Abstract

Activation of efferent renal sympathetic nerve activity (ERSNA) increases afferent renal nerve activity (ARNA), which then reflexively decreases ERSNA via activation of the renorenal reflexes to maintain low ERSNA. The ERSNA-ARNA interaction is mediated by norepinephrine (NE) that increases and decreases ARNA by activation of renal α1-and α2-adrenoceptors (AR), respectively. The ERSNA-induced increases in ARNA are suppressed during a low-sodium (2,470 ± 770% s) and enhanced during a high-sodium diet (5,670 ± 1,260% s). We examined the role of α2-AR in modulating the responsiveness of renal sensory nerves during low- and high-sodium diets. Immunohistochemical analysis suggested the presence of α2A-AR and α2C-AR subtypes on renal sensory nerves. During the low-sodium diet, renal pelvic administration of the α2-AR antagonist rauwolscine or the AT1 receptor antagonist losartan alone failed to alter the ARNA responses to reflex increases in ERSNA. Likewise, renal pelvic release of substance P produced by 250 pM NE (from 8.0 ± 1.3 to 8.5 ± 1.6 pg/min) was not affected by rauwolscine or losartan alone. However, rauwolscine+losartan enhanced the ARNA responses to reflex increases in ERSNA (4,680 ± 1,240%·s), and renal pelvic release of substance P by 250 pM NE, from 8.3 ± 0.6 to 14.2 ± 0.8 pg/min. During a high-sodium diet, rauwolscine had no effect on the ARNA response to reflex increases in ERSNA or renal pelvic release of substance P produced by NE. Losartan was not examined because of low endogenous ANG II levels in renal pelvic tissue during a high-sodium diet. Increased activation of α2-AR contributes to the reduced interaction between ERSNA and ARNA during low-sodium intake, whereas no/minimal activation of α2-AR contributes to the enhanced ERSNA-ARNA interaction under conditions of high sodium intake.

Keywords: kidney, sympathetic nerves, substance P, prostaglandin E2, angiotensin

the kidney has a rich supply of sympathetic nerves, which innervate all parts of the kidney (5). The kidney also has abundant afferent innervation; the fibers proceed from the kidney to the neuraxis and contain substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) as primary sensory neurotransmitters. The sensory nerve endings are located primarily in the renal pelvic wall (15, 21, 22, 24, 29). Sympathetic efferent nerve fibers and afferent sensory nerve fibers often run separately but intertwined in the same nerve bundles in the renal pelvic smooth muscle layer (22), providing anatomical support for a possible functional interaction between efferent renal sympathetic nerve activity (ERSNA) and afferent renal nerve activity (ARNA). Indeed, increasing ARNA by increasing renal pelvic pressure leads to a reflex decrease in ERSNA and increased natriuresis, i.e., a renorenal reflex response (26). The responsiveness of the renal sensory nerves is also modulated by ERSNA. Reflex increases and decreases in ERSNA increase and decrease ARNA, respectively (22, 24, 27). Taken together, there is strong evidence to support a negative feedback system, in which increases in ERSNA increase ARNA, which, in turn, decrease ERSNA via activation of the renorenal reflex.

Changes in ERSNA modulate ARNA by the release of the neurotransmitter norepinephrine (NE), which activates α1-adrenoceptors (AR) and α2-AR on renal sensory nerves, leading to increases and decreases in ARNA, respectively (22). The physiological importance of the ERSNA-induced increases in ARNA is underlined by the interaction being modulated by dietary sodium. A high-sodium diet enhances and a low-sodium diet reduces the ERSNA-induced increases in ARNA (24). Under the high-sodium dietary condition, enhancement of the ERSNA-induced increases in ARNA would increase the inhibitory renorenal reflex control of ERSNA, resulting in reduction of ERSNA to prevent or limit sodium retention. Conversely, in low-sodium dietary conditions, suppression of the ERSNA-induced increases in ARNA would result in increased ERSNA by reducing the renorenal reflex inhibition of ERSNA, eventually leading to sodium retention. The importance of the renorenal reflex-induced inhibition of ERSNA in the control of body fluid and sodium homeostasis was demonstrated in our previous studies, which showed that rats lacking intact afferent renal innervation are characterized by increased ERSNA, increased responsiveness of ERSNA to various sympathetic stimuli, and increased arterial pressure when fed a high-sodium diet (17, 25).

The current studies were performed to examine the mechanisms involved in the altered responsiveness of the renal sensory nerves to increases in ERSNA produced by varying sodium dietary intake. The renin-angiotensin (ANG) system is one of the possible mechanisms involved in the diet-dependent modulation of the interaction between ERSNA and ARNA. Our previous studies examining mechanisms involved in the activation of the renal mechanosensory nerves showed that stretching the renal pelvic wall leads to induction of COX-2 and increased renal pelvic synthesis of PGE2 (19, 20, 23). PGE2 increases the release of substance P, which increases ARNA via activation of the cAMP-PKA signal transduction pathway. Under low-sodium dietary conditions, the reduced responsiveness of the renal mechanosensory nerves to increased renal pelvic pressure involves increased activation of ANG II type 1 (AT1) receptors. Activation of AT1 receptors inhibits the PGE2-mediated activation of adenylyl cyclase by a pertussis toxin (PTX)-sensitive mechanism (16). Because the ERSNA-induced increases in ARNA are dependent on intact PG synthesis (22), we reasoned that a similar mechanism(s), i.e., increased activation of AT1-receptors, would be involved in the reduced ARNA responses to increases in ERSNA in rats on low-sodium diets. However, in our initial studies, the AT1 receptor antagonist losartan failed to enhance the responsiveness of the renal sensory nerves to increases in ERSNA.

In view of the inhibitory effects of NE-mediated activation of α2-AR on ARNA in rats on normal sodium diets (22), we then hypothesized that the reduced responsiveness of the renal sensory nerves to increases in ERSNA involves increased NE-mediated activation of renal pelvic α2-AR in rats fed a low-sodium diet. If so, we reasoned that the enhanced responsiveness of the renal sensory nerves to increases in ERSNA in rats on a high-sodium diet would involve decreased NE-mediated activation of renal α2-AR. We studied this hypothesis by examining the effects of renal pelvic administration of the α2-AR antagonist rauwolscine (2) on the increases in ARNA produced by reflex increases in ERSNA by thermal cutaneous stimulation. Because the reflex-mediated increases in ERSNA were associated with increases in arterial pressure (AP) and heart rate (HR), these studies were complemented with studies in which we examined the ARNA responses to renal pelvic administration of NE at a concentration that did not alter systemic hemodynamics. To examine whether the effects produced by reflex increases in ARNA and NE on ARNA involved presynaptic or postsynaptic effects of NE, additional experiments were performed in an isolated renal pelvic wall preparation from rats on high- and low-sodium diets.

We also carried out immunohistochemical studies to determine whether α2-ARs are located on or close to the sensory nerves and/or sympathetic nerves in the renal pelvic wall. We focused on the α2A- and α2C-AR subtypes because of their well-known expression on primary afferent neurons (7).

METHODS

The study was performed on male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 202–464 g (mean 284 ± 5 g). Two weeks before the study, rats were placed on either sodium-deficient pellets (Na+ = 1.6 meq/kg; Dyets, Bethlehem, PA) and tap water as drinking fluid (low-sodium diet, n = 115) or normal-sodium pellets with 0.9% NaCl solution as drinking fluid (high-sodium diet, n = 16) (20).

The experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and experiments were performed according to the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” from the National Institutes of Health.

Anesthesia was induced with pentobarbital sodium (0.2 mmol/kg ip; Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL).

In Vivo Studies

After induction of anesthesia, an intravenous infusion of pentobarbital sodium (0.04 mmol·kg−1·h−1) at 50 μl/min into the femoral vein was started and maintained throughout the course of the experiment. Arterial pressure was recorded from a catheter in the femoral artery. The left renal pelvis was perfused with vehicle or various perfusates, described below (Groups I–VII), throughout the experiment at 20 μl/min via a PE-10 catheter placed inside a PE-60 catheter located in the ureter. ERSNA and ARNA were recorded from the central and peripheral portions, respectively, of the cut ends of two adjacent left renal nerve branches, which were placed on bipolar silver wire electrodes. ERSNA and ARNA were integrated over 1-s intervals, the unit of measure being microvolts per second per 1 second. All data were collected at 500 Hz and averaged over 2 s. Postmortem renal nerve activity, assessed by crushing the renal nerve bundles proximal or distal to the recording electrode, was subtracted from all values of ERSNA and ARNA, respectively. Renal nerve activity was expressed in percentage of its baseline value during the control period (15–27).

