Abstract

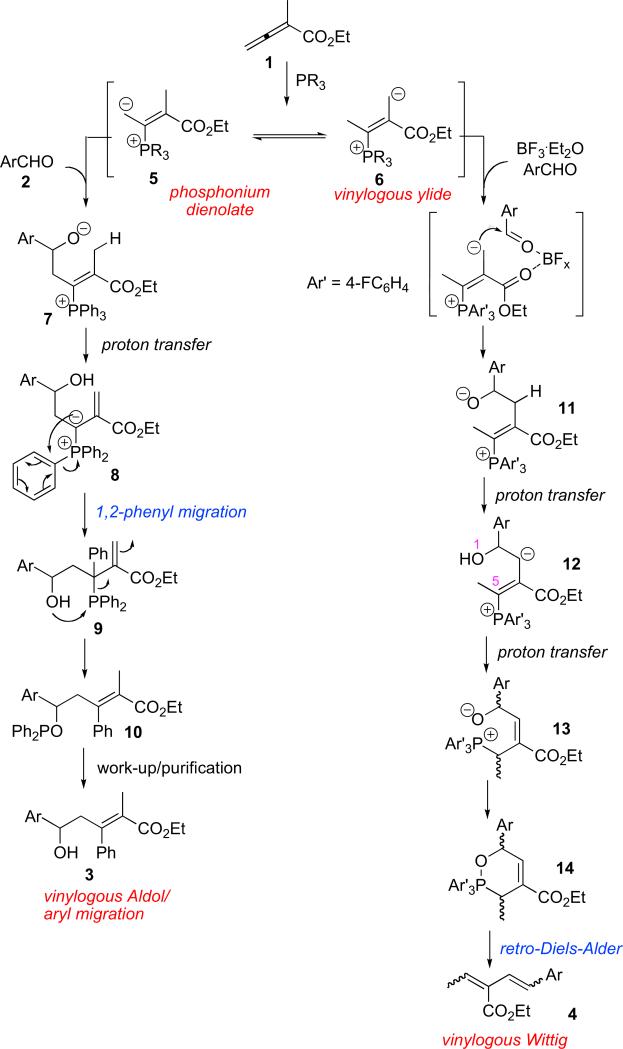

This paper describes the equilibrium established between a phosphonium dienolate zwitterion and a vinylogous phosphorus ylide, and their reactions with aldehydes. The reactions between ethyl 2-methyl-2,3-butadienoate and various aldehydes occur through either a phosphonium dienolate or a vinylogous ylide intermediate, depending on the presence/absence of a Lewis acid and the nature of the phosphine. We observed a rare vinylogous Wittig olefination from the reaction between ethyl 2-methyl-2,3-butadienoate and an electron-deficient aromatic aldehyde in the presence of a stoichiometric amount of an electron-deficient triarylphosphine and a catalytic amount of a Lewis acid (e.g., BF3·Et2O). On the other hand, the use of triphenylphosphine, in the absence of a Lewis acid, facilitated vinylogous aldol addition, accompanied by a rare 1,2-aryl phosphorus-to-carbon migration.

Keywords: Phosphine, Allenoate, Phosphonium dienolate, Vinylogous ylide, Vinylogous Wittig, Vinylogous aldol

1. Introduction

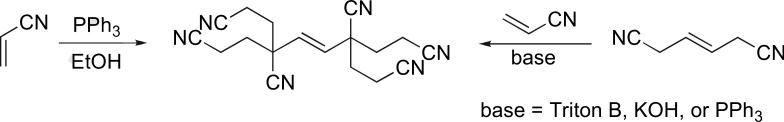

In 1962, Takashina and Price, while studying the nucleophilic polymerization of electron-poor olefins,1 reported the formation of a crystalline hexameric adduct of acrylonitrile when they used triphenylphosphine as a catalyst in alcoholic solvents.2 Because the same product could be prepared through the reaction of 1,4-dicyano-trans-2-butene with acrylonitrile in the presence of a base, the initial dimerization of acrylonitrile to 1,4-dicyano-trans-2-butene was proposed as the key step (Scheme 1). This tail-to-tail dimerization would, however, be a very unlikely event in conventional base-catalyzed polymerization. Consequently, Price invoked the formation of an ylide intermediate B from the immediate zwitterionic intermediate A to explain the reaction sequence of acrylonitrile hexamerization (Scheme 2).

Scheme 1.

Hexamerization of acrylonitrile catalyzed by triphenylphosphine.

Scheme 2.

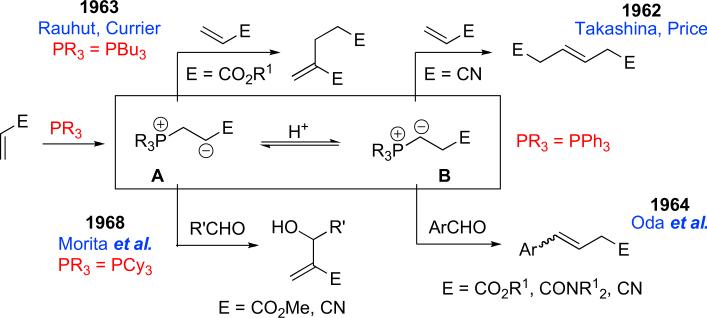

A quick history of phosphine-catalyzed/mediated reactions of the 1960s.

Shortly after the proposal of the ylide B as an alternative intermediate derived from zwitterion A, Rauhut and Currier successfully trapped the enolate A (E=CO2R1) in the synthesis of dialkyl 2-methyleneglutarates from alkyl acrylates when using tributylphosphine as the nucleophilic catalyst.3 The following year (1964), Oda and co-workers succeeded in trapping ylide B with an aromatic aldehyde, using triphenylphosphine as the nucleophilic trigger in alcoholic solvents.4 The resulting transformation was a Wittig olefination. Although not catalytic with respect to the phosphine, this transformation was the first phosphine-mediated reaction between an olefin and an aldehyde. One interesting feature in Oda's experiment was that the ylide was generated in situ directly from a phosphine and an activated olefin in the presence of an aldehyde, rather than from a preformed phosphonium salt. In 1968, Morita and co-workers reacted the enolate A with an aldehyde, creating a novel aldol-type product.5 Credit was granted to Morita, together with Baylis and Hillman,6 for efficiently trapping the enolate A in the first phosphine-catalyzed aldol-type reaction. Notably, electron-donating trialkylphosphines preferred forming (and/or facilitated the reactions of) intermediate A, whereas electron-deficient triarylphosphines favored the ylide intermediate B.7 The greater electron-withdrawing nature of triarylphosphines (relative to trialkylphosphines) is believed to be responsible for the formation of the ylide B, i.e., stabilizing the α-anion. In addition, alcoholic solvents were indispensable for facilitating the conversion of the enolate A to the ylide B via proton transfer steps.

