Abstract

The recent proposal that Dra/Slc26a3 mediates electrogenic 2Cl−/1HCO3− exchange suggests a required revision of classical concepts of electroneutral Cl− transport across epithelia such as the intestine. We investigated 1) the effect of endogenous Dra Cl−/HCO3− activity on apical membrane potential (Va) of the cecal surface epithelium using wild-type (WT) and knockout (KO) mice; and 2) the electrical properties of Cl−/(OH−)HCO3− exchange by mouse and human orthologs of Dra expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Ex vivo 36Cl− fluxes and microfluorometry revealed that cecal Cl−/HCO3− exchange was abolished in the Dra KO without concordant changes in short-circuit current. In microelectrode studies, baseline Va of Dra KO surface epithelium was slightly hyperpolarized relative to WT but depolarized to the same extent as WT during luminal Cl− substitution. Subsequent studies indicated that Cl−-dependent Va depolarization requires the anion channel Cftr. Oocyte studies demonstrated that Dra-mediated exchange of intracellular Cl− for extracellular HCO3− is accompanied by slow hyperpolarization and a modest outward current, but that the steady-state current-voltage relationship is unaffected by Cl− removal or pharmacological blockade. Further, Dra-dependent 36Cl− efflux was voltage-insensitive in oocytes coexpressing the cation channels ENaC or ROMK. We conclude that 1) endogenous Dra and recombinant human/mouse Dra orthologs do not exhibit electrogenic 2Cl−/1HCO3− exchange; and 2) acute induction of Dra Cl−/HCO3− exchange is associated with secondary membrane potential changes representing homeostatic responses. Thus, participation of Dra in coupled NaCl absorption and in uncoupled HCO3− secretion remains compatible with electroneutrality of these processes, and with the utility of electroneutral transport models for predicting epithelial responses in health and disease.

Keywords: anion exchange, bicarbonate secretion, cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator, mouse, NaCl absorption

two members of the Slc26 family of multifunctional anion exchangers provide apical membrane Cl−/HCO3− exchange function in most alimentary epithelia and therefore play critical roles in the processes of Cl− absorption and HCO3− secretion. Slc26a3 (downregulated in adenoma, Dra) is expressed abundantly in segments of the intestine (1, 25). Slc26a6 (putative anion transporter-1, Pat-1) is expressed primarily in the small intestine where it contributes to fluid absorption and epithelial pH regulation, especially during nutrient transport. Dra, together with the Na+/H+ exchanger Nhe3, provides the classical function of coupled NaCl absorption (26, 43). Coupled NaCl absorption is considered an electroneutral process based on isotopic flux studies showing high rates of transepithelial ion transfer unassociated with analogous changes in transepithelial potential or short-circuit current (Isc) (29). The cation-anion coupling is thought to be intracellular pH (pHi)-dependent (13, 41), a hypothesis supported by studies of knockout (KO) mice and of recombinant proteins (10, 18). Genetic ablation of Dra in murine villous epithelium results in an alkaline pHi, and knockout of Nhe3 results in an acidic pHi, but pharmacological inhibition of either transporter when expressed with the other does not affect pHi (43). The importance of Dra in intestinal NaCl absorption is emphasized by loss-of-function mutations that cause the human disease congenital Cl− losing diarrhea, a disorder that is recapitulated in Dra KO mice (10, 20, 25, 31). Inflammatory and enteropathic diarrhea in humans and rodents, especially those associated with microvillar effacement pathology, decrease Dra expression (3, 4, 17, 49), whereas mucosal exposure to certain probiotic species upregulates Dra expression (30). In the duodenum, “uncoupled” Cl−/HCO3− activity of Dra contributes to the alkaline mucus barrier against gastric acid effluent by providing most basal HCO3− secretion and a portion of cAMP-stimulated HCO3− secretion (42).

Investigations into the transport stoichiometry and electrical properties of Dra and Pat-1 have yielded discrepant findings, especially with regard to functional expression studies of Dra. Several factors likely contribute to the difficulties in interpretation. Slc26 polypeptides are not exclusively anion exchangers, as overexpression of Slc26a9 and Slc26a7 increases anion conductance (27) as well as, in some studies, Cl−/HCO3− exchange (2, 47, 48). Electrophysiological studies of overexpressed Dra and Pat-1 demonstrate uncoupled conductance of SCN− and NO3−, which raises questions about possible concurrent conductive Cl− movement during exchange activity (27). However, Cl− conductive activity has yet to be detected by single-channel recordings of these transporters. Pat-1 and Dra also have regulatory properties as demonstrated by alterations in Cftr anion channel activity through interaction of the Slc26 transporters' STAS domain with Cftr's R domain (23). Multiple studies concur that mouse Pat-1-mediated Cl−/oxalate2− exchange is electrogenic (9, 19, 22, 46). Most, though not all (9), studies of Pat-1-mediated Cl−/HCO3− exchange in Xenopus oocytes have demonstrated hyperpolarization of the membrane potential (Vm) during extracellular Cl− removal (19, 22, 46), accompanied by net ion fluxes favoring a 1Cl−/2HCO3− exchange stoichiometry (32).

In the case of Dra, discrepant findings of Cl−-dependent changes in Vm have fueled controversy. One laboratory has shown strong depolarization of Vm in Xenopus oocytes expressing murine Dra during removal of extracellular Cl− in HCO3−-free medium (i.e., Cl−/OH− exchange) (22). However, depolarization was reduced nearly to background levels by inclusion of CO2/HCO3− in the superfusate (22, 32), a condition which minimally changed concomitant currents measured at +60 mV while increasing Cl−/base exchange activity. In subsequent investigations using ion-selective microelectrodes, murine Dra exhibited an electrogenic 2Cl−/1HCO3− exchange stoichiometry based on the ratio of Cl− and HCO3− transport rates (32). From this and earlier studies (22, 23), it was proposed that the electroneutral Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity observed in past transepithelial flux measurements reflected simultaneous, possibly coupled, Dra and Pat-1 activities of equal magnitude and opposite electrogenic stoichiometries. However, other studies of human DRA expression in Xenopus oocytes demonstrated modest hyperpolarization of Vm during extracellular Cl− substitution, although the small Cl−-dependent changes in Vm (10) were within the range reported by others for water-injected oocytes (46). This study, and others on guinea pig Dra (38), concluded that Cl−/HCO3− exchange by DRA is electroneutral. Three additional studies expressing either murine Dra or human DRA in HEK293 or CHO cells further supported electroneutrality of transport by showing that Cl−/HCO3− exchange function was unaffected by cell depolarization induced by high external K+ concentration (18, 24, 25).

The question of Dra electrogenicity has important consequences for our understanding of electrolyte transport in mammalian epithelia during health and disease. The prediction of responses and identification of appropriate targets for therapy during disturbances of electrolyte transport will be altered depending on whether or not Dra activity is directly linked to changes in Vm. For example, in the intestine, the concurrent activity of electrogenic transporters such as Na+ or H+-coupled solute transporters (e.g., Sglt1) would be predicted to upregulate the processes of NaCl (+ water) absorption and HCO3− secretion if Dra-mediated Cl−/HCO3− exchange is electrogenic. These important considerations prompted our evaluation of the effect of Dra activity on Vm in the physiological setting of the native intestinal epithelium. The surface epithelium of murine cecum was chosen for study due to its expression of Dra at very high levels, its low abundance of Pat-1 transcripts, and the availability of knockout mouse models for both transporters to evaluate Dra's contribution to Vm (1, 25, 45). Recent studies verify high rates of Dra functional activity in the murine cecum, corresponding to the role of this organ in buffering short-chain fatty acid production during intense microbial digestion in the large intestine (39). In this physiological context we also revisited the varied, previous reports of Dra-mediated Cl−-dependent changes in Vm by expressing murine Dra and human DRA in the Xenopus oocyte system for electrophysiological analysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Mice with gene-targeted disruption of the murine homologs of Slc26a3 (Dra, a kind gift from C. W. Schweinfest, Medical University of South Carolina) (31), Slc26a6 (Pat-1, a kind gift from M. Soleimani, University of Cincinnati,) (44) and Cftr (35) were used. All comparisons were made with sex- and age-matched (+/+) siblings [wild type (WT)]. Dra/Cftr double-knockout mice were generated from male Dra(+/−), Cftr(−/−) and female Dra(+/−), Cftr(+/−) breeder pairs. The mutant mice were identified using a PCR-based analysis of tail snip DNA, as previously described (12). All mice were maintained ad libitum on standard laboratory chow (Formulab 5008 Rodent Chow; Ralston Purina) and tap water. The Dra KO and littermate mice were treated with 50% Pedialyte in the drinking water to avoid dehydration due to chronic diarrhea (43). The Cftr KO, Dra/Cftr double KO, and littermate mice were treated with Colyte laxative in the drinking water to avoid intestinal obstruction (12). All mice were housed singly in a temperature (22–26°C) and light (12:12-h light-dark cycle)-controlled room in the AAALAC-accredited animal facility at the Dalton Cardiovascular Research Center, University of Missouri. Intestinal tissues for experiments were obtained from mice 2–4 mo of age. Mice were fasted overnight prior to experimentation but were provided with water ad libitum. All experiments involving animals were approved by the University of Missouri Animal Care and Use Committee.

