Abstract

We present the case of an incarcerated Spigelian hernia that manifested 24 hours after a laparoscopic living-donor nephrectomy. The differential diagnosis, proposed management, and a review of the literature is presented.

Bowel obstruction occurring within a few days following laparoscopic surgery is most often attributed to a hernia at a trocar site.1, 2 In the case of living-donor nephrectomy, the hernia could also occur at the incision made for removal of the kidney. Spigelian hernia has not been reported as a complication of laparoscopic surgery in the past and, therefore, would not normally be considered in the differential diagnosis of any complications following laparoscopic surgery.

With the increasing use of laparoscopy, unsuspected intraabdominal conditions may be diagnosed during the procedure or become manifest because of increased intraabdominal pressure created by the pneumoperitoneum. Here we report the diagnosis and repair of a Spigelian hernia that became manifest 1 day after laparoscopic nephrectomy.

Keywords: Laparoscopic nephrectomy, Kidney transplant, Spigelian hernia

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic living-donor nephrectomy has gained worldwide acceptance since first being described in 1995. In experienced hands, the technique has been shown to be safe and to provide kidneys for transplantation that function identically to those of historic open nephrectomy controls.3 As with any laparoscopic procedure, a postoperative hernia is a potential complication. Typically, these hernias are located at trocar sites. We report a complication of laparoscopic living-donor nephrectomy in which incarceration of a Spigelian hernia occurred postoperatively.

CASE REPORT

BG is a 51-year-old woman who wished to donate a kidney to her sister. Her initial evaluation revealed normal renal function and excellent health with the exception of obesity. At our transplant program, we have set a limit of a body mass index of 40 for patients to be accepted as living kidney donors. The patient stated that she was already planning to undergo a gastric stapling procedure. She was told that such a procedure would not prevent her from being an organ donor.

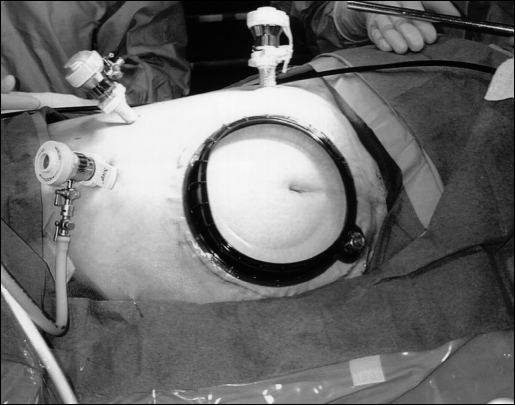

Eight months after her bariatric surgery, the patient had lost a significant amount of weight and had a body mass index of less than 40. Repeat history, physical examination, and laboratory testing did not reveal any contraindications to kidney donation. A spiral 3-dimensional CT scan was performed. Her renal anatomy was normal bilaterally. Adhesions to an upper midline incision were noted. However, no hernias or other abnormalities were identified. A left ureteral nephrectomy was performed with a laparoscopic hand-assisted technique.3 The patient was positioned in the right lateral decubitus position. Trocars and hand-assist port placement were sited in the usual manner (Figure 1). Adequate exposure required lysis of some adhesions resulting from the previous surgery, but these were not extensive. Inspection of the previous upper midline incision did not reveal any evidence of herniation. The donor nephrectomy was uneventful. Pneumoperitoneum was maintained between 14 and 16 mm Hg throughout. The total time of pneumoperitoneum was less than 2 hours. The kidney was removed through an 8-cm lower midline incision made early during the procedure for hand-assistance with the Pneumosleeve® device. The midline fascia was closed with a running suture at the end of the procedure.

Figure 1.

Trocar and hand-assist port placement.

The patient's initial postoperative course was unremarkable. She began a liquid diet the evening of surgery and required only oral narcotics for pain. On the morning of the first postoperative day, the patient stated that she felt ready to go home. However, 2 hours later, while walking in the hall, she noted a large “bulge” on the right side of her abdomen and mild to moderate abdominal pain and nausea. A physical examination revealed a 6 x 8-cm nonreducible mass to the right of the umbilicus. A CT scan was obtained that demonstrated herniation of the small bowel through a right-sided fascial defect lateral to the midline. Operative exploration through the midline incision made for hand-assisted laparoscopy revealed a fascial defect with herniation of the small bowel at the lateral border of the rectus muscle at the semilunar line of Douglas. The hernia defect was 4 to 5 cm lateral to the hand-assist midline incision. The abdominal wall tissue in this area was noted to be quite thin and weak. Herniorrhaphy was accomplished with a prosthetic patch technique.

DISCUSSION

This is the first known report of a previously undiagnosed Spigelian hernia becoming manifest 1 day after a laparoscopic procedure. We believe this Spigelian hernia occurred through a preexisting fascial weakness but that the herniation itself was the result of pneumoperitoneum. The patient had abdominal CT scanning 2 weeks prior to the laparoscopic nephrectomy, which did not reveal any evidence of an abdominal hernia. The hernia was not recognized during the laparoscopic nephrectomy. This is most likely due to the patient being in the right lateral decubitus position, because the bowel tends to settle against the lower abdominal wall making inspection of this area impossible.