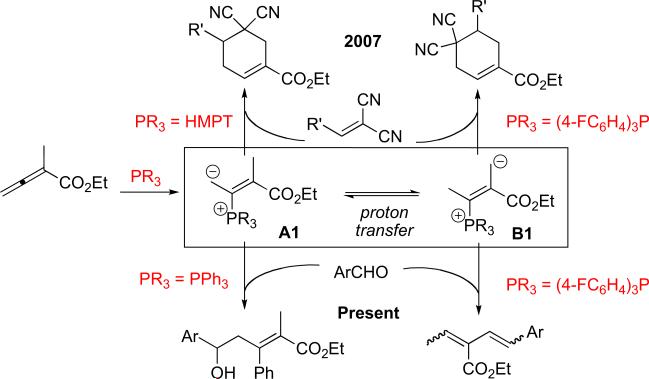

While the Morita–Baylis–Hillman (MBH)-type of reaction modality has continued to garner attention from the organic synthesis community,8 especially during the last two decades,9 the intricate equilibrium between the phosphonium enolate A and ylide B or reactions proceeding through the ylide intermediate B have been observed only recently.10 In 2007, we reported the equilibrium between the phosphonium dienolate (vinylogous enolate) A1 and the alternative extended ylide (vinylogous ylide) B1 and their reactions with activated olefins to form two regioisomeric cyclohexenes (Scheme 3).11 In agreement with Price's and Rauhut and Currier's observations, the electron-donating/nucleophilic12 hexamethylphosphorous triamide (HMPT) favored the reaction through the phosphonium enolate A1, whereas electron-deficient triarylphosphines facilitated reactions proceeding through the vinylogous ylide B1.5 Based on the reactions of intermediates A and B with aldehydes, we hypothesized the possibility of performing selective vinylogous MBH or Wittig reactions of the intermediates A1 or B1 with aldehydes, depending on the electronic nature of the phosphines used. Herein, we report two such transformations: tandem vinylogous aldol/phosphorus-to-carbon aryl migration and vinylogous Wittig olefination.13

Scheme 3.

Transformations of enolate and ylide intermediates in phosphine-catalyzed reactions.

2. Results and discussion

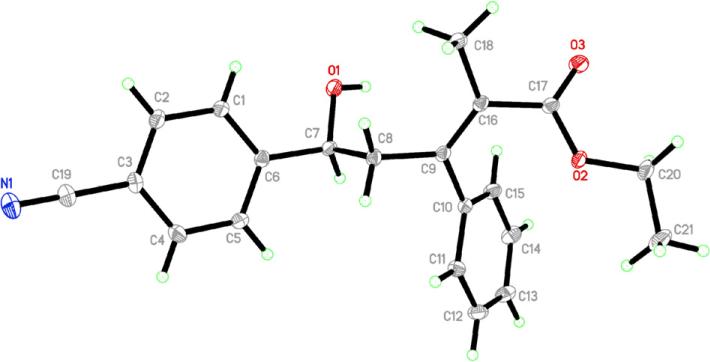

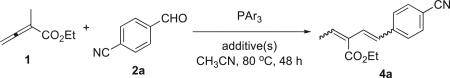

Table 1 lists the results of our preliminary study into the reactions between α-methyl allenic ester and aromatic aldehydes. We initially examined the reaction of benzaldehyde in benzene under reflux.14 Using alkylphosphines (PMe3, PBu3, PBn3, and PCy3) or HMPT in the reaction resulted in only oligomerization of the allenic ester without incorporation of benzaldehyde; in contrast, triphenylphosphine facilitated the anticipated MBH-type reaction.15 The reactions performed in benzene, toluene, or ethyl acetate under reflux provided the same yield of product 3a (entries 1–3). In the absence of solvent, the reaction was complete within 2 h with a slightly diminished yield of product 3a (entry 4). As we have observed consistently for the reactions between allenoates and aldehydes,16 the enolate A1 reacted with the aldehyde preferably at its γ carbon atom. In addition, for this reaction we observed a rare 1,2-aryl migration from the aryl phosphonium moiety to the neighboring α carbon atom.17 We established the structures of the aldol-type products 3 using 1H NMR, 13C NMR, and 2D-NMR spectroscopy and X-ray crystallographic analysis (Fig. 1, 3c).18

Table 1.

Preliminary study of the reactions between allenoate 1 and aldehydes 2a

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Ar | R | Solvent | Time [h] | Temp [°C] | Yieldb [%] |

| 1 | C6H5 | C6H5 | Benzene | 24 | Reflux | 28 (3a) |

| 2 | C6H5 | C6H5 | Toluene | 24 | Reflux | 28 (3a) |

| 3 | C6H5 | C6H5 | EtOAc | 24 | Reflux | 28 (3a) |

| 4c | C6H5 | C6H5 | Neat | 2 | 160 | 25 (3a) |

| 5 | 4-CF3C6H4 | C6H5 | Benzene | 24 | Reflux | 33 (3b) |

| 6 | 4-NCC6H4 | C6H5 | Toluene | 24 | Reflux | 33 (3c) |

| 7 | 4-NCC6H4 | C6H5 | Toluene | 24 | rt | Trace (3c) |

| 8 | 4-NCC6H4 | C6H5 | MeOH | 24 | rt | 0 |

| 9 | 4-BrC6H4 | C6H5 | Benzene | 24 | Reflux | 21 (3d) |

| 10 | 3-HOC6H4 | C6H5 | Benzene | 24 | Reflux | 0 |

| 11c,d | 4-Me2NC6H4 | C6H5 | Toluene | 54 | 160 | 0 |

| 12c | 4-Me2NC6H4 | C6H5 | Neat | 48 | 160 | 0 |

| 13 | 4-NCC6H4 | 4-MeC6H4 | Toluene | 24 | Reflux | 21 (3e) |

| 14e | 4-NCC6H4 | C6H5 | Toluene | 24 | Reflux | 37 (4a) |

Allenic ester (1.2 mmol) in solvent (10 mL) was added slowly (over 2 h) via a syringe pump into the mixture of the other reaction components (1.0 mmol of aldehyde and 1.0 mmol of phosphine) in solvent (5 mL).

Isolated yield of product.

Reaction was performed in a sealed tube.

Total volume of solvent: 2 mL.

BF3·Et2O (10 mol %) was added to the reaction mixture.

Figure 1.

ORTEP representation of compound 3c.

