Abstract

The sodium-taurocholate (TC) cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP) facilitates bile formation by mediating sinusoidal Na+-TC cotransport. During sepsis-induced cholestasis, there is a decrease in NTCP-dependent uptake of bile acids and an increase in nitric oxide (NO) levels in hepatocytes. In rat hepatocytes NO inhibits Na+-dependent uptake of taurocholate. The aim of this study was to extend these findings to human NTCP and to further investigate the mechanism by which NO inhibits TC uptake. Using a human hepatoma cell line stably expressing NTCP (HuH-NTCP), we performed experiments with the NO donors sodium nitroprusside and S-nitrosocysteine and demonstrated that NO inhibits TC uptake in these cells. Kinetic analyses revealed that NO significantly decreased the Vmax but not the Km of TC uptake by NTCP, indicating noncompetitive inhibition. NO decreased the amount of NTCP in the plasma membrane, providing a molecular mechanism for the noncompetitive inhibition of TC uptake. One way that NO can modify protein function is through a posttranslational modification known as S-nitrosylation: the binding of NO to cysteine thiols. Using a biotin switch technique we observed that NTCP is S-nitrosylated under conditions in which NO inhibits TC uptake. Moreover, dithiothreitol reversed NO-mediated inhibition of TC uptake and S-nitrosylation of NTCP, indicating that NO inhibits TC uptake via modification of cysteine thiols. In addition, NO treatment led to a decrease in Ntcp phosphorylation. Taken together these results indicate that the inhibition of TC uptake by NO involves S-nitrosylation of NTCP.

Keywords: sodium-taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide

transport of solutes from the sinusoidal space to the canaliculus provides the driving force for bile formation (1). Bile formation, in turn, depends on the proper functioning of a number of hepatobiliary transporters present on the hepatic sinusoidal (basolateral) and canalicular (apical) membranes. NTCP, present at the basolateral membrane of hepatocytes, mediates the transport of conjugated bile salts such as taurocholate (TC) and taurochenodeoxycholate in a Na+-dependent fashion using the sodium gradient produced by the Na+,K+-ATPase (1, 13, 19, 39). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced cholestasis is associated with a decrease in TC uptake and an increase in proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) (6, 11, 19). At the same time, LPS also initiates a burst of NO production by inducible nitric oxide synthase in all major cell types of the liver (11).

The roles for NO in the liver are diverse and varied. NO plays important roles in regulating hepatic blood flow including portal hypertension (11). NO has both proapoptotic and antiapoptotic actions in the liver (31). Additionally, NO plays important roles in alcoholic liver disease and ischemia/reperfusion injury (31). NO has also been implicated in regulating bile formation. Whereas lower levels of NO have been linked to increased bile flow, higher levels of NO are associated with cholestasis and hepatocellular injury (5, 8, 27, 38, 40). This concentration-dependent effect may result from different proteins that are modified by NO.

It has become increasingly evident that NO exerts many effects in cells by binding to reactive thiols on cysteine residues in a posttranslational modification known as S-nitrosylation (10). S-nitrosylation possesses all of the characteristics of an important posttranslational modification that governs signaling. Namely, it is specific, stimulus evoked, precisely targeted, reversible, and necessary for specific cellular responses (20). The role of S-nitrosylation in liver physiology and pathophysiology has been investigated. As in other tissues, caspases have been shown to be regulated by S-nitrosylation in the liver (22). The enzyme methionine adenosyltransferase, a key regulator of methionine metabolism, is another enzyme that is inhibited by S-nitrosylation (7, 32). Flavin-containing monooxygenase activity can be inhibited by nitric oxide-mediated S-nitrosylation (33). It has also been shown that overall S-nitrosylation levels increase in NO donor-treated hepatic stellate cells (29). Recent work has shown that inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis during induced cholestasis can ameliorate hepatocellular injury by facilitating S-nitrosothiol homeostasis (23). Despite these findings, very little work has been done investigating a role for S-nitrosylation in the regulation of hepatic transporters.

Several lines of evidence raise the possibility that NTCP function may be regulated by S-nitrosylation of one or more of its cysteine residues. Rat Ntcp has eight cysteines, of which four are conserved in human, mouse, and rabbit (45). It has been reported that thiol-binding reagents can block TC uptake in isolated rat hepatocytes (3–4). Moreover, a recent report demonstrated that NO can inhibit TC uptake in isolated rat hepatocytes (37). It is, however, not known whether this inhibition of TC uptake is due to S-nitrosylation of NTCP. Thus the aim of the present study was to test the hypothesis that NO-mediated S-nitrosylation of NTCP results in decreased TC uptake. Our studies suggest that the inhibition of TC uptake by NO involves S-nitrosylation of NTCP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Taurocholate (sodium salt), cysteine, (+)-sodium l-ascorbate, dithiothreitol (DTT), S-methyl methanethiosulfonate (MMTS), and streptavidin agarose were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Sodium nitrite was purchased from JT Baker Chemical (Phillipsburg, NJ). Biotin-HPDP and sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin were purchased from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Sodium nitroprusside (SNP) was purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). An antibody for human NTCP was a gift from Dr. B. Shneider and Dr. F. Chen (Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh) (36). An antibody for rat Ntcp was a gift from Dr. Bruno Stieger (Zurich, Switzerland). An antibody for green fluorescent protein (GFP) was purchased from Clontech (Mountain View, CA). A plasmid encoding Ntcp-GFP was a gift from Dr. J. Dranoff (New Haven, CT). [3H]Taurocholate was purchased from Perkin Elmer (Shelton, CT). [32P]orthophosphate was purchased from MP Biomedicals (Solon, OH). S-nitrosocysteine (SNOC) was prepared fresh by combining equal volumes of 600 mM NaNO2 in H2O with 600 mM l-cysteine in 0.5 M HCl to yield a 300 mM stock solution of SNOC.

