Abstract

Fasting in vivo and nutrient deprivation in vitro enhance sequestration of mitochondria and other organelles by autophagy for recycling of essential nutrients. Here our goal was to use a transgenic mouse strain expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) fused to rat microtubule-associated protein-1 light chain 3 (LC3), a marker protein for autophagy, to characterize the dynamics of mitochondrial turnover by autophagy (mitophagy) in hepatocytes during nutrient deprivation. In complete growth medium, GFP-LC3 fluorescence was distributed diffusely in the cytosol and incorporated in mostly small (0.2–0.3 μm) patches in proximity to mitochondria, which likely represent preautophagic structures (PAS). After nutrient deprivation plus 1 μM glucagon to simulate fasting, PAS grew into green cups (phagophores) and then rings (autophagosomes) that enveloped individual mitochondria, a process that was blocked by 3-methyladenine. Autophagic sequestration of mitochondria took place in 6.5 ± 0.4 min and often occurred coordinately with mitochondrial fission. After ring formation and apparent sequestration, mitochondria depolarized in 11.8 ± 1.4 min, as indicated by loss of tetramethylrhodamine methylester fluorescence. After ring formation, LysoTracker Red uptake, a marker of acidification, occurred gradually, becoming fully evident at 9.9 ± 1.9 min of ring formation. After acidification, GFP-LC3 fluorescence dispersed. PicoGreen labeling of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) showed that mtDNA was also sequestered and degraded in autophagosomes. Overall, the results indicate that PAS serve as nucleation sites for mitophagy in hepatocytes during nutrient deprivation. After autophagosome formation, mitochondrial depolarization and vesicular acidification occur, and mitochondrial contents, including mtDNA, are degraded.

Keywords: mitochondria, mitochondrial DNA, mitochondrial fission, mitophagosomes, mitophagy, preautophagic structures

autophagy refers to “self-eating” where cells degrade their cellular constituents to maintain cellular homeostasis as a normal response to stresses like starvation and in pathological conditions, including cancer, muscular disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, and pathogen infections (reviewed in Ref. 26). Glucagon released from the pancreas during fasting promotes hepatic autophagy, whereas insulin released after feeding suppresses autophagy (1, 50). Autophagy salvages amino acids, fatty acids, and other molecular building blocks essential for cell survival during nutrient deprivation. Autophagy also removes protein aggregates and unwanted or dysfunctional organelles, such as mitochondria. Prompt elimination of aged, damaged, and dysfunctional mitochondria may be important to protect cells against release of proapoptotic mitochondrial proteins, mitochondrial formation of toxic reactive oxygen species (ROS), and futile hydrolysis of ATP after uncoupling (24, 26, 48).

The term mitophagy has been introduced to describe autophagic degradation of mitochondria (24), and mitophagy is the predominant mechanism to remove superfluous and damaged mitochondria. In nonproliferating tissues like heart, brain, liver, and kidney, mitochondria turn over with a half-life of 10 to 25 days (25). Although some studies support the conclusion that autophagy, including mitophagy, occurs randomly (37), other evidence supports the concept that autophagy of mitochondria and other organelles occurs selectively. In yeast grown on methanol as a carbon source, peroxisomes proliferate. Changing the nutrient broth to glucose- or ethanol-containing medium results in specific degradation of peroxisomes by autophagy, a selective process termed pexophagy (17). Peroxin 14 is required for recognition of peroxisomes for such pexophagy (5). Similarly, withdrawal of treatment of hepatocytes with diethylhexylphthalate, a peroxisome proliferator, in the presence of protease inhibitors leads to accumulation of peroxisomes in autophagosomes, indicating selective pexophagy in mammalian cells (49).

During the postnatal period, glycogen is selectively sequestered into autophagosomes to enhance glycolytic substrate generation after interruption of transplacental nutrition (23). Autophagosomes formed postnatally contain large amounts of glycogen and rarely contain mitochondria or other organelles (21). After fasting or glucagon treatment, different cytoplasmic components were found at different times in autophagosomes, indicating ordered organelle degradation (22). In MCF-7 cells, mitophagy was induced after 30 h whereas ribosomal autophagy was dominant after 12 h of nutrient deprivation. In addition, in Uth1p deficient yeast, nutrient deprivation stimulates normal autophagy of various organelles but not mitochondria (19). However, a corresponding mammalian protein is yet to be identified. Additionally, mutation of Aup1, which is a mitochondrial phosphatase homologue localized to mitochondrial intermembrane space, decreases mitophagy in yeast (40). Parkin, BNIP3, and Atg32 are also implicated in targeting mitochondria for autophagy (15, 28, 29, 41, 51). Other work indicates that the mitochondrial permeability transition is involved in targeting mitochondria for autophagy (8, 33, 34). Taken together, these studies indicate that autophagy selectively targets different organelles in response to various stimuli and stresses.

During autophagy, phagophores (also called isolation membranes) of unknown origin form that sequester and enclose components of the cytoplasm to yield double-membrane vesicles called autophagosomes (36). Subsequently, autophagosomes fuse with late endosomes and/or lysosomes to mature into autolysosomes where degradation by lysosomal hydrolases occurs. The process of autophagy requires several evolutionarily conserved Atg (autophagy-related) proteins (47). Microtubule-associated protein-1 light chain 3 (LC3) is a mammalian homologue of yeast Atg8. Atg4B proteolytically cleaves the COOH terminus of proLC3 (LC3) to form LC3 I. Atg7 and Atg3 act to conjugate LC3 I with phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) to form LC3 II, which is recruited to forming autophagosomes (14). LC3 II remains on autophagosomes until after autophagosomal fusion with lysosomes occurs. Subsequently, LC3 II entrapped inside autophagosomes becomes degraded, whereas surface LC3 II is released and presumably recycled.

Although mammalian mitochondria are constantly renewed in nondividing cells, such as the hepatocytes of normal liver, the kinetics of mitophagy are not well characterized. Here, using hepatocytes isolated from green fluorescent protein (GFP)-LC3 transgenic mice, we show that preautophagosomal structures (PAS) serve as nucleation sites in mitophagy. Individual PAS grow to envelop and sequester whole or a part of polarized mitochondria into autophagosomes. Subsequent processing leads to vesicular acidification and degradation of mitochondrial contents, including mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Collagenase A was obtained from Roche (Penzberg, Germany); 3-methyladenine (3MA), protease cocktail, and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO); LysoTracker Red (LTR), MitoFluor Far Red (MFFR), tetramethylrhodamine methylester (TMRM), and PicoGreen from Molecular Probes (Carlsbad, CA); bicinchoninic acid (BCA) reagents from Pierce (Rockford, IL); 4%-12% Bis-Tris gels from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA); nitrocellulose membranes from Whatman (Dassel, Germany); rabbit anti-LC3 antibody from MBL International (Woburn, MA); goat anti-rabbit antibody from Chemicon (Billerica, MA); and chemiluminescence reagents from GE Sciences (Buckinghamshire, UK).

Hepatocyte isolation and culture.

Primary hepatocytes from wild-type and GFP-LC3 transgenic C57BL/6 male mice were isolated by a two-step collagenase perfusion, as described (20). Hepatocytes were cultured overnight in 5% CO2-95% air at 37°C on Type 1 collagen-coated, 35-mm glass-bottom dishes (300,000 cells per dish) in Waymouth's MB-752/1 growth medium (WM) supplemented with 27 mM NaHCO3, 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 nM insulin, and 100 nM dexamethasone. Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Medical University of South Carolina.

Loading of fluorophores and induction of autophagy.

GFP-LC3 hepatocytes were incubated with 300 nM TMRM, a mitochondria potential-indicating fluorophore, or 500 nM LTR, a probe of acidic organelles, for 30 min at 37°C in WM supplemented with 25 mM Na-HEPES buffer, pH 7.4, 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 nM insulin, and 100 nM dexamethasone. In some experiments, GFP-LC3 hepatocytes were coloaded with LTR and 300 nM MFFR. In other experiments, wild-type hepatocytes were colabeled with 3 μl/ml PicoGreen, a probe for labeling mtDNA (2), and 500 nM LTR. To induce autophagy by nutrient deprivation, hepatocytes were placed in Krebs-Ringer-HEPES buffer (KRH, 115 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM KH2PO4, 1.2 mM MgSO4, and 25 mM Na-HEPES buffer, pH 7.4) plus 1 μM glucagon (KRH/G). In all experiments, one-third of the initial concentration of TMRM or LTR and PicoGreen was kept in subsequent incubation media after washes to maintain equilibrium distribution of the fluorophores.

Laser-scanning confocal microscopy.

