American crime policy took an unexpected turn in the latter part of the twenty-first century, entering a new penal regime. From the 1920s to the early 1970s, the incarceration rate in the United States averaged 110 inmates per 100,000 persons. This rate of incarceration varied so little in the United States and internationally that many scholars believed the nation and the world were experiencing a stable equilibrium of punishment.1 But beginning in the mid-1970s, the U.S. incarceration rate accelerated dramatically, reaching the unprecedented rate of 197 inmates per 100,000 persons in 1990 and the previously unimaginable rate of 504 inmates per 100,000 persons in 2008.2 Incarceration in the United States is now so prevalent that it has become a normal life event for many disadvantaged young men, with some segments of the population more likely to end up in prison than attend college.3 Scholars have broadly described this national phenomenon as mass incarceration.4

Often obscured by national trends are the profound variations in incarceration rates across states, cities, and especially local communities within cities. Like the geographically concentrated nature of criminal offending by individuals, a small number of communities bear the disproportionate brunt of U.S. crime policy’s experiment with mass incarceration.5 While the concept of “hot spots” for crime is widely acknowledged, the sources and consequences of incarceration’s “hot spots” are not understood as well. Although the inhabitants of such communities experience incarceration as a disturbingly common occurrence, for most other communities and most other Americans incarceration is quite rare. This spatial inequality in punishment helps explain the widespread invisibility of mass incarceration to the average American.

Motivated by this reality, our essay examines the spatial concentration of incarceration, focusing on its geographic manifestations in the quintessentially American city of Chicago. Assembling census data, crime rates, and court records into a common geographic referent, we explore rates of community-level incarceration from 1990 to 2006 to probe three general questions:

How does incarceration impact neighborhoods differentially? What is the nature of spatial inequality in imprisonment rates across communities?

What is the temporal trend? Have neighborhood patterns changed over time?

What are the key correlates? For example, how do community-level features such as the crime rate and the concentration of poverty relate to the intensity of incarceration, across time and neighborhoods?

Overall, we demonstrate that mass incarceration is a phenomenon that is experienced locally and that follows a stable pattern over time. Hot spots for incarceration are hardly random; instead, they are systematically predicted by key social characteristics. In particular, the combination of poverty, unemployment, family disruption, and racial isolation is bound up with high levels of incarceration even when adjusting for the rate of crime that a community experiences. These factors suggest a self-reinforcing cycle that keeps some communities trapped in a negative feedback loop. The stability and place-based nature of incarceration have broad implications for how we think about policy responses.

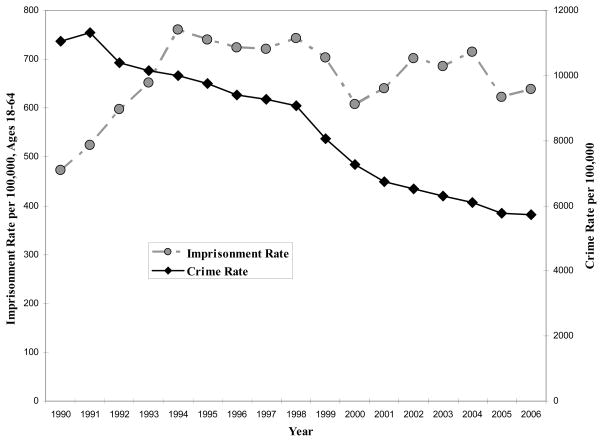

Is Chicago is a unique case or does it follow the general pattern of crime and punishment in late-twentieth-century America that has drawn attention from scholars? Figure 1 displays the temporal pattern of imprisonment juxtaposed with the overall crime rate for the period from 1990 to 2006. We measure the imprisonment rate by dividing the number of unique, Chicago-resident felony defendants sentenced to the Illinois Department of Corrections from the Circuit Court of Cook County by the number of Chicago inhabitants aged eighteen to sixty-four according to the Census. We use “at risk” adults in the denominator in order to rule out variations in the prevalence of children under age eighteen, who are not eligible for prison. Similarly, we exclude older residents because, while society is aging, very few prisoners are over the age of sixty-five. These data were gathered from the electronic records of the Circuit Court of Cook County. The crime rate is measured by the Uniform Crime Reports (UCR) “index” offenses (aggravated assault, forcible rape, murder, robbery, arson, burglary, larceny-theft, and motor vehicle theft) per 100,000 persons in Chicago.

