This study describes a case of urinary bladder pheochromocytoma that presented with paraneoplastic manifestation of bowel symptoms and thrombocytosis managed with laparoscopic techniques.

Keywords: Robotics, Bladder pheochromocytoma

Abstract

Pheochromocytoma of the urinary bladder is rare, presenting usually with hypertension, hematuria and syncopal attacks. Such cases have usually been managed with open or laparoscopic partial cystectomy. We present a case of bladder pheochromocytoma that had unusual presenting symptoms, a paraneoplastic manifestation and was successfully managed with robotic technique.

INTRODUCTION

Pheochromocytoma is a neoplasm of chromaffin tissue of sympathetic nervous system mostly arising from the adrenal medulla. Extra-adrenal pheochromocytomas, also called paragangliomas are uncommon. Bladder pheochromocytomas are extremely rare and mostly present with paroxysms of hypertension, syncopal attacks or hematuria.1 We report a case of large urinary bladder/ureter pheochromocytoma that had unusual presentation with bowel symptoms and thrombocytosis as paraneoplastic manifestation. The case was successfully managed robotically with partial cystectomy, distal ureterectomy and ureteric reimplantation. After thorough medline search, this seems to be the first such robotically managed case of vesicoureteric junction pheochromocytoma.

CASE REPORT

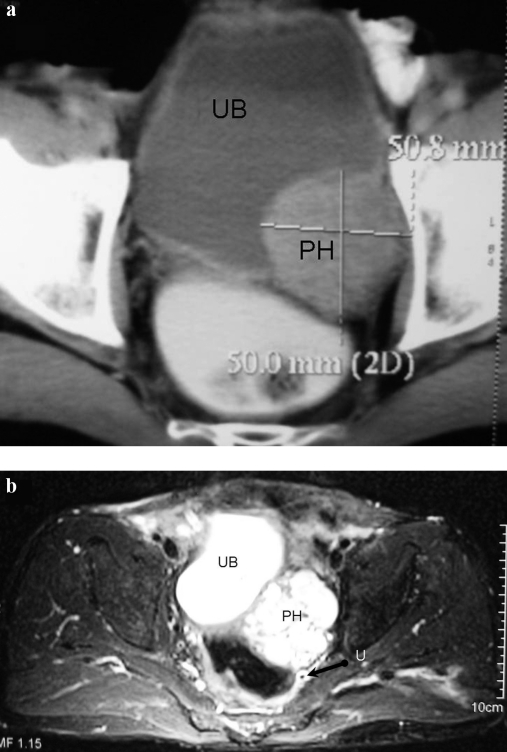

A 59 years/male presented with constipation, tenesmus and sense of incomplete evacuation for one year, alongwith mild hypertension for four months easily controlled on medication. There was no episodic hypertension, syncope, hematuria or lower urinary tract symptoms. Family history was insignificant and there were no contributory per-rectal or systemic examination findings. Patient was also evaluated earlier in gastroenterology clinic. Stool for occult blood and colonoscopy were normal. Ultrasound abdomen showed 5.1 × 4.8 cm echogenic mass posterior to urinary bladder, indenting its wall and causing left hydro-ureteronephrosis. CECT (Figure 1a) revealed the mass, along left side of bladder wall, involving left vesicoureteric junction with proximal hydroureteronephrosis. Bulk of the mass was lying in the space between the bladder anteriorly and ureter posteriorly. Serial urinary cytology samples were negative for malignancy. A bladder tumor of subepithelial tissue origin, likely a leiomyoma was suspected. A cystoscopic examination demonstrated intact mucosa with a large mass projecting into bladder over left side of base and elevating the left ureteric orifice. Left JJ-stenting and TUR biopsy was done during which an unexpected paroxysm of sympathetic activation was encountered and the blood pressure of patient increased up to 250/160 mm Hg along with severe tachycardia. Procedure was therefore abandoned with suspicion of urinary bladder pheochromocytoma. Functional evaluation confirmed presence of pheochromocytoma with raised 24 hr urinary metanephrines-189.58 μg/creatinine (<155) and normetanephrines-6960.46 μg/creatinine (<256). MRI and MIBG scan were done to rule out other sites of pheochromocytoma. MRI (Figure 1b) confirmed pheochromocytoma with characteristic ‘flash bulb’ appearance of mass on T2 weighted images. Biopsy report of the few resected tissue chips also confirmed the diagnosis. During further evaluation patient was found to have thrombocytosis with platelet counts of >1000 million/mm3. After thorough hematologic investigations, no specific etiology for thrombocytosis could be ascertained and it was considered to be paraneoplastic. Patient was started on an alpha blocker followed by beta blockers for two weeks. Hematocrit was optimized with hydration in preparation for elective surgery and low molecular weight heparin was prescribed starting one day prior to surgery.

