Abstract

There are several examples of membrane-associated protein domains that target curved membranes. This behavior is believed to have functional significance in a number of essential pathways, such as clathrin-mediated endocytosis, which involve dramatic membrane remodeling and require the recruitment of various cofactors at different stages of the process. This work is motivated in part by recent experiments that demonstrated that the amphipathic N-terminal helix of endophilin (H0) targets curved membranes by binding to hydrophobic lipid bilayer packing defects which increase in number with increasing membrane curvature. Here we use state-of-the-art atomistic simulation to explore the packing defect structure of curved membranes, and the effect of this structure on the folding of H0. We find that not only are packing defects increased in number with increasing membrane curvature, but also that their size distribution depends nontrivially on the curvature, falling off exponentially with a decay constant that depends on the curvature, and crucially that even on highly curved membranes defects large enough to accommodate the hydrophobic face of H0 are never observed. We furthermore find that a percolation model for the defects explains the defect size distribution, which implies that larger defects are formed by coalescence of noninteracting smaller defects. We also use the recently developed metadynamics algorithm to study in detail the effect of such defects on H0 folding. It is found that the comparatively larger defects found on a convex membrane promote H0 folding by several kcal/mol, while the smaller defects found on flat and concave membrane surfaces inhibit folding by kinetically trapping the peptide. Together, these observations suggest H0 folding is a cooperative process in which the folding peptide changes the defect structure relative to an unperturbed membrane.

Introduction

The complex biochemistry that sustains the life of a eukaryotic cell requires compartmentalization. The boundaries of cells and of organelles within the cell are defined by membranes; the chemistry and material properties of a particular membrane are defined by the composition of lipids, sterols, and proteins. But apart from simply compartmentalizing the cellular and subcellular space, membranes are now understood to provide an essential platform for interfacial biochemistry, and therefore they play an essential part in signaling and trafficking pathways (1–4). Even more interestingly, it has become apparent that the shape of the membrane plays an important role in regulating these pathways, with certain proteins tending to aggregate on curved membranes (5,6), others that generate curved membranes (7–11), and with many performing both tasks in vitro.

A critical step in many signaling and transport pathways, such as clathrin-mediated endocytosis (1,4) and COPII vesicular trafficking (12), is the transient anchoring of proteins to the interface by amphipathic moieties—structural motifs that have both hydrophobic and hydrophilic character, and therefore partition naturally at the hydrophobic/hydrophilic interface within the membrane (13–15). Amphipathic moieties are also present in pathogenic peptides, such as α-synuclein (16,17), which in patients with Parkinson's disease assembles to form pathogenic aggregates (18). Therefore, the process by which amphipathic peptides associate with membranes is of direct relevance to a wide range of both normal and pathological conditions.

A few years ago, it was proposed that the amphipathic helix of α-synuclein (19) as well as that of ArfGAP1 (14) preferentially bind highly curved, negatively charged membranes by identifying lipid packing defects—locations on the membrane surface where, to accommodate high curvature, the hydrophobic interior of the membrane is exposed to the solvent. Very recently, it was suggested that, much like N-BAR domains, α-synuclein senses curved membranes (20), and folding of the N-terminal amphipathic segment is driven by high curvature vesicles (21). Using a novel assay that simultaneously measures liposome size and density of bound protein, it has just been demonstrated that the ability of the N-terminal helix (hereafter called “H0”) of endophilin (22) to sense curved membranes—even at saturating quantities of protein—is driven not by an increased affinity for lipid packing defects with curvature, but rather by the increasing number of such defects with curvature (5,6).

Other recent work has demonstrated the preference of the Epsin N-terminal homology (ENTH) domain (23,24) for highly curved membranes, using a fluorescence assay to show aggregation of ENTH on membrane tubules drawn by micropipette aspiration (25). The interrelation of curvature, packing defects, and amphipathic helix folding is clearly of great interest. Critical questions remain unanswered, however, such as the detailed structure of lipid bilayer defects, how their number and size depend on membrane curvature, and how exactly such defects modulate the folding of amphipathic helices.

In this regard, an “atom's eye view” of the membrane surface would be invaluable. Such a view is possible with a carefully designed series of simulations, which follow the protein, the membrane, and solvent in atomic detail. Studies of this kind have, for example, yielded insight into the deformation of membranes by N-BAR domain proteins (26–30). Here, following previous work in our group on membrane binding of endophilin (31), we have used state-of-the-art atomic-scale molecular dynamics simulation to study the defect structure of curved and flat membranes, as well as recently developed advanced sampling methods to study how such defects mediate folding of the H0 helix of endophilin at the interface of curved membranes. Our results directly demonstrate that the number of hydrophobic defects correlates positively with curvature, that the density of defects is significantly enhanced when the radius of curvature is comparable to that of a synaptic vesicle (∼40 nm), and that the likelihood of observing a particular defect decreases exponentially with the size of the defect, with a decay constant that decreases with increasing convexity. We also use metadynamics (32,33) to calculate the folding free energy of the H0 helix of endophilin (residues 1–22 of human endophilin A1, sequence MSVAGLKKQFHKATQKVSEKVG) on curved membranes presenting defects as well as flat and concave membranes presenting fewer and smaller defects. In the absence of defects, H0 in fact does not fold. In the presence of large defects, folding of H0 is favored by ∼3 kcal/mol, while in bulk solvent H0 folding is disfavored by ∼2 kcal/mol. On flat and concave membranes—where large defects are rare—we find that H0 binds the membrane in an unfolded configuration, becoming kinetically trapped and unable to find the folded amphipathic helix state. Importantly, our results are consistent with experimental observations by electron paramagnetic resonance of the insertion of H0, and with circular dichroism spectra on the helicity of H0, providing a verification of the simulation protocols and lending credence to our observations.