Figure 1.

Imprisonment and Crime Trends in Chicago, 1990–2006

Mirroring national trends, the Chicago crime rate peaked at the beginning of the 1990s (11,320 offenses per 100,000 persons) and then declined throughout the remainder of the 1990s and into the early 2000s.6 As of 2006, the crime rate (5,721 offenses per 100,000 persons) in Chicago was the lowest it had been in at least the previous twenty years. Yet the imprisonment rate that began its rise in the 1970s (data not shown) continued to increase even after the crime rate peaked, climbing rapidly after 1990 and peaking in 1994 at 716 prisoners per 100,000 adult inhabitants. In just four years, the rate of imprisonment had increased 60 percent. It subsequently hovered near that all-time high, fluctuating between 600 and 700 prisoners per 100,000 adult inhabitants from 1994 to 2006. These Chicago trends, as depicted in Figure 1, are broadly consistent with trends in crime and incarceration throughout the United States.

Although the aggregate relationship between incarceration and crime is not the main focus of this paper, Figure 1 permits an overall assessment of the temporal connection. On the one hand, year-to-year changes in crime and imprisonment rates are not strongly correlated with each other when considering short temporal lags over the entire period. If mass incarceration functions as an effective criminal deterrent or tool of incapacitation, then crime decreases in years greater than t should follow imprisonment increases in year t. Yet the actual pattern observed in Figure 1 suggests that increases or decreases in the imprisonment rate do not always lead to short-term decreases or increases in the crime rate, and vice versa, after about 1994. On the other hand, the beginning of the crime drop in the 1990s corresponds to a rapid rise in incarceration. Although the number of cases is too small to reliably detect significance, the crime rate correlates −0.89 with incarceration from 1990 to 1994. Over the longer term of 1990 to 2006, the pattern yields a negative concurrent relationship (−0.47, p < 0.10); crime decreased steadily as the imprisonment rate increased and then maintained, more or less, a high rate. Therefore, the dynamic relationship between imprisonment and crime from 1990 to 2006 is generally negative. However, the pattern is complex, and it is not possible to draw conclusions about cause and effect.

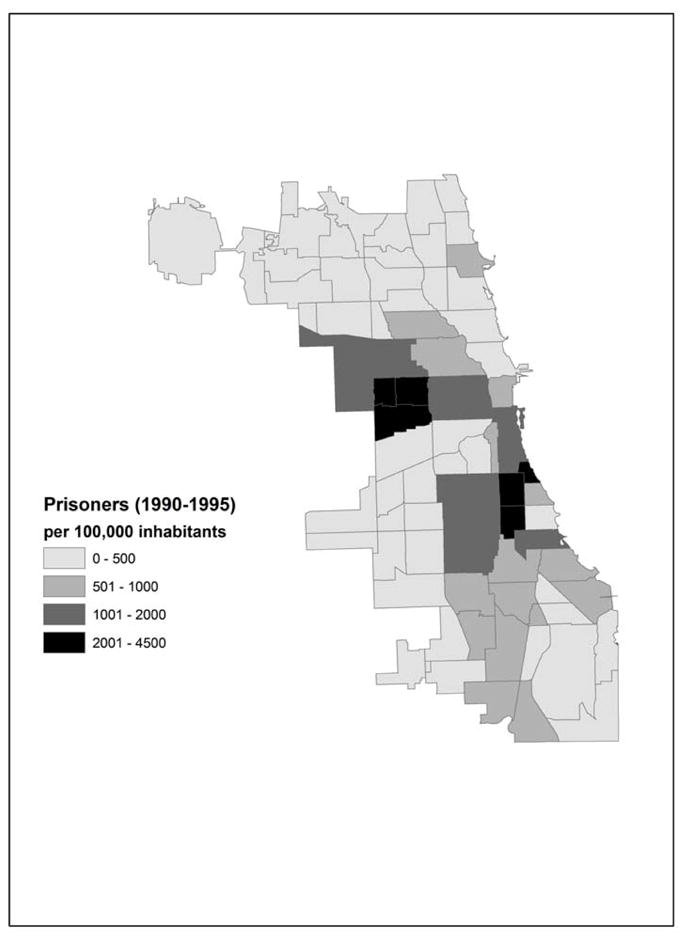

To what extent is mass incarceration concentrated? Unlike the temporal trends for imprisonment, the answer is unambiguous: punishment is distinctly concentrated by place. Figure 2 displays rates of imprisonment per 100,000 persons (aged eighteen to sixty-four) by community areas of Chicago for the period 1990 to 1995. Community areas average populations of approximately 38,000 persons; they are widely recognized by residents and, in most cases, have well-known geographic borders. Census tracts are nested within community areas and are smaller, averaging approximately 4,000 persons. The patterns for tracts (not shown) are nearly identical to community areas.

