Abstract

Leukocyte [white blood cell (WBC)] adhesion and shedding of glycans from the endothelium [endothelial cells (ECs)] in response to the chemoattractant f-Met-Leu-Phe (fMLP) has been shown to be attenuated by topical inhibition of matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) with doxycycline (Doxy). Since Doxy also chelates divalent cations, these responses were studied to elucidate the relative roles of cation chelation and MMP inhibition. WBC-EC adhesion, WBC rolling flux, and WBC rolling velocity were studied in postcapillary venules in the rat mesentery during superfusion with the cation chelator EDTA or Doxy. Shedding and accumulation of glycans on ECs, with and without fMLP, were quantified by the surface concentration of lectin (BS-1)-coated fluorescently labeled microspheres (FLMs) during constant circulating concentration. Without fMLP, low concentrations of EDTA (1–3 mM) increased FLM-EC sequestration due to disruption of the permeability barrier with prolonged exposure. In contrast, with 0.5 μM Doxy alone, FLM adhesion remained constant (i.e., no change in glycan content) on ECs, and WBC adhesion increased with prolonged superfusion. Without fMLP, EDTA did not affect firm WBC-EC adhesion but reduced WBC rolling flux in a dose-dependent manner. With fMLP, EDTA did not inhibit WBC adhesion, whereas Doxy did during the first 20 min of superfusion. Thus, the inhibition by Doxy of glycan (FLM) shedding and WBC adhesion in response to fMLP results from MMP inhibition, in contrast to cation chelation. With either Doxy or the MMP inhibitor GM-6001, WBC rolling velocity decreased by 50%, as in the case with fMLP, suggesting that MMP inhibition reduces sheddase activity, which increases the adhesiveness of rolling WBCs. These events increase the effective leukocrit on the venular wall and increase firm WBC-EC adhesion. Thus, MMP inhibitors have both a proadhesion effect by reducing sheddase activity while exerting an antiadhesion effect by inhibiting glycocalyx shedding and subsequent exposure of adhesion molecules on the EC surface.

Keywords: endothelium, glycocalyx, leukocyte rolling velocity

the molecular composition and structure of the endothelial glycocalyx has become a subject of increasing focus in light of its role as a barrier to transvascular exchange of macromolecules and blood cell adhesion and a repository for receptors active in homeostasis (28, 29). It is well recognized that the glycocalyx consists primarily of a matrix of transmembrane and membrane glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins enmeshed in a matrix of the glycosaminoglycans heparan sulfate, chondroitin sulfate, and hyaluronan (28). The apparent thickness of the glycocalyx has been estimated by the exclusion of erythrocytes and macromolecules (34) to be on the order of 400–500 nm, which significantly exceeds the lengths of endothelial cell (EC) receptors involved in leukocyte [white blood cell (WBC)] rolling on the ECs (selectins) and firm adhesion to ECs (integrins). Studies of the lengths of these receptors have shown a range from 20 nm for the β2-integrin ligands to 30–40 nm for E- and P-selectins (31). Thus, given that the structure of the glycocalyx reflects a balance of the continued biosynthesis of glycans and their shear-dependent removal (1), it has been postulated that WBC-EC adhesion is strongly dependent on the thickness and composition of the glycocalyx (26). In this context, it has been shown that enzymatic removal of heparan sulfate with heparanase infusion in postcapillary venules results in an increased exposure of the β2-integrin ligand ICAM-1 and elevated WBC adhesion (6, 25, 26).

The labile nature of the glycocalyx has been demonstrated in models of the inflammatory process. It has been shown that topical stimulation of the endothelium for prolonged periods (20–120 min) with the cytokine TNF-α results in an increased porosity of the glycocalyx in the absence of WBC-EC adhesion (14). Significant shedding of components of the glycocalyx in coronary vessels has also been observed after perfusion of isolated hearts for 20 min with TNF-α, which was mitigated by the serine protease inhibitor antithrombin III (4). Acute activation of the endothelium in postcapillary venules with the chemoattractant f-Met-Leu-Phe (fMLP) has been found to induce a rapid (<5 min) shedding of glycans from the EC surface, as evidenced by a loss of lectin-laden microspheres bound to the EC surface (26). A recent study (27) has revealed that matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) on the surface of the venular endothelium are rapidly activated by superfusion of the mesenteric tissue with fMLP and may be inhibited by superfusion with subantimicrobial doses (0.5 μM) of the antibiotic doxycycline.

Doxycycline, a member of the tetracycline family of antibiotics, has been shown to be a broad-spectrum inhibitor of MMPs, a scavenger of divalent cations and ROS, an indirect inhibitor of serine proteinases, an inhibitor of the secretion of inflammatory cytokines, and blocker of nitric oxide synthase (10). MMPs represent a family of >24 zinc-dependent proteases that play a role in normal tissue remodeling during bone growth, wound healing, reproduction, cancer, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease (30). It has been found that MMP-1 and MMP-9 serve to cleave the endothelial insulin receptor and CD18 on leukocytes in the spontaneously hypertensive rat (7). Modification of the extracellular matrix by MMPs has been shown to be a critical step in angiogenesis (12) and atherosclerosis (21). MMP-2, MMP-7, and MMP-9 have been shown to be capable of directly cleaving chondroitin sulfate (11). In addition, MMP-1 has been shown to cleave the heparan sulfate proteoglycan syndecan-1 (8). MMPs can be stored within and released by the endothelium. It has been shown (33) that both the active and proactive forms of MMP-2 and MMP-9 are stored in vesicles within the EC. Similarly, MMP-7, in both its constitutive and latent forms, has a high affinity for, and binds to, heparan sulfate (35). These findings suggest that mechanisms exist by which MMPs can be rapidly released by ECs without the need for upregulation of mRNA. Inhibition of MMPs occurs naturally by a class of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs). TIMPs comprise a family of four different molecules made unique by their expression, localization, and inhibitory activity. Much like the MMPs, TIMPs are capable of binding heparan sulfate and chondroitin sulfate in the glycocalyx (35).