Our analysis of the defect structure of protein free membranes is, to our knowledge, the first direct observation of the dependence of defect structure on curvature, supports the hypothesis of Hatzakis et al. (5), and demonstrates, ostensibly, for the first time the nontrivial distribution of defect sizes. Our metadynamics calculations offer what we believe to be the first atomically detailed, unbiased view of the ensemble of H0 at curved membranes and support the idea that curvature promotes folding of H0. Furthermore, the fact that defects of sufficient size to accommodate the folded face of H0 are never observed in protein free membranes, even at high curvature, suggests that the folding process is a cooperative one, in which the folding H0 recruits defects—which an analysis of the size distribution demonstrates are noninteracting in the absence of protein. Finally, an analysis of the surface of the highly curved membrane with H0 folded shows that the packing defect area fraction is significantly less than the same membrane without protein, consistent with the idea that the protein binds the curved membrane to reduce the exposure of hydrophobic chains to solvent.

Methods

Molecular dynamics simulation details

All simulations were performed with NAMD 2.7b1 (34), using the CHARMM22 force field (35) with CMAP correction for protein-protein interaction, and the CHARMM27 force field (36) with CMAP correction for lipid-lipid and lipid-protein interactions. All membranes were mixtures of 30% DOPS and 70% DOPC lipids. No fixed random seed was used. The electrostatic interaction was calculated using the particle-mesh Ewald method (37). Heavy atom-hydrogen bonds were constrained by SHAKE/SETTLE algorithm (38,39). Simulations that were integrated under isothermal-constant volume conditions (constant NVT) were coupled to a thermal bath at 310 K via a Langevin thermostat (40) with damping coefficient of 0.5 ps−1 and an integration timestep of 1.8 fs. Simulations that were integrated under isothermal-isobaric conditions (constant NPT) did so via a Langevin barostat with piston period of 0.2 ps, damping frequency of 0.1 ps−1 (41).

The following details are for the protein-free membranes; details on the metadynamics calculations are found in the Supporting Material. For each system, 20,000 steps of conjugate-gradient minimization followed by gradually heating to 310 K were first performed. Data were collected for two independent flat membranes, equilibrated under NPT conditions for 15 ns, followed by production runs of 14 ns and 40 ns under NVT conditions. The curved membrane system was taken from a previous simulation (26) including an amphiphysin N-BAR protein; to create a standing-wave membrane the protein was removed but the box dimensions were fixed and the system was equilibrated for 20 ns under NVT conditions, followed by two separate production runs of ∼14 ns and 51 ns. In each case, the area per lipid equilibrated to between 63 and 64 Å2. Other authors have created curved membrane environments for simulation by introducing an asymmetry across the bilayer (42); here the bilayer is symmetric, mimicking curvature sensing experiments in vitro. The results are analyzed and visualized using the VMD package (43). The simulations were periodic in all directions.

Results and Discussion

Curvature and lipid packing defects are nontrivially related

If amphipathic helices are to preferentially bind curved membranes by recognizing lipid packing defects, then the distribution of such defects ought to depend on membrane curvature. We have therefore characterized this distribution by mapping lipid packing defects on the surface of both curved and flat membranes. The generation of the wrinkled membrane surface shown in Fig. 1 a requires some care; we did so without applying biasing forces to individual lipids (more details are found in Methods). Packing defects are identified by first mapping the surface of the hydrocarbon chains that are exposed to the solvent, and then projecting that surface onto the membrane midplane, and finally projecting the midplane into the xy plane, taking care to preserve the area of the projection. (The height of the membrane is denoted by z.) This procedure allows visualization of the packing defects on the surface of a curved membrane without distortion.

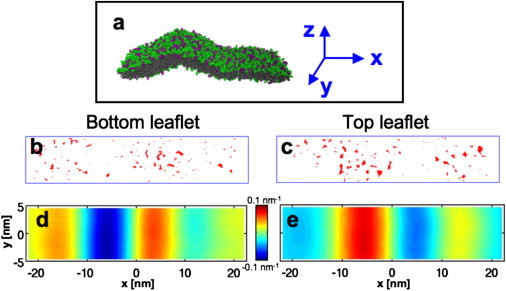

Figure 1.

(a) A configuration of the protein-free membrane, with a region of high curvature imposed by the boundary conditions. At the region of highest curvature, the membrane has a radius of curvature of roughly 11 nm. (b) Red regions indicate packing defects in the bottom leaf of the membrane patch at one instant, mapped as described in Methods. (c) Packing defect structure of the top leaflet. (d) Curvature of the bottom leaflet, indicated by the color scale bar between panels d and e. (e) Curvature of the top leaflet.

