Abstract

Mechanical ventilation is a risk factor for the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in premature infants. Fifteen minutes of high tidal volume (Vt) ventilation induces inflammatory cytokine expression in small airways and lung parenchyma within 3 h. Our objective was to describe the temporal progression of cytokine and maturation responses to lung injury in fetal sheep exposed to a defined 15-min stretch injury. After maternal anesthesia and hysterotomy, 129-day gestation fetal lambs (n = 7–8/group) had the head and chest exteriorized. Each fetus was intubated, and airway fluid was gently removed. While placental support was maintained, the fetus received ventilation with an escalating Vt to 15 ml/kg without positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) for 15 min using heated, humidified 100% nitrogen. The fetus was then returned to the uterus for 1, 6, or 24 h. Control lambs received a PEEP of 2 cmH2O for 15 min. Tissue samples from the lung and systemic organs were evaluated. Stretch injury increased the early response gene Egr-1 and increased expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines within 1 h. The injury induced granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor mRNA and matured monocytes to alveolar macrophages by 24 h. The mRNA for the surfactant proteins A, B, and C increased in the lungs by 24 h. The airway epithelium demonstrated dynamic changes in heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) over time. Serum cortisol levels did not increase, and induction of systemic inflammation was minimal. We conclude that a brief period of high Vt ventilation causes a proinflammatory cascade, a maturation of lung monocytic cells, and an induction of surfactant protein mRNA.

Keywords: cytokines, tidal volume, bronchopulmonary dysplasia

mechanical ventilation with large tidal volumes causes lung injury and poor pulmonary outcomes in adults (1). In preterm infants, mechanical ventilation is associated with the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) (44), and strategies to reduce mechanical ventilation at birth tend to decrease BPD (15, 34). The newborn infant is more susceptible to lung injury from mechanical ventilation at birth because the lung is transitioning from fluid to air filled (24). Although clinicians attempt to provide low tidal volumes in the delivery room, the tidal volumes delivered are not measured and are likely high (40, 42). Clinicians using a T-piece respirator to ventilate preterm infants (<32 wk) provided tidal volume breaths between 0 and 31 ml/kg (42). As few as six large-tidal volume breaths at birth can eliminate the response to surfactant treatment in preterm sheep (8). Since the majority of preterm infants with birth weights <1,500 g receive some ventilatory support at birth (14), understanding the mechanisms and progression of injury should suggest strategies to decrease that injury.

We have used a fetal sheep model to explore the effects of large-tidal volume ventilation at birth (19). Fifteen minutes of ventilation with escalating tidal volumes to 15 ml/kg caused lung inflammation and increased serum amyloid A3 mRNA in the liver within 3 h. The lung injury was most evident in the large and small airways (17). Changes in the smooth muscle heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) surrounding cartilaginous airways suggested repetitive distension of airways during resuscitation and recruitment of functional residual capacity. Large airways also had epithelial sloughing with localization of IL-1β mRNA in epithelial cells (17). The small airways had early growth response protein 1 (Egr-1) activation and subsequent production of other proinflammatory cytokines [monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and IL-6] in the mesenchyme surrounding smaller airways (17). Since fetal sheep do not have mature alveolar macrophages (31), the proinflammatory cytokines are likely produced by parenchymal cells. In utero ventilation of very immature sheep for 6 h with lower tidal volumes created a BPD model with decreased secondary septal crests and increased smooth muscle staining (2, 38).

We previously found that fetal exposure to chorioamnionitis and inflammation induced lung maturation and maturation of monocytes to macrophages in the fetal lung (31). We hypothesized that a stretch-induced inflammatory response in the fetal lung might also induce lung maturation. We now have used the fetal ventilation model to evaluate the dynamic progression of inflammation and induction of maturation caused by a defined stretch injury. By maintaining the placental circulation and returning the fetus to the uterus after resuscitation, we report the progression of injury without the confounding effects of oxygen exposure or continued ventilation (19).

METHODS

The investigations were approved by the Animal Ethics Committees of the University of Western Australia and Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center.

Fetal ventilation procedure.

Date-mated Merino ewes at 129 ± 1 days of gestational age were premedicated with ketamine (20 mg/kg im) and xylazine (0.5 mg/kg im) before induction of maternal anesthesia with inhaled isofluorane. Each ewe was mechanically ventilated in a supine position. The fetal head and chest were exteriorized through a midline hysterotomy while placental blood flow was maintained (19). The fetus was orally intubated, and airway fluid (∼30 ml) was passively removed before mechanical ventilation (Babylog 8000+; Dräger, Lübeck, Germany). The fetuses randomized to the high-tidal volume (Vt) ventilation had Vt targets of 5 ml/kg at 5 min, 10 ml/kg at 10 min, and 15 ml/kg by 15 min, with a peak inspiratory pressure limit of 55 cmH2O. An escalating Vt was used to allow for some clearance of lung fluid and to minimize severe injury. The lambs were ventilated at 40 breaths/min, with a PEEP of 0 cmH2O and an inspiratory time of 0.7 s using heated, humidified 100% nitrogen. Control lambs received no ventilation and a PEEP of 2 cmH2O for 15 min. After the intervention, the fetus was returned to the uterus, and the uterus and maternal abdomen were closed. The ewe recovered from general anesthesia, and fetal tissues were collected at 1 (n = 7), 6 (n = 7), or 24 h (n = 8) after the 15-min intervention. Tissues from control lambs (n = 2 at 1 h, n = 2 at 6 h, and n = 3 at 24 h) were also collected.

