Abstract

A randomized trial tested the efficacy of three curriculum versions teaching drug resistance strategies, one modeled on Mexican American culture; another modeled on European American and African American culture; and a multicultural version. Self-report data at baseline and 14 months post-intervention were obtained from 3, 402 Mexican heritage students in 35 Arizona middle schools, including 11 control sites. Tests for intervention effects used simultaneous regression models, multiple imputation of missing data, and adjustments for random effects. Compared with controls, students in the Latino version reported less overall substance use and marijuana use, stronger intentions to refuse substances, greater confidence they could do so, and lower estimates of substance-using peers. Students in the multicultural version reported less alcohol, marijuana, and overall substance use. Although program effects were confined to the Latino and multicultural versions, tests of their relative efficacy compared with the non-Latino version found no significant differences. Implications for evidence-based practice and prevention program designs are discussed, including the role of school social workers in culturally grounded prevention.

Keywords: adolescents, evidence-based intervention, longitudinal study, Latinos, middle school, substance use prevention programs

School social workers are increasingly called on to advise and participate in decision making regarding the selection and implementation of prevention curriculums that address the challenge of youth substance use. Funding sources at the federal, state, county, and municipal levels require that prevention curriculums be selected from approved evidence-based lists such as the model-programs list sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMSHA) (2003). Social workers can play a critical role in these decisions, raising issues such as cultural relevance, resilience versus risk perspectives, and consideration of the cultural and social settings of the school community. When program lists do not provide the type needed for a particular school context, designing and testing innovative models is a natural alternative. This article describes the process of designing and testing a culturally grounded prevention model created by social work researchers, their partners from other disciplines, teachers, students, and parents.

The challenge of preventing youth substance use is a national priority. Before leveling off at high levels and dipping slightly in the past few years, rates of youth substance use climbed sharply during the 1990s despite the widespread proliferation of stand-alone, integrated, and “blueprint” prevention and intervention programs at multiple levels of the U.S. education system (Johnston, O’Malley, & Bachman, 2000). A growing concern is the large spurt of initiation in substance use that occurs from seventh to 10th grade, because these youths are at higher risk of substance abuse later (National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse, 1994, 2002). Because of cultural differences and socioeconomic disparities, ethnic and racial factors play a role in this crucial period of initiation into substance use. For the U.S. population as a whole, the substance use rates of Latinos fall in between the lower rates for African Americans and the higher rates for non-Latino white individuals. However, in some regions of the country and for certain substances, rates of use are highest for Latino youths (Johnston et al.; Marsiglia, Kulis, & Hecht, 2001). Moreover, because of their much higher school dropout rate, substance use rates for Latino youths are probably substantially underestimated in major school-based surveys (Johnston et al.). The differential rate of adolescent substance use among various ethnic groups is an important issue requiring additional prevention research.

CULTURE AND PREVENTION

Research findings suggest that culture is a relevant factor in substance use and its prevention and that models for adolescents should reflect the learning styles and culture of the population in the design of the program’s content and format (Castro, Proescholdbell, Abeita, & Rodriguez, 1999; Kandel, 1995). When ethnic minority students recognize themselves in the program content, such as when their teachers or the program models are members of their ethnic group, they appear to relate more readily to the embedded messages and act to support them (Dorr, 1982; Eigen & Siegel, 1991). Although researchers have given more attention to racial or ethnic group differences during the development and evaluation of many substance use prevention programs, they have developed few programs for Mexican American youths (Polansky, Buki, Hran, Ceperich, & Burows, 1999). It is unclear whether prevention messages crafted for predominantly middle-class white populations are equally effective for Latinos.

Research on culturally oriented prevention messages are at an early stage of development. Although they have generally been shown to be effective, the research has many limitations: small-scale findings (Botvin, Griffin, Diaz, & Ifill-Williams, 2001), majority-dominated school populations (Ellickson & Bell, 1990), and samples composed of multiple racial or ethnic minority groups rather than a single cultural group (Botvin et al., 1997; Botvin, Griffin, Diaz, & Ifill, 2001). Moreover, efforts to date have relied on modifications of programs designed for the majority culture rather than prevention strategies grounded in the culture of the ethnic minority group. To address some of these issues, we assessed the relative efficacy of three culturally grounded versions of the keepin’ it REAL drug resistance program in a large-scale, randomized trial conducted with Mexican and Mexican American middle school students.

KEEPIN’ IT REAL

keepin’ it REAL is a school-based adolescent substance use intervention program designed to test the effectiveness of culturally grounded prevention messages and the importance of their match to the ethnicity of program participants. Using an ecological risk and resilience approach (Bogenschneider, 1996), the intervention was developed in a narrative and performance framework (Fisher, 1987) to enhance cultural identification, to promote personal antidrug norms and behaviors (Cialdini, Reno, & Kallgren, 1990; Hansen, 1991), and to develop decision-making and resistance skills (Bandura, 1977). The intervention stresses the cultural norms of the targeted group by integrating values identified as most salient for success in communicating with youths from that group (Hecht & Ribeau, 1984; Hecht, Ribeau, & Alberts, 1989; Rodriguez, 2001). With cultural specificity at the core of the curriculum, the intervention focuses on five key elements of adolescent life: communication competence, narrative knowledge, motivating norms, social learning, and resistance skills.

Relying on research (Hecht & Ribeau, 1984; Hecht et al., 1989; Hecht, Ribeau, & Sedano, 1990; Kochman, 1981) that illustrated ethnic differences in common communication styles, competencies, and norms, the intervention demonstrates how youths could resist offers of substance use without violating the social structures cherished by their culture (Marsiglia & Holleran, 2000). A central component of the intervention is a 10-lesson curriculum with direct instruction, in-class participatory exercises, enhanced video illustrations, and homework assignments (for details on curriculum development see Gosin, Marsiglia, & Hecht, 2003). Five of the lessons were video-based. All the components teach cognitive skills, appropriate behaviors, and communication skills for successful use of four “REAL” resistance strategies: refuse, explain, avoid, and leave.