HuH-NTCP cell culture.

HuH-NTCP cells were a generous gift from Dr. G. Gores (Mayo Clinic). HuH-NTCP cells were cultured in Dulbecco's minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100,000 units/l penicillin, 100 mg/l streptomycin, and 1.2 g/l of G418 at 37°C under 5% CO2. On experiment days, cells were incubated for 3 h in serum-free media then incubated in a HEPES assay buffer, pH 7.4 (20 mM HEPES, 140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgSO4, 1 mM CaCl2, 0.8 mM KH2PO4, and 5 mM glucose) before determination of TC uptake and NTCP S-nitrosylation. Details of each experiment are provided in the figure legends.

NTCP S-nitrosylation assay.

The biotin switch assay was performed as described previously with minor modifications (9). Cell lysates treated with SNOC or prepared from NO-donor treated HuH-NTCP cells were incubated with a final concentration of 2.5% SDS and 0.2% MMTS for 20 min at 50°C with frequent vortexing to block free thiols. MMTS was removed by acetone precipitation and then the samples were resuspended in HENS buffer (100 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM neocuproine, 1% SDS, pH 8.0) with biotin HPDP and ascorbic acid (0.25 mg/ml and 20 mM final concentrations respectively). Samples were rotated in the dark for 1 h at room temperature. After another acetone precipitation samples were resuspended in 0.25 ml HENS/10 (HENS buffer diluted 1:10 in H2O) buffer followed by the addition of 0.75 ml of neutralization buffer (25 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, pH 7.5). Streptavidin agarose beads (50 μl) were added and samples were rocked overnight at 4°C. Samples were washed four times with wash buffer (neutralization buffer plus 600 mM NaCl) and then eluted with 30 μl elution buffer (HEN/10 buffer containing 1% β-mercaptoethanol). After addition of an equal volume of 2× SDS sample buffer plus β-mercaptoethanol the samples were processed for immunoblot.

Immunoblot.

Following SDS-PAGE, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose. Membranes were blocked with 5% milk in 0.1% Tween-Tris-buffered saline (TTBS) for 1 h at room temperature during rocking. A polyclonal antibody for NTCP was then added to 5% milk-TTBS and incubated with the membrane for 2 h at room temperature during rocking. After three washes with TTBS, membranes were incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-anti-rabbit secondary antibody in 5% milk-TTBS for 1 h at room temperature. Following five washes in TTBS, enhanced chemi luminescence was performed.

TC uptake.

TC uptake in HuH-NTCP cells was determined as previously described (42). Cells were treated with or without NO donors for the indicated times and then incubated with TC containing [3H]TC for 2 min. The cells were then washed thrice with ice-cold HEPES assay buffer and lysed in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 2.5 mM sodium-pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, plus protease inhibitors, pH 7.5). Aliquots of cell lysate were counted for radioactivity and used for protein determination. TC uptake was expressed in nanomoles per minute per protein. To determine the type of inhibition of TC uptake by NO, TC uptake was measured at three different concentrations of SNOC (0, 0.5, and 1 mM) and over a range of TC concentrations (0, 5, 10, 20, 50, and 100 μM). The resulting data were used to estimate the kinetic parameters (Km and Vmax) by fitting the data to Michaelis-Menten equation by using the data analysis software Sigmaplot (Systat Software, Point Richmond, CA). In addition, the data was subjected to Lineweaver-Burk plot to confirm the type of inhibition.

Translocation of NTCP.

A cell surface biotinylation method was used to assess NTCP translocation in HuH-NTCP cells (42). After treatment with or without SNOC for the indicated times, cell surface proteins were biotinylated by exposing hepatoma cells to sulfo-NHS-LC-biotin (0.5 mg/ml) in PBS, pH 8.0 for 45 min on ice. Cells were then washed with PBS + 100 mM glycine, pH 8.0, and cell lysates were prepared. Biotinylated proteins from 50 μg of total lysate were isolated by incubation with streptavidin beads. Biotinylated and total NTCP were determined by immunoblot analysis. The absence of biotinylated GAPDH was routinely monitored to ensure that intracellular proteins were not biotinylated.

Phosphorylation studies.

Determination of the Ntcp phosphorylation was performed as described previously (26) with the following modifications. HuH-NTCP cells were transiently transfected with a Ntcp-GFP construct. At 48 h posttransfection, cells were switched to serum-free media for 3 h and then switched to HEPES assay buffer plus 5 mM glucose containing 0.2 mCi/ml of [32P]orthophosphate for 90 min. During this time the cells were treated for the final 30 min with or without 1 mM SNOC. Cells were washed thrice with ice-cold PBS and the lysates were prepared in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris·HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% deoxycholic acid, 0.1% SDS, pH 7.4). Then 500 μg of lysate was precleared with protein A beads for 4 h during rocking at 4°C. Following the preclear step, the beads were spun down and the precleared lysate was subjected to immunoprecipitation with an antibody for Ntcp for 2 h during rocking at 4°C. Protein A beads were then added and an additional 45-min incubation at 4°C was performed. The purified immune complexes were then washed thrice with RIPA buffer. Beads were then resuspended in a 1:1 mixture of RIPA buffer-2× sample buffer, and samples were boiled and loaded for SDS-PAGE. Following electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and then phosphorylation was determined by performing autoradiography on the membrane. After autoradiography was performed a GFP immunoblot was performed on the same membrane to control for the total amount of Ntcp-GFP that was immunoprecipitated.

Data analysis.

Values are presented as means ± SE, unless otherwise indicated. Differences between groups were analyzed by Student's t-test with P < 0.05 considered significant.