Transepithelial 36Cl flux analysis.

The method for transepithelial 36Cl flux across murine intestine has been previously described (43). Briefly, bisected halves of excised cecum from each mouse were stripped of external muscle layers before mounting on Ussing chambers (0.25 cm2 surface area). Transepithelial short-circuit current (Isc, μeq·cm−2·h−1) and conductance (Gt, mS/cm2) were measured using an automatic voltage clamp (VCC-600, Physiologic Instruments, San Diego, CA). Mucosal and serosal sides of each section were independently bathed with Krebs bicarbonate Ringer solution (KBR) gassed with 95% O2-5% CO2 (pH 7.4, 37°C). All ex vivo preparations were treated with indomethacin (1 μM, bilateral) and tetrodotoxin (0.1 μM, serosal) to minimize the effects of endogenous prostaglandins and neural tone, respectively (5, 43). The mucosal bath contained 10 μM amiloride to eliminate any contribution of epithelial Na channel (ENaC) activity to the Isc. Approximately 3 μCi of 36C1 were added to the “source” bathing medium and, following a 30 min equilibration period, triplicate aliquots (200 μl) were taken from the “sink” side at the beginning and end of the 30 min flux period. Samples were analyzed for 36Cl− by liquid scintillation counting (Packard Instruments, Meriden, CT). The rate of radioisotope transfer was used to calculate unidirectional mucosal-to-serosal (JM−S), serosal-to-mucosal (JS-M), and net fluxes (JNET = JM−S − JS-M) of Cl−. From individual mice, only paired cecal preparations with Gt values differing by <15% were selected for calculation of mean values of JNET. For net fluxes, a positive value indicates net absorption (mucosal-to-serosal) and a negative value indicates net secretion (serosal-to-mucosal).

Intracellular pH measurement in intact mucosa.

The method used for imaging epithelial cells in intact murine intestinal mucosa has been previously described (33). Briefly, mid-cecal sections stripped of external muscle layers were mounted luminal side up in a horizontal Ussing-type perfusion chamber where luminal and serosal surfaces were independently bathed. The mucosa was incubated on the luminal side with 16 μM of BCECF-AM for 10 min before superfusion of the luminal surface. The luminal superfusate contained (in mM) 55.0 NaCl, 55.0 Na isethionate, 25.0 NaHCO3, 5.0 Na TES, 2.4 K2HPO4, 0.4 KH2PO4, 2.4 Ca gluconate, 2.4 Mg gluconate, 10.0 glucose, and 6.8 mannitol (pH 7.4, 37°C; gassed with 95% O2-5% CO2). The serosal superfusate was identical except Cl− was replaced with isethionate− and contained 1 μM EIPA to block the basolateral membrane Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 1. pHi from 10 villous epithelial cells was measured by dual excitation at 440- and 495-nm wavelengths and imaged at 535-nm emission. The 495:440-nm ratios were converted to pHi using a standard curve generated by the K+/nigericin technique (40). Rates of apical membrane Cl−/HCO3− exchange are reported as ΔpHi/Δt during the first 90-s period during removal and readdition of Cl− in the luminal superfusate.

Intracellular microelectrodes.

Freshly excised ceca were thoroughly rinsed with ice-cold KBR, everted, and filled with ∼0.25 ml of freshly gassed KBR (37°C) containing 5 mM TES, 1.0 μM indomethacin, and 0.1 μM TTX. The cecum was clamped near the cecocolic junction and incubated for 5 min with gentle agitation in KBR containing 100 μM dl-dithiothreitol. After rinsing with fresh KBR, the cecal preparation was secured in an open, glass-bottomed chamber placing the greater curvature in profile, and superfused with KBR + 5 mM TES containing 10 μM amiloride at either room temperature or 37°C, as indicated.

The method for construction and use of microelectrodes in mammalian epithelium has been previously described (11). Cellular impalements were performed perpendicular to the apical surface at ∼0.5 cm proximal to the cecal apex under visual control using an Olympus IMT-2 inverted microscope and remote-controlled micromanipulator (Narishige MW-3). All impalements (∼5/cecum) were performed within 20 min using a conventional microelectrode backfilled with 500 μM KCl and connected via an Ag-AgCl pelleted holder to a high-impedance amplifier (Duo 773, World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL). Signal was acquired using a Digidata 1332A A-D converter and pCLAMP 8.0 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Microelectrodes were constructed from borosilicate glass capillary tubes (WPI) and pulled on a horizontal puller (Narishige PD-5). The resistance of the microelectrodes immersed in KBR + 5 μM TES averaged 112 MΩ (n = 28). A 3 M agar bridge connected the bath to a calomel half-cell which served as ground for the microelectrodes. The apical membrane potential (Va) was indicated by an instantaneous shift in the microelectrode signal which stabilized to within ±5 mV by 10 s. Impalements were accepted if sustained during substitution of bath Cl− with equimolar isethionate, and returned to within ±2 mV upon retraction of the microelectrode in Cl− containing KBR. Sign convention was chosen so that Va is referenced to the bath (lumen side).

Solutions for Xenopus oocytes.

ND-96 (pH 7.40) consisted of (in mM) 96 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5 HEPES, and 2.5 sodium pyruvate, and gentamycin 100 μg/ml. ND-96 flux medium and other flux media lacked sodium pyruvate and gentamycin. pH values of 7.4 and 8.0 in room air flux media were achieved with 5 mM sodium HEPES. In Cl−-free solutions, 96 mM NaCl was replaced isosmotically with 96 mM sodium gluconate, sodium isethionate, or sodium cyclamate as indicated. The Cl− salts of K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+ were substituted with the corresponding equimolar gluconate salts. HEPES-free CO2/HCO3−-buffered solutions of pH 7.4 were saturated with 5% CO2-95% air at room temperature for ∼1 h, and substituted 24 mM NaHCO3 in place of 24 mM NaCl or Na gluconate or isethionate. The pH of CO2/HCO3−-buffered solutions was verified prior to each experiment.

Isotopic flux studies in Xenopus oocytes.

Unidirectional 36Cl− influx studies were carried out in ND-96 as previously described for 30 min period (10). Total bath Cl− concentration ([Cl−]) was 104 mM. Unidirectional 36Cl− efflux studies were as described by Chernova et al. (10). Individual oocytes in Cl−-free ND-96 were injected with 50 nl of 130 mM Na36Cl (10,000–12,000 cpm). Following a 5–10 min recovery period, the efflux assay was initiated by transfer of individual oocytes to 6 ml borosilicate glass tubes, each containing 1 ml efflux solution. At intervals of 3 min, 0.95 ml of this efflux solution was removed for scintillation counting and replaced with an equal volume of fresh efflux solution. Following completion of the assay with a final efflux period in the absence of bath chloride (substituted by Na isethionate and by gluconate salts of K, Ca, and Mg), each oocyte was lysed in 100 μl of 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). Samples were counted for 3–5 min such that the magnitude of 2SD was <5% of the sample mean.

