Abstract

Orientia tsutsugamushi is the causative agent of scrub typhus. For the diagnosis of scrub typhus, we investigated the performances of conventional PCR (C-PCR), nested PCR (N-PCR), and real-time quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) targeting the O. tsutsugamushi-specific 47-kDa gene. To compare the detection sensitivities of the three techniques, we used two template systems that used plasmid DNA (plasmid detection sensitivity), including a partial region of the 47-kDa gene, and genomic DNA (genomic detection sensitivity) from a buffy coat sample of a single patient. The plasmid detection sensitivities of C-PCR, N-PCR, and Q-PCR were 5 × 104 copies/μl, 5 copies/μl, and 50 copies/μl, respectively. The results of C-PCR, N-PCR, and Q-PCR performed with undiluted genomic DNA were negative, positive, and positive, respectively. The genomic detection sensitivities of N-PCR and Q-PCR were 64-fold and 16-fold (crossing point [Cp], 37.7; 426 copies/μl), respectively. For relative quantification of O. tsutsugamushi bacteria per volume of whole blood, we performed real-time DNA PCR analysis of the human GAPDH gene, along with the O. tsutsugamushi 47-kDa gene. At a 16-fold dilution, the copy number and genomic equivalent (GE) of GAPDH were 1.1 × 105 copies/μl (Cp, 22.64) and 5.5 × 104 GEs/μl, respectively. Therefore, the relative concentration of O. tsutsugamushi at a 16-fold dilution was 0.0078 organism/one white blood cell (WBC) and 117 organisms/μl of whole blood, because the WBC count of the patient was 1.5 × 104 cells/μl of whole blood. The sensitivities of C-PCR, N-PCR, and Q-PCR performed with blood samples taken from patients within 4 weeks of onset of fever were 7.3% (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.6 to 19.9), 85.4% (95% CI, 70.8 to 94.4), and 82.9% (95% CI, 67.9 to 92.8), respectively. All evaluated assays were 100% specific for O. tsutsugamushi. In conclusion, given its combined sensitivity, specificity, and speed, Q-PCR is the preferred assay for the diagnosis of scrub typhus.

Scrub typhus is an infectious disease caused by Orientia tsutsugamushi and is transmitted through the bite of trombiculid mites. It is a major acute febrile disease in the Asia-Pacific region (1). Fever, chills, headache, myalgia, and skin rashes occur 1 to 2 weeks after mite bites, and the occurrence of characteristic eschars is helpful for early diagnosis (18). Scrub typhus generally runs a mild clinical course and shows a good response to antibiotic therapy. However, if diagnosis is delayed, serious complications, such as interstitial pneumonia, acute renal failure, meningoencephalitis, gastrointestinal bleeding, and multiple organ failure, may develop, leading to death (10, 22–25). Thus, a method for rapid diagnosis is indispensable for successful treatment. Serologic tests such as the indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA), immunoperoxidase test, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and passive hemagglutination test (PHA) are currently in widespread use. Since these serologic tests have low sensitivities in the early stage of scrub typhus due to insufficient production of antibodies, frequent follow-up tests are needed (2). Detection of specific O. tsutsugamushi genes has been used for the rapid diagnosis of scrub typhus, and nested PCR (N-PCR) is widely used to improve the sensitivity of conventional PCR (C-PCR) (3, 4, 13). In addition, real-time quantitative PCR (Q-PCR) targeting a specific gene permits the diagnosis of scrub typhus within 2 h and has high sensitivity and specificity (5). However, there have been few studies comparing the abilities of the three aforementioned PCR methods (C-PCR, N-PCR, and Q-PCR) to detect the same O. tsutsugamushi-specific target gene. Therefore, we have compared the results of the indirect IFA, the “gold standard” test for the diagnosis of scrub typhus, to those obtained by C-PCR, N-PCR, and Q-PCR of the O. tsutsugamushi 47-kDa gene. For comparative purposes, a set of primers for the 56-kDa gene was used. Additionally, for the relative quantification of O. tsutsugamushi per volume of a patient's whole blood, we also performed real-time DNA PCR analysis of the human GAPDH gene, along with the O. tsutsugamushi 47-kDa gene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and media.

The standard bacterial strains used in this study were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), the Korea Culture Center of Microorganisms (KCCM), and the Korean Collection for Type Cultures (KCTC) (Table 1). All ordinary bacterial species used in this study were cultured on Luria-Bertani (LB) broth, brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Difco, Lawrence, KS), or LB agar (Difco). The rickettsial strains were obtained from the Australian Rickettsial Reference Laboratory (ARRL).

