Detailed in this report is the laparoscopic removal of a gastric bezoar through an anterior wall gastrotomy.

Keywords: Trichobezoar, Management, Laparoscopy, Surgical technique

Abstract

A seventeen-year-old female presented with a symptomatic abdominal mass that was diagnosed by barium meal and computed tomography to be a gastric bezoar. She underwent laparoscopic removal of the bezoar, through an anterior wall gastrostomy in an endobag, which was extracted piecemeal through a 4-cm upper midline incision.

The technique is described with a review of a few previous laparoscopic-assisted cases.

INTRODUCTION

Gastric bezoars are foreign bodies in the stomach that increase in size due to accumulation of nonabsorbable food or fibers. More than 90% of cases are in children and young females.1 Traditionally, bezoars are removed by laparotomy; however, because of recent reports, laparoscopic removal is slowly growing as the choice of intervention.

CASE REPORT

A 17-year-old female came to our outpatient surgery department with a lump and dragging pain in her upper abdomen. She was malnourished with thin brittle hair and was mildly pale. A well-defined, nontender mass was palpated in the epigastrium, which was tubular in shape extending from the left subcostal margin to the right lumbar region. The upper margin of the lump was extending below the left costal margins and could not be appreciated. The patient had no history of vomiting, hematemesis, or melena. The rest of her general and abdominal examination was unremarkable. Abdominal ultrasonography showed an echogenic mass in the stomach; however, no definite diagnosis could be made. The patient's barium meal showed a mottled filling defect with entrapped air predominantly in the body and antrum with minimal extension into the pylorus and duodenum suggesting a Trichobezoar (Figure 1). She underwent contrast enhanced computed tomography of the abdomen (CECT), which showed a nonenhancing mixed density intraluminal gastric mass with foci of air and oral contrast. The mass was circumscribed by oral contrast, suggesting a trichobezoar (Figure 2). An endoscopy was also done to confirm the diagnosis. The endoscopist tried to fragment and remove it, which was not successful.

Figure 1.

Barium Meal Upper GI series showing mottled filling defect with entrapped air in the stomach.

Figure 2.

Axial CECT image shows a nonenhancing mixed density intraluminal gastric mass with foci of air and oral contrast. Mass is circumscribed by oral contrast.

Laparoscopic Removal Technique

The patient underwent laparoscopic-assisted trichobezoar removal from her stomach. She was operated on while in the Lloyd-Davis position with a 300 reverse Trendelenburg tilt. A 6-mm infraumbilical camera port was established for a 5-mm 300 telescope along with 2 more 6-mm ports at the left lumbar region at the level of the umbilicus and 11mm at the right lumbar region. After releasing a few adhesions, a gastrostomy was done over the anterior wall of the stomach by using ultrasonic scissors (Figure 3). The stomach contents were aspirated, and the bezoar mobilized inside the stomach by using the 5-mm suction cannula. The apex of the gastric rent was elevated with a grasper through the left port while the bezoar was mobilized from the fundus holding it with a 10-mm claw forceps (Figure 3). Once the proximal end of the bezoar came out of the stomach, the hard bezoar was again lifted with the claw forceps (Figure 3) to totally remove it from the stomach and insert it into the endobag. The stomach was irrigated, and both ends were examined for any residue. The laparoscope could be inserted through the gastric rent proximally into the fundus of the stomach and distally into the first part of the duodenum through the left lumbar port, which seemed to be a distinct advantage over conventional open surgery. This procedure confirmed the absence of any small residues. The bezoar was removed through a 4-cm upper midline incision in pieces and the anterior gastric wall sutured extracorporeally through it.

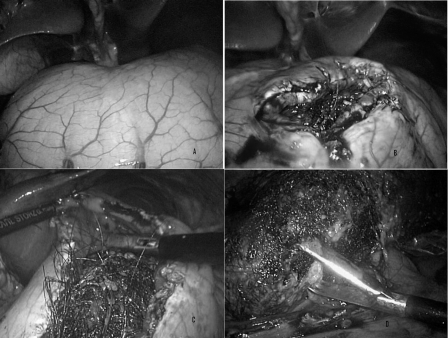

Figure 3.

Intraoperative images: (A) Distended stomach with trichobezoar; (B) Trichobezoar seen inside the stomach after gastrostomy with ultrasonic scissors; (C) Bezoar is mobilized inside the stomach with claw and grasping forceps; (D) Trichobezoar being removed from the stomach with claw forceps before putting into the endobag.

The abdominal retrieval incision was closed and pneumoperitoneum was re-achieved, which allowed us to check the sutured gastric rent and copiously irrigate the right and left subphrenic and paracolic spaces. The patient had a prolonged ileus in her postoperative period, and on her third postoperative day a mild discharge was seen from her main retrieval wound, which subsided within 2 days.