Figure 2.

Spatial Concentration of Incarceration in Chicago, 1990–1995

The basic pattern of concentration is stark. Large swaths of the city, especially in the southwest and northwest, remain relatively untouched by the imprisonment boom. In these areas, the incarceration rate ranges from nearly zero to less than 500 per 100,000 adult residents. By contrast, there is a dense and spatially contiguous cluster of areas in near-west and south-central Chicago that have rates of incarceration some eight times higher (or more). Note especially the line of communities stretching south from the Loop and west into to the suburban boundaries of the city (for example, the community of Austin) that produce a disproportionate share of prisoners.

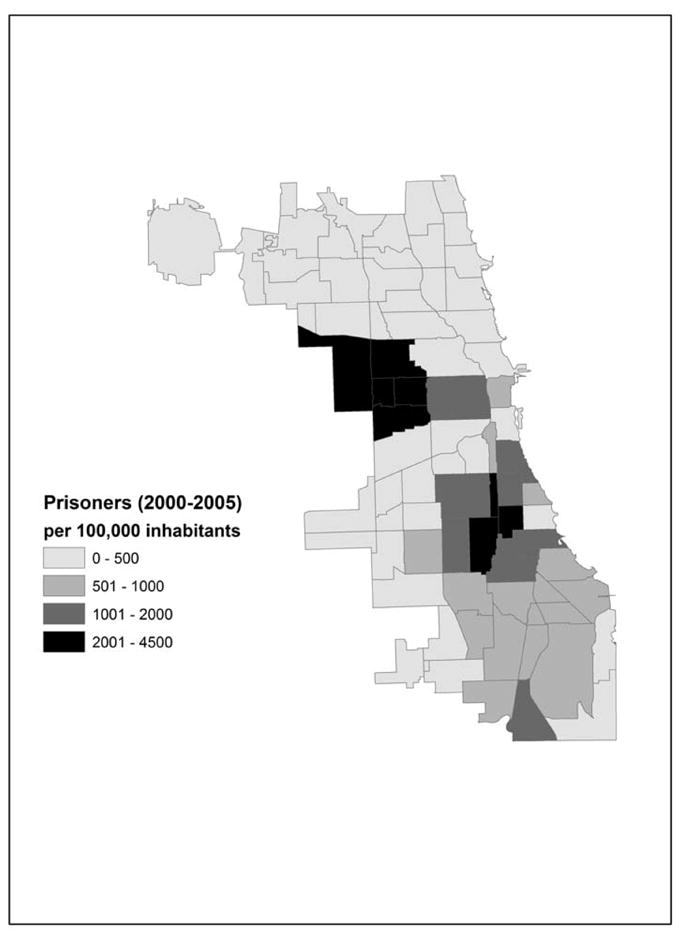

Does this pattern change over time? Despite a leveling-off in the overall intensity of punishment as foretold by Figure 1, there is a great deal of stability in the spatial logic of incarceration. Figure 3 presents imprisonment rates for the most recent period of available data, 2000 to 2005. As in 1990 to 1995, prisoners are primarily from the south and west sides of Chicago. In fact, at a glance, Figures 2 and 3 reveal very little difference in patterns of incarceration, even with the time gap. The simple correlation between the rates across time is greater than 0.90 for community areas and 0.86 for tracts (p < 0.01), an extremely high level of persistence. The Spearman’s correlation of rank order is 0.97 and 0.92, respectively, for community areas and tracts.

Figure 3.