Stimulation of renal sensory nerves.

Renal sensory nerves were stimulated by reflex-mediated increases in ERSNA, which were produced by placing the rat's tail in 47°C water (22, 24) or renal pelvic administration of NE. In all experimental groups, a 10-min control and a 10-min recovery period bracketed the experimental period.

Group I, low-sodium diet: effects of an AT1 receptor antagonist on the ARNA responses to reflex increases in ERSNA.

The experiments were divided into two parts. During each part, the rat's tail was placed in 47°C water during two 3-min experimental periods. Following each experimental period, the rat's tail was immediately placed in room-temperature water to quickly terminate the heat stimulation. Twenty minutes after the first recovery period, the renal pelvic perfusate was switched from vehicle to losartan (0.44 mM; n = 8) (16, 18). Ten minutes later, the control, experimental, and recovery periods were repeated.

Group II, low-sodium diet: effects of an α2-AR antagonist on the ARNA responses to reflex increases in ERSNA.

These experiments used a similar protocol as Group I, except rauwolscine, 0.1 μM (22), was administered into the renal pelvis (n = 14).

Group III, low-sodium diet: effects of an AT1 receptor antagonist plus an α2-AR antagonist on the ARNA responses to reflex increases in ERSNA.

These experiments used a similar protocol as Groups I and II, except losartan+rauwolscine were administered into the renal pelvis (n = 12).

Group IV, high-sodium diet: effects of an α2-AR antagonist on the ARNA responses to reflex increases in ERSNA.

The experiments performed in rats fed the high-sodium diet used a similar protocol as in Group II (n = 8).

Groups V–VII, low-sodium diet: effects of an AT1 receptor antagonist, an α2-AR antagonist, and an AT1 receptor antagonist plus an α2-AR antagonist on the ARNA responses to renal pelvic administration of NE.

The experiments were divided into three parts. During each part, 10 pM of NE, subthreshold concentration of NE for activation of renal sensory nerves in low-sodium diet rats (24), was administered into the renal pelvis during three 5-min experimental periods. In Group V (n = 7), the renal pelvic perfusate was switched from vehicle to 0.44 μM losartan at the end of the first recovery period. Five minutes later, the control, experimental, and recovery periods were repeated. At the end of the second recovery period, the renal pelvic perfusate was switched from losartan to losartan+rauwolscine. Five minutes later, the control, experimental, and recovery periods were repeated once more. In Group VI (n = 8), the experimental protocol was similar, except rauwolscine was administered instead of losartan at the end of the first recovery period. In Group VII (n = 5), only two control, experimental, and recovery periods were performed, the first part in the presence of vehicle and the second part in the presence of losartan+rauwolscine.

In Vitro Studies

To study whether the mechanisms involved in the altered responsiveness of the afferent renal nerves to NE in low- and high-sodium diets involve presynaptic or postsynaptic mechanisms, we examined the mechanisms of the NE-mediated release of substance P in an isolated renal pelvic wall preparation (14–24). NE increases substance P release by a PG-dependent mechanism (22). Therefore, we also examined whether the altered responsiveness of the renal sensory nerves to NE in rats fed low- and high-sodium diets was associated with changes in NE-induced PGE2 release.

The isolated renal pelvic wall preparation has previously been described in detail (14–24). In brief, following anesthesia renal pelvises dissected from the kidneys were placed in wells containing 400 μl HEPES buffer maintained at 37°C. Each well contained the pelvic wall from one kidney. Throughout the experiment, the incubation medium was replaced with fresh HEPES every 5 min. The incubation medium was collected in siliconized vials and stored at −80°C for later analysis of substance P and PGE2. After a 2-h equilibration period, the experiment was started with four 5-min control periods followed by one 5-min experimental period and four 5-min recovery periods. NE was added to the incubation bath to both pelvises during the experimental periods.

Group VIII, low-sodium diet: effects of an AT1 receptor antagonist on the NE-induced increases in substance P and PGE2.

One pelvis was incubated in HEPES buffer, and the other pelvis was incubated in HEPES buffer containing losartan (0.44 mM) throughout the control, experimental, and recovery periods. During the experimental period, both pelvises were exposed to NE at 6,250 pM (n = 10) or 1,250 pM (n = 6)—threshold and subthreshold concentrations for substance P release in rats on a low-sodium diet (24). Renal pelvic release of substance P and PGE2 into the incubation bath was measured throughout the experiment.

Group IX, low-sodium diet: effects of an α2-AR antagonist on the NE-induced increases in substance P and PGE2.

These experiments used a similar protocol as Group VIII, except one pelvis was incubated in HEPES buffer containing 0.1 μM rauwolscine instead of losartan. During the experimental period, both pelvises were exposed to NE at 6,250 pM (n = 4), 1,250 pM (n = 8), or 250 pM (n = 8).

Groups X and XI, low-sodium diet: effects of an AT1 receptor antagonist plus an α2-AR antagonist on the NE-induced increases in substance P and PGE2.

One pelvis was incubated in HEPES buffer containing losartan (n = 8) or rauwolscine (n = 16), and the other pelvis was incubated in HEPES buffer containing losartan+rauwolscine throughout the control, experimental, and recovery periods. During the experimental period, both pelvises were exposed to NE at 250 pM.

Group XII, high-sodium diet: effects of an α2-AR antagonist on the NE-induced increases in substance P and PGE2.

These experiments used a similar protocol as Group IX. During the experimental period, both pelvises were exposed to NE at 2 pM, a subthreshold concentration for substance P release in rats on a high-sodium diet (24).

Immunohistochemistry.

The immunohistochemical procedures have been previously described in detail (15, 21, 22, 24). In brief, anesthetized male Sprague-Dawley rats fed a low- or high-sodium diet were transcardially perfused with calcium-free Tyrode solution followed by phosphate-buffered (0.1 M, pH 7.4) fixative containing 4% wt/vol paraformaldehyde and 0.2% wt/vol picric acid. The kidneys were quickly dissected, postfixed in fixative for 90 min, and stored in 10% sucrose at 4°C. Fourteen-micrometer-thick sections were cut on a cryostat and thaw-mounted onto gelatin-coated slides. All primary antibodies were incubated for 24 h at 4°C.

The sections were incubated with antisera against α2A-AR or α2C-AR [rabbit 1:2,000 (45)]. Immunoreactivity was visualized using the tyramide signal amplification system (TSA-Plus: PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Waltham, MA). After completion of the protocol for TSA for detection of α2A-AR and α2C-AR, the tissue sections were incubated with antiserum for CGRP (mouse; 1:400; Drs. J. H. Walsh and H. C. Wong), a marker for sensory nerves, or the NE transporter (NE-t) (rabbit; 1:500; HPA004063, www.proteinatlas.org) (22), a marker for sympathetic nerves, and processed by the indirect immunofluorescence technique.

The specificity of the antisera for α2A-AR and α2C-AR was tested by preincubation of the primary antisera with an excess amount (10−5 M) of the fusion protein used as immunogen and by labeling cultured Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells with antisera against α2A-AR or α2C-AR. These CHO cells had been transfected to express human α2A-AR or α2C-AR (36) or represented wild-type (WT) CHO cells devoid of α2-AR expression.

The tissue sections were examined using a Nikon Eclipse E600 fluorescence microscope (Tokyo, Japan) equipped with epifluorescence and the appropriate filter combinations. Photographs were taken with a Hamamatsu ORCA-ER C4762-80 digital camera (Hamamatsu City, Japan) using Hamatsu photonics Wasabi software. For confocal analysis, a Radiance Plus confocal laser scanning system (Bio-Rad, Hemel Hemstead, UK) installed on a Nikon Eclipse E600 fluorescence microscope was used. Digital images from the microscopy were optimized for image resolution, brightness, and contrast, and color images were merged using Adobe Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA).

Drugs and Reagents

Substance P antibody (IHC 7,451) was acquired from Peninsula Laboratories (San Carlos, CA) and PGE2 from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI). All other reagents/chemicals were from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise stated. NE was dissolved in 0.1% ascorbic acid in incubation buffer or 0.15 M NaCl. All other agents were dissolved in incubation buffer (in vitro studies) or 0.15 M NaCl (in vivo studies).

Analytical Procedures

Concentrations of substance P and PGE2 in the incubation medium were measured by ELISA, as previously described in detail (14–24).