Images were collected using a Zeiss LSM 510 NLO laser-scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) with a ×63 numerical aperture 1.4 oil immersion planapochromat objective lens. Temperature of the microscope stage was maintained at 37°C using an environmental chamber. LTR and TMRM were excited at 543 nm by a helium-neon laser attenuated to <2% of full power, and emission was collected through a 560-nm long-pass filter. GFP-LC3 and PicoGreen were excited at 488 nm by an argon laser at <2% of full power, and emission was collected through a 500- to 530-nm band-pass filter. MFFR was excited at 633 nm by a helium-neon laser, and emission was collected through a 650-nm long-pass filter. For time-lapse experiments, images were acquired approximately every 1 min for up to 130 min.

Quantification of autophagic structures and mitochondrial polarization.

Numbers of GFP-labeled LC3 patches (PAS), cup-shaped structures (phagophores), and rings with and without red TMRM fluorescence (polarized mitophagosomes and depolarized autophagosomes, respectively) were counted in blinded fashion in confocal images of single hepatocytes from three independent experiments from three different hepatocyte isolations. Loss of TMRM typically occurred rapidly, and mitochondria were judged depolarized after >50% of fluorescence was lost. Pixel intensity for TMRM fluorescence of individual mitochondria was assessed by selected area analysis in Photoshop CS4 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). Similarly, numbers of red-fluorescing, LTR-labeled structures were also counted.

Western analysis.

Hepatocytes were harvested by scraping in RIPA buffer (20 mM Tris·HCl buffer, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 0.1% NP-40 containing protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails, as recommended by the manufacturer) and sonicated on ice using an ultrasonic cell disruptor (Misonex, Farmingdale, NY). Lysates were centrifuged at 13,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. Protein concentration was measured using a BCA procedure, as recommended by the manufacturer. Cell lysates were resolved on 4 to 15% polyacrylamide gels and electrotransferred onto the nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking with 5% nonfat milk in TBST (10 mM Tris·HCl buffer, pH. 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h, membranes were immunoblotted with anti-LC3 antibody diluted 1:1,000 in TBST. Primary antibody was detected with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody using a chemiluminescence kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. A nonspecific band was used to confirm equal loading of protein.

Statistical analysis.

Results are plotted as means ± SE. Statistical analysis was performed by Student's t-test or ANOVA using SigmaPlot 10 (Systat Software, Chicago, IL) with P < 0.05 as the criterion of significance.

RESULTS

Nutrient deprivation stimulates autophagosome formation in cultured GFP-LC3 hepatocytes.

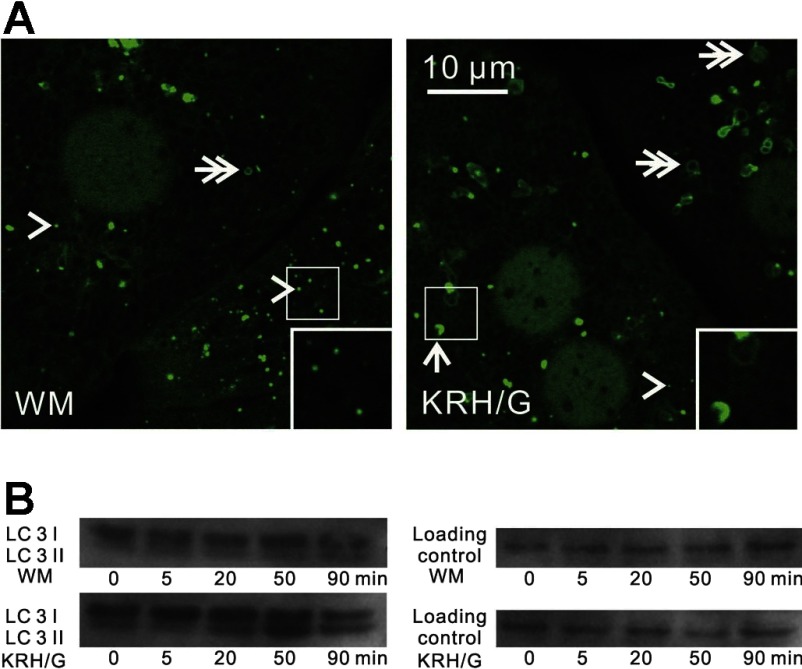

To evaluate the dynamics of autophagy, we examined hepatocytes isolated from GFP-LC3 transgenic mice. When GFP-LC3 hepatocytes were incubated in WM, GFP-LC3 fluorescence was distributed relatively diffusely throughout the cells with a slight concentration in the nucleus. Some GFP-LC3 fluorescence was present in small patches mostly of 0.2 to 0.3 μm in diameter (Fig. 1A, left, arrowheads) and occasional rings ∼1 μm in diameter (Fig. 1A, left, double arrow). After 90 min in nutrient-free KRH plus 1 μM glucagon (KRH/G), the number of GFP-LC3 patches decreased, whereas GFP-labeled cup-shaped structures (Fig. 1, right, arrow), GFP-labeled rings (Fig. 1, right, double arrows), and GFP-labeled solid disks (>0.5 μm) increased. GFP-labeled rings likely represented optical sections through the middle of autophagosomes, whereas GFP-labeled solid disks likely represented oblique optical sections that included edges of autophagosomes extending from one lateral margin to the other. Such disks, rings, and cup-shaped structures are generally referred to as GFP puncta in previous studies. These results are typical of induction of autophagy in cultured GFP-LC3 transgenic hepatocytes by nutrient deprivation.

Fig. 1.

Induction of autophagosomes during nutrient deprivation plus glucagon in GFP-LC3 transgenic mouse hepatocytes. A: hepatocytes from green fluorescent protein (GFP)-microtubule-associated protein-1 light chain 3 (LC3) mice were incubated either in Waymouth's growth medium (WM) or in nutrient-free Krebs-Ringer-HEPES buffer plus glucagon (KRH/G) to stimulate nutrient deprivation. Images were collected after 90 min by laser-scanning confocal microscopy. In WM, the majority of GFP-LC3 fluorescence was diffuse in the cytosol and nucleus or incorporated into green patches [preautophagic structures (PAS), arrowheads] and rarely in disks (autophagosomes, double arrows). In KRH/G, GFP-LC3 fluorescence appeared in numerous rings and disks (autophagosomes, double arrows) and cup-shaped structures (phagophores, arrows). Insets: magnified images of autophagic structures. B: hepatocytes from wild-type mice were incubated in WM or KRH/G for 0 to 90 min, and LC3 I and LC3 II protein expression was assessed in cell extracts by Western blotting, as described in materials and methods.

During autophagy, LC3 I is processed to PE-conjugated LC3 II (14). To confirm stimulation of autophagy in isolated mouse hepatocytes, wild-type hepatocytes from the same breeding colony as the GFP-LC3 transgenic mice were incubated in WM or KRH/G with and without 3MA for 0 to 90 min. LC3 I (18 kDa) and II (16 kDa) protein expression was then determined by Western analysis. In WM, the intensity of LC3 I bands remained unchanged after 5, 20, 50, and 90 min of incubation, and the intensity of LC3 II bands was very faint (Fig. 1B, top gel). By contrast, during incubation in KRH/G, the intensity of LC3 II bands progressively increased for at least 50 min, whereas the intensity of LC3-I bands remained relatively unchanged (Fig. 1B, bottom gel). 3MA, an inhibitor of autophagy, blocked the increase of LC3 II stimulated by KRH/G (data not shown). Taken together, these results showed that incubation of hepatocytes in KRH/G induces robust accumulation of autophagic vacuoles with LC3 processing and redistribution of GFP-LC3 into phagophores and autophagosomes. These findings confirm previous studies showing induction of autophagy in this model (8, 34).

GFP-LC3-labeled phagophores sequester polarized mitochondria during nutrient deprivation.