Spatial Concentration of Incarceration in Chicago, 2000–2005

The main difference between the two time periods is that incarceration intensified its grip on the far west and south sides of the city. Not surprisingly, some areas that were already at the high end of the crime and incarceration distributions also saw improvements. Research, and the tendency of many social trends to “regress to the mean,” has shown that the highest-crime neighborhoods in Chicago have experienced the biggest crime drops.7 Nonetheless, the communities of Austin, East Garfield Park, and West Garfield Park (on the far west side) experienced the largest relative increases in imprisonment rates, approximately 50 percent, across the two time periods. By contrast, the areas of Oakland, Grand Boulevard, and Washington Park (on the near- to mid-south side) each experienced a decline of between 30 and 50 percent. Perhaps not coincidentally, some of these improving areas (especially Oakland and Grand Boulevard) saw large-scale changes or planned interventions that may explain the unexpectedly large declines, such as city investments in mixed-income housing, the demolition of high-rise public housing projects, and the steady in-migration of the African American middle class.8 Further examination of the consequences of these large-scale changes for the social and spatial organization of Chicago (the displacement of crime or the migration of offenders to other neighborhoods, for example) is beyond the scope of this paper but is currently being pursued in other studies.

Overall, the data in Figures 1–3 paint a picture of patterned stability and change in incarceration. Like the rest of the United States, Chicago has seen a boom in imprisonment, with rates increasing more than 50 percent from 1990 after a period of prior increases. These increases and subsequent temporal variations do not appear to track the crime rate closely, although in a broad sense it is clear that at the end of the twentieth century, crime approached record lows as incarceration hovered around its peak. As noted earlier, whether this occurrence is a causal effect of imprisonment on reducing crime or an artifact we cannot say. We can be certain, however, that against the march of time there is a fundamental inequality in the reach of incarceration across communities. Large areas of Chicago have escaped the brunt of the incarceration regime, while a small band of communities on the west, far west, south, and far south sides of Chicago are highly affected. This general pattern is stable, with already susceptible communities such as West Garfield Park and Austin on the west side undergoing dramatic growth beyond preexisting vulnerability. The implication of our finding is that the concept of “mass” incarceration is potentially quite misleading, for its instantiation is experienced at a highly local level.

What is it about high-rate “imprisoned” communities that explains their unequal experiences? We have demonstrated that imprisonment is not randomly inscribed across the urban landscape. Both logic and criminal justice “common wisdom” would suggest that the hot spots of punishment are those that generate the most crime. This is in part the case.

To take the most straightforward example, we calculated the rate of crime disaggregated by those forms that tend to generate the most public attention and that have been implicated in the imprisonment run-up: violence (assault, rape, and homicide), robbery, drug-related offenses, and burglary. At the community level, these crimes cluster together and correlate highly with later incarceration rates. For example, violence and drug crimes during the period 1995 to 2000 are both correlated at greater than 0.70 (p < 0.01) with incarceration rates in 2000 to 2005 across communities. Because prison sentencing does not occur instantaneously following an incidence of crime, we allowed for a lag effect by comparing two intervals of time that include multiple years, simultaneously allowing for variability in temporal lag patterns and reducing measurement error in both crime and incarceration rates. We also created a summary measure that combines information from the four major categories of crime. The results confirmed that all four crime rates correlate strongly with each other and form a single factor based on a principal components analysis. To capture the common variance, we calculated the first principal component, which is a simple linear combination of the four crime rates weighted by their association with the common factor. Put simply, the scale reflects the overall “crime propensity” of each community.

One might argue that arrest rates are a more direct measure of criminal offender production as opposed to the criminal offense production reflected in the crime rate. But high rates of citizen-reported crime are the more public face of victimization and demands for action against crime, and thus may be more relevant in terms of generating demand for punishment and reinforcing negative reputations about safety in select communities. Previous research has also shown that arrest rates and estimates of criminal offending rates are closely related to the crime rate, in large part because offenders tend to commit crimes relatively close to home.9 Consistent with this general argument, in the years 1998 and1999, the total arrest rate is correlated 0.78 (p < 0.01) with the total crime rate across neighborhoods in Chicago. We do not have arrest data across all relevant years in question that would allow us to pursue this issue further, thus we rely on the summary crime rate for the main analysis. We find that incarceration rates are very tightly connected at the neighborhood level with prior rates of crime. Specifically, consistent with our expectations, the crime factor correlates 0.72 (p < 0.01) with the later incarceration rate.

This pattern does not mean that the social features of communities can be set aside in thinking about communities’ risk for incarceration. There is a line of theoretical work arguing that concentrated inequality exacerbates existing patterns of criminal justice punishment. In particular, the attributions and perceptions of dangerousness attached to stigmatized and spatially concentrated minority groups have been hypothesized to increase the intensity of both unofficial beliefs about social disorder10 and official decisions to punish through incarceration.11 According to this argument, offenders from communities of concentrated disadvantage are themselves stigmatized and are more likely to be incarcerated when compared to those in less disadvantaged communities with similar crime rates.