Curriculum and video content were developed from ethnographic data collected at local middle schools, a process that identified the situational contexts of drug offers and culturally appropriate ways that students resisted them. Students from a local communication arts magnet high school were integrally involved in the videos’ development, production, and acting. The videos showed clearly that they were made for and by local youths and situated the depictions of drug resistance strategies in recognizable social and physical environments (for details of video development see Holleran, Dustman, Reeves, & Marsiglia, 2002). To accommodate the substantial minority of native Spanish-speaking students, teachers used English and Spanish materials in each version of the curriculum.

Three versions of the curriculum were created: (1) a Latino version, primarily reflecting Mexican American and Mexican values; (2) a version grounded in European American and African American values; and (3) a multicultural version created by taking half the lessons from the Latino version and half the lessons from the non-Latino version, and alternating them in presentation. The curriculum versions were field-tested for instructional validity and age and language appropriateness with groups of students and teachers, using school venues that matched those of the intervention design. Because they constituted less than 5 percent of the study population, logistical and funding constraints made it impractical to achieve the required level of power to test the efficacy of a culturally grounded version of the curriculum targeting African Americans.

The curriculum and videos were supplemented by a public service announcement (TV and radio) and billboard campaign and a follow-up year of booster activities conducted approximately every month at the intervention schools. The boosters encompassed such activities as eighth-grade school assemblies, poster projects, murals, neighborhood nights out, and essay contests. Teachers received a full day of training and two half-day follow-up sessions covering the implementation of school booster activities and program evaluation (Harthun, Drapeau, Dustman, & Marsiglia, 2002). Teachers could refer students needing psychosocial support to school-based, social-work facilitated, student support groups.

The intervention was tested in Phoenix, Arizona, a city whose Latino population—overwhelmingly of Mexican background—more than doubled from 1990 to 2000, to more than one-third of all residents and a majority of students enrolled in city schools. Our hypotheses proceed from a core assumption that the students’ recognition of their culture in the content of the intervention would result in greater program effectiveness. We hypothesized that all three versions of the intervention would be more effective compared with controls in delaying or reducing substance use and in promoting antidrug attitudes and norms among Mexican American or Mexican youths; that the culturally grounded Latino version of the school-based intervention would be the most effective; that the non-Latino version would be the least effective; and that the multicultural version would be intermediate in effectiveness. The rationale for the last hypothesis was that Although a minority proportion of the youths would be sheltered in a recent-immigrant Mexican cultural environment, most would be navigating an acculturation process that requires daily contact with non-Latino cultural environments and institutions.

METHOD

Research Design

The present study used a pre–post experimental design with three intervention conditions and one control or comparison condition. Self-report data were collected on two occasions from students enrolled in 35 public middle schools in the central corridor of the Phoenix metropolitan area. Schools were stratified according to size of enrollment and ethnicity (that is, percent of Latino students) and then assigned by block randomization to one of four conditions—Latino, non-Latino, multicultural, or control—with eight to 10 schools in each condition. In the fall semester of 1998, all seventh graders in the study schools were administered a baseline, or pretest, questionnaire. In the spring semester of 1999, their regular seventh-grade classroom teachers delivered the assigned intervention to intervention students; and during the summer, a bilingual radio and television public service announcement and billboard campaign was fielded. During the following school year (1999—2000), the intervention schools implemented school-based booster activities with their eighth-grade students. Finally, in spring 2000, approximately 14 months after completion of the classroom curriculum, a posttest questionnaire was administered to all eighth-grade students who were then enrolled in the 35 study schools, including some students who had not completed the pretest. During the period between the pretest and posttest, students in the control condition participated in the existing substance use prevention programs chosen by their school or school district personnel to meet state mandates for prevention programming (see Hecht et al., 2003, for more detailed information).

Participants

The reported findings are based on data from 3,402 students in the study schools during the 1998–1999 school year who reported their race or ethnicity as Mexican American, Mexican, or Chicano and completed the pretest or the posttest questionnaires or both. Among these students, 63 percent claimed an exclusively Mexican heritage, and the remaining 37 percent identified with other ethnic groups in addition to their Mexican heritage. Most typically the other claimed identities were white or American Indian, identities that are consistent with a “mestizo” identity, an amalgamation of Spanish and indigenous heritage that is considered distinctively Mexican (Vasconcelos, 1926). Given this observation and that, in general, separate analyses of the intervention’s effectiveness with and without the multiethnic Mexican respondents showed few differences, we report findings based on the larger sample of students claiming some Mexican heritage, except where noted.

Questionnaires

The questionnaires (each up to 82 items) were a three-form design (Graham, Hofer, & MacKinon, 1996; Graham, Hofer, & Piccinin, 1994; Graham, Taylor, & Cumsille, 2001) using planned missingness to limit the number of items each student received in his or her questionnaire, while maximizing the total number of items included for analysis. Project-trained proctors rather than teachers administered the 45-minute questionnaires, which were written in English on one side and in Spanish on the other side. Questionnaires were completed during regular school hours, typically in science, health, or homeroom classes. Students were given written and verbal guarantees of confidentiality and told that their participation was voluntary.

Measures

Demographic Characteristics

The students indicated their ethnic/racial background through six yes or no items that asked if they were: (a) Mexican American, Mexican, Chicano/a; (b) other Latino (Puerto Rican, Cuban, and so forth.); (c) white (Anglo); (d) African American (black); (e) American Indian (Pima, Yaqui, Navajo, and so forth); or (f) Asian or Pacific Islander (Chinese, Japanese, and so forth). This scheme allowed students to report mixed ethnic backgrounds. The present analysis is restricted to students who marked yes to the first item at baseline or posttest. Students reported their gender by marking male or female, age by indicating their birth date, and their school lunch participation by choosing free lunch, reduced-price lunch, or neither.

