Abstract

Endothelin-1 (ET-1) and activation of protein kinase C (PKC) have been implicated in alterations of myocyte function in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Changes in cellular Ca2+ handling and electrophysiological properties also occur in these states and may contribute to mechanical dysfunction and arrhythmias. While ET-1 or PKC stimulation induces cellular hypertrophy in cultured neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs), a system widely used in studies of hypertrophic signaling, there is little data about electrophysiological changes. Here we studied the effects of ET-1 (100 nM) or the PKC activator phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, 1 μM) on ionic currents in NRVMs. The acute effects of PMA or ET-1 (≤30 min) were small or insignificant. However, PMA or ET-1 exposure for 48–72 h increased cell capacitance by 100 or 25%, respectively, indicating cellular hypertrophy. ET-1 also slightly increased Ca2+ current density (T and L type). Na+/Ca2+ exchange current was increased by chronic pretreatment with either PMA or ET-1. In contrast, transient outward and delayed rectifier K+ currents were strongly downregulated by PMA or ET-1 pretreatment. Inward rectifier K+ current tended toward a decrease at larger negative potential, but time-independent outward K+ current was unaltered by either treatment. The enhanced inward and reduced outward currents also result in action potential prolongation after PMA or ET-1 pretreatment. We conclude that chronic PMA or ET-1 exposure in cultured NRVMs causes altered functional expression of cardiac ion currents, which mimic electrophysiological changes seen in whole animal and human hypertrophy and heart failure.

Keywords: neonatal cardiomyocytes, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, endothelin-1, hypertrophy, heart failure, neonatal rat ventricular myocytes

endothelin-1 (ET-1) and protein kinase C (PKC) activation have been implicated in altered cell signaling and gene expression in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure (2, 10, 11, 43, 45, 56). Neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs) in primary culture have been used extensively as a model system to explore the molecular and cellular events responsible for hormonally induced cellular hypertrophy and contractile protein gene expression. In addition, many of the features of pressure overload-induced myocyte hypertrophy observed in vivo can be simulated using these cultured cells. For instance, the exposure of NRVMs to various neurohumoral agents (e.g., adrenergic agonists, ET-1, or angiotensin II) produces myocyte hypertrophy and changes in gene expression characteristic of hypertrophic myocardium in vivo (22, 31, 44, 59, 62). Several of these growth-promoting stimuli lead to the activation of one or more of the isoenzymes of PKC (19, 20, 33, 43, 52, 70). The direct activation of Ca2+-dependent and novel PKC isoenzymes by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) in NRVMs also mimics aspects of the hypertrophic response to pressure overload in vivo. For example, PMA induces the expression of immediate early genes (15) and secondary response genes such as atrial natriuretic factor (58), β-myosin heavy chain (24, 54), and α-skeletal actin (29). PMA exposure also increases the overall cell protein expression (65) yet decreases the expression level and function of the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2a (SERCA2a) in NRVMs (8, 48, 50). The latter may be related to the downregulation of SERCA2 seen in many models of hypertrophy and heart failure (1, 51), contributing directly to mechanical cardiac dysfunction. Ca2+-dependent PKC isoenzymes (PKC-α, -β, and -γ) do not appear necessary for the induction of cardiac hypertrophy in response to pressure overload in vivo, but the PKC-α isoenzyme may negatively regulate sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ load and contractility, thereby affecting cardiac performance during the transition to heart failure (32). These data indicate that the PKC regulation of SERCA2 and Ca2+ handling is important for hypertrophy and heart failure in vivo, yet the effects of PKC activation on Ca2+ currents have not been examined in the NRVM model.

ET-1 expression is increased in animal models of cardiac hypertrophy, working in part through the activation of PKC (27, 45). ET-1 also potently stimulates NRVM hypertrophy (9, 61) and is partly dependent on the activation of a novel PKC-ϵ (21). Chronic ET-1 stimulation produces increased cell size and protein synthesis, increased transcription of myosin light chain-2, and atrial natriuretic factor, as well as enhanced sarcomeric assembly (14, 16, 36). Therefore, ET-1 and PKC activation are likely to be critical modulators of protein expression and phenotype in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure.