Table 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Pathogen |

|---|---|

| 1 | Aeromonas caviae ATCC 15468 |

| 2 | Aeromonas hydrophila subsp. hydrophila ATCC 7966 |

| 3 | Aeromonas hydrophila subsp. anaerogenes ATCC 15467 |

| 4 | Vibrio alginolyticus ATCC 17749 |

| 5 | Vibrio cholerae ATCC14035 |

| 6 | Vibrio fluvialis ATCC 33809 |

| 7 | Vibrio furnissii ATCC 35016 |

| 8 | Vibrio hollisae ATCC 33564 |

| 9 | Vibrio mimicus ATCC 33653 |

| 10 | Vibrio parahaemolyticus ATCC 17802 |

| 11 | Vibrio proteolyticus ATCC 15338 |

| 12 | Vibrio vulnificus ATCC 27562 |

| 13 | Streptococcus agalactiae ATCC 13813 |

| 14 | Streptococcus mitis ATCC 49456 |

| 15 | Streptococcus mutans ATCC 15175 |

| 16 | Streptococcus pneumoniae ATCC 33400 |

| 17 | Streptococcus pyogenes ATCC 12344 |

| 18 | Streptococcus salivarius ATCC 7073 |

| 19 | Streptococcus sanguinis ATCC 10556 |

| 20 | Streptococcus sobrinus ATCC 6715 |

| 21 | Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus (MRSAa) ATCC 33591 |

| 22 | Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) ATCC 29213 |

| 23 | Staphylococcus epidermidis ATCC 12228 |

| 24 | Staphylococcus saprophyticus subsp. saprophyticus ATCC 15305 |

| 25 | Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium KCTC 1925 |

| 26 | Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 13883 |

| 27 | Shigella sonnei ATCC 25931 |

| 28 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 |

| 29 | Clostridium perfringens ATCC 3624 |

| 30 | Aeromonas salmonicida subsp. salmonicida ATCC 33658 |

| 31 | Clostridium difficile ATCC 9689 |

| 32 | Rickettsia honei RB |

| 33 | Rickettsia rickettsii Smith |

| 34 | Rickettsia conorii 7 |

| 35 | Rickettsia akari MK (Kaplan) |

| 36 | Rickettsia prowazekii Breinl |

| 37 | Rickettsia sibirica 246 |

| 38 | Rickettsia australis JC |

| 39 | Rickettsia typhi Wilmington |

| 40 | Leptospira interrogans |

| 41 | Orientia tsutsugamushi Kato |

| 42 | Orientia tsutsugamushi Karp |

| 43 | Orientia tsutsugamushi Gilliam |

MRSA, methicillin-resistant S. aureus.

Cloning of O. tsutsugamushi 47-kDa gene and human GAPDH gene.

The 47-kDa gene was amplified using genomic DNA of the O. tsutsugamushi Karp strain as the template. The PCR conditions consisted of an initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min and 39 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 56°C, and 1 min at 72°C, with a final extension of 10 min at 72°C. The amplified 622-bp product was cloned into the pGEM-T Easy vector using T/A cloning methods. The protocol for cloning of the human GAPDH gene was the same as the protocol for cloning of the 47-kDa gene, except different primers (Gint11 and Gint12; see below) were used and human genomic DNA was used as the template. The plasmid DNA was sent to Daejeon SolGent Co., Ltd., for sequencing.

Primers and probe.

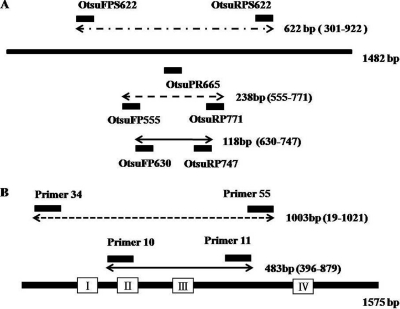

The primers and probes used in this study are summarized in Table 2. A diagram of the locations of the primers and probes is shown in Fig. 1. The probe OtsuPR665 and primers OtsuFP630 and OtsuRP747 were designed as described by Jiang et al. (5). The probe was labeled at the 5′ end with 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM) and at the 3′ end with black hole quencher 1 (BHQ-1). All primers except the Q-PCR primers and probe were designed with the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) database search program and the Primer 3 program from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (8). The 47-kDa gene assay was compared with an assay based on the nucleotide sequences of the 56-kDa antigen of a Gilliam strain of O. tsutsugamushi (3). For molecular quantification of patients' white blood cells (WBCs), we used primers Gint21 and Gint22, from intron 2 of the GAPDH gene. The Gint23 probe was labeled at the 5′ end with FAM and at the 3′ end with BHQ-1.

