Abstract

Epithelial proliferation, critical for homeostasis, healing, and colon cancer progression, is in part controlled by epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). Proliferation of colonic epithelia can be induced by Citrobacter rodentium infection, and we have demonstrated that activity of tumor suppressor FOXO3 was attenuated after this infection. Thus the aim of this study was to determine the contribution of FOXO3 in EGFR-dependent proliferation of intestinal epithelia and colon cancer cell lines. In this study we show that, during infection with C. rodentium, EGFR was significantly phosphorylated in colonic mucosa and Foxo3 deficiency in this model lead to an increased number of bromodeoxyuridine-positive cells. In vitro, in human colon cancer cells, increased expression and activation of EGFR was associated with proliferation that leads to FOXO3 phosphorylation (inactivation). Following EGFR activation, FOXO3 was phosphorylated (via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt) and translocated to the cytosol where it was degraded. Moreover, inhibition of proliferation by overexpressing FOXO3 was not reversed by the EGFR signaling, implicating FOXO3 as one of the regulators downstream of EGFR. FOXO3 binding to the promoter of the cell cycle inhibitor p27kip1 was decreased by EGFR signaling, suggesting its role in EGFR-dependent proliferation. In conclusion, we show that proliferation in colonic epithelia and colon cancer cells, stimulated by EGFR, is mediated via loss of FOXO3 activity and speculate that FOXO3 may serve as a target in the development of new pharmacological treatments of proliferative diseases.

Keywords: EGFR, colon, FOXO3

proliferation of the intestinal epithelium is a highly efficient, ongoing process that under normal conditions results in complete epithelial renewal every 2–5 days. Normally, progression of the cell cycle is tightly regulated by multiple pathways that act as checks and balances, controlling proliferation. In diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), rapid proliferation maintains and repairs the barrier after injury (11). However, if proliferation becomes uncontrolled, it may shift the balance toward colon cancer development (14, 31).

Regulation of intestinal epithelial proliferation is in part regulated by EGFR activation by soluble growth factors present in the lamina propria (9). In the bound state, EGFR dimerizes, becomes phosphorylated, and allows downstream signaling to proceed (26). EGFR-dependent intestinal epithelial proliferation is important in IBD to repair tissue damage (13, 32), and administration of EGF-containing enemas can induce remission in patients with active disease (37). In colon cancer, EGFR expression and activity are increased (14, 31), and EGFR inhibitors have played an increasing therapeutic role (24). Downstream of EGFR, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and its target, Akt, are critical (33) for regulation of normal intestinal epithelial proliferation (36), whereas dysregulation of PI3K/Akt is associated with IBD and colon cancer (19, 43).

Tumor suppressor FOXO3, a member of the FOXO transcription factor family, localizes within the nucleus and binds DNA when active, regulating expression of genes that modulate metabolic state, cell cycle, and apoptosis (3, 5). FOXO3 activity decreases as a result of phosphorylation by several kinases, including PI3K/Akt (4). We have previously demonstrated in cytokine-treated colonic cells that PI3K negatively regulates FOXO3 (39). In colon carcinoma cell lines, FOXO3 activity is attenuated (20) and FOXO3 is closely connected with other regulators of proliferation and colon cancer such as p53, Puma, and members of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway (17, 45, 46). Thus we hypothesize that FOXO3 may be one of the mediators of EGFR-dependent intestinal proliferation.

We show using the Citrobacter rodentium-infected mouse model, in which EGFR is activated, that Foxo3 deficiency leads to increased proliferation. In vitro, in colon cancer cells, increased EGFR expression and activation elevated FOXO3 phosphorylation (inactive). Active FOXO3 appears to negatively regulate proliferation by binding to the promoter of cell cycle inhibitor p27kip1. In conclusion, FOXO3 functions downstream of EGFR and is a negative regulator of proliferation of normal intestinal epithelia and colon cancer cells lines.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and cell culture.

HT-29 human colon cancer cells [American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Manassas, VA] were propagated in McCoy's 5A medium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) supplemented with 10% FBS (GIBCO, Carlsbad, CA), and puromycin was used in selection of a clone with silenced EGFR (shRNA) (42). Human colon cancer cell lines, SW480 and SW620 (ATCC), cultured in RPMI with 10% FCS (GIBCO), were used as a model of differential EGFR expression (16). DLD1 human colon cancer cells were grown in RPMI-1640 (Mediatech, Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% FBS, and Geneticin (G418) was used in the selection of a subclone (DL23) stably transfected with inducible FOXO3 (23) (courtesy of Dr. Burgering, University Medical Center Utrecht, The Netherlands). FOXO3 expression was induced by addition of 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT, 100 nM; Sigma-Aldrich) for 24 h before experiments. Monolayers were serum deprived overnight prior to experiments.

Pharmacology.

EGF treatment (100 ng/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 or 60 min was used to investigate signaling pathways, and prolonged treatment of 2, 4, 6, and 24 h was used to investigate regulation of transcription, protein translocation, protein degradation, proliferation, and cell cycle distribution. Blockade of EGFR or PI3K was accomplished by using 4-[(3-bromophenyl) amino]-6, 7-dimethoxyquinazoline (AG1517, 1 μM; Calbiochem,) (29) or wortmannin (200 nM; Calbiochem) (38, 39). Inhibition of targeted molecules was accomplished by preincubation of monolayers with specific inhibitors 1 h prior to EGF treatment, and inhibitors were present during the treatment.

Immunofluorescent staining.

Monolayers were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100, and stained as previously described (38, 39). Anti-FOXO3 primary antibody (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) and Alexa 488-conjugated secondary antibody were used (Molecular Probes-Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Coverslips were mounted by use of Prolong Gold antifade reagent (Molecular Probes) and images were captured with a Nikon Confocal Microscope C1 and analyzed with EZ-C1 software (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Protein extraction.

Total protein was extracted from epithelial monolayers by using a lysis buffer (Cell Signaling) supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). Nuclear and cytosolic protein fractions were obtained with a NE-PER Pierce extraction kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and aliquots were stored at −80°C.

Immunoblot.