Lung processing and bronchoalveolar lavage analysis.

At autopsy, a deflation pressure-volume curve was measured from a gas inflation to 40 cmH2O pressure (23). Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) of the left lung was used for measurements of total protein (33), MCP-1 by ELISA, IL-1β by ELISA, IL-6 by ELISA, and differential cell counts from cytospins. Tissue from the left lung was snap frozen for RNA isolation. The entire right lung was inflation fixed with 10% formalin for 1 h at 30 cmH2O (32). The lung was then segmented into right upper lobe, nondependent right middle lobe, dependent right middle lobe, and dependent right lower lobe, fixed in 10% formalin, and paraffin embedded. The dependent region was defined as a ventral region of lung as the lamb was ventilated in a supine position. Injury scoring was done on segmental regions of lungs of 1-h animals by a blinded scorer (18).

Quantitative RT-PCR.

mRNA was extracted from left lung tissue and thymus with TRIzol (Invitrogen) and treated with DNase. cDNA was produced from 1 mg of mRNA using the Verso cDNA kit (Thermoscientific). Custom TaqMan gene primers (Applied Biosystems) were designed from ovine sequences for IL-1β, IL-1 receptor agonist (IL-1ra), IL-6, MCP-1, MCP-2, Egr-1, HSP70, granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), a smooth muscle actin-γ (SMAγ), and surfactant proteins A, B, and C. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed with 25 ng of cDNA using TaqMan Master mix in a 25-μl reaction on a 7300 RT-PCR machine and software (Applied Biosystems). 18S primers (Applied Biosystems) were used for internal loading control, and results are reported as relative increase over the mean for control animals.

Immunohistochemistry/in situ hybridization.

Immunostaining protocols used paraffin sections (5 μm) of formalin-fixed tissues that were pretreated with 3% hydrogen peroxide to inactivate endogenous peroxidases (28, 29). The sections were incubated with anti-human Egr-1 (1:250 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) anti-mouse (1:250 dilution; BD Transduction), anti-mouse Pu.1 (1: 250 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-mouse α-SMA (1:10,000 dilution; Sigma), or rabbit anti-ovine MCP-1 (1:1,000 dilution; Seven Hills Bioreagents) in 4% normal goat serum overnight, followed by biotin-labeled secondary antibody. Immunostaining was visualized using a Vectastain ABC Peroxidase Elite kit to detect the antigen-antibody complexes (Vector Laboratories). The antigen detection was enhanced with nickel-diaminobenzidine followed by Tris-cobalt, and the nuclei were counterstained with nuclear fast red or eosin (Egr-1) (29).

In situ localization of mRNA was performed with digoxigenin-labeled antisense sheep riboprobes for HSP70, SMA-γ, or GM-CSF (Roche). Briefly, digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes (sense and antisense) were synthesized from cDNA templates using DIG RNA labeling kits (Roche) and diluted in hybridization buffer to a final concentration of 1 μg/ml. The sections were pretreated with 4% paraformaldehyde, treated with proteinase K, and hybridized with the probe overnight at 49–62°C, based on the GC content of probe. Sections were washed with formamide, treated with RNase A (100 μg/ml), and then blocked with 10% horse serum. After incubation overnight at 4°C with anti-digoxigenin antibody (Roche), the slides were developed with NBT-BCIP (Roche) in dark cases. The slides were monitored for color development and then stopped with Tris-EDTA buffer. Controls for specificity of riboprobe binding included use of the homologous (sense) probe. Percent staining of α-SMA and SMA-γ were quantified using Metamorph 3.5 (Universal Imaging) on random selected images.

Blood analysis.

Fetal blood was collected at the end of the 15-min ventilation procedure and at delivery. Complete blood cell counts were done on delivery blood, and plasma was snap frozen. A MCP-1 ELISA was measured with anti-ovine MCP-1 antibodies on plasma and BALF (43). Plasma cortisol was extracted with ether acetate and quantified by competitive binding ELISA (Oxford Biomedical Research).

Data analysis and statistics.

Results are means ± SE. Statistics were analyzed with InStat (GraphPad) using Student's t-test, the Mann-Whitney nonparametric test, or ANOVA when appropriate. Significance was accepted as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

All the lambs survived the fetal ventilation, return to the uterus, and the interval to delivery. There were no differences in birth weights between groups, and all ventilated animals received similar escalating Vt by the end of the 15-min procedure (Table 1). Control lambs, who received only a PEEP of 2 cmH2O and no Vt, had an increased venous Pco2 after the 15-min treatment interval (Table 1). This may represent some placental insufficiency due to maternal anesthesia. The ventilated lambs may have had partial correction of hypercapnia. The peak pressures needed for the Vt were the maximum value of 55 cmH2O in many animals, and thus the values for tidal volume per kilogram at 15 min were somewhat lower than the target of 15 ml/kg. Since the entire fetal chest was exteriorized, lung expansion was limited by the low compliance of the lungs and not chest compression. The preterm fetuses did not receive antenatal steroids or surfactant treatment, and low compliance would be expected.

Table 1.