Substance Use Outcomes

The questionnaires included self-reports of how much and how frequently students drank alcohol, smoked cigarettes, and smoked marijuana in the past 30 days. Although not perfectly correlated, up to 95 percent agreement has been reported between saliva samples and drug use self-reports (Ellickson & Bell, 1990). Evidence in support of valid self-report data is especially strong in analyses of reports on drug use activities during the past 30 days (Graham, Flay, & Johnson, 1984; Johnston, 1989; O’Malley, Bachman, & Johnston, 1983), and in comparisons of self-reports over time and across treatments (Smith-Donals & Klitzner, 1985). The drug-use items were modeled after Likert scales used by Flannery and colleagues (1994) with a population of similar ages. To assess the amount, students indicated number of drinks (1 = none to 9 = more than 30), cigarettes (1 = none to 8 = more than two packs), and hits of marijuana (1 = none to 8 = more than 40). Frequency of each type of substance use was measured in terms of the number of days of use in the past month (1 = none to 6 = 16 to 30). The responses on amount and frequency were averaged separately for each substance and together across substances to obtain a measure of overall recent substance use; this demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = .86).

Refusal Confidence

This three-item measure assessed students’ confidence (1 = not at all sure to 5 = very sure) in saying no to alcohol, tobacco, and other drug offers from “a friend (they) really liked.” “someone (they) don’t know well,” or “a family member (parents, brothers, sisters, aunts, uncles, etc.).” The measure was based on Kasen and colleagues’ (1992) self-efficacy scale and was formed by averaging the three item scores; larger scores indicated greater confidence in ability to refuse drug offers. Internal consistency (α) was .74.

Intention to Accept Substance Offers

This measure assessed intention to accept offers of “alcohol to drink (beer, wine, hard liquor),” “a cigarette,” or “marijuana” (l = definitely no to 4 = definitely yes). The intention score was formed by averaging the three item scores; larger scores indicated stronger intention to use substances. Internal consistency (α) was .81.

Positive Substance-Use Expectancies

This six-item measure assessed students’ perceptions of the positive consequences of substance use. Three alcohol items (Hansen & Graham, 1991) asked if drinking alcohol makes it easier “to be part of a group,” “to have a good time with friends,” or “makes parties more fun.” Two cigarette items asked if “smoking cigarettes makes people less nervous” and if smoking makes “it easier to concentrate.” One item asked if marijuana makes “food taste better.” The response choices for all six items (1 = never to 5 = most of the time) were averaged; larger scores indicated more positive substance use expectancies. Internal consistency (α) was .74.

Personal, Injunctive, and Descriptive Norms

The Focus Theory of Norms (Cialdini et al., 1990) was used to identify and measure three types of norms: personal (what the individual thinks is right or wrong), injunctive (what the individual believes that others think is right or wrong), and descriptive (how many of an individual’s peers use drugs). The questionnaires assessed antidrug personal norms by asking: “Is it OK for someone your age to…” “drink alcohol,” “smoke cigarettes,” or “use marijuana.” The questions were based on those used by Hansen and Graham (1991). Possible responses ranged from 1 = definitely OK to 4 = definitely not OK. The three item personal norms measure demonstrated high internal consistency (α = .86). The items related to antidrug injunctive norms focused on parents and best friends and were based on those used by Hansen and Graham and Hansen and colleagues (1988). The items asked how angry students’ parents would be if they found out that the student “smoked marijuana,” “smoked cigarettes,” or “drank alcohol” (three individual items scaled 1 = not angry at all to 4 = very angry), and how their best friends would react if they engaged in these behaviors (three additional items on scales of 1 = very friendly to 4 = very unfriendly). Internal consistency was .71 and .81, respectively for the parent injunctive norms and friend injunctive norms measures. Last, two descriptive norms items asked the respondents to estimate how many students in their schools tried alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs at least once, and how many students in their schools use drugs regularly (both on reversed scales of 1 = hardly any to 4 = most; α = .72).

Variables Used Only for Missing Data Imputation

Multiple imputation was used to handle missing data. The imputation model included measures of current grades (1 = mostly Fs to 9 = mostly As), how far the students expected to get in school (1 = finish 8th grade to 5 = finish four years of college), language chosen to complete the follow-up questionnaire (English or Spanish), and language used with parents and friends (separate items coded 1 = Spanish only to 5 = English only). The model also included six items assessing strength of ethnic identification: two regarding the students’ culturally relevant behaviors and speech, two tapping their sense of belonging to or feeling good about their race or culture, and two measuring negative feelings toward their ethnic heritage (embarrassment or criticism of the way youths who are co-ethnic talk and act). All ethnic identity items were scaled from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree.

Statistical Analyses

The analyses were complicated by record-linking difficulties. Because most principals objected to the use of name-linked, unique student identifiers (usually based on human subjects policies), the student’s school, gender, initials (first and last names), and date of birth were used to create an identifier. Using the latter, we were able to link the pretest and posttest questionnaires of 51 percent of the 3,402 students, with another 35 percent providing information only at baseline, and 14 percent providing information only at the follow-up. We were unable to link the records of 182 students who received the Latino version because they were attending two schools that dropped out in the study’s second year. In an additional 2 percent of the unlinked cases, students did not accurately or completely provide the needed demographic information. Contributing to attrition were high official transfer-out rates in many schools: an average of 16 percent of the students left each school during the seventh-grade year, and 19 percent during the eighth-grade year. Some of the study’s pretest respondents who transferred moved to other study schools and could continue to be tracked: 9 percent of all respondents in the posttest provided the name of a different school they had attended the preceding year. Overall attrition rates in the present study of Mexican/Mexican American respondents (4.6 percent per year) were not significantly different from those found for non-Hispanic white and African American students (5.1 percent, and 5.9 percent, respectively). Information from all students of Mexican heritage was used in the analysis, regardless of whether pre- and posttest records could be linked. However, the multiple imputation techniques for missing data made adjustments that allowed us to produce estimates based on information from all respondents—including those whose substance use attitudes, behaviors, and risk factors might have influenced attrition through school transfers, dropping out, and poor attendance.

