Abstract

Cigarette smoke represents a major risk factor for the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a respiratory condition associated with airflow obstruction, mucus hypersecretion, chronic inflammation, and upregulation of inflammatory mediators such as the monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1). MCP-1 through its receptor CCR2 induces chemotaxis and activates 44/42MAPK, a kinase known to play a key role in mucin regulation in bronchial epithelium. In the present study we used differentiated primary cultures of normal human bronchial epithelial (NHBE) cells to test whether MCP-1 through its receptor CCR2 induces mucin upregulation. We have provided evidence that NHBE cells release MCP-1 to the epithelial surface and express the CCR2B isoform of the receptor mainly at the apical pole. In addition, we found that MCP-1 has a novel function in airway epithelium, increasing the two major airway mucins MUC5AC and MUC5B, an effect mediated, at least in part, by a cascade of events initiated by interaction of its receptor CCR2B with Gq subunits in caveolae, followed by PLCβ, PKC, and 44/42MAPK activation. We also have shown that MCP-1 is able to induce its own expression using the same receptor but through a different pathway that involves RhoA GTPase. Furthermore, we found that a single exposure to MCP-1 is enough to induce MCP-1 secretion and sustained mucin upregulation up to 7 days after initial exposure, an effect mediated by CCR2B as confirmed using short hairpin RNA. These results agree with our data in smoker's airway epithelium, where CCR2B is present in MUC5AC- and MUC5B-expressing cells and augmented MCP-1 expression is associated with increased MUC5AC and MUC5B immunolabeling, suggesting that the mechanisms described in primary cell cultures in the present study are operative in vivo. Therefore, therapeutic approaches targeting MCP-1/CCR2B may be useful in preventing not only influx of inflammatory cells to the airways but also mucus hypersecretion and goblet cell hyperplasia.

Keywords: monocyte chemotactic protein-1, cc chemokine receptor 2, mucin

cigarette smoke is a major risk factor for the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a respiratory condition associated with chronic inflammation and mucus hypersecretion (3, 40, 50). Airflow obstruction linked to increased mucin production (21) and augmented concentrations of proinflammatory mediators, including the monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), are observed in smokers (26). MCP-1 is also elevated in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), sputum, exhaled breath condensate samples, and bronchiolar epithelium from smokers and patients with COPD, and it has been correlated with increased recruitment of inflammatory cells to the airways (7, 12, 14, 16, 24, 26–28, 53).

MCP-1 is a CC chemokine, also known as chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2), that mediates its effects through the G protein coupled-receptor (GPCR) CCR2 (CC chemokine receptor 2), a protein that presents two variants, CCR2A and CCR2B (10). In addition to induce monocyte/macrophage, basophil, mast cell, and T cell migration (52), MCP-1 acts on resident cells within a tissue, triggering other cellular functions such as integrin activation, cytoprotection, and tight-junction opening through different signaling pathways including 44/42MAPK and RhoA GTPase (2, 6, 49, 51). We have previously shown, in primary cultures of normal human airways epithelial (NHBE) cells, that a long-lasting mucous phenotype with increased mucin expression induced by oxidative stress is mediated by 44/42MAPK (8, 9). Since 44/42MAPK plays a key role in regulating mucin expression/secretion (40) and it is activated by MCP-1 in other cells (6, 51), in the present study we assessed whether MCP-1 induces the expression of the two major airway mucins MUC5AC and MUC5B in NHBE cells. Although activation of 44/42MAPK by MCP-1 has been described previously, the molecular pathway downstream of CCR2B remain unclear (6, 51). Other GPCRs, such as the muscarinic receptor 3, utilizes Gq subunits, in concert with the diacylglycerol (DAG)/protein kinase C (PKC) arm of the phospholipase Cβ (PLCβ) signaling pathway to activate 44/42MAPK (5). Gq subunits are known to concentrate in caveolae and to interact with caveolin-1 (37), a protein that possesses a scaffolding domain to which signaling molecules such as Gq, PLCβ, PKC, and 44/42MAPK bind and start their corresponding signaling pathways (38, 44). Caveolin-1 is present in airway epithelium (25) and in 16HBE and 1HAEo- cells, both human airway epithelial cell lines (47). Interestingly, caveolin-1 knockdown suppresses MCP-1-induced chemotaxis in astrocytes (17), suggesting that caveolae are involved in MCP-1 responses. In the present study we used NHBE cells to assess MCP-1 and CCR2 mRNA and protein expression and to test the hypothesis that MCP-1 induces CCR2B/Gq recruitment in caveolae in concert with PLCβ and PKC that ultimately activates 44/42MAPK and induces MUC5AC and MUC5B. In addition, it has been reported that MCP-1 upregulates its own gene and protein expression through a long-lasting MCP1/CCR2-dependent amplification loop (4, 42). Therefore, since MCP-1 is secreted by airway epithelium (12, 31) and inflammatory cells (12, 15, 48), it is likely that an autocrine/paracrine control of MCP-1 takes place in the airway lumen, particularly when inflammatory cells are recruited. We presently report that a similar autocrine/paracrine loop triggered by MCP-1 was able to sustain a long-lasting mucous phenotype. These results were consistent with the immunolocalization and expression of MCP-1 and CCR2B as well as MUC5AC and MUC5B increases in airway epithelium from tissue sections obtained from smoker vs. nonsmoker donors, suggesting that the mechanisms described in NHBE cultures are operative in vivo.

METHODS

Additional details on reagents and methods are provided as Supplemental Data. (Supplemental data for this article is available online at the American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology website.)

Materials.

All materials were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise specified.

Primary cultures of NHBE cells at the air-liquid interface and tracheobronchial tissues.

Primary cultures of NHBE cells and tracheobronchial tissues were obtained from lung donors through the University of Miami Life Alliance Organ Recovery Agency with approval from the local Institutional Review Board, as previously reported (9, 35). Primary cultures of NHBE cells were obtained from normal lung donors. Briefly, passage 0 (P0) cells were expanded, and then P1 cells were redifferentiated in 24-mm Transwell clear culture inserts (Corning Costar, Cambridge, MA) coated with human placental collagen at 37°C in humidified air supplemented with 5% (vol/vol) CO2 (9, 35). The apical surface was exposed to the air as soon as the cells reached confluence. Cultures were used for experiments after reaching full differentiation (∼3 wk on air), as assessed by visual confirmation of beating cilia and mucus. Under these conditions, cultures had 89 ± 4% of ciliated cells (9).

Tracheobronchial tissues from 4 nonsmoker and 4 smoker lung donors (22–59 yr old, with less than 3 days of intubation) were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), and embedding and sectioning were performed by the Histology Laboratory at the University of Miami Hospital and Clinics, Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center. A smoker donor was defined by the following two criteria: 1) Centers for Disease Control (CDC): a person who had smoked at least 100 cigarettes or more and was currently a smoker either every day or some days (1) and 2) histological criteria: lungs with histological hallmarks of chronic bronchitis (enlargement of tracheobronchial submucosal glands, mucous cell metaplasia, and hyperplasia) (22). Smoker lung donors were compared with a control group of life-long nonsmokers.

Protocols.

Since EGF increases mucin expression (9), exogenous EGF was removed from culture medium 48 h before the studies. After treatments, apical washes, RNA, and proteins were collected and stored for further analysis. In experiments designed to test the effects of MCP-1 on MUC5AC, MUC5B, and MCP-1 mRNA and protein expression, NHBE cells from at least three different lung donors and in duplicate wells for each experimental condition were apically exposed to PBS or human recombinant MCP-1 (50 ng/ml, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Treatment was removed after 30 min, and then apical surfaces were rinsed with PBS to eliminate remnant exogenous MCP-1. In experiments aimed at determining the signaling pathways activated by MCP-1, replicate cultures from n ≥ 3 different lung donors were pretreated with inhibitors for CCR2B [RS102895, 0.1 mM, 30 min (33)], 44/42MAPK [U0126, 1 μM, 30 min (11)], caveolae integrity [methyl-β-cyclodextrin, 10 mM, 1 h (54) or filipin, 5 μg/ml, 1 h (19)], Gq signaling [GP antagonist-2A, 10 μM, 1 h; Enzo, Plymouth Meeting, PA (20)], PLCβ [U-73122, 1 μM, 30 min (34)], PKC [Myr-RFARKGALRQKNV, 50 μM, 30 min (13)], or RhoA GTPase [cell-permeable C3 exoenzyme, 1 μg/ml, 30 min; Cytoskeleton, Denver, CO (49)] at 37°C. The concentration of inhibitors used did not induce cytotoxicity in our cultures (see Supplemental Data for details and Supplemental Fig. S1). After pretreatment with the different inhibitors, MCP-1 was added apically to the cultures and cell lysates were collected after 10 min to assess phosphorylation of the target signaling molecules. To assess MCP-1, MUC5AC, and MUC5B mRNA expression, treatments were removed after 30 min and RNA was collected after 24 h. Since PBS plus individual inhibitors did not show statistical differences with PBS alone in any of the experiments referenced above, PBS was used as control. In experiments aimed at determining sustained MCP-1 and mucin expression, apical washes and cell lysates samples were collected after 7 days from the initial stimuli. In addition, replicate cultures were fixed with PFA 4% for immunofluorescence (IF).

