Abstract

Activation of pudendal afferents can evoke bladder contraction or relaxation dependent on the frequency of stimulation, but the mechanisms of reflex bladder excitation evoked by pudendal afferent stimulation are unknown. The objective of this study was to determine the contributions of sympathetic and parasympathetic mechanisms to bladder contractions evoked by stimulation of the dorsal nerve of the penis (DNP) in α-chloralose anesthetized adult male cats. Bladder contractions were evoked by DNP stimulation only above a bladder volume threshold equal to 73 ± 12% of the distension-evoked reflex contraction volume threshold. Bilateral hypogastric nerve transection (to eliminate sympathetic innervation of the bladder) or administration of propranolol (a β-adrenergic antagonist) decreased the stimulation-evoked and distension-evoked volume thresholds by −25% to −39%. Neither hypogastric nerve transection nor propranolol affected contraction magnitude, and robust bladder contractions were still evoked by stimulation at volume thresholds below the distension-evoked volume threshold. As well, inhibition of distention-evoked reflex bladder contractions by 10 Hz stimulation of the DNP was preserved following bilateral hypogastric nerve transection. Administration of phentolamine (an α-adrenergic antagonist) increased stimulation-evoked and distension-evoked volume thresholds by 18%, but again, robust contractions were still evoked by stimulation at volumes below the distension-evoked threshold. These results indicate that sympathetic mechanisms contribute to establishing the volume dependence of reflex contractions but are not critical to the excitatory pudendal to bladder reflex. A strong correlation between the magnitude of stimulation-evoked bladder contractions and bladder volume supports that convergence of pelvic afferents and pudendal afferents is responsible for bladder excitation evoked by pudendal afferents. Further, abolition of stimulation-evoked bladder contractions following administration of hexamethonium bromide confirmed that contractions were generated by pelvic efferent activation via the pelvic ganglion. These findings indicate that pudendal afferent stimulation evokes bladder contractions through convergence with pelvic afferents to increase pelvic efferent activity.

Keywords: cat, micturition, parasympathetic, sympathetic

depending on the stimulation frequency, electrical stimulation of pudendal afferents evokes spinal reflexes that either inhibit the bladder and promote continence or excite the bladder and cause micturition in both cats (5, 6, 41, 45, 49) and persons with spinal cord injury (48). Previous results suggest that bladder inhibition by pudendal afferent stimulation arises from activation of hypogastric efferents and subsequent synaptic and ganglionic inhibition of parasympathetic efferents (8, 30), but the mechanisms of bladder excitation by pudendal afferent stimulation are not known. Contraction of the bladder by pudendal afferent stimulation may result from activation of a vestigial reflex from perigenital afferents to the bladder (12) or activation of an augmenting reflex from urethral afferents to the bladder (3, 36). The objective of this study was to determine the contribution of sympathetic and parasympathetic mechanisms to the reflex activation of the bladder evoked by stimulation of pudendal afferents.

Previous data suggest that suppression of the tonic sympathetic inhibition of the bladder is responsible for reflex excitation of the bladder by pudendal afferent stimulation. Sympathetic efferent activity inhibits the bladder via α-adrenergic receptor-mediated inhibition at the vesical ganglia and β-adrenergic receptor-mediated direct inhibition of the detrusor muscle (13). The sympathetic (i.e., hypogastric) reflex response to pudendal afferent stimulation depends strongly on stimulation frequency. Low-frequency pudendal afferent stimulation evokes robust reflex activation of hypogastric efferents. However, as the frequency of pudendal afferent stimulation is increased, reflex activation of hypogastric efferents declines and stimulation suppresses ongoing intrinsic hypogastric activity (30). Similarly, the bladder response to pudendal afferent stimulation exhibits a parallel dependence on the stimulation frequency; stimulation at 5–10 Hz inhibits the bladder and promotes continence, while stimulation at 33–40 Hz excites the bladder and causes voiding (6, 42, 45). The correlation between the stimulation frequency tuning of pudendal afferent-evoked excitation of the bladder and pudendal afferent-evoked suppression of hypogastric efferents suggests that reduction of the tonic inhibitory sympathetic activity (i.e., inhibiting the inhibitor) is a potential mechanism underlying reflex bladder contraction evoked by pudendal afferent stimulation.

Alternatively, reflex bladder excitation evoked by pudendal afferent stimulation may be due to convergent reflex activation of parasympathetic bladder efferents (i.e., exciting the exciter). Pudendal afferent stimulation evokes bladder contraction only when the bladder volume is above a threshold volume (∼70–80% of the volume at which distension-evoked reflex bladder contractions occur) (4, 45), and this volume dependence is mediated by a neural rather than a biomechanical mechanism (4). Similarly, the magnitude of the pelvic efferent reflex response evoked by pudendal afferent stimulation increases with increased pelvic afferent activity (bladder pressure) (32). The similarity between the pelvic afferent (bladder pressure) dependence of pudendal afferent-evoked pelvic efferent activity and pudendal afferent-evoked bladder contractions suggests that convergence of somatic (pudendal) and parasympathetic (pelvic) afferents may underlie pudendal afferent-evoked activation of the bladder.

The results of the present study determine the contributions of sympathetic and parasympathetic mechanisms to bladder contractions evoked by stimulation of pudendal afferents in α-chloralose anesthetized male cats. While sympathetic activity contributed to determining the volume thresholds for stimulation-evoked and distension-evoked bladder contractions, pharmacological block or surgical interruption of the sympathetic innervation of the bladder did not influence the magnitude of the bladder contractions evoked by stimulation of pudendal afferents. Further, a strong correlation was observed between the magnitudes of pudendal afferent stimulation-evoked bladder contractions and bladder volume, indicating that convergence of pelvic afferents and pudendal afferents is responsible for bladder excitation evoked by pudendal afferents.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experiments were conducted on 10 sexually intact, male cats weighing 3.3–4.5 kg. All animal care and experimental procedures were approved by the Duke University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were in accord with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Research Council, 1996). Anesthesia was induced with ketamine HCl (35 mg/kg im) and maintained with α-chloralose (65 mg/kg iv supplemented at 15 mg/kg as needed). The end-tidal CO2 was maintained between 3.0 and 4.0% with artificial respiration, core body temperature was maintained at ∼38°C with a thermostatic heating pad, and blood pressure was monitored through a catheter in the carotid artery. Intravenous fluids (lactated Ringer's solution or saline/5% dextrose/sodium bicarbonate solution) were administered at 15 ml·kg−1·h−1 through the cephalic vein. The bladder was accessed through a midline abdominal incision. In seven cats, a 3.5 French catheter was inserted into the bladder dome and secured with a purse-string suture, and the catheter was then connected to a solid-state pressure transducer (Deltran, Utah Medical) to record the bladder pressure. The catheter was also connected to a syringe for infusion of room temperature saline into the bladder. The abdominal incision was closed in layers. In all cats, a 3.5 or 5 French catheter was inserted into the urethra via the urethral meatus to occlude the urethra and prevent bladder voiding. The urethral catheter was connected to a syringe and used for instilling saline into the bladder in the three cats without suprapubic catheters. Whether filling was performed through the suprapubic or urethral catheter did not appear to impact the results.