The substance use outcome measures in the study were not highly intercorrelated, except for the composite measure of “overall” recent substance use, which was highly correlated (.69 to .81) with its three components (average of recent alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use). In contrast, the correlations among the three individual substance use indicators ranged from .11 to .39 and among the substance use norms and attitudes from .03 to .43.

Analysis proceeded in stages. To address the planned missingness and the missing data due to wave and item nonresponse, the software package NORM (Schafer, 1997; Schafer & Olsen. 1998) was used to generate 10 multiply imputed data sets. To preserve potential interaction effects, the imputations were performed separately for each condition of the study, and the 40 resulting data sets were recombined. Then, Weesie’s (2000) suest module for Stata (Stata Corporation, 2001) was used to fit four simultaneous regression models that tested hypotheses about group mean differences (for example, whether mean changes in substance use reported by students assigned to one of the intervention conditions equaled the mean change reported by students in the control condition). The four models examined overall substance use; separate alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use; personal, descriptive, and parents’ and friends’ injunctive norms; and refusal confidence, intentions to accept substance offers, and positive expectancies about substance use. By grouping together related outcome variables, the simultaneous regression models helped control the family-wise error rate. All of the models accounted for the school-level randomization with the accompanying nesting of students within school. (With group assignment to a study condition, responses of students from the same school are expected to be more similar to each other than are the responses of any two students chosen at random.) The number of participants from the 35 study schools (that is, the cluster size) ranged from 30 to 460, with Latino students being the majority group in more than three-fourths of the schools.

For each imputed data set, students’ change scores on a given outcome were regressed on their baseline scores and on a dummy variable for study condition. Thus, the dependent variable is a change score adjusted for baseline differences in a regression model that is equivalent to an analysis of co-variance on posttest scores (see Huitema, 1987). The estimates of the adjusted mean difference between intervention and comparison groups on the outcome measure and the variance of each mean difference were written out to a data file that also collected this information for the remaining multiply imputed data sets. Finally, following Rubin’s (1987) rules, the 10 sets of estimates were combined to test the hypothesis that the mean change reported by the intervention students equaled that reported by controls. To determine if the versions were differentially effective, additional analyses compared change scores for students in one version of the intervention to those in each of the Other versions.

RESULTS

Demographic Profile

Among all Mexican and Mexican American respondents, 82 percent qualified for a free lunch and 7 percent qualified for reduced-price lunch under the federal program for low-income students. At baseline the mean age was 12.52 years (SD = .64 years). The sample was 48.5 percent female. A substantial proportion of the students spoke Spanish as their native language, with approximately 8 percent choosing to complete the study questionnaires in Spanish rather than English. About 14 percent reported that they spoke mostly Spanish or only Spanish with their friends, and 31 percent reported that they spoke mostly or only Spanish with their families. The respondents attended schools where Latinos were usually in the majority (27 of 35 schools), often as members of super-majorities where more than 70 percent of the students were Latino (19 of 35 schools).

Program Participation

More than 91 percent of the Mexican and Mexican American students in the 25 intervention schools reported having seen at least one of the keepin’ it REAL videos during seventh grade and more than 30 percent reported seeing all five; 62 percent reported seeing the public service announcements at least once (compared with 31 percent of the control students); and 68 percent reported attending a booster activity during the period that they were offered.

Mean Changes Over Time

Substance use increased from the pre-intervention questionnaire to the 14-month follow-up for students in all conditions (Table 1). Reported alcohol and marijuana use increased the most, with much smaller increases in cigarette use. In comparison with controls, students in each intervention condition reported smaller increases in use of all three substances. Intervention students also tended to report relatively more desirable outcomes on all other outcomes. (The means in Table 1 were not adjusted for possible pre-intervention differences among students in the schools assigned to each intervention condition or to the control group.)

Table 1.

Unadjusted Mean Differences and Standard Errors from Pretest to Posttest for Intervention Conditions and the Control Group, All Mexican Heritage Students

| Variable | Control (N = 1,005) |

All Intervention (N = 2,397) |

Latino Version (N = 728) |

Non-Latino Version (N = 674) |

Multicultural Version (N = 995) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | |

| Recent substance use | .36 | .04 | .17 | .04 | .15 | .06 | .17 | .09 | .19 | .04 |

| Alcohol | .52 | .07 | .26 | .05 | .25 | .09 | .27 | .13 | .25 | .07 |

| Cigarettes | .16 | .05 | .06 | .03 | .03 | .06 | .03 | .05 | .11 | .04 |

| Marijuana | .41 | .07 | .20 | .04 | .15 | .07 | .22 | .11 | .22 | .05 |

| Refusal confidencea | −.10 | .06 | .08 | .05 | .11 | .06 | .07 | .10 | .06 | .09 |

| Intent to accept | .21 | .03 | .13 | .03 | .10 | .05 | .12 | .05 | .15 | .03 |

| Positive expectancies | .11 | .05 | .00 | .03 | .06 | .07 | .01 | .07 | .00 | .03 |

| Norms | ||||||||||

| Personal antidruga | −.20 | .03 | −.08 | .04 | −.04 | .09 | −.10 | .05 | −.10 | .06 |

| Parents’ injunctivea | −.07 | .03 | −.05 | .03 | −.03 | .07 | −.06 | .06 | −.06 | .03 |

| Friends’ injunctivea | −.23 | .05 | −.10 | .04 | −.08 | .08 | −.09 | .08 | −.12 | .05 |

| Descriptive | .25 | .04 | .12 | .05 | .00 | .12 | .20 | .06 | .16 | .08 |

For these four outcomes, larger change scores in the positive direction are desired; negative scores are desired for all other outcomes.