The presence of an electron-withdrawing substituent in the aromatic aldehyde slightly increased the yields of products 3b and 3c (entries 5 and 6). When performed in toluene at room temperature, however, the reaction afforded only a trace amount of product 3c (entry 7). We suspect that high temperature was required to facilitate the 1,2-aryl migration, but it also accelerated the phosphine-catalyzed oligomerization of the allenic ester, thereby resulting in moderate overall reaction efficiency. At room temperature in methanol, we did not detect the formation of product 3c (entry 8). Although p-bromobenzaldehyde provided moderate reaction efficiency (product 3d, entry 9), hydroxy- and amino-substituted benzaldehydes did not yield any aldol-like products under any of the tested conditions (entries 10–12). Using tris(p-tolyl)phosphine under the working conditions afforded product 3e, verifying that triphenylphosphine was the source of the phenyl group in products 3a–d (entry 13). Tris(p-tolyl)phosphine afforded a lower yield of 3e than did triphenylphosphine, presumably because a phosphine of stronger nucleophilicity led to increased oligomerization of the allenic ester and/or because of the poorer migratory aptitude of the electron-rich p-tolyl group (see Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

Suggested mechanisms for the vinylogous Wittig and vinylogous aldol/aryl migration reactions.

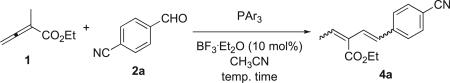

Aromatic aldehydes might not have been active enough for the nucleophilic addition of the dienolate and, therefore, such reactions were susceptible to competition from the oligomerization of the allenic ester. Lewis acids are commonly used to activate carbonyl compounds toward nucleophilic addition.19 Therefore, we added a catalytic amount (0.1 equiv) of boron trifluoride etherate in an attempt to enhance the efficiency of the desired reactions between the dienolate and the aromatic aldehydes. Surprisingly, the formation of product 3a was inhibited while the yield of the Wittig-type product 4a increased significantly (entry 14). Notably, the Lewis basic phosphine and Lewis acidic boron trifluoride etherate were compatible in this instance. We postulate three possible functions for the catalytic Lewis acid in the formation of 4a: (1) enhancing the electrophilicity of the carbonyl group of the aromatic aldehyde, (2) suppressing enolate formation from enolizable carbonyl compounds, much like CeCl3,20 and (3) facilitating the addition at the β′ carbon atom via simultaneous coordination to the carbonyl groups of both the aldehyde and the allenic ester (Scheme 4; vide infra).

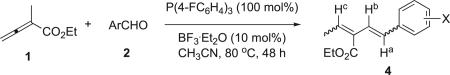

Among the series of organic solvents tested,21 acetonitrile was most efficacious for the Wittig reaction (Table 2). We obtained the diene 4a as a mixture of four possible isomers, as was the case also in Corey's diene synthesis via a vinylogous Wittig reaction.13 In an attempt to reduce the yield of the minor isomers of product 4a, we ran the reaction at 0 °C, but did not detect any product 4a (Table 2, entry 1). The Wittig reaction was sensitive to the temperature, providing a greater yield of product 4a at elevated temperatures (Table 2, entries 1–5). Increasing the amount of allenic ester in the reaction mixture did not improve the reaction efficiency; it only increased the degree of oligomerization of the allenic ester (Table 2, entries 2 and 3). Elevating the reaction temperature resulted in an increase in the reaction rate and the reaction yield of 4a (Table 2, entries 4 and 5). Surprisingly, the use of 5.0 equiv of the aldehyde lowered the reaction yield of product 4a (Table 2, entry 6), presumably because the relatively small amount (0.1 equiv) of BF3·Et2O was no longer effective to activate a large excess of aldehyde in the reaction mixture. The addition of more triphenylphosphine, on the other hand, increased the product yield significantly (Table 2, entry 7). In a previous study, we found that tris(4-fluorophenyl)phosphine preferentially facilitated reactions via the vinylogous ylide B1.11 Indeed, the use of tris(4-fluorophenyl)phosphine increased the yield of the reaction from 30% (Table 2, entry 2) to 47% (Table 2, entry 8) under otherwise identical reaction conditions. Nevertheless, because tris(4-fluorophenyl)phosphine is a weaker nucleophile, the reaction took longer to complete at room temperature.

Table 2.

Vinylogous Wittig reactions between the allenoate 1 and the aldehyde 2aa

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | 1 (equiv) | 2a (equiv) | PAr3 (equiv) | t [h] | T [°C] | Yieldb [%] |

| 1 | 1.2 | 1 | PPh3 (1) | 36 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 1.2 | 1 | PPh3 (1) | 36 | rtc | 30 |

| 3 | 2.5 | 1 | PPh3 (1) | 36 | rt | 30 |

| 4 | 1.2 | 1 | PPh3 (1) | 36 | 40 | 37 |

| 5 | 1.2 | 1 | PPh3 (1) | 30 | 80 | 42 |

| 6 | 1.2 | 5 | PPh3 (1) | 30 | 80 | 29 |

| 7 | 1.2 | 1 | PPh3 (5) | 30 | 80 | 55 |

| 8 | 1.2 | 1 | (4-FC6H4)3P (1) | 144 | rt | 47 |

Allenic ester in CH3CN (5 mL) was added in one portion to a mixture of the other components in CH3CN (10 mL).

Isolated yield.

rt=room temperature.

Next, we examined the effects of further modifications of the reaction conditions. At elevated temperature and using tris(4-fluorophenyl)phosphine, the desired transformation occurred within a reasonable amount of time with an increased yield of the isolated diene product (Table 3, entry 1). In the absence of the BF3·Et2O catalyst, however, even the use of tris(4-fluorophenyl)phosphine did not afford a good yield of the reaction product (entry 2). Increasing the loading of BF3·Et2O (from 10 to 20 mol %) lowered the reaction yield (entry 3), whereas a slight increase in the loadings of both the phosphine and BF3·Et2O resulted in a slight increase in the reaction yield of product 4a (entry 4). The reaction could not tolerate a stoichiometric amount of BF3·Et2O (entry 5), even in the presence of an increased amount of phosphine (entry 6). Although trace amounts of water or alcohol can be useful for catalyzing stepwise proton transfers in some phosphine-mediated reactions,22 we found that an excess of a protic solvent lowered the reaction yield of 4a in this reaction system (entry 7). When we used TiCl4 as the Lewis acid additive, rather than BF3·Et2O, the yield of product 4a remained unchanged (cf. entries 1 and 8).23 The introduction of TBAF as an additive did not improve the reaction yield (entry 9).

Table 3.

Effects of various phosphines and additives on the vinylogous Wittig reaction

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Ar | PAr3 (equiv) | Additive | Additive (mol %) | Yielda [%] |

| 1 | 4-FC6H4 | 1 | BF3·Et2O | 10 | 63 |

| 2 | 4-FC6H4 | 1 | None | N/A | 30 |

| 3 | 4-FC6H4 | 1 | BF3·Et2O | 20 | 56 |

| 4 | 4-FC6H4 | 1.3 | BF3·Et2O | 30 | 66 |

| 5 | Ph | 1 | BF3·Et2O | 100 | 0 |

| 6 | Ph | 2 | BF3·Et2O | 100 | 0 |

| 7b | 4-FC6H4 | 1 | BF3·Et2O | 10 | 52 |

| 8 | 4-FC6H4 | 1 | TiCl4 | 10 | 62 |

| 9 | Ph | 1 | TBAF | 10 | 28 |

Isolated yield.