The inhibitory effects of doxycycline on the concurrent events of WBC-EC adhesion and glycan shedding in response to fMLP support the hypothesis that shedding of the glycocalyx exposes adhesion molecules that are constitutively expressed on the EC surface, thus promoting enhanced adhesion. However, the well-known inhibition of WBC adhesion by chelation of divalent cations (2) and the ability of doxycycline to chelate divalent cations (20) raise the question of whether the inhibitory effects of doxycycline arise from the chelation of cations required for selectin and integrin adhesion (15, 16) or chelation of the central zinc that plays a role in the activation of MMP proenzymes. To address this question, the present study was undertaken to examine the rolling and adhesion of WBCs on the EC in response to graded concentrations of EDTA with and without the presence of fMLP and/or doxycycline. The aim of the present study was to determine if levels of EDTA that inhibit WBC rolling or adhesion on the walls of postcapillary venules in the mesentery (rat) were sufficient to inhibit the shedding of glycans from the EC surface, thus providing evidence for the independent actions of chelation and MMP inhibition. To this end, the following three separate sets of experiments were performed while WBC adhesion and rolling were observed in postcapillary venules of the rat mesentery: 1) superfusion of the mesenteric tissue with either graded concentrations of EDTA or doxycycline, 2) superfusion of the mesentery with the chemoattractant fMLP with varied concentrations of EDTA or doxycycline added to the suffusate, and 3) measurement of the rolling velocity of WBCs on the EC surface to quantify WBC-EC adhesive interactions during superfusion with either EDTA, MMP inhibitors [doxycycline and ilomastat (GM-6001)], or fMLP.

METHODS AND MATERIALS

Animal preparation.

All animal experiments reported herein conformed with the “Guiding Principles in the Care and Use of Animals” established by the American Physiological Society, and all protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The Pennsylvania State University.

Male Wistar rats, weighing 250–400 g, were anesthetized with Inactin (125 mg/kg ip), tracheostomized, and allowed to breathe under spontaneous respiration. The right jugular vein was cannulated with polyethylene tubing (PE-50) for the administration of supplemental anesthetic, as needed, to maintain a surgical plane of anesthesia. The right carotid artery was also cannulated with PE-50 tubing and connected to a strain-gage pressure transducer to monitor central arterial pressure, which averaged 125 mmHg. A rectal probe was used to monitor core temperature, which was maintained between 36 and 37°C with the aid of a heating pad.

Intravital microscopy and experiment protocols.

The intestinal mesentery was exteriorized through a midline abdominal incision and placed on a glass pedestal to facilitate viewing under either bright-field microscopy by either trans- or incident illumination. Fluorescence microscopy was performed under incident Hg lamp illumination with a dichroic mirror and filters appropriate for fluorescein excitation and emission spectra. The tissue was superfused with HEPES-buffered Ringer solution (pH 7.4) at a temperature of 37.0°C. Solutions of fMLP (10−7 M, Sigma, St Louis, MO), doxycycline (0.5 μM, Sigma, St Louis, MO), and EDTA (1.0 or 3.0 mM) were prepared in HEPES-buffered Ringer solution to superfuse the tissue.

To elucidate the shedding of glycans from the EC surface, fluorescently labeled microspheres (FLMs) coated with the lectin Bandeiraea simplificifolia (BS-1, Sigma) were infused into the circulation. A bolus of coated FLMs was infused at 2 × 1012 spheres·ml−1·kg−1 via the jugular vein to obtain a circulating concentration of 106 FLMs/mm3. The circulating concentration of FLMs was maintained at that level by an intravenous infusion of 2 × 1010 spheres·kg−1·min−1 via the jugular vein using a syringe pump (model PHD-2000, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA). Invariance of the circulating concentration of FLMs was verified by measurement of the FLM concentration in blood samples withdrawn from the carotid artery and examined with a hemocytometer under fluorescence microscopy. After a 20-min control period to permit stabilization of the microvasculature, tissues were superfused for the duration of the experiment with Ringer solution containing either 1 mM EDTA, 3 mM EDTA, or 0.5 μM doxycycline with or without the addition of 10−7 M fMLP.

To examine the effects of MMP inhibition on the adhesive interactions between WBCs and ECs during leukocyte rolling, a separate set of experiments was conducted without the use of microspheres. For these experiments, the mesentery was superfused with either 3 mM EDTA, 0.5 μM doxycycline, 2.6 μM of the hydroxamic acid zinc chelator GM-6001 (US Biological), or 10−7 M fMLP, with each in Ringer solution.

Microsphere preparation.

Methods for the preparation of the lectin-coated microspheres have been previously described in detail (25) and are summarized as follows. Fluorescent (yellow-green) carboxylate-modified polystyrene microspheres, 0.1 μm in diameter (FLMs, Fluospheres, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), were labeled by covalent linkage (carbodiimide reaction) of the lectin BS-1 (Sigma), which preferentially binds to galactose moities on the EC surface. The protein content on the FLMs was determined by assay of the uptake of lectin from the labeling solutions using a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Columbia, MD) and found to average 2 × 104 lectin molecules/microsphere.

Measurements.

Postcapillary venules ranging in width from 25 to 50 μm were viewed using a Zeiss water-immersion ×40/0.75 numerical aperture objective. The image of a microscopic field was projected onto a low-light-level silicon-intensified target camera (model 66, Dage-MTI, Michigan City, IN) for an effective width of the video field of 100 μm. Images of FLMs adhered to the endothelium in a 100-μm length of venule were recorded while focusing above and below the microvessel diametral plane. The number of FLMs adhered per 100 μm were counted during offline video analysis. An in vitro calibration study (22) of the adhesion of FLMs to glass surfaces to which various concentrations of chondroitin sulfate were covalently linked revealed that the number of bound FLMs was proportional to the glycosaminoglycan concentration and was invariant with wall shear stresses over a physiological range of 1–50 dyn/cm2 with or without the presence of 10−7 M fMLP.

Red blood cell velocity (VRBC) in arterioles and venules was measured with the two-slit photometric technique using a self-tracking correlator (IPM, San Diego, CA). The mean velocity of blood (Vmean) was calculated from the following relationship: Vmean = VRBC/1.6 (24). The vessel diameter was measured by the video image shearing technique using an image shearing monitor (IPM). Wall shear rates were estimated from the following Newtonian-flow relationship for flow in a cylindrical tube: wall shear rate = 8Vmean/vessel diameter.