Quantitative real-time PCR.

PCR amplification was performed using the iCycler IQ (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and a premade TaqMan gene expression array (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with TaqMan MGB probes, FAM-labeled assays including gene-specific primer, and probe sets designed against MCP-1 (Hs00234140_m1), MCP-2 (Hs00271615_m1), MCP-3 (Hs00171147_m1), MCP-4 (Hs00234646_m1), CCR2A (Hs00174150_m1), CCR2B (Hs00704702_s1), MUC5AC (Hs01365601_m1), MUC5B (Hs00861588_m1), or caveolin-1 (Hs00971716_m1). Samples were normalized using the housekeeping gene GAPDG (Hs99999905_m1). The comparative threshold cycle method (ΔΔCt) was used for relative quantization (30).

Immunoblotting.

Cell lysates were run on 4–15% Tris·HCl Ready Gels (Bio-Rad) under reducing conditions. Western blotting was performed using primary antibodies against CCR2B, phosphorylated 44/42MAPK, 44/42MAPK, β-actin, and caveolin-1. Membranes were developed, densitometry was performed using QuantityOne software (see Supplemental Data for details), and β-actin was used as a control for protein loading. Since 44/42MAPK-to-β-actin ratios did not change with MCP-1 treatment (Supplemental Fig. S2), 44/42MAPK activation was expressed as p44/42MAPK/β-actin.

Immunofluorescence.

Cells were labeled with specific antibodies against MUC5AC, MUC5B, MCP-1, CCR2B, acetylated tubulin, and caveolin-1 by IF. Corresponding nonimmune IgGs (mouse, rabbit, or goat) were used as negative controls. Methods for antigen retrieval varied slightly for each primary antibody (a full description of the IF protocols is provided in the Supplemental Data). Fluorescent images were obtained using the confocal laser scanning microscopes Zeiss LSM510 and LSM700 and the Axiovert 200M fluorescent microscope with the slider module Apotome (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Jena, Germany).

Quantitative analysis of MCP-1.

MCP-1 secreted into the apical compartment of NHBE cells (n = 8 different lung donors) was measured in apical washes by using a commercially available ELISA kit according to the manufacturer's guidelines (Quantikine kit; R&D Systems). Results are expressed as picograms in apical washes normalized to milligrams of cell protein.

CCR2B coimmunoprecipitation with caveolin-1 or Gq subunits.

Cells were lysed with a nonionic detergent (Nonidet P-40) to preserve protein association and incubated with Dynabeads (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) plus rabbit polyclonal anti-CCR2B antibody or nonimmune rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; both 5 μg/ml) following the manufacturer's instructions. Immunoprecipitates were examined for caveolin-1 by Western blotting using mouse anti-caveolin-1 (1 μg/ml; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) followed by alkaline phosphatase (AP)-conjugated anti-mouse antibodies (1,000 dilution; KPL, Gaithersburg, MD). The same membrane was stripped with Re-blot-plus (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and reprobed with mouse anti-Gq (1 μg/ml; BD Biosciences). Blot development and quantification were preformed as described in the Supplemental Data. Samples exposed to rabbit IgG did not show a positive signal for caveolin-1 or Gq subunits, indicating that our samples did not present nonspecific binding to rabbit IgGs (results not shown). In addition, when cell lysates were incubated with agarose-conjugated anti-caveolin-1 antibodies, CCR2B did not show differences compared with CCR2B coimmunoprecipitation (Supplemental Fig. S3 and Supplemental Data).

CCR2B knockdown.

CCR2B knockdown was achieved using short hairpin (sh)RNA lentiviruses. Details on reagents and methods are provided in Supplemental Data.

RhoA GTPase activity assay.

RhoA GTPase activity was measured in cell lysates collected from NHBE cultures using an ELISA-based RhoA Activation Assay Biochem kit (G-LISA; Cytoskeleton) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Equal amount of protein were loaded in each well.

MUC5AC and MUC5B ELISA.

Mucin's ELISA assays were performed as described (8, 9) using anti-MUC5AC (2 μg/ml; EMD, Gibbstown, NJ) or anti-MUC5B antibodies (2 μg/ml; Invitrogen). Results are expressed as relative changes above PBS. This was necessary because purified MUC5AC or MUC5B were not available to calibrate the assay.

Statistical analysis.

Data are means ± SE. Statistical significance between two groups was assessed using Student's t-test. Differences between multiple groups were compared using a one-way analysis of variance followed by the Tukey Kramer honestly significant difference test. The Levene test was used to analyze the homogeneity of variances. Significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

MCP-1 and CCR2B are expressed in human airway epithelial cells.

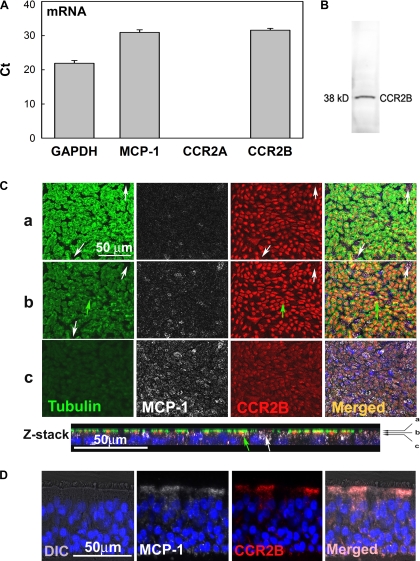

Basolateral MCP-1 secretion by NHBE cells has been reported previously (32). To confirm these results, mRNA and protein expression were assessed by quantitative PCR (qPCR), IF, and ELISA. We found that both MCP-1 mRNA and protein (Fig. 1, A and C) are present in NHBE cells. In addition, to investigate whether this chemokine is secreted into the apical compartment of NHBE cells, protein secretion was assessed in apical washes by ELISA. We found that 388 ± 128 pg/mg cell protein of MCP-1 were secreted in basal conditions (see Fig. 6), suggesting that epithelial MCP-1 contributes to the total pool of this chemokine reported in airway secretions. Afterward, to identify which CCR2 isoform is expressed by NHBE cells, CCR2A and CCR2B were assessed by qPCR. We found for the first time that CCR2B but not CCR2A mRNA is present in NHBE cells (Fig. 1A), results confirmed by Western blotting (Fig. 1B) and IF (Fig. 1C). Figure 1C shows that even though CCR2B is expressed mostly in ciliated cells (acetylated tubulin-positive cells; green arrows), this receptor is also present in other cell types (Fig. 1C, white arrows). To confirm that CCR2B is present in human airway epithelium, CCR2B expression was assessed by IF in tracheobronchial tissue sections. Figure 1D shows that, in agreement with findings in NHBE cells, CCR2B is expressed mainly at the apical pole of airway epithelium.

Fig. 1.

Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) and its receptor, CC chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2B), are expressed in airway epithelial cells. A: GAPDH, MCP-1, CCR2A, and CCR2B mRNA expression in normal human bronchial epithelial (NHBE) cells was assessed by quantitative PCR (qPCR) and expressed as threshold cycle (Ct). Bar graphs show means ± SE (n = 10 different lung donors). B: CCR2B protein expression was confirmed by Western blotting. C: in addition, NHBE cells were labeled for MCP-1 (white), CCR2B (red), and acetylated tubulin (green; ciliated cell marker) by immunofluorescence (IF) and analyzed using confocal fluorescence microscopy (×63 objective lens). Three x-y sections (a–c) are shown (top) and indicated with arrows in the Z-stack reconstruction (bottom). Green arrows show ciliated cells expressing CCR2B, whereas white arrows indicate nonciliated cells expressing CCR2B. D: MCP-1 (white) and CCR2B (red) localization in human tracheobronchial sections scanned using fluorescence microscopy (×40 objective lens). Nuclei were labeled with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole(DAPI). Differential interference contrast (DIC) images are also shown.

