This report describes a case of gallstone ileus managed with a totally laparoscopic approach.

Keywords: Gallstone ileus, Laparoscopic enterolithotomy, Small bowel obstruction, Laparoscopy

Abstract

Gallstone ileus is a well-recognized clinical entity. It usually affects elderly female patients, and very often diagnosis can be delayed resulting in high morbidity and mortality. An abdominal x-ray and computed tomographic (CT) scan of the abdomen may show classical radiological features of small bowel obstruction, pneumobilia, and an ectopic gallstone. Laparotomy and enterlithotomy with or without definite biliary surgery is an established treatment. Since 1992, many cases of laparoscopic-assisted enterolithotomy have been reported. Only a few cases of a totally laparoscopic approach have been documented. We present the case of a 75-year-old lady who presented with features of intestinal obstruction. A plain x-ray of the abdomen and a CT scan confirmed the classical features of gallstone ileus. A totally laparoscopic enterolithotomy was performed using 6 ports. A 6-cm gallstone was retrieved through a longitudinal enterotomy. The transverse closure of the enterotomy was performed with intracorporeal suturing, resulting in an uneventful postoperative recovery. We suggest that a CT scan helps in the early diagnosis of the cause of intestinal obstruction, and totally laparoscopic enterolithomy with intracorporeal enterotomy repair is a valid, safe option.

INTRODUCTION

Gallstone ileus is a well-recognized clinical condition. For many decades, it has affected 30 to 35 patients per 1 000 000 hospital admissions. The common incidence is at age 65 years to 75 years with a female preponderance.1 Mortality remains quite high ranging from 12% to 72%, and morbidity is between 11% and 25%.(ref) The traditional treatment is laparotomy and enterolithomy with or without a definitive biliary procedure. The use of a CT scan for the diagnosis of small bowel obstruction has been increasing. Minimally invasive surgery for the treatment of gallstone ileus has been evolving; now more management options are available to high-risk patients.2,3

CASE REPORT

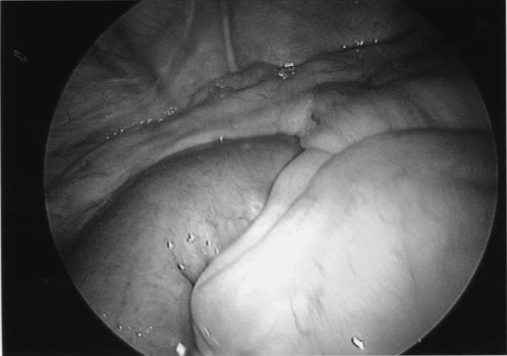

A 75-year-old lady was admitted with a 6-day history of intermittent central abdominal pain associated with vomiting. She was previously fit and healthy with no history of any abdominal operations in the past. Her ASA score was 2. On clinical examination, she has mildly dehydrated. Her abdomen was soft but not tender and only showed slight fullness. She had no scar or evidence of an external hernia. Her hemoglobin and WBC count were normal. Plain x-ray of the abdomen showed pneumobilia and dilated loops of small bowel (Figure 1). A CT scan of the abdomen showed an ectopic gallstone causing a transition point of collapse and dilated loops of small bowel. She did not improve on conservative management of intravenous fluid and nasogastric aspiration; therefore, with the patient under general anesthesia, a laparoscopy was performed using a 0-degree, 10-mm laparoscope through a peri-umbilical port with the open technique. Two 5-mm ports were used on either side to manipulate the small bowel. A bulge in the small bowel was seen due to a stone, resulting in proximal dilated small bowel and collapse of distal loops (Figure 2). Two atraumatic forceps were used to occlude the lumen proximal and distal to the site of obstruction. The atraumatic forceps were applied after milking the intestinal content proximally. Additional 5-mm and 10-mm ports were used for dissection. A 5-cm longitudinal enterotomy was made 10cm proximal to the site of obstruction, using diathermy. Minimal contamination was noticed (Figure 3). The stone was retrieved in an Endocatch retrieval bag through the 10-mm port site at the end of the procedure. Transverse closure of the enterotomy was performed using PDS 2-0, in 2 layers (Figure 4). The patient had an uneventful recovery, and her bowel became fully functional on the third postoperative day. However, she was discharged on the 11th postoperative day due to her social circumstances. She received 3 doses of antibiotics, one dose pre- and 2 doses postoperatively.

Figure 1.

A stone in dilated small bowel and collapsed small bowel.

Figure 2.

Stone coming out through the enterotomy.

Figure 3.

Intracorporeal transverse repair of the enterotomy.

Figure 4.