In one cat, the spinal cord was transected at the T10 vertebral level. The cord was exposed via laminectomy, the dura was incised, and lidocaine was administered to the exposed cord. The spinal cord was elevated and transected, and Surgicel was packed between the transected ends of the spinal cord.

Nerve access and stimulation.

An incision was made from the skin around the prepuce to the caudal border of the gracilis muscle. The DNP was dissected free (unilaterally) from the body of the penis at the proximal end of the penile body, just distal to the bulb of the penis. A monopolar cuff electrode consisting of a platinum contact embedded in a silicone elastomer cuff was placed around the nerve, and a subcutaneous needle was inserted in the ipsilateral leg for the return electrode. Stimulation consisted of trains of constant-current (50–750 μA) 100-μs stimulation pulses.

The hypogastric nerves were accessed via a midline abdominal incision and, where indicated, were transected distal to the inferior mesenteric ganglia. Control filling trials were conducted in advance of hypogastric nerve transection but after surgical exposure of the nerve to prevent colon manipulation during nerve exposure from affecting the comparison of control and nerve transection trials. Hypogastric nerve transection was conducted in five cats: one before any other treatment, two after prior administration and washout of phentolamine and propranolol (see Drug administration), one after prior administration and washout of propranolol only, and one after prior administration and washout of phentolamine only. As well, in four of these cats, both phentolamine and propranolol were administered after bilateral hypogastric nerve transection, and these data were treated separately from the analysis of the effects of phentolamine and propranolol in isolation.

Drug administration.

Drugs were administered intravenously via a catheter in the cephalic vein. Propranolol HCl (Bedford Laboratories), a β-adrenergic antagonist, and phentolamine HCl (Sigma-Aldrich), an α-adrenergic antagonist, were administered at 1 mg/kg and 2 mg/kg, respectively (10, 16, 17, 28, 37). Heart rate and arterial blood pressure were monitored to establish the onset of drug effects. As well, the adrenergic agonists phenylephrine HCl (α-agonist; Parenta Pharmaceuticals) and isoproterenol HCl (β-agonist, Sigma-Aldrich) were administered intravenously (at 30 and 50 μg/kg, respectively) before and after administration of phentolamine and propranolol, respectively, to confirm the effects of the antagonists. Hexamethonium bromide (Sigma-Aldrich) was administered intravenously at 1 mg/kg in three cats to investigate the effect of ganglionic block on the bladder contractions evoked by DNP stimulation.

Phentolamine was administered in six cats: in four cats before any other treatment; administered a second time after washout in two cats; and in two cats after administration and washout of propranolol. Propranolol was administered in six cats: in four cats before any other treatment; administered a second time after washout in two cats; and in two cats after administration and washout of phentolamine.

Determining volume thresholds.

Intermittent electrical stimulation of the DNP during bladder filling was used to determine the volume thresholds for stimulation-evoked bladder contractions and distension-evoked reflex bladder contractions. Starting with an empty bladder, the bladder volume was increased by infusion of a 1-ml bolus of room temperature saline every 1 min through the urethral or suprapubic catheter. Stimulation at 33 Hz for 20 s was applied 20 s after injecting each bolus. Stimulation intensity was fixed at two times the threshold to evoke a reflex EMG response in the external anal sphincter. Trials were ended several boluses after the appearance of robust distension-evoked reflex contractions. At least 15 min, with the bladder empty, elapsed between consecutive filling trials, and a minimum of two control bladder filling trials preceded drug administration. Experimental trials were initiated 15–20 min following drug administration and were not continued beyond 90 min following drug administration. At least 2 h elapsed following drug administration before establishing new controls for subsequent drug administration or nerve transection. Threshold volumes for stimulation-evoked and distention-evoked bladder contractions (the primary outcome variables to assess the effects of adrenergic receptor blockade and hypogastric nerve transection) were remarkably stable during the course of the experiment. Across four animals in which control volumes were reestablished repeatedly between administration of propranolol and phentolamine, stimulation-evoked volume thresholds varied by only 0–3 ml (mean = 1 ml) and distention-evoked volume thresholds varied by 0–13 ml (mean = 4.75 ml). Stimulation-evoked inhibition of distention-evoked reflex bladder contractions was investigated at the end of filling trials in four animals by stimulating during contractions at 10 Hz with an amplitude equal to three times the threshold to evoke a reflex EMG response in the external anal sphincter.

Data analysis.

The bladder response to electrical stimulation was analyzed by comparing the bladder pressure before and during DNP stimulation. The average bladder pressure during the 3 s prior to stimulation onset was defined as the baseline pressure, and a stimulation-evoked contraction was determined to have occurred if the bladder pressure increased by > 10 cmH2O during the first 8 s of stimulation and was maintained until the end of stimulation. Distension-evoked reflex contractions were defined as transient rises in bladder pressure (> 10 cmH2O compared with the prebolus bladder pressure) occurring between 5 and 20 s after injecting a 1-ml bolus. Threshold pressures for both distention-evoked and stimulation-evoked bladder contractions were determined by averaging the pressure over three seconds before bolus injection or stimulation delivery at the respective threshold volumes. Bladder inhibition was defined as a > 10 cmH2O decrease in bladder pressure within the first 8 s of stimulation. The mean and maximum bladder contraction magnitudes were determined for the contraction evoked by stimulation at volumes 1 ml less than the distension-evoked contraction volume threshold. Mean stimulation-evoked contraction magnitudes were determined by averaging the bladder pressure from the onset of contraction (>10 cmH2O increase in pressure) until the termination of stimulation. The maximum contraction magnitude was defined as the maximum bladder pressure during stimulation. Distension-evoked contraction magnitudes were quantified for the contractions occurring at volumes 2 ml above the distension-evoked threshold volume by calculating the average bladder pressure for the 15 s prior to the onset of DNP stimulation.

Experimental trials were grouped with the control trials that preceded those experimental trials, and the volume thresholds were normalized by dividing the threshold volumes by the average of the control distension-evoked threshold volumes. The normalized values were averaged for each cat and compared for statistically significant differences using ANOVA with post hoc paired comparisons using Bonferroni correction. Contraction magnitudes (mean and maximum) were normalized for each set of control and experimental trials by dividing each magnitude by the average of the control magnitudes. Normalized contraction magnitudes were compared using an unpaired, two-tailed t-test. Bladder inhibition was quantified by taking the ratio of the average bladder pressure for the final 10 s of 10 Hz DNP stimulation and the average pressure for 3 s prior to the onset of the distension-evoked contraction. Ratios before and after sympathetic block were compared using a paired, two-tailed t-test. All reported values are means ± SD.

RESULTS

Volume thresholds for distension-evoked and stimulation-evoked contractions.