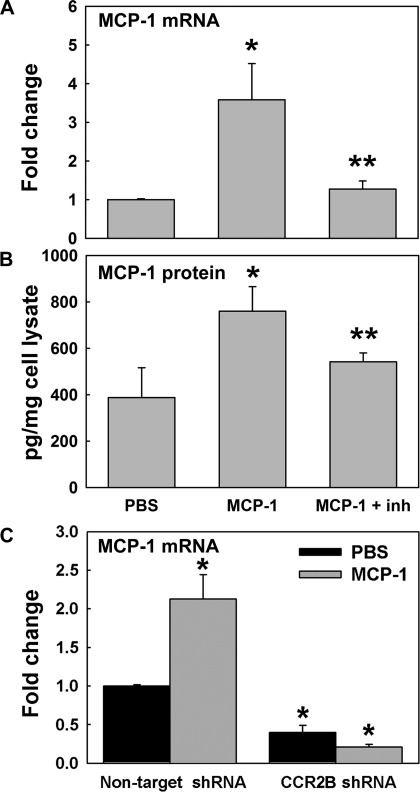

Fig. 6.

MCP-1 induces its own mRNA and protein expression through CCR2B. MCP-1 mRNA and protein expression were assessed in NHBE cells treated with PBS or MCP-1 by qPCR and ELISA at day 1 after initial treatment. Effect of a CCR2B inhibitor (inh; RS102895) was assessed at the mRNA (A) and protein (B) levels. *P < 0.05 vs. PBS. #P < 0.05 vs. MCP-1. C: MCP-1 mRNA expression in NHBE cells infected with nontarget or CCR2B short hairpin (sh)RNA expressing lentivirus and exposed to PBS or MCP-1. Bar graphs show means ± SE obtained from 3 different lung donors. *P < 0.05 vs. PBS nontarget shRNA.

Since other ligands besides MCP-1, such as MCP-2 (CCL8), MCP-3 (CCL7), and MCP-4 (CCL13), are also able to bind and signal through CCR2B (41), expression of these chemokines was also assessed by qPCR. We found that only MCP-3 was slightly expressed in some of the analyzed lungs (n = 10), and its expression did not change with MCP-1 treatment (data not shown). Therefore, MCP-3 was not further explored.

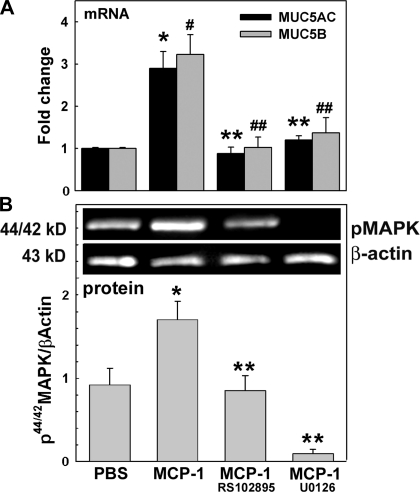

MCP-1 induces MUC5AC and MUC5B upregulation through CCR2B and 44/42MAPK.

To address the question of whether MCP-1 upregulates mucin expression, we assessed MUC5AC and MUC5B mRNA and protein by qPCR. Figure 2A shows that at day 1 after the initial stimuli, MCP-1 increased MUC5AC (2.9 ± 0.4- vs. 1.0 ± 0.1-fold change in PBS control, P < 0.01) and MUC5B (3.2 ± 0.5- vs. 1.0 ± 0.1-fold change in PBS control, P < 0.01) mRNA expression. Next, to test whether MUC5AC and MUC5B induction by MCP-1 was mediated by CCR2B, we exposed NHBE cells to PBS or MCP-1 in the presence or absence of the CCR2B inhibitor RS102895. Figure 2A shows that MCP-1-induced MUC5AC and MUC5B mRNA were blocked by the CCR2B inhibitor (0.9 ± 0.2- and 1.0 ± 0.2-fold change, respectively vs. MCP-1, P < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

MCP-1 induces mucin upregulation and 44/42MAPK activation through CCR2B. NHBE cells were exposed to apical PBS (control), MCP-1, or MCP-1 + RS102895 (CCR2B inhibitor) or U0126 [phosphorylated 44/42MAPK (p44/42MAPK) inhibitor]. A: samples (n = 5 different lung donors) were analyzed for MUC5AC and MUC5B mRNA expression by qPCR. Results are expressed as fold change vs. control. *P < 0.05 vs. MUC5AC in PBS. #P < 0.05 vs. MUC5B in PBS. **P < 0.05 vs. MUC5AC in MCP-1-treated cultures. ##P < 0.05 vs. MUC5B in MCP-1-treated cultures. B: p44/42MAPK and β-actin immunoblotting (top) and p44/42MAPK/β-actin (bottom). Blot images are representative of the results obtained in 3 lung donors. Bar graphs show means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. PBS (nontreated control). **P < 0.05 vs. MCP-1.

In addition, we assessed the role of 44/42MAPK activation in MCP-1-induced MUC5AC and MUC5B increases. Cells were exposed to PBS or MCP-1 in the presence or absence of a 44/42MAPK inhibitor as described in methods. We found that U0126 blocked MUC5AC (1.3 ± 0.4-fold change vs. MCP-1, P < 0.05) and MUC5B (1.4 ± 0.4-fold change vs. MCP-1, P < 0.05) mRNA expression (Fig. 2A) induced by MCP-1. To further test whether MCP-1 through CCR2B is able to activate 44/42MAPK, NHBE cells pretreated with CCR2B or 44/42MAPK inhibitors were exposed to MCP-1 or PBS and 44/42MAPK activation was assessed by Western blotting, and results are expressed as 44/42MAPK/β-actin. Figure 2B shows that MCP-1 induced 44/42MAPK activation (1.7 ± 0.2- vs. 1.0 ± 0.1-fold change in PBS control, P < 0.05), an effect inhibited by blocking CCR2B or 44/42MAPK (0.8 ± 0.4- and 0.1 ± 0.1-fold change, respectively; both P < 0.05 vs. MCP-1). Our observations strongly suggest that MCP-1-induced 44/42MAPK activation is involved in the control of MUC5AC and MUC5B expression through CCR2B.

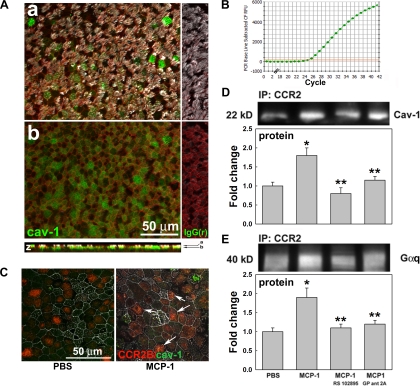

MCP-1 induces caveolin-1 interaction with CCR2B and Gq subunits.

Since caveolin-1 expression has been reported in tracheal epithelium (25) and human airway epithelial cell lines (47), we used qPCR and IF to test its mRNA and protein expression in primary cultures of NHBE cells. We found that caveolin-1 is expressed at the mRNA (Fig. 3B) and protein level, mostly at the apical pole of NHBE cells (Fig. 3A). To assess whether MCP-1 induces CCR2B/caveolin-1 interaction, NHBE cells were exposed to PBS or MCP-1 and colocalization was assessed by IF. Figure 3C shows that MCP-1 increased CCR2B/caveolin-1 colocalization in NHBE cells (white arrows). To confirm this interaction, we exposed cells apically to PBS or MCP-1 in the presence or absence of a specific CCR2B inhibitor. In addition, to further assess whether MCP-1 increases Gq interaction with CCR2B, we also used an inhibitor of Gq signaling (GP antagonist 2A). Protein interactions were quantified by coimmunoprecipitation of CCR2B with caveolin-1 or Gq subunits using an anti-CCR2B antibody followed by caveolin-1 or Gq immunoblotting and densitometry. Figure 3D shows that MCP-1 increased caveolin-1 pull-down by CCR2B (1.8 ± 0.2-fold change, P < 0.05 vs. 1.0 ± 0.1-fold change in PBS), an effect blocked using CCR2B or Gq inhibitors (0.8 ± 0.2- and 1.2 ± 0.1-fold change, respectively, P < 0.05 vs. MCP-1). The same result was observed for Gq subunit, where MCP-1 increased CCR2B/Gq interaction (Fig. 3E; 1.9 ± 0.3-fold change, P < 0.05 vs. 1.0 ± 0.1-fold change in PBS), an effect blocked by RS102895 or GP antagonist 2A (1.1 ± 0.1- and 1.2 ± 0.1-fold change, respectively, P < 0.05 vs. MCP-1). In addition, pull-down with anti-caveolin-1 antibodies also showed increased CCR2B induced by MCP-1 (Supplemental Fig. S3). Altogether these results indicate that MCP-1 induces CCR2B interaction with both caveolin-1 and Gq, suggesting that CCR2B signaling pathway is initiated in caveolae in conjunction with Gq subunits.