MeOH (two drops) was added.

Next, we examined the effects that electron-withdrawing substituents at various positions on the aromatic ring of the benzaldehydes had on the vinylogous Wittig reactions (Table 4). Cyano groups (entries 1–3), in general, afforded greater yields of the diene 4 than did nitro substituents (entries 4–6). These electron-withdrawing groups were most effective at the meta positions of the aromatic aldehydes (entries 2 and 5). Introducing the substituent at the ortho position lowered the reaction yields of the dienes 4 (entries 3 and 6), presumably because steric hindrance negatively affected the nucleophilic addition step during the vinylogous Wittig reaction. Installing a weaker electron-withdrawing group (fluorine atom) on the aromatic ring lowered the reaction yield (entry 7). The presence of the various electron-withdrawing groups slightly affected the E/Z ratios of the newly formed bonds in the product mixtures (see below for the discussion); in all cases, the E-configuration of the new double bond was favored over the Z-configuration (from 2:1 to 5:1, Table 4).

Table 4.

Effects of various aldehyde substrates on the vinylogous Wittig transformationa

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | Ar | Product | Yieldb [%] | E/Z ratioc |

| 1 | 4-NCC6H4 | 4a | 63 | 5:2 |

| 2 | 3-NCC6H4 | 4b | 65 | 5:2 |

| 3 | 2-NCC6H4 | 4c | 60 | 5:1 |

| 4 | 4-O2NC6H4 | 4d | 51 | 4:1 |

| 5 | 3-O2NC6H4 | 4e | 57 | 2:1 |

| 6 | 2-O2NC6H4 | 4f | 50 | 7:2 |

| 7 | 3-FC6H4 | 4g | 49 | 5:2 |

Allenic ester in CH3CN (5 mL) was added in one portion to the mixture of the other components in CH3CN (10 mL).

Isolated yield.

Relating to the geometry around the newly formed double bond; the ratio was determined after integration of the signals of protons Ha and Hb in the 1H NMR spectrum of the crude reaction product.

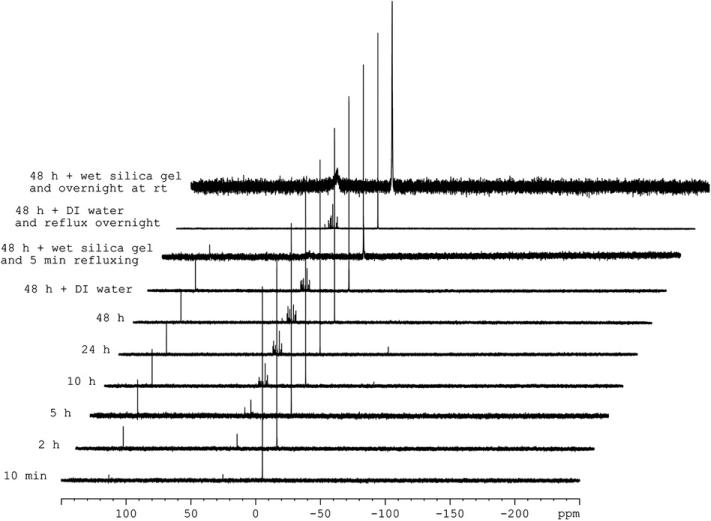

Scheme 4 presents a suggested mechanism for the formation of 3 and 4. The phosphine first underwent a Michael addition to the allenic ester 1 to form the enolate zwitterion 5. Subsequent stepwise proton transfers established the equilibrium between the dienolate 5 and the vinylogous ylide 6.11 Dependent upon the nature of the phosphine in use, as well as the presence/absence of a Lewis acid, either the dienolate or the vinylogous ylide became the dominant species for reaction with the aldehyde. For the vinylogous aldol/1,2-aryl migration pathway, the dienolate 5 added to the aldehyde 2 to form the alkoxide 7. Stepwise proton transfers then occurred to form the ylide 8,24 which underwent a net 1,2-aryl migration, through an intramolecular SNAr reaction, to generate the phosphine 9. The oxophilicity of the alkyldiphenylphosphine 9 accounts for the formation of the phosphinite 10, which eventually hydrolyzed during purification to form the alcohol 3. 31P NMR spectra of the reaction mixture in C6D6 heated under reflux for 10 min, 2 h, 5 h, 10 h, and 24 h revealed a peak at δ 113.3 ppm of increasing intensity (Fig. 2), indicative of the accumulation of the phosphinite 10.25 This peak did not disappear upon addition of water; it did, however, slowly decrease in intensity upon the addition of wet silica gel, completely disappearing after treatment overnight at room temperature. For the vinylogous Wittig pathway, the vinylogous ylide added to the Lewis acid-activated aldehyde 2 to form the phosphonium alkoxide 11. A series of proton transfer processes would establish an equilibrium between the alkoxide 11 and the vinylogous ylide 12. Additional stepwise proton transfers (or, potentially, a one-step intramolecular 1,5-proton transfer) converted the vinylogous ylide 12 to the allylic phosphonium 13, which cyclized to form a six-membered-ring product, the 3,6-dihydro-2,2,2-triphenyl-1,2-oxaphosphonine 14. Through a retro-Diels–Alder (rDA) process, triphenylphosphine oxide was formed from 14, resulting in the diene 4 being obtained as a mixture of isomers.13

Figure 2.

31P NMR spectra of a reaction mixture of the allenoate 1, 4-cyanobenzaldehyde, and PPh3 in C6D6 heated under reflux, revealing the accumulation of the alkyl diphenylphosphinite intermediate 10.

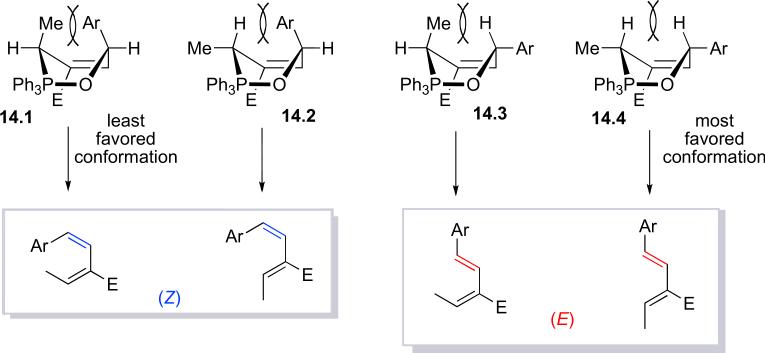

Unlike regular Wittig reactions, which favor formation of Z-olefins, the configurations of our newly formed olefins from these vinylogous Wittig reactions were determined by their steric surroundings. The proposed 3,6-dihydro-2,2,2-triphenyl-1,2-oxaphosphonine intermediate 14 is assembled into a boat conformation so that the π and σ* orbitals are aligned properly for the rDA process.26 Scheme 5 presents four possible relative arrangements for the substituents at C3 and C6. We would expect the intermediate 14.4 to form most favorably because of its limited degree of steric congestion; accordingly, intermediate 14.1 would be the least likely to form. Even though an aryl group is larger than a methyl group, its flat and rigid ring can orient itself to minimize van der Waals repulsion with other groups.27 We would also expect the intermediate 14.2 to be more favorable than 14.3; indeed, the corresponding Z-olefin generated from 14.2 was the second-most-abundant product, as determined through 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis. The pseudoaxial aryl group in the boat conformation of 14.2 is oriented in such a manner to minimize van der Waals repulsion of the pseudoaxial allylic hydrogen atom. The methyl group, in contrast, with its tetrahedral configuration, suffers severe van der Waals repulsion with the proximal pseudoaxial allylic proton in the boat conformation 14.3. The significant degree of Z-olefin formation presumably arose because the flat structure of the aromatic ring could minimize the extent of flagpole interactions with the hydrogen atom in structure 14.2.