High-frequency (33 Hz) stimulation of pudendal afferents in the DNP evoked bladder contractions in 10 of 10 cats. In nine cats, the bladder volume thresholds for distension-evoked reflex contractions [distention-evoked threshold volume (DTV)] and the bladder volume thresholds for stimulation-evoked contractions [stimulation-evoked threshold volume (STV)] were determined during bladder filling in 1-ml increments (Fig. 1A). Stimulation-evoked bladder contractions during control filling (in the absence of sympathetic block) were evoked at STVs (mean: 18 ± 9 ml, range: 5–33 ml, n = 9 cats) that were 74 ± 11% of the DTVs (mean ± SD: 24 ± 12, range: 8–42 ml). Similarly, threshold pressures were lower for stimulation-evoked bladder contractions (16 ± 3 cmH2O) than threshold pressures for distention-evoked bladder contractions (18 ± 4 cmH2O, P < 0.001). Mean (29 ± 10 cmH2O, n = 9 cats) and maximum (55 ± 15 cmH2O) stimulation-evoked contraction magnitudes were determined at bladder volumes 1 ml less than DTV, and mean (10 ± 5 cmH2O) and maximum (40 ± 28 cmH2O) distension-evoked bladder contraction magnitudes were determined at bladder volumes 2 ml greater than DTV.

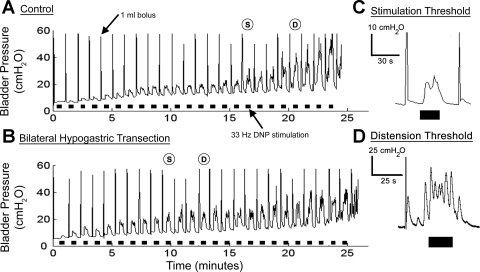

Fig. 1.

Volume thresholds for stimulation-evoked and distension-evoked reflex bladder contractions were determined under control and sympathetic block conditions. A: control filling trial consisting of a 1-ml bolus of saline injected into the bladder every minute with 20 s of 33 Hz stimulation of pudendal afferents in the dorsal nerve of the penis (DNP) delivered between boluses. The stimulation-evoked contraction volume threshold (S) was 17 ml and the distension-evoked threshold (D) was 21 ml. B: a filling trial after bilateral hypogastric nerve transection. The stimulation-evoked contraction volume thresholds decreased to 10 ml and the distension-evoked threshold decreased to 13 ml. C: an example bladder pressure trace at the stimulation-evoked volume threshold. D: an example bladder pressure trace at the distension-evoked volume threshold. A–D: black bars under the pressure trace indicate DNP stimulation at 33 Hz and 2× the intensity threshold for evoking a reflex response in the external anal sphincter.

Blockade of β-adrenergic receptors decreased volume thresholds.

Bladder filling and stimulation were repeated following administration of the β-adrenergic antagonist propranolol (1 mg/kg) in six cats. Bladder contractions were still evoked by DNP stimulation and distension following propranolol administration (Fig. 2A), but volume thresholds were significantly reduced (Fig. 2B). After propranolol administration, stimulation-evoked bladder contractions were evoked at lower volumes (STV: 11 ± 7 ml, range: 4–21 ml, n = 6 cats) than under control conditions (STV: 18 ± 11 ml, range: 5–27 ml), and propranolol similarly decreased threshold volumes for distension-evoked contractions (DTV: 18 ± 12 ml, range: 7–39 ml) compared with control (DTV: 24 ± 15 ml, range: 8–43 ml). Thus, after propranolol administration, bladder contractions were still evoked by stimulation at volumes less than the threshold for distension-evoked reflex contractions (63 ± 19% of DTV, compared with 70 ± 11% under control conditions). Stimulation-evoked contraction magnitudes after propranolol (mean: 32 ± 9 cmH2O, maximum: 63 ± 10 cmH2O) were similar to those evoked in control conditions (mean: 30 ± 9 cmH2O, maximum: 57 ± 14 cmH2O) (Fig. 2C). Similarly, distension-evoked contraction magnitudes were not affected by propranolol administration (Fig. 2C). As well, propranolol administration did not influence threshold pressures for distention-evoked (20 ± 3 cmH2O, P = 0.35) or stimulation-evoked (16 ± 4 cmH2O, P = 0.16) contractions. Propranolol administration blocked the transient increase in heart rate evoked by the β-adrenergic agonist isoproterenol (50 μg/kg iv; 41 ± 7 beats/min increase in the absence of propranolol vs. 1.5 ± 0 beats/min in the presence of propranolol), confirming the effectiveness of the drug and dose (n = 3 cats).

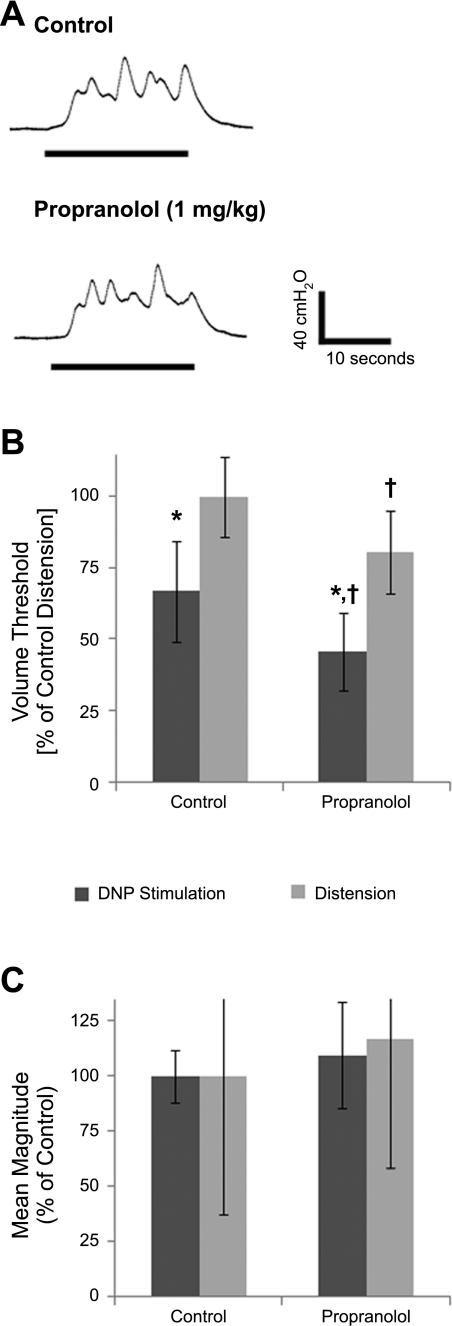

Fig. 2.

Effect of propranolol administration on bladder contractions evoked by DNP stimulation or distension. A: example bladder responses evoked by 33 Hz DNP stimulation before and after propranolol administration (1 mg/kg). The contractions were evoked during bladder filling trials at bladder volumes 1 ml less than the distension-evoked threshold volume. B: normalized volume thresholds before and after propranolol administration were significantly different. (P < 10−4, ANOVA, n = 6 cats). *Significant difference between stimulation-evoked and distension-evoked volume thresholds for control trials or for propranolol trials (P < 0.05, post hoc Bonferroni comparisons). †Significant difference between control and propranolol stimulation volume thresholds or for distension volume thresholds (P < 0.05, post hoc Bonferroni comparisons). C: normalized mean contraction magnitudes evoked by stimulation before and after propranolol were not different (P = 0.15, t-test, n = 6 cats). Also, distension-evoked contraction magnitudes increased slightly following propranolol, but the difference compared with control distension-evoked contractions was not significant (P = 0.28).

