinstry B, Dacre J. Are there too many female medical graduates? BMJ 2008;336:748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]