Figure 1.

(a) CECT, and (b) MRI films demonstrating a mass (PH) involving the urinary bladder (UB), left ureter (U) and vesicoureteric junction with hydroureteronephrosis. The mass was subsequently confirmed to be a pheochromocytoma. A JJ stent can be seen in situ (arrow).

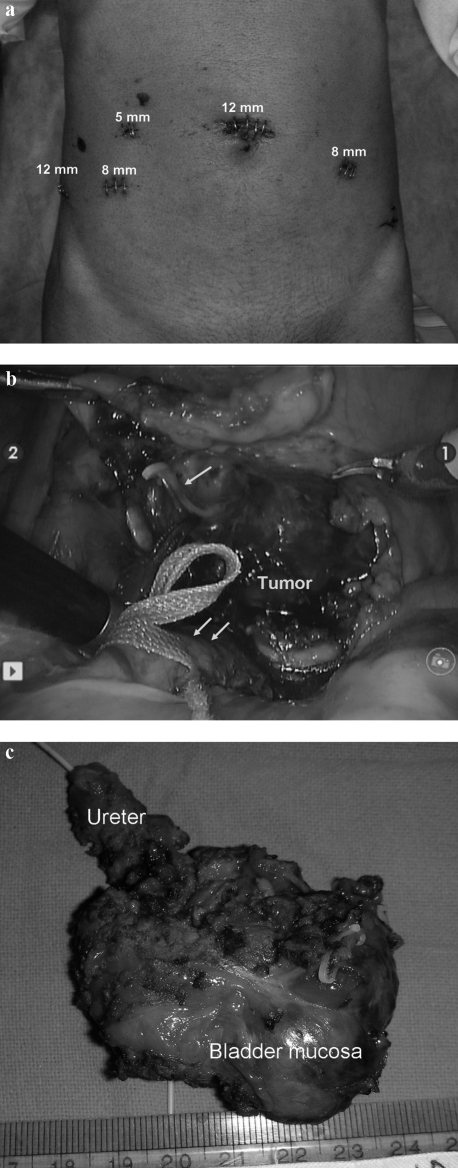

Cystoscopy was done first and margins of resection were defined using deep incisions with a Collins knife. Ports were placed and patient position was then changed to steep trendlenberg. Transperitoneal robotic partial cystectomy, left distal ureterectomy and ureteric reimplantation was done using da Vinci-S robotic surgical system (Figure 2). Dissection was done with efforts to minimize tumor handling. Peritumor vessels were identified and ligated. The ureter was reimplanted using 3′0 polyglecaprone interrupted sutures, in refluxing fashion. A non-refluxing anastomosis was not considered essential given the male gender and elderly age of the patient. The residual bladder opening was closed using 2′0 polyglecaprone continuous interlocking sutures in one layer. Intaoperative blood pressure fluctuations were controlled with intravenous fluids, sodium nitroprusside and nitroglycerine drip. Blood pressure stabilized immediately after complete resection of tumor. Umbilical port was used for retrieval of the specimen in endocatch bag. Blood loss was less than 50 cc. A pelvic drain was kept for two days. Patient was discharged on third postoperative day and urethral catheter removed after two weeks. Histopathology confirmed the lesion to be pheochromocytoma arising from urinary bladder and ureter. All resected margins were free of tumor. Platelet count came to normal levels by third day of surgery. At 3 months follow up patient remains normotensive with normal MIBG scan and normal drainage on intravenous urogram. The bowel symptoms of the patient have also disappeared.

Figure 2.

(a) Port position. (b) Intraoperative photograph showing relation of tumor with left ureter (double arrow) and urinary bladder. A draining vein is being clipped (arrow). (c) Resected specimen.

DISCUSSION

Urinary bladder pheochromocytomas account for less than 0.1% of all bladder tumors and less than 1% of all pheochromocytomas2 seen mostly in young adults. They arise from paraganglionic cells within the bladder wall, usually in area of trigone.3 Most of these tumors are functionally active and cause paroxysms of hypertension or syncope,4 typically seen on filling and/or emptying of bladder in two thirds of patients. Hematuria may be present in 50% of cases. Our case was unique on three accounts (1) Having elderly age and none of the usual presenting symptoms. His complaints pertained only to bowel involvement which may be assumed to be related to proximity of the tumor with the rectum (2) Presence of thrombocytosis, as a paraneoplastic feature, and (3) Robotic resection of the tumor with ureteric reimplantation, a first of its kind in medical literature.