DISCUSSION

Bezoars are classified into 4 main types, according to the materials of which they are composed: Phytobezoars, Trichobezoars, medication bezoars, and lactobezoars. Most common are phytobezoars that consist of indigestible fruits, vegetable fibers, skin, or seeds.2 Phytobezoars are classically found in adults with a history of previous gastric surgery, conditions of reduced gastric acidity, poor gastric mixing, or delayed motility. Trichobezoars, or hairballs, are a mass of hairs, decaying food material or both. Medication bezoars consist of undigested tablets or semi-liquid drugs. Lactobezoars are frequently found in low-birth-weight or premature neonates fed with a highly concentrated formula within the first weeks of life.2

Bezoars usually (90%) are found in children and young females1 with pica, psychiatric disorders, or mental retardation, but rarely a severe psychiatric disorder is seen.3 Usually there are no symptoms until the trichobezoar reaches a substantial size.3 An indentable abdominal mass is the commonest presentation,4 with other features like alopecia circumscripta and signs of gastric outlet obstruction.3 Gastric bezoar formation occurs in patients with altered gastric physiology, impaired gastric emptying, reduced acid production, or all of these together. This is usually caused by previous gastric surgery, such as partial gastrectomy, vagotomy, or pyloroplasty, but may be caused by gastroparesis or gastric outlet obstruction. Contributing factors can include dysmotility of the gastrointestinal tract, dehydration, malnutrition, and diabetes mellitus. After antrectomy, the incidence is as high as 10% to 25%.2 Poor mastication and ingestion of large quantities of indigestible solids may also precipitate bezoar formation.2 Trichobezoar can be associated with Ménétrièr's disease and pancreatitis.3

Ultrasound features are not confirmatory; however, an arc-like surface echo casting a clear posterior acoustic shadow with dilated lumen can suggest the diagnosis.3 Barium can show a cast of the stomach. CECT scan has a high accuracy rate and differentiates it from any neoplasms.4,5 CECT scan shows a well-circumscribed ovoid intraluminal lesion, composed of concentric whorls of different densities with pockets of air enmeshed within it, appearing in the stomach region. Beyond the lesion, the bowel collapses.3 Oral contrast fills the more peripheral interstices of the lesion, and a thin band of contrast circumscribes it. Absence of significant postintravenous contrast enhancement precludes a neoplastic lesion.4 Endoscopy confirms the diagnosis and often the offending bezoar can be removed by this route.3 Trichobezoar has a black color that is seen due to denaturation of proteins and gives a foetid odor due to entrapment of undigested fat in the hair mesh with bacterial colonization.3

Currently accepted treatment of bezoars, include observation, dissolution, fragmentation, and laparotomy and gastrotomy.1 Beyond these other modalities, gastroscopic fragmentation, nasogastric lavage or suction, and enzymatic therapy with cellulose and papain have been tried.6,7 Endoscopy is also known to have a therapeutic potential.4 Endoscopy can be difficult and risky with a few cases of esophageal perforation reported in the literature.3 Endoscopic irrigation with Coca Cola (NaHCO3) can have a mucolytic effect in removing trichobezoars.2 Other minimally invasive modalities like extracorporeal lithotripsy, endoscopic lithotripsy, and laser fragmentation are emerging. Their role, success rates, and complications need to be defined.4,7

Therapeutic laparoscopy is fast emerging and has been demonstrated to be feasible, though difficult in the management of gastric bezoars.1,5–10 Theoretically, 80% of abdominal operations could be performed laparoscopically.1 Laparoscopy is associated with minimal incision, less pain, reduced hospital stay, excellent cosmetic outcome, and fewer complications compared with the open procedure.8,10 Authors have described their techniques with 3 to 5 ports (Table 1). Controversy exits regarding the method of retrieval. Most authors advocate piecemeal removal over in to-to removal. The greatest risk of contamination is at the time of gastrostomy and during its transfer into the endo-bag.9 Disadvantages of laparoscopy could be of longer operating time, higher costs, and problems with retrieval.1,7 Retrieval should always be in an endo-bag and piecemeal, or in to-to removal depends on the size and weight of the bezoar. Impervious endobag is absolutely essential to prevent spillage and infection.

Table 1.

Comparing Various Available Reports of Laparoscopic Gastric Bezoar Removal

| Authors and Year | Technique | Gastrostomy Closure | Retrieval | Size of Bezoar/Time | Recovery | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nirasawa et al 1998 | 4 ports, Gastrostomy with electrocautery | Intracorporeal two layered closure | Direct | 11 cm, 185 g, 300 min | Uncomplicated | Psychiatry OPD follow up |

| Yao et al 2000 | 3 Ports, Anterior longitudinal gastrostomy | Intracorporeal two layers | Surgical gloves, Piecemeal | - | Oral intake POD3, Uneventful recovery | - |

| Shami et al 2007 | Supine, 3 ports, Anterior gastrostomy using ultrasonic scalpel | Intracorporeal Vicryl 2-0 | Endobag, Piecemeal | 17 cm, 720 g, 220 min | Oral intake POD1, Discharge POD3, Wound infection | 1yr, Uneventful |