Statistical Analysis

In vivo, increases in ERSNA, ARNA, mean AP (MAP), and HR produced by placing the rat's tail in warm water were evaluated by calculating the area under the curve of each parameter vs. time, with baseline being the average value of each control period. Likewise, the ARNA responses to NE were calculated as the area under the curve of ARNA vs. time. In vitro, the release of substance P and PGE2 during the experimental period was compared with the substance P and PGE2 release during the control and recovery periods. Because not all data were normally distributed (D'Agostino and Pearson, omnibus normality tests), nonparametric analysis methods were used. The data were analyzed by Wilcoxon signed rank test and Friedman one-way ANOVA with repeated measures followed by Dunn's multiple-comparison test (GraphPad Prism 5.03, GrapPad Software, La Jolla, CA). A significance level of 5% was chosen. Data in the text and figures are expressed as means ± SE.

RESULTS

In Vivo Studies

Similar to our previous studies (24), placing the rat's tail in warm water resulted in reversible increases in MAP, HR, ERSNA, and ARNA that were of a greater magnitude in rats fed a high-sodium diet than in rats fed a low-sodium diet, although the differences in the ERSNA responses to thermal cutaneous stimulation between the high- and low-sodium diet did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.054) in the current studies (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effects of thermal cutaneous stimulation on MAP, HR, ERSNA, and ARNA in rats fed a low- and high-sodium diet during vehicle administration

| Low-Sodium Diet | High-Sodium Diet | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 33 | 8 |

| ΔMAP, mmHg/s | 3370 ± 260* | 5220 ± 920*† |

| ΔHR, beats·min−1·s | 22,010 ± 2390* | 35,090 ± 6650*† |

| ΔERSNA, %·s | 7920 ± 860* | 12,910 ± 3780* |

| ΔARNA, %·s | 2220 ± 450* | 5670 ± 1260*‡ |

Responses of mean artierial pressure (ΔMAP), heart rate (ΔHR), efferent renal sympathetic nerve activity (ΔERSNA) and afferent renal nerve activity (ΔARNA) are expressed as area under the curve of MAP, HR, ERSNA, and ARNA, respectively, vs. time.

P < 0.01 vs. baseline;

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01 vs. low-sodium diet.

Groups I–III, low-sodium diet: effects of an AT1 receptor antagonist and an α2-AR antagonist alone and in combination on the ARNA responses to reflex increases in ERSNA.

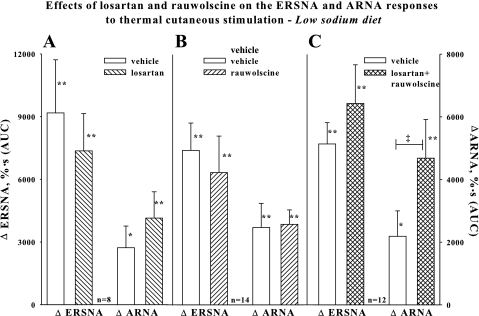

Because endogenous ANG plays an inhibitory role in the activation of renal mechanosensory nerves by increased renal pelvic pressure (18) in rats fed a low-sodium diet, we reasoned that losartan would enhance the suppressed ARNA responses to increases in ERSNA in rats on a low-sodium diet. However, renal pelvic perfusion with losartan failed to enhance the ARNA responses to increases in ERSNA, as shown in Fig. 1A. In view of the inhibitory effects of the NE-mediated activation of α2-AR on ARNA in rats fed a normal-sodium diet (22), we then hypothesized that an α2-AR antagonist would enhance the ARNA responses to increases in ERSNA. In contrast to our previous findings in rats on a normal-sodium diet (22), renal pelvic perfusion with rauwolscine had no effect on the ARNA responses to increases in ERSNA (Fig. 1B). Because rats on a normal-sodium diet are characterized by low endogenous ANG (4, 12), we then examined whether rauwolscine would increase the responsiveness of the afferent renal nerves in the presence of losartan. As shown in Fig. 1C, renal pelvic perfusion with a combination of losartan and rauwolscine enhanced the increases in ARNA produced by placing the rat's tail in 47°C water without affecting the increases in ERSNA.

Fig. 1.

In vivo low-salt diet. Effects of renal pelvic administration of vehicle (open bar) and losartan, 0.44 mM, (hatched bar) (A), rauwolscine, 0.1 μM, (hatched bar) (B), or losartan+rauwolscine (cross-hatched bar) (C) on the increases in ERSNA and ARNA produced by placing the rat's tail in 47°C water. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. baseline. ‡P < 0.01, ARNA responses to thermal cutaneous stimulation in the absence and presence of renal pelvic perfusion with losartan+rauwolscine. ΔERSNA, efferent renal sympathetic nerve activity response; ΔARNA, afferent renal nerve activity response; AUC, area under the curve of RNA vs. time.

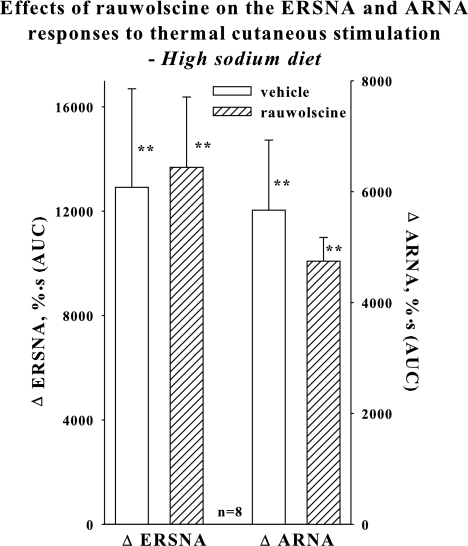

Group IV, high-sodium diet: effects of an α2-AR antagonist on the ARNA responses to reflex increases in ERSNA.

Because our findings in rats on a low-sodium diet suggested important inhibitory roles for both α2-AR and AT1 receptors in the ERSNA-induced increases in ARNA, we next examined the role of α2-AR in the activation of renal sensory nerves in rats fed a high-sodium diet, a physiological condition of low endogenous renal ANG levels (5, 12, 16). In contrast to our findings in rats on a low-sodium diet treated with losartan, rauwolscine had no effect on the ERSNA-induced increases in ARNA (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

In vivo high-salt diet: Effects of renal pelvic administration of vehicle (open bar) and rauwolscine (hatched bar) on the increases in ERSNA and ARNA produced by placing the rat's tail in 47°C water. **P < 0.01 vs. baseline.

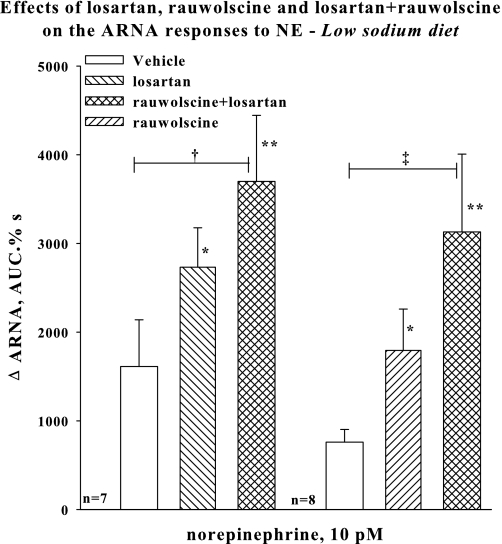

Groups V–VII, low-sodium diet: effects of an AT1 receptor antagonist and an α2-AR antagonist alone and in combination on the ARNA responses to renal pelvic administration of NE.

To minimize possible central and hemodynamic effects produced by reflex ERSNA modulating the responsiveness of the renal sensory nerves, we examined the effects of NE administered directly into the renal pelvis at concentrations that did not alter MAP. In the presence of either renal pelvic perfusion with losartan or rauwolscine alone, renal pelvic perfusion with 10 pM NE increased ARNA (Fig. 3). The increase in ARNA produced by 10 pM NE in the presence of vehicle did not reach statistical significance. The increases in ARNA produced by NE in the presence of rauwolscine or losartan were not different from the ARNA responses to NE in the presence of vehicle. In contrast, in the presence of renal pelvic perfusion with losartan+rauwolscine, NE resulted in increases in ARNA that were greater than those in the presence of vehicle. A similar enhancement of the ARNA responses to 10 pM NE by losartan+rauwolscine was observed in the experiments in which losartan or rauwolscine did not precede the losartan+rauwolscine perfusion (Group VII). In these rats, the ARNA responses to NE in the presence of vehicle and losartan+rauwolscine in the renal pelvis were 274 ± 137 and 1,859 ± 614%·s, respectively (P < 0.05 vs. vehicle, data not included in Fig. 3). MAP and HR were not affected by the renal pelvic administration of NE in any of the groups.

Fig. 3.