The flux (cells/min) and velocity (VWBC, in μm/s) of WBCs rolling along the endothelium (ECs) was determined from frame-by-frame video analysis. Flux was obtained by counting the number of cells per minute passing a reference mark along the vessel length, and VWBC was measured from the axial displacement of WBCs of cells that exhibited rolling motion on the EC surface. The number of WBCs and FLMs adhered to the ECs were measured by frame-by-frame analysis of video recordings and expressed as the number adhering per 100 μm of venule length. Adhered WBCs and FLMs were judged to be firmly adhered if they remained stationary for at least 5 s. Illustrative video scenes of WBC-EC and FLM-EC adhesion have been shown previously (27).

Statistical analysis of trends in the data were performed using SigmaStat (SPSS) using either Student's t-test for paired tests or the Holm-Sidak method for ANOVA of multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

WBC adhesion and glycan shedding in response to EDTA and doxycycline.

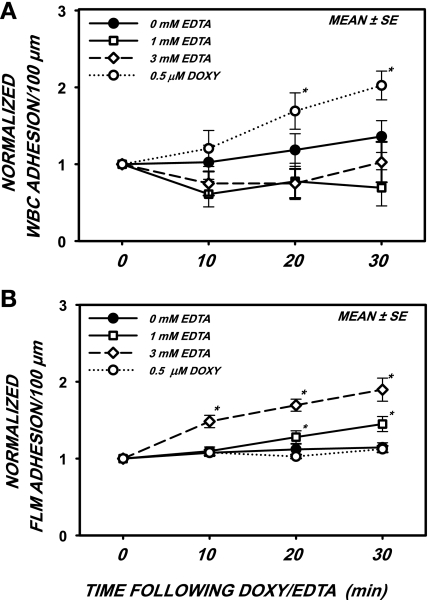

The responses to superfusion of the mesentery with either 0 (control), 1, or 3 mM EDTA or 0.5 μM doxycycline are shown in Fig. 1 for leukocyte (WBC) adhesion (A) and lectin BS-1-coated FLM adhesion (B) to the endothelium. All data were normalized with respect to their initial values immediately before the onset of the superfusion, which are shown in Table 1. No significant differences between initial hemodynamic and adhesion variables were found for control, 3 mM EDTA, and doxycycline treatments. However, there appeared to be a significant increase in baseline VRBC and WBC flux before the application of 1 mM EDTA. These anomalous increases were attributed to arteriolar dilation in a subset of microvessels or tissues studied. As shown in Fig. 1A, the effects of 1 and 3 mM EDTA on WBC adhesion were not significant for the entire 30-min observation period. However, with doxycycline, a significant rise in WBC adhesion occurred after 20 and 30 min. As subsequently shown, this rise was attributable to an increased effective density of WBCs (number of cells/vessel length) making contact with the ECs. The effect of EDTA on FLM adhesion (Fig. 1B) was time and concentration dependent, with significant increases at 20 and 30 min for 1 mM EDTA and at all times for 3 mM EDTA.

Fig. 1.

Adhesion of leukocytes [white blood cells (WBC); A] and fluorescently labeled microspheres (FLMs; B) per 100-μm length of postcapillary venule in the rat mesentery after superfusion of the tissue with either 0.5 μM doxycycline (Doxy) or EDTA at the indicated concentrations. A: with Doxy alone, WBC adhesion increased significantly over a 30-min period, presumably due to enhanced frequency of contact due to inhibition of sheddase activity, which cleaves adhesion molecules. EDTA had no effect on WBC adhesion. B: FLM adhesion rose significantly during superfusion with EDTA after 20 min with 1 mM EDTA and after 10 min with 3 mM EDTA due to disruption of the vascular wall and leakage of FLMs into the perivascular space, which could not be distinguished from the EC surface. *P < 0.05 by ANOVA.

Table 1.

Initial values of hemodynamic parameters before treatment

| Control (0 mM EDTA) | 1 mM EDTA | 3 mM EDTA | 0.5 μM Doxycycline | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of venules | 19 | 12 | 12 | 13 |

| Diameter, μm | 37.6 ± 2.6 | 36 ± 2.9 | 35.8 ± 3.3 | 38.3 ± 3.0 |

| FLM adhesion, no. of FLMs/100-μm vessel length | 13.4 ± 1.0 | 11.1 ± 0.9 | 13.6 ± 1.5 | 10.4 ± 0.6 |

| WBC adhesion, no. of WBCs/100-μm vessel length | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.12 | 1.7 ± 0.16 | 1.4 ± 0.2 |

| VRBC, mm/s | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 5.7 ± 0.8 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 4.2 ± 0.4 |

| WBC rolling flux, no. of WBCs/min | 10.8 ± 1.0 | 21.0 ± 2.5 | 12.6 ± 2.3 | 10.8 ± 1.8 |

Values are mean ± SE obtained before superfusion of the mesenteric tissue with the indicated treatments. Fluorescently labeled microsphere (FLM) adhesion and white blood cell (WBC) adhesion are the numbers of lectin-coated microspheres and leukocytes, respectively, adhered per 100 mm of venule length. All initial parameters were not significantly different from control except for centerline red blood cell velocity (VRBC) and WBC rolling flux before 1 mM EDTA (P < 0.02), which most likely resulted from arteriolar vasodilation in a subset of micovessels or tissues.

Rolling WBC flux in response to EDTA and doxycycline.

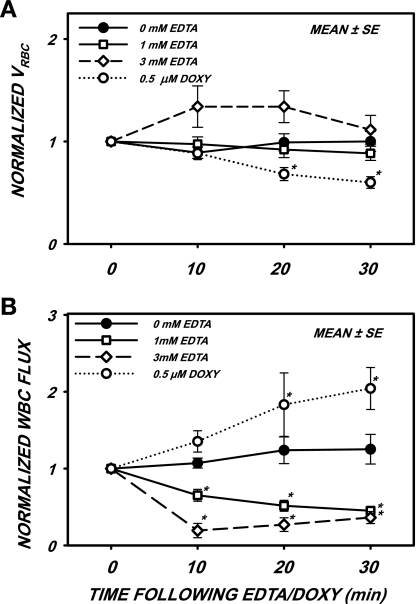

As shown in Fig. 2A, normalized VRBC remained statistically invariant with time during superfusion with 0 (control), 1, and 3 mM EDTA, thus suggesting an invariance of wall shear rates and stresses. Initial values of all parameters at time 0 are shown in Table 1. The 30% increase in VRBC with 3 mM EDTA was not significant due to the large SD. Superfusion with doxycycline resulted in no significant changes at 10 min but a significant decrease at 20 and 30 min (P < 0.001). This decrease in VRBC was most likely due to the significant increase in WBC adhesion (Fig. 1A) and attendant obstruction of the venule lumen.