Total (40 μg), cytosolic (40 μg), or nuclear (8 μg) protein, from different experimental groups, were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad) as previously described (38, 39). Primary antibodies were against FOXO3 (Cell Signaling), phosphorylated FOXO3 (at Thr32) (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY), actin, Oct-1, EGFR, pEGFR, p27kip1, and phosphorylated Akt (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Secondary antibodies were linked to horseradish peroxidase (Cell Signaling) and visualized using ECL plus Western blotting detection reagents (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK). Each experiment was repeated three times and three samples were used per experimental group for densitometric and statistical analysis.

siRNA.

FOXO3 small interfering RNA (siRNA; 30 nM) or equal amounts of negative control oligonucleotide (Invitrogen) were incubated in 50 μl of Opti-MEM containing Lipofectamine RNAiMax (Invitrogen) for 20 min at room temperature. The complexes were then added to 90000 HT-29 cells plated in 12-well plates and kept at 37°C for 48 h. We have previously described under this condition that FOXO3 is silenced by 98% (38).

Cell proliferation assays.

Proliferation was quantified by MTS assay (Promega, Madison, WI). Colon cancer cells were plated on 96-well plates, 5,000 cells per well, and incubated with the experimental compounds. After 48 h, part of the medium was removed, and MTS solution was added for another 3 h at 37°C. During this time, MTS converts to a water-soluble formazan product that was detected at 490 nm using a Microplate Reader SPECTRAmax Plus (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Experiments were repeated three independent times and one representative experiment has been shown.

Cell cycle distribution.

Cell cycle distribution was assessed by flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson Labware, Mansfield, MA). Cells grown on six-well plates were harvested by trypsinization and fixed in 70% ice-cold ethanol overnight. On the following day cells were stained with propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated with RNase A (Sigma-Aldrich) for 3 h at room temperature. DNA content for 10,000 cells was expressed as the percentage of cells in G0/G1 through G2/M. Experiments were repeated three independent times.

Quantitative RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from experimental monolayers using the Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and converted to cDNA by using Superscript II Reverse Transcriptase (SuperScript First-Strand Synthesis Kit; Invitrogen). cDNA template, p27kip1 primers (forward 5′-CAA ATG CCG GTT CTG TGG AG-3′, reverse 5′-TCC ATT CCA TGA AGT CAG CGA TA-3′), and TaqMan probes (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) were used for RT-PCR (SmartCycler System; Sunnyvale, CA), under the following conditions: 95°C for 10 min, 45 cycles of 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 60 s, and a final step at 50°C for 5 min. Gene copy numbers were determined by the standard curve method.

ChIP assay.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Millipore, Temecula, CA). Monolayers were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde, incubated in SDS lysis buffer, and DNA was fragmented (between 200 and 1,000 bp) by sonication. Samples with equal amounts of protein were incubated with anti-FOXO3 antibody (Cell Signaling) at 4°C overnight, and the DNA-protein complexes were pelleted with protein G-agarose. Furthermore, DNA was separated from proteins by heating samples at 65°C for 4 h in 5 M NaCl, following proteinase K and phenol-chloroform treatment and precipitation. Prepared DNA was then used as a template for PCR with the following primers: p27kip1, forward 5′-GTC CCT TCC AGC TGT CAC AT-3′, reverse 5′-GGA AAC CAA CCT TCC GTT CT-3′; input (β-actin), forward 5′-CCA CAC TGT GCC CAT CTA CG-3′, reverse 5′-AGG ATC TTC ATG AGG TAG TCA GTC AG-3′. Experiments were repeated three independent times.

Animal studies.

For in vivo studies, wild-type (WT) or Foxo3-deficient mice were used. Breeders were provided by Dr. Stanford Peng (Roche Palo Alto, Palo Alto, CA). Maintenance, genotyping, and infection, carried out in accordance with approved animal care protocols, were described previously (39).

BrdU staining.

Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation into the S phase of the cell cycle was used as a marker of proliferation. Two hours prior to euthanasia, mice were injected with BrdU (50 mg/kg body wt, Invitrogen). Colons were fixed in 10% formalin and embedded in paraffin, and 5-μm sections were cut. After deparaffinization for 1 h at 65°C, sections were rehydrated, quenched with 10% hydrogen peroxide, and trypsinized. Tissue sections were incubated with biotinylated anti-BrdU antibody followed by streptavidin-peroxidase, diaminobenzidine, and hematoxylin for visualization.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed by Student's t-test and one-way ANOVA test (Graphpad Prism; Sigma) was used for multiple samples. Data were expressed as means ± SE. Differences were considered significant for P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Foxo3 deficiency in mice increases proliferation of colonocytes during C. rodentium infection.

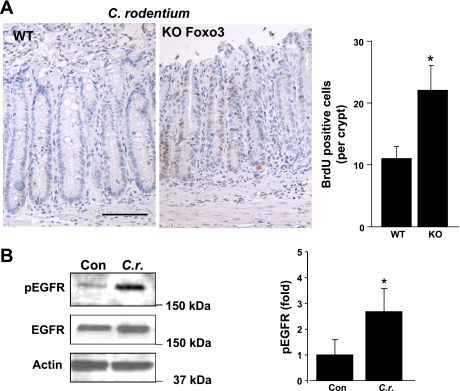

We have demonstrated that C. rodentium infection attenuates activity of FOXO3 in colonic cells (38). C. rodentium induces hyperproliferation of colonic epithelia (21), and the role of FOXO3 in intestinal proliferation is undefined. Thus, colonic epithelia of Foxo3-deficient mice infected with C. rodentium were assessed for proliferation. C. rodentium infected Foxo3-knockout (KO) mice have significantly increased numbers of BrdU-positive cells distributed along the crypt relative to WT mice (KO: 22 ± 6, WT: 11 ± 4 BrdU-positive cells per crypt) (Fig. 1A). Since proliferation of colonic epithelia is in part regulated by signals from EGFR (32, 35), we examined whether EGFR is activated by C. rodentium infection and might regulate FOXO3 activity. In C. rodentium-infected colonic mucosa, EGFR phosphorylation is increased 2.5-fold and total EGFR is slightly elevated in WT (Fig. 1B), which was similar to colonic mucosa of Foxo3-deficient mice (data not shown). Together, these data demonstrated that hyperproliferation of colonic epithelia in the C. rodentium mouse model is associated with loss of FOXO3 function and activation of EGFR.