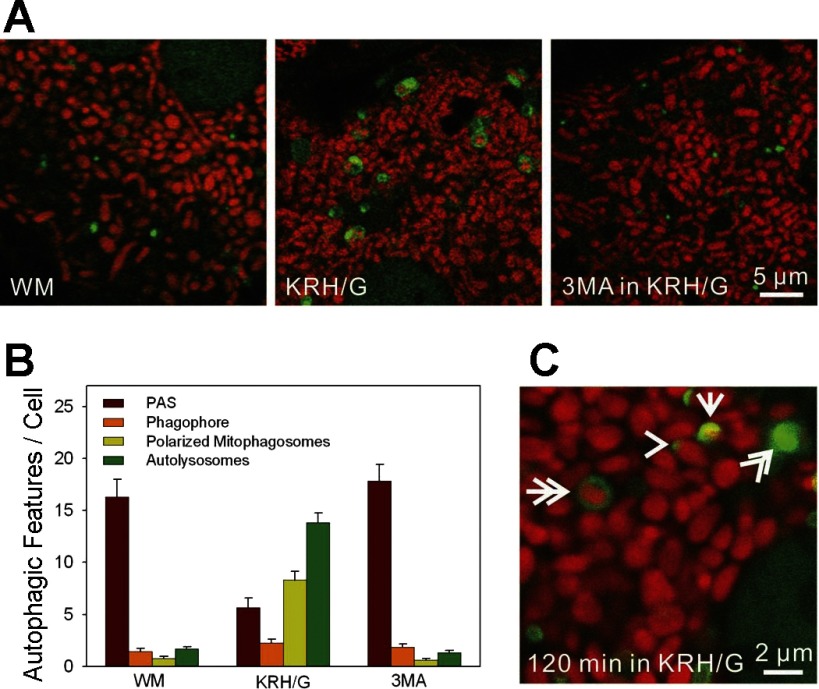

To investigate mitophagy during nutrient deprivation, hepatocytes from GFP-LC3 mice were loaded with TMRM, a red-fluorescing cationic fluorophore that accumulates electrophoretically into mitochondria and labels individual mitochondria with bright red fluorescence (Fig. 2A). Images of the hepatocytes were taken after 90 min in WM, KRH/G, or KRH/G in the presence of 3MA. In WM, a few green rings were present, but GFP-LC3 was predominately observed as small green patches or PAS (Fig. 2A, left). In KRH/G, GFP-LC3 patches decreased in number, as GFP-labeled cup-shaped structures, rings, and disks increased (Fig. 2A, middle). Frequently, TMRM-labeled polarized mitochondria occupied the interior of GFP-labeled rings, disks, and cup-shaped structures (Fig. 2A, middle). 3MA virtually completely suppressed sequestration of polarized mitochondria into GFP-LC3-labeled structures during incubation in KRH/G. In the presence of 3MA, GFP-LC3 remained as diffuse fluorescence and small patches (Fig. 2A, right).

Fig. 2.

Confocal microscopy of mitophagy during nutrient deprivation plus glucagon in GFP-LC3 hepatocytes. GFP-LC3 hepatocytes were loaded with tetramethylrhodamine methylester (TMRM) to label mitochondria, as described in materials and methods. A: confocal images of TMRM-loaded GFP-LC3 hepatocytes incubated in WM (left), KRH/G (middle), or KRH/G plus 10 mM 3-methyladenine (3MA; right) for 90 min. In WM, green-fluorescing GFP-LC3 patches were present that sometimes resided adjacent to red-fluorescing mitochondria. Autophagosomes (green rings and disks) were rare but increased greatly in KRH/G and often enclosed TMRM-labeled mitochondria. 3MA blocked autophagosome formation in WM. B: the numbers of PAS (green patches), phagophores (green cup-shaped structures), polarized mitophagosomes (green rings or disks containing TMRM), and depolarized autophagosomes/autolysosomes (green rings or disks not containing TMRM) per cellular confocal image were quantified for GFP-LC3 hepatocytes incubated as described in A from three different hepatocyte isolations per treatment group. Differences in numbers of PAS, mitophagosomes, and autolysosomes in KRH/G compared with WM and 3MA were statistically significant (P < 0.05, n = 5 cells/group). C: representative structures of a PAS (arrowhead), phagophore (arrow), polarized mitophagosome (double arrow), and autolysosome (double arrowhead).

The distribution of GFP-LC3 into various structures was quantified from images of random fields from three independent experiments (Fig. 2B). Figure 2C illustrates the GFP-LC3-labeled autophagic structures that were scored: patches (PAS, arrowhead), cups (phagophores or isolation membranes, arrow), and rings and disks. On the basis of TMRM labeling, rings and disks were categorized as TMRM positive (polarized mitophagosomes, double arrow) and TMRM negative (depolarized autophagosomes and autolysosomes, double arrowhead). After 90 min in WM, GFP-LC3 was predominantly diffuse or incorporated into PAS patches dispersed throughout the cytosol. In KRH/G, PAS patches decreased 69% compared with WM. In addition, PAS patches were frequently located near polarized mitochondria in KRH/G (Fig. 2C, arrowhead). At the same time, phagophores, polarized mitophagosomes and depolarized autophagosomes/autolysosomes increased 1.55-, 11.1-, and 8.1-fold, respectively. Overall, ∼40% of rings and disks contained TMRM-labeled mitochondria (Fig. 2B), although time-lapse imaging showed that many of the depolarized autophagosomes did initially contain polarized mitochondria (see below). 3MA virtually completely inhibited formation of phagophores, polarized mitophagosomes, and depolarized autophagosomes/autolysosomes after 90 min in KRH/G with retention of a similar number of PAS patches as in WM. Together, these data suggest that GFP-LC3 patches likely serve as nucleation sites that grow into phagophores that engulf polarized mitochondria and hence may appropriately be called PAS.

GFP-LC3-labeled mitophagosomes mature into autolysosomes.

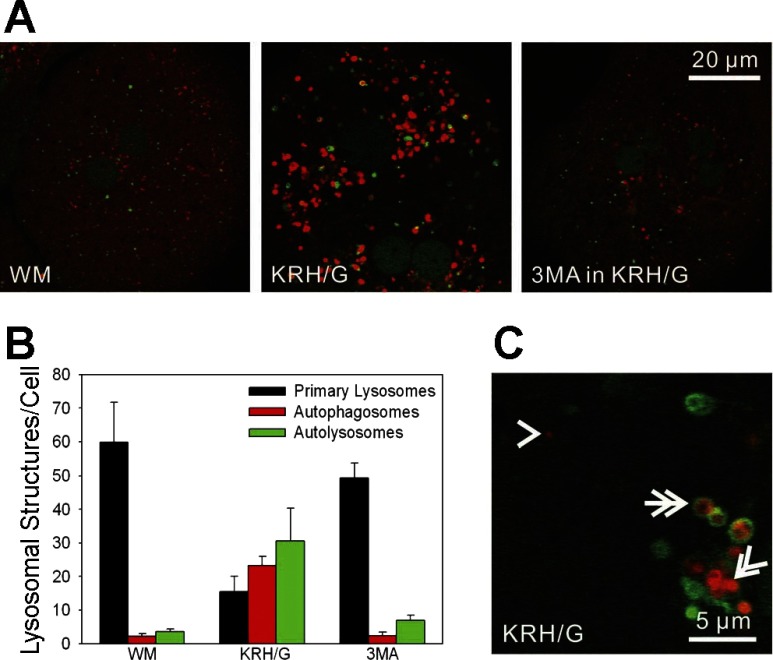

Newly formed autophagosomes fuse with lysosomes to mature into acidic autolysosomes. To characterize intravesicular acidification after autophagic induction by nutrient deprivation, GFP-LC3 hepatocytes were loaded with LTR, a red-fluorescing weak base that accumulates into acidic compartments. In WM, small LTR-labeled red structures of ∼0.2 μm in diameter were present that presumably corresponded to primary lysosomes and late endosomes (Fig. 3A, left). These LTR-labeled vesicles did not colocalize with GFP-LC3. After 90 min incubation in KRH/G, larger LTR-labeled structures increased dramatically in number, whereas small LTR-labeled vesicles decreased (Fig. 3A, middle). Numerous LTR disks were located inside GFP-LC3 rings (Fig. 3C). Although GFP-LC3 cup-shaped structures increased after nutrient deprivation, cup-shaped structures never colocalized with LTR. After 90 min in KRH/G plus 3MA, these nutrient deprivation-induced changes were prevented, and images were virtually indistinguishable from those obtained for hepatocytes incubated in WM (Fig. 3A, right).

Fig. 3.

Acidification of autophagosomes during nutrient deprivation plus glucagon in GFP-LC3 hepatocytes. GFP-LC3 hepatocytes were loaded with LysoTracker Red (LTR) to label acidified vesicles, as described in materials and methods. A: GFP-LC3 hepatocytes were incubated in WM (left), KRH/G (middle), or KRH/G plus 10 mM 3MA (right) for 90 min. After incubation in WM, individual PAS were distributed throughout the cytosol, and LTR staining was mostly confined to small primary lysosomes/late endosomes. In KRH/G, LTR-labeled vesicles proliferated, often in association with GFP-LC3 fluorescence. Cells incubated in KRH/G with 3MA were indistinguishable from cells in WM. B: the numbers of primary lysosomes/acidified late endosomes, acidified autophagosomes, and autolysosomes were quantified from confocal images of GFP-LC3 hepatocytes incubated as described in A from three different hepatocyte isolations per treatment group. Differences in numbers of primary lysosomes, autophagosomes, and autolysosomes in KRH/G compared with WM and 3MA were statistically significant (P < 0.05, n = 5 cells/group). C: representative structures of a primary lysosome (arrowhead), autophagosome (double arrow), and autolysosome (double arrowhead).