Blockade of α-adrenergic receptors increased volume thresholds and decreased contraction magnitudes.

Following administration of the α-antagonist phentolamine (2 mg/kg), bladder contractions were still evoked by DNP stimulation and distension in six of six cats (Fig. 3A), but volume thresholds were significantly increased (Fig. 3B). After phentolamine, STVs (mean: 26 ± 5 ml, range: 18–31 ml, n = 6 cats) and DTVs (mean: 33 ± 8 ml, range: 21–44 ml) were both increased compared with controls (STVs: 22 ± 5 ml, range: 15–28 ml; DTVs: 28 ± 8 ml, range: 17–37 ml), and stimulation still evoked bladder contractions at volumes below the DTV (STVs were 81 ± 8% of DTVs after phentolamine compared with 79 ± 13% under control conditions). However, stimulation-evoked contraction magnitudes were smaller after phentolamine (mean: 21 ± 9 cmH2O, maximum: 41 ± 16 cmH2O) compared with control contraction magnitudes (mean: 28 ± 11 cmH2O, maximum: 53 ± 16 cmH2O) (Fig. 3C). The distension-evoked contraction magnitudes following phentolamine were also smaller than under control conditions, but the difference was not significant (Fig. 3C). Phentolamine administration did not influence threshold pressures for distention-evoked contractions (20 ± 6 cmH2O, P = 0.20) but did cause a small increase in threshold pressures for stimulation-evoked contractions (18 ± 3 cmH2O, P = 0.02). Phentolamine administration blocked the transient increase in arterial pressure caused by administration of the α-agonist phenylephrine (30 μg/kg iv; 64 ± 8 mmHg increase in the absence of phentolamine vs. 2 ± 1 mmHg increase in the presence of phentolamine, n = 3 cats), verifying the effectiveness of the dose.

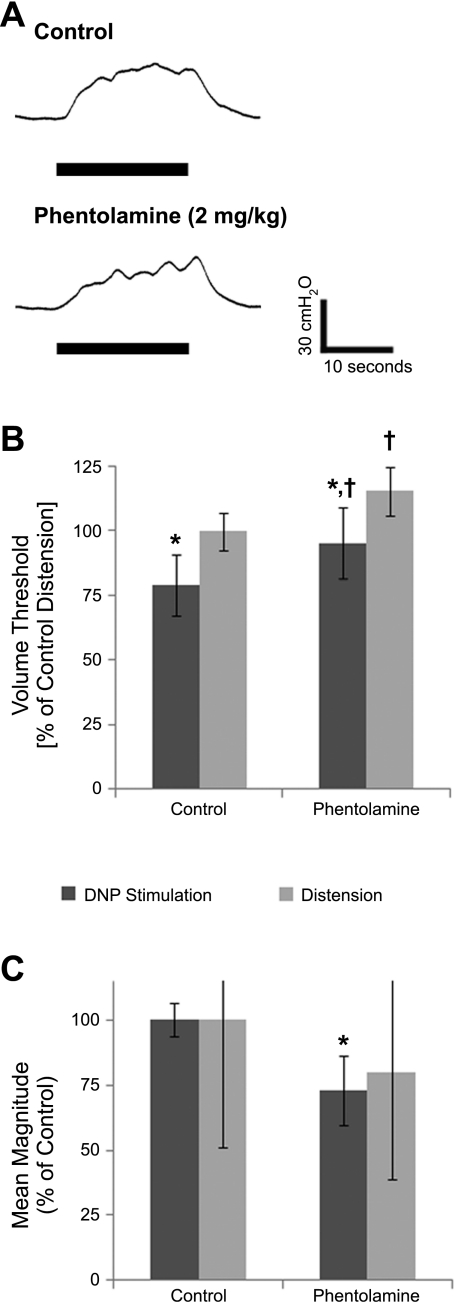

Fig. 3.

Effect of phentolamine administration on bladder contractions evoked by DNP stimulation or distension. A: contractions evoked at bladder volumes 1 ml less than the distension-evoked threshold volumes by 33 Hz DNP stimulation before and after phentolamine (2 mg/kg). B: normalized stimulation-evoked and distension-evoked reflex bladder contraction volume thresholds before and after phentolamine were significantly different (P < 10−5, ANOVA, n = 6 cats). *Significant difference between stimulation-evoked and distension-evoked volume thresholds for control trials or for phentolamine trials (P < 0.05, post hoc Bonferroni comparisons). †Significant difference between control and phentolamine stimulation volume thresholds or for distension volume thresholds (P < 0.05, post hoc Bonferroni comparisons). C: normalized mean contraction magnitudes evoked by 33 Hz DNP stimulation before and after phentolamine (*P < 0.02, t-test, n = 6 cats). Distension-evoked contractions decreased after phentolamine, but the difference in relative contraction magnitudes was not significant (P = 0.34).

Hypogastric nerve transection decreased volume thresholds.

Bladder contractions were still evoked by DNP stimulation and distension following bilateral transection of the hypogastric nerve in five of five cats (Fig. 4A), but threshold volumes were decreased (Figs. 1B and 4B). Hypogastric nerve transection caused a decrease in STVs (control: 16 ± 11 ml, n = 5 cats; transection: 11 ± 9 ml) and DTVs (control: 22 ± 13 ml; transection: 16 ± 11 ml), but STVs remained lower (72 ± 16%) than DTVs after hypogastric transection, comparable to the relative volume thresholds under control conditions (75 ± 10%). Bilateral hypogastric transection did not cause significant changes in the mean (30 ± 14 cmH2O) or maximum (59 ± 23 cmH2O) magnitude of stimulation-evoked bladder contractions compared with control contraction magnitudes (mean: 31 ± 13 cmH2O, maximum: 59 ± 21 cmH2O) (Fig. 4C) or in the threshold pressures for distention-evoked (17 ± 6 cmH2O, P = 0.43) or stimulation-evoked (14 ± 5 cmH2O, P = 0.08) contractions. The bladder volume thresholds and stimulation-evoked contraction magnitudes following hypogastric transection were not affected by subsequent administration of both propranolol and phentolamine (four cats) (Fig. 4, B and C). Distension-evoked contraction magnitudes were also not affected by hypogastric nerve transection or subsequent drug administration (Fig. 4C).