Characteristics and ventilation parameters

| Vt, ml |

Blood Gases |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | n | BW, kg | 5 min | 10 min | 15 min | PIP | pH | PvCO2 | PvO2 |

| Controls | 7 | 3.6 ± 0.1 | No VT PEEP 2 cmH20 | 7.16 ± 0.04 | 81 ± 7 | 17 ± 2 | |||

| 1 h | 7 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 9.3 ± 0.4 | 12.4 ± 0.4 | 53 ± 1 | 7.25 ± 0.03 | 60 ± 4* | 13 ± 2 |

| 6 h | 7 | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 5.6 ± 0.4 | 9.4 ± 0.7 | 13.1 ± 1.4 | 48 ± 3 | 7.20 ± 0.06 | 65 ± 6 | 11 ± 1 |

| 24 h | 8 | 3.6 ± 0.1 | 5.2 ± 0.2 | 9.5 ± 0.3 | 13.0 ± 0.5 | 52 ± 2 | 7.26 ± 0.02* | 60 ± 3* | 18 ± 3 |

Values are means ± SE; n = no. of fetal lambs. BW, body weight; Vt, tidal volume, determined per kilogram of lung tissue; PIP, peak inspiratory pressure, determined at 15 min of ventilation; PvCO2 and PvO2, venous partial pressures of carbon dioxide and oxygen, respectively, determined at 15 min of ventilation. Controls had no Vt and a positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) of 2 cmH2O.

P < 0.05 vs. controls.

Lung inflammation.

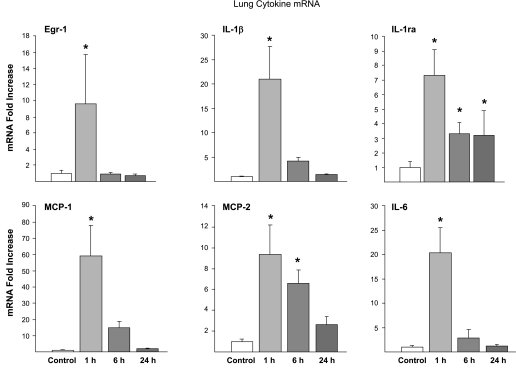

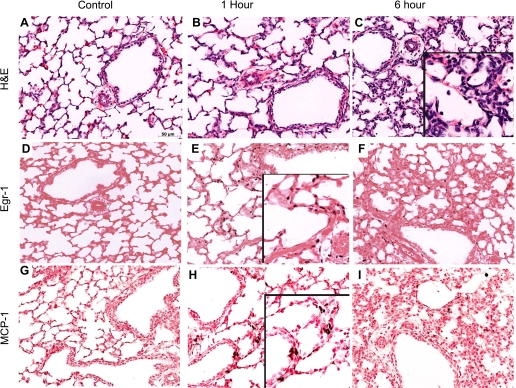

Proinflammatory cytokine mRNAs for IL-1β, IL-6, MCP-1, and MCP-2 were increased 1 h after the 15-min stretch injury (Fig. 1). These mRNA levels decreased by 6 h and returned to near baseline by 24 h after the high-Vt injury. Interestingly, mRNA for the anti-inflammatory IL-1ra was also induced by the 15-min stretch injury and remained elevated at 24 h. The high-Vt ventilation caused alveolar wall thickening, less alveolar expansion, and inflammatory cell infiltrates (Fig. 2, A–C). Egr-1 mRNA increased at the 1-h time point, and prominent Egr-1 protein was localized to the cells surrounding the airways in all 1-h animals (Fig. 2E). Egr-1 protein decreased by 6 h after the stretch injury (Fig. 2F). MCP-1 protein was localized to the regions surrounding the small airways by 1 h after the stretch injury (Fig. 2H) and to the inflammatory cells by 6 h (Fig. 2I). MCP-1 protein was not identified at 24 h. BALF MCP-1 protein increased from very low levels (0.01 ± 0.01 ng/ml) in controls to 52 ± 8 ng/ml at 1 h and 37 ± 5 ng/ml at 6 h and remained high at 12 ± 5 ng/ml at 24 h after ventilation (P < 0.05 vs. control at all times). IL-1β and IL-6 protein in the BALF did not significantly increase at 1, 6, or 24 h.

Fig. 1.

Early growth response protein 1 (Egr-1) and cytokine mRNA expression in lung over time. Egr-1 mRNA increased 1 h after 15 min of high-tidal volume (Vt) ventilation and returned to baseline by 6 h. The proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1, and MCP-2 mRNA all increased by 1 h. The counterregulatory molecule IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra) also increases at 1 h and remained elevated 24 h after the stretch injury. mRNA level expressed as the degree of change (fold increase) was determined from cDNA using quantitative RT-PCR, with mean values of controls set to 1. *P < 0.05 vs. controls.

Fig. 2.

Lung inflammation, Egr-1, and MCP-1 protein localization. Control lung (A) demonstrated no inflammation and thin airway septations on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Airway wall thickenings were apparent by 1 h after the stretch injury (B) with continued congestion and inflammation by 6 h (C, inset). Egr-1 protein was expressed in the nucleus of cells surrounding the small airways at 1 h (E, inset) and had decreased by 6 h (F). MCP-1 protein was in the mesenchyme at 1 h (H, inset) and in inflammatory cells at 6 h (F). Egr-1 and MCP-1 were not increased in control animals (D and G).

Lung maturation.