A 6-cm stone coming out of the enterotomy.

Figure 5.

Air in billiary tract.

Figure 6.

Dilated small bowel loops with large gallstone.

Figure 7.

Air in common bile duct and gallstone in distal small bowel.

DISCUSSION

The term gallstone ileus is technically a misnomer, because it is a true mechanical obstruction caused by a stone passed through a cholecysto-enteric fistula and impacting the intestine causing obstruction to the flow of intestinal contents. A preoperative diagnosis is frequently delayed. Use of a CT scan to diagnose the cause of small bowel obstruction is gaining more acceptance, and gallstone ileus is a classical example to achieve an accurate diagnosis. The 3 radiological features of aerobilia, ectopic gallstone, and dilated small bowel as described by Riglers et al4 in 1941 were demonstrated on CT scan in our case. It helps in planning further management. Enterolithotomy alone and enterolithotomy combined with definitive biliary tract surgery and fistula closure both have been proven to be safe procedures by a traditional open surgical approach.5,6 Though the former procedure has been reported as being safer in high-risk patients, it is technically less demanding and requires a shorter operating time.

With increasing experience in laparoscopic bowel surgery, a few authors have reported their experiences with laparoscopic-assisted enterolithotomy,7,8 which minimizes the surgical trauma to patients and results in quicker recovery. Laparoscopy also helps in the diagnosis. Extra care is always required to achieve pneumoperitoneum and optical port insertion, as dilated bowel is at high risk of injury. Open cannulation for the primary port insertion is highly recommended.

By using a laparoscopic approach, the impacted gallstone in the ileum can be moved and pushed into the large bowel where spontaneous passage through a natural orifice has been reported. This can result in inadvertent small bowel injury and uncontrolled peritoneal contamination.9

The nondistended small bowel along with the impacted stone can be exteriorized through a separate incision. Stones can be removed externally after a longitudinal enterotomy and transverse closure.

The whole procedure can be completed totally laparoscopically. There is a risk of spillage of small bowel contents into the peritoneal cavity however. Some surgeons have used nylon tape at the proximal dilated bowel to achieve control.10 This is a useful technique, though it can potentially result in mesenteric injury and bleeding from engorged mesenteric blood vessels. In our case, we managed to achieve control of small bowel on both sides of the stone with atraumatic forceps, a laparoscopic replication of the technique traditionally used in open surgery.

CONCLUSION

Definitive treatment of a biliary fistula is not always required. The choice of surgical procedure is usually dictated by the clinical condition of the patient. We think that the safer option in high-risk patients is to perform enterolithomy alone. The mainstay of the treatment in these elderly patients is to relieve the bowel obstruction. The whole procedure can be performed laparoscopically and is a valid and safe option to offer to high-risk patients.

Contributor Information

Muhammad Hanif Shiwani, Barnsley General Hospital National Health Service Foundation Trust, Barnsley, United Kingdom..

Quat Ullah, Barnsley General Hospital National Health Service Foundation Trust, Barnsley, United Kingdom..

References:

- 1. Reisner RM, Cohen JR. Gallstone ileus: a review of 1001 reported cases. Am Surg. 1994;60:441–446 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Patel VG, Gonzales JJ, Fortson JK, Weaver WL. Laparoscopic management of gallstone ileus. Am Surg. 2009;75(1):84–86 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. El-Dhuwaib Y, Ammori BJ. Staged and complete laparoscopic management of cholelithiasis in a patient with gallstone ileus and bile duct calculi. Surg Endosc. 2003;17(6):988–989;Epub 2003 Mar 14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rigler LG, Borman CN, Noble JF. Gallstone obstruction. Pathogenesis and roentgen manifestations. JAMA. 1941;117:1753–1759 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tan YM, Wong WK, Ooi LLPJ. A comparison of two surgical strategies for the emergency treatment of gallstone ileus. Singapore Med J. 2004;45:69–72 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Riaz N, Khan MR, Tayeb M. Gallstone ileus: retrospective review of a single centre's experience using two surgical procedures. Singapore Med J. 2008;49(8):624–626 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sarli L, Pietra N, Costi, Gobbi S. Gallstone Ileus: Laparoscopic-assisted enterolithotomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;186(3):370–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moberg AC, Montgomery A. Laparoscopically assisted or open enterolithotomy for gallstone ileus. Br J Surg. 2007;94(1):53–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Soto DJ, Evan SJ, Kavic MS. Laparoscopic management of gallstone ileus. JSLS. 2001;5:279–285 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Owera A, Low J, Ammori BJ. Laparoscopic enterolithotomy for gallstone ileus. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2008;18(5):450–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]