Table 2.

Oligonucleotide primers and a probe used in this study and PCR conditions

| Primer or probe name | Sequence | Amplicon size (bp) | Reference | PCR assay/function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OtsuFPS622 | 5′-GAAGTGTTCTTAGGTTCTGGGGTTATC-3′ | 622 | Cloning primer | |

| OtsuRPS622 | 5′-CTTTTATAACTTCAGTTATTAGAACTCC-3′ | |||

| OtsuFP555 | 5′-TCCTTTCGGTTTAAGAGGAACA-3′ | 238 | 47-kDa N-PCR external primer | |

| OtsuRP771 | 5′-GCATTCAACTGCTTCAAGTACA-3′ | |||

| OtsuPR665 (probe) | 5′-FAM-TGGGTAGCTTTGGTGGACCGATGTTTAATCT-BHQ1-3′ | 5 | 47-kDa Q-PCR probe | |

| OtsuFP630 | 5′-AACTGATTTTATTCAACTAATGCTGCT-3′ | 118 | 5 | 47-kDa Q-PCR, C-PCR, and N-PCR internal primer |

| OtsuRP747 | 5′-TATGCCTGAGTAAGATACRTGAATRGAATT-3′ | 5 | ||

| P34 | 5′-TCAAGCTTATTGCTAGATCTGC-3′ | 1,003 | 25 | 56-kDa N-PCR external primer |

| P55 | 5′-AGGGATCCCTGCTGCTGTGCTTGCTGCG-3′ | 25 | ||

| P10 | 5′-GATCAAGCTTCCTCAGCCTACTATAATGCC-3′ | 483 | 25 | 56 kDa |

| P11 | 5′-CTAGGGATCCCGACAGATGCACTATTAGGC-3′ | 455 | 25 | |

| Gint11 | 5′-TAAGTGCATGTGTGTGGGGAGA-3′ | C-PCR | ||

| Gint12 | 5′-CCGGGTGATGCTTTTCCTAGAT-3′ | N-PCR internal primer | ||

| Gint21 | 5′-GTTTATGGAGGTCCTCTTGTGTC-3′ | 90 | GAPDH cloning primer | |

| Gint22 | 5′-ACTACCCATGACTCAGCTTCTC-3′ | GAPDH Q-PCR | ||

| Gint23 (probe) | 5′-FAM-ACCATGCCACAGCCACCACACCT-BHQ1-3′ |

Fig. 1.

(A) Locations of the selected primers and probes in the 47-kDa outer membrane protein gene (strain Kato, GenBank accession number L11697). External primers OtsuFR555 and OtsuRP771 were used to amplify a 238-bp segment of the O. tsutsugamushi-specific 47-kDa gene, and internal primers OtsuFP630 and OtsuRP747 were used to amplify a 118-bp segment. The probe OtsuPR665 was used for Q-PCR. (B) Locations of the selected primers in the 56-kDa outer membrane protein gene (strain Gilliam, GenBank accession number L31933). External primers p34 and p55 were used to amplify a 1,003-bp segment of the O. tsutsugamushi-specific 56-kDa gene, and internal primers p10 and p11 were used to amplify an internal 483-bp segment. The open reading frame of the 56-kDa gene is represented by a heavy line, and boxes I, II, III, and IV indicate the variable domains.

PCRs. (i) C-PCR.

Bacterial DNA was extracted using a QIAamp DNA minikit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturer's instructions, and was used as the template for the PCR. The C-PCR targeting the 47-kDa gene was performed in 20-μl reaction volumes containing 10 μl of 2× Excel Taq premix (Corebiosystems, Seoul, South Korea), 2 μl of the template DNA, and 1 μl each (5 pmol) of the OtsuFP630 and OtsuRP747 primers. The PCR conditions consisted of denaturation at 94°C for 10 min, followed by 30 cycles, each consisting of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 60°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 1 min. The final elongation step was prolonged for 7 min at 72°C. Additionally, the 56-kDa gene C-PCR was performed in 20-μl reaction volumes containing 2 μl of template DNA, 5 pmol of each primer (P10 and P11), and 10 μl of 2× Excel Taq premix (Corebiosystems). The PCR conditions consisted of an initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 63°C for 1 min, and extension at 72°C for 1 min. The final elongation step was prolonged for 7 min at 72°C.