Fig. 1.

Foxo3 deficiency in mice leads to increased proliferation of colonic epithelia. A: wild-type (WT) and Foxo3-deficient (KO) mice were infected with Citrobacter rodentium for 14 days to induce hyperproliferation of colonic epithelia (n = 8 for WT and KO). Two hours before being euthanized, mice were injected with bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU). Immunohistostaining revealed an increased number of BrdU-positive cells in colonic epithelia of Foxo3-deficient mice relative to WT mice, and the graph represents statistics of the BrdU-positive cells from 5 different fields with 25 crypts per mouse (*P < 0.05). B: C. rodentium infection induced EGF receptor (EGFR) phosphorylation in colonic mucosa. Protein from scraped colonic mucosa of control (Con) and C. rodentium (C.r.)-infected mice was analyzed for EGFR phosphorylation. Graph represents densitometric analysis (n = 3, *P < 0.05).

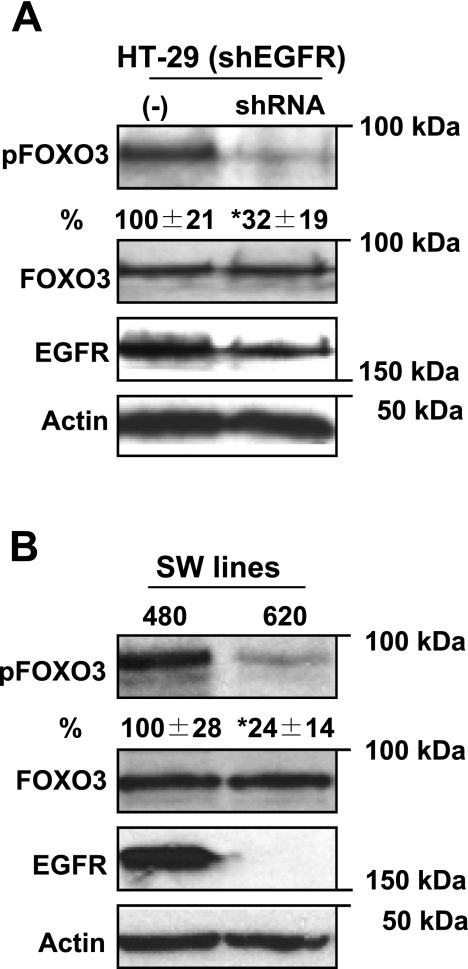

Decreased EGFR expression leads to attenuated FOXO3 phosphorylation in colon cancer cell lines.

On the basis of the above data, colonic proliferation is associated with activated EGFR and attenuated FOXO3 activity. We further assessed the relationship between EGFR and FOXO3 in human colon cancer cells. Initially, we examined whether EGFR expression affects FOXO3 activity by employing HT-29 cells with silenced EGFR (shEGFR) and attenuated proliferation (42). We compared FOXO3 phosphorylation, which represents inactive FOXO3, between cells with silent and WT EGFR. In cells with silenced EGFR, phosphorylated FOXO3 (at Thr32) was significantly decreased compared with controls (32 ± 19 vs. 100 ± 21% respectively), whereas total FOXO3 was the same (Fig. 2A). Thus data suggest that lower expression of EGFR and decreased proliferation is associated with reduced phosphorylated FOXO3 (inactive). Furthermore, additional colon cancer cell lines, SW480 and SW620, generated from the same patient, were used to test the role of EGFR in FOXO3 phosphorylation. SW620 cells have poor EGFR expression compared with SW480 (16). Both cell lines expressed the same amount of total FOXO3, whereas SW620 cells, with poor EGFR expression, had significantly less phosphorylated FOXO3 (Thr32) relative to SW480 (Fig. 2B). These data are consistent with the above data obtained in HT-29 cells, and, together, support that decreased EGFR expression and proliferation is associated with decreased phosphorylated FOXO3 (inactive) in colon cancer cells.

Fig. 2.

Decreased EGFR expression attenuates FOXO3 phosphorylation. A: protein from HT-29 cells with silent EGFR (shRNA) and adequate control were immunoblotted for phosphorylated and total FOXO3. HT-29 cells with silent EGFR (shEGFR) have less phosphorylated FOXO3 (inactive) relative to WT (−) EGFR expression. B: protein from colon cancer cell lines, SW480 and SW620 (SW lines), with different EGFR expression were analyzed for phosphorylated and total FOXO3. SW480 cells express significantly more EGFR than SW620 and have increased FOXO3 phosphorylation (inactive) relative to SW620. Densitometric analysis and percentage of phosphorylated FOXO3 were expressed below blots (n = 4, *P < 0.05).

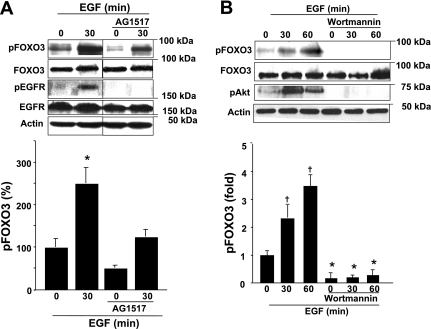

EGFR activity regulates FOXO3 phosphorylation via PI3K/Akt in colon cancer cells.

EGFR activation, induced by EGF binding (44), leads to EGFR phosphorylation and downstream signaling that results in increased proliferation (9). Thus we assessed the effect of EGFR activation on FOXO3 phosphorylation. An EGFR specific pharmacological inhibitor AG1517 was employed. EGF induced 2.5-fold increased FOXO3 phosphorylation at Thr32 site (inactive FOXO3) at 30 min, whereas AG1517 significantly decreased EGF induced FOXO3 phosphorylation (from 251 ± 14% to 127 ± 14% at 30 min) and decreased basal levels of phosphorylated FOXO3 (Fig. 3A). These data suggest that EGFR-induced proliferation promotes FOXO3 phosphorylation (inactivation) in colonic cancer cells.

Fig. 3.