In vivo low-sodium diet: Effects of renal pelvic administration of vehicle (open bar) and losartan (hatched bar), rauwolscine (hatched bar), or losartan+rauwolscine (cross-hatched bar) on the ARNA responses to renal pelvic administration of 10 pM NE. Losartan or rauwolscine (random order) preceded the administration of rauwolscine+losartan. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. baseline, †P < 0.05, ‡P < 0.01, ARNA responses to NE during renal pelvic administration of rauwolscine+losartan vs. during vehicle administration. NE, norepinephrine.

In Vitro Studies

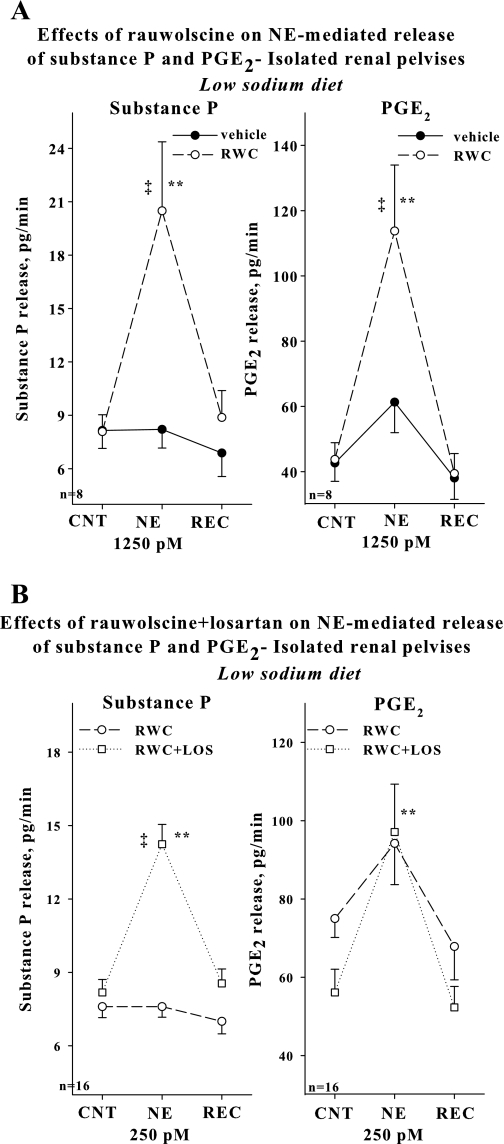

Groups VIII–XI, low-sodium diet: effects of an AT1 receptor antagonist and an α2-AR antagonist alone and in combination on the NE-induced increases in substance P and PGE2.

Our in vivo studies suggested an important inhibitory role for NE-mediated activation of α2-AR in the reduced activation of renal sensory nerves in rats fed a low-sodium diet in the presence of AT1 receptor blockade. To examine whether this mechanism involved presynaptic or postsynaptic activation of α2-AR, we used the isolated renal pelvic wall preparation. Our previous in vitro studies showed that the threshold concentration of NE for substance P release is 6,250 pM in rats fed a low-sodium diet and 250 pM in rats fed a normal-sodium diet (22, 24), suggesting that the reduced responsiveness of the renal sensory nerves to NE in rats fed a low-sodium diet involves mechanisms at the peripheral renal sensory nerve endings. Our initial studies showed that losartan failed to enhance renal pelvic release of substance P and PGE2 produced by NE at 6,250 and 1,250 pM (Table 2). In contrast, rauwolscine enhanced the increases in renal pelvic release of substance P produced by 6,250 pM NE, from 4.3 ± 0.5 to 9.8 ± 1.0 pg/min in the absence and from 6.2 ± 1.3 to 19.1 ± 2.8 pg/min (n = 4) in the presence of rauwolscine in the incubation bath. Further studies showed that rauwolscine also enhanced the increases in renal pelvic release of substance P and PGE2 produced by 1,250 pM NE (Fig. 4A). However, 250 pM NE failed to increase substance P and PGE2 in the presence of rauwolscine in the bath (Fig. 4B, Table 3). Adding both rauwolscine and losartan to the incubation bath normalized the responsiveness of the renal sensory nerves to NE. As shown in Fig. 4B and Table 4, 250 pM of NE resulted in significant increases in substance P and PGE2 in the presence of rauwolscine plus losartan in the bath.

Table 2.

Effects of losartan, 0.44 mM, on the norepinephrine-mediated release of substance P and PGE2 from isolated renal pelvic wall preparations derived from low-sodium diet rats

| Substance P, pg/min |

PGE2, pg/min |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 10 | Control | NE 6250 pM | Recovery | Control | NE 6250 pM | Recovery |

| Vehicle | 5.7 ± 0.7 | 8.9 ± 1.4** | 5.5 ± 0.6 | 33.5 ± 3.0 | 77.9 ± 11.5** | 38.0 ± 2.8 |

| Losartan | 5.2±.5 | 7.4 ± 0.9* | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 42.6 ± 4.3 | 77.2 ± 15.7** | 25.9 ± 3.3 |

| n = 6 | Control | NE 1250 pM | Recovery | Control | NE 1250 pM | Recovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vehicle | 5.3 ± 0.9 | 5.5 ± 1.2 | 5.5 ± 1.1 | 55.4 ± 5.1 | 77.7 ± 11.5 | 55.2 ± 3.4 |

| Losartan | 5.6 ± 1.3 | 6.8 ± 1.4 | 5.3 ± 1.2 | 63.6 ± 14.5 | 75.2 ± 12.7 | 45.0 ± 5.1 |

NE, norepinephrine.

P < 0.01,

P < 0.05 vs. average of control and recovery.

Fig. 4.

In vitro isolated renal pelvises, low-sodium diet. A: effects of 1,250 pM NE on the release of substance P and PGE2 in the presence of vehicle (solid line) or 0.1 μM rauwolscine (dashed line) in the bath. B: effects of 250 pM NE on the release of substance P and PGE2 in the presence of rauwolscine (dashed line) or rauwolscine+losartan (dotted line) in the bath.**P < 0.01, vs. CNT and REC; ‡P < 0.01 NE-induced substance P and PGE2 release in the presence of vehicle vs. rauwolscine (A) and rauwolscine vs. rauwolscine+losartan (B). CNT, control; REC, recovery.

Table 3.

Effects of norepinephrine, 250 pM, on the release of substance P and PGE2 from isolated renal pelvic wall preparations derived from low-sodium diet rats

| Substance P, pg/min |

PGE2, pg/min |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | NE, 250 pM | Recovery | Control | NE, 250 pM | Recovery | |

| Vehicle | 8.0 ± 1.2 | 8.5 ± 1.6 | 8.0 ± 1.4 | 59.6 ± 11.9 | 77.3 ± 12.3 | 50.0 ± 10.9 |

| Rauwolscine | 7.0 ± 1.0 | 9.4 ± 1.1 | 7.1 ± 1.0 | 66.9 ± 8.2 | 77.4 ± 8.0 | 63.4 ± 11.5 |

NE, norepinephrine.

Table 4.

Effects of losartan alone and in combination with rauwolscine on the norepinephrinemediated release of substance P and PGE2 from isolated renal pelvic wall preparations derived from low-sodium diet rats

| Substance P, pg/min |

PGE2, pg/min |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | NE 250 pM | Recovery | Control | NE 250 pM | Recovery | |

| LOS | 5.9 ± 0.7 | 6.0 ± 0.7 | 5.7 ± 0.6 | 67.7 ± 8.1 | 68.7 ± 14.8 | 41.7 ± 5.3 |

| LOS+RWC | 4.5 ± 0.6 | 10.1 ± 1.4**‡ | 4.5 ± 0.7 | 60.3 ± 10.2 | 103.7 ± 15.5** | 35.4 ± 5.9 |

NE, norepinephrine. LOS, losartan; RWC, rauwolscine.

P < 0.01 vs. average of control and recovery;

P < 0.01 vs. the NE-induced increase in substance P release during losartan alone.

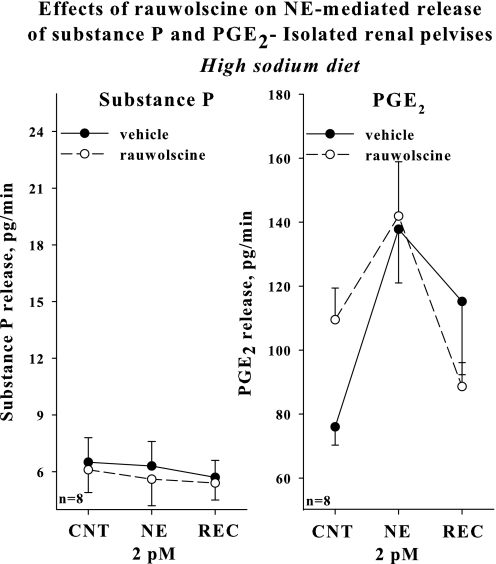

Group XII, high-sodium diet: effects of an α2-AR antagonist on the NE-induced increases in substance P and PGE2.