(ii) N-PCR.

The first round of N-PCR for the amplification of the 47-kDa gene was performed under the same conditions used for the C-PCRs, except that the annealing step was at 56°C for 1 min and 10 pmol of each primer (OtsuFP555 and OtsuRP771) was used. The second round of N-PCR for the 47-kDa gene was performed using the first PCR product as the template DNA and 10 pmol/μl of each primer (OtsuFP630 and OtsuRP747). The second-round PCR conditions involved an initial denaturation at 94°C for 10 min, followed by 25 cycles, each consisting of denaturation at 94°C for 30s, annealing at 60°C for 30s, and extension at 72°C for 1 min, with a final extension for 7 min at 72°C.

The first round of N-PCR for the 56-kDa gene was performed under the same conditions used for the C-PCRs, except the annealing step was performed at 61°C and 5 pmol/μl of each primer (P34 and P55) was used. The second round of N-PCR for the 56-kDa gene was performed using the first-round PCR product as the template DNA and 5 pmol/μl of each primer (P10 and P11). The second-round PCR conditions involved an initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min and 30 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 63°C, and 1 min at 72°C, with a final extension for 7 min at 72°C.

(iii) Q-PCR.

We performed the same protocols for Q-PCR of the O. tsutsugamushi 47-kDa and human GAPDH genes. Plasmid DNA of O. tsutsugamushi or human GAPDH was quantified with a spectrophotometer (DU 530 Life Science UV/visible spectrometer; Beckman Coulter). A standard curve was generated on the basis of serial dilutions of a net suspension of 1 μl of 108 copies/μl of plasmid DNA. Q-PCRs were run in 20-μl reaction volumes containing 5 μl of DNA, 1 μl (5 pmol/μl) of each primer, 1 μl of probe at 2 pmol/μl, 4 μl of 5× master mix (reaction buffer, Fast Start Taq DNA polymerase, MgCl2 and deoxynucleoside triphosphates [with dUTP instead of dTTP]), and distilled water (D/W). The PCR conditions consisted of an initial activation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 45 cycles of 10 s at 95°C and 30 s at 60°C. The second derivative (crossing point [Cp]), which calculates the fractional cycle where the Cp of the Q-PCR fluorescence intensity curve reaches its maximum value, was utilized for the assay analysis. The data for the Q-PCR were analyzed using the LightCycler software program (version 4.0). The O. tsutsugamushi data in ng/μl were then converted to numbers of copies/μl.

Detection sensitivity.

We compared the detection sensitivities of the three techniques using plasmid DNA (plasmid detection sensitivity) and genomic DNA (genomic detection sensitivity). For plasmid detection sensitivity, we performed Q-PCR, N-PCR, and C-PCR with serial dilutions of plasmid DNA from 5 × 108 copies/μl to 5 × 10−3 copies/μl using sterile D/W. For genomic detection sensitivity, we performed Q-PCR, N-PCR, and C-PCR with serial dilutions of genomic DNA from undiluted to a 64-fold dilution. For serial dilutions of genomic DNA from the buffy coat of an O. tsutsugamushi-infected patient, we used genomic DNA from a buffy coat sample of whole blood from an individual not infected with O. tsutsugamushi.

Relative quantification of O. tsutsugamushi in whole blood.

For relative quantification of O. tsutsugamushi bacteria per volume of whole blood, we performed real-time DNA PCR analysis of the human GAPDH gene, along with the O. tsutsugamushi 47-kDa gene. Each of the diluted genomic DNA samples (undiluted to 64-fold dilution) with different concentrations of O. tsutsugamushi was used for Q-PCR to quantify the dosages of the O. tsutsugamushi 47-kDa gene and human GAPDH gene in two separate tubes. We calculated the relative quantity of O. tsutsugamushi in patients' whole blood using the genomic equivalent (GE) of GAPDH and WBC counts.

Specificity test.

For the specificity test, bacterial cells grown on brain heart infusion broth and LB agar were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) to 1 × 108 CFU/ml. Bacterial DNA was extracted from 200 μl of the suspension, using the QIAamp DNA minikit (Qiagen), following the manufacturer's instructions.

Patient selection.