Experimental data were plotted as ln(% cpm remaining in the oocyte) vs. time. 36Cl− efflux rate constants were measured from linear fits to data from the last three time points sampled for each experimental condition. Within each experiment, water-injected and DRA cRNA-injected oocytes from the same frog were subjected to parallel measurements. Each experimental condition was tested in oocytes from at least two frogs.

Measurement of oocyte pHi.

Oocyte pHi was measured using pH microelectrodes during bath superfusion as described previously (36). The pH microelectrodes were pulled on a Kopf Model 730 vertical puller (Tujunga, CA) and had resistances of 2–3 MΩ. The electrodes were calibrated at pH 6.0, 7.0, and 8.0, and exhibited slopes of at least 55 mV/pH unit. Proton-equivalent flux (JH+ in units of mM/min) was calculated as ΔpHi/Δt × βT, where total buffer capacity (βT) = βi + βCO2. βi is intrinsic buffer capacity of the oocyte, 20 mM/pH unit (37). The HCO3−/CO2-related component of the buffer capacity, βCO2 = 2.3 × [HCO3−]i.

Two-electrode voltage clamp measurement of oocyte current.

Microelectrodes from borosilicate glass made with a Narishige puller were filled with 3 M KCl and had resistances of 2–3 MΩ. Oocytes were placed in a 1 ml chamber (model RC-11, Warner Instruments, Hamden CT) on the stage of a dissecting microscope and impaled with microelectrodes under direct view. Steady-state currents achieved within 2–5 min following bath change or drug addition were measured with a Geneclamp 500 amplifier (Axon Instruments, Burlingame, CA) interfaced to a Dell computer with a Digidata 1322A interface (Axon). Data acquisition and analysis utilized pCLAMP 8.0 software (Axon). The voltage pulse protocol generated with the Clampex subroutine consisted of 20 mV steps (of 738 ms duration) from −100 mV to +40 mV or = 80 mV, starting from a holding potential of −30 mV. Bath resistance was minimized by the use of agar bridges filled with 3 M KCl, and a virtual ground circuit clamped bath potential to zero.

Standard recording bath solution (ND-93) was (in mM) 93.5 NaCl, 2 KCl, 5 HEPES, and 2.8 MgCl2, with pH 7.40. Occasional experiments as noted used ND-96. 5% CO2-equilibrated solutions contained 72 mM NaCl and 24 mM NaHCO3− without HEPES. In anion substitution experiments, 93.5 or 96 mM NaCl was replaced with 93.5 or 96 mM Na gluconate, Na isethionate, Na cyclamate, or with 62 or 64 mM Na2SO4 as indicated. In experiments with mouse ENaC coexpression, 93.5 mM NaCl was replaced with equimolar N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMDG) chloride.

In some experiments, current was recorded continuously while oocyte membrane potential was held at the clamp potentials of either −30 mV or −90 mV for up to 10 min or longer, during which time bath solutions were changed from ND-93 to sodium isethionate to ND-93.

Materials.

The fluorescent dye BCECF acetoxymethyl ester was obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Tetrodotoxin was obtained from Biomol International L.P. (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Na36Cl and 35S-sulfate and were purchased from ICN (Irvine, CA). 2,2′-Di-isothiocyanato-4,4′-stilbenedisulfonate (DIDS) was from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Niflumic acid was from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). All other materials were of analytical grade and obtained from either Sigma-Aldrich or Fisher Scientific (Springfield, NJ). Mouse Slc26a3/Dra cDNA in pcDNA3 was the kind gift of James Melvin (University of Rochester). Human SLC26A3/DRA cDNA in pBF was as described (10). Mouse ENaC α, β, γ subunit cDNAs in pBluescript SK- (6) were kind gifts of Tom Kleyman (University of Pittsburgh). The pH-insensitive rat ROMK1 mutant K80M (15) was the kind gift of Paul Welling (University of Maryland).

Statistics.

All values are reported as means ± SE. Data between two treatment groups were compared using a two-tailed unpaired Student t-test assuming equal variances between groups. Paired t-test was used to compare isotopic efflux into different bath solutions from individual oocytes. Data from multiple treatment groups were compared using a one-way analysis of variance with a post hoc Tukey's t-test. A probability value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Absence of Dra abolishes cecal Cl−/HCO3− exchange with minimal change in Isc.

Previous isotopic flux studies of murine small intestine found that loss of Cl− absorption in the Dra KO mouse was not associated with equivalent changes in the transepithelial Isc, suggesting that Dra-mediated Cl−/HCO3− exchange is electroneutral (43). However, it has been postulated that electroneutral Cl− absorption may result from simultaneous, tightly coupled electrogenic activities of Pat-1-mediated 1Cl−/2HCO3− exchange and Dra-mediated 2Cl−/1HCO3− exchange (32).

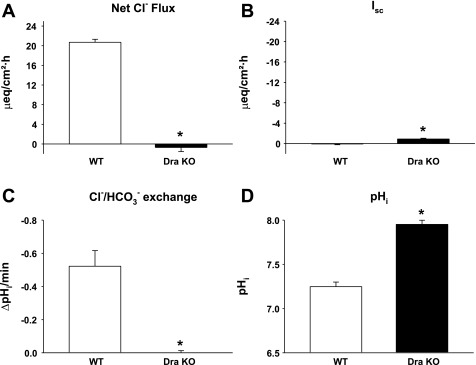

Murine cecal mucosa expresses Dra at high levels but Pat-1 transcripts in low abundance (1, 44). Using transepithelial 36Cl− isotopic fluxes, activity of Dra-mediated Cl−/HCO3− exchange in murine cecum was investigated. As shown in Fig. 1A, WT cecal mucosa shows robust net Cl− absorption under basal conditions whereas Cl− absorption is essentially absent in the Dra KO cecum. As observed in 36Cl− flux studies of murine small intestine (43), the Isc in the Dra KO cecum was slightly but significantly increased as compared with WT (Fig. 1B). However, the increase of ∼1 μeq·cm−2·h−1 did not match the ∼10 μeq·cm−2·h−1 predicted from measured net Cl− absorption for an exchange stoichiometry of 2Cl−/1HCO3−. Moreover, the elevated Isc was not likely associated with increased expression of Pat-1 or Cftr, since mRNA transcript levels of these transporters are unchanged in the Dra KO mouse intestine (43). To evaluate Cl−/HCO3− exchange at the apical membrane of the surface epithelium, BCECF microspectrofluorimetry measured the rate of change in pHi during luminal Cl− removal. As shown in Fig. 1C, Cl−-dependent ΔpHi/Δt showed strong alkalinization in WT which was absent in the Dra KO cecal surface epithelium under basal conditions. Similar to findings in duodenal villous epithelium of the Dra KO, the basal pHi in the Dra KO was significantly alkaline relative to WT surface epithelium (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Knockout of Dra abolishes cecal Cl−/HCO3− exchange with minimal change in short-circuit current (Isc). A: net 36Cl− flux across the cecal mucosa from wild-type (WT) and Dra knockout (KO) mice (n = 3 pairs). B: Isc measured during 36Cl− flux measurements of cecal mucosa from WT and Dra KO mice. C: Cl−/HCO3− exchange rates measured as change in intracellular pH per minute (ΔpHi/min) during removal of apical (luminal) Cl− in surface epithelium of cecal mucosa from WT and Dra KO mice (n = 4). D: pHi measured in balanced Krebs bicarbonate Ringer (KBR) solutions (n = 4). Values are means ± SE. *Significantly different from WT littermates.

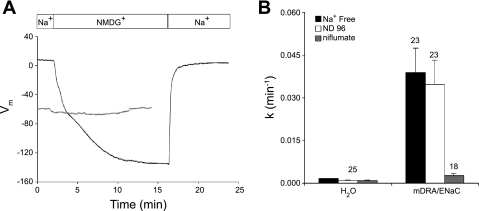

Absence of Dra does not alter Cl−-dependent regulation of cecal Va.