Spigelian hernias are uncommon and are often a diagnostic challenge. The definition and characterization of Spigelian hernias has been published by Spagen.4 These hernias are relatively uncommon with fewer than 1,000 being reported in the literature. Spigelian hernias occur through the Spigelia fascia, which is the part of the trans-verses abdominus aponeurosis lying between the semilunar line and the lateral edge of the rectus muscle.

Spigelian hernias may contain preperitoneal fat, greater omentum, small intestine or colon, or rarely other organs.4 Approximately 20% of reported Spigelian hernias were incarcerated at the time of operation.4

Patients with Spigelian hernias may complain of pain, local swelling, or both. However, the symptoms, location, and severity are quite variable, and may be intermittent, making diagnosis difficult. In addition, many patients with Spigelian hernias have no finding on physical examination. The relatively large, palpable mass in our patient is unusual. In addition, bowel obstruction is not commonly reported.

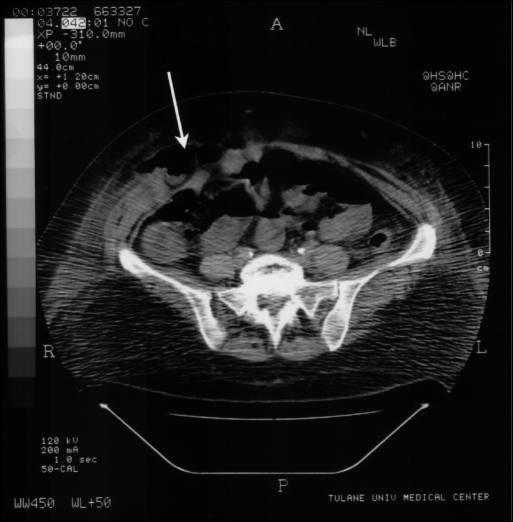

Trocar site hernias following laparoscopic surgery are well known and have been reported as causing bowel obstruction and potential strangulation.1, 5 In our patient, herniation through the lower midline incision used for the hand-assisted technique was initially felt to be the most likely site for a hernia causing the patient's symptoms so soon after surgery. However, due to the physical examination findings of a palpable nonreducible mass, lateral to the edge of the rectus muscle, the diagnosis of Spigelian hernia was considered and a CT scan was performed that confirmed this diagnosis (Figure 2). The diagnosis was further confirmed by intraoperative findings. The hernia defect was located 4 to 5 cm lateral to the midline incision. No evidence existed that the 7-cm midline incision made for hand-assisted laparoscopy was related to the Spigelian hernia defect.

Figure 2.

CT scan Spigelian Hernia.

We believe it is unlikely that the hand-port incision itself contributed to the development of the Spigelian hernias due to their relative anatomic separation. In addition, by virtue of the patient's right lateral decubitus position during the nephrectomy, the location of the hernia was completely obscured throughout the original procedure.

Traditional surgical repair of a Spigelian hernia is done through a gridiron incision.4 Laparoscopic techniques for repair of Spigelian hernias have also been reported.6,7 In our patient, we chose to repair the hernia through the lower midline incision created during the nephrectomy. This incision allowed for adequate exposure and visualization of the defect. The hernia defect was repaired with a Gore-Tex® patch.

Bowel obstruction following abdominal surgery would rarely be attributed to a previously undiagnosed Spigelian hernia. We postulate that our patient had a preexisting weakness in the Spigelian fascia and that the hernia developed as a result of the pneumoperitoneum. Due to the potential for asymptomatic hernias to become incarcerated due to increased intraabdominal pressure, we advise repair if discovered during laparoscopy.

References:

- 1. Jones DB, Callery MP, Soper NJ. Brief clinical report: strangulated incisional hernia at trocar site. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1996;6(2):152–154 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lajer H, Widecrantz S, Heisterberg L. Hernias in trocar ports following abdominal laparoscopy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1997;76:389–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Slakey DP, Wood JC, Hender D, Thomas R, Cheng S. Laparoscopic living donor nephrectomy: advantages of the hand-assisted method. Transplantation. 1999;68(4):581–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Spagen L. Spigelian hernia. Surg Clin North Am. 1984;64(2):351–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Agachan F, Joo JS, Weiss EG, Wexner SD. Intraoperative laparoscopic complications. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39(10):S14–S19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kasirajan K, Lopez J, Lopez R. Brief clinical report: laparoscopic technique in the management of spigelian hernia. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 1997;7(6): 385–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. DeMatteo RP, Morris JB, Broderick G. Brief clinical report: incidental laparoscopic repair of a spigelian hernia. Surgery. April 1994:521–522 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]