Active EGFR induces FOXO3 phosphorylation via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway. A: protein from HT-29 monolayers, pretreated for 1 h with EGFR inhibitor AG1517, and treated with EGF was analyzed for FOXO3. EGF-induced FOXO3 phosphorylation at the Thr32 site is attenuated with AG1517. B: protein from HT-29 cells pretreated with the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin and EGF were analyzed for phosphorylated FOXO3 (at the Thr32 site that is PI3K dependent). A threefold increase in FOXO3 phosphorylation, induced by EGF, was inhibited by wortmannin. Graphs represent densitometric analysis (n = 4, *P < 0.05, †P < 0.01, ANOVA).

We have demonstrated that active PI3K/Akt is responsible for phosphorylation of FOXO3 by proinflammatory stimuli in intestinal epithelial cells (38, 39). Signals from EGFR activate the PI3K/Akt pathway (33), and the above data (Fig. 3A) showed that EGF induced FOXO3 phosphorylation at Thr32. This site is recognized as a phosphorylation target of the PI3K/Akt pathway (4). To further examine whether EGF-induced FOXO3 phosphorylation (inactivation) is PI3K/Akt dependent, we utilized the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin. EGF-stimulated Akt and FOXO3 phosphorylation (3-fold at Thr32) was inhibited by wortmannin (Fig. 3B). Taken together, these data show that EGFR-dependent PI3K activation leads to FOXO3 phosphorylation (inactivation) in colon HT-29 cells.

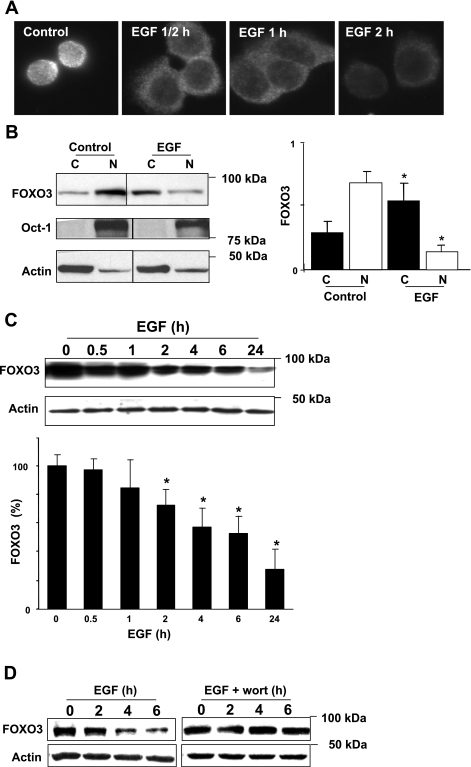

EGFR signals induce FOXO3 translocation and degradation in colon cancer cells.

Increased EGFR expression and activation, shown above, induces FOXO3 phosphorylation (inactivation). After being phosphorylated, FOXO3 translocates from the nucleus to the cytosol (3, 5). Thus we examined the localization of FOXO3 during EGF treatment. Immunofluorescence staining revealed FOXO3 translocation from the nucleus to the cytosol within the first 30 min of EGF treatment (Fig. 4A). This was confirmed in subcellular fractionation studies in which the ratio of nuclear to cytosolic FOXO3 decreased in controls from 2 to 0.4 following EGF treatment (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, during the course of EGF treatment, FOXO3 started to degrade within the first 30 min and degradation progressed throughout the course of treatment (significant differences were noted at 2 h of treatment) (Fig. 4C). EGFR-induced FOXO3 degradation is suppressed by inhibition of the PI3K pathway (Fig. 4D), confirming that PI3K is a critical mediator in EGFR-dependent FOXO3 inactivation (Fig. 3B). In summary, following EGFR activation, FOXO3 translocates from the nucleus to the cytosol and degrades in HT-29 cells.

Fig. 4.

EGFR activation leads to FOXO3 translocation to the cytosol and degradation in HT-29 cells. A: immunofluorescent staining for FOXO3 showed that, after EGF treatment, FOXO3 translocates from the nucleus to the cytosol within 30 min (magnification ×60). B: cytosolic (C) and nuclear (N) protein fractions from control and EGF-treated (for 2 h) HT-29 cells were separated and immunoblotted for total FOXO3. Oct-1 and actin were assessed to demonstrate equal loading and purity of fraction. There was a significant decrease in the ratio of nuclear vs. cytosolic FOXO3 after EGF treatment (*P < 0.05, ANOVA). C: EGF induced degradation of total FOXO3 in HT-29 cells for up to 24 h, and actin was evaluated to demonstrate equal loading (n = 4, *P < 0.05, ANOVA). D: inhibition of PI3K suppresses EGF-induced FOXO3 degradation. Protein from HT-29 cells pretreated with the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin (wort) and EGF for various times were analyzed for total FOXO3. Wortmannin inhibits EGF-induced FOXO3 degradation.

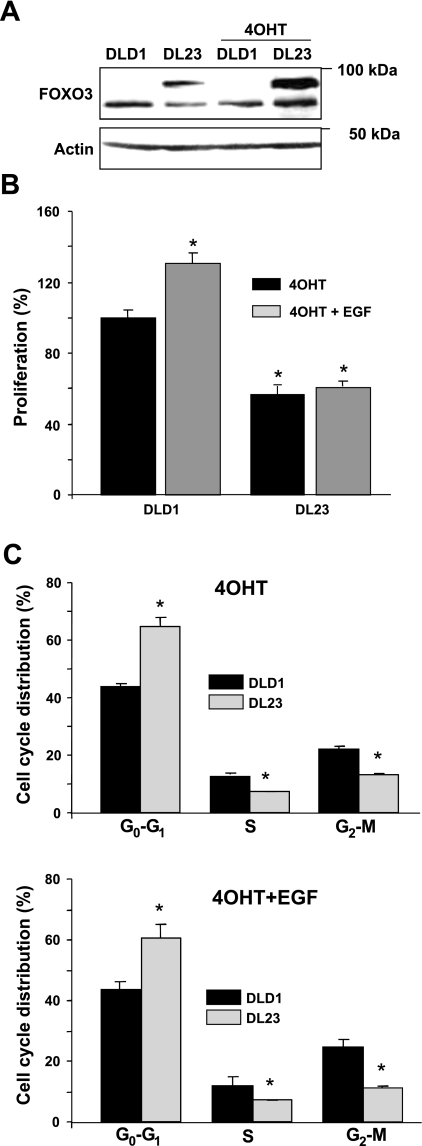

EGFR signals do not overcome inhibition of proliferation by overexpressed FOXO3.