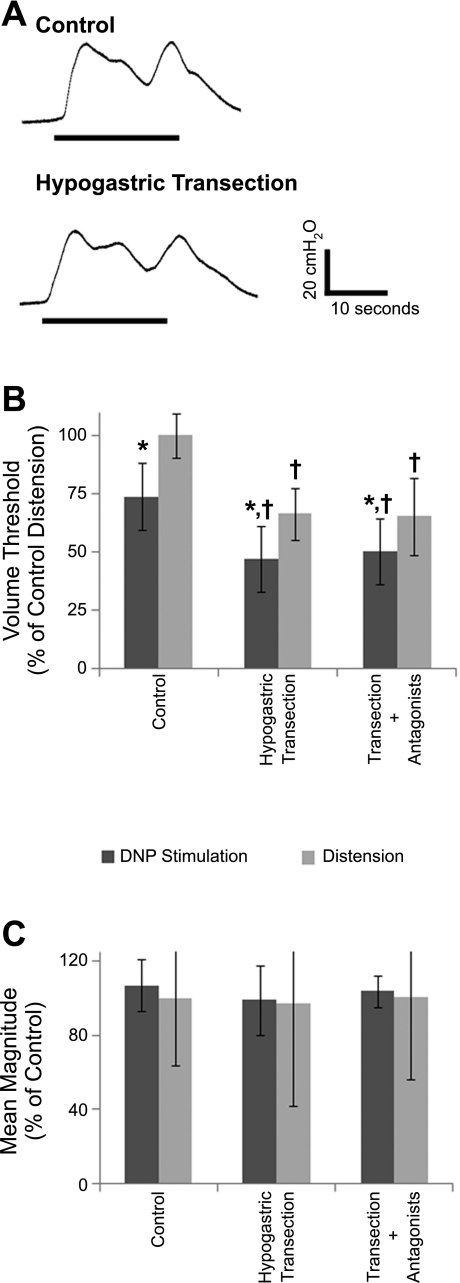

Fig. 4.

Effect of bilateral hypogastric nerve transection and subsequent adrenergic antagonist administration on bladder contractions evoked by DNP stimulation or distension. A: contractions evoked by 33 Hz DNP stimulation at a volume 1 cc less than the distension-evoked threshold volumes before and after bilateral hypogastric nerve transection. B: normalized volume thresholds before and after hypogastric nerve transection and after subsequent propranolol and phentolamine administration. Volume thresholds were significantly different (P < 10−12, ANOVA, n = 36 trials). *Stimulation-evoked volume thresholds were significantly less than distension-evoked thresholds for the treatment group (P < 0.05, post hoc Bonferroni comparisons). †Significant difference between treatment and control volume thresholds for stimulation thresholds or for distension thresholds (P < 0.05, post hoc Bonferroni comparisons). C: normalized mean contraction amplitudes evoked by DNP stimulation before and after hypogastric nerve transection and subsequent drug administration were not significantly different (P = 0.35, t-test, n = 36 contractions). Normalized distension-evoked contraction magnitudes also were not significantly altered by hypogastric nerve transection or subsequent drug administration (P = 0.96).

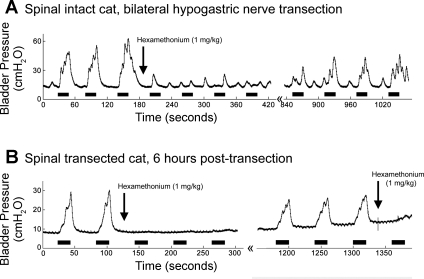

Hexamethonium bromide abolished stimulation-evoked contractions.

In two of two cats, administration of hexamethonium bromide (1 mg/kg) following bilateral hypogastric nerve transection abolished the bladder contractions evoked by DNP stimulation (Fig. 5). The bladder contractions evoked by stimulation returned over time as the ganglionic block diminished. In one cat, the spinal cord was transected at T10 and bladder contractions were evoked by DNP stimulation 6 h following spinal cord transection. Administration of hexamethonium bromide abolished the bladder contractions evoked by stimulation following spinal cord transection.

Fig. 5.

Hexamethonium bromide abolished the bladder contractions evoked by DNP stimulation. DNP stimulation [black bars, 33 Hz at (A) 300 μA or (B) 200 μA] evoked bladder contractions following (A) hypogastric nerve transection and (B) 6 h after acute spinal cord transection at the T10 vertebral level, but administration of hexamethonium bromide (1 mg/kg) abolished the stimulation-evoked contractions. The stimulation-evoked bladder contractions returned ∼14 min (A) and 20 min (B) later.

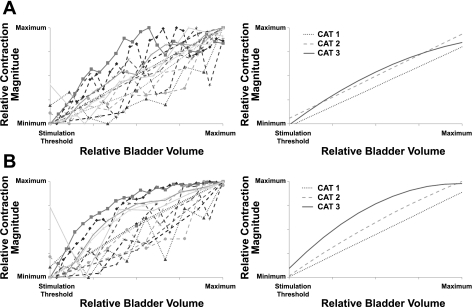

Stimulation-evoked contraction magnitudes increased with increasing bladder volume.

In three cats, the mean and maximum contraction magnitudes evoked by DNP stimulation across a range of bladder volumes were used to determine the relationship between bladder volume and contraction magnitude (Fig. 6). Regression analysis revealed a strong, positive correlation between the mean or maximum contraction magnitude and the bladder volume, and this strong, positive correlation persisted following bilateral hypogastric nerve transection.

Fig. 6.

The magnitude of bladder contractions evoked by DNP stimulation were strongly correlated with bladder volume before (A) and after (B) bilateral hypogastric nerve transection. The magnitudes of DNP stimulation-evoked bladder contractions were determined at 1-cc volume intervals between the stimulation-evoked contraction volume threshold and suprathreshold volumes. Contraction magnitudes were normalized by scaling between 0 (minimum value) and 1 (maximum value). A, left: normalized mean contraction pressures as a function of normalized bladder volume; right: regression lines (linear or quadratic) for the relationship between bladder volume and mean contraction magnitude for each cat. A significant correlation was found between mean contraction magnitude and bladder volume for all 3 cats investigated (P < 0.0001, Cat 1: r = 0.8518, n = 3; Cat 2: r = 0.8480, n = 7; Cat 3: r = 0.8708, n = 4). B: after bilateral hypogastric nerve transection. Left: normalized maximum contraction magnitudes as a function of normalized bladder volume. Right: regression lines (linear or quadratic) for the relationship between bladder volume and maximum contraction magnitude for each cat. A significant correlation was found between maximum contraction magnitude and bladder volume for all 3 cats investigated (P < 0.0001, Cat 1: r = 0.8893, n = 3; Cat 2: r = 0.8687, n = 7; Cat 3: r = 0.8688, n = 4).

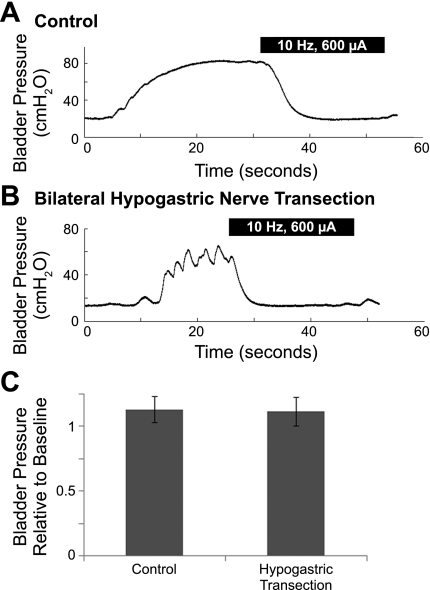

Bladder inhibition persisted following bilateral hypogastric nerve transection.