Fig. 1, b and c, shows the projections of the packing defects in the top and bottom leaflets of the curved membrane patch, as observed at a particular moment of the simulation. A distribution of sizes is apparent, as is a nontrivial spatial distribution of defects. The curvature at each point on a surface is defined by a pair of scalar quantities (44,45); at each point on the surface, imagine a pair of orthogonal tangent circles; the curvatures are the inverses of the circles' radii. In our case, however, we are interested in curvature on length-scales at and beyond the size of an N-BAR domain. On these length-scales, our membrane is well described by curvature along a single direction (or equivalently radius); this is what is presented in Fig. 1, d and e. (More details are found in the Supporting Material.) The curvature of the membrane ranges from a highly curved region, where the radius corresponds to roughly 11 nm at the membrane midplane, to regions that are essentially flat. We have defined the sign of the curvature to indicate whether the leaflet is on the convex or concave side of a bend, with positive curvatures corresponding to convex surfaces and negative values corresponding to concave surfaces. Comparing panels 1 b and 1 c with panels 1 d and 1 e, it is clear that more and larger defects are observed in regions with large convex curvature.

Although the data in Fig. 1 are suggestive, we cannot draw definitive conclusions based on the configuration of the bilayer at a single instant in time; rather, we must compile statistics on the frequency and size of packing defects from many such configurations. Each point in Fig. 2 a is a unique packing defect—nearly 24,000 in all—plotted to show the dependence of the area of packing defects on curvature. (Details on how defects and curvature were measured are in Supporting Methods in the Supporting Material.) It is clear that the area of the largest defects increases with increasingly convex leaflets, and decreases as a leaflet becomes more and more concave. There also appears to be many more defects of modest size—above 0.2 nm2—at and above curvatures of 0.02 nm−1, which corresponds to a 50-nm radius tubule.

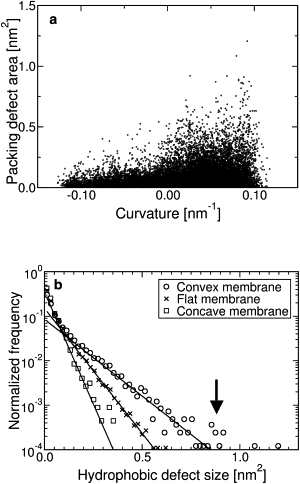

Figure 2.

(a) Scatter plot showing relation between defect area and local curvature of the membrane. Each point is a single defect. (b) Histogram of defect areas for convex, flat, and concave membranes (symbols). Solid lines are least-squares fits to an exponential decay, decay constants in units of nm−2 are 7.3 (convex membrane), 12.8 (flat membrane), and 18.9 (concave membrane).

Packing defect size distribution

If the defects are placed into a histogram based on their area as in Fig. 2 b, we observe distinct differences in the frequency of defects as a function of their area for three different cases: very convex leaflets (curvature > 0.02 nm−1, the curvature on the outer leaflet of a 100 nm diameter liposome), flat leaflets (amplitude of curvature < 0.01 nm−1), and very concave leaflets (curvature <−0.02 nm−1, the curvature on the inner leaflet of a 100-nm-diameter liposome). There is a systematic dependence on curvature, with both the fractional area occupied by defects (p, probability of observing a defect, in Table 1) and the likelihood of observing large defects increasing with convexity, which extends in our data curvatures of 0.1 nm−1, or the curvature of a 20-nm-diameter tubule, on the order of the diameter of the necks budding endocytotic vesicles. This trend is reflected in the median packing defect area of each distribution: 0.26 nm2 for the highly concave membrane, 0.34 nm2 for the flat membrane, and 0.45 nm2 for the convex membrane. Furthermore, the data for all three cases appear to follow an exponential decay C exp (−αx), with a decay constant that increases as the membrane goes from convex to concave. The decay constants α were estimated by a logarithmic transformation of the dependent variable, then fitting all three data sets by linear regression. The decay constants (in units of nm−2) so determined are 7.3 (convex membrane), 12.8 (flat membrane), and 18.9 (concave membrane).

Table 1.

Packing defect area fraction (p), defect area distribution predicted by the percolation model (αperc), and measured in simulations αmeas

| p | αperc [nm−2] | αmeas [nm−2] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Convex | 0.040 | 7.9 ± 0.4 | 7.3 ± 0.3 |

| Flat | 0.012 | 13.3 ± 0.7 | 12.8 ± 0.4 |

| Concave | 0.003 | 18.1 ± 0.4 | 18.9 ± 1.5 |

| H0 folded | 0.018 | N/A | N/A |

The errors are standard deviations, as described in the Supporting Material. The area fraction for the membrane surface with H0 folded is also included; in this case, the percolation analysis is not relevant.

More details on the fit (including the goodness of fit) are found in Supporting Methods in the Supporting Material. According to these data, observing a defect of a specified size on a convex membrane is ∼140 times more likely than observing the same defect on a flat membrane, and about a million times more likely than on a convex membrane patch. Also worth noting is that there appears to be a second exponential decay in the large defect size region of the convex data. (See arrow in Fig. 2 b.) There is very likely a fourth distribution at the highest curvature values; our data, however, do not provide sufficient statistics to make any definitive statements about this regime. A critical question is, however, is how these observations are related to the membrane-mediated folding of the H0 helix of an N-BAR domain containing protein such as endophilin. The hydrophobic face of H0 presents an area of roughly 6 nm2 when folded, while the absolute largest packing defect we observed had an area of ∼1.2 nm2. This issue will be addressed in more detail later.