Increased EGFR expression and activity stimulates proliferation of colonic epithelia (13, 14, 31, 32) whereas overexpression of FOXO3 inhibits proliferation by inducing cell cycle arrest (5, 10). Therefore, we hypothesize that EGFR stimulated proliferation leads to inhibition of FOXO3 that causes loss of cell cycle arrest. Another line of human colon cancer cells (DLD1 cells), stably transfected with FOXO3 under the 4-OHT-inducible promoter, was employed (Fig. 5A). These inducible DLD1 cells are known as DL23 cells (23). Overexpressed FOXO3 did not affect EGFR expression in DL23 cells (data not shown). Compared with control DLD1 cells transfected with the empty vector, EGF did not stimulate proliferation in FOXO3 overexpressing DL23 cells (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, EGF treatment did not overcome cell cycle arrest caused by overexpressed FOXO3 (Fig. 5C). Thus FOXO3 negatively regulates proliferation and EGFR signals stimulate proliferation in colonic epithelial cells, in part, by inactivating FOXO3.

Fig. 5.

Proliferation, inhibited by overexpressed FOXO3, is resistant to EGF. A: transgenic FOXO3 expression was induced in human colon cancer DL23 cells (stably transfected with FOXO3) by using 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT) treatments of 24 h; DLD1 cells expressing the empty vector were used as controls. B: in a parallel experiment, proliferation was determined by MTS assay. Proliferation was significantly attenuated in DL23 cells (black bar at right) when FOXO3 was overexpressed and was not stimulated with EGF (gray bar at right) as it was in control DLD1 cells (gray bar at left) (n = 8, *P < 0.05, ANOVA). C: cycle distribution between DLD1 and DL23 cells, treated with 4-OHT and EGF, was the same as in cells stimulated only with 4-OHT. DNA content was expressed as the percentage of cells in G0/G1 through G2/M (n = 6, *P < 0.05, ANOVA).

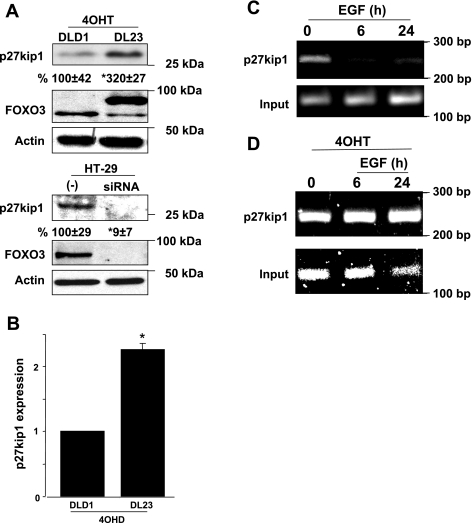

EGFR-dependent proliferation is mediated by FOXO3 regulation of cell cycle inhibitor p27kip1.

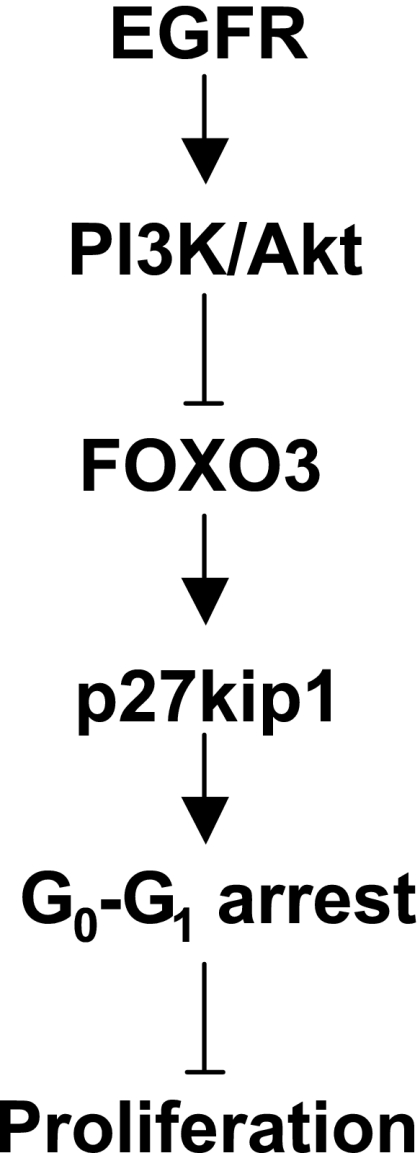

It has been demonstrated that active FOXO3 binds to the promoter region of the p27kip1 inhibitor of cell cycle progression (10, 23, 25). Thus we hypothesize that the proliferation stimulated by EGF is mediated by loss of FOXO3 activity and downregulation of the p27kip1 cell cycle inhibitor. When FOXO3 was overexpressed in DL23 cells, the expression of p27kip1 was increased (mRNA: 2.5-fold and protein: 3.2-fold), whereas FOXO3 knockdown in HT-29 cells resulted in a significant decrease in p27kip1 expression (Fig. 6, A and B). This suggests that active FOXO3 positively regulates p27kip1 expression. Transcriptional regulation, analyzed by ChiP assay, revealed that FOXO3 is bound to the promoter region of p27kip1 gene (at 110 bp), whereas EGF treatment leads to FOXO3 disassociation from the p27kip1 promoter (Fig. 6C). When cells overexpressed FOXO3, EGF did not disassociate FOXO3 from the p27kip1 promoter (Fig. 6D), which is in agreement with data showing that inhibited proliferation induced by overexpression of FOXO3 is resistant to EGF (Fig. 5, B and C). These data support that EGF negatively regulates FOXO3, which leads to downregulation of p27kip1, loss of cell cycle arrest, and thus increased proliferation (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

