Abstract

A high (11.8%) level of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection was found among 524 Pygmies in Cameroon, whereas the extent of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in the same population was low (0.6%). Phylogenetic analyses showed cocirculation of two HBV genotypes, HBV-A3 and -E. Taken together, our results suggest different epidemiological scenarios concerning HBV and HCV infections in this population.

Sub-Saharan Africa is considered to be an area of high hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) endemicity (6, 11). However, to date little information has been available pertaining to the prevalence and genetic diversity of these viruses in central Africa. In Cameroon, HBV and HCV infections have been studied mostly among Bantu populations (4, 13, 15), and very few data are available for the Pygmies in this region. The Pygmies have lived in a forest environment in Cameroon for more than 20,000 years, mostly as hunter-gatherers (19). The characterization of HBV and HCV isolates from ancient populations may help to reveal the origin and evolutionary history of these viruses (7). Three distinct Pygmy groups currently live in Cameroon: the Baka, the Bakola, and the Bedzan. Three studies conducted 15 years ago reported a high HCV prevalence, ranging from 6 to 11%, in the Pygmy population (5, 10, 12). However, these studies only considered the Baka. Furthermore, the performances of the tests used at that time are questionable. A more recent study demonstrated an HCV prevalence of only 2.3% (8). In those 4 studies, Cameroon was found to be an area where HBV is highly endemic. Even now, no comparable information is available for the Bakola or Bedzan Pygmies. Thus, the objectives of our study were to assess the prevalence of HBV and HCV markers among the three Pygmy groups from Cameroon and also to study the HBV genetic diversity in these populations.

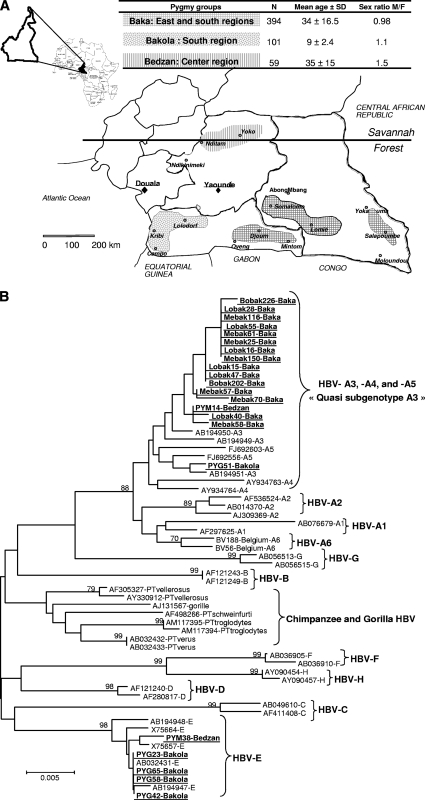

This study formed part of a survey of viral emergence in Pygmies from Cameroon conducted from 2005 to 2008 (1–3). Informed consent was obtained from adults (or from parents, in the case of children) before blood sampling. Furthermore, the participants of the study underwent a medical examination and, if necessary, were treated according to local procedures on site or were sent to local medical facilities. The geographic localization, the number of subjects included in each group, the mean age, and the sex ratio are shown in Fig. 1A.

Fig. 1.

(A) Map of Cameroon showing the localization of the three ethnic groups of pygmies. The number of subjects included in each group (N), the mean age, and the sex ratio are indicated in the table. The Baka group is the largest (40,000 to 45,000 individuals), and its distribution overlaps the two administrative regions of the south and the east. The Bakola pygmies are the next most populous group (4,000 to 5,000 individuals), and they are mostly located in the western part of the southern region in the Atlantic Ocean division. The Bedzan group is the smallest (700 to 1,000 individuals) and is located in the northern part of the central region. (B) Phylogenetic neighbor-joining tree constructed using the sequences of a 423-bp fragment of the HBV S gene from 22 HBV isolates (GenBank accession numbers HM355550 to HM355571) from Baka, Bakola, and Bedzan pygmies (highlighted in boldface and underlined) and 49 GenBank sequences of HBV-A to -H genotypes and chimpanzee and gorilla HBV genotypes (GenBank accession numbers and genotypes are indicated). Numbers next to the nodes of the tree represent bootstrap values (100 replicates). Only bootstrap values above 70 are presented.

The presence of antibodies against HCV (anti-HCV) was checked by the use of a third-generation enzyme immunoassay (EIA) (Monolisa anti-HCV Plus version 2; Bio-Rad, Marne-La-Coquette, France). A positive result for anti-HCV was defined as a Monolisa ratio of greater than 6 (16). Of the 346 available samples tested, only 2 (0.6%) (one Baka and one Bedzan; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.9 to 1.9%) were anti-HCV positive. Those samples were negative when tested for HCV RNA.

HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) was screened for by a third-generation EIA (Monolisa AgHBs Plus; Bio-Rad). Of the 524 samples tested, 62 (11.8%) (95% CI, 9.2 to 14.9%) were positive. The prevalence rates of HBsAg were not statistically different between the three ethnic groups over the same age range. However, in the Baka population, there was a significant association between a decrease in HBsAg and an increase in age, dropping from 23.5% in the ≤10-year-old group to 6.6% in the >50-year-old population (P < 0.001) (Table 1). Subsequent to their use in a larger epidemiological survey in the same population (1–3), not all samples were available for molecular analyses. A 423-bp fragment of the HBV S gene was amplified as described previously (18) and sequenced from 22 HBsAg-positive serum samples (from 15 Baka, 5 Bakola, and 2 Bedzan individuals). After sequence alignment, 17 (77.3%) sequences were seen to belong to the HBV-A3 subgenotype and 5 (22.7%) to the HBV-E genotype. Interestingly, the 15 sequences from Baka individuals were all of the HBV-A3 subgenotype, whereas there was cocirculation of HBV-A3 and HBV-E sequences in the Bakola and Bedzam groups, with the HBV-E genotype being predominant (80%) among members of the Bakola population (Fig. 1B). The 17 HBV-A3 subgenotype sequences clustered with previously reported HBV-A4 and -A5 subgenotypes (17), although this observation was not supported by a high bootstrap value. This group was designated the “quasi-A3 subgenotype.”

Table 1.

Prevalence of HBsAg in Pygmy populations in Cameroon, divided according to ethnic group and age range

| Age range (yr) | No. of positive samples for indicated population/no. tested (%; 95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baka | Bakola | Bedzan | Total | |

| ≤10 | 4/17 (23.5; 6.8–49.9) | 13/66 (19.7; 10.9–31.2) | 0 | 17/83 (20.5; 12.4–30.8) |

| 11–20 | 9/69 (13.0; 6.1–23.3) | 6/35 (17.1; 6.6–33.6) | 1/9 (11.1; 0.2–48.2) | 16/113 (14.2; 8.3–22.0) |

| 21–30 | 10/89 (11.2; 5.5–19.7) | 0 | 2/20 (10.0; 1.2–31.7) | 12/109 (11.0; 5.8–18.4) |

| 31–40 | 6/80 (7.5; 2.8–15.6) | 0 | 3/13 (23.1; 5.0–53.8) | 9/93 (9.7; 4.5–17.6) |

| 41–50 | 4/49 (8.2; 2.3–19.6) | 0 | 0/8 | 4/57 (7.0; 1.9–17.0) |

| >50 | 4/60 (6.6; 1.8–16.2) | 0 | 0/9 | 4/69 (5.8; 1.6–14.2) |

| Total | 37/364 (10.2; 7.3–13.7) | 19/101 (18.8; 11.7–27.8) | 6/59 (10.2; 3.8–20.8) | 62/524 (11.8; 9.2–14.9) |

The present study confirms the very low rate of HCV infection of the Baka in Cameroon (8) and extends this conclusion to the Bakola and Bedzan populations. Such a low viral prevalence, especially among elderly pygmies (people aged above 50 years), contrasts with the high rates found among the neighboring Bantu populations (5, 8, 10, 13, 15) and points to a different route or different dynamics of HCV transmission in Cameroon. One hypothesis is that transmission among the Bantu in the past had occurred during mass treatment and vaccination with unsafe material (14).

The prevalence of HBsAg noted in our study was comparable to that reported previously in studies of the Baka (8, 12), was similar to that reported for Bantu populations (4, 8), and indicated that Cameroon is an area where HBV is highly endemic. The age-dependent HBsAg prevalence profile showing that the population of children under 10 years of age experienced a high rate of infection strongly suggested perinatal transmission or transmission in early childhood. Systematic HBV screening during pregnancy is not yet practiced in Cameroon. Furthermore, the expanded child vaccination program introduced into Cameroon in 2005 is limited to urban areas. To prevent the spread of HBV, these programs must be extended to all remote parts of the country.

From a molecular point of view, our data confirm the cocirculation of HBV-A3 and HBV-E genotypes in Pygmies living in Cameroon (8). Interestingly, Baka Pygmies were infected only by the HBV-A3 subgenotype, whereas the HBV-E genotype was predominant in the Bakola population. Despite the relatively small sample size, the different HBV genotypes present in Baka versus Bakola Pygmies raise questions regarding the origin of these viruses. The high prevalence of the HBV-A3 subgenotype, and its presence in the three groups of Pygmy, suggests a protracted natural history of this subgenotype in Cameroon, whereas the low prevalence of the HBV-E genotype may indicate recent introduction into this area. These results are in agreement with previous studies that reported a central African origin for the HBV A3 subgenotype and a west African origin for HBV-E (9). It is also notable that even though Pygmies still frequently hunt, none of the recent HBV isolates are related to HBV genotypes from chimpanzee or gorilla, suggesting the absence of cross-species transmission of this virus. This situation contrasts with that observed for foamy retroviruses in the same populations (2).