The distribution of LTR-labeled structures was quantified from random fields from three independent experiments. LTR-labeled acidic structures were scored as red patches (∼0.2 μm, primary lysosomes/acidified late endosomes) (Fig. 3C, arrowhead), GFP-LC3 rings containing red LTR fluorescence (acidified autophagosomes) (Fig. 3C, double arrow), and solid red disks (autolysosomes) (Fig. 3C, double arrowhead). After 90 min in WM, LTR was predominantly taken up by primary lysosomal patches scattered through the cytosol (Fig. 3B). After 90 min in KRH/G, such primary lysosomes decreased 74% compared with WM. At the same time, autophagosomes and autolysosomes increased 11.2- and 9.9-fold, respectively. 3MA virtually completely prevented these changes from occurring in KRH/G. Overall, these data are consistent with the conclusion that small primary lysosomes/late endosomes participate in autolysosome formation.

After autophagic sequestration, mitochondria depolarize and mitophagosomes acidify.

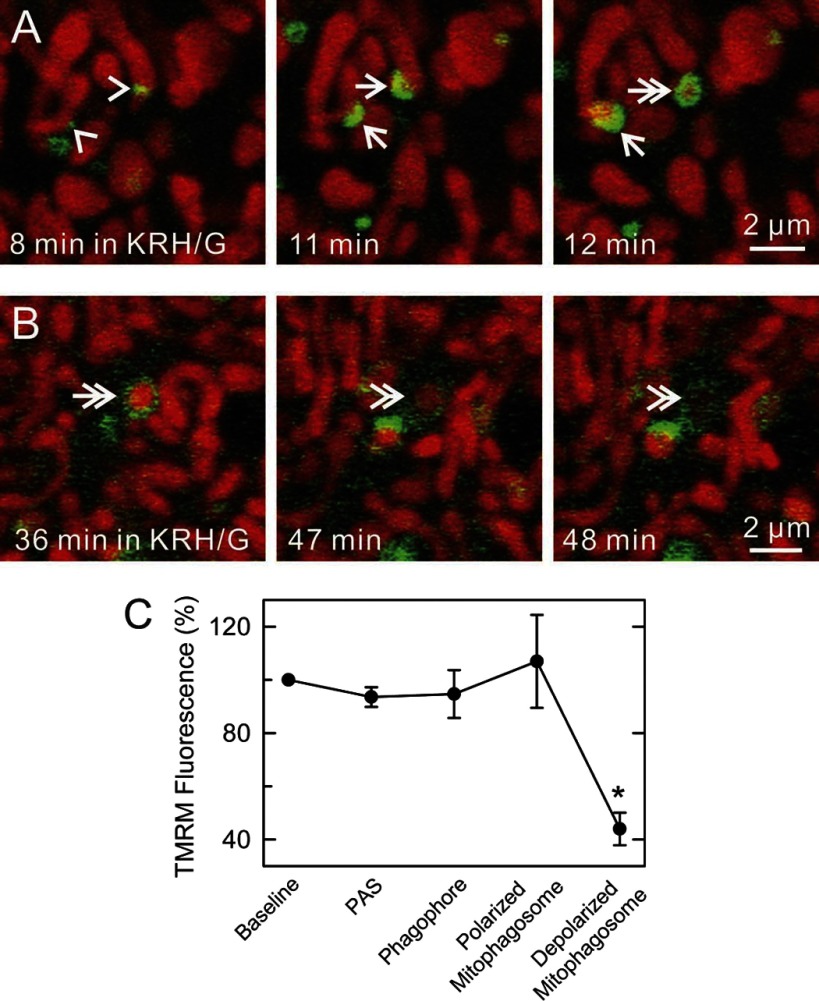

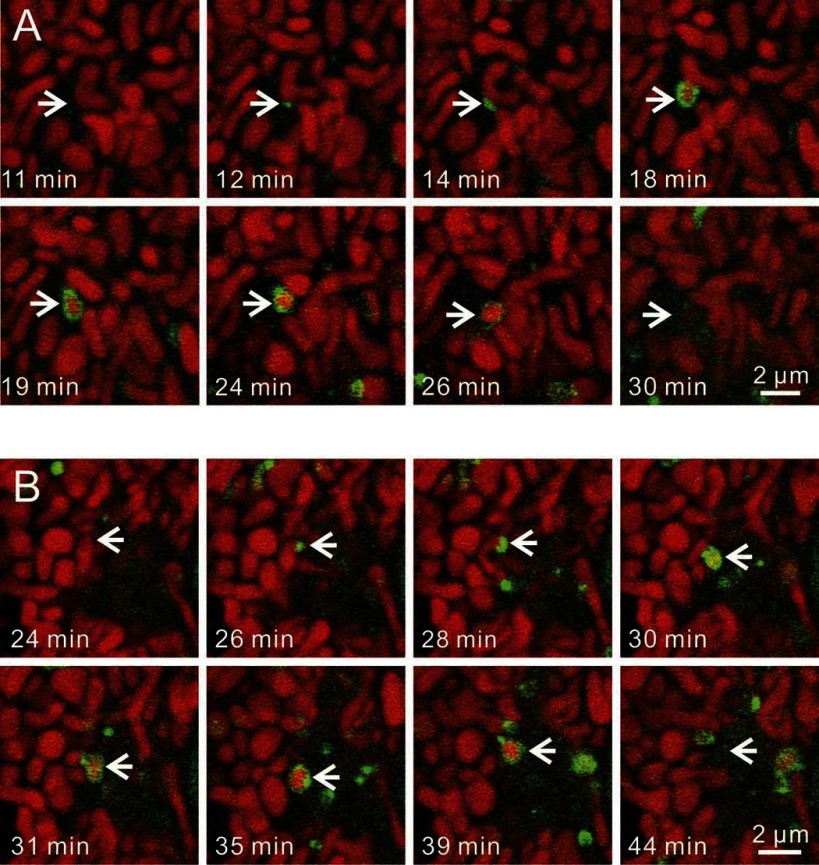

To investigate the dynamics of mitophagosome formation and processing, time-lapse images were collected of GFP-LC3 hepatocytes loaded with TMRM. Mitophagy began with growth of GFP-LC3 patches (PAS, arrowheads) into GFP-LC3 cups (Fig. 4A, arrows). Cup-shaped structures then enveloped and sequestered individual TMRM-labeled mitochondria, resulting in the formation of GFP-labeled rings. The time for transformation of PAS to fully formed phagophores averaged 3.3 ± 0.3 min (n = 28 events), whereas the time for maturation of phagophores to rings was 3.5 ± 0.4 min (n = 28 events). In favorable sections viewing phagophore formation laterally, depolarization of mitochondria (loss of TMRM fluorescence) seemed to occur coordinately with ring closure (Fig. 4A, double arrow). More often, mitophagosome formation was observed obliquely or end-on. Thus, not all rings represented closed vesicles, and TMRM fluorescence was frequently observed inside GFP-LC3 rings (Fig. 4B, double arrows). Whether such TMRM-labeled GFP-LC3 rings represented truly closed vesicles could not be determined. On average, TMRM fluorescence was lost 11.8 ± 1.4 min (n = 11 events) after apparent ring formation (Fig. 4B, double arrowheads). TMRM pixel intensity was measured from images of mitochondria undergoing mitophagy in relation to TMRM intensity to mitochondria not undergoing mitophagy. Changes of TMRM intensity were not observed prior to sequestration or during the maturation of phagophores into autophagosomes (Fig. 4C). Overall, the data indicated that mitochondrial depolarization occurred at or after completion of sequestration (see also Fig. 6). Supplemental Figs. S1–S3 are movies also illustrating these phenomena. (Supplemental Material for this article is available online at the Journal website.)

Fig. 4.

Progression of autophagic sequestration of polarized mitochondria. A and B: TMRM-loaded GFP-LC3 hepatocytes were incubated in KRH/G, and time-lapse images of TMRM-labeled mitochondria were collected every minute. Representative images are shown. In favorable views along the long axis of forming phagophores, note progression from a GFP-LC3 (green)-labeled PAS patch (arrowheads) to a cup-shaped phagophore (arrows) to a ring-shaped mitophagosome (double arrows). Loss of red TMRM fluorescence (mitochondrial depolarization) occurred at or after ring closure (double arrowheads). C: TMRM fluorescence intensity of mitochondria during the progression of mitophagy is plotted. Baseline is background-subtracted TMRM fluorescence of cellular mitochondria not in association with GFP-LC3 normalized to 100%. Other fluorescence values are for same cell mitochondria in association with PAS, phagophores, and GFP-LC3 rings before and after the beginning of mitochondrial depolarization. *P < 0.05 compared with other groups; n ≥ 4 per group.

Fig. 6.

Mitochondrial fission during nutrient deprivation-induced mitophagy. GFP-LC3 hepatocytes were loaded with TMRM and incubated in KRH/G. Images were collected every minute. A: a PAS became associated with the middle part of a TMRM-labeled mitochondrion and elongated to form a phagophore (arrows). The middle part of the mitochondria was then enveloped, and completion of sequestration occurred coordinately with mitochondrial fission. Afterward, the sequestered mitochondrial fragment depolarized, as shown by loss of red TMRM fluorescence. B: a PAS localized to the end of a TMRM-labeled mitochondrion and elongated into a phagophore (arrows). Again, completion of sequestration occurred coordinately with mitochondrial fission and was followed by depolarization of the sequestered mitochondrion.