Cardiac hypertrophy and failure are also characterized by alterations in electrophysiological properties, notably decreased transient outward K+ current (Ito), reduced inward rectifier K+ current (IK1), modestly increased L-type and T-type Ca2+ currents (ICa,L and ICa,T, respectively), and enhanced Na+/Ca2+ exchange (NaCaX) (3, 6, 14, 39, 42, 46, 60, 64, 68). Indeed, these electrophysiological alterations may be important in triggered arrhythmias in heart failure. There is little information to date concerning how PKC activation alters ionic currents in NRVMs, although Gaughan et al. (17) found that chronic α-adrenergic activation in NRVMs altered the functional expression of Ca2+ current (ICa) and certain K+ currents. In addition, acute (<1 h) treatment of NRVMs with ET-1 was reported to activate reverse-mode NaCaX secondary to Na+/H+ exchange activation; however, the direct effects on NaCaX activity were not identified in response to ET-1 (14).

The aim of the present study is to characterize alterations in ionic current expression in NRVMs exposed to ET-1 and PMA. We measured the acute effects, which occur in 10–30 min (possibly because of the direct effects PKC-dependent phosphorylation), as well as the long-term effects induced by 48–72 h of exposure (referred to as “chronic treatment”) and then withdrawal during current measurements (which presumably reflect alterations in the functional expression of channel proteins or modulators). We measured ICa,L and ICa,T, NaCaX current (INa/Ca), Ito, IK1, and delayed rectifier K+ current (IKs). The acute effects were minimal, whereas chronic PMA and ET-1 exposure produced cellular hypertrophy and altered current densities in a manner consistent with reports in animal models of hypertrophy and heart failure.

METHODS

NRVM isolation and culture.

All animal protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Loyola University Chicago and University of California Davis. Animals used in these experiments were handled in accordance with National Institutes of Health's Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No 85-23, Revised 2010). NRVMs were isolated from the hearts of 1–3-day-old Sprague-Dawley rat pups via collagenase digestion as previously described (54). Dissociated cells were preplated for 1 h in serum-free PC-1 medium (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD) to selectively remove nonmuscle cells. Myocytes were then plated in PC-1 medium at a density of 400 or 1,600 cells/mm2 onto collagen-coated plastic 35- or 100-mm dishes or chamber slides and left undisturbed in a 5% CO2-95% room air incubator for 14–18 h. Unattached cells were removed by aspiration, and the attached cells were maintained in a solution of DMEM-medium 199 (4:1; GIBCO, Grand Island, NY) containing antibiotic/antimycotic solution. Ca2+-free and Mg2+-free Hanks' balanced salt solution, acid soluble calf skin collagen, and antibiotic/antimycotic solution were obtained from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO). PMA (1 μM ) or ET-1 (100 nM) was added at this time, and for parallel control plates medium was refreshed without added PMA or ET-1. Medium was changed daily, and all electrophysiological studies were 48–72 h after the PMA/ET-1 addition time.

For studies of acute exposure to PMA or ET-1, control cells were used and recordings were made before and after 10–30-min exposure to 1 μM PMA or 100 nM ET-1. For chronic studies, the cells exposed for 48–72 h to PMA or ET-1 (or not for control) were studied after the removal of PMA or ET-1 from the medium for 1 to 2 h. This was done to minimize the potentially complicating direct acute effects of PMA or ET-1, allowing an assessment of altered current as a consequence of altered protein expression.

Electrophysiological measurements.

All currents were recorded in whole cell ruptured patch voltage-clamp mode (Axopatch 200) at room temperature, except INa/Ca (measured at 35°C) with pipettes of 1–4-MΩ resistance with partial series resistance compensation (71). Ca2+ channel currents (L and T type) were measured with Na+ and K+ absent. The bathing solution contained (in mM) 140 tetraethylammonium (TEA)-Cl, 6 CsCl2, 2 MgCl2, 5 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose (pH 7.4), adjusted with TEA-OH at room temperature. The pipette solution contained (in mM) 125 CsCl, 10 Mg2+-ATP, 20 HEPES, 10 EGTA, 0.3 GTP, and 10 TEA-Cl (pH 7.4), adjusted with CsOH at room temperature. ICa,L was measured from a holding potential (Eh) = −50 mV, with depolarizing steps of 10 up to +60 mV (200-ms duration). ICa,T was measured from Eh = −100 mV with 2 μM nifedipine to block ICa,L with depolarizing steps of 10 up to +60 mV (200-ms duration).