In conclusion, our data demonstrate a low prevalence of HCV infection among Pygmies living in Cameroon, reinforcing the hypothesis of a massive iatrogenic transmission of HCV in neighboring Bantu populations. Furthermore, our results extend to HBV infection the previous findings demonstrating that Cameroon is an area of high HCV endemicity for the 3 Pygmy groups. HBV-A3 appears to be a longstanding, indigenous HBV strain in Cameroon. Further studies designed to extensively characterize HBV strains from other indigenous populations in central Africa should reveal new insights into the origin and the evolutionary history of this oncovirus.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank accession numbers of the HBV-A3 subgenotype and HBV-E genotype sequences described in this study are HM355550 to HM355571.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the members of the three Pygmy ethnic groups who agreed to participate in this study. We are also grateful to Jean-Marc Reynes and Anfumbom Jude Kfutwah for critical reading of the manuscript. The authors also thank Katherine Kean from the Pasteur Institute in Paris for language correction.

This work was funded by the Centre Pasteur of Cameroon and the Unité d'Epidémiologie et Physiopathologie des Virus Oncogènes of Institut Pasteur, Paris, France.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 24 November 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1. Calattini S., et al. 2009. New strain of human T lymphotropic virus (HTLV) type 3 in a Pygmy from Cameroon with peculiar HTLV serologic results. J. Infect. Dis. 199:561–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Calattini S., et al. 2007. Simian foamy virus transmission from apes to humans, rural Cameroon. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 13:1314–1320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Calattini S., et al. 2005. Discovery of a new human T-cell lymphotropic virus (HTLV-3) in Central Africa. Retrovirology 2:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chiaramonte M., et al. 1991. Hepatitis B virus infection in Cameroon: a seroepidemiological survey in city school children. J. Med. Virol. 33:95–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kowo M. P., et al. 1995. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus and other blood-borne viruses in Pygmies and neighbouring Bantus in southern Cameroon. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 89:484–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kramvis A., Kew M. 2007. Epidemiology of hepatitis B virus in Africa, its genotypes and clinical associations of genotypes. Hepatol. Res. 37:S9–S19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kramvis A., Kew M., François G. 2005. Hepatitis B virus genotypes. Vaccine 23:2409–2423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kurbanov F., et al. 2005. A new subtype (subgenotype) Ac (A3) of hepatitis B virus and recombination between genotypes A and E in Cameroon. J. Gen. Virol. 86:2047–2056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kurbanov F., Tanaka Y., Mizokami M. 2010. Geographical and genetic diversity of the human hepatitis B virus. Hepatol. Res. 40:14–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Louis F. J., Maubert B., Le Hesran J. Y., Kemmegne J., Delaporte E., Louis J. P. 1994. High prevalence of anti-hepatitis C virus antibodies in a Cameroon rural forest area. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 88:53–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Madhava V., Burgess C., Drucker E. 2002. Epidemiology of chronic hepatitis C virus infection in sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2:293–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ndumbe P. M., Atchou G., Biwole M., Lobe V., Ayuk-Takem J. 1993. Infections among pygmies in the Eastern Province of Cameroon. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 182:281–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nerrienet E., et al. 2005. Hepatitis C virus infection in Cameroon: a cohort-effect. J. Med. Virol. 76:208–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Njouom R., et al. 2007. The hepatitis C virus epidemic in Cameroon: genetic evidence for rapid transmission between 1920 and 1960. Infect. Genet. Evol. 7:361–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Njouom R., et al. 2003. High rate of hepatitis C virus infection and predominance of genotype 4 among elderly inhabitants of a remote village of the rain forest of South Cameroon. J. Med. Virol. 71:219–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Njouom R., et al. 2003. Hepatitis C virus infection among pregnant women in Yaounde, Cameroon: prevalence, viremia, and genotypes. J. Med. Virol. 69:384–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pourkarim M. R., Amini-Bavil-Olyaee S., Lemey P., Maes P., Van Ranst M. 2010. Are hepatitis B virus “subgenotypes” defined accurately? J. Clin. Virol. 47:356–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Starkman S. E., MacDonald D. M., Lewis J. C., Holmes E. C., Simmonds P. 2003. Geographic and species association of hepatitis B virus genotypes in non-human primates. Virology 314:381–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Verdu P., et al. 2009. Origins and genetic diversity of pygmy hunter-gatherers from Western Central Africa. Curr. Biol. 19:312–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]