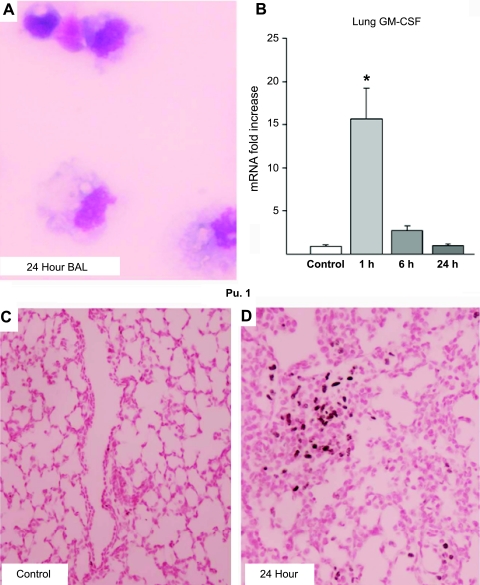

Inflammatory cells in the BALF increased, with initial increases in neutrophils and monocytes by 1 h and a transition to foamy macrophages by 24 h after the high-Vt injury (Table 2 and Fig. 3A). The monocyte-to-alveolar macrophage maturation was likely driven by GM-CSF, since the mRNA levels increased in lungs in the 1-h group (Fig. 3B). GM-CSF mRNA was localized by in situ to occasional cells within the lung parenchyma in 1-h animals (data not shown). Pu.1 staining increased in the lung parenchyma over time (Fig. 3D) compared with controls (Fig. 3C), demonstrating maturation of lung inflammatory cells. Myloperoxidase was localized to inflammatory cells and increased from 1 to 24 h, whereas iNOS was not induced by ventilation (data not shown). High-Vt ventilation also increased the mRNA for surfactant proteins A, B, and C mRNA (Table 2). Increased total protein in BALF also indicated injury at 6 and 24 h (Table 2).

Table 2.

Inflammation in BAL fluid and lung tissue surfactant protein mRNA

| BAL cells/kg, ×106 |

Lung mRNA Fold Increase |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | BAL Protein, mg/kg | Neutrophils | Monocytes | Macrophages | SP A | SP B | SP C |

| Control | 41 ± 15 | 0.5 ± 0.5 | 0.9 ± 1.4 | 0.1 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.3 |

| 1 h | 73 ± 19 | 40 ± 28* | 10.2 ± 7.9* | 9 ± 5* | NT | NT | NT |

| 6 h | 94 ± 15* | 35 ± 8* | 2.6 ± 1.9† | 44 ± 14*† | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.3 |

| 24 h | 80 ± 13* | 16 ± 10* | 3.1 ± 3.3† | 46 ± 7*† | 1.8 ± 0.2* | 2.0 ± 0.2* | 3.0 ± 0.5* |

Values are means ± SE. BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage; SP, surfactant protein; NT, not tested.

P < 0.05 vs. controls.

P < 0.05 vs. animals at 1 h.

Fig. 3.

Maturational signals from initiation of ventilation. A: representative image of large, foamy macrophage-like cells in BALF 24 h after the stretch injury. B: granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) mRNA increased at 1 h in lung after stretch injury and then returned to baseline. Pu.1 protein was minimal in fetal control lungs (C) but increased in the lung parenchyma by 24 h after stretch injury (D).

Heat shock protein and smooth muscle actin.

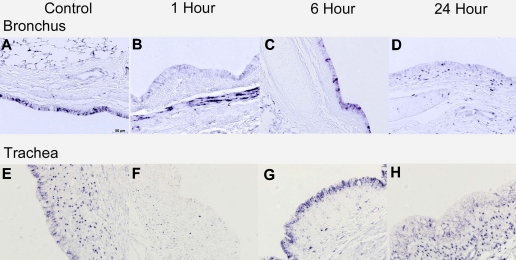

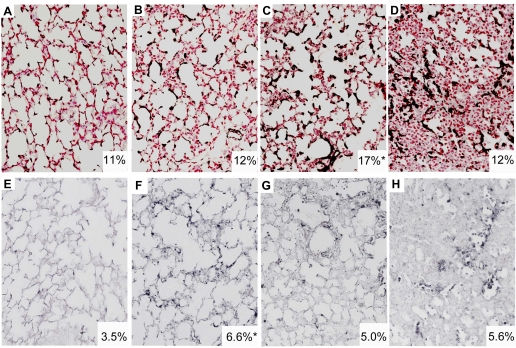

The chaperone protein HSP70 and smooth muscle actin also changed dynamically after ventilation injury. HSP70 mRNA was localized to bronchial epithelium of the lung in control animals (Fig. 4A). Ventilation decreased the mRNA expression in bronchial epithelium and increased the signal within the airway smooth muscle in the 1-h animals (Fig. 4B). By 6 h, the HSP70 mRNA had returned to bronchial epithelium and was qualitatively increased compared with controls (Fig. 4C). HSP70 mRNA localization was similar in the 24-h animals and control animals. HSP70 protein had a similar pattern in bronchial epithelium but was not well visualized in smooth muscle (data not shown). Similar in situ localization of HSP70 mRNA occurred in the tracheal epithelium lining, but there were no increases in tracheal smooth muscle (Fig. 4F). Tracheal sections also did not show inflammation, Egr-1, or MCP-1 protein increases compared with controls. Small increases in α-SMA in the alveolar ducts were measured at 6 h (16.9 ± 2.0% tissue staining) relative to controls (10.8 ± 0.9% tissue staining, P < 0.05), but α-SMA returned to baseline at 24 h (11.9 ± 1.9% tissue staining) (Fig. 5, A–D). SMAγ is an actin isoform only found in smooth muscle. The mRNA signal increased in the parenchyma surrounding smaller airways in the peripheral lung at 1 h (6.7 ± 0.8% staining, P < 0.05) vs. controls (3.5 ± 0.9) (Fig. 5, E and F), although no overall increase was seen on RT-PCR using lung tissue.

Fig. 4.

Heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) mRNA expression in the trachea and bronchus. Bronchial epithelium of control lambs expressed HSP70 (A), which was lost 1 h after ventilation (B). HSP70 mRNA was induced in bronchial epithelium at 6 h (C) and returned to baseline by 24 h (D). A similar pattern was seen in the tracheal epithelium (E–H). HSP70 mRNA was induced in the smooth muscle surrounding the larger airways at 1 h after intervention (B) but had resolved by 6 h (C).

Fig. 5.

Smooth muscle actin (SMA) staining in lung parenchyma. A–D: α-SMA protein was increased in the peripheral lungs at 6 h (C) compared with controls (A). E–H: SMAγ mRNA increased in the peripheral lung in animals at 1 h (F) compared with controls (E). Insets: average percentage of tissue staining per high-powered field. *P < 0.05 vs. controls.

Regional differences in lung injury.

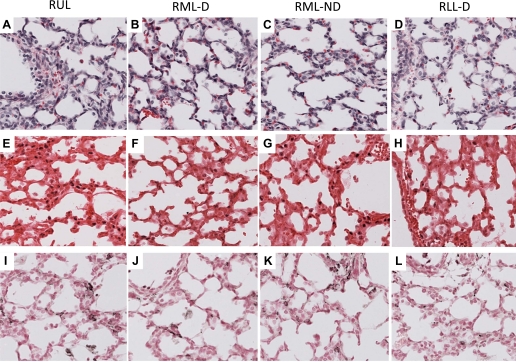

The right lung was formalin fixed for 1 h and then sampled from the right upper lobe, right middle lobe dependent and nondependent regions, and right lower lobe dependent region. There were no differences in the lung injury scores on hematoxylin and eosin staining between the lung regions 1 h after injury (Fig. 6, A–D). Inflammatory cells were seen in airways of all sections. Egr-1 protein was localized to the cells surrounding the small airways in all regions, with no differences seen (Fig. 6, E–H). MCP-1 protein was localized to airways and some inflammatory cells in all regions (Fig. 6, I–L). HSP70 mRNA was lost from bronchial epithelium and induced in smooth muscles surrounding airways in all lung regions (data not shown). Therefore, there was no regional difference in the localization of injury with the fetal ventilation.

Fig. 6.

Regional staining for H&E, Egr-1, and MCP-1 protein did not differ at 1 h. A–D: similar patterns of injury were seen between the right upper lobe (RUL), right middle lobe dependent (RML-D), right middle lobe nondependent (RML-ND), and right lower lobe dependent region (RLL-D) of the lung at 1 h. Egr-1 protein (E–H) and MCP-1 protein (I–L) staining patterns also did not differ between dependent and nondependent regions.

Systemic responses to ventilation.

There were no differences between the controls and 1-, 6-, or 24-h ventilated animals for the peripheral white blood cells counts and differentials. Although inflammatory cells and MCP-1 protein increased in the BALF, plasma MCP-1 levels did not change. Plasma cortisol values after 15-min ventilation were very low and not elevated in the ventilated lambs (1.6 ± 0.3 μg/dl) compared with the control animals (1.2 ± 0.2 μg/dl). There were also no changes in the thymus for mRNA for the cytokines GM-CSF, IL-1β, or IL-6.

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated the progression of lung injury in response to a brief, high-Vt ventilation in these preterm fetal lambs. We avoided oxidative stress, by using nitrogen as the gas for ventilation, and the confounding effects of continued ventilation, by maintaining placental circulation (19). A cascade of both pro- and anti-inflammatory signals was initiated by the 15-min intervention and triggered maturation pathways that were independent of plasma cortisol. This fetal model permits an evaluation of a brief period of standardized volutrauma and identifies inflammatory pathways that may contribute to development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia in premature infants.

Stretch injury to the fetal lamb leads to lung inflammation characterized by induction of multiple classes of cytokines and chemokines. Stretch injury causes Egr-1 activation through MAP kinase phosphorylization (36). Egr-1 signaling, as seen in these animals, can then activate a variety of pathways, including proinflammatory cytokines (37). Initiation of ventilation in preterm sheep also increases multiple early response genes, including CYR61 and CTGF (46). Similar activation of multiple early response genes occurs in adult rats ventilated with high Vt (11). The simultaneous induction of both IL-1β and its endogenous regulatory molecule, IL-1ra, demonstrates the ability of the fetal lung to modulate inflammation. IL-1ra mRNA induction within 1 h could be either an initial activation by the high-Vt ventilation or an anti-inflammatory response, which continues to 24 h. The cells initially recruited to the lungs are neutrophils and monocytes, with progressive recruitment or maturation of monocytes into macrophages. There are very few alveolar macrophages in the lungs of preterm sheep, but macrophages increase rapidly after birth in sheep and other mammals (30). By 24 h after the 15-min high-Vt ventilation, the lung had increased Pu.1 staining, which is likely due to the increase in GM-CSF (7). Preterm fetal sheep exposed to intra-amniotic lipopolysaccharide (LPS) have increased lung GM-CSF and Pu.1 signaling and increased alveolar macrophages (31). Stretch injury induces many pathways that overlap with LPS-induced inflammation, and the multiple types of pathways may make selective blockade of inflammatory pathways difficult. We have attempted to decrease the inflammatory response to stretch injury with postnatal steroids (dexamethasone, cortisol) and inhibitors of NF-κB, IL-1, and IL-8 without success (16, 20). Antenatal betamethasone decreased, but did not eliminate, the inflammatory process (20).