RESULTS

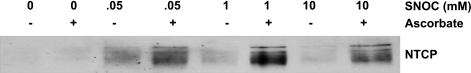

S-nitrosylation of NTCP in SNOC-treated HuH-NTCP lysates.

As an initial test to determine whether NTCP may be modified by NO, we treated lysates from HuH-NTCP cells with the NO donor SNOC and determined whether NTCP is susceptible to S-nitrosylation by NO. We employed a biotin switch assay to determine whether NTCP can be S-nitrosylated. This method has been widely used to determine the S-nitrosylation status of proteins (16). Our results show that over a range of doses (0.05–10 mM) SNOC increases the S-nitrosylation of NTCP compared with the negative control samples treated without ascorbic acid (Fig. 1). NTCP is highly glycosylated and immunoblots with this antibody recognize multiple glycosylated forms of NTCP (36). NTCP immunoblots appear as a very fat band or three to four bands in close proximity depending on the amount of lysate loaded on gels and the length of time that the chemiluminescence reaction is allowed to occur. Note that very little if any NTCP S-nitrosylation was observed in the untreated samples, indicating minimal NTCP S-nitrosylation under basal conditions. These results provide the first evidence, to our knowledge, that a hepatic transporter can be S-nitrosylated and raise the possibility that NTCP may be regulated via S-nitrosylation.

Fig. 1.

S-nitrosocysteine (SNOC)-induced S-nitrosylation of sodium-taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP) in HuH-NTCP lysates. Whole cell lysates were prepared and then left untreated or treated with increasing concentrations the nitric oxide donor SNOC (50 μM, 1 mM, and 10 mM). Excess donor was removed by acetone precipitation, and the biotin switch assay was performed. Samples treated without ascorbic acid served as a negative control. Biotinylated proteins were purified with streptavidin beads and resolved by SDS-PAGE. S-nitrosylated NTCP was identified by probing for NTCP in an immunoblot. S-nitrosylated NTCP is only found in lysates treated with SNOC. This blot is representative of 3 independent experiments (n = 3).

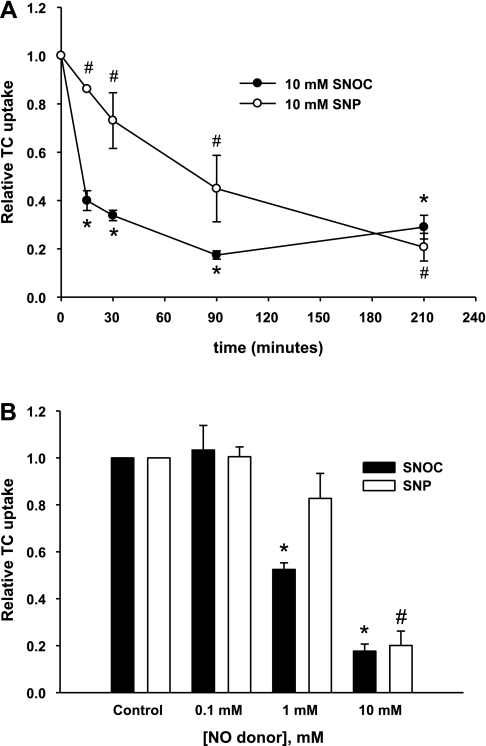

Characteristics of TC uptake inhibition in HuH-NTCP cells by NO.

Previous studies showed that NO inhibits TC uptake in rat hepatocytes (37). However, it is not known whether TC uptake by human NTCP is also affected similarly by NO, and recent studies suggest differences in the type of inhibition between human NTCP and rat Ntcp (21, 35). Moreover, we needed to establish inhibition characteristics of TC uptake by NO in HuH-NTCP cells to relate the effect on NTCP S-nitrosylation. Thus we first characterized the effect of NO on TC uptake in HuH-NTCP cells using two NO donors: SNP and SNOC. Time-dependent studies with 10 mM SNP and SNOC showed that both NO donors inhibited TC uptake as early as 15 min with SNOC inhibiting TC uptake to a greater degree than SNP. Maximal inhibition by SNOC occurs by 90 min whereas maximal inhibition does not occur until 210 min for SNP (Fig. 2A). Control experiments measuring Trypan blue exclusion and lactate dehydrogenase release indicated that these doses and treatment times were not toxic (data not shown). Concentration-dependent studies showed that SNOC was a more potent inhibitor of TC uptake. While TC uptake was inhibited by 1 and 10 mM SNOC, it was only inhibited by 10 mM SNP (Fig. 2B). Taken together, these data indicate that NO inhibits TC uptake by human NTCP. Next we determined the type of inhibition of TC uptake.

Fig. 2.

NO donors SNOC and sodium nitroprusside (SNP) inhibit taurocholate (TC) uptake in HuH-NTCP cells. A: HuH-NTCP cells were incubated with either 10 mM SNOC or 10 mM SNP for different times (0, 15, 30, 90, and 210 min) before determining TC (20 μM) uptake. The values are expressed relative to samples treated with 0 μM of NO donor ± SE. Experiments were performed 3 times (n = 3) and each experiment was performed in triplicate. *P < 0.05 when compared with control samples treated with 0 mM SNOC and #P < 0.05 when compared with control samples treated with 0 mM SNP. B: HuH-NTCP cells were incubated with increasing concentrations (0, 0.1, 1, and 10 mM) of either SNOC or SNP for 3 h in serum-free media followed by an additional 30 min incubation with or without the donors in HEPES assay buffer. These treatments were followed by determination of TC (20 μM) uptake. The values are expressed relative to samples treated with 0 μM of either NO donor ± SE. Experiments were performed 3 times (n = 3) and each experiment was performed in triplicate. *P < 0.05 when compared with control samples treated with 0 mM SNOC and #P < 0.05 when compared with control samples treated with 0 mM SNP.