Adding rauwolscine to the incubation bath failed to enhance the increases in renal pelvic release of substance P and PGE2 produced by 2 pM NE, subthreshold concentration of NE for activation of renal sensory nerves in rats fed a high-sodium diet (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

In vitro isolated renal pelvises, high-sodium diet: effects of 2 pM NE on the release of substance P and PGE2 in the presence of vehicle (solid line) or 0.1 μM rauwolscine (dashed line) in the bath.

Immunohistochemistry

Localization of α2A- and α2C-AR in renal pelvis.

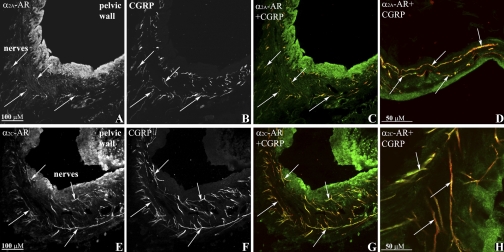

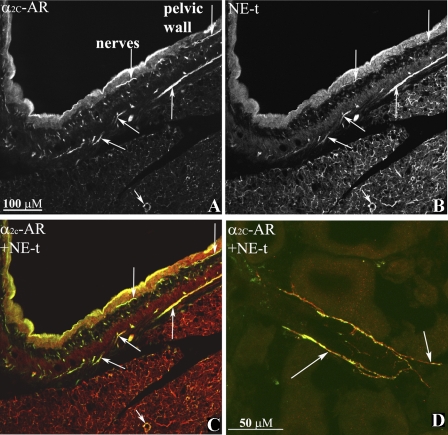

Renal tissues were double labeled with antibodies against α2A-AR, α2C-AR, and CGRP or NE-t. As shown in Fig. 6, A–C and E–G, the antibodies against α2A-AR and α2C-AR-labeled fibers that were on or close to CGRP-immunoreactive (ir) nerve fibers in the renal pelvic wall. Higher magnification suggested the presence of the α2-AR being located on the renal sensory nerve fibers (Fig. 6, D and H). The α2C-AR antibody also labeled fibers on or close to NE-t-ir nerve fibers in the pelvic wall (Fig. 7, A–C), renal fat tissue (not shown), and blood vessels (Fig. 7D). No such labeling was observed with the α2A-AR antibody.

Fig. 6.

Immunofluorescence double-labeling of renal tissue with antibodies against α2A-adrenoceptors (AR), α2C-AR (green) and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP; red) shows α2A-AR-immunoreactive (ir) fibers (A) and α2C-AR-ir fibers (E) close or on CGRP-ir sensory nerve fibers (B, C, and F, G, respectively) (colocalization yellow, arrows) in the renal pelvic wall. Higher magnification showed α2A-AR-ir (green, D) and α2C-AR-ir (green, H) on CGRP-ir fibers (red), colocalization yellow (arrows).

Fig. 7.

Immunofluorescence double-labeling of renal tissue with antibodies against α2C-AR (green) and NE-t (red) shows α2C-AR-ir fibers (A) close or on NE-t-ir fibers (B, C) (colocalization yellow, arrows) in the renal pelvic wall. Higher magnification showed α2C-AR-ir (green, D) on NE-t-ir fibers (red), colocalization yellow (arrows) on a vessel in renal cortical tissue.

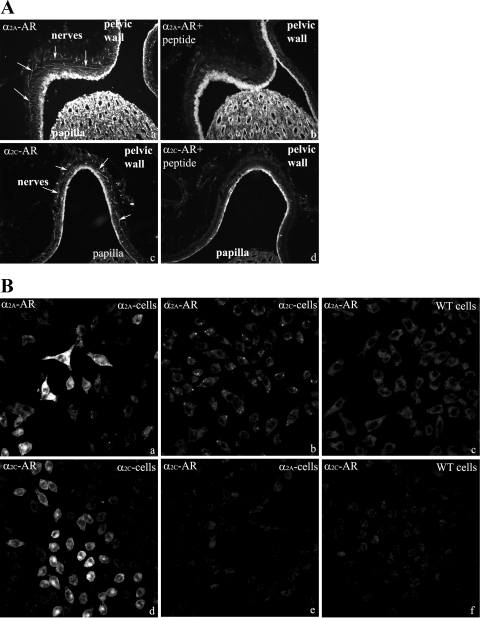

The α2A-AR and α2C-AR antibody labeling in the kidney was blocked by adsorption with the peptides used as immunogens for the generation of the α2A-AR and α2C-AR antibodies (Fig. 8A, a–d). α2A-AR-ir was only seen in CHO cells transfected to express α2A-AR (Fig. 8B, a–c). Likewise, α2C-AR-ir was only seen in CHO cells transfected to express α2C-AR (Fig. 8B, d–f). No labeling with either α2A-AR or α2C-AR antibodies was observed in nontransfected CHO cells.

Fig. 8.

A: immunofluorescence labeling of renal tissue shows α2A-AR-ir (a) and α2C-AR-ir (c) fibers in the renal pelvic wall (arrows). The α2A-AR and α2C-AR labeling is blocked by adsorption with the appropriate peptide (b and d). B: α2A-AR antibody labeled CHO cells transfected to express α2A-AR (a) but not cells transfected to express α2C-AR (b) or WT cells (c). The α2C-AR antibody labeled CHO cells transfected to express α2C-AR (d) but not cells transfected to express α2A-AR (e) or WT cells (f).

DISCUSSION

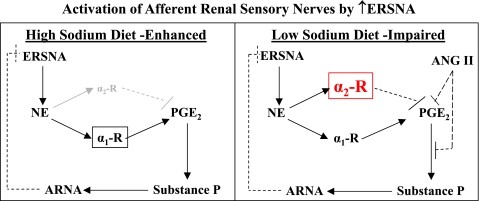

The interaction between ERSNA and ARNA is modulated by dietary sodium (24). The present results show that reduced activation of ARNA by reflex increases in ERSNA of rats fed a low-sodium diet is not affected by renal pelvic perfusion with losartan or rauwolscine alone but is enhanced by the combined administration of these two drugs. Likewise, losartan+rauwolscine, but not either agent alone, enhanced the ARNA responses to renal pelvic administration of NE. In vitro studies in isolated renal pelvic wall preparations from rats fed a low-sodium diet showed that rauwolscine but not losartan, alone, enhanced the release of substance P and PGE2 produced by 1,250 pM NE. At 250 pM, NE failed to increase substance P or PGE2 release in the presence of either losartan or rauwolscine alone but increased substance P and PGE2 significantly in the presence of both losartan and rauwolscine in the bath. In vivo and in vitro studies in rats fed a high-sodium diet showed that rauwolscine failed to enhance the responsiveness of the renal sensory nerves to reflex increases in ERSNA or NE. Immunohistochemical analysis suggested the presence of α2A-AR and α2C-AR on or close to the sensory nerves in the renal pelvic wall. Taken together, our studies support the notion that dietary sodium modulates the NE-mediated activation of α2-AR on renal pelvic sensory nerve endings, resulting in altered responsiveness of the renal sensory nerves to increases in ERSNA. Thus, in addition to endogenous ANG II inhibiting the responsiveness of the renal sensory nerves, increased activation of renal α2-AR appears to play an important inhibitory role in the interaction between ERSNA and ARNA in conditions of low sodium intake. Conversely, no or minimal activation of renal α2-AR facilitates the enhanced interaction between ERSNA and ARNA under high-sodium dietary conditions.

Interaction Between ERSNA and ARNA

Our previous studies in rats on a normal-sodium diet suggested that ERSNA increases ARNA by NE-mediated activation of α1-AR and decreases ARNA by NE-mediated activation of α2-AR (22).Our current functional studies showed that thermal cutaneous stimulation results in a general increase in sympathetic nerve activity, as evidenced by increases in MAP, HR, and ERSNA. The increases in these parameters were greater in the high- than in the low-sodium diet. The lack of statistically significant differences in the ERSNA responses to thermal cutaneous stimulation (P = 0.054) between rats fed high- and low-sodium diet in the current study is likely related to the magnitude of the ERSNA response being the result of both stimulatory reflexes (heating of the tail, per se) and inhibitory reflexes (activation of the renorenal and baroreceptor reflexes) (5). Nevertheless, the ERSNA-induced increases in ARNA differed in magnitude between the high- and low-sodium diet rats.