INa/Ca was measured as the current blocked by Ni (5 mM) under conditions where most other currents were blocked. The bath solution contained (in mM) 140 NaCl, 6 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 5 HEPES, 10 glucose, 2 CaCl2, and 0.03 2,3-butanedione monoxime (pH 7.4) at 35°C, and the pipette solution contained (in mM) 14 NaCl, 55 Cs-methanesulfonate, 45 CsCl, 10 ATP-Tris, 0.3 GTP-Tris, 5 BAPTA, 5 Br2-BAPTA, 2.21 CaCl2, and 1.08 MgCl2 (pH 7.3) at 35°C. This solution is expected to have a free [Ca2+] = 100 nM, and additional experiments were also performed where free [Ca2+] in the pipette solution was increased to 1 μM.

K+ currents (Ito, IKs, and IK1) were measured using a bath solution containing (in mM) 138 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 0.3 CdCl2, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose (pH 7.4) with NaOH at room temperature. The pipette solution contained (in mM) 60 KCl, 70 K-aspartate, 10 Mg2+-ATP, 10 EGTA, 0.3 GTP, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.2) with KOH at room temperature. To record Ito, Eh was set at −70 mV with a 40-ms step to −60 mV, followed by depolarizing pulses from −30 to +120 mV for 300 ms (in 10-mV increments). The rapidly inactivating component was attributed to Ito (and was completely suppressed by 2 mM 4-aminopyridine), whereas the sustained component we refer to here is time-independent outward K+ current (ISS). To record IKs, Eh was −50 mV, followed by 10-mV depolarizing pulses from −20 to +80 mV for 3 s, returning to −25 mV for 4.5 s and finally to Eh. For IK1, Eh = −50 mV followed by 10 mV steps from −140 mV to 0 mV during 300 ms, returning to Eh afterward. Customized software was written to analyze the K+ currents.

Currents were expressed as current density by normalizing to cell capacitance, measured at the start of each experiment as described previously (71). Briefly, the capacitative transient due to 5-mV steps was measured and analyzed as Cm = τc/ΔVm[Io/1 − (I∞/Io)], where Cm is the membrane capacitance, τc is the time constant of the capacitative current relaxation, Io is the peak capacitative current determined by single exponential fit and extrapolation to the first sample point after the voltage step ΔVm, and I∞ is the amplitude of the steady-state current.

For action potential (AP) recordings, patch pipettes were backfilled with amphotericin (200 μg/ml). The pipette solution contained (in mM) 120 K+-glutamate, 25 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, and 10 N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-HEPES (pH 7.4) (KOH). The external solution contained (in mM) 138 NaCl, 4 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 0.33 NaH2PO4, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4) (NaOH).

Western blot analysis from cultured rat neonatal cardiomyocytes.

Adherent myocytes were collected with trypsin-EDTA and resuspended in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Myocytes were briefly homogenized with a tissue grinder, and protein concentrations were determined by BCA Protein Assay (ThermoScientific). Protein (30 μg/well) were run on a 4–20% gradient polyacrylamide gel at 80 V. Protein samples were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes overnight at 40 V. Membranes were blocked in 5% milk in TBS-Tween-20 for 1 h and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C with rocking. Primary antibodies for Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and GAPDH (Fitzgerald) were used at dilutions of 1:500 and 1:4,000, respectively. Horseradish peroxidase secondary antibodies (GE) were incubated at 1:4,000 for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were visualized with Super Signal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (ThermoScientific).

Compared values were judged different if unpaired Student's two-sided t-test or one-way ANOVA resulted in P ≤ 0.05. Values are expressed as means ± SE.

RESULTS

PMA and ET-1 treatment produce cellular hypertrophy.

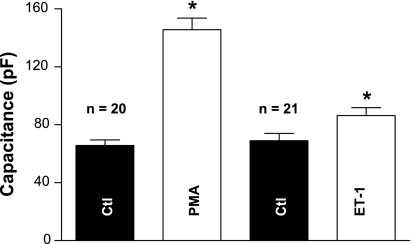

NRVMs have been used to model myocardial hypertrophy in response to neurohumoral agents, and optical methods indicated that ET-1 treatment for 24 h increases cell surface area (21). To further investigate the capacity of PKC activation and ET-1 treatment to induce hypertrophy in NRVMs, the cells were treated with PMA or ET-1 and the cell surface area was assessed by measuring cell Cm. Figure 1 shows that 48–72 h exposure to 1 μM PMA or 0.1 μM ET-1 led to a significant increase in cell capacitance compared with control cells cultured for the same period of time. For PMA, the capacitance increased from 66 ± 4 to 146 ± 8 pF (P < 0.05, n = 20 cells), and for ET-1, Cm increased from 69 ± 5 to 86 ± 5 pF (P < 0.05, n = 21 cells). This indicates that the cell surface area is increased by either treatment and is consistent with cellular hypertrophy caused by PKC activation in response to PMA exposure (59) or the hypertrophic effects of ET-1 (18).