EGF impairs FOXO3-positive regulation of the cell cycle inhibitor p27kip1. A: FOXO3 overexpression was induced in DL23 cells with 4-OHT for 24 h. FOXO3 was silenced in HT-29 (siRNA) for 48 h and negative control (−) represents nonspecific oligonucleotides introduced to the cells. Efficiency of FOXO3 induction or silencing in both experiments is shown in the lower blots. Immunoblots show significantly increased p27kip1 expression in DL23 cells overexpressing FOXO3 and decreased expression in HT-29 cells with silent FOXO3. Densitometric analysis was shown as the percentage of change below blots (n = 4, *P < 0.05). B: total RNA (2 μg) extracted from DLD1 and DL23 cells treated with 4-OHT for 24 h was used for quantitative PCR. The relative expression level of p27kip1 transcript was increased in cells overexpressing FOXO3 (n = 3, *P < 0.05). C: chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChiP) assay showed lack of FOXO3 bound to the p27kip1 promoter region (110 bp) in HT-29 cells treated with EGF. D: overexpressed FOXO3 bound to p27kip1 promoter did not disassociate in presence of EGF. As a control (input), PCR was performed for actin.

Fig. 7.

Schematic representation of EGFR-FOXO3 cascade. The data presented here showed that signals from EGFR, via PI3K/Akt, negatively regulate FOXO3 that lead to downexpression of p27kip1 and loss of cell cycle arrest. This provides new insight into how EGFR stimulated proliferation is regulated in colonocytes.

DISCUSSION

Proliferation of intestinal epithelia is an efficient process critical for normal homeostasis, as well as in diseases such as IBD and colon cancer. In IBD, rapid proliferation repairs the barrier after injury (11), which is critical in breaking the cycle of inflammation-mediated tissue injury. On the other hand, uncontrolled proliferation leads to rapid colon cancer progression and may contribute to IBD-associated carcinogenesis (14, 31). Intestinal proliferation is in part controlled by signals from EGFR (32, 44), and, recently, pharmacological targeting of EGFR has been used for treatment of IBD and colon cancer (24, 37). Although the significance of EGFR in intestinal homeostasis and disease has been previously established, the cellular mechanisms downstream of EGFR are not completely understood. In this study, we have demonstrated that EGFR signals stimulate proliferation of colonic epithelia and colon cancer cells by negatively regulating tumor suppressor FOXO3. This knowledge will be important in the development of new pharmacological treatments of colon cancer and other intestinal proliferative diseases.

This study demonstrated that active FOXO3 negatively regulates proliferation of normal (nonneoplastic) colonic epithelia. As a model of colonic proliferation, mice were infected with C. rodentium, which is known to induce hyperproliferation of colonic epithelia (21). C. rodentium belongs to an attaching and effacing group of enteric bacteria (21). It has been demonstrated that enteropathogenic E. coli, a member of the same group of pathogens, induces EGFR activation and downstream signaling in vitro (34). This study showed that C. rodentium activates EGFR in colonic mucosa and that Foxo3 deficiency leads to an increased number of proliferative cells. In agreement with this finding, we previously demonstrated in control mice that nonproliferating colonocytes (i.e., midcrypt) have strong nuclear Foxo3 staining (active), whereas Foxo3 is cytosolic (inactive) in regions of rapid proliferation at the bases of the crypts (38). However, it is important to take into account that despite the increased number of proliferative cells, Foxo3 deficiency did not lead to increased crypt height, suggesting that Foxo3 deficiency may increase the overall rate of epithelial cell turnover.

Here we demonstrated in vitro that EGFR expression and activation tightly regulate FOXO3 activity in colon cancer cell lines. Increased EGFR expression and activation caused FOXO3 phosphorylation (inactivation) in colon cancer cells. In colon cancer cells with depleted EGFR, expression of FOXO3 was unchanged. It appears that although EGF induces FOXO3 degradation in experimental conditions, cells with depleted EGFR are able to somehow adjust by expressing similar basal levels of FOXO3. Yet these cancer cells are able to functionally decrease FOXO3 activity via posttranslational phosphorylation. The details of this compensation are still not fully understood.

It has been demonstrated that different growth factors inhibit FOXO3 activity, such as EGF in renal and mesangial cells (6, 22). Signals from EGFR are critical regulators of rapid proliferation of intestinal epithelia important in normal homeostasis as well as in pathology (7, 13, 14, 32, 44). Downstream of EGFR, activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway leads to FOXO3 phosphorylation (inactivation) in colon cancer cell lines. We have previously demonstrated similar roles of PI3K/Akt in regulation of FOXO3 activity by tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) and TLR4 in colon cancer cells (38, 39), suggesting that the PI3K/Akt pathway may be a critical regulator of FOXO3 function in colon cancer cells. It has been shown that PI3K/Akt mediates signals from EGFR and plays a critical role in regulation of normal intestinal epithelial proliferation (36), as well as in colon cancer (27). Downstream of EGFR, p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is required for EGFR function (15). Also, the PI3K pathway cooperates with Src signaling cascades (12) to stimulate EGFR proliferation of intestinal epithelial cells. We speculated that FOXO3 functioned downstream of p38; however, mechanisms of FOXO3 regulation by EGFR in colon cancer cells needed further investigation.

We sought to define the effect of FOXO3 on colon cancer cell proliferation and to determine the downstream target. Cell cycle arrest fostered by overexpression of FOXO3 was resistant to EGF, supporting the hypothesis that FOXO3 negatively regulates proliferation. Thus EGF proliferation is dependent on loss of FOXO3 activity. It is important to take into account that EGFR's signals utilize other cellular mechanisms to stimulate proliferation and that inability of EGF to overcome FOXO3 cell cycle arrest might be the result of extreme inhibition. Furthermore, it is possible that overexpressed FOXO3 affects other mediators in EGFR pathway, and thus, in part, indirectly inhibits EGFR mediated proliferation. Downstream, whereas active FOXO3 upregulates expression of the cell cycle inhibitor p27kip1 at the transcriptional level, EGF causes FOXO3 disassociation from p27kip1 promoter. It has been previously shown that FOXO3 regulates the cell cycle inhibitor p27kip1 in different cell lines (10, 23, 25). Cell cycle arrest is associated with abundant p27Kip1 expression (1, 8), whereas EGF reduces the level of p27Kip1 (2, 22). Thus we speculate that EGFR-FOXO3 proliferation is mediated via decreased p27kip1 cell cycle inhibitor expression and loss of G0-G1 arrest. This study demonstrated that the EGFR-PI3K/Akt-FOXO3-p27kip1 cascade plays a critical role in cell cycle progression of colon cancer; however, it is important to consider that other mechanisms dependent on p53 (30) or Wnt/β-catenin (18) may also be involved in this process.