We examined the broad contours of this thesis by estimating the relationship between dimensions of concentrated poverty and later incarceration, adjusting for the crime rate. Prior work on the Chicago data, and on national figures as well, has shown that correlated aspects of urban disadvantage tend to cluster, particularly the percentage of the population that is in poverty, unemployed, on welfare, and in single-parent, female-headed families. All of these factors are more prevalent in segregated African American areas (as indicated by the percentage of African Americans).12 Whether tracts or community areas, these social characteristics thus cluster together, defining a factor we label “concentrated disadvantage.”13 The correlation between concentrated disadvantage in 2000 and the incarceration rate in 2000 to 2005 is significant: 0.78 (p < 0.01). But disadvantage also co-varies with the crime rate; in fact, the correlation between disadvantage and the crime rate is equal to that of disadvantage and incarceration (0.78). Under these conditions, it is difficult to estimate independent associations other than with a simple model in which both the crime rate and disadvantage are allowed to predict later incarceration. Nevertheless, this finding suggests that both factors have explanatory relevance, especially at the tract level, where we have more cases and, as a consequence, greater statistical power.

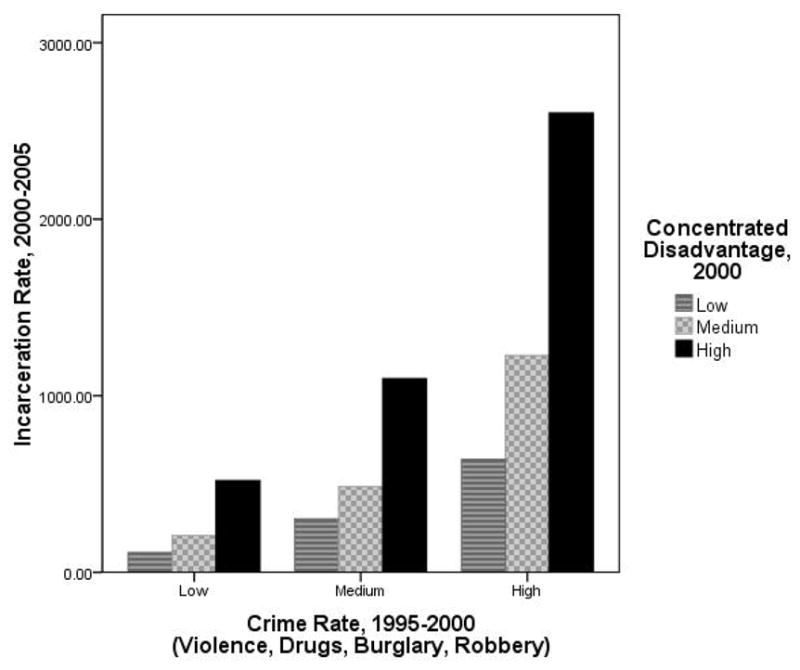

Figure 4 evaluates our claim, visually reflecting the magnitude of associations. The incarceration rate per 100,000 is graphed on the left axis. The bars refer to the indicators of the crime rate (combined six-year average of burglary, robbery, violence, and drugs) and the 2000 concentrated disadvantage scale, each split into equal thirds. At each level of the crime rate, incarceration rates increase monotonically with concentrated disadvantage. Note that at the very highest level of crime, those communities most “at risk” for punishment in the classic criminal-punishment sense are nonetheless clearly differentiated. In fact, communities that experienced high disadvantage experienced incarceration rates more than three times higher than communities with a similar crime rate. At all levels of concentrated disadvantage, crime rates significantly predict later incarceration as well. Thus it is not that incarceration is somehow “irrational,” rather it is increased in certain social contexts in ways that cannot be explained by crime. Analysis not shown confirmed that this pattern is maintained when racial composition (percent of the population that is African American) is entered as a separate control and not included in the disadvantage scale, and when the arrest rate of neighborhood residents (an indicator of offender production) is controlled.

Figure 4.