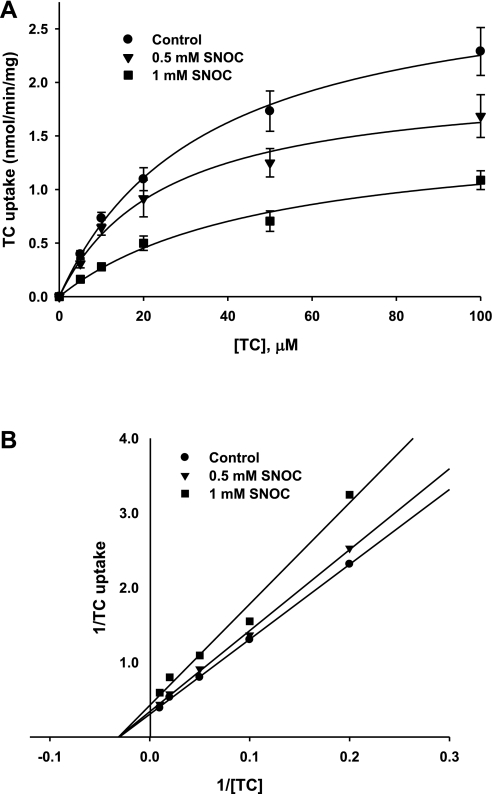

NO inhibits TC uptake noncompetitively in HuH-NTCP cells.

We determined the effect of NO on TC uptake kinetic parameters, Km and Vmax, to further characterize the mechanism by which NO inhibits TC uptake. For these studies, we used the more potent NO donor SNOC at 0.5 mM and 1 mM concentrations. We then measured the initial rate of TC uptake at various concentrations of TC (0–100 μM). The resulting data was fitted to Michaelis-Menten equation (Fig. 3A) to estimate the values of Km and Vmax in the presence and absence of the NO donor, SNOC. Kinetic parameters derived from the fitted data demonstrated that the maximal rate of uptake (Vmax), but not Km, was significantly decreased by SNOC treatment (Table 1). The Lineweaver-Burk plot showed that the regression lines intersected on the x-axis (Fig. 3B). These results indicate noncompetitive inhibition of NTCP-mediated TC uptake by NO as previously reported in isolated rat hepatocytes (27). Since a decrease in Vmax may result from a decrease in plasma membrane NTCP (retrieval of NTCP) among other possibilities (a decrease in functional transporter in the membrane), we determined whether NO affects plasma membrane localization of NTCP.

Fig. 3.

SNOC inhibits TC uptake noncompetitively. A: TC uptake is shown as a function of varying concentrations of TC. HuH-NTCP cells were treated with or without SNOC (control, 0.5 mM, or 1 mM). Following this treatment the initial rate of TC uptake was determined over a range of TC concentrations (0–100 μM). The data shown are means ± SE for control (n = 8), 0.5 mM SNOC (n = 3), and 1 mM SNOC (n = 5). The data were fitted to Michelis-Menten equation with the solid lines representing the best fit. B: Lineweaver-Burk plot of data shown in A. Solid lines represent regression lines through the data points.

Table 1.

Effect of NO on TC uptake kinetic parameters

| SNOC, mM | Vmax, nmol•min−1•mg protein−1 | Km, μM |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3.43 ± 0.17 | 36.5 ± 4.15 |

| 0.5 | 2.04 ± 0.13* | 25.2 ± 4.38 |

| 1 | 1.56 ± 0.18* | 49.0 ± 12.1 |

Km and Vmax were calculated from data shown Fig. 3. The Km for taurocholate (TC) did not significantly change between control cells and either 0.5 mM or 1 mM S-nitrosocysteine (SNOC)-treated cells. However, the Vmax was significantly decreased by both 0.5 mM and 1 mM SNOC (*P < 0.05).

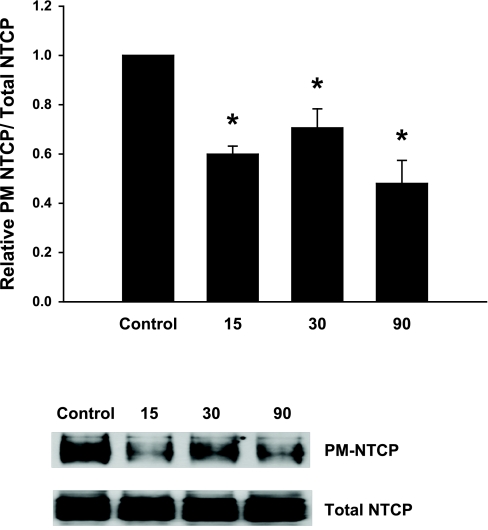

NO decreases plasma membrane NTCP in HuH-NTCP cells.

The effect of NO on plasma membrane NTCP was determined via a biotinylation method previously used by us to study translocation of NTCP (42). Treatment of HuH-NTCP cells with SNOC over a range of times (0–90 min) resulted in a significant decrease in the amount of NTCP present at the plasma membrane (Fig. 4). Total NTCP was not affected by SNOC treatment indicating that the expression of NTCP was unaffected. These data suggest that NO-induced noncompetitive inhibition of TC uptake is likely to be due to retrieval of NTCP from the plasma membrane.

Fig. 4.

NO alters the subcellular localization of NTCP. HuH-NTCP cells were treated with or without SNOC (1 mM) for 15, 30, or 90 min. Following treatment, plasma membrane (PM) proteins were selectively biotinylated and purified with streptavidin agarose beads. Those samples were then subjected to a NTCP immunoblot to determine the amount of NTCP present at the plasma membrane. Total NTCP levels were determined by performing a NTCP immunoblot of whole cell lysates. A typical immunoblot is shown at bottom. The results (means ± SE; n = 5) are presented as relative amounts of NTCP present at the plasma membrane normalized to total NTCP. The amount of NTCP present at the plasma membrane is significantly reduced by SNOC treatment at all the times tested compared with controls (*P < 0.05).