Fig. 2.

Normalized red blood cell velocity (VRBC; A) and WBC rolling flux (B) after superfusion with either 0.5 μM Doxy or EDTA at the indicated concentrations. A: VRBC increased by 30% with 3 mM EDTA, but not significantly. A small but significant decrease in VRBC incurred after superfusion with Doxy for 20 min, possibly due to the obstruction of venules by firmly adhered WBCs (Fig. 1A). B: WBC flux fell significantly from control with EDTA during the entire 30-min superfusion period and rose significantly after 20 min with Doxy, possibly due to the inhibition of sheddase activity, which may normally limit the number of adhesion molecules on the endothelial cell (EC) surface. *P < 0.05 by ANOVA.

The normalized rolling WBC flux is shown in Fig. 2B for superfusion with EDTA and doxycycline. Under control (0 mM EDTA) conditions, the rolling flux remained constant throughout the 30-min observation period (P = 0.442). With 1 and 3 mM EDTA, flux was significantly reduced below initial values at all times (P < 0.001). With doxycycline, however, WBC flux was not significantly elevated at 10 min but rose significantly at 20 and 30 min (P < 0.03). As discussed below, this rise in flux was attributed to inhibition of sheddase activity by doxycycline with an attendant increase in adhesion molecules on the EC surface that facilitated rolling contact.

WBC adhesion, flux, and glycan shedding in response to fMLP.

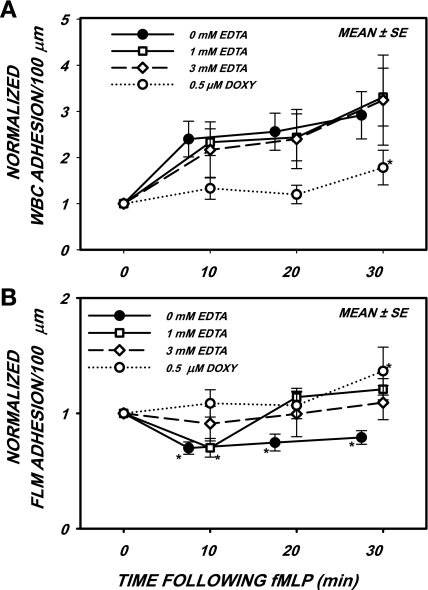

The effect of cation chelation with EDTA on the response to topical application of the chemoattractant fMLP over a 30-min period is shown in Fig. 3. All data were normalized relative to their initial values before superfusion with fMLP, as shown in Table 2. With the addition of 1 mM EDTA (Fig. 3A), an increase in WBC adhesion was significant at all times after the onset of fMLP. With the addition of 3 mM EDTA, although the rise at 10 min after fMLP was significant (P < 0.06 by t-test), the elevated adhesion observed over the entire 30-min time period was not significant (P = 0.126 by ANOVA) because of the large SE of the response at 30 min. Superfusion with 0.5 μM doxycycline abolished the fMLP response, as previously shown (27), and the rise over the 30-min period was not significant (P = 0.156) except for the value at 30 min.

Fig. 3.

WBC adhesion (A) and FLM adhesion (B) per 100-μm venular length after superfusion of the mesentery with 10−7 M f-Met-Leu-Phe (fMLP) with the addition of either 0.5 μM Doxy or EDTA at the indicated concentrations. A: WBC adhesion rose significantly for all concentrations of EDTA over the entire 30-min period and did not rise significantly during superfusion with Doxy until after 30 min. B: FLM adhesion fell significantly within 10 min of onset of fMLP under 0 (control) and 1 mM EDTA, subsequently rose with 1 mM EDTA, and failed to fall with 3 mM EDTA. The late rise in FLM adhesion with 1 mM EDTA and the lack of decline with 3 mM EDTA appears to arise from a disruption of the venule permeability barrier, which caused extravasation of FLMs, which confounded accurate FLM counts on the EC surface. *P < 0.05 by ANOVA.

Table 2.

Initial values of hemodynamic variables before superfusion with fMLP

| Control (0 mM EDTA) | 1 mM EDTA | 3 mM EDTA | 0.5 μM Doxycycline | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of venules | 21 | 16 | 17 | 10 |

| Diameter, μm | 33.6 ± 1.7 | 40 ± 2.9 | 41.2 ± 2.3 | 31 ± 6.3 |

| FLM adhesion, no. of FLMs/100-μm vessel length | 11.6 ± 1.2 | 10.6 ± 1.0 | 10.9 ± 1.1 | 8.2 ± 0.8 |

| WBC adhesion, no. of WBCs/100-μm vessel length | 3.0 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.3 |

| VRBC, mm/s | 4.6 ± 0.6 | 4.1 ± 0.6 | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 3.6 ± 0.4 |

| WBC rolling flux, no. of WBCs/min | 13.9 ± 1.9 | 12.7 ± 1.2 | 12.7 ± 2.3 | 10.6 ± 1.7 |

Values are mean ± SE obtained before superfusion of the mesenteric tissue with the indicated treatments. Each of the above agents were added to 10−7 M f-Met-Leu-Phe (fMLP) in Ringer solution. All initial parameters were not significantly different from control.

To illustrate the shedding of glycans in response to fMLP, the loss of lectin-coated FLMs after fMLP is shown in Fig. 3B. During the first 10-min exposure to fMLP, 1 mM EDTA shedding of FLMs was significant (P < 0 .001). In contrast, EDTA at 3 mM appeared to inhibit the fMLP-induced loss of FLMs, since the FLM count did not fall below initial values (P = 0.869). As previously shown (27), the response to fMLP in the presence of 0.5 μM doxycycline was attenuated (P = 0.237) and rose after 30 min. The late rise of FLM count with doxycycline and 1 mM EDTA as well as the entire time course with 3 mM EDTA appear to arise from a disruption of the permeability of the venular wall, which was clearly evident with the addition of 5 mM EDTA to the superfusate. With 5 mM EDTA, extravasation of FLMs into the perivascular space was pronounced and accompanied by thrombus formation in response to the fluorescence excitation. The severity of this response to 5 mM EDTA precluded the acquisition of meaningful FLM adhesion and flow data.