Fig. 3.

MCP-1 induces caveolin-1 (Cav-1) and Gq subunit interaction with CCR2B. A: Cav-1 protein was labeled in green, cellular cytoskeletal shape (F-actin) with phalloidin (red), and cilia with acetylated tubulin (white). Cells were scanned using confocal fluorescence microscopy (×63 objective lens); 2 x-y sections (a and b) are shown and indicated by arrows in the Z-reconstruction. B: Cav-1 mRNA expression. C: CCR2B (red)/Cav-1 (green) interaction in NHBE cells treated with PBS or MCP-1 was assessed by confocal microscopy using a ×63 objective lens, and colocalization is indicated (white arrows). D: CCR2B/Cav-1 interaction was quantified by coimmunoprecipitation, immunoprecipitation (IP), and Western blotting. E: CCR2B/Gq subunit interaction was tested by Gq pull-down using anti-CCR2B antibodies. Blot images are representative of the results obtained in 3 lung donors. Bar graphs show means ± SE obtained from 3 different lung donors. *P < 0.05 vs. PBS (nontreated control). **P < 0.05 vs. MCP-1.

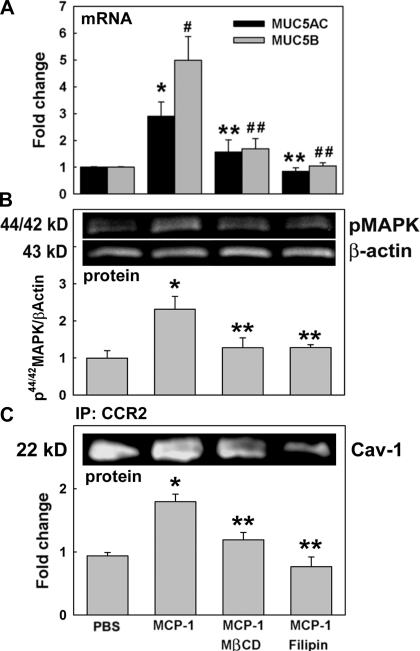

MCP-1-induced MUC5AC and MUC5B upregulation, 44/42MAPK activation, and CCR2B/caveolin-1 interaction in human airway epithelial cells are dependent on caveolae integrity.

We hypothesized that mucin increases and 44/42MAPK activation are mediated by CCR2B/Gq recruitment in caveolae when cells are exposed to MCP-1. Therefore, to first test whether caveolae disruption modifies MCP-1-induced mucin upregulation, NHBE cells were exposed to PBS or MCP-1 in the presence or absence of the caveolae disruptors methy-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) or filipin. MUC5AC and MUC5B mRNA expression was assessed by qPCR. Since MβCD and filipin did not change basal mucin mRNA expression, PBS-treated cells were used as control. Figure 4A shows that MCP-1-induced MUC5AC and MUC5B mRNA expression (2.9 ± 0.5- and 4.9 ± 1.4-fold change, respectively, vs. control, P < 0.05) was prevented when NHBE cells were pretreated with MβCD (1.5 ± 0.5- and 1.7 ± 0.3-fold change, both P < 0.05 vs. MCP-1) or filipin (0.9 ± 0.1- and 1.0 ± 0.1-fold change, both P < 0.05 vs. MCP-1). To test whether MCP-1-induced 44/42MAPK activation depends on caveolae integrity, NHBE cells were exposed to PBS or MCP-1 in the presence or absence of MβCD or filipin, as described above, and kinase activation was assessed by Western blotting. Figure 4B shows that MCP-1-induced 44/42MAPK phosphorylation (2.3 ± 0.4- vs. 1.0 ± 0.2-fold change in PBS, P < 0.05) was blocked with MβCD and filipin (1.3 ± 0.3- and 1.3 ± 0.1-fold change, respectively, both P < 0.05 vs. MCP-1). In addition, Fig. 4C shows that MCP-1-induced CCR2B/caveolin-1 interaction (1.8 ± 0.2-fold change, P < 0.05 vs. PBS control) was also prevented with MβCD or filipin (1.2 ± 0.1 and 0.8 ± 0.2, respectively, both P < 0.05 vs. MCP-1). These results provide evidence that intact caveolae are required for MCP-1-induced CCR2B/caveolin-1 interaction, 44/42MAPK activation, and MUC5AC and MUC5B upregulation.

Fig. 4.

MCP-1-induced mucin upregulation depends on 44/42MAPK activation and requires caveolae integrity. Cells were exposed to apical PBS (control) or MCP-1 in the presence or the absence of the caveolae disruptors methy-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) or filipin. A: samples (n = 4 different lung donors) were analyzed for MUC5AC and MUC5B mRNA expression by qPCR. Results are expressed as fold change vs. controls. *P < 0.05 vs. MUC5AC control. #P < 0.05 vs. MUC5B control. **P < 0.05, MUC5AC vs. MCP-1. ##P < 0.05, MUC5B vs. MCP-1. B: 44/42MAPK phosphorylation was assessed by Western blotting: p44/42MAPK and β-actin immunoblotting (top) and p44/42MAPK/β-actin (bottom). *P < 0.05 vs. PBS. **P < 0.05 vs. MCP-1. C: CCR2B/Cav-1 interaction was evaluated using coimmunoprecipitation and Cav-1 immunoblotting (top) and expressed as fold change of Cav-1 pulled down by anti-CCR2B antibody vs. control (bottom). Blot images are representative of the results obtained in 3 lung donors. Bar graphs show means ± SE obtained from 3 different lung donors. *P < 0.05 vs. PBS. **P < 0.05 vs. MCP-1.

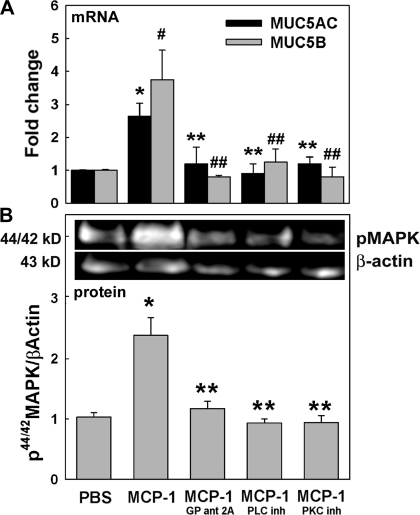

Gq/PLCβ/PKC mediate MCP-1-induced MUC5AC and MUC5B upregulation and 44/42MAPK activation in NHBE cells.

After confirming CCR2B/Gq interaction, we tested whether PLCβ and PKC were involved in MCP-1-induced mucin and 44/42MAPK activation in NHBE cells exposed to PBS or MCP-1 and in the presence or the absence of Gq, PLCβ, or PKC inhibitors. MUC5AC and MUC5B mRNA expression and 44/42MAPK activation were assessed by qPCR and Western blotting, respectively. Mucin expression and 44/42MAPK phosphorylation in cells treated only with inhibitors was not different from control cells (PBS) (results not shown); therefore, PBS-treated cells were used as controls. Figure 5A shows that MCP-1-induced MUC5AC and MUC5B (2.6 ± 0.1- and 3.8 ± 0.9-fold change, respectively, vs. PBS corresponding control, P < 0.05) was reduced by blocking Gq-dependent signaling (1.2 ± 0.6- and 0.8 ± 0.1-fold change, respectively; all P < 0.05 vs. MCP-1). Accordingly, when PLCβ inhibitor was used, the MCP-1 effect was also blocked (0.9 ± 0.3-fold change for MUC5AC and 1.2 ± 0.5-fold change for MUC5B, both P < 0.05 vs. their corresponding MCP-1). The same result was observed using a PKC inhibitor (1.2 ± 0.2- and 0.8 ± 0.3-fold change, respectively; both P < 0.05 vs. their corresponding MCP-1 levels). To further study whether Gq subunits, PLCβ, and PKC are involved in MCP-1-induced 44/42MAPK activation, NHBE cells pretreated with PBS, Gq, PLCβ, or PKC inhibitors were exposed to MCP-1. Figure 5B shows that MCP-1-induced 44/42MAPK activation (2.3 ± 0.6-fold change; P < 0.05 vs. 1.0 ± 0.2-fold change in PBS) was inhibited by blocking Gq, PLCβ, or PKC (1.2 ± 0.2-, 0.9 ± 0.1-, and 0.9 ± 0.2-fold change, respectively; all P < 0.05 vs. MCP-1). In summary, our observations strongly suggest that Gq subunits, PLCβ, and PKC are involved in MCP-1-induced 44/42MAPK activation that ultimately controls MUC5AC and MUC5B expression.