Packing defects are noninteracting in the absence of protein

It is also possible to provide an explanation for the exponential decay of the defect size distribution. The simplest model is one in which, at each moment, any given area on the membrane is either occupied by a defect (with probability p) or it is not occupied (with probability of 1−p). Such percolation models have been studied for many years in the math and physics literature so that many exact results are known, and these models have found successful application in many disciplines (46). Here, we can measure the probability p directly from our data; it is the average fraction of the membrane area that is occupied by defects. In our case, p is well below the critical probability, and the defect size distribution is easily calculated by a simple Monte Carlo calculation. (See the Supporting Material for details on the Monte Carlo calculation.) Note that because p is an observed quantity, it is not an adjustable parameter in this analysis. The only adjustable parameter is the lattice spacing of the of the Carlo calculation, and we find that all three sets of data (defect distributions for convex, flat, and concave membrane surfaces) are predicted well by a single lattice spacing, as shown in Table 1 and Fig. S1. We therefore suggest that this offers strong evidence that the defect distribution is well described as a percolation phenomenon below the critical percolation probability. The ramifications of this observation are described in the Summary and Conclusions. In the next section, we consider how the packing defect structure of the membrane impacts the folding of H0.

Folding of the H0 helix of endophilin is mediated by packing defects

Here we present rigorous biased molecular-dynamics calculations of the folding of H0 in four different environments: In bulk solvent; at the surface of a convex membrane; at the surface of a flat membrane; and at the surface of a concave membrane. Ambitious calculations of this kind have only recently become tractable thanks to the development of the metadynamics method (32,33), which—given a suitable reaction coordinate—accelerates the sampling of rugged free-energy landscapes. Suitable reaction coordinates are already known for studying the folding of α-helices, as demonstrated recently in a metadynamics study of ATP-dependent folding of the DB loop of actin (47) and a calculation that involved the folding of a transmembrane helix (48).

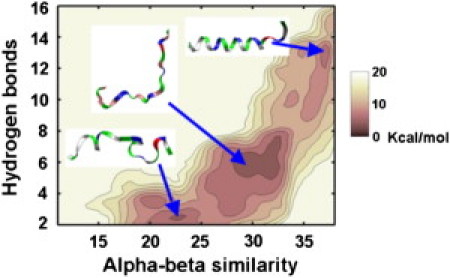

We first present the folding landscape for H0 (residues 1–22 of human endophilin A1) in bulk solvent (0.015 mol NaCl) in Fig. 3. A brief explanation of the coordinates is in order. The α-helical state is identified by a pair of coordinates: The number of 1–4 amide nitrogen-carbonyl oxygen hydrogen bonds, and a backbone torsion metric that measures similarity to α-helical Ramachandran angles (see the Supporting Material). The result of a metadynamics calculation is a free energy surface or two-dimensional potential of mean force (PMF) in the space defined by these two coordinates. In each of the PMFs presented below, the folded, α-helical state is in the upper-right corner, maximizing 1–4 hydrogen bonds and α-similarity. In the data presented in Fig. 3, multiple folding/unfolding transitions were observed beginning from an unfolded configuration, providing some confidence that the data are well converged. It is clear from the PMF that in bulk solvent the most stable configurations for H0 are unfolded. While the α-helical state is visited several times over the course of the simulation, it is metastable relative to the unfolded states by 2 kcal/mol. These data are consistent with previous experiments using electron paramagnetic spectroscopy (49) and circular dichroism spectroscopy (6). In this context, consistency with prior experimental data serves to validate our approach and provides confidence to undertake a more interesting and important calculation—folding of H0 in the presence of the membrane.

Figure 3.

Two-dimensional potential of mean force for folding H0 in bulk solvent. Each locally stable basin is illustrated by a ribbon representation image of a typical configuration. The most stable state is the center of the three basins, thermodynamically favored by 2 kcal/mol over the α-helical state. (The peptides are color-coded throughout the article as follows: red, negatively charged residue; blue, positively charged residue; green, polar residue; white, hydrophobic residue.)

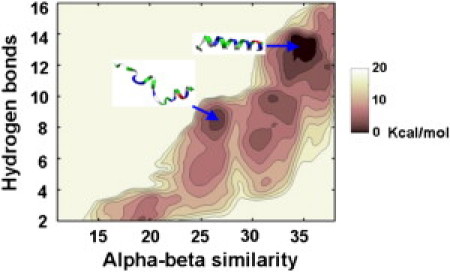

To study the influence of the local membrane curvature on the free energy surface of H0 folding, we performed well-tempered metadynamics to sample the same PMF presented in Fig. 3, but this time at three different locations on the curved membrane corresponding to: very convex curvature; no curvature; and very concave curvature. (Details are found in the Supporting Material.) Of these three calculations, only the sampling of the folding PMF in the presence of the very convex membrane (Fig. 4) was well enough converged to draw quantitative conclusions. (See Fig. S2 and related discussion for data on the convergence.) In this case, the folded state was favored by 3 kcal/mol over the next most stable, unfolded state, and two metastable, partially folded or unfolded states were observed. The annotated metastable state that is closest to the global minimum, folded state is suggestive—one turn of the helix has been formed (at the C-terminal end), and two neighboring hydrophobic residues (Val17 and Val21) are in contact with a hydrophobic packing defect. The hydrophobic area presented by these two Val side chains is small enough to select a defect that, while rare in the defect population on the convex membrane, is extremely rare on a flat membrane and virtually nonexistent on a concave membrane. Given the data in Fig. 2, it seems plausible that the cooperative process involves a mutual stabilization—a defect stabilizes a turn of helix, and the helix stabilizes the defect. The helix folding is then propagated when the defect fluctuates to a larger size, stabilizing the next turn of helix, and so on.