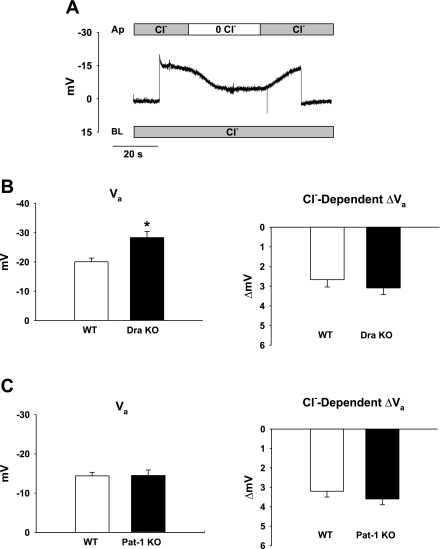

An electrogenic 2Cl−/1HCO3− exchange stoichiometry for Dra should depolarize the apical membrane potential (Va) of the surface epithelium during removal of luminal Cl− to induce exchange of intracellular Cl− for extracellular HCO3− (Cl−OUT/HCO3−IN exchange). Therefore, chloride-dependent changes in Va were investigated during sustained impalements of the surface epithelium using conventional microelectrodes. As shown by the experiment on WT cecal surface epithelium in Fig. 2A, intracellular recording is established by cell impalement during luminal superfusion with KBR containing 120 mM Cl−. During the impalement, a change in luminal superfusate to nominally Cl−-free KBR solution causes Va to depolarize. Following a switch back to luminal KBR, Va repolarizes. Initial microelectrode studies performed at room temperature (∼22°C) did not detect significant differences between WT and Dra KO cecal surface epithelium for basal Va prior to removal of luminal Cl− [WT Va = −20.4 ± 3.0 vs. Dra KO Va = −23.7 ± 3.2 mV, n = 3; not significant (NS)] or in the magnitude of the Cl−-dependent ΔVa (WT ΔVa = 5.4 ± 1.5 vs. Dra KO Va = 4.8 ± 0.7 mV, NS; not shown). Interestingly, basal Va in the Dra KO epithelium at 37°C was slightly hyperpolarized relative to WT (Fig. 2B). However, Cl−-dependent ΔVa did not differ between WT and Dra KO cecum. The observed hyperpolarization of basal Va (37°C) in the absence of Dra is the opposite of the depolarization predicted by loss of a 2Cl−/1HCO3− exchange process, and the lack of difference in Cl−-dependent ΔVa between WT and Dra KO cecum is consistent with electroneutral Cl−/HCO3− exchange. To determine whether the increased basal Va in the Dra KO at 37°C resulted from unmasking electrogenic activity of Pat-1 in the absence of Dra, microelectrode analysis was performed on Pat-1 KO cecal mucosa. However, as shown in Fig. 2C, no significant differences were found between WT and Pat-1 KO cecal epithelium in either basal Va or in Cl−-dependent ΔVa.

Fig. 2.

Absence of Dra does not alter Cl−-dependent regulation of apical membrane potential (Va) in cecal surface epithelium. A: conventional microelectrode recording of Va in WT cecal surface epithelium during removal and restoration of luminal Cl−. Representative of 14 impalements from 6 WT mice. Ap, apical; BL, basolateral. B: summary of initial Va (left) and maximal ΔVa during apical (luminal) Cl− substitution (right) of surface epithelium at 37°C in WT and Dra KO ceca (n = 11–14 impalements from 6 WT and Dra KO pairs). C: summary of initial Va (left) and maximal ΔVa during apical (luminal) Cl− substitution (right) of surface epithelium at 37°C in WT and putative anion transporter-1 (Pat-1) KO ceca (n = 15–18 impalements from 6 WT and Pat-1 KO pairs). Values are means ± SE. *Significantly different from WT littermates.

Cl−-dependent regulation of cecal Va requires expression of Cftr.

Since both WT and Dra KO cecal surface epithelium depolarized during luminal Cl− removal, we investigated whether Cl−-dependent depolarization of Va resulted from Cftr-mediated Cl− efflux during the imposed cell-to-lumen Cl− gradient. As shown by the experiment using Cftr KO cecum in Fig. 3A, removal of luminal Cl− during sustained impalement of the surface epithelium hyperpolarized Va, an effect opposite that observed in WT or Dra KO tissues. The observed hyperpolarization was not associated with changes in Dra or Pat-1 expression, since previous studies have shown that mRNA transcript levels of these transporters are unchanged in Cftr KO intestine (33). The cumulative data from these experiments (Fig. 3B) showed that Va hyperpolarized by ∼−10 mV as compared with ∼+3 mV depolarization in WT cecum, indicating that depolarization of Va is Cftr-dependent during luminal Cl− substitution. In the absence of Cftr, the observed Va hyperpolarization is contrary to the depolarization predicted for 2Cl−/1HCO3− exchange activity by Dra.

Fig. 3.

Chloride-dependent depolarization of cecal Va requires expression of Cftr. A: conventional microelectrode recording of Va in Cftr KO cecal surface epithelium during removal and restoration of apical (luminal) Cl−. Representative of 12 impalements from 6 Cftr KO mice. B: summary of maximal ΔVa during apical (luminal) Cl− substitution in WT, Cftr KO, Cftr KO bathed with 80 mM K+, and Dra/Cftr double-knockout (dKO) ceca (n = 14 impalements from 6 WT, 13 impalements from 6 Cftr KO, 12 impalements from 6 Cftr KO bathed in 80 mM K+ KBR, and 9 impalements from 4 Dra/Cftr dKO ceca). Values are means ± SE. #Significantly different from WT. *Significantly different from Cftr KO.

Luminal Cl− removal alkalinizes pHi in a Dra-dependent process (Fig. 1C). Since previous studies have shown that alkalinization of pHi in the surface epithelium of rabbit colon activates membrane K+ conductances (14), Va was recorded in Cftr KO cecum exposed to 80 mM extracellular K+ before and during luminal Cl− removal. As shown in Fig. 3B, depolarization by increased extracellular K+ prevented hyperpolarization in the Cftr KO cecal surface epithelium. To determine whether Va hyperpolarization in Cftr KO cecum during luminal Cl− removal was Dra-dependent, similar studies were performed in Cftr/Dra double KO cecum. As shown by the cumulative data in Fig. 3B, luminal Cl− removal during superfusion of the Cftr/Dra double KO cecum in KBR did not change Va. These findings indicate that induction of Dra-mediated Cl−OUT/HCO3−IN exchange hyperpolarizes Va, possibly a result of cell alkalinization activating a K+ conductance, and that this effect is dissipated by the presence of Cftr. Since basal Va was not hyperpolarized in the Cftr/Dra double KO epithelium (Cftr/Dra KO Va = −9.7 ± 1.5 mV, n = 4–6), the findings also raise the possibility that the small inward Isc detected in the Dra KO small and large intestine is secondary to increased Cftr-dependent Cl− secretion resulting from the activation of hyperpolarizing membrane K+ conductances by an alkaline pHi in the enterocytes. Alternatively, the small inward Isc (anion secretion or cation absorption) is normally suppressed by Dra expression.