The increase in surfactant protein mRNA synthesis could be a response to 1) a stretch injury to type II cells, 2) the proinflammatory cytokines or GM-CSF released in response to stretch, or 3) the inflammatory cells recruited to the lung. When stimulated by stretch in vitro, fetal rat type II cells increase surfactant protein mRNA by activation of the MAP kinases ERK1/2 (41). Activation of these kinases also induces Egr-1 (36). The 15-min stretch injury also leads to increased GM-CSF mRNA production within 1 h. GM-CSF receptors are present on the type II cells (9), and GM-CSF modulates surfactant homeostasis (13), suggesting the production of GM-CSF could lead to maturation. GM-CSF, when given to pregnant rats, resulted in fetal lung maturation and alveolar septal thinning similar to antenatal betamethasone (4). GM-CSF is also increased in the BALF of very low birth weight infants who develop BPD compared with infants without BPD (5). The induction of the surfactant proteins could result from the inflammatory cells recruited to the lung. Fetal sheep exposed to intra-amniotic LPS require an inflammatory cell influx into the lungs for increases in surfactant protein mRNA (27). The increases in surfactant protein mRNA measured 24 h after fetal resuscitation were similar to the increases that occurred 24 h after exposure to intra-amniotic LPS (3). Similar to LPS-induced lung maturation (26), the maturational effects of the brief fetal ventilation injury were not mediated through increased plasma cortisol.

The epithelium of the fetal airway modulates the acute response protein HSP70 in response to a stretch injury. HSP70 is an endogenous ligand for Toll-like receptor 4 and can trigger an inflammatory response (47). We reported a loss of HSP70 protein and mRNA from the bronchial epithelium and an induction of mRNA in the bronchial smooth muscle with 3 h of ventilation (19). Although HSP70 is released into airways with stretch (10, 17), the bronchial and tracheal airway epithelium responded with increased mRNA expression at 6 h. A similar airway response has been seen in rats ventilated with high Vt (11). Chong et al. (10) demonstrated that minimal distention of isolated sheep tracheas leads to appearance of HSP70 into lung fluid, suggesting that our control animals, receiving a distending pressure of 2 cmH2O, may have had some HSP70 release. We choose to use a distending pressure for 15 min because the fetal lung is normally distended by lung fluid to a pressure of 2–3 cmH2O (35). Other investigators have demonstrated the ability of fetal airway epithelium to recover from injury. In utero ventilation of very immature sheep for 12 h increased mucin-producing cells in the airways, and these changes had resolved by 7 days (38). Airway injury and epithelial disruption also seen in these animals at 6 and 12 h after ventilation had resolved by 7 days (38). Prolonged ventilation (6–12 h) of very immature lambs, with a lower Vt (4–6 ml/kg) than used in this study, increased staining of smooth muscle actin within the lungs (2). We have demonstrated subtle changes in smooth muscle actin in these animals, although the percent staining was lower than that in younger control lambs (11%) (2). The changes in the airway bronchial epithelium and smooth muscle demonstrate an airway response to stretch injury in the fetal lamb. This progression of injury, and possible repair, demonstrates how ventilation initiates prolonged responses in the preterm.

Evaluation of the lung regions did not demonstrate differential injury between the nondependent and dependent regions of the lung. We expected to find increased markers of injury in the nondependent regions, where higher local Vt might have caused more injury. With prolonged ventilation after high-Vt resuscitation, we often find larger areas of hemorrhage and plural blebs along the nondependent regions of the preterm lamb lung (unpublished observations). The upper pole of the sheep lung develops surfactant earlier than lower regions of the lungs, as do human lungs (25). Rabbit pups also demonstrate different regions of airspace recruitment during initiation of ventilation at birth, with upper lobes opening earlier than the remainder of the lung (21). Ventilation of saline-lavaged rabbits demonstrated differences in the type of cytokine activated between dependent and nondependent regions of the lungs, with IL-8 increased in dependent lung and MCP-1 increased in nondependent lung (39).The damage caused by the ventilation of fluid-filled, surfactant-deficient lungs with large Vt may have reached a threshold for inflammation in all regions and masked the potential to detect regional differences. Because protein staining for Egr-1 and MCP-1 did not differ between regions for the 1 h group, no evaluation was done on later time points.

A limitation of our study, as with many large animal studies, is the inability to prove causality between the associations of airway stretch and maturation of the fetal lung. Since the first time point in this study is 1 h after completion of ventilation, the initial signaling that increased cytokine and chemokine production was not evaluated. In vitro models of both airway epithelial and endothelial cell lines demonstrate that stretch leads to production of IL-8 (22, 45). Multiple pathways are activated by stretch, with Egr-1 and IL-6 likely activated through MAP kinases and HSP70 and IL-1β being activated through NF-κB (12). Future studies examining earlier time points after stretch injury may lead to a better understanding of molecular pathways that can result in injury of the preterm lung at birth.

The initiation of ventilation with large tidal volume caused lung inflammation within 1 h and maturation of inflammatory cells within 24 h. This brief stretch injury to the fetal sheep lung also causes changes in the airway epithelium and increases in surfactant proteins. These maturational changes occur in absence of an increase in plasma cortisol and are likely due to the local production of chemokines, such as GM-CSF, or direct effects on type II cells. Premature infants exposed to ventilation at birth have an increased risk of developing bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Our current study demonstrates the ability of isolated stretch to activate both maturational chemokines and pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines. The study stresses the complexity of pathways activated by ventilation and the need to avoid excessive ventilation of extremely premature infants at birth.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HD-12714 and K08 HL097085 (to N. H. Hillman), a Viertiel Senior Medical Research Fellowship (to J. J. Pillow), a National Heart Foundation of Australia/National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Fellowship (to G. R. Polglase), and the Women and Infants Research Foundation.