Incarceration by Concentrated Disadvantage and Crime, 1995–2005

We also explored the possibility of a reverse pathway of influence, whereby incarceration was specified as a predictor of future concentrated disadvantage independent of the crime rate leading up to that point. Our data (not shown) revealed that the incarceration rate in 1990 to 1995 strongly predicts concentrated disadvantage in 2000 when we control for the crime rate in 1995 to 2000 (p < 0.01), a strict test given that the crime rate is measured after the imprisonment rate and thus has presumably reaped any deflection from deterrent or incapacitation effects. The magnitude of the predictive association between incarceration and future disadvantage was similar to that of crime and disadvantage, and again, the relationship held when racial composition was considered as a separate control from the disadvantage factor.

What we appear to observe, then, is a mutually reinforcing social process: disadvantage and crime work together to drive up the incarceration rate. This combined influence in turn deepens the spatial concentration of disadvantage, even if at the same time it reduces crime through incapacitation. In such a reinforcing system with possible countervailing effects at the aggregate temporal scale, it is difficult, if not impossible, to estimate the overall net effect of incarceration. Moreover, one can argue that there is measurement error or misspecification in the nature of our crime rate control, a reality we acknowledge and have discussed above. But we have measured those offenses that are known to the criminal justice system and that have been shown to drive public opinion and, we suggest, incarceration decisions. Recent data from Chicago also show that arrest rates closely track crime rates and that offenders are highly constrained by spatial proximity and racial segregation in choosing crime locations.14 And when we directly control for the arrest rate of residents, the same results for concentrated disadvantage obtain.

Thus, although the entire pathway from crime to offender to prison sentence is indeed unobserved in our data, it is hard to imagine relevant characteristics that could diminish the significance of incarceration rates that differ by threefold or more. It seems more likely that while crime leads to incarceration up to a point, there is much more “input” to the system in the way of social cues and systematic community-level or contextual effects.15 In other words, crime and incarceration are partially decoupled at the community level. We suggest that the cluster of features reflected in concentrated disadvantage is a prime candidate for the source, but possibly also the consequence, of incarceration.

Mass incarceration has drawn much interest, but with few exceptions, little rigorous attention has been paid to the way that incarceration shapes and is shaped by local communities. Some claim that incarceration depletes social capital and thereby harms already disadvantaged communities.16 Others claim that deterrent or incapacitation effects of incarceration reduce crime and thereby improve human well-being, especially in disadvantaged communities that initially had the highest crime rates and have since witnessed the largest decreases in crime.17 As recently suggested by a systematic review of the available evidence on criminal recidivism, these apparently dueling arguments are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Imprisonment may be criminogenic even as the threat of punishment by confinement is a deterrent.18

We have investigated the spatial concentration of imprisonment in Chicago as well as the possibility that concentrated disadvantage is implicated in the spatial concentration of punishment beyond its contribution to criminal offending or arrest production. We do not claim to have set up a strict test of causality, and our data are limited as data always are. But the patterns we uncovered are consistent with our theoretical framework, are large in magnitude, and make conceptual sense at different levels of analysis. Specifically, while there seems to be little doubt that crime decreases have followed increased incarceration rates in recent years, the nature of this relationship is complex; aggregate trends in crime and imprisonment mask the magnitude of neighborhood concentration and the deep penetration of incarceration in high-rate communities (Figures 2–3). High levels of concentrated imprisonment, year after year, would seem unlikely to contribute to social-capital formation or other social processes that foster healthy communities.

We have also shown evidence consistent with the thesis that concentrated disadvantage strongly predicts later incarceration (adjusting for crime) and that incarceration strongly predicts later disadvantage (again adjusting for crime). The results are not simply attributable to the racial makeup of areas; although African Americans are both poorer and more likely to be incarcerated than whites or Hispanics, the association of concentrated disadvantage with incarceration is robust and therefore appears to be contextual rather than compositional in nature.

There are two implications from these findings. One is the likely reciprocal interaction whereby community vulnerability and incarceration are involved in a negative feedback loop. Disadvantaged communities are more likely to be highly incarcerated communities, which increases their likelihood of becoming even more disadvantaged in the future. The second implication concerns the flip side of prisoner production. If communities disproportionately produce prisoners, they will disproportionately draw them back upon release. After all, even when imprisonment rates have soared, most prisoners return to a home community.19 These twin feedback loops need further testing, but conceptually, they may help explain both the high degree of stability and the fundamental dilemma of highly imprisoned communities. Unless an alternative policy is implemented, the evidence suggests, a subset of communities will continue to produce concentrated disadvantage, concentrated crime, and concentrated imprisonment.