Fig. 5.

MCP-1-induced mucin upregulation and 44/42MAPK activation is dependent on Gq subunits, PLCβ, and PKC. Cells were exposed to apical PBS (control) or MCP-1 in the presence or absence of Gq (GP ant 2A), PLCβ, or PKC inhibitors. A: samples (n = 4 different lung donors) were analyzed for MUC5AC and MUC5B mRNA expression by qPCR. Results are expressed as fold change vs. the corresponding basal control. *P < 0.05 vs. MUC5AC control (PBS). #P < 0.05 vs. MUC5B control (PBS). **P < 0.05 vs. MCP-1-induced MUC5AC. ##P < 0.05 vs. MCP-1-induced MUC5B. B: p44/42MAPK and β-actin immunoblotting (top) and p44/42MAPK/β-actin (bottom). Blot images are representative of the results obtained in 3 lung donors. Bar graphs show means ± SE obtained from 3 different lung donors. *P < 0.05 vs. PBS. **P < 0.05 vs. MCP-1.

MCP-1 induces its own mRNA and protein expression through CCR2B.

To test whether MCP-1 increases its own expression and whether this effect is mediated by CCR2B, NHBE were exposed to MCP-1 in the presence or the absence of a CCR2B inhibitor. Figure 6A shows that MCP-1 increased its own mRNA expression (4.2 ± 1.1- vs. 1.0 ± 0.1-fold change in PBS control, P < 0.01) and that this effect was blocked by CCR2B inhibitor (1.2 ± 0.2-fold change, P < 0.05 vs. MCP-1). The same result was observed at the protein level (Fig. 6B), where MCP-1 increased its apical secretion (858 ± 84 vs. 388 ± 85 pg/mg cell lysate protein in control, P < 0.05), an effect reduced by blocking CCR2B (566 ± 75 pg/mg, P < 0.05). To confirm whether MCP-1-induced MCP-1 upregulation was mediated by CCR2B, we inhibited its mRNA translation using shRNA. Nontargeted (NT) shRNA was used as a nonsilencing RNA control. As shown in Supplemental Fig. S4A, infection of NHBE cells with CCR2B shRNA expressing lentivirus blocked CCR2B mRNA (0.4 ± 0.2- vs. 1.0 ± 0.1-fold change in NT shRNA, P < 0.05, n = 3 different lung donors). This effect was confirmed at the protein level by IF (Supplemental Fig. S4B). After that, NHBE cells infected with NT or CCR2B shRNA-lentivirus were exposed to PBS or MCP-1, as described above. Figure 6C shows that MCP-1 increased its own mRNA expression in NT shRNA control cells (2.1 ± 0.3-fold change vs. PBS, P < 0.05), whereas CCR2B shRNA not only blocked MCP-1-induced MCP-1 mRNA expression (0.2 ± 0.1- vs. 0.4 ± 01-fold change in PBS) but also decreased MCP-1 baseline levels (P < 0.05 vs. PBS in nontarget shRNA). These results suggest that CCR2B regulates basal and MCP-1-induced MCP-1 expression.

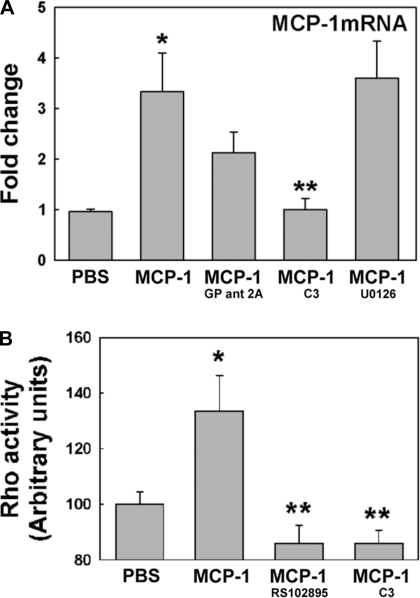

MCP-1 induces MCP-1 mRNA through RhoA GTPase activation.

To test whether Gq subunits participate in MCP-1-induced MCP-1 upregulation, NHBE cells were exposed to PBS or MCP-1 in the presence or absence of GP antagonist-2A as described previously. At day 1 after the initial stimuli, RNA was collected and MCP-1 mRNA expression was assessed by qPCR. We found that MCP-1 was induced in NHBE cells treated with MCP-1 (Fig. 7A; 3.3 ± 0.7- vs. 1.0 ± 0.1-fold change in PBS control, P < 0.01). Although Gq inhibitor decreased MCP-1 self-induced mRNA expression, this effect was not statistically significant (2.1 ± 0.5-fold change). Furthermore, 44/42MAPK inhibitor (U0126) was not able to inhibit the MCP-1 effect either (3.6 ± 0.7-fold change). This result suggests that MCP-1/CCR2B upregulation loop might be mediated by a different pathway independent of Gq subunit and 44/42MAPK. Other Gα proteins such as G12,13 subunits activate small GTPases such as RhoA GTPase as downstream effectors (43). Since MCP-1 has also mediated its effects through RhoA GTPase in endothelium (49), NHBE cells were exposed to PBS or MCP1 in the presence or the absence of C3 exoenzyme (to specifically inhibit the activity of RhoA GTPase) and MCP-1 mRNA was assessed by qPCR. Figure 7A shows that C3 exoenzyme reversed the MCP-1 effect, decreasing its mRNA expression to basal levels (1.0 ± 0.2-fold change, P < 0.05 vs. MCP-1). These results indicate the MCP-1 upregulated its own mRNA through CCR2B but using a different signaling pathway than the one activated for mucin increases, i.e., G12,13/RhoA GTPase instead of Gq/44/42MAPK. In addition, to confirm that MCP-1 is able to induce RhoA GTPase activation, NHBE cells with CCR2B inhibitor or C3 exoenzyme were used. RhoA GTPase activity was measured in cell lysates using an ELISA-based RhoA Activation Assay Biochem Kit. Results are expressed in arbitrary units (AU), and basal levels (PBS control) were considered as 100%. Figure 7B shows that MCP-1 induces RhoA GTPase activation (136 ± 11 vs. 100 ± 4 AU in PBS, P < 0.05), an effect mediated by CCR2B since its inhibitor reduced RhoA GTPase activity below baseline levels (86 ± 6 AU, P < 0.05 vs. MCP-1). MCP-1-induced RhoA GTPase activity was also blocked using the RhoA inhibitor (86 ± 5 AU, P < 0.05 vs. MCP-1). These results confirm previous results indicating that RhoA GTPase is a downstream effector for MCP-1/CCR2B-mediated effects.

Fig. 7.

MCP-1 induces its own mRNA expression through RhoA GTPase activation. A: NHBE cultures exposed to PBS or MCP-1 in the presence or absence of inhibitors for Gq signaling (GP ant 2A), RhoA GTPase activation (C3), or 44/42MAPK activation (U0120) were analyzed for MCP-1 mRNA expression by qPCR. B: in addition, PBS- or MCP-1-treated NHBE cells in the presence or absence of CCR2B (RS102895) or RhoA inhibitors (C3) were assessed for RhoA activation using an ELISA-like assay. Bar graphs show means ± SE obtained from 4 different lung donors. *P < 0.01 vs. PBS. **P < 0.05 vs. MCP-1.