In some instances, GFP-LC3 developed into phagophores that did not sequester polarized mitochondria (data not shown). Such events were the minority (14.7%) with the remainder of sequestrations involving polarized mitochondria (85.3%). Consistently, the mitophagic process during nutrient deprivation began from single GFP-LC3 patches in association with target mitochondria. Moreover, as autophagy progressed, the number of GFP patches in the cytoplasm decreased (Fig. 2B). These data support the conclusion that GFP-LC3 patches are indeed PAS that act as nucleation and initiation sites for mitophagy.

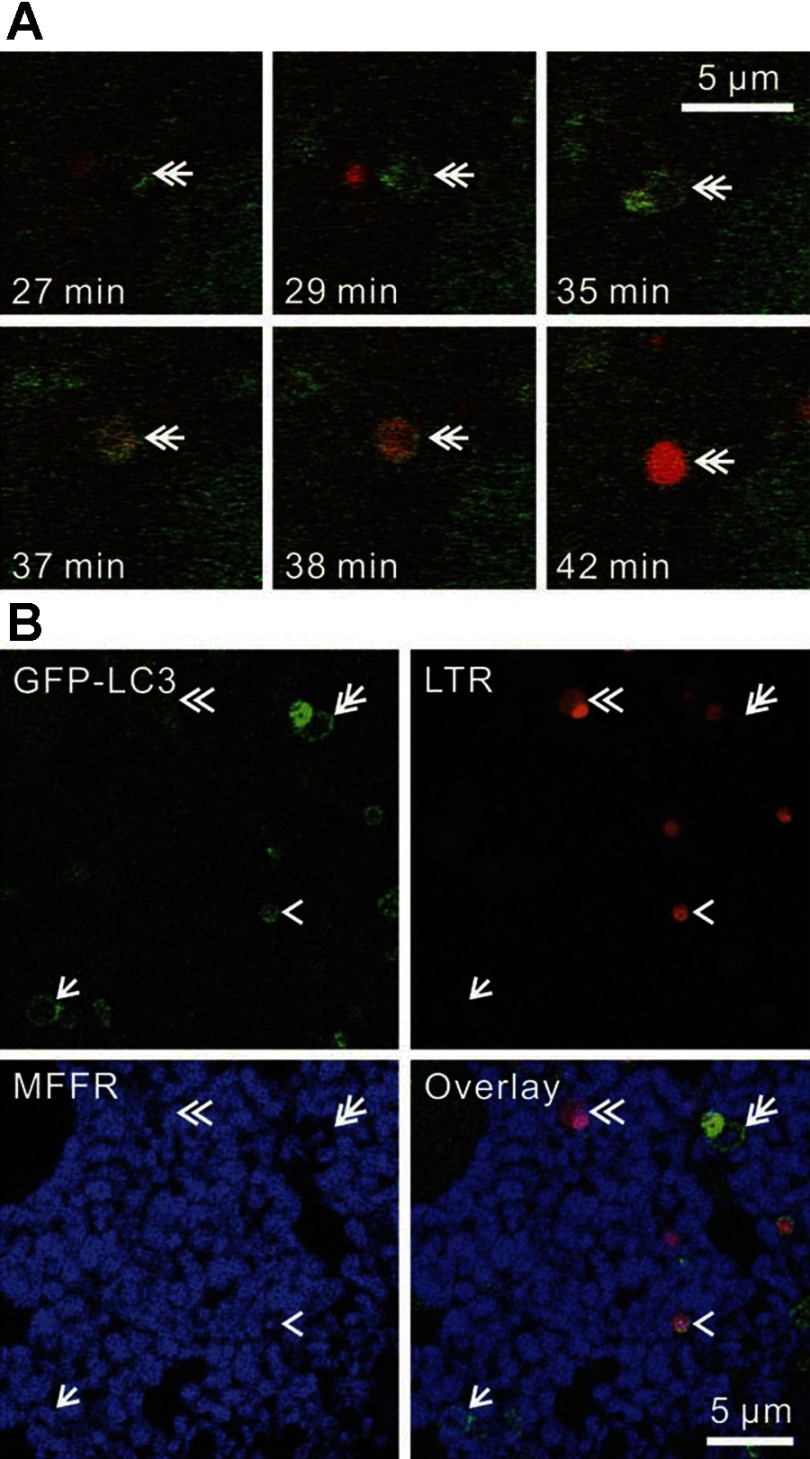

In other experiments, time-lapse images of GFP-LC3 hepatocytes loaded with LTR were collected during incubation in KRH/G. Here in the absence of TMRM, PAS again grew into phagophores and then into rings with a time course similar to that observed for TMRM-labeled hepatocytes (Fig. 5A). LTR did not localize to PAS and phagophores. Rather, LTR uptake occurred only after ring formation. The time after ring formation that LTR began was difficult to assess because uptake began very gradually and imperceptively (Fig. 5A, top right and bottom left). In the example in Fig. 5A, LTR uptake seemed to begin 6 to 8 min after GFP-LC3 ring formation. However, once clearly evident, LTR uptake then proceeded relatively rapidly, leading to maximal LTR uptake in another 2 to 3 min. Overall, fully evident LTR accumulation indicating acidification was observed after an average of 9.9 ± 1.9 min (n = 28) following apparent GFP-LC3 ring formation (Fig. 5A). Subsequent to strong LTR labeling of autophagosomes, GFP-LC3 fluorescence was frequently lost altogether (Fig. 5A, bottom right).

Fig. 5.

Acidification of autophagosomes. A: LTR-loaded GFP-LC3 hepatocytes were incubated in KRH/G, and time-lapse images were collected every minute. Double arrows indicate the formation and maturation of an autophagosome. In this example, autophagosome formation (GFP-LC3 ring) was complete at 29 min and was followed by vesicular acidification (LTR uptake) beginning between 35 and 37 min. Acidification (LTR uptake) become maximal at ∼42 min. B: GFP-LC3 hepatocytes were loaded with LTR and MitoFluor Far Red (MFFR) and incubated 90 min in KRH/G. Arrows, double arrows, arrowheads, and double arrowheads indicate a polarized mitophagosome, a later depolarizing mitophagosome, an autolysosome still containing GFP-LC3 fluorescence, and a later autolysosome that has lost remnants of GFP-LC3, respectively.

To confirm that GFP-LC3-labeled mitophagosomes matured into LTR-loaded autolysosomes, GFP-LC3 hepatocytes were coloaded with MFFR to monitor mitochondrial membrane potential and LTR to monitor acidification and then incubated in KRH/G for 90 min. Similar to our observations with TMRM-labeled mitochondria (Fig. 2A), GFP-LC3 formed phagophores that engulfed MFFR-labeled mitochondria (pseudocolored blue) to form nonacidified polarized mitophagosomes (Fig. 5B, arrow). Other presumably more mature mitophagosomes retained less MFFR fluorescence (Fig. 5B, double arrow). Fusion of primary lysosomes then led to acidified autophagosomes still containing remnants of GFP-LC3 (Fig. 5B, arrowhead), which were then lost (Fig. 5B, double arrowhead). Unlike TMRM, some MFFR was sometimes retained in late mitophagosomes and autolysosomes, suggesting nonspecific binding of MFFR to mitochondrial components or slow redistribution of MFFR after changes of membrane potential. Together, these data indicate that mitophagosomes mature into acidified autolysosomes.

Mitochondrial fission occurs coordinately with mitophagy.

Frequently, phagophores sequestered portions of individual mitochondria rather than whole mitochondria into mitophagosomes (Fig. 6). This mitochondrial fission occurred as LC3-labeled rings formed, as if phagophores were pinching off portions of mitochondria. Fission events during mitophagy occurred from both the middle (Fig. 6A) and ends of individual mitochondria (Fig. 6B). Fission during mitophagy from middles and ends occurred 9.1% and 43.1% of the time, respectively, with sequestration of whole mitochondria occurring in the remainder. The intensity of TMRM fluorescence did not appear to differ between the sequestered and nonsequestered portions of mitochondria being targeted for mitophagy (see Fig. 4C). Mitochondria depolarized only after fission and ring formation were complete. Overall, these findings indicated that mitochondrial fission occurred in close coordination with autophagosome formation. Supplemental Figs. S3–S5 are movies also illustrating mitochondrial fission occurring coordinately with mitophagy.