Figure 4.

Two-dimensional potential of mean force for folding H0 at a convex membrane surface. The significantly larger packing defects found at a convex membrane surface promote folding of H0—now the α-helical state is favored over the unfolded states by 3 kcal/mol. The peptide color-coding is explained in the caption to Fig. 3.

H0 folding radically changes the defect distribution

For the peptide at the surface of a flat or concave membrane, folding is either thermodynamically disfavored sufficiently strongly that we do not observe it (even with the help of a state-of-the-art free energy sampling algorithm), or the peptide becomes bound to the membrane in such a way that folding becomes kinetically frustrated. (The PMF obtained for a much smaller flat membrane patch, which is amenable to much more extensive sampling, also does not converge.) Considering that the PMF was well converged in bulk solvent, despite the fact that the folded state was disfavored, points to the latter explanation as being more likely. Indeed, the sample of configurations observed for H0 on the flat and negatively curved membranes is telling—in each case, the peptide is bound to the membrane by a few hydrophobic side chains at the N-terminal end in contact with small, independent defects. Typical configurations for these cases are shown in Figs. 5 and 6. The key difference between the configurations sampled in these systems and those sampled on the highly convex membrane is that, in these cases, the population of defects large enough to stabilize a turn of the helix is vanishingly small, and therefore there is no additional thermodynamic force from the membrane to drive folding toward a fully helical state.

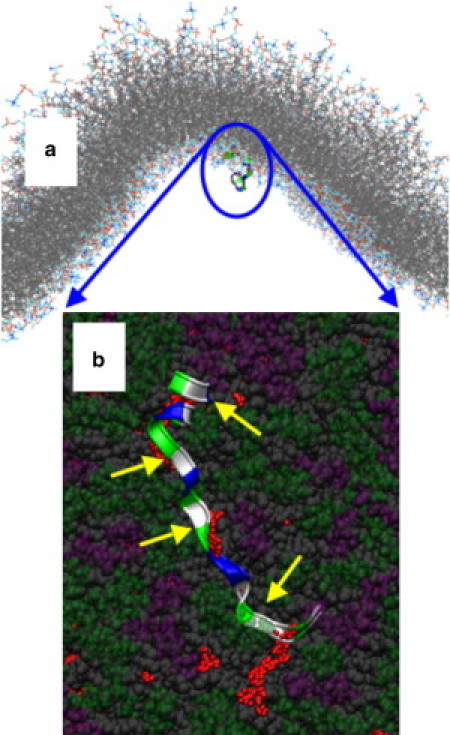

Figure 5.

Example of a kinetically trapped configuration at a convex membrane surface. (a) Position of H0 from afar; note its position near the region of maximum concave curvature. (b) Detail of how H0 binds membranes presenting mostly small defects. (The hydrocarbon chains of the lipids are rendered in space-filling representation: gray, hydrocarbon chains; purple, PS headgroups; green, PC headgroups.) Portions of the hydrocarbon chains that would be exposed to solvent if not for the peptide (small red spheres), calculated as described in Supporting Methods in the Supporting Material. (Yellow arrows) Hydrophobic residues in contact with packing defects.

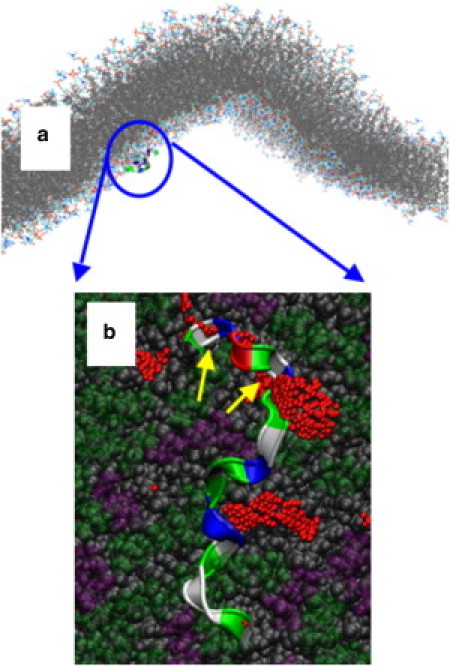

Figure 6.

Example of a kinetically trapped configuration at a flat membrane surface. (a) Position of H0 from afar, note its position at a region of near-zero curvature. (b) A detail of the peptide binding is shown; note the larger size of the packing defects compared to the concave membrane. See Fig. 5 legend for an explanation of the rendering.