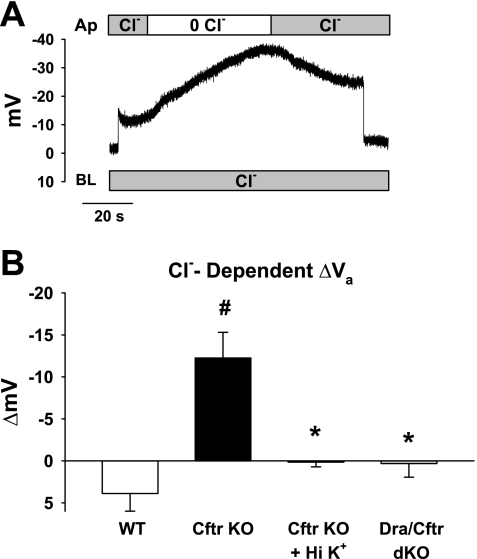

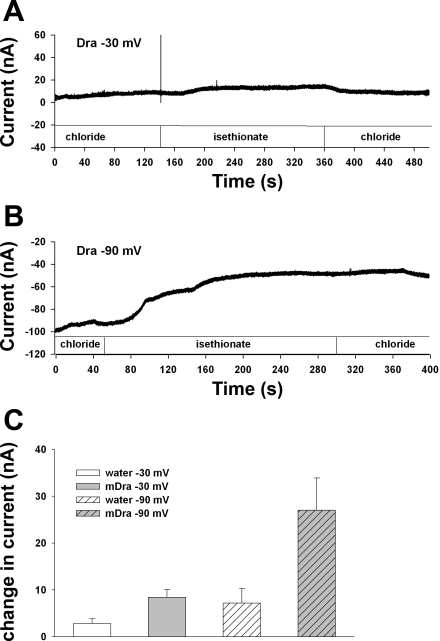

Dra-mediated exchange of intracellular Cl− for extracellular HCO3− in Xenopus oocytes is accompanied by slow hyperpolarization.

Resting membrane potential (Vm) for Dra-expressing Xenopus oocytes was −50 ± 2.9 mV (n = 6), as compared with −40 ± 3.3 mV in oocytes previously injected with water (Fig. 4, A and B, n = 4). This small hyperpolarized Vm itself is compatible with basal activity of Dra-mediated electrogenic 2Cl−/1HCO3− exchange. However, the stoichiometry of 2Cl−/1HCO3− predicts that initiation of Cl−/HCO3− exchange by extracellular Cl− removal should be accompanied by rapid depolarization. As shown in Fig. 4B in Xenopus oocytes expressing Dra, initiation of peak Cl−/HCO3− exchange rates by bath Cl− removal (JH+ = 1.04 ± 0.23 mM/min, n = 6) is accompanied instead by a slow hyperpolarization (peaking at −11.7 ± 1.9 mV after 10 min in Cl−-free bath, n = 6) that parallels increasing intracellular alkalinization. These patterns reflect those previously reported for human DRA (10).

Fig. 4.

Dra-mediated Cl−/HCO3− exchange initiated by extracellular Cl− removal from Xenopus oocytes is unaccompanied by depolarization. Vm, membrane potential. A: pH-sensitive microelectrode recording of Cl−/HCO3− exchange in a Xenopus oocyte previously injected with water, recorded during bath Cl− removal and restoration. Top: voltage trace vs. time. Bottom: pHi trace vs. time. Representative of 4 water-injected oocytes. B: pH-sensitive microelectrode recording of Cl−/HCO3− exchange in oocyte expressing mSlc26a3/Dra, recorded during bath Cl− removal and restoration. Top: voltage trace vs. time. Bottom: pHi trace vs. time. Representative of 6 mSlc26a3-expressing oocytes.

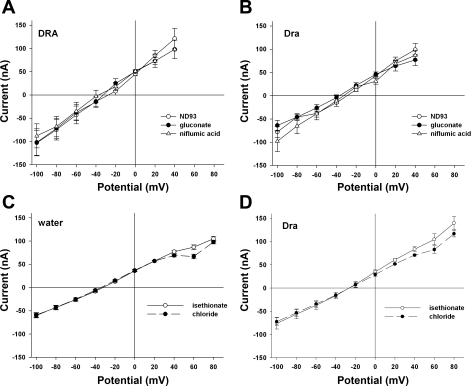

Dra-mediated Cl−/OH− and Cl−/HCO3− exchange activities are unaccompanied by Cl−-dependent changes in steady-state currents in Xenopus oocytes.

A stoichiometry of 2Cl−/1HCO3− exchange for Dra predicts that, at membrane potentials negative to resting Em, initiation of Cl−/HCO3− exchange by extracellular Cl− removal should be accompanied by a steady-state inward current. Fig. 5 shows, in contrast, that neither Cl−/OH− exchange nor Cl−/HCO3− exchange in Dra-expressing Xenopus oocytes is accompanied by detectable steady-state current as measured by two-electrode voltage clamp. The results were similar when cyclamate was used as substituting anion rather than gluconate or isethionate (Supplemental Fig. S1; Supplemental Material for this article is available online at the Journal website). In contrast, similar oocytes in room air exhibited robust bath Cl−-dependent 36Cl− efflux activity (Supplemental Fig. S1), accompanied by 36Cl− influx activity of 8.13 ± 1.1 nmol·oocyte−1·h−1 (n = 8, not shown). This rate of influx predicts, for an exchange stoichiometry of 2Cl−:1OH−, a bath Cl−-dependent component of steady-state current of 250 nA at Vm = −50 mV. In contrast, Fig. 5B reveals in Dra-expressing oocytes a Cl−-difference current at −50 mV of ∼10 nA. The JH+ of 1.04 mM/min in the presence of HCO3− (Fig. 4B) predicts at −62 mV a steady-state inward current of 471–750 nA, assuming oocyte Cl− space between 285 nl (32) and 450 nl (7). But Dra-expressing oocytes reveal no detectable Cl−/HCO3− exchange current at inside negative potentials (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Dra-mediated Cl−/OH− and Cl−/HCO3− exchanges are unaccompanied by Cl−-dependent currents. Two-electrode voltage clamp current-voltage relationships of Xenopus oocytes previously injected with cRNA encoding hSLC26A3/DRA (A) or mSlc26a3/Dra (B), recorded in room air during sequential exposures to baths containing Cl− (ND-93), gluconate substitute, and Cl− in the presence of the DRA inhibitor, niflumic acid. Current-voltage relationships of oocytes previously injected with water (C) or with cRNA encoding mSlc26a3/Dra (D), recorded in 5% CO2/24 mM HCO3− during sequential exposures to baths containing isethionate and Cl−. Values are means ± SE; n = 5 for each condition.

Dra-mediated Cl−/HCO3− exchange is accompanied by the delayed onset of modest outward current in Xenopus oocytes.

The steady-state currents of Fig. 5 might in principle reflect the sum of a rapidly activated inward exchange current and a slowly activated compensatory outward current mediated by a native conductance of the oocyte. We therefore recorded time-dependent currents during bath Cl− removal and restoration at two clamped holding potentials of −30 and −90 mV (Fig. 6). The exchange stoichiometry of 2Cl−/1HCO3− predicts that initiation of Dra-mediated Cl−/HCO3− exchange by bath Cl− removal should be accompanied by rapid onset inward current. In contrast, exchange was accompanied by small voltage-dependent outward currents with onset evident only 40–60 s after initiation of anion exchange. Peak Dra-associated Cl− removal-dependent outward current was ∼5 nA at −30 mV and ∼20 nA at −90 mV. Upon bath Cl− restoration, the outward current decreased very slowly, in contrast to the rapid reversal of Cl−/HCO3− exchange and accompanying intracellular acidification (Fig. 4B). Thus, monitoring of time-dependent current does not support the hypothesis that Dra-mediated, rapid-onset inward current is masked at steady state by an endogenous outward current of equal magnitude.

Fig. 6.

Dra-mediated Cl−/HCO3− exchange triggered by bath Cl− removal under voltage clamp is not accompanied by inward current. Current measured in representative Xenopus oocytes expressing mSlc26a3/Dra while clamped at −30 mV (A) or at −90 mV (B) during sequential exposures to baths containing Cl−, isethionate substitute, and Cl−. C: summary of peak change in current elicited by bath substitution from Cl− to isethionate; summarized data from 5 oocytes previously injected with water, and from 9 oocytes expressing mSlc26a3/Dra, clamped at −30 mV or at −90 mV. Values are means ± SE.

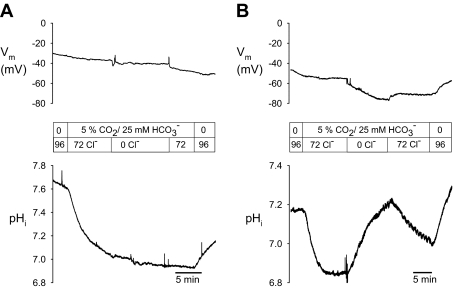

Dra-mediated 36Cl− efflux is voltage-insensitive in oocytes coexpressing ENaC or ROMK.