Specimens from patients aged 18 years or older who visited Chosun University Hospital within 4 weeks of fever onset had been collected between 2005 and 2007 and stored (6, 7). Scrub typhus was defined as a 4-fold or greater increase in antibody titers by IFA. Non-scrub typhus specimens were selected on the basis of negative results by culture and peripheral blood smear and the absence of IFA antibodies against O. tsutsugamushi. Infectious disease specialists randomly selected 41 patients with scrub typhus and 52 patients without scrub typhus and sent blood samples to our laboratory. The blood buffy coat specimens were processed and tested blindly by the PCR assays for the 56-kDa and 47-kDa genes of O. tsutsugamushi.

Statistical analysis.

The sensitivities and specificities of the PCR assays were analyzed using the MedCalc software program (Mariakerke, Belgium) (20). Statistical significance was bestowed on data with P values of <0.05. A 4-fold or more increase in antibody titer against O. tsutsugamushi, as measured by IFA, was used to evaluate sensitivity and specificity under the receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve. The diagnostic accuracies of the three PCR assays were compared using the MedCalc software program (20).

RESULTS

Detection sensitivity.

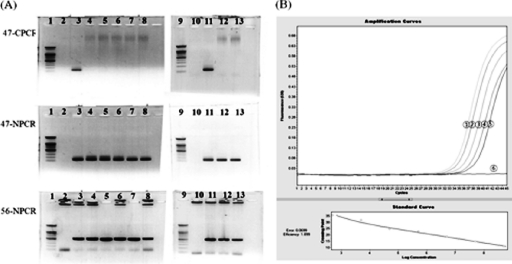

The plasmid detection sensitivities of C-PCR, N-PCR, and Q-PCR were 5 × 104 copies/μl, 5 copies/μl, and 50 copies/μl, respectively (data not shown). However, in the detection sensitivity system using genomic DNA, the detection sensitivities of N-PCR and Q-PCR were 64-fold and 16-fold, respectively (Cp, 37.7; 426 copies/μl of genomic DNA from a buffy coat sample), but C-PCR could not detect the 47-kDa gene of O. tsutsugamushi in undiluted genomic DNA from a buffy coat sample (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

(A) Detection sensitivities of C-PCR and N-PCR. Lane 1, 100-bp ladder marker (Bioneer); lane 2, negative control (sterile distilled water); lane 3, positive-control strain Karp; lane 4, undiluted genomic DNA; lane 5 to lane 8, from 2-fold-diluted genomic DNA to 16-fold-diluted genomic DNA, respectively; lane 9, 100-bp ladder marker (Bioneer); lane 10, sterile D/W; lane 11, positive-control strain Karp; lane 12 and lane 13, from 32-fold-diluted genomic DNA and 64-fold-diluted genomic DNA, respectively; 47-kDa C-PCR (47-CPCR) and 47-kDa N-PCR (47-NPCR) target size, 118 bp; 56-kDa N-PCR (56-NPCR) target size, 483 bp. (B) Detection sensitivities of Q-PCR. Circle 1, undiluted genomic DNA (Cp, 33.30); circle 2, 2-fold-diluted genomic DNA (Cp, 34.01); circle 3, 4-fold-diluted genomic DNA (Cp, 35.21); circle 4, 8-fold diluted genomic DNA (Cp, 36.19); circle 5, 16-fold-diluted genomic DNA (Cp, 37.47); circle 6, D/W. The results of Q-PCR using 32-fold- and 64-fold-diluted genomic DNA were negative (Cp, 39.36 and >40.00, respectively) due to use of a cutoff value of >38 (data not shown).

Relative quantification of O. tsutsugamushi in whole blood.

At the 16-fold dilution, the copy number and GE of GAPDH were 1.1 × 105 copies/μl (Cp, 22.64) and 5.5 × 104 GEs/μl, respectively. Therefore, the relative concentration of O. tsutsugamushi at a 16-fold dilution was 0.0078 organism/one WBC cell and 117 organisms/μl of whole blood, because the WBC count of the patient was 1.5 × 104 cells/μl of whole blood.

Detection specificity.

The detection specificities of the 47-kDa and 56-kDa PCR assays were assessed using various rickettsial DNAs and various other bacterial DNAs. C-PCR and N-PCR of the type strains did not give rise to any bands other than those for O. tsutsugamushi (data not shown). Q-PCR showed high Cp values (>30) for all strains except the O. tsutsugamushi Gilliam (Cp, 20.09), Karp (Cp, 23.22), and Kato (Cp, 23.02) strains (data not shown).

Sensitivity and specificity using patient blood samples.