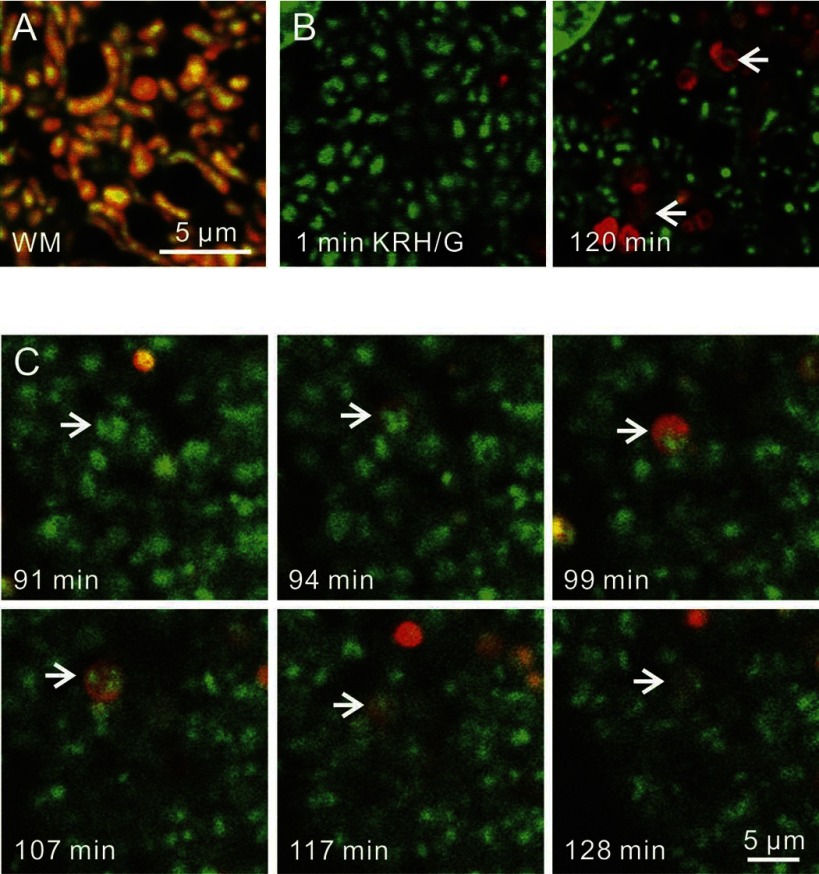

Mitophagy sequesters and degrades mitochondrial DNA.

Mitochondria are a major source of ROS, which can lead to mutations in mtDNA. mtDNA lacks histones, and mitochondria have limited DNA repair capacity compared with the nucleus, which makes mtDNA more vulnerable to oxidative damage (45). To investigate a role of mitophagy in mtDNA degradation and turnover, hepatocytes from wild-type mice were colabeled with green-fluorescing PicoGreen and red-fluorescing TMRM or LTR. PicoGreen is a DNA-intercalating fluorophore that penetrates mitochondrial membranes and labels mtDNA. In hepatocytes incubated in WM, virtually every TMRM-labeled mitochondria contained PicoGreen-labeled mtDNA nucleoids, which were yellow in the overlay (Fig. 7A). Virtually no PicoGreen-labeled structures were present in the cytoplasm that did not colocalize with mitochondria. Hepatocytes were also coloaded with PicoGreen and LTR. After only 1 min in KRH/G, almost no PicoGreen-labeled mtDNA nucleoids colocalized with LTR (Fig. 7B, left, arrows). Similarly, for hepatocytes in WM, very little colocalization of LTR and mtDNA was observed (data not shown). By contrast, after 120 min in KRH/G, PicoGreen-labeled structures were less numerous and now present in some LTR-labeled vesicles (Fig. 7B, arrows). Time-lapse confocal imaging showed envelopment of mtDNA nucleoids by LTR as mitophagosomes formed during incubation in KRH/G (Fig. 7C, arrows; see also Supplemental Fig. S6). Subsequently, after vesicular acidification, the intensity of PicoGreen decreased, indicating degradation of mtDNA. Overall, these results showed that individual polarized mitochondria in hepatocytes contain multiple copies of mtDNA in distinct nucleoids. During mitophagy, mitochondria and this mtDNA are sequestered into mitophagosomes, which acidify and then degrade the mtDNA. Thus, mitophagy is an important mechanism for mtDNA degradation and turnover.

Fig. 7.

Mitochondrial DNA sequestration and degradation by mitophagy. Hepatocytes from wild-type mice were coloaded with green-fluorescing PicoGreen to label DNA and red-fluorescing TMRM or LTR, as described in materials and methods. A: PicoGreen- and TMRM-loaded hepatocytes were incubated in WM. Note one to several mtDNA nucleoids inside individual mitochondria that appear yellow in the overlay. B: PicoGreen and LTR-colabeled hepatocytes were incubated in KRH/G, and images were collected at 1 and 120 min. Initially, PicoGreen-labeled mtDNA rarely localized with LTR. After 120 min incubation with KRH/G, some LTR-labeled autolysosomes contained PicoGreen staining (arrows). In the top left corner is a portion of a nucleus, which also strongly labeled with PicoGreen. C: time-lapse images of PicoGreen and LTR-colabeled hepatocytes in KRH/G were collected. Arrows identify mtDNA nucleoids of a single mitochondrion that was subsequently sequestered by mitophagy. Afterward, PicoGreen fluorescence of the sequestered mtDNA decreased and virtually disappeared.

DISCUSSION

Mitophagy is suggested to be a major degradation mechanism by which mitochondria turn over. In hepatocytes during nutrient deprivation, mitochondria are degraded at a rate of ∼2.5% per hour and ∼20% of mitochondria are degraded after 12 h (8). However, the dynamics of mitophagy of individual hepatic mitochondria have not been well studied. Here, we investigated mitophagy in GFP-LC3-expressing mouse hepatocytes. In GFP-LC3 hepatocytes cultured in complete growth medium, GFP-LC3 fluorescence was diffuse in the cytosol or incorporated into small patches of mostly 0.2 to 0.3 μm in diameter. Some concentration of GFP-LC3 was also observed in the nucleus, and occasional GFP-LC3 rings characteristic of autophagosomes were also present in complete growth medium (Fig. 1). The small patches likely represented PAS, as described in yeast. PAS contain complexes of Atg proteins forming a perivacuolar structure in yeast (16, 38, 39). PAS elongate into cup-shaped phagophores and then close off into autophagosomes.

The origin of phagophores has been controversial. From some studies, ribosome-free regions of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) or Golgi complex are proposed as the source of these membranes (7, 12, 46). However, the lipid and protein composition of autophagosomal membranes differs from membranes of the ER and Golgi complex (16). Other studies suggest that isolation membranes originate from a novel membranous structure that is neither ER nor Golgi (10). A more recent speculation is that the membranous structure of isolation membranes is donated from the organelle to be sequestered into autophagosomes. For example, Atg9, a transmembrane protein, rapidly cycles between PAS and mitochondria in yeast, suggesting that mitochondria may supply lipids and proteins to forming autophagosomes (32). Similarly, mitochondria of vertebrate cells appear to supply membranes for autophagosome biogenesis during nutrient deprivation (13). In the present study, GFP-labeled patches (PAS) decreased by 69% during incubation of hepatocytes in nutrient deprivation medium (KRH-G) compared with complete growth medium (WM). Loss of PAS was accompanied by a corresponding increase in phagophores (green cup-shaped structures) and autophagosomes (GFP-LC3 rings and disks; Fig. 1A).

Omegasomes are phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate (PI3P)-enriched, endoplasmic reticulum-associated structures that localize close to and around forming autophagosomes (3). Omegasome formation in HEK 293 cells requires PI3 kinase (Vps34) activation, whereas activation of PI3 kinase is not required for PAS in yeast but rather for growth of PAS into phagophores/isolation membranes (39). In the present work, under nutrient-rich conditions, we observed GFP-LC3 patches (PAS) that were not acidified and hence were not simply small autophagosomes. During nutrient deprivation, these small structures elongated into phagophores/isolation membranes that eventually engulfed mitochondria to form autophagosomes that quickly acidified. In the presence of 3MA, an inhibitor of PI3 kinase, this phagophore growth from GFP-LC3 patches was prevented, but the frequency of patches was essentially identical to cells in nutrient-rich medium. Thus, the patches do not require PI3 kinase activation, and we propose that they are PAS analogous to PAS in yeast, which contain Atg8, the yeast homologue of LC3. Nonetheless, future experiments will be needed to determine other molecular components of mammalian PAS.

After nutrient deprivation, ∼40% of GFP-LC3 rings and disks contained TMRM-labeled polarized mitochondria (Fig. 2). This was an underestimate of the true percentage of autophagosomes containing mitochondria or mitochondrial remnants, since mitochondria depolarized after autophagic sequestration, and time-lapse confocal imaging showed that 85% of newly forming autophagosomes contained mitochondria. As expected, the autophagy inhibitor 3MA suppressed formation of phagophores and mitophagosomes (Fig. 2, A and B). Moreover, 3MA inhibited proliferation of LTR-labeled autolysosomes that was induced during the nutrient deprivation, (Fig. 3). LC3 II formation also increased during nutrient deprivation plus glucagon (Fig. 1B), which confirmed the induction of autophagy (14).