G. R. Polglase is now at Monash University, Melbourne, Australia.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Gabby Mask, Fraser Murdoch, and Talia Sanders for assistance with anesthesia and pain control and Amy Whitescarver and Megan McAuliffe for work in the laboratory.

REFERENCES

- 1. The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury, and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 342: 1301–1308, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Allison BJ, Crossley KJ, Flecknoe SJ, Davis PG, Morley CJ, Harding R, Hooper SB. Ventilation of the very immature lung in utero induces injury and BPD-like changes in lung structure in fetal sheep. Pediatr Res 64: 387–392, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bachurski CJ, Ross GF, Ikegami M, Kramer BW, Jobe AH. Intra-amniotic endotoxin increases pulmonary surfactant components and induces SP-B processing in fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 280: L279–L285, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baytur YB, Ozbilgin K, Yuksel H, Kose C. Antenatal administration of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor increases fetal lung maturation and endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression in the fetal rat lung. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 136: 171–177, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Been JV, Debeer A, van Iwaarden JF, Kloosterboer N, Passos VL, Naulaers G, Zimmermann LJ. Early alterations of growth factor patterns in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from preterm infants developing bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Pediatr Res 67: 83–89, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Berclaz PY, Carey B, Fillipi MD, Wernke-Dollries K, Geraci N, Cush S, Richardson T, Kitzmiller J, O'Connor M, Hermoyian C, Korfhagen T, Whitsett JA, Trapnell BC. GM-CSF regulates a PU.1-dependent transcriptional program determining the pulmonary response to LPS. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 36: 114–121, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bjorklund LL, Ingimarsson J, Curstedt T, John J, Robertson B, Werner O, Vilstrup CT. Manual ventilation with a few large breaths at birth compromises the therapeutic effect of subsequent surfactant replacement in immature lambs. Pediatr Res 42: 348–355, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bry K, Hallman M, Teramo K, Waffarn F, Lappalainen U. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in amniotic fluid and in airway specimens of newborn infants. Pediatr Res 41: 105–109, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chong E, Dysart KC, Chidekel A, Locke R, Shaffer TH, Miller TL. Heat shock protein 70 secretion by neonatal tracheal tissue during mechanical ventilation: association with indices of tissue function and modeling. Pediatr Res 65: 387–391, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Copland IB, Kavanagh BP, Engelberts D, McKerlie C, Belik J, Post M. Early changes in lung gene expression due to high tidal volume. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 168: 1051–1059, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Copland IB, Post M. Stretch-activated signaling pathways responsible for early response gene expression in fetal lung epithelial cells. J Cell Physiol 210: 133–143, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dranoff G, Crawford AD, Sadelain M, Ream B, Rashid A, Bronson RT, Dickersin GR, Bachurski CJ, Mark EL, Whitsett JA, Mulligan RC. Involvement of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in pulmonary homeostasis. Science 264: 713–716, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fanaroff AA, Stoll BJ, Wright LL, Carlo WA, Ehrenkranz RA, Stark AR, Bauer CR, Donovan EF, Korones SB, Laptook AR, Lemons JA, Oh W, Papile LA, Shankaran S, Stevenson DK, Tyson JE, Poole WK; NICHD Neonatal Network Trends in neonatal morbidity and mortality for very low birthweight infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol 196: 147.e141–147.e148, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Finer NN, Carlo WA, Walsh MC, Rich W, Gantz MG, Laptook AR, Yoder BA, Faix RG, Das A, Poole WK, Donovan EF, Newman NS, Ambalavanan N, Frantz ID, 3rd, Buchter S, Sánchez PJ, Kennedy KA, Laroia N, Poindexter BB, Cotten CM, Van Meurs KP, Duara S, Narendran V, Sood BG, O'Shea TM, Bell EF, Bhandari V, Watterberg KL, Higgins RD; SUPPORT Study Group of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver NICHD Neonatal Research Network Early CPAP versus surfactant in extremely preterm infants. N Engl J Med 362: 1970–1979, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hillman N, Kallapur SG, Pillow JJ, Polglase GR, Nitsos I, Ikegami M, Jobe AH. Inhibitors of inflammation and endogenous surfactant pool size as modulators of lung injury with initiation of ventilation in preterm sheep. Respir Res 11: 151, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hillman NH, Kallapur SG, Pillow JJ, Moss TJ, Polglase GR, Nitsos I, Jobe AH. Airway injury from initiating ventilation in preterm sheep. Pediatr Res 67: 60–65, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hillman NH, Kallapur SG, Pillow JJ, Moss TJ, Polglase GR, Nitsos I, Jobe AH. Airway injury from initiating ventilation in preterm sheep. Pediatr Res 67: 60–65, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hillman NH, Moss TJ, Kallapur SG, Bachurski C, Pillow JJ, Polglase GR, Nitsos I, Kramer BW, Jobe AH. Brief, large tidal volume ventilation initiates lung injury and a systemic response in fetal sheep. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 176: 575–581, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hillman NH, Pillow JJ, Ball MK, Polglase GR, Kallapur SG, Jobe AH. Antenatal and postnatal corticosteroid and resuscitation induced lung injury in preterm sheep. Respir Res 10: 124, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hooper SB, Kitchen MJ, Siew ML, Lewis RA, Fouras A, te Pas AB, Siu KK, Yagi N, Uesugi K, Wallace MJ. Imaging lung aeration and lung liquid clearance at birth using phase contrast X-ray imaging. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 36: 117–125, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Iwaki M, Ito S, Morioka M, Iwata S, Numaguchi Y, Ishii M, Kondo M, Kume H, Naruse K, Sokabe M, Hasegawa Y. Mechanical stretch enhances IL-8 production in pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 389: 531–536, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jobe A, Kramer BW, Moss TJ, Newnham J, Ikegami M. Decreased indicators of lung injury with continuous positive expiratory pressure in preterm lambs. Pediatr Res 52: 387–392, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jobe AH, Hillman N, Polglase G, Kramer BW, Kallapur S, Pillow J. Injury and inflammation from resuscitation of the preterm infant. Neonatology 94: 190–196, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jobe AH, Ikegami M. Biology of surfactant. Clin Perinatol 28: 655–669, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jobe AH, Newnham JP, Willet KE, Moss TJ, Ervin MG, Padbury JF, Sly PD, Ikegami M. Endotoxin induced lung maturation in preterm lambs is not mediated by cortisol. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 162: 1656–1661, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kallapur SG, Moss JTM, Newnham JP, Ikegami M, Jobe AH. Recruited inflammatory cells mediate endotoxin-induced lung maturation in preterm fetal lambs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 172: 1315–1321, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kallapur SG, Nitsos I, Moss TJ, Polglase GR, Pillow JJ, Cheah FC, Kramer BW, Newnham JP, Ikegami M, Jobe AH. IL-1 mediates pulmonary and systemic inflammatory responses to chorioamnionitis induced by LPS. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 179: 955–961, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kramer BW, Ikegami M, Moss TJ, Nitsos I, Newnham JP, Jobe AH. Endotoxin-induced chorioamnionitis modulates innate immunity of monocytes in preterm sheep. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 171: 73–77, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kramer BW, Jobe AH, Ikegami M. Monocyte function in preterm, term, and adult sheep. Pediatr Res 54: 52–57, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kramer BW, Joshi SN, Moss TJ, Newnham JP, Sindelar R, Jobe AH, Kallapur SG. Endotoxin-induced maturation of monocytes in preterm fetal sheep lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293: L345–L353, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kramer BW, Moss TJ, Willet KE, Newnham JP, Sly PD, Kallapur SG, Ikegami M, Jobe AH. Dose and time response after intraamniotic endotoxin in preterm lambs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164: 982–988, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 193: 265–275, 1951 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Morley CJ, Davis PG, Doyle LW, Brion LP, Hascoet JM, Carlin JB. Nasal CPAP or intubation at birth for very preterm infants. N Engl J Med 358: 700–708, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nardo L, Hooper SB, Harding R. Stimulation of lung growth by tracheal obstruction in fetal sheep: relation to luminal pressure and lung liquid volume. Pediatr Res 43: 184–190, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ngiam N, Peltekova V, Engelberts D, Otulakowski G, Post M, Kavanagh BP. Early growth response-1 worsens ventilator-induced lung injury by up-regulating prostanoid synthesis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 181: 947–956, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ngiam N, Post M, Kavanagh BP. Early growth response factor-1 in acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293: L1089–L1091, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. O'Reilly M, Hooper SB, Allison BJ, Flecknoe SJ, Snibson K, Harding R, Sozo F. Persistent bronchiolar remodeling following brief ventilation of the very immature ovine lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 297: L992–L1001, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Otto CM, Markstaller K, Kajikawa O, Karmrodt J, Syring RS, Pfeiffer B, Good VP, Frevert CW, Baumgardner JE. Spatial and temporal heterogeneity of ventilator-associated lung injury after surfactant depletion. J Appl Physiol 104: 1485–1494, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Resende JG, Menezes CG, Paula AM, Ferreira AC, Zaconeta CA, Silva CA, Rodrigues MP, Tavares P. Evaluation of peak inspiratory pressure and respiratory rate during ventilation of an infant lung model with a self-inflating bag. J Pediatr (Rio J) 82: 359–364, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sanchez-Esteban J, Wang Y, Gruppuso PA, Rubin LP. Mechanical stretch induces fetal type II cell differentiation via an epidermal growth factor receptor-extracellular-regulated protein kinase signaling pathway. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 30: 76–83, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schmölzer GM, Kamlin OC, O'Donnell CP, Dawson JA, Morley CJ, Davis PG. Assessment of tidal volume and gas leak during mask ventilation of preterm infants in the delivery room. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. In press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Shah TA, Hillman NH, Nitsos I, Polglase GR, Jane Pillow J, Newnham JP, Jobe AH, Kallapur SG. Pulmonary and systemic expression of monocyte chemotactic proteins in preterm sheep fetuses exposed to lipopolysaccharide-induced chorioamnionitis. Pediatr Res 68: 210–215, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. van Marter LJ, Pagano M, Allred EN, Levitorn A, Kuban KC. Rate of bronchopulmonary dysplasia as a function of neonatal intensive care practices. J Pediatr 120: 938–946, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Vlahakis NE, Schroeder MA, Limper AH, Hubmayr RD. Stretch induces cytokine release by alveolar epithelial cells in vitro. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 277: L167–L173, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wallace MJ, Probyn ME, Zahra VA, Crossley K, Cole TJ, Davis PG, Morley CJ, Hooper SB. Early biomarkers and potential mediators of ventilation-induced lung injury in very preterm lambs. Respir Res 10: 19, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wheeler DS, Wong HR. Heat shock response and acute lung injury. Free Radic Biol Med 42: 1–14, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]