Mechanisms involved in the reduced responsiveness of renal sensory nerves in the low-sodium diet.

Activation of endothelin A (ETA) receptors contributes to the reduced ERSNA-ARNA interaction (24). However, the ETA-receptor antagonist did not normalize the responsiveness of the renal sensory nerves to NE in the low-sodium diet, suggesting that additional mechanisms contribute to the reduced ERSNA-ARNA interaction. Because increased ANG II levels in the renal pelvic wall (16) reduced the ARNA responses to increased renal pelvic pressure in rats on the low-sodium diet (16, 24), we reasoned that increased activation of AT1 receptors would contribute to the reduced interaction between ERSNA and ARNA. AT1 receptors are located on renal vascular and tubular structures (32, 50) and, most importantly, in the renal pelvic wall (8, 10, 31, 50). However, our initial studies showed no effects of renal pelvic administration of losartan on the increases in ARNA produced by reflex increases in ERSNA or on the substance P release produced by 1,250 or 6,250 pM NE, supramaximal concentrations of NE for substance P release in rats on a normal-sodium diet. The threshold concentration of NE for substance P release is 250 pM in rats fed a normal-sodium diet (22). These studies suggested that additional mechanisms were involved in suppressing the responsiveness of renal sensory nerves to changes in ERSNA and NE.

In view of our studies in rats fed a normal-sodium diet, which showed that rauwolscine enhanced the interaction between ERSNA and ARNA (22), we reasoned that among other possible inhibitory mechanisms that may contribute to the reduced ERSNA-ARNA interaction during low-sodium intake would be increased activation of renal pelvic α2-AR. The involvement of α2-AR in the central nervous system in cardiovascular regulation has long been known (35, 37), and activation of α2-AR on primary afferent neurons has antinociceptive effects (34). Three subtypes of α2-AR have been cloned, α2A, α2B, and α2C (2). There is widespread distribution of α2A-AR and α2C-AR in the central nervous system (33). NE is suggested to have higher affinity for α2C-AR, which is activated at lower action potential frequencies (11, 35). Both α2A-AR and α2C-AR are expressed on primary afferent neurons in the spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia (DRG) (42, 43). In the central nervous system, the available evidence indicates a limited distribution of α2B-AR (7, 11, 42, 43). Studies examining the presence of α2B-AR on DRG have shown conflicting results, with one study showing a majority of the neurons expressing α2B-AR (9), and other studies showing only a few neurons expressing α2B-AR (3, 42). Whereas many neurons in lumbar DRG showed coexpression of α2A-AR and α2C-AR mRNA with CGRP mRNA, only a very few neurons showed coexpression of α2B-AR with CGRP (42). In the kidney, the α2A-AR transcript is present in the outer and inner medulla, and the renal pelvic wall (30). A similar distribution, albeit somewhat with lower intensity, was observed for α2C-AR mRNA. The distribution of mRNA for α2B-AR is quite different, with intense expression in the renal cortex and outer medulla but no expression in the inner medulla or renal pelvic wall (30). There is limited immunohistochemical evidence for α2-AR on peripheral sensory nerve endings. A recent study by Riedl et al. (40) demonstrated colocalization of α2A-AR-ir and substance P-ir in skin sensory nerves.

The results of the present studies showed that in contrast to losartan, rauwolscine enhanced the responsiveness of the renal sensory nerves to relatively high concentrations of NE, 1,250 and 6,250 pM in vitro. These findings demonstrated important suppressive effects of α2-AR on renal sensory nerve activation in rats fed a low-sodium diet and suggested that activation of α2-AR by pharmacological concentrations of NE can suppress the responsiveness of the renal sensory nerves to physiological activation of AT1 receptors produced by a low-sodium diet. The lack of an effect of rauwolscine alone on the responsiveness of the renal sensory nerves to stimuli of a more physiological nature, e.g., thermal cutaneous stimulation in vivo and/or 250 pM NE in vitro in rats on a low-sodium diet, would support this hypothesis.

It is unlikely that the lack of effects of renal pelvic administration of rauwolscine on the activation of the renal sensory nerves in vivo and in vitro were due to rauwolscine not producing significant blockade of renal pelvic α2-AR. Rauwolscine was administered at a concentration, 0.1 μM, which is 25- and 500-fold higher than its Ki for α2A-AR and α2C-AR, respectively (2). Furthermore, the concentration of rauwolscine used in the current study is 10-fold higher than that shown to block renal vasoconstrictor responses to the α2-AR agonists clonidine and guanabenz (6). In addition, our previous studies showed that 0.1 μM rauwolscine enhances the activation of renal sensory nerves by increases in ERSNA in vivo and NE in vitro in rats fed a normal-sodium diet (22), a dietary condition characterized by low renal tissue levels of ANG II levels (12). Rather, we reasoned that suppression of the ARNA responses to sympathetic stimuli of a magnitude within the physiological range may involve increased activation of both α2-AR and AT1 receptors. If so, concurrent blockade of α2-AR and AT1 receptors would enhance the responsiveness of the renal sensory nerves to increases in ERSNA and NE. The results confirm our hypothesis. Renal pelvic administration of losartan+rauwolscine enhanced the ARNA responses to increases in ERSNA in vivo and lowered the responsiveness of the renal sensory nerves to NE for substance P release to 250 pM in vitro. The similar findings in vivo and in vitro suggested a mechanism(s) at the sensory nerve endings, the isolated renal pelvic wall preparation being sympathetically denervated.

The mechanisms by which losartan+rauwolscine enhanced the interaction between ERSNA and ARNA are currently unknown. Activation of the renal sensory nerves by increases in ERSNA and NE is dependent on intact PG synthesis (22). Our previous studies showed that increased activation of AT1 receptors reduced the ARNA response to increased renal pelvic pressure by inhibiting the PGE2-mediated activation of adenylyl cyclase by a PTX-sensitive mechanism (16). These findings, together with the α2-AR being coupled to PTX-sensitive Gi/o proteins (11, 48), suggest a similar mechanism being involved in the ANG II and NE-mediated suppression of the NE-mediated activation of renal sensory nerves in low-sodium dietary conditions. However, this reasoning does not explain the increases in NE-induced PGE2 release in the presence of rauwolscine and losartan. The increased PGE2 release may be related to cross-talk among the second messenger systems activated by Gq, Gi, and/or Gs protein-coupled receptors. Activation of Gi-coupled receptors has been shown to affect PLC and/or PKC activity either directly or via inhibition of the AC/cAMP transduction pathway in neuronal and nonneuronal cells (1, 28, 38, 47). The relevance of these findings to the current studies relates to our previous studies, showing that activation of renal mechanosensory nerves involves activation of the PKC and cAMP/PKA transduction cascades (16, 23). Whether the interaction between the activation of α2-AR and AT-1 receptors occurs at the level of the receptors or beyond is currently unknown.

Mechanisms involved in the enhanced responsiveness of renal sensory nerves under high-sodium dietary conditions.

A high-sodium diet enhances the responsiveness of the renal sensory nerves to NE, as evidenced by the greater ARNA responses to increases in ERSNA and the threshold concentration of NE for substance P release being 10 pM in high- vs. 6,250 pM in low-sodium dietary conditions (24). Our previous studies suggested an important role for ET-mediated activation of ETB receptors in the enhanced ARNA response to increases in ERSNA involving an interaction between α1-AR and ETB receptors (24). The present findings showed that rauwolscine has no effect on the ARNA responses to increases in ERSNA or the substance P release produced by 2 pM NE, a subthreshold concentration of NE for substance P release in rats on a high-sodium diet rats (24). It is unlikely that adding losartan to the renal pelvic perfusate containing rauwolscine would have resulted in increased responsiveness of the renal sensory nerves to increases in ERSNA and/or 2 pM NE in rats fed a high-sodium diet. Our previous studies showed that rats fed a high-sodium diet had markedly reduced endogenous ANG II concentrations in renal pelvic tissue compared with rats fed a low-sodium diet (16). It is highly likely that the responsiveness of the renal sensory nerves is modulated by renal pelvic tissue concentration and not urinary sodium concentration of ANG II because dietary sodium modulates the activation of the renal sensory nerves in a similar fashion in vivo and in vitro, the incubation bath being same for pelvises of rats on either a high or low-sodium diet. Furthermore, renal pelvic administration of losartan had no effect on the responsiveness of the renal sensory nerves to increases in renal pelvic pressure or PGE2 in rats fed a normal- or high-sodium diet (18). In view of the results from these previous studies, the findings from our current studies suggest that NE-mediated activation of α2-AR plays no or only a minimal role in the ERSNA-induced activation of the renal sensory nerves in rats on a high-sodium diet.