Our data support that the EGFR pathway downregulates FOXO3 activity, which further leads to loss of cell cycle arrest and proliferation of intestinal epithelia and colon cancer cell lines. Thus targeting FOXO3 may be a rational therapeutic approach to treat intestinal proliferative diseases. It has already been shown that the FOXO family members may serve as therapeutic targets in various cancers by mediating the cytostatic and cytotoxic effects of chemotherapeutic drugs (40, 41, 47); however, this study demonstrated the significance of FOXO3 in intestinal pathology.

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by a Senior Investigator Award from the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America (CCFA#1953), a NorthShore University Healthsystem and University of Chicago Collaborative grant, and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases F32DK082134 fellowship award (C. R. Weber).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. Seema R. Gandhi and Jeffrey Brasky for assistance in preparing the manuscript. Also, we thank Dr. Burgering (University Medical Center, Utrecht, The Netherlands) for providing the DLD1 and DL23 cells and Dr. Stanford Peng (Roche Palo Alto LLC, Palo Alto, CA) for providing the Foxo3-deficient mice to establish our breeding colony.

REFERENCES

- 1. Agrawal D, Hauser P, McPherson F, Dong F, Garcia A, Pledger WJ. Repression of p27kip1 synthesis by platelet-derived growth factor in BALB/c 3T3 cells. Mol Cell Biol 16: 4327–4336, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alisi A, Spagnuolo S, Leoni S. Treatment with EGF increases the length of S-Phase after partial hepatectomy in rat, changing the activities of cdks. Cell Physiol Biochem 13: 239–248, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alvarez B, Martinez AC, Burgering BM, Carrera AC. Forkhead transcription factors contribute to execution of the mitotic programme in mammals. Nature 413: 744–747, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Birkenkamp KU, Coffer PJ. FOXO transcription factors as regulators of immune homeostasis: molecules to die for? J Immunol 171: 1623–1629, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Burgering BM, Kops GJ. Cell cycle and death control: long live Forkheads. Trends Biochem Sci 27: 352–360, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chahdi A, Sorokin A. Endothelin-1 couples betaPix to p66Shc: role of betaPix in cell proliferation through FOXO3a phosphorylation and p27kip1 down-regulation independently of Akt. Mol Biol Cell 19: 2609–2619, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ciardiello F, Damiano V, Bianco R, Bianco C, Fontanini G, De Laurentiis M, De Placido S, Mendelsohn J, Bianco AR, Tortora G. Antitumor activity of combined blockade of epidermal growth factor receptor and protein kinase A. J Natl Cancer Inst 88: 1770–1776, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Coats S, Flanagan WM, Nourse J, Roberts JM. Requirement of p27Kip1 for restriction point control of the fibroblast cell cycle. Science 272: 877–880, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cohen S, Carpenter G, King L., Jr Epidermal growth factor-receptor-protein kinase interactions. Co-purification of receptor and epidermal growth factor-enhanced phosphorylation activity. J Biol Chem 255: 4834–4842, 1980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Delpuech O, Griffiths B, East P, Essafi A, Lam EW, Burgering B, Downward J, Schulze A. Induction of Mxi1-SR alpha by FOXO3a contributes to repression of Myc-dependent gene expression. Mol Cell Biol 27: 4917–4930, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dignass AU. Mechanisms and modulation of intestinal epithelial repair. Inflamm Bowel Dis 7: 68–77, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dise RS, Frey MR, Whitehead RH, Polk DB. Epidermal growth factor stimulates Rac activation through Src and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase to promote colonic epithelial cell migration. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 294: G276–G285, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Egger B, Procaccino F, Lakshmanan J, Reinshagen M, Hoffmann P, Patel A, Reuben W, Gnanakkan S, Liu L, Barajas L, Eysselein VE. Mice lacking transforming growth factor alpha have an increased susceptibility to dextran sulfate-induced colitis. Gastroenterology 113: 825–832, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fichera A, Little N, Jagadeeswaran S, Dougherty U, Sehdev A, Mustafi R, Cerda S, Yuan W, Khare S, Tretiakova M, Gong C, Tallerico M, Cohen G, Joseph L, Hart J, Turner JR, Bissonnette M. Epidermal growth factor receptor signaling is required for microadenoma formation in the mouse azoxymethane model of colonic carcinogenesis. Cancer Res 67: 827–835, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Frey MR, Dise RS, Edelblum KL, Polk DB. p38 kinase regulates epidermal growth factor receptor downregulation and cellular migration. EMBO J 25: 5683–5692, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goetz M, Ziebart A, Foersch S, Vieth M, Waldner MJ, Delaney P, Galle PR, Neurath MF, Kiesslich R. In vivo molecular imaging of colorectal cancer with confocal endomicroscopy by targeting epidermal growth factor receptor. Gastroenterology 138: 435–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hoogeboom D, Essers MA, Polderman PE, Voets E, Smits LM, Burgering BM. Interaction of FOXO with beta-catenin inhibits beta-catenin/T cell factor activity. J Biol Chem 283: 9224–9230, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jin T, George Fantus I, Sun J. Wnt and beyond Wnt: multiple mechanisms control the transcriptional property of beta-catenin. Cell Signal 20: 1697–1704, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Katso R, Okkenhaug K, Ahmadi K, White S, Timms J, Waterfield MD. Cellular function of phosphoinositide 3-kinases: implications for development, homeostasis, and cancer. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 17: 615–675, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Khaleghpour K, Li Y, Banville D, Yu Z, Shen SH. Involvement of the PI 3-kinase signaling pathway in progression of colon adenocarcinoma. Carcinogenesis 25: 241–248, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Luperchio SA, Schauer DB. Molecular pathogenesis of Citrobacter rodentium and transmissible murine colonic hyperplasia. Microbes Infect 3: 333–340, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mahimainathan L, Ghosh-Choudhury N, Venkatesan BA, Danda RS, Choudhury GG. EGF stimulates mesangial cell mitogenesis via PI3-kinase-mediated MAPK-dependent and AKT kinase-independent manner: involvement of c-fos and p27Kip1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 289: F72–F82, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Medema RH, Kops GJ, Bos JL, Burgering BM. AFX-like Forkhead transcription factors mediate cell-cycle regulation by Ras and PKB through p27kip1. Nature 404: 782–787, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Modjtahedi H, Essapen S. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors in cancer treatment: advances, challenges and opportunities. Anticancer Drugs 20: 851–855, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nakamura N, Ramaswamy S, Vazquez F, Signoretti S, Loda M, Sellers WR. Forkhead transcription factors are critical effectors of cell death and cell cycle arrest downstream of PTEN. Mol Cell Biol 20: 8969–8982, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Olayioye MA, Neve RM, Lane HA, Hynes NE. The ErbB signaling network: receptor heterodimerization in development and cancer. EMBO J 19: 3159–3167, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Phillips WA, St, Clair F, Munday AD, Thomas RJ, Mitchell CA. Increased levels of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activity in colorectal tumors. Cancer 83: 41–47, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Polyak K, Kato JY, Solomon MJ, Sherr CJ, Massague J, Roberts JM, Koff A. p27Kip1, a cyclin-Cdk inhibitor, links transforming growth factor-beta and contact inhibition to cell cycle arrest. Genes Dev 8: 9–22, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Powell TJ, Ben-Bassat H, Klein BY, Chen H, Shenoy N, McCollough J, Narog B, Gazit A, Harzstark Z, Chaouat M, Levitzki R, Tang C, McMahon J, Shawver L, Levitzki A. Growth inhibition of psoriatic keratinocytes by quinazoline tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Br J Dermatol 141: 802–810, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rand A, Glenn KS, Alvares CP, White MB, Thibodeau SM, Karnes WE., Jr p53 functional loss in a colon cancer cell line with two missense mutations (218leu and 248trp) on separate alleles. Cancer Lett 98: 183–191, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rego RL, Foster NR, Smyrk TC, Le M, O'Connell MJ, Sargent DJ, Windschitl H, Sinicrope FA. Prognostic effect of activated EGFR expression in human colon carcinomas: comparison with EGFR status. Br J Cancer 102: 165–172, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Riegler M, Sedivy R, Sogukoglu T, Cosentini E, Bischof G, Teleky B, Feil W, Schiessel R, Hamilton G, Wenzl E. Epidermal growth factor promotes rapid response to epithelial injury in rabbit duodenum in vitro. Gastroenterology 111: 28–36, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rodrigues GA, Falasca M, Zhang Z, Ong SH, Schlessinger J. A novel positive feedback loop mediated by the docking protein Gab1 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in epidermal growth factor receptor signaling. Mol Cell Biol 20: 1448–1459, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Roxas JL, Koutsouris A, Viswanathan VK. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli-induced epidermal growth factor receptor activation contributes to physiological alterations in intestinal epithelial cells. Infect Immun 75: 2316–2324, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sheng G, Bernabe KQ, Guo J, Warner BW. Epidermal growth factor receptor-mediated proliferation of enterocytes requires p21waf1/cip1 expression. Gastroenterology 131: 153–164, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sheng H, Shao J, Townsend CM, Jr, Evers BM. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase mediates proliferative signals in intestinal epithelial cells. Gut 52: 1472–1478, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sinha A, Nightingale J, West KP, Berlanga-Acosta J, Playford RJ. Epidermal growth factor enemas with oral mesalamine for mild-to-moderate left-sided ulcerative colitis or proctitis. N Engl J Med 349: 350–357, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Snoeks L, Weber CR, Turner JR, Bhattacharyya M, Wasland K, Savkovic SD. Tumor suppressor Foxo3a is involved in the regulation of lipopolysaccharide-induced interleukin-8 in intestinal HT-29 cells. Infect Immun 76: 4677–4685, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Snoeks L, Weber CR, Wasland K, Turner JR, Vainder C, Qi W, Savkovic SD. Tumor suppressor FOXO3 participates in the regulation of intestinal inflammation. Lab Invest 89: 1053–1062, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sunters A, Fernandez de Mattos S, Stahl M, Brosens JJ, Zoumpoulidou G, Saunders CA, Coffer PJ, Medema RH, Coombes RC, Lam EW. FoxO3a transcriptional regulation of Bim controls apoptosis in paclitaxel-treated breast cancer cell lines. J Biol Chem 278: 49795–49805, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sunters A, Madureira PA, Pomeranz KM, Aubert M, Brosens JJ, Cook SJ, Burgering BM, Coombes RC, Lam EW. Paclitaxel-induced nuclear translocation of FOXO3a in breast cancer cells is mediated by c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase and Akt. Cancer Res 66: 212–220, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wali RK, Kunte DP, Koetsier JL, Bissonnette M, Roy HK. Polyethylene glycol-mediated colorectal cancer chemoprevention: roles of epidermal growth factor receptor and Snail. Mol Cancer Ther 7: 3103–3111, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wei J, Feng J. Signaling pathways associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov 4: 105–117, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wilson AJ, Gibson PR. Role of epidermal growth factor receptor in basal and stimulated colonic epithelial cell migration in vitro. Exp Cell Res 250: 187–196, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. You H, Yamamoto K, Mak TW. Regulation of transactivation-independent proapoptotic activity of p53 by FOXO3a. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 9051–9056, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yu J, Zhang L, Hwang PM, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. PUMA induces the rapid apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells. Mol Cell 7: 673–682, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zeng Z, Samudio IJ, Zhang W, Estrov Z, Pelicano H, Harris D, Frolova O, Hail N, Jr, Chen W, Kornblau SM, Huang P, Lu Y, Mills GB, Andreeff M, Konopleva M. Simultaneous inhibition of PDK1/AKT and Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 signaling by a small-molecule KP372–1 induces mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in acute myelogenous leukemia. Cancer Res 66: 3737–3746, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]