Intervention students reported an increase in refusal confidence, whereas control students reported less confidence in their ability to refuse substance offers. In the aggregate students from all conditions reported stronger intention or likelihood of accepting substance offers over time, yet control students reported larger increases than intervention students. In addition, both control and intervention students reported a weakening in three types of antidrug norms—personal, parental injunctive, and friend’s injunctive; however, control students reported larger decreases than did intervention students. The trend toward more undesirable change for control than for intervention students also appeared for positive expectancies of substance use and estimates of substance-using peers (descriptive norms), with some versions of the intervention reporting no net change while control students moved more sharply in the undesired direction.

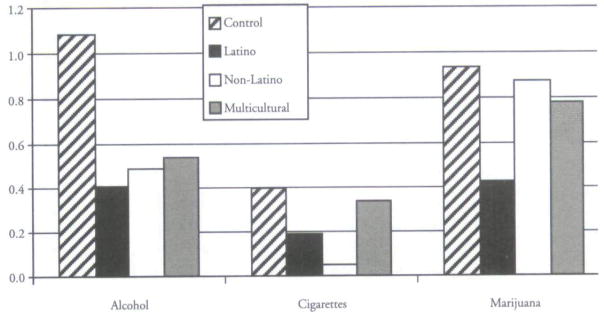

Overall, students participating in the intervention reported less harmful or more beneficial change than did control students (Table 1). Figure 1 illustrates the nature and relative size of some of these effects. The graph demonstrates increases from pretest to posttest in mean scores for the estimated number of days that students reported using particular substances in the past 30 days, using transformations of the original reports on frequency of use that, in Tables 1, 2, and 3, are used as outcomes in combination with amounts of substance use. The sample used for the graph includes only cases matched from pretest to posttest who reported pertinent data at both times. Although the mean days of use increased for the control and the intervention students, the control students reported larger increases in use. In the case of alcohol, days of substance use among intervention students was less than half the mean reported by control students. For all three substances, students in the Latino version of the program demonstrated consistently more desirable outcomes, again reporting about half the number of days of use reported by control students. Testing for the statistical significance of these differences, however, required additional analyses.

Figure 1.

Pretest to Posttest Increase in Mean Number of Days of Substance Use in Last 30 Days, by Condition and Substance

Table 2.

Mean Differences between Each Intervention Condition and the Control after Accounting for Pre-Intervention Differences, All Mexican Heritage Students

| Variable | All Intervention versus Control (N =3,402) |

Latino Version versus Control (N = 1,733) |

Non-Lationo verson versus Control (N = 1,679) |

Multicultural Version versus Control (N = 2,000) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | Est. | SE | |

| Recent substance use | −.17** | .06 | −.20** | .08 | −.16 | .10 | −.15* | .06 |

| Alcohol | −.22** | .09 | −.24 | .12 | −.17 | .14 | −.24** | .09 |

| Cigarettes | −.08 | .05 | −.12 | .07 | −.11 | .07 | −.03 | .06 |

| Marijuana | −.18* | .08 | −.24* | .09 | −.15 | .13 | −.16* | .08 |

| Refusal confidence | .16 | .08 | .23* | .09 | .11 | .11 | .16 | .09 |

| Intent to accept | −.07 | .04 | −.12* | .06 | −.06 | .05 | −.04 | .04 |

| Positive expectancies | −.09 | .05 | −.10 | .08 | −.07 | .06 | −.10 | .05 |

| Norms | ||||||||

| Personal antidrug | .10 | .06 | .15 | .09 | .06 | .07 | .08 | .06 |

| Parents’ injunctive | .00 | .04 | .04 | .07 | −.03 | .05 | .00 | .04 |

| Friends’ injunctive | .12 | .07 | .18 | .10 | .09 | .09 | .10 | .08 |

| Descriptive | −.08 | .06 | −.21* | .10 | −.05 | .09 | −.02 | .06 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

Table 3.

Mean Differences between the Non-Latino Version of the Intervention and the Latino and Multicultural Versions after Accounting for Pre-Intervention Differences, Students Identifying Exclusively as Mexican/Mexican American

| Variable | Latino version versus Non-Latino Version (N = 856) |

Multicultural Version versus Non-Latino Version (N = 1,017) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | SE | Est. | SE | |

| Recent substance use | −.02 | .14 | .01 | .13 |

| Alcohol | −.04 | .22 | −.09 | .20 |

| Cigarettes | .01 | .09 | .11 | .09 |

| Marijuana | −.09 | .17 | −.03 | .15 |

| Refusal confidence | .10 | .13 | .11 | .12 |

| Intent to accept | −.03 | .08 | .03 | .07 |

| Positive expectancies | .01 | .10 | −.03 | .07 |

| Norms | ||||

| Personal antidrug | .07 | .11 | .01 | .08 |

| Parents’ injunctive | .16 | .09 | .09 | .07 |

| Friends’ injunctive | .04 | .10 | −.02 | .07 |

| Descriptive | −.12 | .14 | .07 | .11 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Comparison of Intervention and Control Group Students

The intervention group reported significantly better outcomes than those reported by the control group on overall recent substance use, alcohol, and marijuana use, with intervention students demonstrating significantly smaller increases in recent substance use (Table 2). Although the other outcomes did not produce statistically significant effects, all pointed in the same direction, toward relatively more desirable outcomes in the intervention group than in the control group.