To provide another index of voltage-dependence of Dra, we coexpressed Dra in Xenopus oocytes (Fig. 7A) with (black trace) or without (gray trace) the mouse αβγENaC epithelial Na+ channel. In these oocytes, bath Na+ replacement with NMDG reversibly hyperpolarized Vm from +8 ± 3 mV to −78 ± 3 mV within 2 min (n = 4), and to −137 ± 3 mV within 15 min (n = 3). Similar hyperpolarization was noted in oocytes expressing ENaC alone (n = 5, not shown), but not in oocytes expressing Dra alone (gray trace and Fig. 4B). Figure 7B shows that the rate of mDRA-mediated 36Cl− efflux from ENaC-expressing oocytes was insensitive to this substantial hyperpolarization, but remained sensitive to inhibition by the Dra inhibitor, niflumate (10). We also coexpressed mDRA with the pHi-insensitive K80M mutant of rat ROMK1, under conditions in which bath Na+ replacement with K+ depolarized oocytes from −55 + 10 mV to −11 + 1 mV (n = 8). Upon such depolarization by high bath K+, the rate of Dra-mediated 36Cl− efflux was similarly insensitive to membrane potential (n = 8, not shown).

Fig. 7.

Dra-mediated 36Cl− efflux in room air is not sensitive to human epithelial Na+ channel (hENaC)-dependent changes in Vm. A: Vm recordings from representative Xenopus oocytes coexpressing Dra with (black trace) or without (level gray trace) mouse ENaC α/β/γ, during sequential exposure to baths containing Na+, N-methyl-d-glucamine (NMDG), and again Na+. One of 4 similar experiments. B: 36Cl− efflux rate constants of oocytes previously injected with water or coinjected with cRNA encoding Dra and mouse ENaC α/β/γ, and sequentially exposed to bath solutions containing first NMDG (Na+-free), then Na+ (ND-96), and finally Na+ plus Dra inhibitor niflumate (100 μM). Values are means ± SE (n as indicated).

The protocol examining the effect on Dra-mediated Cl−/HCO3− exchange of Vm changes induced by coexpressed cation channel activity was validated using the conditionally electrogenic mutant E699Q of the mouse Slc4a1/Ae1 Cl−/HCO3− exchanger (8). Mouse Ae1 E699Q mediates electroneutral sulfate/sulfate exchange, but electrogenic exchange of intracellular sulfate for bath Cl−. In oocytes coexpressing ENaC with mAe1 E699Q, the rate constant of electroneutral sulfate efflux into bath sulfate was bath Na+-independent (Supplemental Fig. S2A). In contrast, the rate constant of sulfate efflux into bath Cl−, representing electrogenic sulfate/Cl− exchange, was strongly accelerated by the hyperpolarization associated with bath Na+ removal (Supplemental Fig. S2B).

DISCUSSION

The present study supports the hypothesis that murine and human orthologs of Dra exhibit electroneutral Cl−/HCO3− exchange consistent with a symmetrical transport stoichiometry (e.g., 1Cl−/1HCO3− or 2Cl−/2HCO3− exchange). Several lines of evidence support this conclusion. First, the magnitude of Va changes in mouse cecum surface epithelium during luminal Cl− substitution was similar in the presence or absence of endogenous Dra. Moreover, Cl−-dependent ΔVa in WT and Pat-1 KO ceca was similarly indistinguishable, indicating that the absence of endogenous Dra-dependent effects on ΔVa does not result from equal and opposite anion exchange stoichiometries for Dra and Pat-1. Second, a 2Cl−/1HCO3− exchange stoichiometry predicts that the observed Dra-dependent component of net cecal Cl− absorption of ∼20 μeq·cm−2·h−1 should generate an outward current of ∼10 μeq·cm−2·h−1. However, WT cecal Isc was near zero, and Isc across Dra KO cecum increased in an inward direction by only ∼1 μeq·cm−2·h−1. Values of Dra-dependent Cl− absorption and Isc not easily explained by electrogenic 2Cl−/1HCO3− exchange have also been reported in the small intestine (43). Third, murine and human Dra expressed in Xenopus oocytes exhibited no appreciable increments in steady-state current during induction of Cl−/OH− or Cl−/HCO3− exchange. In contrast, a stoichiometry of 2Cl−/1HCO3−(OH−) predicts that a steady-state current of >250 nA at inside negative potentials should accompany the observed rates of Dra/DRA-dependent 36Cl− efflux [Supplemental Fig. S1 (10)] and Cl−/HCO3− exchange (Fig. 4). Fourth, Dra-mediated 36Cl− efflux from oocytes coexpressing either ENaC or pHi-insensitive ROMK channels was not affected by pronounced depolarization or hyperpolarization of Vm induced by bath cation substitution.

Although the above combined data do not support a 2Cl−/1HCO3− exchange stoichiometry for Dra, the expression of either endogenous or recombinant Dra is nonetheless associated with changes in cell membrane potential. Similar to Dra KO small intestine (43), the Dra KO cecum under basal conditions exhibited slightly greater Isc and more hyperpolarized Va than did WT cecum. Moreover, in the absence of Cftr (i.e., Cftr KO cecum), induction of Cl−OUT/HCO3−IN exchange by luminal Cl− substitution hyperpolarized Va by a Dra-dependent process. These responses, opposite to those predicted for 2Cl−/1HCO3− exchange, may reflect, among other possibilities, cell alkalinization-induced activation of membrane K+ conductances. Microelectrode analysis of the surface epithelium of rabbit colon has shown that cell alkalinization induced by either luminal Cl− removal or reducing CO2 potently activates K+ conductances in both apical and basolateral membranes (14), possibly by increasing the Ca2+i-sensitivity of large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels (21). If this relationship holds in mouse large intestine, the alkaline pHi of surface epithelium in Dra KO cecum (Fig. 1D) would increase basolateral K+ channel activity, resulting in increased Va and Isc under basal conditions. Induction of Dra-mediated HCO3− influx in the Cftr KO cecum would also be accompanied by Va hyperpolarization, since the epithelium lacks a major apical Cl− conductance to relax Va during luminal Cl− substitution. In support of this hypothesis, preliminary studies indicate that increased baseline Isc in Dra KO small intestine is eliminated by epithelial acidification induced by reducing luminal pH and [HCO3−] (data not shown). However, additional studies will be necessary to determine the ionic basis of the small Isc in the Dra KO intestine and whether this phenomenon is a normal physiological entity or a compensatory change resulting from Dra ablation.

Expression of murine Dra in Xenopus oocytes was accompanied by Vm hyperpolarization under basal conditions and during removal of extracellular Cl− to induce Cl−OUT/HCO3−IN exchange. Although hyperpolarization of resting Vm by Dra expression is predicted by electrogenic 2Cl−/1HCO3− exchange, such hyperpolarization of resting Vm has not been consistently observed in other studies. Previous investigations of human DRA and murine Dra expression in oocytes showed either no change or rapid depolarization of resting Vm (10, 32), suggesting that resting Vm in Dra/DRA-expressing oocytes may not be a reliable index of transporter electrogenicity. In the current study, induction of Dra-mediated Cl−OUT/HCO3−IN exchange by extracellular Cl− removal was associated with slow hyperpolarization of oocyte Vm and small outward current activity (Figs. 4B and 6), opposite to changes predicted by 2Cl−/1HCO3− exchange stoichiometry. Extracellular Cl− removal produces a similar effect on Vm in oocytes expressing human DRA (10). Hyperpolarization of Vm during Cl− substitution was paralleled by increasing oocyte pHi, suggesting that, as in cecal epithelium, Dra-dependent intracellular alkalinization may affect native (K+) conductances. The minimal outward current measured at −30 mV holding potential in Dra-expressing oocytes during Cl− substitution paradoxically increased slightly (∼30 nA), though not significantly, at a −90 mV holding potential.