The logic of our essay is consistent with recent calls for a community-level approach to penal reform. Such an approach seeks to reintegrate offenders and help counteract the hardships–including high crime–that already disadvantaged neighborhoods face when unemployed ex-felons return home. The maps of Figures 2 and 3 paint a particularly stark picture of communities on the edge. Concentrated incarceration may have the unintended consequence of increasing crime rates through its negative impact on the labor market and social-capital prospects of former prisoners.20 What is more, evidence shows that neighborhood context plays a major role in the recidivism rates of ex-prisoners.21 The integration of prisoner release programs and efforts to build community capacity are important steps for policy.22 Along with policy reform, efforts to destigmatize and achieve justice for communities are crucial to overcoming the vicious cycle of crime production, victimization, incapacitation, and disadvantage.

Biographies

Robert J. Sampson, a Fellow of the American Academy since 2005, is the Henry Ford II Professor of the Social Sciences at Harvard University. His recent publications include Neighborhood Effects: Social Structure and Community in the American City (forthcoming from the University of Chicago Press), “Disparity and Diversity in the Contemporary City: Social (Dis)Order Revisited” (British Journal of Sociology, 2009), and “Moving to Inequality: Neighborhood Effects and Experiments Meet Social Structure” (American Journal of Sociology, 2008), which received the Jane Addams Award from the American Sociological Association.

Charles Loeffler is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Sociology at Harvard University and a former research associate at the U.S. Sentencing Commission.

References

- 1.Blumstein Alfred, Cohen Jacqueline. Theory of the Stability of Punishment. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology. 1973;64:198–207. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bureau of Justice Statistics. Prisoners in 2008. Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Justice; 2009. http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/glance/incrt.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pettit Becky, Western Bruce. Mass Imprisonment and the Life Course: Race and Class Inequality in U.S. Incarceration. American Sociological Review. 2004;69:151–169. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Western Bruce. Punishment and Inequality in America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clear Todd. Imprisoning Communities: How Mass Incarceration Makes Disadvantaged Neighborhoods Worse. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blumstein Alfred, Wallman Joel. The Crime Drop in America. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skogan Wesley. Police and Community in Chicago: A Tale of Three Cities. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pattillo Mary E. Black on the Block: The Politics of Race and Class in the City. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]; Sampson Robert J. Neighborhood Effects: Social Structure and Community in the American City. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2011. forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernasco Wim, Block Richard. Where Offenders Choose to Attack: A Discrete Choice Model of Robberies in Chicago. Criminology. 2009;47:93–130. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sampson Robert J. Disparity and Diversity in the Contemporary City: Social (Dis)Order Revisited. British Journal of Sociology. 2009;60:1–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-4446.2009.01211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sampson Robert J, Laub John H. Structural Variations in Juvenile Court Processing: Inequality, the Underclass, and Social Control. Law and Society Review. 1993;27:285–311. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Massey Douglas S, Denton Nancy. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]; Wilson William J. The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sampson Robert J, Raudenbush Stephen W, Earls Felton. Neighborhoods and Violent Crime: A Multilevel Study of Collective Efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bernasco, Block . Where Offenders Choose to Attack. pp. 93–130. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sampson . Disparity and Diversity in the Contemporary City. pp. 1–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Western, Punishment and Inequality in America; Clear, Imprisoning Communities

- 17.Skogan . Police and Community in Chicago. [Google Scholar]; Marvell Thomas, Moody Carlisle. Prison Population Growth and Crime Reduction. Journal of Quantitative Criminology. 1994;10:109–140. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagin Daniel S, Cullen Francis T, Jonson Cheryl Lero. Imprisonment and Reoffending. In: Tonry Michael., editor. Crime and Justice. Vol. 38. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2009. pp. 115–200. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Travis Jeremy. But They All Come Back: Facing the Challenges of Prisoner Reentry. Washington, D.C: Urban Institute Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Western . Punishment and Inequality in America. [Google Scholar]; Clear Todd R, Rose Dina R, Ryder Judith A. Incarceration and Community: The Problem of Removing and Returning Offenders. Crime and Delinquency. 2001;47:335–351. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hipp John R, Petersilia Joan, Turner Susan. Parolee Recidivism in California: The Effect of Neighborhood Context and Social Service Agency Characteristics. 2010 November48 forthcoming in Criminology. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clear, Rose, Ryder . Incarceration and Community. pp. 335–351. [Google Scholar]