Scheme 5.

Retro-Diels–Alder reactions of four conformations of the 3,6-dihydro-2,2,2-triphenyl-1,2-oxaphosphonine intermediate 14.

3. Conclusion

We have observed a classic case of equilibrium between phosphonium dienolates and vinylogous phosphorus ylides during the phosphine-mediated reactions of ethyl α-methylallenoate with various aldehydes. When we exposed the α-methyl allenic ester to the aldehydes in the presence of a tertiary phosphine, both aldol-type and Wittig reactions ensued. Specifically, triphenylphosphine facilitated a tandem vinylogous aldol/1,2-aryl phosphorus-to-carbon migration reaction between the α-methyl allenic ester and electron-deficient aromatic aldehydes. In the presence of substoichiometric amounts of a Lewis acid, such as BF3·Et2O or TiCl4, rare vinylogous Wittig olefinations occurred between the α-methyl allenic ester and electron-deficient aromatic aldehydes. The vinylogous Wittig reaction was best facilitated in the presence of the electron-deficient tris(p-fluorophenyl)phosphine. Products featuring thermodynamically more stable E-configurations were formed preferentially in the vinylogous Wittig reaction, in contrast to the Z-olefin formation traditionally observed for normal Wittig olefinations.

4. Experimental

4.1. General

All reactions were performed under argon atmosphere with dry solvents and anhydrous conditions, unless otherwise indicated. Benzene, toluene, acetonitrile, and BF3·Et2O were freshly distilled from CaH2 prior to use. All other reagents were used as received from commercial sources. Ethyl 2-methyl-2,3-butadienoate (1) was synthesized according to procedures reported previously.28 Reactions were monitored using thin layer chromatography (TLC), performed on 0.25-mm SiliCycle silica gel plates and visualized under UV light and with permanganate staining. Flash column chromatography (FCC) was performed using SiliCycle Silica-P Flash silica gel (60 Å pore size, 40–63 μm). IR spectra were recorded on a Perkin–Elmer paragon 1600 FT-IR spectrometer. NMR spectra were obtained on Bruker Avance-500 instruments, calibrated using residual undeuterated chloroform as an internal reference (7.26 and 77.0 ppm for 1H and 13C NMR spectra, respectively) and phosphoric acid as an external reference (0.00 ppm for 31P NMR spectra). 1H NMR spectral data are reported as follows: chemical shift (δ, ppm), multiplicity, coupling constant (Hz), and integration. 13C NMR spectral data are reported in terms of the chemical shift. Data for 31P NMR spectra are reported in terms of chemical shift. The following abbreviations are used to indicate multiplicities: s=singlet; d=doublet; t=triplet; q quartet; m=multiplet. MALDI mass spectrometric data were obtained using an Applied Biosystems Voyager-DE-STR MALDI-TOF instrument, samples dissolved in CH2Cl2, and 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid as the matrix. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC–MS) data were obtained using an Agilent 6890–5975 GC–MS system equipped with an autosampler and an HP5 column; samples were dissolved in CH2Cl2.

4.2. General procedure for preparation of 3

A flame-dried round-bottom flask was charged with triphenylphosphine (1.0 mmol), an aldehyde (1.0 mmol), and dry toluene (5 mL). The mixture was heated under reflux and then ethyl 2-methyl-2,3-butadienoate (1.2 mmol) was added slowly via a syringe pump over 2 h. The mixture was then heated under reflux for 24 h before being concentrated. The crude residue was purified through FCC (SiO2; hexanes/ethyl acetate, 8:3) to afford the alcohol 3.

4.2.1. (Z)-Ethyl 5-Hydroxy-2-methyl-3,5-diphenyl-2-pentenoate (3a)

Yield 27%; pale yellow oil. IR (film) νmax 3460, 3059, 3028, 2980, 2927, 1705, 1311, 1244, 1140 cm–1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.29–7.11 (m, 10H), 4.58 (ddd, J=1.8, 5.1, 5.8 Hz, 1H), 3.81 (q, J=7.5 Hz, 2H), 3.04 (dd, J=8.5, 14.0 Hz, 1H), 2.80 (dd, J=5.0, 14.0 Hz, 1H), 1.95 (s, 3H), 0.80 (t, J=7.5 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 170.6, 143.7, 142.1, 142.0, 129.6, 128.3, 128.1, 127.61, 127.58, 127.1, 125.6, 72.2, 60.2, 44.5, 16.2, 13.4; MS (MALDI) calcd for C20H22NaO3 [M+Na]+ 333.15, found 333.14.

4.2.2. (Z)-Ethyl 5-(p-trifluoromethylphenyl)-5-hydroxy-3-phenyl-2-methyl-2-pentenoate (3b)

Yield 33%; pale yellow oil. IR (film) νmax 3460, 3057, 2983, 2929, 1706, 1326, 1164, 1125, 1067 cm–1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.47 (d, J=8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.31 (d, J=8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.25–7.18 (m, 3H), 7.09–7.07 (m, 2H), 4.56–4.57 (m, 1H), 3.74 (q, J=7.0 Hz, 2H), 2.94 (dd, J=9.0, 14 Hz, 1H), 2.69 (dd, J=5.0, 13.5 Hz, 1H), 1.89 (s, 3H), 0.72 (t, J=7.0 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 170.5, 147.6, 141.6, 141.3, 130.0, 129.7 (q, J=32.3 Hz), 128.2, 127.5, 127.3, 125.9, 125.2 (q, J=3.7 Hz), 124.0 (q, J=272.3 Hz), 71.5, 60.3, 44.4, 16.2, 13.3; MS (MALDI) calcd for C21H21F3NaO3 [M+Na]+ 401.13, found 401.22.