In time-lapse images, PAS became closely associated with polarized mitochondria prior to formation of phagophores (Figs. 2C, 4, and 6). PAS elongated into cup-shaped phagophores around individual mitochondria in 3.3 ± 0.3 min, which then matured into ring structures in another 3.4 ± 0.4 min (Fig. 3A). However, not all rings represented completely formed autophagosomes. In favorable sections through the long axis of phagophores, cup-shaped phagophores formed that almost completely surrounded individual polarized mitochondria without yet fusing to form a closed vesicle. Such structures viewed from other angles would appear to be a closed ring of GFP-LC3 fluorescence despite remaining open at one end. In such favorable sections, depolarization occurred at or very shortly after completion of sequestration. Additionally, potential-indicating probes like TMRM require time to redistribute across membranes after changes of membrane potential. Redistribution time depends both on the probe and the vesicle surface-to-volume ratio, which is high for the cristae-containing mitochondrial inner membrane and lower for simple autophagosomes (35, 44). Overall, loss of TMRM fluorescence occurred in 11.8 ± 1.4 min after the first appearance of rings, but the time of depolarization after complete closure of the forming autophagosomes is likely less. Nonetheless, mitochondrial depolarization appeared to occur at or after the completion of autophagic sequestration. Thus, mitochondrial depolarization itself was not the signal initiating closure of phagophores and completion of autophagic sequestration. Also, we saw no evidence of partial mitochondrial depolarization prior to autophagic sequestration.

After ring formation, acidification occurred gradually at first and then more rapidly to become fully evident after 9.9 ± 1.9 min as assessed by LTR uptake in time-lapse images (Fig. 5A). In a previous study, the lifetime of LTR-labeled autolysosomes was measured to be ∼9 min by time-lapse confocal imaging (34, 35). This lifetime of autolysosomes is difficult to assess precisely, since degradation of autolysosomes cannot be easily distinguished from movement of autolysosomes out of the confocal plane. However, electron microscopic morphometry also indicates a half-lifetime for autophagosomes of ∼9 min in liver after autophagy is suppressed with insulin (30).

During nutrient deprivation-induced mitophagy, often only a portion of an individual mitochondrion became sequestered into an autophagosome because of concurrent and apparently well-coordinated mitochondrial fission (Fig. 6). Overall, fission occurred in about half of autophagic events with both ends and middle portions of mitochondria becoming sequestered. As judged by the intensity of TMRM fluorescence, mitochondrial membrane potential of the sequestering and nonsequestering parts was not different (Fig. 6C). These findings show that mitochondrial fission often occurs coordinately with mitophagosome formation.

Cell death and signs of cellular stress were negligible after incubation up to 2 h in nutrient-free KRH (data not shown), consistent with our previous studies of hepatocytes showing virtually no nuclear labeling with propidium iodide or Trypan blue, little release of lactate dehydrogenase, no cell shrinkage and detachment, no zeiotic or other blebbing, no TUNEL, and no mitochondrial depolarization (18, 31). Additionally, after nutrient deprivation in vivo (fasting) of GFP-LC3 transgenic mice, autophagy is strongly upregulated, but negligible hepatocellular death occurs (27).

In a recent report appearing after the present work was completed, mitochondrial fission and autophagy were characterized in Ins1 insulinoma cells (43). Mitochondrial fission and partial depolarization preceded mitophagy, as assessed by accumulation of MitoTracker Red-labeled mitochondria into GFP-LC3-labeled structures in the presence of protease inhibitors. Mitochondria undergoing mitophagy contained decreased optic atrophy type 1 (Opa1), a fusion-promoting protein in mitochondria. Moreover, overexpression of Opa1 and suppression of fission-1 (Fis1) or dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1), two proteins involved in mitochondrial fission, decreased mitophagy. Thus, mitochondrial fission promoted mitophagy, whereas fusion was inhibitory. However, in contrast to the present work in hepatocytes in which mitochondrial fission, depolarization, and autophagic sequestration took place in only a few minutes, mitochondrial fission and depolarization occurred hours before autophagy in Ins1 cells. This striking difference in time course may be due to differences of conditions (nutrient deprivation vs. nutrient replete incubation), cell type (hepatocytes vs. Ins1 cells), and methodologies.

How mitochondrial fission and mitophagy are coordinated remains to be determined. One possibility is that Atg proteins become directly involved in mitochondrial fission. For example, Atg5–Atg12/Atg16 protein complexes, which function in forming sequestering membranes, may also assist in dividing mitochondria. Atg9 is suggested to supply lipids for autophagosomal membranes and may act to insert lipids into mitochondria membranes to assist in fission (32, 38). Another possibility is that LC3 and other Atg proteins collaborate with mitochondrial fusion and fission proteins, such as mitofusin 1 (Mfn1) and Drp1. In primary neurons, mitochondrial fission induced by nitric oxide was accompanied by mitophagy (4). This fission process was inhibited by Mfn1 and dominant negative Drp1 expression. Future experiments will be needed to define the molecular events involved in coordinating mitophagy with mitochondrial fission.

On average, mitochondria of hepatocytes contain four to five copies of mtDNA (6). In complete growth medium, PicoGreen labeling confirmed that each polarized mitochondrion of hepatocytes contained multiple copies of mtDNA in distinct nucleoids (Fig. 5A). After autophagic induction, PicoGreen-labeled mtDNA moved into autolysosomes as mitophagy occurred (Fig. 5, B and C). Thus, mtDNA was not excluded from mitochondria undergoing mitophagy. After maximal autolysosomal acidification as indicated by LTR uptake, PicoGreen fluorescence gradually disappeared, consistent with previous reports of mtDNA degradation by DNAse II of lysosomes (9, 11). mtDNA has a 10- to 20-fold higher mutation rate than nuclear DNA due to the proximity of mtDNA to the ROS-generating respiratory chain, the limited DNA repair capacity of mitochondria, and the lack of protective histones in mtDNA (45). Mutations of mtDNA lead to mitochondrial dysfunction due to absent or abnormal synthesis of one or more of the 13 protein subunits of oxidative phosphorylation that are encoded by mtDNA. Defective mtDNA in mice leads to shortened life span and earlier onset of alopecia, osteoporosis, kyphosis, anemia, and reduced fertility, characteristic traits of aging in mice and other species, including humans (42). Our study indicates that mitophagy is a major pathway for mtDNA degradation and supports that proposal that mitophagy plays an important role in elimination of damaged and mutated mtDNA in cells (24).

In summary, nutrient deprivation accelerated mitophagy in cultured rat hepatocytes. Since mitochondria were sequestered in 85% of autophagosomes but comprise only 20% of the volume of the cytosol, nutrient deprivation-induced autophagy would appear to involve, at least in part, selective mitophagy. In this mitophagy, PAS first associated with polarized mitochondria and in a few minutes grew into cup-shaped phagophores that enveloped and sequestered target mitochondria in autophagic vesicles. Frequently, mitophagy occurred coordinately with mitochondria fission. Abrupt mitochondrial depolarization occurred at or following sequestration. Lastly, the fully formed mitophagosomes acidified and their contents, including mtDNA, degraded. These events provide a framework for analyzing mitophagy in disease.

GRANTS

This was supported, in part, by Grants DK073336, DK37034, CA119079, and 1 P01 DK59340 from the National Institutes of Health, with animal facility support from RR015455. Imaging facilities were supported, in part, by Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA138313.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Noboru Mizushima (Tokyo Medical and Dental University) for GFP-LC3 mice.

This work was submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy for I. Kim at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Present address of I. Kim: Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, 3501 Civic Center Blvd., Philadelphia, PA 19104.