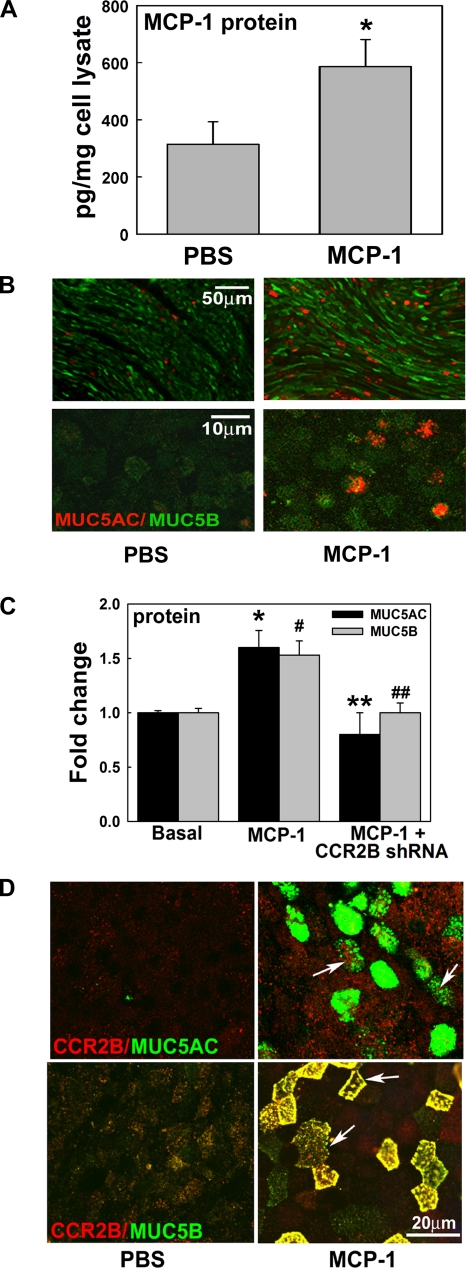

MCP-1/CCR2B autocrine/paracrine loop sustains MCP-1, MUC5AC, and MUC5B expression in NHBE cells.

Since MCP-1 induced its own upregulation, we assessed whether this effect can be sustained up to 7 days from the time of initial stimuli. Figure 8A shows that MCP-1 increased its own secretion (586 ± 73 vs. 314 ± 78 pg/mg in PBS), suggesting that MCP-1 produced by airway epithelium or other sources maintains the high levels of MCP-1 observed in BAL and sputum from smokers and COPD patients. To test whether MUC5AC and MUC5B remain increased 7 days after MCP-1 exposure, we assessed these mucins by using IF. We found that MCP-1 increased MUC5AC- and MUC5B-positive cells (Fig. 8B). To confirm these results and to test whether CCR2B was involved in this process, NHBE cells infected with NT or CCR2B shRNA expressing lentivirus were exposed to PBS or MCP-1, as described previously, and protein content was assessed at day 7 by ELISA. Figure 8C shows that MCP-1-increased MUC5AC (1.6 ± 0.2-fold change, P < 0.05 vs. 1.0 ± 0.1-fold change in basal control) and MUC5B expression (1.5 ± 0.1-fold change, P < 0.05 vs. 1.0 ± 0.1-fold change in basal control) was inhibited when CCR2B was knocked down (MUC5AC: 0.8 ± 0.2-fold change and MUC5B: 1.0 ± 0.1-fold change, both P < 0.05 vs. MCP-1). These data show that MCP-1 upregulates MUC5AC and MUC5B expression in the short term and also sustains mucin increases for at least 7 days, suggesting that a long-term effect is triggered by MCP-1 and CCR2B in these conditions. In addition, to test whether CCR2B is present in MCP-1-induced MUC5AC- or MUC5B-expressing cells, we assessed CCR2B, MUC5AC, and MUC5B protein expression in NHBE cells exposed to MCP-1. Figure 8D shows that CCR2B is present in MUC5AC- and MUC5B-positive cells (white arrows) induced by MCP-1. These results together with the lack of effect of MCP-1 in CCR2 shRNA cells in upregulating MUC5AC and MUC5B suggest that CCR2B is the key receptor in MCP-1-induced mucin regulation.

Fig. 8.

Sustained MUC5AC and MUC5B upregulation is dependent on MCP-1 and CCR2B. A: NHBE cultures exposed to PBS or MCP-1 were assessed for MCP-1 by ELISA. Bar graphs show means ± SE obtained from 4 different lung donors. *P < 0.05 vs. basal MCP-1. B: NHBE cells were also assessed for MUC5AC (red) and MUC5B (green) protein expression by IF at day 7 from the initial stimuli. Cultures were analyzed using fluorescence microscopy with ×10 (top images) or ×63 objective lenses (bottom images). C: anti-CCR2B shRNA blocked MCP-1-induced MUC5AC and MUC5B protein. Bar graphs show means ± SE from 3 different lung donors. *P < 0.05, MCP-1-induced MUC5AC vs. baseline. #P < 0.05, MCP-1-induced MUC5B vs. baseline. **P < 0.05, CCR2B-blocked MCP-1-induced MUC5AC vs. baseline. ##P < 0.05, CCR2B-blocked MCP-1-induced MUC5B vs. baseline. D: CCR2B immunolabeling (red) with MUC5AC (left, green) or MUC5B (right, green) in NHBE cells exposed to PBS or MCP-1.

Increased MUC5AC and MUC5B is associated with augmented MCP-1 in smokers' airways.

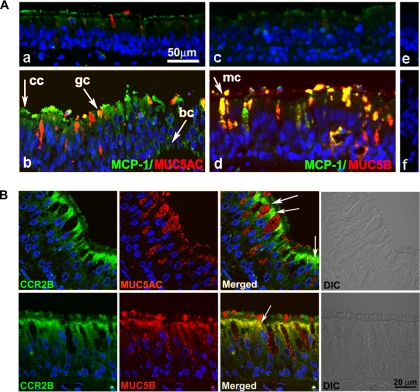

To assess whether the increased expression of mucins observed in smokers correlates with MCP-1 upregulation, we assessed MCP-1, MUC5AC, and MUC5B protein expression in tracheobronchial tissues obtained from nonsmoker and smoker lung donors. Comparison between tissue sections from nonsmoker (Fig. 9, Aa and Ac) and smoker donors revealed that smokers present MUC5AC (Fig. 9Ab) and MUC5B upregulation (Fig. 9Ad) accompanied by increased MCP-1 localized mostly at the ciliary border of airway epithelium but also present in mucous cells expressing MUC5AC or MUC5B, ciliated cells, and basal cells. These results together with our results in vitro point toward MCP-1 as an additional player in the intricate regulation of mucin expression in airway epithelium.

Fig. 9.

Increased MUC5AC and MUC5B are associated to MCP-1 and CCR2B. A: human tracheobronchial sections from a nonsmoker donor (a, c, e) and 2 smoker donors (b, d, f) were double-labeled with anti-MUC5AC (a and b; red) or anti-MUC5B (c and d; red) and anti-MCP-1 (a–d; green). Nonimmune IgGs are depicted in e and f. Arrows indicate ciliated (cc), goblet (gc), MUC5B-positive (mc), and basal cells (bc). B: human tracheobronchial sections from smoker donors were also labeled with CCR2B (green) and MUC5AC (top; red) or MUC5B (bottom; red). Nuclei were labeled with DAPI. Slides were scanned using confocal microscopy (×63 objective lens). Images represent variability of 8 different lung donors.

CCR2B is present in MUC5AC- and MUC5B-expressing cells from smokers' airways.

To confirm our results in vitro showing that CCR2B is present in MUC5AC- or MUC5B-expressing cells, we assessed CCR2B, MUC5AC, and MUC5B protein expression in tracheobronchial tissues obtained from smoker lung donors. We found that CCR2B occupies the apical compartment on ciliated cells but is limited to apical membrane cells expressing MUC5AC or MUC5B (Fig. 9B, white arrows), probably excluded by mucin granules. These results together with the in vitro data suggest that cells expressing CCR2B are targets for MCP-1-induced mucin expression in airway epithelium.

DISCUSSION

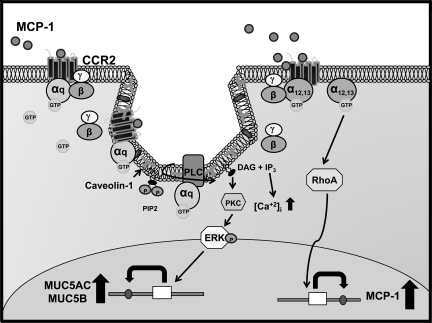

In the present report we provide evidence that MCP-1 has a novel function in airway epithelium of inducing MUC5AC and MUC5B mRNA and protein expression, an effect mediated, at least in part, by a cascade of events initiated by CCR2B/Gq interaction in caveolae followed by PLCβ, PKC, and 44/42MAPK activation (Fig. 10). We also found that MCP-1 through CCR2B-mediated RhoA GTPase activation induces its own expression, suggesting that sustained MCP-1 levels are involved with the mucin upregulation characteristic of airway inflammatory conditions. These results agree with our in vivo data, which show that augmented mucin expression is associated with increased MCP-1 and that CCR2B is present in MUC5AC- and MUC5B-expressing cell from smoker's airway epithelium.