The Latino and multicultural versions of the intervention provided the clearest benefits to Mexican and Mexican American students. Compared with controls, students in the Latino version of the intervention reported significantly smaller increases in overall recent substance use, recent marijuana use, intentions to accept substances, and estimates of friends’ and peers’ drug use (descriptive norms) (Table 2). They also reported increases rather than decreases in drug refusal confidence. Students receiving the multicultural version of the intervention reported significantly smaller increases in overall recent substance use, recent alcohol use, and recent marijuana use. All of the remaining nonsignificant coefficients comparing the Latino and multicultural intervention versions with the control group were in the hypothesized desired direction. In contrast, none of the outcomes comparing the non-Latino condition to the control condition produced significant differences, with coefficients generally less sizable than for the other two intervention versions, and at times in the opposite direction of that desired (for example, parental injunctive norms). The pattern of significant effects showed that the Latino version produced a wider range of desired program effects than the other versions, encompassing a number of substance use mediators as well as actual substance use. Although the multicultural intervention was the only version to demonstrate significant effects on alcohol, the corresponding coefficient for the Latino version was equal in size, although nonsignificant. It appeared then that the Latino and multicultural versions performed better for Mexican and Mexican American students than did the non-Latino version. Analyses that compared versions of the interventions to one another provided an additional assessment of the relative value of cultural matching.

Comparisons of Latino and Multicultural Versions to Non-Latino Version

To assess whether cultural specificity enhanced the effects of the intervention, we used simultaneous regression models to fit data provided only by students in the three intervention conditions (Table 3). The models controlled for baseline differences and nesting of students within school and adjusted for missing data. The expectation was that Mexican and Mexican American students who received the Latino or multicultural versions of the intervention would report more positive outcomes than would those who received the Non-Latino version. The analyses did not support this expectation as no significant differences emerged among the three versions of the intervention. Even when analysis limited the sample to students who reported an exclusively Mexican/Mexican American ethnic identity—a group for whom cultural matching of program content to student ethnicity produces an unambiguous match to the Latino version and a mismatch to the Non-Latino program—the Latino version did not produce significantly better outcomes than the non-Latino version.

DISCUSSION

This study provides some evidence for the efficacy of a culturally grounded substance use prevention program tailored to Mexican and Mexican American middle school students, a group for which few culturally specific prevention efforts have been developed or tested. Compared with students in the control schools, the students who participated in keepin’ it REAL reported beneficial effects on recent alcohol and marijuana use, future intentions to accept substance offers, confidence to refuse substance offers, and more realistic perceptions of peer substance use. During a developmental period where experimentation with substance use rises sharply, participation in this program retarded the students’ transitions to elevated levels of substance use and their adoption of pro-drug attitudes and norms. There was no evidence of harmful program effects, and no program participants reported significantly more undesirable substance use outcomes than students in the control schools. Indeed, the direction of unadjusted mean differences from pretest to posttest on every outcome pointed to more sizable undesirable changes in the control group than for students in each version of the intervention. At the critical time of entry into adolescence from seventh to eighth grade, the keepin’ it REAL program showed significant desirable effects in delaying initiation and slowing increases in the amount and frequency of use of key “gateway” substances (alcohol and marijuana) as well as restraining the adoption of pro-drug attitudes and norms such as intentions to use substances and perceptions of substance-using peers. In one instance—drug refusal confidence—the program appeared to strengthen resilience against drug use, rather than merely retard its erosion.

Results were less clear, however, regarding the importance of strict cultural matching of program content with student ethnicity. On the one hand, all of the significant program effects were confined to the Latino and multicultural versions of the curriculum that specifically targeted Mexican American cultural orientations. In line with our general hypothesis, the Latino curriculum appeared to be the most effective as judged by its beneficial impact on a wide array of substance use and attitudinal outcomes, with the multicultural program producing significant effects on alcohol and marijuana use only, and the non-Latino program reporting no significant differences in comparison with controls. Because the majority of the students were not using substances even at posttest, the findings showing significant desired effects on mediators of substance use (intention to use, confidence in refusing drug offers, and descriptions of peer use) take on special importance, and all these effects were confined to the Latino version. Thus, the pattern of significant effects followed the expected order of effectiveness for the program versions.

On the other hand, no statistically significant differences emerged in direct contrasts of the effectiveness of the Latino and multicultural curriculums compared with the non-Latino version. The lack of statistical support for strict cultural matching, however, does not obviate the evidence from this study that prevention messages incorporating cultural elements of the target population provide greater efficacy. One way to interpret the findings is that they indicate the importance of cultural inclusion rather than cultural exclusivity in program content. The lack of significant beneficial impact of the non-Latino version of the program suggests that ignoring the culture of Mexican American students may compromise the impact of prevention programs in which they participate. At the same time, the demonstrated effectiveness of both the Latino and multicultural versions of the program, both of which included representative Mexican American cultural elements, suggests that such elements may need to be present, although not necessarily to the exclusion of other cultural representations.

These evidence-based results advance the field of prevention with Mexican and Mexican American students by underlining the importance of acknowledging and integrating norms from the students’ culture of origin into program content. The fact that the multicultural version of the program showed many benefits indicates that it may not be necessary, or in some cases even desirable, to narrowly tailor prevention messages to each specific cultural group (Latinos) or subgroup (Mexican Americans). One explanation for its effectiveness may be that it can address variations in the acculturation level of Mexican and Mexican American students at various stages of blending, accommodating, or integrating their culture of origin with the dominant culture.

Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Careful interpretation of this study’s findings requires an awareness of several limitations related to the complex experimental design, comparison of newly created program versions to one another rather than to a standard version, contamination, dosage and attrition issues, and generalizability beyond the local cultural environments. Despite block randomization in the assignment of schools to one of three versions of the intervention or to the control condition, it is possible that the groups differed in unexpected and unmeasured ways that affected the study outcomes. The Latino and non-Latino versions were developed independently around common prevention principles, but there was not a “standard” version against which the other versions could be compared for effectiveness. Despite attempts to represent each drug resistance skill in each version of the curriculum, differences may have arisen in emphasis or in successful incorporation of cultural content, thereby influencing the outcomes beyond the effects of cultural grounding. Student transfers and teacher interactions between schools in different intervention or control conditions could introduce some contamination of program content. Dosage was neither controlled in the implementation nor incorporated into the current analysis, and measures of some aspects of dosage (curriculum sessions attended) were unavailable. Although advanced methods for handling missing data compensated to a marked degree, there were substantial respondent attrition and record-linking difficulties across waves. Although some of these limitations might work in the opposite direction, it is likely that most of them compromised rather than exaggerated assessments of program effectiveness. Although Figure 1 suggested sizable desirable effects of the intervention, and Table 2 demonstrated them to be statistically appreciable, conventional program effect sizes could not be calculated because of the multivariate approach we used and the presence of school-level nested effects.

The embedded development of the program within particular local youth cultures makes it unclear how well it would generalize to other Mexican American communities, areas outside Phoenix and the Southwest, or schools where Mexican American students are a numerical minority or come from higher socioeconomic backgrounds (unlike most of the study sample). School demographics limited our ability to develop separate versions of the curriculum for non-Hispanic black and white students, leading to the creation of a single non-Latino version that incorporated elements of both those cultures. Study replications in areas with different ethnic distributions need to ensure that the curriculum adequately reflects the local ethnic composition.

Research into the impact of cultural matching of program content may need to take into account not only the self-reported ethnic identity of the student, but also the salience of that identity and levels of acculturation into mainstream society (Vega & Gil, 1998). The possible reasons for the effectiveness of culturally grounded programs require further exploration as well. There may be more than the direct benefits to students who now see their cultures represented in the prevention message. We need to understand in depth how these interventions transform school culture, affect students from different cultural groups, and expand the cultural awareness and competence of teachers and administrators.

Implications for Social Work Practice

The development, implementation, and evaluation of the keepin’ it REAL curriculum provide examples of key elements of evidence-based practice, with important implications for linkages between school social work practice and research. School social workers have a key role as members of research teams as they engage in curriculum assessment, development, and testing. The social worker can be a broker between cultural and community needs, the school administration, and the researchers and curriculum developers. Some existing evidence-based models are applicable in their original format, yet others need to be adapted to the local social context. If adaptations are made, issues of fidelity need to be considered and a rigorous evaluation must be conducted.

School social workers cannot respond alone to the multiple psychosocial needs related to substance use that are presented by the school population. They can identify appropriate evidence-based interventions, such as keepin’ it REAL that incorporate strengths from the students’ cultures of origin and advocate for their adoption. Such a process will solidify partnerships between classroom teachers and social workers in implementing effective prevention interventions that reach the “whole” child. When available models do not serve particular cultural communities, teams conducting curriculum development and testing should be expanded to incorporate prevention researchers and other school constituencies. The designation of keepin’ it REAL as a model program by SAMSHA (2003) demonstrates the potential for social work, prevention research, and school-community partnerships to create school curriculums that reflect their students’ cultures.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse grants funding the Next Generation of Drug Abuse Prevention Research project (R01 DA14825), the Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Center at Arizona State University (R24 DA13937), and the Drug Resistance Strategies III project (R01 DA05629).

Contributor Information

Stephen Kulis, Email: kulis@asu.edu, Professor, Department of Sociology and director of research, Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Center, Arizona State University, Box 87371l, Tempe, AZ 85287-3711.

Flavio F. Marsiglia, Professor, School of Social Work, Arizona State University, Tempe.

Elvira Elek, Project director, Drug Resistance Strategies Project, Pennsylvania State University, University Park.

Patricia Dustman, Director of implementation and Development, Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Center, Arizona State University.

David A. Wagstaff, Associate director, Methodology Center.

Michael L. Hecht, Professor, Department of Communication Arts and Sciences, Pennsylvania State University, University Park.

References

- Bandura A. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs. NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Bogenschneider K. An ecological risk protective theory for building prevention programs, policies, and community capacity to support youth. Family Relations. 1996;45(2):127–138. [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ, Epstein JA, Baker E, Diza T, Ifill-Williams M, Miller N, Caldwell J. School-based drug abuse prevention with inner-city minority youth. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse. 1997;6:5–19. [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ, Griffin KW, Diaz T, Ifill-Williams M. Drug abuse prevention among minority adolescents: Posttest and one-year follow-up of a school-based preventive intervention. Prevention Science. 2001;2:1–13. doi: 10.1023/a:1010025311161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Proescholdbell RJ, Abeita L, Rodriguez D. Ethnic and cultural minority groups. In: McCrady BS, Epstein EE, editors. Addictions: A comprehensive guidebook. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999. pp. 499–526. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini R, Reno R, Kallgren C. A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:1015–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Dorr A. Television and the socialization of the minority child. In: Mitchell-Kernan GI, Mitchell-Kernan C, editors. Television and the socialization of the minority child. New York: Academic Press; 1982. pp. 15–36. [Google Scholar]

- Eigen ZD, Siegel JD. Communicating health messages to high-risk youth: OSAP’s “Don’t do drugs, call a friend” billboard campaign. Presentation at the annual meeting of the International Communication Association; Chicago. 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, Bell RM. Drug prevention in junior high: A multi-site longitudinal test. Science. 1990;247:1299–1305. doi: 10.1126/science.2180065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W. Human communication as narration: Toward a philosophy of reason, value, and action. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Flannery DJ, Vazsonyi AT, Torquati J, Fridrich A. Ethnic and gender differences in risk for early adolescent substance use. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1994;23:195–213. [Google Scholar]