4.2.3. (Z)-Ethyl 5-(p-cyanophenyl)-5-hydroxy-2-methyl-3-phenyl-2-pentenoate (3c)

Yield 33%; colorless oil. IR (film) νmax 3474, 3051, 2978, 2925, 2229, 1705, 1311, 1245, 1140, 1067 cm–1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.50 (d, J=8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.31 (d, J=8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.25–7.19 (m, 3H), 7.08 (d, J=6.5 Hz, 2H), 4.56–4.54 (m, 1H), 3.74 (q, J=7.0 Hz, 2H), 2.92 (dd, J=14.0, 8.5 Hz, 1H), 2.68 (dd, J=14.0, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 2.51 (s, 1H), 1.84 (s, 3H), 0.72 (t, J=7.0 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 170.5, 149.1, 141.5, 141.0, 132.1, 130.1, 128.2, 127.5, 127.4, 126.3, 118.7, 111.1, 71.4, 60.3, 44.3, 16.3, 13.3; MS (MALDI) calcd for C21H21NO3Na [M+Na]+ 358.14, found 358.12.

4.2.4. (Z)-Ethyl 5-(p-bromophenyl)-5-hydroxy-3-phenyl-2-methyl-2-pentenoate (3d)

Yield 21%; colorless oil. IR (film) νmax 3468, 3050, 3018, 2981, 2927, 1707, 1311, 1242, 1141 cm–1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.38 (d, J=6.5 Hz, 2H), 7.28–7.25 (m, 3H), 7.12–7.09 (m, 4H), 4.47 (dd, J=5.0, 8.0 Hz, 1H), 3.77 (q, J=7.0 Hz, 2H), 2.96 (dd, J=8.5, 13.5 Hz, 1H), 2.73 (s, 1H), 2.71 (dd, J=5.5, 14.5 Hz, 1H), 1.89 (s, 3H), 0.77 (t, J=7.0 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 170.7, 142.8, 141.8, 141.7, 131.3, 129.6, 128.1, 127.6, 127.4, 127.2, 121.2, 71.4, 60.3, 44.3, 16.2, 13.3.

4.2.5. (Z)-Ethyl 5-(p-cyanophenyl)-5-hydroxy-2-methyl-3-(p-tolyl)-2-pentenoate (3e)

Yield 21%; pale yellow oil. IR (film) νmax 3472, 3055, 2980, 2302, 1706, 1312, 1245, 1141, 1067 cm–1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.60 (d, J=8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.50 (d, J=7.5 Hz, 2H), 7.13 (d, J=8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.06 (d, J=8.5 Hz, 2H), 4.64 (dd, J=4.0, 8.5 Hz, 1H), 3.86 (q, J=7.0 Hz, 2H), 2.97 (dd, J=8.5, 14.0 Hz, 1H), 2.75 (dd, J=4.0, 14.0 Hz, 1H), 2.35 (s, 3H), 1.94 (s, 3H), 0.86 (t, J=7.0 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 170.5, 149.0, 140.8, 138.3, 137.3, 132.1, 130.0, 129.0, 127.4, 126.3, 118.7, 111.2, 71.5, 60.3, 43.3, 21.1, 16.3, 13.4.

4.3. General procedure for preparation of 4

A flame-dried round-bottom flask was charged with tris(4-fluorophenyl)phosphine (1.0 mmol), an aldehyde (1.0 mmol), and dry acetonitrile (10 mL). The mixture was stirred and heated to 80 °C in an oil bath and then a solution of ethyl 2-methyl-2,3-butadienoate in dry acetonitrile (5 mL) was added to the mixture in one portion. After the reaction had reached completion (ca. 48 h), the mixture was concentrated and the crude residue purified through FCC (SiO2; hexanes/ethyl acetate, 5:1) to provide a mixture of isomeric dienes. The number of isomers in the mixture was determined by GC–MS; the ratio of isomers was calculated from 1H NMR spectral data of the crude product.

4.3.1. Ethyl 2-(4-cyanostyryl)-2-butenoate (4a)

Yield 63%; colorless oil. IR (film) νmax 3047, 2982, 2938, 2226, 1713, 1603, 1054, 1249, 1141 cm–1; (major isomer) 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.60 (d, J=8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.52 (d, J=8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.10 (d, J=16.4 Hz, 1H), 7.00 (d, J=16.4 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (q, J=7.2 Hz, 1H), 4.26 (q, J=7.2 2H), 2.02 (d, J=7.4 Hz, 3H), 1.33 (t, J=7.2 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.5, 142.0, 140.2, 132.3, 131.4, 130.4, 126.8, 124.0, 118.9, 110.7, 60.7, 14.7, 14.1; (second-most-abundant isomer) 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.50 (d, J=8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.34 (d, J=8.3 Hz, 2H), 6.88 (q, J=7.0 Hz, 1H), 6.63 (d, J=11.8 Hz, 1H), 6.36 (d, J=12.2 Hz, 1H), 4.08 (q, J=7.3 Hz, 2H), 1.59 (d, J=7.3 Hz, 3H), 1.16 (t, J=6.99 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.5, 142.1, 140.6, 132.0, 131.1, 130.1, 128.7, 126.3, 118.7, 110.5, 30.8, 15.3, 14.0; MS (Agilent GC–MS) calcd for C15H15NO2 [M+] 241.11, found 241.1.

4.3.2. Ethyl 2-(3-cyanostyryl)-2-butenoate (4b)

Yield 65%; colorless oil. IR (film) νmax 3063, 2982, 2916, 2849, 2230, 1714, 1576, 1477, 1256, 1139 cm–1; (major isomer) 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3; non-aromatic protons) δ 7.07 (d, J=16.5 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (d, J=16.5 Hz, 1H), 6.95 (q, J=7.5 Hz, 1H), 4.27 (q, J=7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.03 (d, J=7.4 Hz, 3H), 1.34 (t, J=7.2 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.6, 140.8, 139.8, 138.8, 132.8, 130.9, 130.7, 130.6, 129.7, 129.3, 118.7, 112.8, 60.7, 14.7, 14.2; (second-most-abundant isomer) 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3; non-aromatic protons) δ 6.77 (d, J=16.5 Hz, 1H), 6.59 (d, J=16.5 Hz, 1H), 6.22 (q, J=7.3 Hz, 1H), 4.36 (q, J=7.1 Hz, 2H), 1.99 (d, J=7.3 Hz, 3H), 1.39 (t, J=7.1 Hz, 3H); (third-most-abundant isomer) 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3; non-aromatic protons) δ 6.42 (d, J=12.0 Hz, 1H), 6.34 (dt, J=12.0, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 6.17 (qd, J=7.3, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 3.87 (q, J=7.2 Hz, 2H), 1.96 (dd, J=7.3, 1.2 Hz, 3H), 1.12 (t, J=7.2 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.5, 139.8, 138.5, 136.3, 131.9, 130.35, 140.31, 130.26, 128.8, 127.6, 118.7, 112.2, 60.4, 15.5, 13.8; MS (Agilent GC–MS) calcd for C15H15NO2 [M+] 241.11, found 241.1.