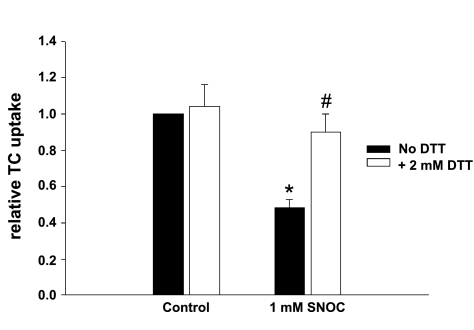

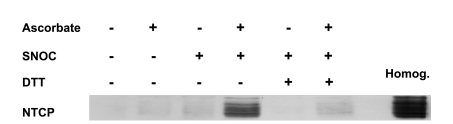

DTT reverses NO-mediated NTCP S-nitrosylation and inhibition of TC uptake.

One way NO exerts its actions is by binding to critical cysteine residues in a reversible process known as S-nitrosylation. It has been shown that the reducing agent dithiothreitol (DTT) can reverse the S-nitrosylation of proteins (34). Thus, if NO-mediated inhibition of TC uptake is due to NTCP S-nitrosylation, one would expect DTT to reverse the effect of NO on TC uptake and NTCP S-nitrosylation. To test this, HuH-NTCP cells were first treated with 1 mM SNOC for 30 min. Cells were then washed and treated with or without with 2 mM DTT for an additional 15 min before determining TC uptake and NTCP S-nitrosylation. Incubation with DTT alone had no effect on TC uptake (Fig. 5). However, SNOC-induced inhibition of TC uptake was reversed by DTT (Fig. 5). Treatment of HuH-NTCP cells with SNOC resulted in a marked increase in the S-nitrosylation of NTCP whereas levels of S-nitrosylated NTCP in control cells was barely detectable (Fig. 6), demonstrating NO-mediated NTCP S-nitrosylation in intact cells. SNOC-induced NTCP S-nitrosylation was completely reversed by DTT as evidenced by barely detectable NTCP signal in cells treated with DTT (Fig. 6). The ability of DTT to reverse NO-induced NTCP S-nitrosylation and inhibition of TC uptake suggest that NO-mediated S-nitrosylation of a critical cysteine residue(s) in NTCP is involved in NO-induced inhibition of TC uptake.

Fig. 5.

DTT treatment reverses NO-mediated inhibition of TC uptake. HuH-NTCP cells were treated with or without 1 mM SNOC for 30 min. After the SNOC treatment, cells were washed and then incubated with or without 2 mM DTT for another 15 min before determining TC uptake. Results are presented relative to the control samples treated without DTT (means ± SE; n = 5). Treatment with 1 mM SNOC inhibits TC uptake (*P < 0.05). DTT treatment resulted in a significant reversal of TC uptake compared with the 1 mM SNOC samples (#P < 0.05).

Fig. 6.

DTT treatment reverses NO-mediated S-nitrosylation of NTCP. HuH-NTCP cells were treated with or without 1 mM SNOC for 30 min. After the SNOC treatment, cells were washed and then incubated with or without 2 mM DTT for another 15 min before the biotin switch assay. Samples treated without ascorbic acid served as a negative control. A whole cell homogenate sample (Homog.) is included as a positive control. SNOC treatment results in the S-nitrosylation of NTCP whereas DTT reverses the S-nitrosylation of NTCP. This blot is representative of 4 independent experiments.

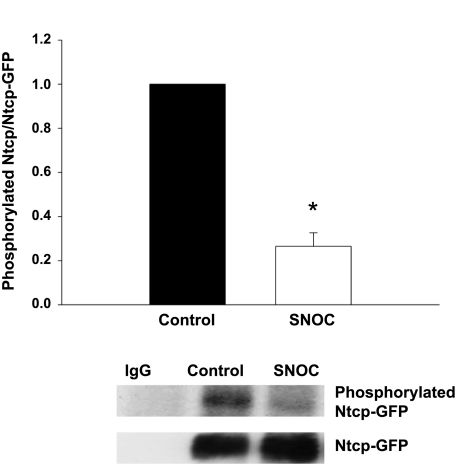

SNOC treatment reduces Ntcp phosphorylation.

NTCP/Ntcp is a phosphoprotein and nitric oxide has been shown to alter the phosphorylation of several proteins (28, 30, 43). To test whether SNOC treatment alters phosphorylation of NTCP/Ntcp, we transiently transfected HuH-NTCP cells with a Ntcp-GFP construct. Transfection with the fusion protein was necessary to avoid the heavy chain bands that interfere with detecting NTCP by Western blot. At 48 h posttransfection, cells were labeled with [32P]orthophosphate. The fusion protein was then immunoprecipitated and the degree of Ntcp phosphorylation was determined by SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. In control experiments, we determined that GFP was not phosphorylated (data not shown). The amount of Ntcp phosphorylation was then normalized by performing a GFP immunoblot on the same membrane to determine total Ntcp-GFP. Negative control immunoprecipitations showed that Ntcp-GFP was not immunoprecipitated with rabbit IgG. SNOC treatment showed a marked decrease in the amount of Ntcp-GFP phosphorylation (Fig. 7), raising the possibility that NO may inhibit kinases responsible for the phosphorylation of NTCP/Ntcp.

Fig. 7.