Taken together, our findings in rats fed a high-sodium or low-sodium diet suggest an important role for α2-AR in modulating the responsiveness of renal sensory nerves to increases in ERSNA during various dietary sodium intakes. The lack of effects of rauwolscine on the activation of the renal sensory nerves in rats fed a high-sodium diet is most likely not related to the low level of endogenous ANG II in renal pelvic tissue, since our previous studies showed that rauwolscine enhanced the responsiveness of the renal sensory nerves to similar stimuli in rats fed a normal-sodium diet (22), which is also characterized by low endogenous ANG II in renal tissue (12). Rather, the lack of effects of rauwolscine on the activation of the renal sensory nerves in rats fed a high-sodium diet is most likely related to the high-sodium diet, per se. Whether a high-sodium diet decreases the affinity of the α2-AR to NE and/or reduces the density of α2-AR on the renal sensory nerve fibers is currently unknown. Of interest in this context are studies in platelets and renal cortical tissue that showed decreased affinity of α2-AR with increasing Na+ concentrations (46, 49). The current studies showed no apparent differences in the intensity of labeling or number of nerve fibers in kidneys labeled with either antibody against the α2A-AR or α2C-AR between rats on high-sodium and low-sodium diets. It is well recognized that only large differences in antibody labeling can be detected by immunohistochemical analyses. Thus, these studies do not allow a firm conclusion about whether there is a difference in the labeling of the α2-AR antibodies of the renal sensory nerves among rats fed a high- or low-sodium diet.

Immunohistochemical analysis of α2-AR in renal pelvic tissue.

Because of the lack of truly subtype-selective agonists or antagonists of the α2-AR subtypes, the subtype involved in the modulation of the responsiveness of the peripheral renal sensory nerves to changes in ERSNA could not be evaluated in our functional studies. Previous in situ hybridization studies suggested the presence of α2A-AR and α2C-AR in renal pelvic tissue, without any evidence for α2B-AR (30). Therefore, our immunohistochemical studies focused on the localization of the α2A-AR and α2C-AR subtypes on or close to the peripheral sensory nerves in the renal pelvic wall. We applied the very same antibodies against α2A-AR and α2C-AR that have been previously and consistently shown to recognize the receptors against which they were generated (e.g., 7, 40, 45). Our studies showed that the α2A-AR antibody and α2C-AR antibody-labeled fibers in the renal pelvic wall that were also labeled with the CGRP antibody. These data suggested the presence of both α2A-AR and α2C-AR on renal sensory nerve fibers. Our studies further showed α2C-AR-ir fibers on or close to NE-t-ir fibers throughout the kidney, suggesting the presence of α2C-AR on renal sympathetic nerve fibers. It is unlikely that activation of these presynaptic receptors played a major role in the inhibition of the activation of renal sensory nerves due to the similar effects produced by rauwolscine in the innervated in vivo and denervated in vitro preparations.

Similar to previous studies in the spinal cord (7, 40, 45), the α2A-AR and α2C-AR labeling of the nerve fibers in renal tissue was blocked by preadsorption with the antigens used to generate the antibodies against the two α2-AR subtypes. Further studies using CHO cells transfected to express either α2A-AR or α2C-AR or neither, i.e., WT cells, showed a2A-AR-ir only on cells transfected to express α2A-AR, and α2C-AR-ir was observed only on cells transfected to express α2C-AR, in agreement with previous studies using Madin-Darby canine kidney cells (45). Taken together, these studies suggest that the α2A-AR-ir and α2C-AR-ir observed on/close to the renal sensory nerves in the pelvic wall represented the α2A-AR and α2C-AR subtypes, respectively. However, applying the antibodies against α2A-AR and α2C-AR to renal tissue derived from mice deficient in α2A-AR or α2A/2C-AR resulted in similar labeling as in WT mice (data not shown). The reasons for this apparent discrepancy in our studies examining the specificity of the two antibodies in labeling α2A-AR and α2C-AR are currently unclear. Although the α2A-AR and α2A/2C-AR-deficient mice lack functional α2A-AR and α2C-AR, we can currently not discount the possibility that there are remnants of the α2-AR proteins that are recognized by the two antibodies.

Perspectives and Significance

An important role for the renorenal reflex mechanism in determining ERSNA is suggested by our studies showing that increases in ERSNA increase ARNA (22, 24), which, in turn, would lead to decreases in ERSNA via activation of the renorenal reflexes, i.e., a negative feedback mechanism (26). Importantly, a high-sodium diet enhances the ERSNA-induced increases in ARNA (24), which would lead to increased inhibitory renorenal reflex control of ERSNA to minimize any ERSNA-induced sodium retention in high-sodium dietary conditions. Conversely, low-sodium diet reduces the ERSNA-induced increases in ARNA, which would lead to decreased inhibitory renorenal reflex control of ERSNA. Because increases in ERSNA are essential to prevent sodium loss in low-sodium dietary conditions (5), the reduced renorenal reflex control of ERSNA would serve as an important physiological mechanism that will contribute to the required increases in ERSNA to prevent sodium loss.

The current studies suggest that the altered responsiveness of the renal sensory nerves to increases in ERSNA produced by changes in dietary sodium involves modulation of the NE-mediated activation of α2-AR on the renal pelvic sensory nerves. For rats on a high-sodium diet, NE-mediated activation of the renal sensory nerves is mediated by activation α1-AR with little or no inhibitory effects produced by activation of α2-AR. For rats on a low-sodium diet, increased NE-mediated activation of α2-AR together with increased endogenous ANG II suppresses the NE-mediated activation of α1-AR (Fig. 9). Interestingly, α2-AR density in renal tissue is greater in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) than in Wistar-Kyoto rats (41) and increases further in conditions of high-sodium dietary intake in association with further increases in arterial pressure (41, 44). In this context, it is of interest that the responsiveness of the renal sensory nerves is impaired in SHR (14). In view of our current findings, we hypothesize that the impaired responsiveness of the renal mechanosensory nerves in SHR involves inappropriately increased activation of renal α2-AR, especially when rats are on a high-sodium diet. Thus, increased NE-mediated activation of α2-AR on the renal sensory nerves may play an important role in the development of salt-sensitive hypertension.

Fig. 9.

Graphs showing conclusion/hypothesis: Decreased activation of α2-AR contributes to enhanced NE-mediated activation of renal sensory nerves in high-sodium dietary conditions (left). In low-sodium dietary conditions, increased activation of α2-AR together with activation of AT1 receptors contribute to the reduced responsiveness of the renal sensory nerves to NE (right). Modulation of the interaction between ERSNA and ARNA is an appropriate physiological response to changes in dietary sodium intake in the overall goal of maintaining water and sodium balance.