In scrub typhus patients, C-PCR targeting the 47-kDa gene gave a positivity rate of 7% (3/41 samples). In contrast, N-PCR targeting the same gene gave a positivity rate of 85% (35/41). However, none of the non-scrub typhus patients showed positivity by either C-PCR or N-PCR assay. If we adopted a negative-cutoff value of 38 Cp for Q-PCR using patients' blood (8, 15–17), the Q-PCR yielded positivity rates of 83% (34/41) in patients with scrub typhus and 0% (0/52) in those without scrub typhus. Although C-PCR targeting the 56-kDa gene was not positive for any of the 41 patients with scrub typhus, N-PCR yielded a positivity rate of 87.8% (36/41). Neither C-PCR nor N-PCR was positive for patients without scrub typhus.

Comparison of the diagnostic accuracies of the three assays in patients with scrub typhus.

In the scrub typhus patients, the C-PCR for the 47-kDa gene had a sensitivity of 7.3% (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.6 to 19.9) and a specificity of 100% (95% CI, 87.9 to 100). In contrast, the N-PCR had a sensitivity of 85.4% (95% CI, 70.8 to 94.4) and a specificity of 100% (95% CI, 93.1 to 100). If we adopted a negative-cutoff value of 38 Cp for the Q-PCR, it had a sensitivity of 82.9% (95% CI, 67.9 to 92.8) and a specificity of 100% (95% CI, 93.1 to 100).

The areas under the curve (AUCs) for the 47-kDa N-PCR and Q-PCR were 0.93 (95% CI, 0.84 to 0.98; P = 0.743) and 0.92 (95% CI, 0.82 to 0.97), respectively. However, the AUC of C-PCR for the 47-kDa gene was 0.54 (95% CI, 0.41 to 0.66), which was significantly different from the AUCs of Q-PCR and N-PCR (Q-PCR versus C-PCR, P < 0.001; N-PCR versus C-PCR, P < 0.001). On the other hand, the 56-kDa C-PCR had a sensitivity of 0% (95% CI, 0 to 8.7), a specificity of 100% (95% CI, 93.1 to 100), and an AUC of 0.55 (95% CI, 0.44 to 0.65), which were not significantly different from those of the 47-kDa C-PCR (47-kDa C-PCR versus 56-kDa C-PCR, P = 0.67). The 56-kDa N-PCR had a sensitivity of 87.8% (95% CI, 73.8 to 95.9), a specificity of 100% (95% CI, 93.1 to 100), and an AUC of 0.94 (95% CI, 0.87 to 0.98), which, again, were not statistically different from those of the 47-kDa N-PCR (47-kDa N-PCR versus 56-kDa N-PCR, P = 0.67).

DISCUSSION

Scrub typhus runs a mild clinical course and responds well to proper antibiotic therapy. However, in patients with a delayed diagnosis, it may cause fatal complications (21). Thus, a rapid diagnosis of scrub typhus is essential for successful treatment. PCR assays have been widely used for rapid identification of fastidious organisms or rickettsiae that are difficult to cultivate. Murai et al. (13) have reported that C-PCR requires 20 ng of DNA for detection. As N-PCR requires only 200 pg of DNA, N-PCR is 100 times more sensitive than C-PCR. Q-PCR is useful for rapid diagnosis of scrub typhus because it takes only 2 h and it is helpful in evaluating the response to treatment and clinical outcome. However, Q-PCR has the disadvantage of high financial cost. N-PCR also has some disadvantages: it requires more time than Q-PCR or C-PCR, and there is a higher risk of spurious results due to DNA contamination (12). There have been few studies comparing the diagnostic accuracies of C-PCR, N-PCR, and Q-PCR against the same target gene specific for O. tsutsugamushi. We selected the 47-kDa gene, which encodes an outer membrane protein/antigen also known as the high-temperature-requirement A protein (HtrA), as the target DNA, since this was the only gene for which well-verified real-time PCR results were available (5). The htrA gene is induced by environmental stress, such as high temperature, and proteins of this family from Escherichia coli, Rickettsia prowazekii, Haemophilus influenzae, Brucella abortus, and even eukaryotic organisms, including humans, are known (9).