NO reduces Ntcp phosphorylation. HuH-NTCP cells were transfected with a Ntcp-GFP plasmid. At 48 h posttransfection the cells were labeled with [32P]orthophosphate. Phosphorylation status was determined by immunoprecipitating Ntcp-GFP, performing SDS-PAGE transferring proteins to nitrocellulose followed by autoradiography. Samples immunoprecipitated with rabbit IgG served as a negative control. Following autoradiography, membranes were subjected to green fluorescent protein (GFP) immunoblot to control for amount of Ntcp-GFP immunoprecipitated. The results (means ± SE, n = 4) are presented as relative amounts of phosphorylated Ntcp normalized to the total amount of Ntcp immunoprecipitated. A typical autoradiograph and GFP immunoblot are presented at bottom. The amount of Ntcp phosphorylation was significantly reduced following SNOC treatment (*P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The present study was designed to determine whether NO-induced inhibition of TC uptake involves S-nitrosylation of NTCP. A previous study had shown that rat Ntcp is inhibited with the NO donor, SNP (37). We extend these findings and demonstrate that human NTCP is also inhibited by NO in HuH-NTCP (Fig. 2). Kinetic analysis revealed that this inhibition was noncompetitive (Fig. 3, Table 1), which is also consistent with findings from rat hepatocytes (37). This earlier study in isolated rat hepatocytes, however, did not provide a molecular mechanism for the inhibition of TC uptake by NO nor did they test whether rat Ntcp is S-nitrosylated (37). Consistent with our kinetic data, we observed that NO treatment leads to a decrease in the amount of NTCP present at the plasma membrane (Fig. 4). This result led us to conclude that NO inhibits TC uptake by retrieving NTCP from the plasma membrane. We further investigated the role of S-nitrosylation in NO-mediated inhibition of TC uptake. Our studies showed that NO can S-nitrosylate NTCP. Furthermore, NO mediated S-nitrosylation of NTCP and inhibition of TC uptake were reversed by treatment with DTT, which is consistent with NO exerting an effect via modification of one or more cysteine residues. On the basis of these results we propose that inhibition of TC uptake by NO involves S-nitrosylation of NTCP. This study provides the first report, to our knowledge, that the activity of a hepatic transporter may be regulated by S-nitrosylation. The implication of this study in relation to endotoxemia and regulation of NTCP is discussed below.

During endotoxemia, a long-term decrease in bile flow is attributable to decreased transcription and expression of bile acid transporters such as Ntcp/NTCP and Mrp2/MRP2 (3, 5, 6, 37–39). However, bile flow and transporter function are also inhibited earlier than the repression of transporter expression. Using IL-6 or TNF as a cholestatic stimulus, researchers have observed an inhibition of TC uptake preceding downregulation of Ntcp mRNA (12, 44). In rat liver perfusion studies, LPS induces cholestasis due to an early retrieval of Mrp2 from the canalicular membrane whereas downregulation of Mrp2 mRNA is a later event (17). This short-term regulation of bile acid transporter function is thought to occur by altering the subcellular localization of transporters. Since only the plasma membrane localized Ntcp is active in bile salt uptake, Ntcp retrieval from the plasma membrane serves as another mechanism by which bile formation decreases during sepsis-associated cholestasis (11, 19). Indeed, both removal of Ntcp from the sinusoidal membrane and accumulation of intracellular deposits of Ntcp have been observed in cholestatic livers (11, 18). Our data indicate that S-nitrosylation of NTCP is associated with a decrease in the amount of NTCP present at the plasma membrane. Since endotoxemia is associated with increased NO formation, the associated cholestasis and decreased hepatic uptake of bile acids may result from S-nitrosylation of NTCP. Future studies will be needed to determine whether S-nitrosylation of NTCP occurs during early stages of endotoxemia.

Our study showed that S-nitrosylation of NTCP by NO is associated with altered subcellular localization of NTCP. It is becoming increasingly apparent that one way that S-nitrosylation regulates protein function is by controlling the subcellular localization of various proteins. Caspases are negatively regulated by S-nitrosylation and the majority of S-nitrosylated caspase-3 and caspase-9 is found in mitochondria (24–25). S-nitrosylation of GAPDH triggers binding to Siah (an E3 ubiquitin ligase), which in turn stimulates nuclear translocation and apoptosis (15). Thus our data demonstrating that S-nitrosylation of NTCP results in altering its subcellular localization provides another example of S-nitrosylation regulating localization of proteins.

It had previously been shown that cAMP-induced Ntcp translocation to the plasma membrane is associated with dephosphorylation of Ntcp at Ser-226 in the third cytoplasmic loop (2). We speculated that NO treatment, which decreases plasma membrane NTCP, might increase the phosphorylation of NTCP/Ntcp. Surprisingly, we found that NO treatment decreased phosphorylation of the transfected Ntcp-GFP fusion protein (Fig. 7). The mechanism by which NO may dephosphorylate NTCP/Ntcp is speculative at this point. NO has been shown to inhibit JNK1 kinase activity in isolated rat alveolar macrophages (28). S-nitrosylation of IKKβ inhibits Iκβ phosphorylation in alveolar type II epithelial cells (30). Another study demonstrated that NO can reduce phosphorylation of a β-adrenergic receptor phosphorylation by S-nitrosylation of G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (43). It is attractive to speculate that NO may inactivate a kinase responsible for phosphorylation of NTCP/Ntcp. Previous studies showed that cAMP-induced dephosphorylation of Ntcp involves activation of protein phosphatase 2B (41). Thus it is also possible that NO may activate a protein phosphatase leading to the dephosphorylation of NTCP/Ntcp. Further studies will be needed to define the mechanism by which NO dephosphorylates NTCP/Ntcp.

Our previous study showed that cAMP-induced Ntcp translocation to the plasma membrane is associated with dephosphorylation of Ntcp at Ser-226 in the third cytoplasmic loop (2). The present study showed that NO-mediated decrease in plasma membrane Ntcp are also associated with dephosphorylation of Ntcp. This apparent discrepancy may suggest that the translocation to or retrieval from the plasma membrane may be dependent on site specific dephosphorylation. On the other hand, it is possible that translocation/retrieval and dephosphorylation are two independent events. In that case, cAMP-induced activation of the PI3K signaling pathway may primarily mediate the translocation of the Ntcp to the plasma membrane (41), whereas the mechanism of Ntcp retrieval by NO remains to be investigated.