Paraneoplastic manifestations have earlier been reported in pheochromocytoma5–7 though they are uncommonly seen in benign tumors. Present case had thrombocytosis as a paraneoplastic manifestation and long term follow up still remains to be seen, however the histopathology did not show any overt malignant features. The thrombocytosis was not related to hemoconcentration and persisted even after adequate hydration was done and hematocrit declined to 32. It being a paraneoplastic manifestation is further confirmed by the platelet count coming to normal after removal of the tumor.

Though several newer diagnostic modalities have been developed to diagnose extraadrenal pheochromocytoma,8 it is still nearly impossible to diagnose early in patients presenting asymptomatically. For urinary bladder pheochromocytoma, a high index of suspicion is essential to diagnose the case and avoid inadvertent cardiovascular event during transurethral resection of the tumor. Any such case should be well hydrated and blood pressure well controlled with alpha and beta blockers before surgical resection is contemplated in any form. The diagnosis was initially missed in our case due to his uncommon symptomatology. He had only bowel symptoms and mild hypertension which had its onset at an elderly age and was controlled easily on a single medication. However, the occurrence of episodic hypertension and tachycardia during cystoscopy clinched the diagnosis, and procedure was discontinued till further work up was done. Continuing with transurethral resection is generally contraindicated in pheochromocytoma, because (a) it may precipitate hypertensive crisis by irrigating the tumor (b) recurrence is common if resection is incomplete, and (c) higher chances of malignancy by 30% in extra-adrenal pheochromocytoma than that of adrenal pheochromocytoma. Partial cystectomy with concomitant excision of tumor is therefore considered as the treatment of choice.

While open or laparoscopic partial cystectomy for urinary bladder pheochromocytoma have been reported,9–11,1 to our knowledge there are no such reports for the robotic technique. We made deep incisions around the involved bladder wall during cystoscopy to ascertain resection margins and also to save opposite ureteric orifice. Though an initial attempt to save the ureter was made during robotic surgery, the realization of ureter being involved by tumor led us to add distal ureterectomy to partial cystectomy. Reconstruction was done by closing the bladder defect and ureteric reimplantation using Lich-Gregoir technique. The advantages to be gained by doing the surgery robotically are minimal blood loss and perioperative morbidity; short convalescence and hospital stay; ease and precision of dissection and reconstruction; and cosmesis. All of these were apparent in our case.

Contributor Information

Rishi Nayyar, Department of Urology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India..

Prabhjot Singh, Department of Urology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India..

Narmada P Gupta, Department of Urology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India..

References:

- 1. Liu Y, Dong S, Dong Z, Mao X, Shi X. Diagnosis and treatment of pheochromocytoma in urinary bladder. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2007;8(6):435–438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Albores-Saavedra J, Maldonado ME, Ibarra J, et al. Pheochromocytoma of the urinary bladder. Cancer. 1969;23:1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Koss LG. Tumors of the urinary bladder. In: Atlas of Tumor Pathology. Vol 16, 2nd Series Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1975;1 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Onishi T, Sakata Y, Yonemura S, Suqimura Y. Pheochromocytoma of urinary bladder without typical symptoms. Int J Urol. 2003;10(7):398–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bazhenova L, Du EZ, Bhoyrul S, McCallum J, Saven A. Reactive thrombocytosis associated with a pheochromocytoma. Thromb Haemost. 2005;94(2):460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Petidis K, Douma S, Doumas M, et al. Pheochromocytoma: “The Great Mimic”: Thrombosis of portal vein and splenic vessels as first presentation of pheochromocytoma. Endocrinologist. 2008;18(3):121–123 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fukumoto S, Matsumoto T, Harada S, et al. Pheochromocytoma with pyrexia and marked inflammatory signs: a paraneoplastic syndrome with possible relation to interleukin-6 production. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1991;73(4):877–881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Karpman E, Zvara P, Stoppacher R, Jackson TL. Pheochromocytoma of urinary bladder: update on new diagnostic modalities plus case report. Ann Urol. 2000;34:113–119 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Baima C, Casetta G, Vella R, Tizzani A. Bladder pheochromocytoma: a 3-year follow-up after transurethral resection (TURB). Urol Int. 2000;65(3):176–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Naqiyah I, Dohaizak M, Meah FA, Nazri MJ, Sundra M, Amram AR. Pheochromocytoma of the urinary bladder. Singapore Med J. 2005;46(7):344–346 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Safwat AS, Bissada NK. Pheochromocytoma of the urinary bladder. Can J Urol. 2007;14(6):3757–3760 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]