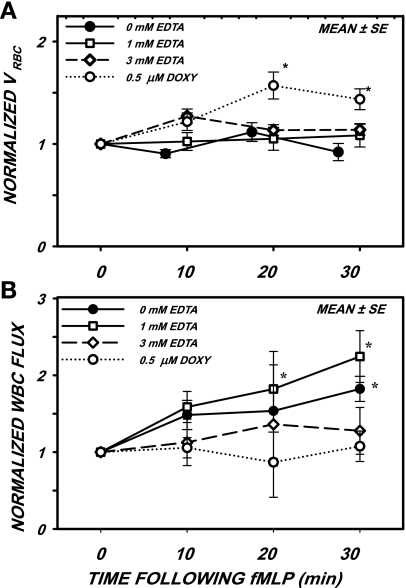

The effects of EDTA and doxycycline on the flux of WBCs that rolled along the venular wall in response to fMLP is shown in Fig. 4. During these experiments, VRBC (Fig. 4A) varied insignificantly by ∼25% in response to fMLP except for the case of doxycycline at 20 and 30 min, where a significant 50% rise in VRBC occurred (P < 0.001). These latter increases in VRBC were not reflected by significant changes in WBC flux. The normalized WBC flux (Fig. 4B) remained statistically invariant throughout the 30-min period for 3 mM EDTA (P = 0.962) and doxycycline (P = 0.549). In contrast, a significant rise in flux was found for control (0 mM EDTA, P < 0.004) and 1 mM EDTA (P < 0.03).

Fig. 4.

Normalized VRBC (A) and WBC rolling flux (B) after superfusion with 10−7 M fMLP with the addition of either 0.5 μM Doxy or EDTA. A: EDTA had little effect on VRBC during the 30-min period, whereas Doxy resulted in a small yet significant rise after 20 min, possibly due to arteriolar dilation. B: WBC flux rose significantly in response to fMLP (0 mM EDTA) and rose to a much greater amount with the addition of 1 mM EDTA. With the addition of 3 mM EDTA, WBC flux failed to rise, which was suggestive of interference with adhesive bonds during rolling. With the addition of Doxy, WBC flux remained invariant over the 30-min period. *P < 0.05 by ANOVA.

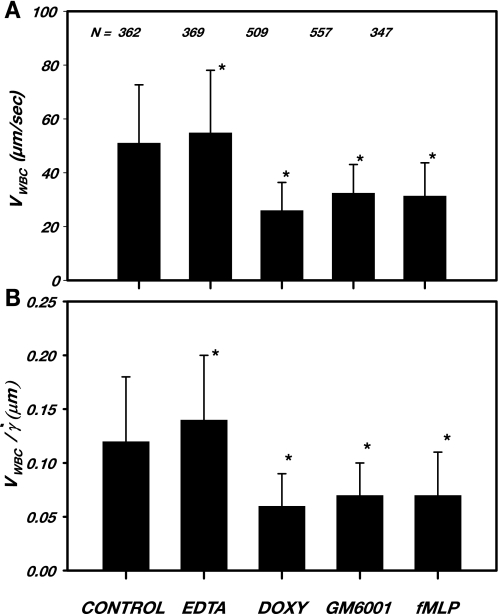

Leukocyte rolling velocity.

To gain insight into the adhesive forces between leukocytes and the endothelium, measurements of VWBC and estimates of wall shear rate were made during superfusion of the tissue with the agents used. As shown in Fig. 5, VWBC under control conditions (Ringer solution alone) was consistent with prior measurements (23) and was slightly elevated (7%) by superfusion with 3 mM EDTA (P < 0.05). Superfusion with doxycycline or the hydroxamic acid MMP inhibitor GM-6001 significantly reduced VWBC by 50% (P < 0.01) and 37% (P < 0.02), respectively. Superfusion with fMLP significantly reduced VWBC by 39% (P < 0.03). To exclude the possibility that shear rate variations (and hence wall shear stresses) could influence this comparison, a large number of measurements were made in multiple venules with different diameters and VRBC values, as shown in Table 3. No significant differences among diameter, VRBC, or wall shear rate were apparent for each treatment. It should be noted, however, that the venules studied for the measurement of VWBC were 20% smaller in diameter compared with those observed in the no-fMLP group (Table 1) or the fMLP group (Table 2). This difference arose from the greater numbers of rolling WBCs compared with those exhibiting transient adhesion or saltation in these smaller venules. A longer duration of rolling (at least one or two cell revolutions) was needed to obtain an average rolling velocity, and, hence, fewer larger venules were studied where WBCs were more rapidly entrained by the red blood cell stream. The normalization of VWBC by prevailing wall shear rates (wall shear rate = 8Vmean/vessel diameter) accounted for these minor differences in diameter, as evidenced by the similarity of trends in the ratio of VWBC to wall shear rate (Fig. 5B) for each treatment compared with the results shown in Fig. 5A, which also suggested a negligible effect of wall shear rates and stresses. Hence, the variations observed in VWBC may be attributed mainly due to alterations in the adhesive interactions between WBCs and ECs.

Fig. 5.

A: rolling WBC velocity (VWBC) under control conditions (Ringer solution alone) and with the addition of either 3 mM EDTA, 0.5 μM Doxy, 2.6 μM GM-6001, or 10−7 M fMLP. A large number (N) of WBCs were observed over a 30-min period of superfusion with the indicated agents for 10–16 venules, each over a broad range of estimated wall shear rates (γ̇), as shown in Table 3. B: rolling VWBC normalized by estimated wall shear rate indicated that the observed reductions in VWBC were not shear rate dependent. VWBC fell significantly with matrix metalloproteinase inhibition by either Doxy or the zinc chelator GM-6001, suggesting enhanced adhesion between WBCs and ECs due to increased adhesion receptors attendant to reduced sheddase activity. VWBC was also reduced with fMLP due to increased exposure of adhesion receptors after shedding of the glycocalyx or conformational changes of the receptors. *Statistically different from control; see results for details.

Table 3.