Fig. 10.

Schematic of CCR2B signal transduction pathways that regulate MUC5AC, MUC5B, and MCP-1 expression. MCP-1 induces CCR2B/Gq interaction in caveolae. GTP-bound Gq-protein's effector interaction domain is exposed and activates PLCβ, which promotes phosphoinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) hydrolysis into 1,2-diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3). DAG promotes PKC activation. Activated PKC phosphorylates 44/42MAPK, which upregulates MUC5AC and MUC5B. In addition, MCP-1 also induces CCR2B/G12/13 interaction associated with increased RhoA GTPase activity and upregulation of MCP-1.

Although MCP-1 release by NHBE cells to the basolateral media (32) and CCR2 expression in BEAS-2B cells (31) have been reported previously, we found that MCP-1 is also secreted into the apical compartment and that only the CCR2B isoform is expressed in NHBE cells. CCR2B apical localization, confirmed in tracheobronchial tissue sections, suggests that in addition to the known chemotactic effects (12), MCP-1 can directly influence epithelial function. Accordingly, we found that MCP-1 upregulated MUC5AC and MUC5B levels through CCR2B, an effect that was confirmed using a receptor inhibitor and shRNA. Another significant finding in this study was the signaling pathway exerted by MCP-1/CCR2B on mucin expression. The present study showed that caveolin-1 and CCR2B are localized mainly at the apical pole of NHBE cells and that MCP-1 increases CCR2B/caveolin-1 interaction, 44/42MAPK activation, and MUC5AC and MUC5B upregulation, effects blocked by disrupting caveolae with MβCD or filipin. Although caveolin-1 involvement in MCP-1 chemotactic function has been described in astrocytes and endothelial cells (17, 18), its downstream molecular pathway remains unclear. We found that MCP-1 induces CCR2B/Gq interaction, which agrees with the report from Shi et al. (45), which demonstrates that Gq-deficient monocytes and dendritic cells had defective chemotactic responses upon MCP-1 stimulation. Using specific inhibitors, we also demonstrated that Gq, PLCβ, and PKC are indeed upstream mediators of MCP-1-triggered 44/42MAPK activation and MUC5AC and MUC5B upregulation. MCP-1-mediated effects through PLC and PKC have been described in neurons and the human eosinophilic leukemia cell line EoL-1 (29, 39), but they were not related to 44/42MAPK signaling. Therefore, our results show a novel integrated pathway induced by MCP-1 that includes CCR2/Gq interaction in caveolae, PLCβ, PKC, and 44/42MAPK activation that ultimately upregulates mucin expression, suggesting that MCP-1 belongs to the growing list of inflammatory mediators that induce mucin production and goblet cell hyperplasia through 44/42MAPK (40).

In this study, we also found that MCP-1 induces its own mRNA and protein expression, an effect mediated by CCR2B and RhoA GTPase, a pathway that mediates the increased permeability in mouse brain endothelial cells (49) and MCP-1 expression induced by lysophosphatidic acid in endothelial cells (46). In addition, cells infected with CCR2B shRNA lentivirus showed decreased MCP-1 basal mRNA levels, indicating that the basal expression of this chemokine is likely regulated by a MCP-1/CCR2B-dependent loop. We also found that a single exposure to MCP-1 was enough to induce increased MCP-1 secretion and sustained mucin upregulation up to 7 days after initial treatment, an effect blocked by CCR2B shRNA. Furthermore, we showed for the first time that MCP-1 increases occur with MUC5AC and MUC5B upregulation in smokers' airways and that CCR2B is present in MUC5AC- and MUC5B-expressing cells. These results are in agreement with previous studies that showed augmented MCP-1 mRNA in bronchial tissue (16) and protein levels in BAL, sputum, and exhaled breath condensate from smokers and COPD patients (7, 24, 26, 53), conditions often associated with increased MUC5AC and MUC5B expression (8, 23, 36). These results suggest that MCP-1 secreted to the airways lumen by airway epithelium (12, 31) and other sources, such as inflammatory cells (12, 15, 48), can promote an autocrine/paracrine control of MCP-1 by epithelial cells and likely contributes to the increased MCP-1 levels reported in airway secretion from smokers and COPD patients (7, 12, 24, 26, 53).

The mechanisms responsible for the regulation of mucin expression are complex and engage a number the mediators that involve different biochemical and cellular pathways/events. In the present report we provide evidence that MCP-1 has a novel function in airway epithelium: inducing MUC5AC and MUC5B upregulation. Therefore, therapeutic approaches targeting MCP-1/CCR2B may be useful in preventing not only inflammatory cell influx to the airways but also mucus hypersecretion and goblet cell hyperplasia characteristic of several respiratory diseases.