Primers OtsuFP630 and OtsuRP747 were designed on the basis of the 47-kDa gene sequence, which is conserved in the Karp, Kato, Gilliam, Boryong, and TH187 strains of O. tsutsugamushi. The sequence is not detected in the htrA genes of other genera related to Rickettsia or its human homologues. For Q-PCR, the Cp values adopted for cultured organisms are usually lower than those adopted for clinical specimens, such as blood, tissue, fluid, and biopsy samples (15–17). Generally, a Cp value of >30 or >28 is regarded as a negative result for Q-PCR of cultured organisms, whereas a Cp value of >40 or >38 is regarded as a negative result for Q-PCR of clinical specimens, such as blood, stool, and biopsy samples (8, 19). We adopted a Cp value of >38 as a negative outcome for Q-PCR of blood and a cutoff Cp value of >30 for Q-PCR of cultured bacterial and rickettsial isolates. The 47-kDa gene cloned into plasmid DNA was detected at up to a dilution of 5 × 104 copies/μl by C-PCR and 5 copies/μl by N-PCR. Plasmid DNA could also be detected down to 50 copies/μl under the same conditions as the Q-PCR. However, plasmid gene copies are of little value, as these do not represent true sensitivity generalized to clinical samples. Therefore, we selected buffy coat samples from a scrub typhus patient to determine true detection sensitivities. The genomic detection sensitivity of Q-PCR targeting the 47-kDa gene was 16-fold (Cp, 37.7; 426 copies/μl of genomic DNA from a buffy coat using plasmid standard curves). N-PCR targeting the 47-kDa and 56-kDa genes showed similar sensitivities, with detection at up to a 64-fold dilution (Fig. 2A and B).

For relative quantification of O. tsutsugamushi bacteria per volume of whole blood, we also performed real-time DNA PCR analysis of the human GAPDH gene, along with the O. tsutsugamushi 47-kDa gene. The general idea of this analysis was induced from enumeration of the malaria parasite density in peripheral blood smears using the WBC count as a reference (24). The genomic detection sensitivity for relative quantification using the WBC count (1.5 × 104 cells/μl) as a reference was 117 organisms/μl of whole blood. In clinical practice, for patients with scrub typhus, C-PCR and N-PCR targeting the 47-kDa gene gave positivity rates of 7% (3/41) and 85% (35/41), respectively. According to our detection sensitivity data and comparison of the results of molecular assays using patient blood samples, this study showed that N-PCR is much more sensitive than C-PCR for the diagnosis of scrub typhus. If we adopted a negative-cutoff value of >38 Cp for Q-PCR using patients' blood, Q-PCR had 83% (34/41) positivity for scrub typhus patients and 0% (0/52) for non-scrub typhus patients. N-PCR and Q-PCR targeting the 47-kDa gene gave false-negative results for 6 and 7 out of the 41 patients with scrub typhus, respectively (data not shown). If we exclude one patient who was positive for N-PCR but negative for Q-PCR, the results of N-PCR were concordant with those of Q-PCR in all patients (data not shown). It is generally recognized that the 56-kDa protein is the major cell membrane antigen of O. tsutsugamushi and the major immunodominant antigen. It has been widely used to diagnose scrub typhus because it contains both group-specific and type-specific epitopes (14).

Since the 56-kDa gene is used much more frequently in clinical practice than the 47-kDa gene, we also compared the C-PCR and N-PCR results for the 47-kDa gene with those for the 56-kDa gene. C-PCR targeting the 56-kDa gene was negative for all 41 patients with scrub typhus; however, N-PCR for the same target gene showed a positivity rate of 87.8%. The results of the C-PCR and N-PCR assays for the 56-kDa gene were not significantly different from those for the 47-kDa gene.

In conclusion, Q-PCR and N-PCR targeting the O. tsutsugamushi-specific 47-kDa gene are more sensitive than C-PCR for detection of the organism in patients with suspected scrub typhus. In particular, Q-PCR is the assay of choice, as amplicon containment is easier to achieve and the rapid turnover of the assay gives it the edge over the other assays.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We do not have any commercial interest or other association that might pose a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 10 November 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1. Blacksell S. D., Bryant N. J., Paris D. H., Doust J. A., Sakoda Y., Day N. P. 2007. Scrub typhus serologic testing with the indirect immunofluorescence method as a diagnostic gold standard: a lack of consensus leads to a lot of confusion. Clin. Infect. Dis. 44:391–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bozeman G. W., Elisberg B. L. 1963. Serological diagnosis of scrub typhus by indirect immunofluorescence. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 112:568–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Furuya Y., Yoshida Y., Katayama T., Kawamori F., Yamamoto S., Ohashi N., Tamura A., Kawamura A. 1991. Specific amplification of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi DNA from clinical specimens by polymerase chain reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:2628–2630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Horinouchi H., Murai K., Okayama A., Nagatomo Y., Tachibana N., Tsubouchi H. 1996. Genotypic identification of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of DNA amplified by the polymerase chain reaction. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 54:647–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jiang J., Chan T. C., Temenak J. J., Dasch G. A., Ching W. M., Richards A. L. 2004. Development of a quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction assay specific for Orientia tsutsugamushi. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 70:351–356 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim D.-M., Byun J. N. 2008. Effects of antibiotic treatment on the results of nested PCRs for scrub typhus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:3465–3466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kim D. M., Yu K. D., Lee J. H., Kim H. K., Lee S. H. 2007. Controlled trial of a 5-day course of telithromycin versus doxycycline for treatment of mild to moderate scrub typhus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51:2011–2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kim H. S., Kim D. M., Neupane G. P., Lee Y. M., Yang N. W., Jang S. J., Jung S. I., Park K. H., Park H. R., Lee C. S., Lee S. H. 2008. Comparison of conventional, nested, and real-time PCR assays for a rapid and accurate detection of Vibrio vulnificus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46:2992–2998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kim J. H., Hahn M. J. 2000. Cloning and sequencing of the gene encoding the candidate HtrA of Rickettsia typhi. Microb. Immunol. 44:275–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kim S. J., Chung I. K., Chung I. S., Song D. H., Park S. H., Kim H. S., Lee M. H. 2000. The clinical significance of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy in gastrointestinal vasculitis related to scrub typhus. Endoscopy 32:950–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reference deleted.