Hemodynamic variables during leukocyte rolling on the venular endothelium

| Control (Ringer Solution) | 3 mM EDTA | 0.5 μM Doxycycline | 2.8 μM GM-6001 | 10−7 M fMLP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Rolling WBCs | 362 | 369 | 509 | 557 | 347 |

| Number of venules | 10 | 10 | 15 | 14 | 16 |

| Vessel diameter, μm | 26.7 ± 5.2 | 29.8 ± 6.7 | 29.6 ± 6.0 | 30.6 ± 5.6 | 25.5 ± 6.3 |

| VRBC, mm/s | 2.6 ± 1.1 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 2.9 ± 1.3 | 2.8 ± 1.0 | 2.5 ± 0.8 |

| VWBC, μm/s | 51.1 ± 21.6 | 54.9 ± 23.2 | 26.0 ± 10.4 | 32.5 ± 10.6 | 31.4 ± 12.3 |

| γ̇, s−1 | 499 ± 196 | 418 ± 94 | 495 ± 180 | 451 ± 102 | 510 ± 156 |

| VWBC/γ̇, μm | 0.12 ± 0.06 | 0.14 ± 0.06 | 0.06 ± 0.03 | 0.07 ± 0.03 | 0.07 ± 0.04 |

| R2 value | 4.70 × 10−4 | 4.98 × 10−5 | 3.00 × 10−4 | 9.99 × 10−5 | 3.30 × 10−3 |

| P value | 0.337 | 0.446 | 0.348 | 0.409 | 0.143 |

Values shown are means ± SD. VWBC, rolling WBC velocity; γ̇, calculated Newtonian wall shear rate; R2, regression coefficient of VWBC vs. γ̇; P, probability of the null hypothesis for the regression slope (t-test). For all treatments, VWBC was invariant with γ̇ for 200 ≤ γ̇ ≤700 s−1, and the regression slope was not significantly different from zero.

DISCUSSION

The inhibition of MMP activation with agents that chelate divalent cations necessary for leukocyte rolling and firm adhesion raises the challenging question of whether the avidity of the adhesive bond is being affected or whether MMP activity mitigates steric interference of the adhesion process by the endothelial glycocalyx. Receptor-mediated adhesion of leukocytes to the endothelium has traditionally been viewed in light of the affinity of adhesion molecules and their upregulation in response to cellular signaling processes (31). The time course of WBC-EC adhesion in response to fMLP has been well characterized in terms of a rapid influx of rolling and adhering WBCs within the first 5 min of exposure, which is dependent on the activation of G protein-coupled receptors on the EC (26). This initial adhesion is followed by a shear-dependent plateau of steady-state adhesion whose duration depends on the magnitude of shearing stresses that act to remove adherent WBCs (17). The long-term adhesion of WBCs with fMLP is similar to that in response to topical application of TNF-α, where protein synthesis drives the response (9, 14). In parallel with WBC adhesion, the shedding of glycans from the EC surface follows a similar trend: a rapid release of components (26) accompanied by a shear-dependent synthesis of new glycans (1) that result in a new steady-state level, which is also similar to glycan shedding in response to TNF-α (14). After the loss of glycans with fMLP, the glycocalyx is gradually reconstituted by biosynthesis of new glycans, as evidenced by the binding of circulating lectin-coated microspheres (26). Within this framework, the present study aimed to elucidate leukocyte rolling on and firm adhesion to ECs in light of 1) cation chelation with EDTA and 2) inhibition of MMP activation with doxycycline or GM-6001 in both a normal flow state and with stimulation of the endothelium with the chemoattractant fMLP. In each case, the effects of cation chelation or MMP inhibition on glycan shedding or accumulation have been quantified using the number of lectin-coated microspheres (FLMs) adherent to the EC surface as an indicator of the concentration of glycans on the EC surface.

Cation chelation versus MMP inhibition.

The present results for WBC-EC rolling and adhesion are consistent with previous studies of the individual effects of EDTA and fMLP. The general conclusion drawn from the present data is that superfusion of the tissue with a low concentration of EDTA (1 mM), which significantly diminishes WBC flux (Fig. 2B), does not affect microsphere accumulation on the EC surface (Fig. 1B). This result suggests that glycan levels on the EC are not affected by cation chelation. A previous study (20) of the binding capacity of doxycycline for divalent cations revealed that doxycycline may bind to either Ca2+ or Mg2+ cations in molar ratios from 2:1 to 1:2, depending on pH and temperature, whereas EDTA typically binds to Ca2+ in a 1:1 molar ratio. Hence, inasmuch as 0.5 μM doxycycline has a much lower potential for binding divalent cations than 1 mM EDTA, it appears that the effects of doxycycline on WBC rolling and adhesion arise from its ability to inhibit protease activity. The increased firm adhesion of WBCs due to doxycycline (Fig. 1A) and the attendant increase in rolling WBC flux (Fig. 2B) are consistent with the hypothesis that doxycycline inhibits the normal sheddase activity that is responsible for cleaving selectins and other adhesion molecules on the EC surface. Sheddases (defined as membrane-bound proteases that cleave the ectodomain of membrane-bound proteins) have been shown to play a major role in affecting the composition of the glycocalyx (32). Cleavage of the hyaluronan receptor, CD44, by members of the a disintegrin and metalloproteinase (ADAM) family of cell surface proteases may affect hyaluronan binding to the EC and has been shown to affect cell-cell adhesion and cell-matrix interactions (30, 32). It should be noted that the adhesion response to doxycycline is significantly delayed and of lesser magnitude compared with that with fMLP alone (Fig. 3A).

Leukocyte rolling and adhesion to the endothelium.

Inhibition of sheddase activity appears to result in a significantly lower rolling VWBC (Fig. 5). The reduced rolling velocity may arise from greater adhesive interactions concomitant to an increase in leukocyte-binding sites resulting from inhibition of natural shedding on the EC surface. Similar results have been demonstrated by the inhibition of L-selectin shedding from the WBC by the metalloprotease inhibitor KD-IX-73-4, as observed in postcapillary venules of hamster cremaster muscle (13). It has also been shown that reduced rolling VWBC occurs after exposure of cremaster venules to TNF-α (18). Although these results were attributed to conformational changes of adhesion receptors in response to TNF-α, this trend may reflect the shedding of glycans from the EC surface, as noted previously (14), and the enhanced exposure of adhesion ligands (e.g., ICAM-1), as suggested by the reductions in rolling velocity found here in response to fMLP (Fig. 5).Given that the flux of WBCs along the vascular endothelium is proportional to the product of the effective number of WBCs present per length of venule and the rolling VWBC, i.e., flux = (number of WBCs/vessel length) × VWBC, the significant increase in WBC flux with superfusion of doxycycline (Fig. 2) must occur in response to an increased leukocrit at the wall (number of WBCs/vessel length) that counters the reduction in rolling velocity. This increase in effective leukocrit may also be responsible for the slow (compared with that caused by fMLP) rise in firm WBC adhesion in response to doxycycline (Fig. 1), which may result from the increased frequency of WBC-EC contact events.