GRANTS

This work was supported by grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs, The National Institutes of Health, Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, RO1 HL66068, Swedish Research Council (04X-2887), Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, Sweden, and the Academy of Finland.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for the generous supply of calcitonin gene-related peptide antiserum from the late Dr. J. H. Walsh and Dr. H. C. Wong, The Center for Ulcer Research and Education of the Veterans Affairs/University of California Gastroenteric Biology Center, Los Angeles (antibody/RIA Core Grant #DK41301). We also express our gratitude to Drs. M. Uhlén and J. Mulder, Science for Life Laboratory, Karolinska Institutet and The Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden, for generous donation of antiserum to the NE transporter.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bizzarri C, Di Girolamo M, D'Orazio MC, Corda D. Evidence that guanine nucleotide-binding protein linked to a muscarine receptor inhibits directly phospholipase C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87: 4889–4893, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bylund DB, Eikenberg DC, Hieble JP, Langer SZ, Lefkowitz RJ, Minneman KP, Molinoff PB, Ruffolo RJ, Trendelenburg U. International Union of Pharmacology nomenclature of adrenoceptors. Pharmacol Rev 46: 121–136, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cho HJ, Kim DS, Lee NH, Kim JK, Lee KM, Han KS, Kang YN, Kim KJ. Changes in the alpha 2-adrenergic receptor subtypes gene expression in rat dorsal root ganglion in an experimental model of neuropathic pain. Neuroreport 8: 3119−–3122., 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. DiBona GF, Jones SY, Sawin LL. Effect of endogenous angiotensin II on renal nerve activity and its arterial baroreflex regulation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 271: R361–R367, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. DiBona GF, Kopp UC. Neural control of renal function. Physiol Rev 77: 75–197, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. DiBona GF, Sawin LL. Role of alpha2-adrenergic receptor in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 9: 41–48, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fairbanks CA, Stone LS, Wilcox GL. Pharmacological profiles of alpha 2 adrenergic receptor agonists identified using genetically altered mice and isobolographic analysis. Pharmacol Ther 123: 224–238, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gasc JM, Shanmugam S, Sibony M, Corvol P. Tissue specific expression of type 1 angiotensin II receptor subtypes: an in situ hybridization study. Hypertension 24: 531–537, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gold MS, Dastmalchi S, Levine JD. Alpha 2 adrenergic receptor subtypes in rat dorsal root and superior cervical ganglion neurons. Pain 69: 179−–190., 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Healy DP, Ye MQ, Troyanovskaya M. Localization of angiotensin II type 1 receptor subtype mRNA in rat kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 268: F220–F226, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hein L. Adrenoceptors and signal transduction in neurons. Cell Tissue Res 326: 541–551, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ingert C, Grima ML, Coquard C, Barthelmebs M, Imbs JL. Effects of dietary salt changes on renal renin-angiotensin system in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 283: F995–F1002, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Koepke JP, Jones S, DiBona GF. Sodium responsiveness of central alpha2-adrenergic receptors in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 11: 326–333, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kopp UC, Cicha MZ. Impaired substance P release from renal sensory nerves in SHR involves a pertussis toxin sensitive mechanism. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 286: R326–R333, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kopp UC, Cicha MZ, Nakamura K, Nusing RM, Smith LA, Hökfelt T. Activation of EP4 receptors contributes to prostaglandin E2 mediated stimulation of renal sensory nerves. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 287: F1269–F1282, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kopp UC, Cicha MZ, Smith LA. Angiotensin blocks substance P release from renal sensory nerves by inhibiting PGE2-mediated activation of cAMP. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285: F472–F483, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kopp UC, Cicha MZ, Smith LA. Arterial pressure increases in afferent renal denervated rats on high sodium diet. Hypertension 42: 968–973, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kopp UC, Cicha MZ, Smith LA. Endogenous angiotensin modulates PGE2-mediated release of substance P from renal mechanosensory nerve fibers. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 282: R19–R30, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kopp UC, Cicha MZ, Smith LA. PGE2 increases release of substance P from renal sensory nerves by activating the cAMP-PKA transduction cascade. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 282: R1618–R1627, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kopp UC, Cicha MZ, Smith LA, Haeggström JZ, Samuelsson B, Hökfelt T. Cyclooxygenase-2 involved in stimulation of renal mechanosensitive neurons. Hypertension 35: 373–378, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kopp UC, Cicha MZ, Smith LA, Hökfelt T. Nitric oxide modulates the renal sensory nerve fibers by mechanisms related to substance P receptor activation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 281: R279–R290, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kopp UC, Cicha MZ, Smith LA, Mulder J, Hökfelt T. Renal sympathetic nerve activity modulates afferent renal nerve activity by PGE2-dependent activation of α1- and α2-adrenoceptors on renal sensory nerve fibers. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 293: R1561–R1572, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kopp UC, Farley DM, Cicha MZ, Smith LA. Activation of renal mechanosensitive neurons involves bradykinin, protein kinase C, PGE2 and substance P. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 278: R937–R946, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kopp UC, Grisk O, Cicha MZ, Smith LA, Steinbach A, Schlüter T, Mähler N, Hökfelt T. Dietary sodium modulates the interaction between efferent renal sympathetic nerve activity and afferent renal nerve activity: role of endothelin. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 297: R337–R351, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kopp UC, Jones SY, DiBona GF. Afferent renal denervation impairs baroreflex control of efferent renal sympathetic nerve activity. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R1882–R1890, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kopp UC, Olson LA, DiBona GF. Renorenal reflex responses to mechano-and chemoreceptor stimulation in the dog and rat. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 246: F67–F77, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kopp UC, Smith LA, DiBona GF. Facilitatory role of efferent renal nerve activity on renal sensory receptors. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 253: F767–F777, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Linn WW, Chen BC. Distinct PKC isoforms mediate the activation of cPLA2 and adenylyl cyclase by phorbol esters in RAW264.7 macrophages. Br J Pharmacol 125: 1601–1609, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Liu L, Barajas L. The rat renal nerves during development. Anat Embryol 188: 345–361, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Meister B, Dagerlind Å, Nicholas AP, Hökfelt T. Patterns of messenger RNA expression for adrenergic receptor subtypes in the rat kidney. J Pharm Exp Ther 268: 1605–1611, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Miyazaki Y, Tsuchida S, Nishimura H, Pope JC, Harris RC, McKanna JM, Inagami T, Hogan BLM, Fogo A, Ichikawa I. Angiotensin induces the urinary peristaltic machinery during the perinatal period. J Clin Invest 102: 1489–1497, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Navar G, Imig JD, Zou L, Wang CT. Intrarenal production of angiotensin II. Sem Nephrol 17: 412–422, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nicholas AP, Pieribone V, Dagerlind A, Meister B, Elde R, Hökfelt T. In situ hybridization. A complementary method to radioligand-mediated autoradiography for localizing adrenergic, alpha-2 receptor-producing cells. Ann NY Acad Sci 763: 222–242, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pertovaara A. Noradrenergic pain modulation. Progr Neurobiol 80: 53–83, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Philipp M, Brede M, Hein L. Physiological significance of α2-adrenergic receptor subtype diversity: one receptor is not enough. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 283: R287–R295, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pohjanoksa K, Jansson CC, Luomala K, Marjamäki A, Savola JM, Scheinin M. Alpha2-adrenoceptor regulation of adenylyl cyclase in CHO cells: dependence on receptor density, receptor subtype and current activity of adenylyl cyclase. Eur J Pharmacol 335: 53–63, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Punnen S, Urbanski R, Krieger AJ, Sapru HN. Ventrolateral medullary pressor area: site of hypotensive action of clonidine. Brain Res 422: 336–346, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rasolonjanahary R, Gerard C, Dufour MN, Homburger V, Enjalbert A, Guillon G. Evidence for a direct negative coupling between dopamine-D2 receptors and PLC by heterotrimeric Gi1/2 proteins in rat anterior pituitary cell membranes. Endocrinology 143: 747–754, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Reis DJ. Neurons and receptors in the rostroventrolateral medulla mediating the antihypertensive actions of drugs acting presynaptic alpha2-adrenoceptors in RVLM. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 27: S11–S18, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Riedl MS, Schnell SA, Overland AC, Chabot-Doré AJ, Taylor AM, Ribeiro-da-Silva A, Elde RP, Wilcox GL, Stone LS. Coexpression of α2A-adrenergic and δ-opioid receptors in substance P-containing terminals in rat dorsal horn. J Comp Neurol 513: 385–398, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sanchez A, Pettinger WA. Dietary sodium regulation of blood pressure and renal α1 and α2-receptors in WKY and SH rats. Life Sci 29:2795–2802, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shi TS, Winzer-Serhan U, Leslie F, Hökfelt T. Distribution and regulation of α2-adrenoceptors in rat dorsal root ganglia. Pain 84: 319–330, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shi TS, Winzer-Serhan U, Leslie F, Hökfelt T. Distribution of α2-adrenoceptor mRNAs in the rat lumbar spinal cord in normal and axotomized rats. NeuroReport 10: 2835–2839, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sripairojthikoon W, Wyss JM. High NaCl diets increase alpha2-adrenoceptors in renal cortex and medulla of NaCl-sensitive spontaneously hypertensive rats. Eur J Pharmacol 167: 355–365, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stone LS, Broberger C, Vulchanova L, Wilcox GL, Hökfelt T, Riedl MS, Elde RL. Differential distribution of α2A and α2C adrenergic receptor immunoreactivity in the rat spinal cord. J Neurosci 18: 5928–5937, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tsai BS, Lefkowitz RJ. Agonist-specific effects of monovalent and divalent cations on adenylate cyclase-coupled alpha adrenergic receptors in rabbit platelets. Mol Pharmacol 14: 540–548, 1978 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Vom Dorp F, Sari AY, Sanders H, Keiper M, Weernink PAO, Jakobs KH, Schmidt M. Inhibition of phospholipase C-epsilon by Gi-coupled receptors. Cell Signal 16: 921–928, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wettschureck N, Offermanns S. Mammalian G proteins and their cell type specific functions. Physiol Rev 85: 1159–1204, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Woodcock EA, Johnston CI. Characterization of adenylate cyclase-coupled alpha2-adrenergic receptors in rat renal cortex using [3H]yohimbine. Mol Pharmacol 22: 589–594, 1982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhuo JL. Renomedullary interstitial cells: a target for endocrine and paracrine actions of vasoactive peptides in the renal medulla. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 27: 465–473, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]