REFERENCES

- 1. Arstila AU, Trump BF. Studies on cellular autophagocytosis. The formation of autophagic vacuoles in the liver after glucagon administration. Am J Pathol 53: 687–733, 1968. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ashley N, Harris D, Poulton J. Detection of mitochondrial DNA depletion in living human cells using PicoGreen staining. Exp Cell Res 303: 432–446, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Axe EL, Walker SA, Manifava M, Chandra P, Roderick HL, Habermann A, Griffiths G, Ktistakis NT. Autophagosome formation from membrane compartments enriched in phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate and dynamically connected to the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol 182: 685–701, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barsoum MJ, Yuan H, Gerencser AA, Liot G, Kushnareva Y, Graber S, Kovacs I, Lee WD, Waggoner J, Cui J, White AD, Bossy B, Martinou JC, Youle RJ, Lipton SA, Ellisman MH, Perkins GA, Bossy-Wetzel E. Nitric oxide-induced mitochondrial fission is regulated by dynamin-related GTPases in neurons. EMBO J 25: 3900–3911, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bellu AR, Komori M, van der Klei IJ, Kiel JA, Veenhuis M. Peroxisome biogenesis and selective degradation converge at Pex14p. J Biol Chem 276: 44570–44574, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen XJ, Butow RA. The organization and inheritance of the mitochondrial genome. Nat Rev Genet 6: 815–825, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dunn WAJ. Studies on the mechanisms of autophagy: formation of the autophagic vacuole. J Cell Biol 110: 1923–1933, 1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Elmore SP, Qian T, Grissom SF, Lemasters JJ. The mitochondrial permeability transition initiates autophagy in rat hepatocytes. FASEB J 15: 2286–2287, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Evans CJ, Aguilera RJ. DNase II: genes, enzymes and function. Gene 322: 1–15, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fengsrud M, Roos N, Berg T, Liou W, Slot JW, Seglen PO. Ultrastructural and immunocytochemical characterization of autophagic vacuoles in isolated hepatocytes: effects of vinblastine and asparagine on vacuole distributions. Exp Cell Res 221: 504–519, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fisher J, Bartoov B. DNase II in bull and ram sperm tail and mitochondria. Arch Androl 4: 157–170, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Furuno K, Ishikawa T, Akasaki K, Lee S, Nishimura Y, Tsuji H, Himeno M, Kato K. Immunocytochemical study of the surrounding envelope of autophagic vacuoles in cultured rat hepatocytes. Exp Cell Res 189: 261–268, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hailey DW, Rambold AS, Satpute-Krishnan P, Mitra K, Sougrat R, Kim PK, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Mitochondria supply membranes for autophagosome biogenesis during starvation. Cell 141: 656–667, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Ueno T, Yamamoto A, Kirisako T, Noda T, Kominami E, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J 19: 5720–5728, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kanki T, Wang K, Cao Y, Baba M, Klionsky DJ. Atg32 is a mitochondrial protein that confers selectivity during mitophagy. Dev Cell 17: 98–109, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kim J, Huang WP, Stromhaug PE, Klionsky DJ. Convergence of multiple autophagy and cytoplasm to vacuole targeting components to a perivacuolar membrane compartment prior to de novo vesicle formation. J Biol Chem 277: 763–773, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim J, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy, cytoplasm-to-vacuole targeting pathway, and pexophagy in yeast and mammalian cells. Annu Rev Biochem 69: 303–342, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kim JS, Qian T, Lemasters JJ. Mitochondrial permeability transition in the switch from necrotic to apoptotic cell death in ischemic rat hepatocytes. Gastroenterology 124: 494–503, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kissova I, Deffieu M, Manon S, Camougrand N. Uth1p is involved in the autophagic degradation of mitochondria. J Biol Chem 279: 39068–39074, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kon K, Kim JS, Jaeschke H, Lemasters JJ. Mitochondrial permeability transition in acetaminophen-induced necrosis and apoptosis of cultured mouse hepatocytes. Hepatology 40: 1170–1179, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kotoulas OB, Kalamidas SA, Kondomerkos DJ. Glycogen autophagy in glucose homeostasis. Pathol Res Pract 202: 631–638, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kristensen AR, Schandorff S, Hoyer-Hansen M, Nielsen MO, Jaattela M, Dengjel J, Andersen JS. Ordered organelle degradation during starvation-induced autophagy. Mol Cell Proteomics 7: 2419–2428, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kuma A, Hatano M, Matsui M, Yamamoto A, Nakaya H, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y, Tokuhisa T, Mizushima N. The role of autophagy during the early neonatal starvation period. Nature 432: 1032–1036, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lemasters JJ. Selective mitochondrial autophagy, or mitophagy, as a targeted defense against oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and aging. Rejuvenation Res 8: 3–5, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Menzies RA, Gold PH. The turnover of mitochondria in a variety of tissues of young adult and aged rats. J Biol Chem 246: 2425–2429, 1971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature 451: 1069–1075, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mizushima N, Yamamoto A, Matsui M, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y. In vivo analysis of autophagy in response to nutrient starvation using transgenic mice expressing a fluorescent autophagosome marker. Mol Biol Cell 15: 1101–1111, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Narendra D, Tanaka A, Suen DF, Youle RJ. Parkin is recruited selectively to impaired mitochondria and promotes their autophagy. J Cell Biol 183: 795–803, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Okamoto K, Kondo-Okamoto N, Ohsumi Y. Mitochondria-anchored receptor Atg32 mediates degradation of mitochondria via selective autophagy. Dev Cell 17: 87–97, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pfeifer U. Inhibition by insulin of the formation of autophagic vacuoles in rat liver. A morphometric approach to the kinetics of intracellular degradation by autophagy. J Cell Biol 78: 152–167, 1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Qian T, Herman B, Lemasters JJ. The mitochondrial permeability transition mediates both necrotic and apoptotic death of hepatocytes exposed to Br-A23187. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 154: 117–125, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Reggiori F, Shintani T, Nair U, Klionsky DJ. Atg9 cycles between mitochondria and the pre-autophagosomal structure in yeasts. Autophagy 1: 101–109, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rodriguez-Enriquez S, Kai Y, Maldonado E, Currin RT, Lemasters JJ. Roles of mitophagy and the mitochondrial permeability transition in remodeling of cultured rat hepatocytes. Autophagy 5: 1099–1106, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rodriguez-Enriquez S, Kim I, Currin RT, Lemasters JJ. Tracker dyes to probe mitochondrial autophagy (mitophagy) in rat hepatocytes. Autophagy 2: 39–46, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Scaduto RC, Jr, Grotyohann LW. Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential using fluorescent rhodamine derivatives. Biophys J 76: 469–477, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Seglen PO, Bohley P. Autophagy and other vacuolar protein degradation mechanisms. Experientia 48: 158–172, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Seglen PO, Gordon PB, Holen I. Non-selective autophagy. Semin Cell Biol 1: 441–448, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Suzuki K, Kirisako T, Kamada Y, Mizushima N, Noda T, Ohsumi Y. The pre-autophagosomal structure organized by concerted functions of APG genes is essential for autophagosome formation. EMBO J 20: 5971–5981, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Suzuki K, Ohsumi Y. Current knowledge of the pre-autophagosomal structure (PAS). FEBS Lett 584: 1280–1286, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tal R, Winter G, Ecker N, Klionsky DJ, Abeliovich H. Aup1p, a yeast mitochondrial protein phosphatase homolog, is required for efficient stationary phase mitophagy and cell survival. J Biol Chem 282: 5617–5624, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tracy K, Dibling BC, Spike BT, Knabb JR, Schumacker P, Macleod KF. BNIP3 is an RB/E2F target gene required for hypoxia-induced autophagy. Mol Cell Biol 27: 6229–6242, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Trifunovic A, Wredenberg A, Falkenberg M, Spelbrink JN, Rovio AT, Bruder CE, Bohlooly Y, Gidlof S, Oldfors A, Wibom R, Tornell J, Jacobs HT, Larsson NG. Premature ageing in mice expressing defective mitochondrial DNA polymerase. Nature 429: 417–423, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Twig G, Elorza A, Molina AJ, Mohamed H, Wikstrom JD, Walzer G, Stiles L, Haigh SE, Katz S, Las G, Alroy J, Wu M, Py BF, Yuan J, Deeney JT, Corkey BE, Shirihai OS. Fission and selective fusion govern mitochondrial segregation and elimination by autophagy. EMBO J 27: 433–446, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ward MW, Huber HJ, Weisova P, Dussmann H, Nicholls DG, Prehn JH. Mitochondrial and plasma membrane potential of cultured cerebellar neurons during glutamate-induced necrosis, apoptosis, and tolerance. J Neurosci 27: 8238–8249, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Yakes FM, Van Houten B. Mitochondrial DNA damage is more extensive and persists longer than nuclear DNA damage in human cells following oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 514–519, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yamamoto A, Masaki R, Tashiro Y. Characterization of the isolation membranes and the limiting membranes of autophagosomes in rat hepatocytes by lectin cytochemistry. J Histochem Cytochem 38: 573–580, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. An overview of the molecular mechanism of autophagy. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 335: 1–32, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yin XM, Ding WX, Gao W. Autophagy in the liver. Hepatology 47: 1773–1785, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yokota J, Shires GT. Role of leukocytes in reperfusion injury of skeletal muscle after partial ischemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 257: H1068–H1075, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yu QC, Marzella L. Response of autophagic protein degradation to physiologic and pathologic stimuli in rat hepatocyte monolayer cultures. Lab Invest 58: 643–652, 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhang J, Ney PA. Role of BNIP3 and NIX in cell death, autophagy, and mitophagy. Cell Death Differ 16: 939–946, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.