Effects of EDTA concentration on WBC-EC adhesion and FLM sequestration.

The low levels of EDTA used in the present experiments were an order of magnitude less than that traditionally used to inhibit in vivo WBC-EC rolling and adhesion (2). In these seminal studies, topical application of 100 mM EDTA was demonstrated to reduce WBC rolling flux to zero within 5 min of the onset of superfusion. In an attempt to elucidate the effects of graded concentrations of EDTA on WBC rolling and adhesion, the present study demonstrated significant time-dependent effects of chelation. As shown in Fig. 2B, the greater the concentration of EDTA, the more rapid the onset of attenuation of WBC rolling flux, presumably due to inhibition of WBC-selectin binding necessary to support rolling. As shown in Fig. 1B, 3 mM EDTA caused a rise in FLM adhesion within 10 min, which progressed in magnitude over the subsequent 20-min period. With 1 mM EDTA, the onset of FLM adhesion occurred after 20 min of superfusion. These effects are believed to be a direct result of disruption of the permeability barrier and structural integrity of the venular wall with prolonged exposure to EDTA. Attempts to superfuse the tissue with 5 mM EDTA for 30 min were confounded by severe extravasation of red blood cells and FLMs and increased susceptibility to thrombus formation. It has long been recognized that removal of calcium from the in vivo perfusion media results in a disruption of the permeability barrier and ultimately leads to capillary and venular stasis (36). An ultrastructural study (5) after perfusion of microvessels in the rat intestinal mucosa revealed slight damage to the vessel structure after 10 min of perfusion with 25 mM EDTA and pronounced damage after perfusion with 100 mM EDTA.

It was found here that when 5 mM EDTA was applied with the addition of fMLP (as shown in Fig. 3), loss of the anticoagulant properties of the EC surface, presumably by shedding of the glycocalyx and bound antithrombin III (29), resulted in thrombus formation and venular stasis. Hence, it appears that increasing concentrations and prolonged exposure to EDTA lead to exposure of the subendothelial space and the onset of thrombus formation. The lesser concentrations of EDTA used here (1 and 3 mM) also produced subtle adverse effects, as indicated by the accumulation of 0.1-μm-diameter FLMs (Fig. 1). With 1 mM EDTA, a significant rise in accumulation was noted at 20 min, and with 3 mM EDTA, a much greater rise began at 10 min. This anomalous accumulation of FLMs was attributed to either increased porosity of the glycocalyx or opening of the intercellular clefts, which allowed passage of the FLMs into the perivascular space. It should be noted that limited optical resolution precluded making a distinction between FLMs bound to the EC surface and those in the perivascular space. However, previous studies using adhesion of lectin-laden FLMs to indicate increased glycan content during ischemia demonstrated that increased numbers of FLMs that were bound to the EC surface were rapidly washed out after the resumption of venular blood flow.

Doxycycline as an anti-inflammatory agent.

The present data also reveal the anomalous behavior of doxycycline as an anti-inflammatory agent. While doxycycline mitigates the acute increase in WBC-EC adhesion in response to fMLP (Fig. 3A), presumably by inhibition of glycocalyx shedding, the inhibition of constitutive sheddase activity in the absence of fMLP results in a slow but steady increase in WBC adhesion with time (Fig. 1A). For both fMLP and MMP inhibitors (doxycycline and GM-6001) individually, rolling VWBC was significantly reduced (Fig. 5). In the case of fMLP alone, previous studies have revealed that shedding of the glycocalyx exposes more ICAM-1 to promote adhesive interactions (25) and that rolling velocity is reduced (23). Given that reduced rolling VWBC raises the frequency of WBC-EC contact events, it is logical to observe both pro- and antiadhesive effects of MMP inhibition. Thus, while it is generally acknowledged that MMPs serve to modulate inflammation by direct proteolytic processing of inflammatory mediators, such as chemokines and chemoattractants (19), it is apparent that more incisive studies of the relative roles of specific MMP inhibitors are needed to design therapeutic treatments.