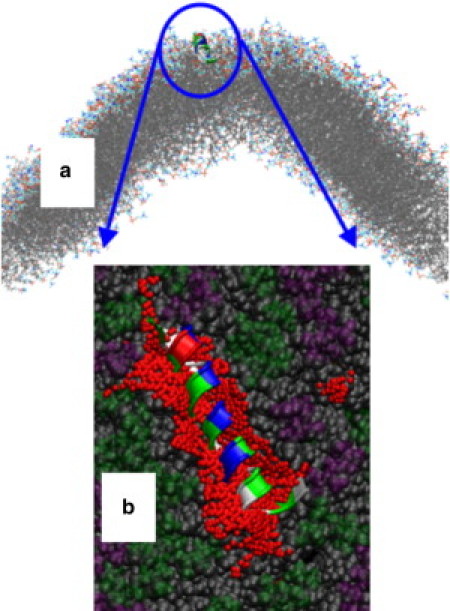

Recall from the discussion around Fig. 2 that, relative to convex membrane surfaces, defects of ∼0.5 nm2 are rare on flat membrane surfaces, rarer still on concave membrane surfaces, and that a defect of area sufficient to accommodate the folded, hydrophobic face of H0 (6 nm2) was never observed. Fig. 7 shows in detail how H0 looks when stably folded on a convex membrane; note that once bound the peptide covers what would otherwise be an extensive hydrophobic defect, sufficient in size to accommodate the hydrophobic face of H0. Because defects of this size are never observed in the absence of H0, the peptide must be driving the defect structure of the membrane, just as the membrane is driving the structure of the peptide. Indeed, we repeated the analysis of the defect structure of the highly curved membrane, this time including the peptide in the analysis as part of the membrane. We found first that the fractional area occupied by defects is significantly decreased relative to protein free membranes, by more than a factor of 2 (Table 1). Furthermore, the packing defect distribution with H0 folded was not well described by an exponential decay, indicating that in the presence of H0 defects are no longer described by a percolation model, and are therefore correlated. This leads us to suggest a cooperative peptide-membrane folding process, initiated by a defect arising from the membrane curvature.

Figure 7.

Example of H0 stably folded at a convex membrane surface. (a) Position of H0 near the region of maximum convex curvature. (b) A detail of the membrane binding of H0 on a large defect encountered at a convex membrane surface. Note the large hydrophobic surface that is in contact with the peptide, sufficient to accommodate the hydrophobic face of H0 when folded. Rendering colors explained in the caption to Fig. 5.

Our data offer an atomic-level view of the defect structure of the membrane, and provide insight into how curved membranes recruit amphipathic helices, at a level of detail that is presently not experimentally accessible. Our confidence in the conclusions drawn from these results is increased through a direct comparison between some simulated observables and their experimental counterparts. It was mentioned previously that in our calculations in bulk solution, the H0 peptide favors unfolded states, as observed by both electron paramagnetic resonance (49) and circular dichroism (CD) (6,49) spectroscopy. In Fig. S3 a we have quantified this observation by predicting from our samples of H0 in bulk solvent and on a convex membrane the CD spectra that would be observed.

Theoretical advances in the last decade have enabled the accurate calculation of CD spectra for a system of this size (50–52)—provided a high quality sample of the equilibrium ensemble is obtained. This comparison therefore provides a direct test of whether we can have confidence in the ensemble of calculated structures and corresponding PMFs. Importantly, the data in Fig. S3 a are consistent with CD spectra presented in Bhatia et al. (6) that indicate that H0 is helical in the presence of liposomes. By incorporating spin labels at different positions along the sequence of H0, it is also possible by electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy to measure the depth of insertion of each residue into the bilayer (49). As a further test of our calculations, we computed the same observable, shown in Fig. S3 b. Again, comparison with the experimental data presented in Gallop et al. (49) demonstrates that the ensemble of configurations sampled by our metadynamics calculation is representative of the ensemble observed experimentally.

Summary and Conclusions

Using atomically detailed molecular-dynamics simulation, we have mapped the hydrophobic packing defect structure of membranes as a function of curvature, finding that both the number and the area distribution of packing defects depends strongly on curvature, with the density and typical size of defects dramatically enhanced at curvatures (∼0.1 nm−1) characteristic of the necks of budding endocytotic vesicles. At all curvatures, on protein free membranes, the area distribution of packing defects decreases exponentially, with a decay constant that depends on curvature. We furthermore find that the data are explained well by a simple site percolation model, in which any location on the membrane is either occupied by a defect with probability p, or not, with a probability of 1−p. The ramification of this observation is that packing defects are noninteracting—the likelihood that any particular region on the membrane has a packing defect is simply p, independent of any other region. Therefore, large defects are simply smaller defects that happen to be neighbors.

To our knowledge, this is the first direct test of the hypothesis that packing defects are increased in number by curvature—an assumption that underlies the hypothesis that amphiphilic helices sense curvature by identifying such defects (5,6,14). Our data also support the hypothesis presented in Hatzakis et al. (5) that at saturating concentrations amphipathic moieties sense curvature not by increased affinity for defects but by an increased number of packing defects at high curvature. However, we provide the additional insight that the population of such defects that are of sufficient size to nucleate folding of H0 is dramatically enhanced by curvature. On flat and concave membrane surfaces packing defects are observed, but the vast majority are too small and their density too low to promote folding of H0. In the presence of such defects, H0 binds in an unfolded configuration, becoming kinetically trapped and unable to find the α-helical state. It is essential to point out, however, that even on highly curved membranes we do not observe any defects large enough to accommodate the hydrophobic face of H0 when already fully folded. We conclude that the folding and binding process must therefore be a cooperative one, in which the folding of the peptide H0 helix and the stabilization of a hydrophobic defect proceed in tandem. The fact that the distribution of defect sizes is well described by a simple percolation model supports the idea of a cooperative folding process, because the folding protein must drive smaller defects to coalesce into an area sufficient to accommodate the hydrophobic face of the protein. Once folded, the protein-membrane system presents a much smaller defect area to the solvent. Our observations are of relevance not only to ENTH domain membrane binding, but also the binding of other proteins containing amphipathic helical moieties, such as α-synuclein.