Fig. 1.

Exposure of 1 μM PMA or 0.1 μM endothelin-1 (ET-1) for 48–72 h significantly increased cell membrane capacitance (Cm). PMA augmented Cm from 66 ± 4 to 146 ± 8 pF (*P < 0.05, n = 20). ET-1 increased Cm from 69 ± 5 to 86 ± 5 pF (*P < 0.05, n = 21) (4 preparations). Ctl, control; n, number of cells. *P < 0.05.

Effects of PMA and ET-1 on ICa.

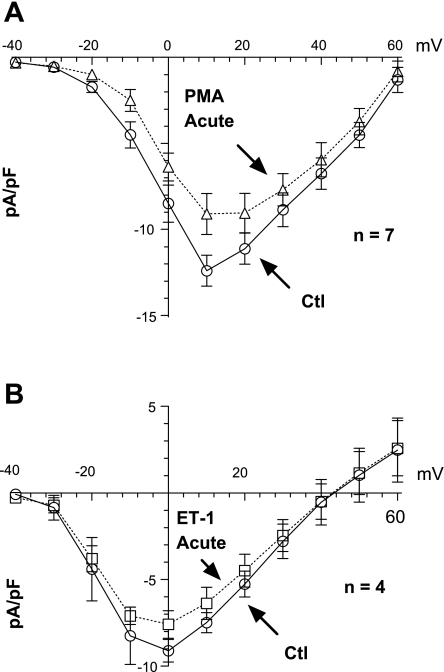

Because Ca2+ currents are increased during hypertrophy and heart failure (64, 68), we examined the effects of acute versus chronic PKC activation on ICa,L and ICa,T in NRVMs. Figure 2, A and B, shows that in control cells, an incubation for 30 min with PMA or ET-1 did not alter ICa,L appreciably. While mean ICa,L was slightly decreased, this was not significant at any potential. The stimulation of PKC by phorbol esters has discordant effects on ICa. Dösemeci et al. (13) reported an increase in this current, whereas Tseng and Boyden (63) saw a decrease and Walsh and Kass (67) observed no change at all. Our experiments show that chronic PMA treatment increased ICa, but this increased current almost exactly matched the increase in cell capacitance, such that ICa,L density was not significantly changed by PMA (supplemental Fig. 1; note: all supplemental material may be found posted with the online version of this article). Therefore, ICa,L expression is not increased in response to PMA treatment in NRVMs. Figure 3 shows that a chronic pretreatment with ET-1 produced a slight increase in both ICa,L and ICa,T. Neither the reversal potential, activation voltage, nor the voltage for maximum ICa was altered by ET-1 for either channel type. The increase in ICa,L and ICa,T induced by ET-1 was only significant at potentials where the currents are near their largest values. While the blockade of ICa,L with nifedipine minimizes the potential contamination of ICa,T by ICa,L (and >95% of ICa activated from Eh = −50 was blocked), such a complication would be most apparent at positive potentials. This was not the case; moreover, the effect of ET-1 on ICa,T was significant at −30 mV where there is almost no detectable ICa,L. Thus chronic ET-1 pretreatment may slightly enhance both ICa types in these myocytes. Although the diverse effects of ET-1 on ICa have been reported (12, 28, 30), the experimental conditions of those reports were of acute treatment. The chronic effects of ET-1 reported here are more consistent with the pathophysiological condition of heart failure.

Fig. 2.

Acute effects of PMA (A) and ET-1 (B) on L-type Ca2+ current (ICa,L). Incubation for 30 min of PMA or ET-1 did not affect peak ICa,L appreciably (3 preparations).

Fig. 3.

Chronic effects of ET-1 on ICa,L and T-type Ca2+ current (ICa,T). Representative traces from ICa,L (A) and ICa,T (B) during control and after pretreatment with 0.1 μM ET-1 for 48–72 h. C and D: current-voltage relationships for ICa,L and ICa,T, respectively, showing a significantly increased peak current at the highest values (3 preparations).