- Gosin M, Marsiglia FF, Hecht ML. Keepin’ it REAL: A drug resistance curriculum tailored to the strengths and needs of pre-adolescents of the Southwest. Journal of Drug Education. 2003;33:119–142. doi: 10.2190/DXB9-1V2P-C27J-V69V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Flay BR, Johnson CA. Reliability of self-report measures of drug use in prevention research: Evaluation of the Project SMART questionnaire via the test-retest reliability matrix. Journal of Drug Education. 1984;14:175–193. doi: 10.2190/CYV0-7DPB-DJFA-EJ5U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Hofer SM, MacKinon DP. Maximizing the usefulness of data obtained with planned missing value patterns: An application of maximum likelihood procedures. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1996;31:197–218. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3102_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Hofer SM, Piccinin AM. Analysis with missing data in drug prevention research. In: Collins LM, Seits L, editors. Advances in data analysis for prevention intervention research (National Institute of Drug Abuse Research Monograph Series No. 142) Washington, DC: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Taylor BJ, Cumsille PE. Planned missing data designs in analysis of change. In: Collins L, Sayer A, editors. New methods for the analysis of change. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001. pp. 335–353. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen WB. School-based substance abuse prevention: A review of the state of the art in curriculum, 1980–1990. Health Education Research. 1991;7:403–430. doi: 10.1093/her/7.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen WB, Graham JW. Preventing alcohol, marijuana, and cigarette use among adolescents: Peer pressure resistance training versus establishing conservative norms. Preventive Medicine. 1991;20:414–430. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(91)90039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen WB, Johnson CA, Flay BR, Graham JW, Sobel JL. Affective and social influences approaches to the prevention of multiple substance abuse among seventh grade students: Results from project SMART. Preventive Medicine. 1988;17:135–154. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(88)90059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harthun ML, Drapeau AE, Dustman PA, Marsiglia FF. Implementing a prevention curriculum: An effective researcher-teacher partnership. Education and Urban Society. 2002;34:353–364. [Google Scholar]

- Hecht ML, Ribeau S. Ethnic communication: A comparative analysis of satisfying communication. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 1984;8:135–151. [Google Scholar]

- Hecht ML, Ribeau S, Alberts JK. An Afro-American perspective on interethnic communication. Communication Monographs. 1989;56:385–410. [Google Scholar]

- Hecht ML, Ribeau S, Sedano MV. A Mexican American perspective on interethnic communication. International journal of Intercultural Relations. 1990;14:31–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hecht ML, Marsiglia FF, Elek E, Wagstaff DA, Kulis S, Dustman P. Culturally grounded substance use prevention: An evaluation of the keepin’ it REAL curriculum. Prevention Science. 2003;4(4):233–248. doi: 10.1023/a:1026016131401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holleran L, Dustman P, Reeves L, Marsiglia FF. Creating culturally grounded videos for substance abuse prevention: A dual perspective on process. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions. 2002;2(1):55–78. [Google Scholar]

- Huitema BE. The analysis of covariance and alternatives. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD. The survey technique in drug abuse assessment. Bulletin of Narcotics. 1989;41(1–2):29–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG. Secondary school students (NIH Publication No. 00–4802) I. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2000. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB. Ethnic differences in drug use: Patterns and paradoxes. In: Botvin GJ, Schinke S, Orlandi MA, editors. Drug abuse prevention with multiethnic youth. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1995. pp. 81–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kasen S, Vaughan RD, Walter HJ. Self-efficacy for AIDS preventive behaviors among 10th grade students. Health Education Quarterly. 1992;9:187–202. doi: 10.1177/109019819201900204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochman T. Black and white styles in conflict. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Holleran L. I’ve learned so much from my mother: An ethnography of a group of Chicana high school students. Social Work in Education. 2000;21:220–237. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Hecht ML. Ethnic-labels and ethnic identity as predictors of drug use and drug exposure among middle school students in the Southwest. journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11:21–48. [Google Scholar]

- National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse. Cigarettes, alcohol and marijuana: Gateways to illicit drug use (CASA report) New York: Columbia University; 1994. Jun, [Google Scholar]

- National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse. Teen tipplers: America’s underage drinking epidemic (CASA report) New York: Columbia University; 2002. Feb, [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. Reliability and consistency in self-reports of drug use. International Journal of the Addictions. 1983;18:806–824. doi: 10.3109/10826088309033049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polansky JM, Buki LP, Hran JJ, Ceperich SD, Burows DD. The effectiveness of substance abuse prevention videotapes with Mexican American adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1999;21:186–198. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez G. Forcing a new vision of America’s melting pot. New York Times [Week in Review] 2001 February 11;section 4:1, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL. Analysis of incomplete multivariate data. New York: Chapman and Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Olsen MK. Multiple imputation for multivariate missing-data problems: A data analyst’s perspective. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 1998;33:545–571. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3304_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Donals LG, Klitzner MD. Self-reports of youthful drinking and driving: Sensitivity analyses of sensitive data. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 1985;17:179–190. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1985.10472339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stata Corporation. Stata Statistical Software: Release 7.0. College Station, TX: Author; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA Model Programs. 2003 Retrieved May 9,2005, from http://www.modelprograms.samhsa.gov/

- Vasconcelos J. The race problem in Latin America. In: Vasconcelos J, Gamio M, editors. Aspects of Mexican civilization. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1926. pp. 75–104. [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Gil AG. Drug; use and ethnicity in early adolescence. New York: Plenum Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Weesie J, Newton HJ. Seemingly unrelated estimation and the cluster-adjusted sandwich estimator. Stata Technical Bulletin Reprints. 2000;9:231–248. [Google Scholar]