Stimulation of the DNP at 10 Hz inhibited distension-evoked reflex bladder contractions in four of four cats. Following hypogastric transection (4 cats) and hypogastric transection plus administration of phentolamine and propranolol (3 cats), 10 Hz DNP stimulation continued to evoke robust bladder inhibition (Fig. 7A). The reductions in bladder pressure (relative to baseline) evoked by 10 Hz stimulation following bilateral hypogastric nerve transection were identical to the reductions evoked under control conditions (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Inhibition of distension-evoked reflex bladder contractions by 10 Hz DNP stimulation before and after bilateral hypogastric nerve transection. A: bladder inhibition evoked by 10 Hz DNP stimulation under control conditions. B: after hypogastric transection, 10 Hz DNP stimulation still evoked bladder inhibition. A–B: black bars indicate DNP stimulation. C: bladder pressures during the last 10 s of 10 Hz DNP stimulation were compared with the baseline bladder pressure before the distension-evoked contractions. Bladder pressure relative to baseline was not significantly different for DNP stimulation-evoked inhibition before and after hypogastric nerve transection (P = 0.74, 2-tailed, unpaired t-test, n = 20 trials across 3 cats).

DISCUSSION

The mechanisms of reflex bladder excitation by activation of pudendal afferents were investigated using a combination of selective pharmacological sympathetic block and sympathetic block via hypogastric nerve transection. The sympathetic bladder innervation did not play a significant role in the reflex activation of the bladder evoked by pudendal afferent stimulation, but did play a pivotal role in determining the threshold volumes for stimulation-evoked and distention-evoked reflex bladder contractions. These results indicate that suppression of sympathetic efferent activity in the hypogastric nerve by pudendal nerve stimulation (i.e., inhibiting the inhibitor) is not the mechanism for bladder contractions evoked by pudendal afferent stimulation, but rather imply that convergence of pelvic and pudendal afferents (driving pelvic efferent activity) is responsible for bladder excitation evoked by pudendal afferents. This alternative hypothesis was supported by the lower volume threshold for stimulation-evoked bladder contractions compared with distension-evoked bladder contractions and the strong positive correlation between bladder volume (i.e., increased pelvic afferent activity) and the magnitude of stimulation-evoked bladder contractions. Further, the abolition of stimulation-evoked bladder contractions following administration of hexamethonium bromide confirmed that contractions were generated by pelvic efferent activation in the pelvic ganglion and not through an alternative pathway (e.g., somatic muscle contraction). These findings indicate that pudendal afferent stimulation evokes bladder contractions through convergence with pelvic afferents to increase pelvic efferent activity (i.e., exciting the exciter).

Selective pharmacological block of sympathetic activity revealed the importance of the sympathetic bladder innervation in determining the volume thresholds for distention-evoked and stimulation-evoked contractions. While complete block of adrenergic bladder innervation with chemical antagonists cannot be guaranteed, phentolamine and propranolol were administered at doses previously found to have maximal effects on bladder and urethral function (10, 16, 17, 28, 37). Additionally, although adrenergic agonists were administered to confirm antagonist effectiveness, secondary effects of the drugs may have altered the bladder activity. For example, adrenergic antagonists block sympathetic inhibition of the colon in the cat (19), and changes in intracolonic pressure can modulate bladder parasympathetic activity (32). As well, increases in β-adrenergic tone triggered by reductions in blood pressure following α-adrenergic blockade with phentolamine may have contributed to the observed increases in bladder volume thresholds. For example, hypogastric nerve activity augments bladder inhibition generated by pudendal afferent stimulation (42), while, as shown here, blocking the β-component decreases bladder volume thresholds. Importantly, this secondary effect does not influence the conclusion that α- or β-receptor-mediated sympathetic components are not critical to DNP stimulation-evoked bladder contractions.

β-adrenergic block.

Pharmacological block of the sympathetic pathways innervating the urinary bladder illustrated the importance of the β-adrenergic receptors in determining the volume thresholds for distention-evoked and stimulation-evoked contractions. Blocking the β-adrenergic bladder pathway with propranolol reduced volume thresholds but did not affect the magnitude of the electrically evoked bladder contraction. The reduction in distension-evoked volume threshold corroborates previous studies in the dog (35) and cat (16), both of which express β1- and β2-receptor subtypes (1, 33, 34). However, propranolol did not alter the micturition thresholds in the rat (31), which expresses the β3-receptor subtype (15, 47), underscoring both important species differences as well as the substantially higher affinity of propranolol for β1- and β2-receptor subtypes (21). The results indicate that β-adrenergic-mediated bladder inhibition does not play an important role in reflex excitation of the bladder by pudendal afferent stimulation but does play a major role in determining the volume thresholds.

α-Adrenergic block.

Blocking the α-adrenergic pathway with phentolamine increased the threshold volumes for distention-evoked and stimulation-evoked contractions. Although similar increases in the micturition volume threshold following α-adrenergic block were reported in the decerebrate dog (35) and conscious rat (43), others have reported decreases in the micturition volume threshold in cats (16, 18). One factor potentially responsible for these differences is peripheral (35, 43) vs. central (18) drug administration (25). As well, the results may reflect variation in the α-adrenergic receptor subtypes, as intrathecal injection of prazosin increased the micturition volume threshold in rats (25) but had little effect in cats (18). Further, differences in anesthesia across these studies may have influenced the effects of phentolamine. The current study was conducted under α-chloralose anesthesia, which affects spinal reflexes (40) and bladder behavior (39). Although the mechanism of how α-chloralose may affect the DNP-stimulation-evoked bladder reflexes remains unclear, similar reflexes are evoked in conscious, chronic spinal cord injury cats (41), suggesting that α-chloralose anesthesia is not critical to evoking these reflexes.

While the α-antagonist reduced the magnitude of stimulation-evoked and distention-evoked contractions by ∼25%, robust contractions were still evoked by pudendal afferent stimulation, suggesting that the α-adrenergic pathway played only a modulatory role in the stimulation-evoked response. The α-adrenergic innervation of the vesical ganglia is typically described as inhibitory, but there are two distinct actions of α-adrenergic receptors: α1-receptor-mediated facilitation of ganglionic transmission and α2-receptor-mediated inhibition of ganglionic transmission (2, 14, 26). Additionally, activation of the bladder neck and proximal urethra is mediated by α1-receptors (11), and phentolamine decreases bladder neck pressure and suppresses the increase in bladder neck pressure evoked by pudendal afferent stimulation (38).