4.3.3. Ethyl 2-(2-cyanostyryl)-2-butenoate (4c)

Yield 60%; colorless oil. IR (film) νmax 3066, 2982, 2873, 2851, 2223, 1714, 1633, 1595, 1478, 1447, 1385, 1244, 1141, 1025 cm–1; (major isomer) 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3; non-aromatic protons) δ 7.36 (d, J=16.6 Hz, 1H), 7.10 (d, J=16.6 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (q, J=7.5 Hz, 1H), 4.29 (q, J=7.3 Hz, 2H), 2.06 (d, J=7.5 Hz, 3H), 1.36 (t, J=7.2 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.6, 140.8 (two peaks), 133.0, 132.7, 131.9, 130.5, 129.1, 127.6, 125.5, 117.8, 111.2, 60.9, 15.0, 14.1; (second-most-abundant isomer) 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3; non-aromatic protons) δ 7.00 (d, J=16.2 Hz, 1H), 6.92 (d, J=16.2 Hz, 1H), 6.33 (q, J=7.4 Hz, 1H), 4.37 (q, J=7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.03 (d, J=7.4 Hz, 3H), 1.41 (t, J=7.1 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.3, 141.6, 141.0, 132.5, 132.1, 131.2, 130.6, 129.5, 127.4, 125.8, 117.8, 111.9, 60.3, 15.5, 13.7; MS (Agilent GC–MS) calcd for C15H15NO2 [M+] 241.11, found 241.1.

4.3.4. Ethyl 2-(4-nitrostyryl)-2-butenoate (4d)

Yield 51%; yellow oil. IR (film) νmax 2984, 2916, 2848, 1714, 1593, 1513, 1343, 1256, 1143 cm–1; (major) 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.20 (d, J=8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.58 (d, J=8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.19 (d, J=16.5 Hz, 1H), 7.07 (d, J=16.5 Hz, 1H), 7.00 (q, J=7.5 Hz, 1H), 4.28 (q, J=7.0 Hz, 2H), 2.05 (d, J=7.5 Hz, 3H), 1.35 (t, J=7.0 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.7, 144.1, 140.9, 131.1, 130.5, 127.0, 125.0, 124.1, 123.6, 60.9, 14.9, 14.3; MS (Agilent GC–MS) calcd for C14H15NO4 [M+] 261.10, found 261.1.

4.3.5. Ethyl 2-(3-nitrostyryl)-2-butenoate (4e)

Yield 57%; yellow oil. IR (film) νmax 3089, 2980, 2916, 2849, 1712, 1529, 1530, 1253 cm–1; (major) 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.31 (s, 1H), 8.10 (dd, J=8.1, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.74 (d, J=7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (t, J=7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (d, J=16.5 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (d, J=16.5 Hz, 1H), 6.98 (q, J=7.4 Hz, 1H), 4.28 (q, J=7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.05 (d, J=7.4 Hz, 3H), 1.35 (t, J=7.1 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.8, 148.9, 140.2, 139.5, 132.4, 130.9, 130.4, 129.4, 123.5, 122.1, 120.8, 60.8, 14.8, 14.2; (second-most-abundant isomer) 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.12 (s, 1H), 8.06 (d, J=8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.58 (d, J=7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.45 (t, J=7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.49 (d, J=12.0 Hz, 1H), 6.38 (d, J=12.0 Hz, 1H), 6.20 (d, J=7.2 Hz, 1H), 3.87 (q, J=7.2 Hz, 2H), 1.97 (d, J=7.2 Hz, 3H), 1.11 (t, J=7.2 Hz, 3H); MS (Agilent GC–MS) calcd for C14H15NO4 [M+] 261.10, found 261.1.

4.3.6. Ethyl 2-(2-nitrostyryl)-2-butenoate (4f)

Yield 50% ; yellow oil. IR (film) νmax 3067, 2982, 2937, 2849, 1716, 1606, 1570, 1521, 1346, 1250, 1146, 1027 cm–1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.00 (d, J=8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (d, J=8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.64 (t, J=7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (d, J=16.3 Hz, 1H), 7.47–7.45 (m, 1H), 7.07 (q, J=7.4 Hz, 1H), 6.92 (d, J=16.3 Hz, 1H), 4.32 (q, J=7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.10 (d, J=7.4 Hz, 3H), 1.40 (t, J=7.1 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.6, 140.4, 133.3, 133.0, 132.9, 130.6, 128.7, 128.2, 128.0, 125.8, 124.5, 60.8, 14.9, 14.1; methyl and ethoxy protons of other minor isomers: (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 3.76 (q, J=7.1 Hz, 2H), 1.92 (d, J=7.5 Hz, 3H), 1.11 (t, J=7.1 Hz, 3H); δ 4.40 (q, J=7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.07 (d, J=7.5 Hz, 3H), 1.44 (t, J=7.1 Hz, 3H); δ 4.11 (q, J=7.1 Hz, 2H), 1.60 (dd, J=1.4, 7.4 Hz, 3H), 1.23 (t, J=7.1 Hz, 3H); MS (Agilent GC–MS) calcd for C14H15NO4 [M+] 261.10, found 261.1.

4.3.7. Ethyl 2-(3-fluorostyryl)-2-butenoate (4g)

Yield 49%; colorless oil. IR (film) νmax 3037, 2981, 2928, 2855, 1711, 1609, 1581, 1486, 1446, 1263, 1240, 1143 cm–1; (major) 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.30–7.26 (m, 1H), 7.21 (d, J=7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.18–7.14 (m, 1H), 7.03 (d, J=16.4 Hz, 1H), 6.97–6.93 (m, 1H), 6.902 (d, J=16.4 Hz, 1H), 6.903 (q, J=7.5 Hz, 1H), 4.27 (q, J=7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.01 (d, J=7.5 Hz, 3H), 1.34 (t, J=7.2 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.0, 163.1 (d, J=239.3 Hz), 139.9 (d, J=8.0 Hz), 138.8, 132.1 (d, J=3.2 Hz), 130.7, 129.9 (d, J=8.5 Hz), 122.4 (d, J=3.1 Hz), 121.9, 114.4 (d, J=21.6 Hz), 112.6 (d, J=21.8 Hz), 60.6, 14.7, 14.2; MS (Agilent GC–MS) calcd for C14H15O2F [M+] 234.11, found 234.1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Financial support was provided by the NIH (R01GM071779 and P41GM081282). We thank Dr. Saeed Khan (Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, UCLA) for performing the crystallographic analysis.

Footnotes

Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.tet.2010.03.044.

References and notes

- 1.Horner VL, Jurgeleit W, Klupfel K. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1955;591:108. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takashina N, Price CC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1962;84:489. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rauhut MM, Currier H. 1963 U.S. Patent 307,499,919,630,122.

- 4.Oda R, Kawabata T, Tanimoto S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1964;5:1653. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morita K, Suzuki Z, Hirose H. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1968;41:2815. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baylis AB, Hillman MED. 1972 German Patent 2155113.