Apart from sensing membrane curvature, BAR and ENTH domains are known to remodel liposomes into high curvature vesicles, tubules, and reticulated structures (7–10,22,53). Of great current interest is the mechanism by which these proteins achieve this behavior, which is the subject of both theoretical (26,53–59) and experimental (11,22,49,60) work. Our data on the distribution of defect sizes together with the observation that there is a threshold defect size of ∼0.5 nm2, below which packing defects do not promote folding, suggest that in order for the hydrophobic insertion mechanism to be an effective means of remodeling, there must either 1), already be an area of positive curvature to promote amphipathic helix folding, or 2), the concentration of amphipathic moieties must be greatly enhanced over physiological concentrations, such that the rare defects large enough to promote folding are discovered by an amphipathic peptide. Indeed, tubulation experiments are performed at extremely high concentration (20 μM, for example), and recently evidence has been presented that an F-BAR-containing protein, FCHo—which lacks an obvious amphipathic insert—initiates the formation of clathrin-coated pits (61), beginning the process of membrane deformation where the membrane is initially flat.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Gary Ayton for discussions about computing curvature and his invaluable input in general.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant No. R01-GM063796). The computations were carried out from a grant of supercomputing time through the TeraGrid program of the National Science Foundation and were performed on Ranger at the Texas Advanced Computing Center and Kraken at the National Institute for Computing Sciences.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Slepnev V.I., De Camilli P. Accessory factors in clathrin-dependent synaptic vesicle endocytosis. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2000;1:161–172. doi: 10.1038/35044540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McMahon H.T., Gallop J.L. Membrane curvature and mechanisms of dynamic cell membrane remodelling. Nature. 2005;438:590–596. doi: 10.1038/nature04396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimmerberg J., Kozlov M.M. How proteins produce cellular membrane curvature. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:9–19. doi: 10.1038/nrm1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doherty G.J., McMahon H.T. Mechanisms of endocytosis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009;78:857–902. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.081307.110540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hatzakis N.S., Bhatia V.K., Stamou D. How curved membranes recruit amphipathic helices and protein anchoring motifs. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009;5:835–841. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhatia V.K., Madsen K.L., Stamou D. Amphipathic motifs in BAR domains are essential for membrane curvature sensing. EMBO J. 2009;28:3303–3314. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farsad K., Ringstad N., De Camilli P. Generation of high curvature membranes mediated by direct endophilin bilayer interactions. J. Cell Biol. 2001;155:193–200. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200107075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ford M.G.J., Mills I.G., McMahon H.T. Curvature of clathrin-coated pits driven by epsin. Nature. 2002;419:361–366. doi: 10.1038/nature01020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peter B.J., Kent H.M., McMahon H.T. BAR domains as sensors of membrane curvature: the amphiphysin BAR structure. Science. 2004;303:495–499. doi: 10.1126/science.1092586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frost A., Perera R., Unger V.M. Structural basis of membrane invagination by F-BAR domains. Cell. 2008;132:807–817. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jao C.C., Hegde B.G., Langen R. Roles of amphipathic helices and the Bin/Amphiphysin/Rvs (BAR) domain of endophilin in membrane curvature generation. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:20164–20170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.127811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee M.C.S., Orci L., Schekman R. Sar1p N-terminal helix initiates membrane curvature and completes the fission of a COPII vesicle. Cell. 2005;122:605–617. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hristova K., Wimley W.C., White S.H. An amphipathic α-helix at a membrane interface: a structural study using a novel x-ray diffraction method. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;290:99–117. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drin G., Casella J.-F., Antonny B. A general amphipathic α-helical motif for sensing membrane curvature. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:138–146. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernández-Vidal M., Jayasinghe S., White S.H. Folding amphipathic helices into membranes: amphiphilicity trumps hydrophobicity. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;370:459–470. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jao C.C., Der-Sarkissian A., Langen R. Structure of membrane-bound α-synuclein studied by site-directed spin labeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:8331–8336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400553101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jao C.C., Hegde B.G., Langen R. Structure of membrane-bound α-synuclein from site-directed spin labeling and computational refinement. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:19666–19671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807826105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spillantini M.G., Schmidt M.L., Goedert M. Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature. 1997;388:839–840. doi: 10.1038/42166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nuscher B., Kamp F., Beyer K. Alpha-synuclein has a high affinity for packing defects in a bilayer membrane: a thermodynamics study. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:21966–21975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401076200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Middleton E.R., Rhoades E. Effects of curvature and composition on α-synuclein binding to lipid vesicles. Biophys. J. 2010;99:2279–2288. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.07.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bartels T., Ahlstrom L.S., Beyer K. The N-terminus of the intrinsically disordered protein α-synuclein triggers membrane binding and helix folding. Biophys. J. 2010;99:2116–2124. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masuda M., Takeda S., Mochizuki N. Endophilin BAR domain drives membrane curvature by two newly identified structure-based mechanisms. EMBO J. 2006;25:2889–2897. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Camilli P., Chen H., Brunger A.T. The ENTH domain. FEBS Lett. 2002;513:11–18. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03306-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Itoh T., Koshiba S., Takenawa T. Role of the ENTH domain in phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate binding and endocytosis. Science. 2001;291:1047–1051. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5506.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Capraro B.R., Yoon Y., Baumgart T. Curvature sensing by the epsin N-terminal homology domain measured on cylindrical lipid membrane tethers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:1200–1201. doi: 10.1021/ja907936c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blood P.D., Voth G.A. Direct observation of Bin/Amphiphysin/Rvs (BAR) domain-induced membrane curvature by means of molecular dynamics simulations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:15068–15072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603917103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blood P.D., Swenson R.D., Voth G.A. Factors influencing local membrane curvature induction by N-BAR domains as revealed by molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys. J. 2008;95:1866–1876. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.121160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arkhipov A., Yin Y., Schulten K. Four-scale description of membrane sculpting by BAR domains. Biophys. J. 2008;95:2806–2821. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.132563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yin Y., Arkhipov A., Schulten K. Simulations of membrane tubulation by lattices of amphiphysin N-BAR domains. Structure. 2009;17:882–892. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arkhipov A., Yin Y., Schulten K. Membrane-bending mechanism of amphiphysin N-BAR domains. Biophys. J. 2009;97:2727–2735. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.08.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cui H., Ayton G.S., Voth G.A. Membrane binding by the endophilin N-BAR domain. Biophys. J. 2009;97:2746–2753. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laio A., Parrinello M. Escaping free-energy minima. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:12562–12566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202427399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barducci A., Bussi G., Parrinello M. Well-tempered metadynamics: a smoothly converging and tunable free-energy method. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008;100:020603. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.020603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phillips J.C., Braun R., Schulten K. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacKerell A.D., Bashford D., Ha S. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1998;102:3586–3616. doi: 10.1021/jp973084f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feller S.E., MacKerell A.D. An improved empirical potential energy function for molecular simulations of phospholipids. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2000;104:7510–7515. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Essmann U., Perera L., Pedersen L.G. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;103:8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryckaert J.-P., Ciccotti G., Berendsen H.J.C. Numerical integration of the Cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of N-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 1977;23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miyamoto S., Kollman P.A. SETTLE: an analytical version of the SHAKE and RATTLE algorithm for rigid water models. J. Comput. Chem. 1992;13:952–962. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grest G.S., Kremer K. Molecular dynamics simulation for polymers in the presence of a heat bath. Phys. Rev. A. 1986;33:3628–3631. doi: 10.1103/physreva.33.3628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feller S.E., Zhang Y., Brooks B.R. Constant pressure molecular dynamics simulation: the Langevin piston method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;103:4613–4621. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meyer G.R., Gullingsrud J., Martinac B. Molecular dynamics study of MscL interactions with a curved lipid bilayer. Biophys. J. 2006;91:1630–1637. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.080721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. 27–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Helfrich W. Elastic properties of lipid bilayers: theory and possible experiments. Z. Naturforsch. C. 1973;28:693–703. doi: 10.1515/znc-1973-11-1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kreyszig, E. 1991. Differential Geometry. Dover, Mineola, NY.