These findings suggest two possible explanations for the increase in volume thresholds and decrease in contraction magnitude following α-block: loss of facilitation at the vesicle ganglia or loss of activation of the bladder neck. Block of α2-receptors (by the antagonist atipamezole) decreased bladder excitability (increased bladder capacity and residual urine) in conscious rats (24), suggesting that α2-receptor block may have contributed to the increase in micturition threshold and decrease in stimulation-evoked contraction magnitudes. The decrease in distension-evoked contraction magnitudes following phentolamine, while not significant, is consistent with phentolamine decreasing bladder excitability and not impairing the pudendal-to-bladder reflex. Regardless of the mechanism, the effects of α-block were not evident following hypogastric transection, providing further evidence that pudendal afferent stimulation-evoked modulation of α-adrenergic bladder activity does not contribute significantly to bladder excitation.

Hypogastric transection.

Bilateral hypogastric nerve transection was used as an alternate, nonselective means of blocking the sympathetic bladder innervation, and results were similar under surgical and pharmacological block. Hypogastric nerve transection decreased the DTV, consistent with previous findings (31, 35, 50) and also decreased the STV. Additionally, the decrease in volume thresholds was consistent with the volume threshold changes induced by β-block but contrary to the changes due to α-block, suggesting that the β-adrenergic pathway has greater influence over the micturition threshold than the α-adrenergic pathway.

The lack of effect of subsequent administration of adrenergic antagonists on the volume thresholds indicates that hypogastric transection provided functionally complete block of the sympathetic bladder innervation. The pelvic nerve also contains a significant sympathetic component (29), but this may have primarily a vasomotor function (20). The administration of the adrenergic antagonists subsequent to hypogastric nerve transection ensured substantial, if not complete, block of the sympathetic pathways to the bladder, and even under such conditions, robust bladder contractions were still evoked by pudendal afferent stimulation and distension, albeit at smaller bladder volume thresholds. As well, the ability to evoke robust bladder contractions by stimulation of pudendal afferents following hypogastric transection also rules out any role of nonadrenergic hypogastric bladder pathways (9) in the excitatory pudendal-to-bladder reflex.

Low-frequency stimulation of the DNP inhibited distention-evoked reflex contractions of the bladder as previously reported (41, 45). Inhibition of distention-evoked contractions was preserved following hypogastric transection and subsequent adrenergic antagonist administration, and the inhibition was comparable to inhibition evoked prior to hypogastric transection. Previously, it was reported that hypogastric transection reduced bladder inhibition evoked by pudendal nerve stimulation, but inhibition was recovered when the stimulation intensity was increased by factors of two to three (42). In the present study, stimulation intensity was equal to three times the threshold to evoke a reflex EMG response in the external anal sphincter, and the effect of stimulation intensity was not varied. These results suggest that the primary reflex pathways for bladder contraction and inhibition evoked by pudendal afferent stimulation do not engage adrenergic mechanisms.

Genitovesical reflex.

While previous results suggest a role of the sympathetic bladder pathways in the inhibitory genitovesical reflex (30, 42), our findings suggest that convergence of somatic (pudendal) and parasympathetic (pelvic) afferents is the pathway for reflex bladder excitation by pudendal afferent stimulation. Sympathetic block altered volume thresholds, but it did not abolish the ability to evoke bladder contractions at volume thresholds smaller than those for distension-evoked responses. This suggests that the excitatory genitovesical reflex results from converging spinal inputs from genital and pelvic afferents, providing increased excitatory input to pathways that activate preganglionic parasympathetic bladder efferents. Pelvic and pudendal afferents converge on interneurons in the sacral spinal cord (7, 22), providing a substrate for the excitatory genitovesical reflex. Additionally, the strong correlation between the bladder volume and the magnitude of contractions evoked by DNP stimulation provides evidence that increasing the level of pelvic afferent input drives increased pelvic efferent activity, implying convergence of the pudendal afferent and pelvic afferent inputs in the sacral spinal cord.

That reflex bladder excitation by pudendal afferent stimulation is mediated by the parasympathetic pelvic nerve is supported by the finding that the reflex is abolished by the nicotinic ganglionic blocker hexamethonium bromide. Further, the preservation of reflex bladder activation by pudendal afferent stimulation following acute spinal transection (4–6, 46, 49) and the subsequent abolition of stimulation-evoked contractions by hexamethonium bromide in the spinal transected animal, confirm the spinal origin of the DNP-bladder pathway.

Conclusion.

The sympathetic bladder pathway does not play a significant role in reflex excitation of the bladder by pudendal afferent stimulation, but sympathetic bladder innervation is important in determining the threshold volumes for stimulation-evoked and distention-evoked reflex bladder contractions. The excitatory pudendal-to-bladder reflex is mediated by increased activation of parasympathetic fibers arising from convergence of pelvic afferent and pudendal afferent fibers in the sacral spinal cord.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant R01-NS-050514.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Gilda Mills for outstanding technical assistance and Dr. Karl Thor for discussions on pharmacological interventions.