The present study demonstrates that NTCP is S-nitrosylated on one or more cysteine residues and S-nitrosylation of NTCP affects its function. Human NTCP has four cysteines that are conserved in rat, mouse, and rabbit (45). Mutation of cysteine 266 to alanine in either rat Ntcp or human NTCP produces a mutant Ntcp/NTCP that can still transport taurocholate (14, 45). Treatment with thiol-binding agents blocked wild-type NTCP uptake but did not inhibit uptake in a C266A mutant (14). These data indicate that mutation of C266 of NTCP does not abolish NTCP function but rather that C266 is a critical cysteine residue that is responsible for the sensitivity of NTCP to thiol-binding agents. Future studies will be needed to test whether C266 or other NTCP cysteines are susceptible to S-nitrosylation.

In summary, the present study showed that NO inhibits TC uptake by inducing retrieval of NTCP from the plasma membrane. The inhibition of TC uptake and most likely NTCP retrieval is due to NO-mediated S-nitrosylation of NTCP.

GRANTS

This work was supported by grants from Tufts Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine internal pilot grant (C. M. Schonhoff), Tufts Center for Gastroenterology Research on Absorptive and Secretory Processes (GRASP) Pilot Project (P30-DK-34928) (C. M. Schonhoff), Massachusetts Life Sciences Center New Investigator Award (MLSC-01) (C. M. Schonhoff), and an NIH grant DK-33436 (M. S. Anwer).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1. Anwer MS. Cellular regulation of hepatic bile acid transport in health and cholestasis. Hepatology 39: 581– 590, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anwer MS, Gillin H, Mukhopadhyay S, Balasubramaniyan N, Suchy FJ, Ananthanarayanan M. Dephosphorylation of Ser-226 facilitates plasma membrane retention of Ntcp. J Biol Chem 280: 33687– 33692, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blumrich M, Petzinger E. Membrane transport of conjugated and unconjugated bile acids into hepatocytes is susceptible to SH-blocking reagents. Biochim Biophys Acta 1029: 1– 12, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blumrich M, Petzinger E. Two distinct types of SH-groups are necessary for bumetanide and bile acid uptake into isolated rat hepatocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1149: 278– 284, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Burgstahler AD, Nathanson MH. NO modulates the apicolateral cytoskeleton of isolated hepatocytes by a PKC-dependent, cGMP-independent mechanism. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 269: G789– G799, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chand N, Sanyal AJ. Sepsis-induced cholestasis. Hepatology 45: 230– 241, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Corrales FJ, Ruiz F, Mato JM. In vivo regulation by glutathione of methionine adenosyltransferase S-nitrosylation in rat liver. J Hepatol 31: 887– 894, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dufour JF, Turner TJ, Arias IM. Nitric oxide blocks bile canalicular contraction by inhibiting inositol trisphosphate-dependent calcium mobilization. Gastroenterology 108: 841– 849, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Forrester MT, Foster MW, Benhar M, Stamler JS. Detection of protein S-nitrosylation with the biotin-switch technique. Free Radic Biol Med 46: 119– 126, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Foster MW, Hess DT, Stamler JS. Protein S-nitrosylation in health and disease: a current perspective. Trends Mol Med 15: 391– 404, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Geier A, Fickert P, Trauner M. Mechanisms of disease: mechanisms and clinical implications of cholestasis in sepsis. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 3: 574– 585, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Green RM, Whiting JF, Rosenbluth AB, Beier D, Gollan JL. Interleukin-6 inhibits hepatocyte taurocholate uptake and sodium-potassium-adenosinetriphosphatase activity. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 267: G1094– G1100, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hagenbuch B, Dawson P. The sodium bile salt cotransport family SLC10. Pflügers Arch 447: 566– 570, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hallen S, Fryklund J, Sachs G. Inhibition of the human sodium/bile acid cotransporters by side-specific methanethiosulfonate sulfhydryl reagents: substrate-controlled accessibility of site of inactivation. Biochemistry (Mosc) 39: 6743– 6750, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hara MR, Agrawal N, Kim SF, Cascio MB, Fujimuro M, Ozeki Y, Takahashi M, Cheah JH, Tankou SK, Hester LD, Ferris CD, Hayward SD, Snyder SH, Sawa A. S-nitrosylated GAPDH initiates apoptotic cell death by nuclear translocation following Siah1 binding. Nat Cell Biol 7: 665– 674, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jaffrey SR, Erdjument-Bromage H, Ferris CD, Tempst P, Snyder SH. Protein S-nitrosylation: a physiological signal for neuronal nitric oxide. Nat Cell Biol 3: 193– 197, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kubitz R, Wettstein M, Warskulat U, Haussinger D. Regulation of the multidrug resistance protein 2 in the rat liver by lipopolysaccharide and dexamethasone. Gastroenterology 116: 401– 410, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kuhlkamp T, Keitel V, Helmer A, Haussinger D, Kubitz R. Degradation of the sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP) by the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Biol Chem 386: 1065– 1074, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kullak-Ublick GA, Stieger B, Meier PJ. Enterohepatic bile salt transporters in normal physiology and liver disease. Gastroenterology 126: 322– 342, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lane P, Hao G, Gross SS. S-nitrosylation is emerging as a specific and fundamental posttranslational protein modification: head-to-head comparison with O-phosphorylation. Sci STKE 2001: re1, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Leslie EM, Watkins PB, Kim RB, Brouwer KL. Differential inhibition of rat and human Na+-dependent taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP/SLC10A1)by bosentan: a mechanism for species differences in