In summary, the results from the present study suggest that the anti-inflammatory effects of doxycycline arise from its inhibition of MMP activation, in contrast to its chelation of divalent cations. Although many studies have attributed the increased adhesiveness of WBCs induced by fMLP to conformational changes in integrin receptors (e.g., CD18) on the WBC (3), the coincident removal of steric hindrance to the adhesion process by shedding of the glycocalyx appears to be an important mechanism that is affected by extracellular or membrane-bound proteases. The dual role of MMP inhibition to enhance the frequency of WBC-EC contact through diminished sheddase activity while limiting the availability of adhesion ligands on the EC surface remains to be fully delineated in light of the large number of proteases and their inhibitors resident at the adhesion interface.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Research Grant R01-HL-39286.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1. Arisaka T, Mitsumata M, Kawasumi M, Tohjima T, Hirose S, Yoshida Y. Effects of shear stress on glycosaminoglycan synthesis in vascular endothelial cells. Ann NY Acad Sci 748: 543–554, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Atherton A, Born GV. Quantitative investigations of the adhesiveness of circulating polymorphonuclear leucocytes to blood vessel walls. J Physiol 222: 447–474, 1972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beals CR, Edwards AC, Gottschalk RJ, Kuijpers TW, Staunton DE. CD18 activation epitopes induced by leukocyte activation. J Immunol 167: 6113–6122, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chappell D, Hofmann-Kiefer K, Jacob M, Rehm M, Briegel J, Welsch U, Conzen P, Becker BF. TNF-α induced shedding of the endothelial glycocalyx is prevented by hydrocortisone and antithrombin. Basic Res Cardiol 104: 78–89, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Clementi F, Palade GE. Intestinal capillaries. II. Structural effects of EDTA and histamine. J Cell Biol 42: 706–714, 1969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Constantinescu AA, Vink H, Spaan JA. Endothelial cell glycocalyx modulates immobilization of leukocytes at the endothelial surface. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 23: 1541–1547, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. DeLano FA, Schmid-Schonbein GW. Proteinase activity and receptor cleavage: mechanism for insulin resistance in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Hypertension 52: 415–423, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Endo K, Takino T, Miyamori H, Kinsen H, Yoshizaki T, Furukawa M, Sato H. Cleavage of syndecan-1 by membrane type matrix metalloproteinase-1 stimulates cell migration. J Biol Chem 278: 40764–70, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fingar VH, Taber SW, Buschemeyer WC, ten Tije A, Cerrito PB, Tseng M, Guo H, Johnston MN, Wieman TJ. Constitutive and stimulated expression of ICAM-1 protein on pulmonary endothelial cells in vivo. Microvasc Res 54: 135–144, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Golub LM, Lee HM, Ryan ME, Giannobile WV, Payne J, Sorsa T. Tetracyclines inhibit connective tissue breakdown by multiple non-antimicrobial mechanisms. Adv Dent Res 12: 12–26, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gronski TJ, Jr, Martin RL, Kobayashi DK, Walsh BC, Holman MC, Huber M, Van Wart HE, Shapiro SD. Hydrolysis of a broad spectrum of extracellular matrix proteins by human macrophage elastase. J Biol Chem 272: 12189–94, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Haas TL, Milkiewicz M, Davis SJ, Zhou AL, Egginton S, Brown MD, Madri JA, Hudlicka O. Matrix metalloproteinase activity is required for activity-induced angiogenesis in rat skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 279: H1540–H1547, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hafezi-Moghadam A, Thomas KL, Prorock AJ, Huo Y, Ley K. L-selectin shedding regulates leukocyte recruitment. J Exp Med 193: 863–872, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Henry CB, Duling BR. TNF-α increases entry of macromolecules into luminal endothelial cell glycocalyx. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 279: H2815–H2823, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hoover RL, Briggs RT, Karnovsky MJ. The adhesive interaction between polymorphonuclear leukocytes and endothelial cells in vitro. Cell 14: 423–428, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hoover RL, Folger R, Haering WA, Ware BR, Karnovsky MJ. Adhesion of leukocytes to endothelium: roles of divalent cations, surface charge, chemotactic agents and substrate. J Cell Sci 45: 73–86, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. House SD, Lipowsky HH. Leukocyte-endothelium adhesion: microhemodynamics in mesentery of the cat. Microvasc Res 34: 363–379, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jung U, Norman KE, Scharffetter-Kochanek K, Beaudet AL, Ley K. Transit time of leukocytes rolling through venules controls cytokine-induced inflammatory cell recruitment in vivo. J Clin Invest 102: 1526–1533, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lagente V, Boichot E. Role of matrix metalloproteinases in the inflammatory process of respiratory diseases. J Mol Cell Cardiol 48: 440–444, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lambs L, Venturini M, Decock-Le Reverend B, Kozlowski H, Berthon G. Metal ion-tetracycline interactions in biological fluids. Part 8. Potentiometric and spectroscopic studies on the formation of Ca(II) and Mg(II) complexes with 4-dedimethylamino-tetracycline and 6-desoxy-6-demethyl-tetracycline. J Inorg Biochem 33: 193–210, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li Z, Li L, Zielke HR, Cheng L, Xiao R, Crow MT, Stetler-Stevenson WG, Froehlich J, Lakatta EG. Increased expression of 72-kd type IV collagenase (MMP-2) in human aortic atherosclerotic lesions. Am J Pathol 148: 121–128, 1996 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lipowsky HH, Haynes CA. Synthesis of an artificial glycocalyx for studies of leukocyte adhesion (Abstract). Proceedings of the 2005 Summer Bioengineering Conference 2005, Abstract 247851 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lipowsky HH, Scott DA, Cartmell JS. Leukocyte rolling velocity and its relation to leukocyte-endothelium adhesion and cell deformability. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 270: H1371–H1380, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lipowsky HH, Zweifach BW. Application of the “two-slit” photometric technique to the measurement of microvascular volumetric flow rates. Microvasc Res 15: 93–101, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mulivor AW, Lipowsky HH. Role of glycocalyx in leukocyte-endothelial cell adhesion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283: H1282–H1291, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mulivor AW, Lipowsky HH. Inflammation- and ischemia-induced shedding of venular glycocalyx. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 286: H1672–H1680, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mulivor AW, Lipowsky HH. Inhibition of glycan shedding and leukocyte-endothelial adhesion in postcapillary venules by suppression of matrixmetalloprotease activity with doxycycline. Microcirculation 1–10, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pries AR, Secomb TW, Gaehtgens P. The endothelial surface layer. Pflügers Arch 440: 653–666, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Reitsma S, Slaaf DW, Vink H, van Zandvoort MA, oude Egbrink MG. The endothelial glycocalyx: composition, functions, and visualization. Pflügers Arch 454: 345–359, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Spinale FG. Myocardial matrix remodeling and the matrix metalloproteinases: influence on cardiac form and function. Physiol Rev 87: 1285–1342, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Springer TA. Adhesion receptors of the immune system. Nature 346: 425–434, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stamenkovic I, Yu Q. Shedding light on proteolytic cleavage of CD44: the responsible sheddase and functional significance of shedding. J Invest Dermatol 129: 1321–1324, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Taraboletti G, D'Ascenzo S, Borsotti P, Giavazzi R, Pavan A, Dolo V. Shedding of the matrix metalloproteinases MMP-2, MMP-9, and MT1-MMP as membrane vesicle-associated components by endothelial cells. Am J Pathol 160: 673–80, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vink H, Duling BR. Identification of distinct luminal domains for macromolecules, erythrocytes, and leukocytes within mammalian capillaries. Circ Res 79: 581–589, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yu WH, Woessner JF., Jr Heparan sulfate proteoglycans as extracellular docking molecules for matrilysin (matrix metalloproteinase 7). J Biol Chem 275: 4183–91, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zweifach BW. Microcirculatory aspects of tissue injury. Ann NY Acad Sci 116: 831–838, 1964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]