GRANTS

This work was supported by James and Esther King Biomedical Research Grant 07KN-02-12324 (S. M. Casalino-Matsuda), American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant 635093N (S. M. Casalino-Matsuda), the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute (M. E. Monzon), and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL073156 (R. M. Forteza).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. Gregory Conner, Nevis Fregien, and Matthias Salathe for support. We also thank Gabriel Gaidosh and the Adrienne Arsht Retinal Degeneration Research Laboratory, the Analytical Imaging Core, the Life Alliance Organ Recovery Agency, and the Histology Laboratory from Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center, all at the University of Miami.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 1992, and changes in the definition of current cigarette smoking. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 43: 342–346, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ashida N, Arai H, Yamasaki M, Kita T. Distinct signaling pathways for MCP-1-dependent integrin activation and chemotaxis. J Biol Chem 276: 16555–16560, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barnes PJ. New concepts in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Annu Rev Med 54: 113–129, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Belperio JA, Keane MP, Burdick MD, Lynch JP, 3rd, Xue YY, Berlin A, Ross DJ, Kunkel SL, Charo IF, Strieter RM. Critical role for the chemokine MCP-1/CCR2 in the pathogenesis of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. J Clin Invest 108: 547–556, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Budd DC, Willars GB, McDonald JE, Tobin AB. Phosphorylation of the Gq/11-coupled m3-muscarinic receptor is involved in receptor activation of the ERK-1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. J Biol Chem 276: 4581–4587, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cambien B, Pomeranz M, Millet MA, Rossi B, Schmid-Alliana A. Signal transduction involved in MCP-1-mediated monocytic transendothelial migration. Blood 97: 359–366, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Capelli A, Di Stefano A, Gnemmi I, Balbo P, Cerutti CG, Balbi B, Lusuardi M, Donner CF. Increased MCP-1 and MIP-1beta in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of chronic bronchitics. Eur Respir J 14: 160–165, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Casalino-Matsuda SM, Monzon ME, Day AJ, Forteza RM. Hyaluronan fragments/CD44 mediate oxidative stress-induced MUC5B up-regulation in airway epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 40: 277–285, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Casalino-Matsuda SM, Monzon ME, Forteza RM. Epidermal growth factor receptor activation by epidermal growth factor mediates oxidant-induced goblet cell metaplasia in human airway epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 34: 581–591, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Charo IF, Myers SJ, Herman A, Franci C, Connolly AJ, Coughlin SR. Molecular cloning and functional expression of two monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 receptors reveals alternative splicing of the carboxyl-terminal tails. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 2752–2756, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen Y, Thai P, Zhao YH, Ho YS, DeSouza MM, Wu R. Stimulation of airway mucin gene expression by interleukin (IL)-17 through IL-6 paracrine/autocrine loop. J Biol Chem 278: 17036–17043, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Boer WI, Sont JK, van Schadewijk A, Stolk J, van Krieken JH, Hiemstra PS. Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1, interleukin 8, and chronic airways inflammation in COPD. J Pathol 190: 619–626, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eichholtz T, de Bont DB, de Widt J, Liskamp RM, Ploegh HL. A myristoylated pseudosubstrate peptide, a novel protein kinase C inhibitor. J Biol Chem 268: 1982–1986, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Eickmeier O, Huebner M, Herrmann E, Zissler U, Rosewich M, Baer PC, Buhl R, Schmitt-Grohe S, Zielen S, Schubert R. Sputum biomarker profiles in cystic fibrosis (CF) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and association between pulmonary function. Cytokine 50: 152–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Frade JM, Mellado M, del Real G, Gutierrez-Ramos JC, Lind P, Martinez AC. Characterization of the CCR2 chemokine receptor: functional CCR2 receptor expression in B cells. J Immunol 159: 5576–5584, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fuke S, Betsuyaku T, Nasuhara Y, Morikawa T, Katoh H, Nishimura M. Chemokines in bronchiolar epithelium in the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 31: 405–412, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ge S, Pachter JS. Caveolin-1 knockdown by small interfering RNA suppresses responses to the chemokine monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 by human astrocytes. J Biol Chem 279: 6688–6695, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ge S, Song L, Serwanski DR, Kuziel WA, Pachter JS. Transcellular transport of CCL2 across brain microvascular endothelial cells. J Neurochem 104: 1219–1232, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hua H, Munk S, Whiteside CI. Endothelin-1 activates mesangial cell ERK1/2 via EGF-receptor transactivation and caveolin-1 interaction. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 284: F303–F312, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hunt RA, Bhat GJ, Baker KM. Angiotensin II-stimulated induction of sis-inducing factor is mediated by pertussis toxin-insensitive Gq proteins in cardiac myocytes. Hypertension 34: 603–608, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Innes AL, Woodruff PG, Ferrando RE, Donnelly S, Dolganov GM, Lazarus SC, Fahy JV. Epithelial mucin stores are increased in the large airways of smokers with airflow obstruction. Chest 130: 1102–1108, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jeffery PK. Histological features of the airways in asthma and COPD. Respiration 59, Suppl 1: 13–16, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kirkham S, Kolsum U, Rousseau K, Singh D, Vestbo J, Thornton DJ. MUC5B is the major mucin in the gel phase of sputum in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 178: 1033–1039, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ko FW, Lau CY, Leung TF, Wong GW, Lam CW, Hui DS. Exhaled breath condensate levels of 8-isoprostane, growth related oncogene alpha and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med 100: 630–638, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Krasteva G, Pfeil U, Drab M, Kummer W, Konig P. Caveolin-1 and -2 in airway epithelium: expression and in situ association as detected by FRET-CLSM. Respir Res 7: 108, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kuschner WG, D'Alessandro A, Wong H, Blanc PD. Dose-dependent cigarette smoking-related inflammatory responses in healthy adults. Eur Respir J 9: 1989–1994, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lai H, Rogers DF. New pharmacotherapy for airway mucus hypersecretion in asthma and COPD: targeting intracellular signaling pathways. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv 23: 219–231, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lee JS, Rosengart MR, Kondragunta V, Zhang Y, McMurray J, Branch RA, Choi AM, Sciurba FC. Inverse association of plasma IL-13 and inflammatory chemokines with lung function impairment in stable COPD: a cross-sectional cohort study. Respir Res 8: 64, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee JS, Yang EJ, Kim IS. The roles of MCP-1 and protein kinase C delta activation in human eosinophilic leukemia EoL-1 cells. Cytokine 48: 186–195, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−ΔΔCT) method. Methods 25: 402–408, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lundien MC, Mohammed KA, Nasreen N, Tepper RS, Hardwick JA, Sanders KL, Van Horn RD, Antony VB. Induction of MCP-1 expression in airway epithelial cells: role of CCR2 receptor in airway epithelial injury. J Clin Immunol 22: 144–152, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Malavia NK, Raub CB, Mahon SB, Brenner M, Panettieri RA, Jr, George SC. Airway epithelium stimulates smooth muscle proliferation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 41: 297–304, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mirzadegan T, Diehl F, Ebi B, Bhakta S, Polsky I, McCarley D, Mulkins M, Weatherhead GS, Lapierre JM, Dankwardt J, Morgans D, Jr, Wilhelm R, Jarnagin K. Identification of the binding site for a novel class of CCR2b chemokine receptor antagonists: binding to a common chemokine receptor motif within the helical bundle. J Biol Chem 275: 25562–25571, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Murasawa S, Mori Y, Nozawa Y, Masaki H, Maruyama K, Tsutsumi Y, Moriguchi Y, Shibasaki Y, Tanaka Y, Iwasaka T, Inada M, Matsubara H. Role of calcium-sensitive tyrosine kinase Pyk2/CAKbeta/RAFTK in angiotensin II induced Ras/ERK signaling. Hypertension 32: 668–675, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Nlend MC, Bookman RJ, Conner GE, Salathe M. Regulator of G-protein signaling protein 2 modulates purinergic calcium and ciliary beat frequency responses in airway epithelia. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 27: 436–445, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. O'Donnell RA, Richter A, Ward J, Angco G, Mehta A, Rousseau K, Swallow DM, Holgate ST, Djukanovic R, Davies DE, Wilson SJ. Expression of ErbB receptors and mucins in the airways of long term current smokers. Thorax 59: 1032–1040, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Oh P, Schnitzer JE. Segregation of heterotrimeric G proteins in cell surface microdomains. Gq binds caveolin to concentrate in caveolae, whereas Gi and Gs target lipid rafts by default. Mol Biol Cell 12: 685–698, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Patel HH, Murray F, Insel PA. Caveolae as organizers of pharmacologically relevant signal transduction molecules. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 48: 359–391, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Qin X, Wan Y, Wang X. CCL2 and CXCL1 trigger calcitonin gene-related peptide release by exciting primary nociceptive neurons. J Neurosci Res 82: 51–62, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rose MC, Voynow JA. Respiratory tract mucin genes and mucin glycoproteins in health and disease. Physiol Rev 86: 245–278, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rossi D, Zlotnik A. The biology of chemokines and their receptors. Annu Rev Immunol 18: 217–242, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sakai N, Wada T, Furuichi K, Shimizu K, Kokubo S, Hara A, Yamahana J, Okumura T, Matsushima K, Yokoyama H, Kaneko S. MCP-1/CCR2-dependent loop for fibrogenesis in human peripheral CD14-positive monocytes. J Leukoc Biol 79: 555–563, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Seasholtz TM, Majumdar M, Brown JH. Rho as a mediator of G protein-coupled receptor signaling. Mol Pharmacol 55: 949–956, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shaul PW, Anderson RG. Role of plasmalemmal caveolae in signal transduction. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 275: L843–L851, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shi G, Partida-Sanchez S, Misra RS, Tighe M, Borchers MT, Lee JJ, Simon MI, Lund FE. Identification of an alternative Gαq-dependent chemokine receptor signal transduction pathway in dendritic cells and granulocytes. J Exp Med 204: 2705–2718, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shimada H, Rajagopalan LE. Rho-kinase mediates lysophosphatidic acid-induced IL-8 and MCP-1 production via p38 and JNK pathways in human endothelial cells. FEBS Lett 584: 2827–2832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Soong G, Reddy B, Sokol S, Adamo R, Prince A. TLR2 is mobilized into an apical lipid raft receptor complex to signal infection in airway epithelial cells. J Clin Invest 113: 1482–1489, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sozzani S, Locati M, Zhou D, Rieppi M, Luini W, Lamorte G, Bianchi G, Polentarutti N, Allavena P, Mantovani A. Receptors, signal transduction, and spectrum of action of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 and related chemokines. J Leukoc Biol 57: 788–794, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Stamatovic SM, Keep RF, Kunkel SL, Andjelkovic AV. Potential role of MCP-1 in endothelial cell tight junction “opening”: signaling via Rho and Rho kinase. J Cell Sci 116: 4615–4628, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Takeyama K, Jung B, Shim JJ, Burgel PR, Dao-Pick T, Ueki IF, Protin U, Kroschel P, Nadel JA. Activation of epidermal growth factor receptors is responsible for mucin synthesis induced by cigarette smoke. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 280: L165–L172, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tarzami ST, Calderon TM, Deguzman A, Lopez L, Kitsis RN, Berman JW. MCP-1/CCL2 protects cardiac myocytes from hypoxia-induced apoptosis by a Gαi-independent pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 335: 1008–1016, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Taub DD, Proost P, Murphy WJ, Anver M, Longo DL, van Damme J, Oppenheim JJ. Monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), -2, and -3 are chemotactic for human T lymphocytes. J Clin Invest 95: 1370–1376, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Traves SL, Culpitt SV, Russell RE, Barnes PJ, Donnelly LE. Increased levels of the chemokines GROalpha and MCP-1 in sputum samples from patients with COPD. Thorax 57: 590–595, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ushio-Fukai M, Hilenski L, Santanam N, Becker PL, Ma Y, Griendling KK, Alexander RW. Cholesterol depletion inhibits epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation by angiotensin II in vascular smooth muscle cells: role of cholesterol-rich microdomains and focal adhesions in angiotensin II signaling. J Biol Chem 276: 48269–48275, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.