REFERENCES

- 1. Andersson KE. Pharmacology of lower urinary tract smooth muscles and penile erectile tissues. Pharm Rev 45:254–308, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Andersson KE. α1-Adrenoceptors and bladder function. Eur Urol 36,Suppl 1:96–102, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barrington FJF. The component reflexes of micturition in the cat, parts I and II. Brain 54:177–188, 1931 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boggs JW, Wenzel BJ, Gustafson KJ, Grill WM. Spinal micturition reflex mediated by afferents in the deep perineal nerve. J Neurophysiol 93:2688–2697, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boggs JW, Wenzel BJ, Gustafson KJ, Grill WM. Bladder emptying by intermittent electrical stimulation of the pudendal nerve. J Neural Eng 3:43–51, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boggs JW, Wenzel BJ, Gustafson KJ, Grill WM. Frequency-dependent selection of reflexes by pudendal afferents in the cat. J Physiol 577:115–126, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Coonan EM, Downie JW, Du HJ. Sacral spinal cord neurons responsive to bladder pelvic and perineal inputs in cats. Neurosci Lett 260:137–140, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Craggs M, McFarlane J. Neuromodulation of the lower urinary tract. Exp Physiol 84:149–160, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Creed KE. The role of the hypogastric nerve in bladder and urethral activity of the dog. Br J Pharmacol 65:367–375, 1979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Danuser H, Bemis K, Thor KB. Pharmacological analysis of the noradrenergic control of central sympathetic and somatic reflexes controlling the lower urinary tract in the anesthetized cat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 274:820–825, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. de Groat WC. Integrative control of the lower urinary tract: preclinical perspective. Br J Pharmacol 147, Suppl 2:S25–S40, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Groat WC, Nadelhaft I, Milne RJ, Booth AM, Morgan C, Thor K. Organization of the sacral parasympathetic reflex pathways to the urinary bladder and large intestine. J Auton Nerv Syst 3:135–160, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Groat WC, Saum WR. Sympathetic inhibition of the urinary bladder and of pelvic ganglionic transmission in the cat. J Physiol 220:297–314, 1972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. de Groat WC, Yoshiyama M, Ramage AG, Yamamoto T, Somogyi GT. Modulation of voiding and storage reflexes by activation of α1-adrenoceptors. Eur Urol 36, Suppl 1:68–73, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dolan JA, Muenkel HA, Burns MG, Pellegrino SM, Fraser CM, Pietri F, Strosberg AD, Largis EE, Dutia MD, Bloom JD, Bass AS, Tanikella TK, Cobuzzi A, Lai FM, Claus TH. β-3 Adrenoceptor selectivity of the dioxolane dicarboxylate phenethanolamines. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 269:1000–1006, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Edvardsen P. Nervous control of the urinary bladder in cats. III. Effects of autonomic blocking agents in the intact animal. Acta Physiol Scand 72:183–193, 1968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Edvardsen P. Nervous control of urinary bladder in cats. IV. Effects of autonomic blocking agents on responses to peripheral nerve stimulation. Acta Physiol Scand 72:234–247, 1968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Espey MJ, Downie JW, Fine A. Effect of 5-HT receptor and adrenoceptor antagonists on micturition in conscious cats. Eur J Pharmacol 221:167–170, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hallerback B, Glise H, Sjoqvist A. Reflex sympathetic inhibition of colonic motility in the cat. Scand J Gastroenterol 22:141–148, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hamberger B, Norberg KA. Studies on some systems of adrenergic synaptic terminals in the abdominal ganglia of the cat. Acta Physiol Scand 65:235–242, 1965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hoffmann C, Leitz MR, Oberdorf-Maass S, Lohse MJ, Klotz KN. Comparative pharmacology of human β-adrenergic receptor subtypes–characterization of stably transfected receptors in CHO cells. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 369:151–159, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Honda CN. Visceral and somatic afferent convergence onto neurons near the central canal in the sacral spinal cord of the cat. J Neurophysiol 53:1059–1078, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Horvath EE, Yoo PB, Amundsen CL, Webster GD, Grill WM. Conditional and continuous electrical stimulation increase cystometric capacity in persons with spinal cord injury. Neurourol Urodyn 9:401–407, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ishizuka O, Mattiasson A, Andersson KE. Role of spinal and peripheral α2-adrenoceptors in micturition in normal conscious rats. J Urol 156:1853–1857, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jeong MS, Lee JG. The role of spinal and peripheral α1- and α2-adrenoceptors on bladder activity induced by bladder distension in anaesthetized rat. BJU Int 85:925–931, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Keast JR, Kawatani M, de Groat WC. Sympathetic modulation of cholinergic transmission in cat vesical ganglia is mediated by α1- and α2-adrenoceptors. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 258:R44–R50, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kirkham AP, Shah NC, Knight SL, Shah PJ, Craggs MD. The acute effects of continuous and conditional neuromodulation on the bladder in spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 39:420–428, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Koley B, Koley J, Saha JK. The effects of nicotine on spontaneous contractions of cat urinary bladder in situ. Br J Pharmacol 83:347–355, 1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kuo DC, Hisamitsu T, de Groat WC. A sympathetic projection from sacral paravertebral ganglia to the pelvic nerve and to postganglionic nerves on the surface of the urinary bladder and large intestine of the cat. J Comp Neurol 226:76–86, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lindström S, Fall M, Carlsson CA, Erlandson BE. The neurophysiological basis of bladder inhibition in response to intravaginal electrical stimulation. J Urol 129:405–410, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Maggi CA, Santicioli P, Meli A. Sympathetic inhibition of reflex activation of bladder motility during filling at a physiological-like rate in urethane anesthetized rats. Neurourol Urodyn 4:37–45, 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 32. McMahon SB, Morrison JF. Factors that determine the excitability of parasympathetic reflexes to the cat bladder. J Physiol 322:35–43, 1982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Morita T, Ando M, Kihara K, Oshima H. Species differences in cAMP production and contractile response induced by β-adrenoceptor subtypes in urinary bladder smooth muscle. Neurourol Urodyn 12:185–190, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nergårdh A. Characterization of the β-adrenergic receptors in the lower urinary tract of the cat. Scand J Urol Nephrol 11:211–217, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nishizawa O, Fukuda T, Matsuzaki A, Moriya I, Satoh S, Tsuchida S. Adrenergic influences on the voiding cycle in the decerebrated dog. Neurourol Urodyn 5:505–513, 1986 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Peng CW, Chen JJ, Cheng CL, Grill WM. Role of pudendal afferents in voiding efficiency in the rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 294:R660–R672, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Poirier M, Riffaud JP, Lacolle JY, Dupont C. Effects of five α-blockers on the hypogastric nerve stimulation of the canine lower urinary tract. J Urol 140:165–167, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Reitz A, Schmid DM, Curt A, Knapp PA, Schurch B. Afferent fibers of the pudendal nerve modulate sympathetic neurons controlling the bladder neck. Neurourol Urodyn 22:597–601, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rudy D, Downie J, McAndrew J. α-Chloralose alters autonomic reflex function of the lower urinary tract. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 261:R1560–R1567, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shimamura M, Yamauchi T, Aoki M. Effects of chloralose anesthesia on spinal reflexes. Jpn J Physiol 18:788–797, 1968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tai C, Shen B, Wang J, Chancellor MB, Roppolo JR, de Groat WC. Inhibitory and excitatory perigenital-to-bladder spinal reflexes in the cat. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294:F591–F602, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tai C, Smerin SE, de Groat WC, Roppolo JR. Pudendal-to-bladder reflex in chronic spinal-cord-injured cats. Exp Neurol 197:225–234, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ukimura O. Effects of intravesically administered anticholinergics, β-adrenergic stimulant and α-adrenergic blocker on bladder function in unanesthetized rats. Tohoku J Exp Med 170:251–260, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wheeler JS, Walter JS, Zaszczurynski PJ. Bladder inhibition by penile nerve stimulation in spinal cord injury patients. J Urol 147:100–103, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Woock JP, Yoo PB, Grill WM. Activation and inhibition of the micturition reflex by penile afferents in the cat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 294:R1880–R1889, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Woock JP, Yoo PB, Grill WM. Intraurethral stimulation evokes bladder responses via 2 distinct reflex pathways. J Urol 182:366–373, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Woods M, Carson N, Norton NW, Sheldon JH, Argentieri TM. Efficacy of the β3-adrenergic receptor agonist CL-316243 on experimental bladder hyperreflexia and detrusor instability in the rat. J Urol 166:1142–1147, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yoo PB, Klein SM, Grafstein NH, Horvath EE, Amundsen CL, Webster GD, Grill WM. Pudendal nerve stimulation evokes reflex bladder contractions in persons with chronic spinal cord injury. Neurourol Urodyn 26:1020–1023, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yoo PB, Woock JP, Grill WM. Bladder activation by selective stimulation of pudendal nerve afferents in the cat. Exp Neurol 212:218–225, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yoshiyama M, de Groat WC. Effect of bilateral hypogastric nerve transection on voiding dysfunction in rats with spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol 175:191–197, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]