The Vm hyperpolarization observed upon induction of Cl−OUT/(OH−)HCO3−IN exchange in Dra-expressing oocytes contrasts with a previous study showing rapid depolarization of Vm during Cl− substitution in Dra-expressing oocytes (32). That study demonstrated with Cl−- and H+-sensing microelectrodes that murine Dra expressed in oocytes exhibits an exchange flux ratio of ∼2Cl−:1HCO3− and, in the presence of nitrate or thiocyanate, also mediates uncoupled anion currents. However, all reported rates of Dra-mediated coupled exchange flux in oocyte expression systems are an order of magnitude or more slower than rates typically measured in mammalian tissue or in mammalian cell culture expression systems (18, 34, 42) and may thus be more susceptible to distortion by minor anion conductances. The different Vm responses to bath Cl− substitution between the present and earlier oocyte expression studies also raise questions about possible differences in levels of heterologous protein overexpression, variability in levels of endogenous transporter activities, and other potentially relevant experimental conditions. In common to all studies, however, was evidence that Cl−/(OH−)HCO3− exchange activity in Dra-expressing oocytes does not closely correlate with changes in Vm. In the present study, induction of Cl−OUT/HCO3−IN exchange by Cl− removal was associated with a delayed, slow hyperpolarization of Vm. In contrast, the rate and extent of oocyte Vm depolarization during extracellular Cl− substitution in an earlier study was greater in the absence of HCO3− (i.e., during Cl−/OH− exchange) than in its presence, whereas Cl−/HCO3− exchange rates were 5–10 times greater than those for Cl−/OH− exchange (32). This dissociation of Dra-mediated Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity from changes in Vm during Cl− substitution constitutes another inconsistency with an exchange stoichiometry of 2Cl−/1HCO3−.

In summary, endogenous Dra in the surface epithelium of murine cecum dominates Cl−/HCO3− exchange activity, but does not affect the apical membrane potential during induction of Cl−OUT/HCO3−IN exchange. The apparent electroneutrality of Dra-mediated exchange was not due to equal and opposite coupling stoichiometry with Pat-1, as shown by similar responses in the Pat-1 KO cecal epithelium. Electroneutral anion exchange by Dra alone, rather than precisely additive coupling of Dra and Pat-1, is also consonant with known differences in the expression patterns of Dra and Pat-1 along the longitudinal axis of the intestine (1, 25, 45) and with the reciprocal Dra and Pat-1 expression patterns along the crypt-villus axis (16). The small inward Isc under basal conditions in the Dra KO cecum did not correlate with changes in Cl− absorption. Rather, the inward Isc may reflect increased activity of basolateral K+ channels secondary to the higher resting pHi in Dra KO epithelium (14). Earlier studies of Dra/DRA expressed in transient, stable, and inducible mammalian cell systems also support electroneutrality of Dra activity in showing that Cl−/(OH−)HCO3− exchange rate is unaffected by membrane depolarization with high external [K+] (18, 24, 25). The lack of correlation between Dra-mediated Cl−/HCO3− exchange and electrogenic activity in murine cecum and our in vitro expression system may not apply to other tissues where Cftr and Dra are coexpressed. Others' data supporting electrogenicity of Dra overexpressed in Xenopus oocytes and mammalian cells have been cited to explain the high concentration of HCO3− in the distal pancreatic duct (23). However, recent mammalian cell studies suggest that high rates of HCO3− secretion in distal pancreatic duct may instead result from increased HCO3− permeability of Cftr and inhibition of Dra Cl−/HCO3− exchange through the activation of Cl−-sensing with-no-lysine kinases (e.g., Wnk1) (28).

We conclude, in the context of endogenous expression levels and apical membrane potential of mouse cecum, that Dra/DRA activity exhibits high rates of electroneutral 1Cl−/1HCO3− exchange which may have indirect effects on electrogenic transporters, at least in part through regulation of [Cl−]i and pHi. Thus, the participation of Dra-mediated Cl−/HCO3− exchange in coupled NaCl absorption and in uncoupled HCO3− secretion is consistent with the classical concept that these processes are electroneutral, and remain useful paradigms for predicting epithelial responses in health and disease.

GRANTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (DK48816 to L. L. Clarke; DK43495 to S. L. Alper) and the Harvard Digestive Diseases Center DK34854. A. K. Stewart was supported by a Pilot/Feasibility Grant from the Harvard Digestive Diseases Center DK34854.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1. Alrefai WA, Wen X, Jiang W, Katz JP, Steinbrecher KA, Cohen MB, Williams IR, Dudeja PK, Wu GD. Molecular cloning and promoter analysis of downregulated in adenoma (DRA). Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 293: G923–G934, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barone S, Amlal H, Xu J, Kujala M, Kere J, Petrovic S, Soleimani M. Differential regulation of basolateral Cl−/HCO3− exchangers SLC26A7 and AE1 in kidney outer medullary collecting duct. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 2002–2011, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Borenshtein D, Fry RC, Groff EB, Nambiar PR, Carey VJ, Fox JG, Schauer DB. Diarrhea as a cause of mortality in a mouse model of infectious colitis. Genome Biol 9: R122, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Borenshtein D, Schlieper KA, Rickman BH, Chapman JM, Schweinfest CW, Fox JG, Schauer DB. Decreased expression of colonic Slc26a3 and carbonic anhydrase IV as a cause of fatal infectious diarrhea in mice. Infect Immun 77: 3639–3650, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bukhave K, Rask-Madsen J. Saturation kinetics applied to in vitro effects of low prostaglandin E2 and F2α concentrations on ion transport across human jejunal mucosa. Gastroenterology 78: 32–42, 1980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Carattino MD, Hill WG, Kleyman TR. Arachidonic acid regulates surface expression of epithelial sodium channels. J Biol Chem 278: 36202–36213, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chernova MN, Humphreys BD, Robinson DH, Stuart-Tilley A, Garcia AM, Brosius FC, Alper SL. Functional consequences of mutations in the transmembrane domain and the carboxy-terminus of the murine AE1 anion exchanger. Biochim Biophys Acta 1329: 111–123, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chernova MN, Jiang L, Crest M, Hand M, Vandorpe DH, Strange K, Alper SL. Electrogenic sulfate/chloride exchange in Xenopus oocytes mediated by murine AE1 E699Q. J Gen Physiol 109: 345–360, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chernova MN, Jiang L, Friedman DJ, Darman RB, Lohi H, Kere J, Vandorpe DH, Alper SL. Functional comparison of mouse slc26a6 anion exchanger with human SLC26A6 polypeptide variants: differences in anion selectivity, regulation, and electrogenicity. J Biol Chem 280: 8564–8580, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chernova MN, Jiang L, Shmukler BE, Schweinfest CW, Blanco P, Freedman SD, Stewart AK, Alper SL. Acute regulation of the SLC26A3 congenital chloride diarrhoea anion exchanger (DRA) expressed in Xenopus oocytes. J Physiol 549: 3–19, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Clarke LL, Boucher RC. Chloride secretory response to extracellular ATP in human normal and cystic fibrosis nasal epithelia. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 263: C328–C356, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Clarke LL, Harline MC. CFTR is required for cAMP inhibition of intestinal Na+ absorption in a cystic fibrosis mouse model. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 270: G259–G267, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Donowitz M, Welsh MJ. Regulation of mammalian small intestinal electrolyte secretion. In: Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract, edited by Johnson LR. New York: Raven Press, 1987, p. 1351–1388 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Duffey ME, Devor DC. Intracellular pH and membrane potassium conductance in rabbit distal colon. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 258: C336–C343, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fakler B, Schultz JH, Yang J, Schulte U, Brandle U, Zenner HP, Jan LY, Ruppersberg JP. Identification of a titratable lysine residue that determines sensitivity of kidney potassium channels (ROMK) to intracellular pH. EMBO J 15: 4093–4099, 1996 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gawenis LR, Franklin CL, Simpson JE, Palmer BA, Walker NM, Wiggins TM, Clarke LL. cAMP inhibition of murine intestinal Na+/H+ exchange requires CFTR-mediated cell shrinkage of villus epithelium. Gastroenterology 125: 1148–1163, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gill RK, Borthakur A, Hodges K, Turner JR, Clayburgh DR, Saksena S, Zaheer A, Ramaswamy K, Hecht G, Dudeja PK. Mechanism underlying inhibition of intestinal apical Cl−/OH− exchange following infection with enteropathogenic E. coli. J Clin Invest 117: 428–437, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hayashi H, Suruga K, Yamashita Y. Regulation of intestinal Cl−/HCO3− exchanger SLC26A3 by intracellular pH. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 296: C1279–C1290, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jiang Z, Grichtchenko II, Boron WF, Aronson PS. Specificity of anion exchange mediated by mouse Slc26a6. J Biol Chem 277: 33963–33967, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kere J, Lohi H, Hoglund P. Genetic disorders of membrane transport. III. Congenital chloride diarrhea. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 276: G7–G13, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Klaerke DA, Wiener H, Zeuthen T, Jorgensen PL. Ca2+ activation and pH dependence of a maxi K+ channel from rabbit distal colon epithelium. J Membr Biol 136: 9–21, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ko SBH, Shcheynikov N, Choi JY, Luo X, Oshibashi K, Thomas PJ, Kim JY, Kim KH, Lee MG, Naruse S, Muallem S. A molecular mechanism for aberrant CFTR-dependent HCO3− transport in cystic fibrosis. EMBO J 21: 5662–5672, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ko SBH, Zeng W, Dorwart MR, Luo X, Kim KH, Millen L, Goto H, Naruse S, Soyombo A, Thomas PJ, Muallem S. Gating of CFTR by the STAS domain of SLC26 transporters. Nat Cell Biol 6: 343–350, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lamprecht G, Baisch S, Schoenleber E, Gregor M. Transport properties of the human intestinal anion exchanger DRA (down-regulated in adenoma) in transfected HEK293 cells. Pflügers Arch 449: 479–490, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Melvin JE, Park K, Richardson L, Schultheis PJ, Shull GE. Mouse down-regulated in adenoma (DRA) is an intestinal Cl−/HCO3− exchanger and is up-regulated in colon of mice lacking the NHE3 Na+/H+ exchanger. J Biol Chem 274: 22855–22861, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Musch MW, Arvans DL, Wu GD, Chang EB. Functional coupling of the downregulated in adenoma Cl−/base exchanger DRA and the apical Na+/H+ exchangers NHE2 and NHE3. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 296: G203–G210, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ohana E, Yang D, Shcheynikov N, Muallem S. Diverse transport modes by the solute carrier 26 family of anion transporters. J Physiol 587: 2179–2185, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Park HW, Nam JH, Kim JY, Namkung W, Yoon JS, Lee JS, Kim KS, Venglovecz V, Gray MA, Kim KH, Lee MG. Dynamic regulation of CFTR bicarbonate permeability by [Cl−]i and its role in pancreatic bicarbonate secretion. Gastroenterology 139: 620–631, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Powell DW. Intestinal water and electrolyte transport. In: Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract, edited by Johnson LR. New York: Raven Press, 1987, p. 1267–1306 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Raheja G, Singh V, Ma K, Boumendjel R, Borthakur A, Gill RK, Saksena S, Alrefai WA, Ramaswamy K, Dudeja PK. Lactobacillus acidophilus stimulates the expression of SLC26A3 via a transcriptional mechanism. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 298: G395–G401, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schweinfest CW, Spyropoulos DD, Henderson KW, Kim JH, Chapman JM, Barone S, Worrell RT, Wang Z, Soleimani M. slc26a3 (dra)-deficient mice display chloride-losing diarrhea, enhanced colonic proliferation, and distinct up-regulation of ion transporters in the colon. J Biol Chem 281: 37962–37971, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shcheynikov N, Wang Y, Park M, Ko SBH, Dorwart M, Naruse S, Thomas PJ, Muallem S. Coupling modes and stoichiometry of Cl−/HCO3− exchange by slc26a3 and slc26a6. J Gen Physiol 127: 511–524, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Simpson JE, Gawenis LR, Walker NM, Boyle KT, Clarke LL. Chloride conductance of CFTR facilitates Cl−/HCO3− exchange in the villous epithelium of intact murine duodenum. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 288: G1241–G1251, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Simpson JE, Schweinfest CW, Shull GE, Gawenis LR, Walker NM, Boyle KT, Soleimani M, Clarke LL. PAT-1 (Slc26a6) is the predominant apical membrane Cl−/HCO3− exchanger in the upper villous epithelium of the murine duodenum. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 292: G1079–G1088, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Snouwaert JN, Brigman KK, Latour AM, Malouf NN, Boucher RC, Smithies O, Koller BH. An animal model for cystic fibrosis made by gene targeting. Science 257: 1083–1088, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stewart AK, Chernova MN, Kunes YZ, Alper SL. Regulation of AE2 anion exchanger by intracellular pH: critical regions of the NH2-terminal cytoplasmic domain. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 281: C1344–C1354, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stewart AK, Chernova MN, Shmukler BE, Wilhelm S, Alper SL. Regulation of AE2-mediated Cl− transport by intracellular or by extracellular pH requires highly conserved amino acid residues of the AE2 NH2-terminal cytoplasmic domain. J Gen Physiol 120: 707–722, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stewart AK, Shmukler BE, Vandorpe DH, Alper SL. Molecular characterization of Slc26a3 and Slc26a6 anion transporters in guinea pig pancreatic duct. J Med Invest 56, Suppl, 329–331, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Talbot C, Lytle C. Segregation of Na/H exchanger-3 and Cl/HCO3 exchanger SLC26A3 (DRA) in rodent cecum and colon. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 299: G358–G367, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Thomas JA, Buchsbaum RN, Zimniak A, Racker E. Intracellular pH measurements in ehrlich ascites tumor cells utilizing spectroscopic probes generated in situ. Biochemistry 18: 2210–2218, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Turnberg LA, Bieberdorf FA, Morawski SG, Fordtran JS. Interrelationship of chloride, bicarbonate, sodium and hydrogen transport in human ileum. J Clin Invest 49: 557–567, 1970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Walker NM, Simpson JE, Brazill JM, Gill RK, Dudeja PK, Schweinfest CW, Clarke LL. Role of down-regulated in adenoma anion exchanger in HCO3− secretion across murine duodenum. Gastroenterology 136: 893–901, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Walker NM, Simpson JE, Yen PF, Gill RK, Rigsby EV, Brazill JM, Dudeja PK, Schweinfest CW, Clarke LL. Down-regulated in adenoma Cl−/HCO3− exchanger couples with Na+/H+ exchanger 3 for NaCl absorption in murine small intestine. Gastroenterology 135: 1645–1653, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wang Z, Wang T, Petrovic S, Tuo B, Riederer B, Barone S, Lorenz JN, Seidler U, Aronson PS, Soleimani M. Renal and intestine transport defects in Slc26a6-null mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 288: C957–C965, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang ZH, Petrovic S, Mann E, Soleimani M. Identification of an apical Cl−/HCO3− exchanger in the small intestine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 282: G573–G579, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Xie Q, Welch R, Mercado A, Romero MF, Mount DB. Molecular characterization of the murine Slc26a6 anion exchanger: functional comparison with Slc26a1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283: F826–F838, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Xu J, Henriksnas J, Barone S, Witte D, Shull GE, Forte JG, Holm L, Soleimani M. SLC26A9 is expressed in gastric surface epithelial cells, mediates Cl−/HCO3− exchange, and is inhibited by NH4+. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 289: C493–C505, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Xu J, Song P, Miller ML, Borgese F, Barone S, Riederer B, Wang Z, Alper SL, Forte JG, Shull GE, Ehrenfeld J, Seidler U, Soleimani M. Deletion of the chloride transporter Slc26a9 causes loss of tubulovesicles in parietal cells and impairs acid secretion in the stomach. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 17955–17960, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yang H, Jiang W, Furth EE, Wen X, Katz JP, Sellon RK, Silberg DG, Antalis TM, Schweinfest CW, Wu GD. Intestinal inflammation reduces expression of DRA, a transporter responsible for congenital chloride diarrhea. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 275: G1445–G1453, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.