| Palanivelu et al 2007 | Anterior gastrostomy with stay sutures | Through abdominal retrieval incision | Endobag | - | Oral intake POD3, Discharge POD5 | 2yrs, Uneventful |

| Song et al 2007 | 4 Ports, Anterior gastrostomy, Monopolar cautery | Endo-GIA staplers | Endobag, Piecemeal | 7 cm, -, 50 min | Oral intake POD3, Discharge POD6, Uncomplicated | - |

| Meyer-Rochow et al 2007 | Lloyd Davis position, 5 ports, Gastrostomy with electrocautery | Intracorporeal two layers | Endobag, Piecemeal | 180 min | Oral intake POD2, Discharge POD3, Uneventful | Pregnancy clinic |

| Sharma et al 2010 | Lloyd Davis, 3 ports, Anterior gastrostomy with ultrasonic scissors | Through abdominal retrieval incision | Endobag, Piecemeal | 20 cm, 450 g, 150 min | Oral intake POD5, Discharge POD7, Wound Infection | 21 months, Uneventful. |

Comparisons have been made in small intestinal bezoars with laparoscopy and open surgery8 along with anecdotal reports of single cases.5,11 It can present as an isolated mass or with satellite nodules causing interrupted obstruction.5 The ideal recommended procedure is to milk the bezoar beyond the ileo-cecal valve into the cecum; however, laparoscopic-assisted procedures are also commonly applied. Distention of proximal bowel can hamper visibility, and occasionally locating the intestinal bezoar is difficult in laparoscopy.11

The association of pregnancy merits special mention, as bezoars are commonly seen in young females in the reproductive age group. Laparoscopy during pregnancy is never without the fear of harm, including spontaneous abortion of the developing fetus; however, increasing cumulative worldwide experience suggests that there is no significant difference in fetal morbidity with laparoscopy compared with laparotomy.9

CONCLUSION

The laparoscopic approach to remove gastric bezoars has a better outcome with many benefits over laparotomy and is slowly becoming the treatment of choice. Randomized trials are not possible due to the paucity of cases. Once the underlying disease is dealt with surgically, the cause should be looked into with a multidisciplinary approach to prevent further episodes.

Contributor Information

Deborshi Sharma, Department of Surgery, Lady Hardinge Medical College, New Delhi, India..

Manish Srivastava, Department of Surgery, Lady Hardinge Medical College, New Delhi, India..

Raghavendra Babu, Department of Surgery, Lady Hardinge Medical College, New Delhi, India..

Rama Anand, Department of Radiology, Lady Hardinge Medical College, New Delhi..

Anurag Rohtagi, Department of Radiology, Lady Hardinge Medical College, New Delhi, Division of Medical Endoscopy, Lady Hardinge Medical College, New Delhi, India..

Shaji Thomas, Department of Surgery, Lady Hardinge Medical College, New Delhi, India..

References:

- 1. Nirasawa Y, Mori T, Ito Y, Tanaka H, Seki N, Atomi Y. Laparoscopic removal of a large gastric trichobezoar. J Pediatr Surg. 1998; 33(4): 663–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lin CS, Tung CF, Peng YC, Chow WK, Chang CS, Hu WH. Successful treatment with a combination of endoscopic injection and irrigation with coca cola for gastric bezoar-induced gastric outlet obstruction. J Chin Med Assoc. 2008; 71(1): 49–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O'Sullivan MJ, McGreal G, Walsh JG, Redmond HP. Trichobezoar. J R Soc Med. 2001; 94(2): 68–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rabie ME, Arishi AR, Khan A, Ageely H, Seif El-Nasr GA, Fagihi M. Rapunzel syndrome: the unsuspected culprit. World J Gastroenterol. 2008; 14(7): 1141–1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Palanivelu C, Rangarajan M, Senthilkumar R, Madankumar MV. Trichobezoars in the stomach and ileum and their laparoscopy-assisted removal: a bizarre case. Singapore Med J. 2007; 48(2): e37–e39 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yao CC, Wong HH, Chen CC, Wang CC, Yang CC, Lin CS. Laparoscopic removal of large gastric phytobezoars. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2000; 10(4): 243–245 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shami SB, Jararaa AA, Hamade A, Ammori BJ. Laparoscopic removal of a huge gastric trichobezoar in a patient with trichotillomania. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2007; 17(3): 197–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yau KK, Siu WT, Law BK, Cheung HY, Ha JP, Li MK. Laparoscopic approach compared with conventional open approach for bezoar-induced small-bowel obstruction. Arch Surg. 2005; 140(10): 972–975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Meyer-Rochow GY, Grunewald B. Laparoscopic removal of a gastric trichobezoar in a pregnant woman. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2007; 17(2): 129–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Song KY, Choi BJ, Kim SN, Park CH. Laparoscopic removal of gastric bezoar. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2007 Feb; 17(1): 42–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kan JY, Huang TJ, Heish JS. Laparoscopy assisted management of jejunal bezoar obstruction. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2005. September; 15(5): 297–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]