- 7.Baizer MM, Anderson JD. J. Org. Chem. 1965;30:1357. [Google Scholar]

- 8.For recent reviews on the MBH reaction, see: Declerck V, Martinez J, Lamaty F. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:1. doi: 10.1021/cr068057c.; Aroyan CE, Dermenci A, Miller SJ. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:4069.; Singh V, Batra S. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:4511.; Basavaiah D, Rao KV, Reddy RJ. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:1581. doi: 10.1039/b613741p.; Shi Y-L, Shi M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007:2905.; Masson G, Housseman C, Zhu J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2007;46:4614. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604366.; Basavaiah D, Rao AJ, Satyanarayana T. Chem. Rev. 2003;103:811. doi: 10.1021/cr010043d.; Langer P. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000;39:3049. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20000901)39:17<3049::aid-anie3049>3.0.co;2-5.

- 9.For reviews on nucleophilic phosphine catalysis, other than MBH reactions, see: Lu X, Zhang C, Xu Z. Acc. Chem. Res. 2001;34:535. doi: 10.1021/ar000253x.; Valentine DH, Hillhouse JH. Synthesis. 2003;3:317.; Methot JL, Roush WR. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2004;346:1035.; Lu X, Du Y, Lu C. Pure Appl. Chem. 2005;77:1985.; Nair V, Menon RS, Sreekanth AR, Abhilash N, Biju AT. Acc. Chem. Res. 2006;39:520. doi: 10.1021/ar0502026.; Denmark SE, Beutner GL. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:1560. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604943.; Ye L-W, Zhou J, Tang Y. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008;37:1140. doi: 10.1039/b717758e.; Kwong CK-W, Fu MY, Lam CS-L, Toy PH. Synthesis. 2008:2307.; Cowen BJ, Miller SJ. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:3102. doi: 10.1039/b816700c.

- 10.After our reports on the reactions between α-alkyl allenoates and imines (Ref. 28) and olefins (Ref. 11), He's group published a series of papers on the reactions between α-alkyl allenoates and aldehydes; see: He Z, Tang X, He Z. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2008;183:1518.; Xu S, Zhou L, Ma R, Song H, He Z. Org. Lett. 2010;12:544. doi: 10.1021/ol902747c.; For examples of reactions between γ-alkyl allenoates and aldehydes, see: Xu S, Zhou L, Ma R, Song H, He Z. Chem.—Eur. J. 2009;15:8698. doi: 10.1002/chem.200901276.; Xu S, Zhou L, Zeng S, Ma R, Wang Z, He Z. Org. Lett. 2009;11:3498. doi: 10.1021/ol901334c.

- 11.Tran YS, Kwon O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12632. doi: 10.1021/ja0752181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a Farrar DH, Poe AJ, Zheng Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:6252. [Google Scholar]; b Denmark SE, Chung W. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:4002. doi: 10.1021/jo060153q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corey EJ, Erickson BW. J. Org. Chem. 1974;39:821. [Google Scholar]

- 14.The reactions performed at room temperature did not provide any identifiable products derived from the allenoate and benzaldehyde.

- 15.No alkyl migration occurred with these phosphines (only oligomerization of the allenoate): PMe3, PBu3, HMPT, PBn3, and PCy3.

- 16.a Zhu X, Henry CE, Wang J, Dudding T, Kwon O. Org. Lett. 2005;7:1387. doi: 10.1021/ol050203y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Zhu X, Schaffner A, Li RC, Kwon O. Org. Lett. 2005;7:2977. doi: 10.1021/ol050946j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Dudding T, Kwon O, Mercier E. Org. Lett. 2006;8:3643. doi: 10.1021/ol061095y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Creech GS, Kwon O. Org. Lett. 2008;10:429. doi: 10.1021/ol702462w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Creech GS, Zhu X, Fonovic B, Dudding T, Kwon O. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:6935. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2008.04.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.a Allen DW, Tebby JC. Tetrahedron. 1967;23:2795. [Google Scholar]; b Allen DW, Hutley BG. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1979:1499. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crystallographic data for 3c has been deposited with the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre as supplementary number CCDC 763343. The data can be obtained online free of charge [or from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center, 12, Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: +44 1223 336 033; or deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk].

- 19.a Ooi T, Maruoka K. In: Modern Carbonyl Chemistry. Otera J, editor. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2000. Chapter 1. [Google Scholar]; b Yamamoto H, Nakashima D. In: Acid Catalysis in Modern Organic Synthesis. Yamamoto H, Ishihara K, editors. Vol. 1. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2008. Chapter 1. [Google Scholar]

- 20.a Kolakowski RV, Manpadi M, Zhang Y, Emge TJ, Williams LJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:12910. doi: 10.1021/ja906189h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Imamoto T, Takiyama N, Nakamura K, Hatajima T, Kamiya Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:4392. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solvents tested: toluene, benzene, xylene, neat (no solvent), DCM, 1,2-dichloroethane (DCE), chloroform, acetone, diethyl ether, THF, dioxane, DMSO, methanol, isopropanol, tert-butanol, and acetonitrile.

- 22.Liang Y, Liu S, Xia Y, Li Y, Yu Z-X. Chem.—Eur. J. 2008;14:4361. doi: 10.1002/chem.200701725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Other additives tested that were not as efficient as BF3·Et2O: AgOAc, CeCl3, AlCl3, CsF, LiCl, KF, FeCl3, CrCl3, and ZnCl2.

- 24.Under the same conditions, the reaction of the parent allenic ester, ethyl 2,3-butadienoate, provided no aryl migration product.

- 25.Selected 31P NMR spectroscopic data of the alkyl diphenylphosphinite: δ 115.6 (Ph2OMe), 109.8 (Ph2POEt), 111.1 (Ph2POBu), 104 (Ph2POc-Hex), 117.0 (Ph2POCH2c-Hex), 113.4 (Ph2POCH2CH=CH2) ppm Platt AWG, Kleemann SG. 31P NMR data of three coordinate (λ3 σ3) phosphorus compounds containing bonds to chalcogenides (O, S, Se, Te) but no bonds to halogen. In: Tebby JC, editor. Handbook of Phosphorus-31 Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Data. CRC; Boca Raton, FL: 1991. p. 85.

- 26.a Pool BR, White JM. Org. Lett. 2000;2:3505. doi: 10.1021/ol006553w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Birney D, Lim TK, Koh JHP, Pool BR, White JM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:5091. doi: 10.1021/ja025634f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.a Eliel EL, Manoharan M. J. Org. Chem. 1981;46:1959. [Google Scholar]; b Allinger NL, Tribble MT. Tetrahedron Lett. 1971;35:3259. [Google Scholar]; c Wiberg KB, Castejon H, Bailey WF, Ochterski J. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:1181. doi: 10.1021/jo9917386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu X-F, Lan J, Kwon O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:4716. doi: 10.1021/ja0344009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.