- 12. Lee S. E., Kim S. Y., Kim S. J., Kim H. S., Shin J. H., Choi S. H., Chung S. S., Rhee J. H. 1998. Direct identification of Vibrio vulnificus in clinical specimens by nested PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36:2887–2892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Murai K., Tachibana N., Okayama A., Shishime E., Tsuda K., Oshikawa T. 1992. Sensitivity of polymerase chain reaction assay for Rickettsia tsutsugamushi in patients' blood samples. Microbiol. Immunol. 36:1145–1153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ohashi N., Nashimoto H., Ikeda H., Tamura A. 1992. Diversity of immunodominant 56-kDa type-specific antigen (TSA) of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi. Sequence and comparative analyses of the genes encoding TSA homologues from four antigenic variants. J. Biol. Chem. 267:12728–12735 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Perellea S., Josefsenb M., Hoorfarb J., Dilassera F., Grouta J., Fach P. 2004. A LightCycler real-time PCR hybridization probe assay for detecting food-borne thermophilic Campylobacter. Mol. Cell. Probes 18:321–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Poppert S., Essig A., Stoehr B., Steingruber A., Wirths B., Juretschko S., Reischl U., Wellinghausen N. 2005. Rapid diagnosis of bacterial meningitis by real-time PCR and fluorescence in situ hybridization. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:3390–3397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rodríguez-Lázaroa D., Hernándezb M., Esteveb T., Hoorfarc J., Pla M. 2003. A rapid and direct real time PCR-based method for identification of Salmonella spp. J. Microbiol. Methods 54:381–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Saini R., Pui J. C., Burgin S. 2004. Rickettsialpox: report of three cases and a review. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 51:S137–S142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schabereiter-Gurtner C., Hirschl A. M., Dragosics B., Hufnagl P., Puz S., Kovách Z., Rotter M., Makristathis A. 2004. Novel real-time PCR assay for detection of Helicobacter pylori infection and simultaneous clarithromycin susceptibility testing of stool and biopsy specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:4512–4518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shidham V., Gupta D., Galindo L. M., Haber M., Grotkowski C., Edmonds P., Subichin S. J., George V., England J. 2000. Intraoperative scrape cytology: comparison with frozen sections, using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Diagn. Cytopathol. 23:134–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Silpapojakul K., Chupuppakarn S., Yuthasompob S., Varachit B., Chaipak D., Borkerd T., Silpapojakul K. 1991. Scrub and murine typhus in children with obscure fever in the tropics. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 10:200–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Thap L. C., Supanaranond W., Treeprasertsuk S., Kitvatanachai S., Chinprasatsak S., Phonrat B. 2002. Septic shock secondary to scrub typhus: characteristics and complications. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 33:780–786 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tsay R. W., Chang F. Y. 1998. Serious complications in scrub typhus. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 31:240–244 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Warhurst D. C., Williams J. E. 1996. ACP broadsheet no 148. July 1996. Laboratory diagnosis of malaria. J. Clin. Pathol. 49:533–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yen T. H., Chang C. T., Lin J. L., Jiang J. R., Lee K. F. 2003. Scrub typhus: a frequently overlooked cause of acute renal failure. Ren. Fail. 25:397–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]