hepatotoxicity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 321: 1170– 1178, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li J, Billiar TR. The anti-apoptotic actions of nitric oxide in hepatocytes. Cell Death Differ 6: 952– 955, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lopez-Sanchez LM, Corrales FJ, Barcos M, Espejo I, Munoz-Castaneda JR, Rodriguez-Ariza A. Inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis during induced cholestasis ameliorates hepatocellular injury by facilitating S-nitrosothiol homeostasis. Lab Invest 90: 116– 127, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mannick JB, Hausladen A, Liu L, Hess DT, Zeng M, Miao QX, Kane LS, Gow AJ, Stamler JS. Fas-induced caspase denitrosylation. Science 284: 651– 654, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mannick JB, Schonhoff C, Papeta N, Ghafourifar P, Szibor M, Fang K, Gaston B. S-Nitrosylation of mitochondrial caspases. J Cell Biol 154: 1111– 1116, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mukhopadhyay S, Ananthanarayanan M, Stieger B, Meier PJ, Suchy FJ, Anwer MS. Sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide is a serine, threonine phosphoprotein and is dephosphorylated by cyclic adenosine monophosphate. Hepatology 28: 1629– 1636, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Myers NC, Grune S, Jameson HL, Sawkat-Anwer M. cGMP stimulates bile acid-independent bile formation and biliary bicarbonate excretion. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 270: G418– G424, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Park HS, Huh SH, Kim MS, Lee SH, Choi EJ. Nitric oxide negatively regulates c-Jun N-terminal kinase/stress-activated protein kinase by means of S-nitrosylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 14382– 14387, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Perri RE, Langer DA, Chatterjee S, Gibbons SJ, Gadgil J, Cao S, Farrugia G, Shah VH. Defects in cGMP-PKG pathway contribute to impaired NO-dependent responses in hepatic stellate cells upon activation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 290: G535– G542, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Reynaert NL, Ckless K, Korn SH, Vos N, Guala AS, Wouters EF, van der Vliet A, Janssen-Heininger YM. Nitric oxide represses inhibitory kappaB kinase through S-nitrosylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 8945– 8950, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rockey DC, Shah V. Nitric oxide biology and the liver: report of an AASLD research workshop. Hepatology 39: 250– 257, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ruiz F, Corrales FJ, Miqueo C, Mato JM. Nitric oxide inactivates rat hepatic methionine adenosyltransferase in vivo by S-nitrosylation. Hepatology 28: 1051– 1057, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ryu SD, Yi HG, Cha YN, Kang JH, Kang JS, Jeon YC, Park HK, Yu TM, Lee JN, Park CS. Flavin-containing monooxygenase activity can be inhibited by nitric oxide-mediated S-nitrosylation. Life Sci 75: 2559– 2572, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schonhoff CM, Daou MC, Jones SN, Schiffer CA, Ross AH. Nitric oxide-mediated inhibition of Hdm2-p53 binding. Biochemistry (Mosc) 41: 13570– 13574, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schonhoff CM, Yamazaki A, Hohenester S, Webster CR, Bouscarel B, Anwer MS. PKC(35)-dependent and -independent effects of taurolithocholate on PI3K/PKB pathway and taurocholate uptake in HuH-NTCP cell line. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 297: G1259– G1267, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shneider BL, Fox VL, Schwarz KB, Watson CL, Ananthanarayanan M, Thevananther S, Christie DM, Hardikar W, Setchell KD, Mieli-Vergani G, Suchy FJ, Mowat AP. Hepatic basolateral sodium-dependent-bile acid transporter expression in two unusual cases of hypercholanemia and in extrahepatic biliary atresia. Hepatology 25: 1176– 1183, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Song IS, Lee IK, Chung SJ, Kim SG, Lee MG, Shim CK. Effect of nitric oxide on the sinusoidal uptake of organic cations and anions by isolated hepatocytes. Arch Pharm Res 25: 984– 988, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Spirli C, Fabris L, Duner E, Fiorotto R, Ballardini G, Roskams T, Larusso NF, Sonzogni A, Okolicsanyi L, Strazzabosco M. Cytokine-stimulated nitric oxide production inhibits adenylyl cyclase and cAMP-dependent secretion in cholangiocytes. Gastroenterology 124: 737– 753, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Takikawa H. Hepatobiliary transport of bile acids and organic anions. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 9: 443– 447, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Trauner M, Nathanson MH, Mennone A, Rydberg SA, Boyer JL. Nitric oxide donors stimulate bile flow and glutathione disulfide excretion independent of guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic [corrected] monophosphate in the isolated perfused rat liver. Hepatology 25: 263– 269, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Webster CR, Srinivasulu U, Ananthanarayanan M, Suchy FJ, Anwer MS. Protein kinase B/Akt mediates cAMP- and cell swelling-stimulated Na+/taurocholate cotransport and Ntcp translocation. J Biol Chem 277: 28578– 28583, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Whalen EJ, Foster MW, Matsumoto A, Ozawa K, Violin JD, Que LG, Nelson CD, Benhar M, Keys JR, Rockman HA, Koch WJ, Daaka Y, Lefkowitz RJ, Stamler JS. Regulation of beta-adrenergic receptor signaling by S-nitrosylation of G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 2. Cell 129: 511– 522, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Whiting JF, Green RM, Rosenbluth AB, Gollan JL. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha decreases hepatocyte bile salt uptake and mediates endotoxin-induced cholestasis. Hepatology 22: 1273– 1278, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zahner D, Eckhardt U, Petzinger E. Transport of taurocholate by mutants of negatively charged amino acids, cysteines, and threonines of the rat liver sodium-dependent taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide Ntcp. Eur J Biochem 270: 1117– 1127, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]