- 46.Grimmett G. 2nd Ed. Springer; Berlin, Germany: 1991. Percolation. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pfaendtner J., Branduardi D., Voth G.A. Nucleotide-dependent conformational states of actin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:12723–12728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902092106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gangupomu V.K., Abrams C.F. All-atom models of the membrane-spanning domain of HIV-1 gp41 from metadynamics. Biophys. J. 2010;99:3438–3444. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.09.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gallop J.L., Jao C.C., McMahon H.T. Mechanism of endophilin N-BAR domain-mediated membrane curvature. EMBO J. 2006;25:2898–2910. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Besley N.A., Hirst J.D. Theoretical studies toward quantitative protein circular dichroism calculations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:9636–9644. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hirst J.D., Bhattacharjee S., Onufriev A.V. Theoretical studies of time-resolved spectroscopy of protein folding. Faraday Discuss. 2003;122:253–282.. doi: 10.1039/b200714b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sreerama N., Woody R.W. Computation and analysis of protein circular dichroism spectra. Methods Enzymol. 2004;383:318–351. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)83013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ayton G.S., Lyman E., Voth G.A. New insights into BAR domain-induced membrane remodeling. Biophys. J. 2009;97:1616–1625. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zimmerberg J., McLaughlin S. Membrane curvature: how BAR domains bend bilayers. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:R250–R252. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Campelo F., McMahon H.T., Kozlov M.M. The hydrophobic insertion mechanism of membrane curvature generation by proteins. Biophys. J. 2008;95:2325–2339. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.133173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Löw C., Weininger U., Balbach J. Structure and dynamics of helix-0 of the N-BAR domain in lipid micelles and bilayers. Biophys. J. 2008;95:4315–4323. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.134155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ayton G.S., Blood P.D., Voth G.A. Membrane remodeling from N-BAR domain interactions: insights from multi-scale simulation. Biophys. J. 2007;92:3595–3602. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.101709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Khelashvili G., Harries D., Weinstein H. Modeling membrane deformations and lipid demixing upon protein-membrane interaction: the BAR dimer adsorption. Biophys. J. 2009;97:1626–1635. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ayton G.S., Lyman E., Voth G.A. Hierarchical coarse-graining strategy for protein-membrane systems to access mesoscopic scales. Faraday Discuss. 2010;144:347–357. doi: 10.1039/b901996k. discussion 445–481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fernandes F., Loura L.M.S., Prieto M. Role of helix 0 of the N-BAR domain in membrane curvature generation. Biophys. J. 2008;94:3065–3073. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.113118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Henne W.M., Boucrot E., McMahon H.T. FCHo proteins are nucleators of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Science. 2010;328:1281–1284. doi: 10.1126/science.1188462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.