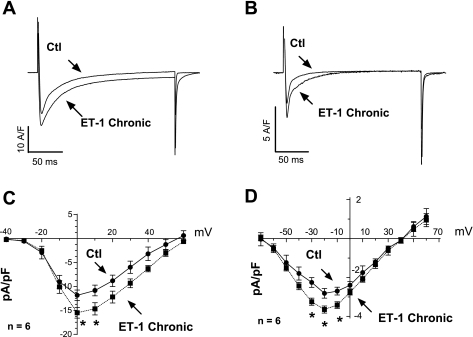

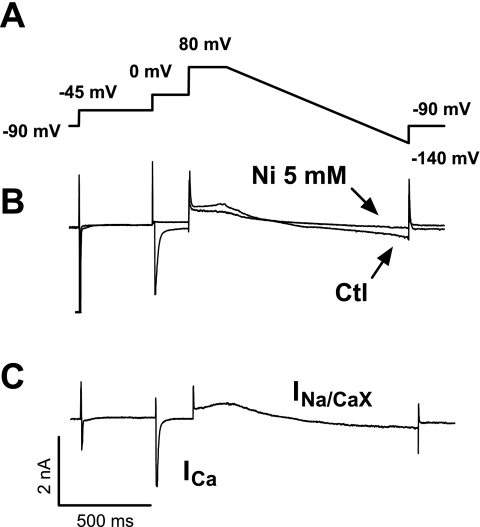

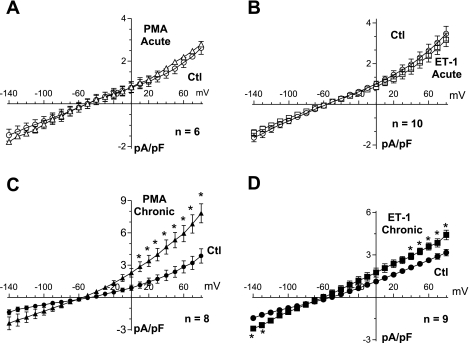

PMA and ET-1 increase INa/Ca expression but do not directly alter INa/Ca.

We investigated the chronic versus acute effects of PKC activation on the NaCaX activity in NRVMs directly by electrophysiological recording. Figure 4A shows the protocol used to measure INa/Ca. Starting at Eh = −90, a step to −45 mV activates and inactivates Na+ current. A subsequent step to 0 mV then activates and inactivates ICa. Finally, a ramp from +80 to −140 mV was used to assess the Ni-sensitive INa/Ca (Fig. 4B). This protocol was repeated in the presence or absence of 5 mM Ni. Figure 4C shows a record of INa/Ca after the subtraction of the two traces. An acute exposure of cells to either PMA (1 μM) or ET-1 (0.1 μM) for 10–30 min did not affect INa/Ca (Fig. 5, A and B). In contrast, pretreatment (48–72-h exposure) with either PMA or ET-1 significantly increased INa/Ca (Fig. 5, C and D). The reversal potential of INa/Ca was not altered, assuring that the intracellular Na+ and Ca2+ concentrations dictated by the pipette solution were the same for control and experimental cells. The ratio of PMA to control or ET-1 to control for INa/Ca, indicating the fold change in NaCaX activation, was consistent at nearly all membrane potential (Vm) values evaluated [2.16 ± 0.09 and 1.53 ± 0.07 for PMA (Fig. 5C) and ET-1 (Fig. 5D), respectively]. However, this difference was significant only at Vm values where the current was relatively large. To evaluate inward INa/Ca after PMA pretreatment, an additional series of experiments was performed at elevated [Ca2+]i (1 μM) to enhance INa/Ca amplitude (supplemental Fig. 2). This procedure shifted the reversal potential to a more positive Vm and confirmed the increased expression of inward INa/Ca. Furthermore, we measured the protein level expression for NaCaX and found a twofold increase for both ET-1 (2.26 ± 0.19, P ≤ 0.05) and PMA (2.34 ± 0.27, P ≤ 0.05) (supplemental Fig. 3). Therefore, the effects of PMA or ET-1 treatment on NRVMs mimic changes in NaCaX expression seen in the failing heart.

Fig. 4.

Measurement of Na+/Ca2+ exchange current (INa/Ca). A: voltage protocol. Starting at a holding potential of −90 mV follows a step to −45 mV to inactive Na+ current and then another step to 0 mV to inactive ICa,L. Finally, a ramp from +80 to −140 mV was used to assess the Ni-sensitive INa/Ca. B: raw traces obtained during control conditions and after application of 5 mM Ni. C: current record obtained after subtraction of the 2 traces. ICa, Ca2+ current.

Fig. 5.

Effect of PMA and ET-1 on INa/Ca. A: acute effect of 10–30-min exposure to 1 μM PMA. No significant changes on INa/Ca can be noticed. B: similarly, no effects can be seen by 10–30-min exposure to 0.1 μM ET-1. C: PMA pretreatment for 48–72 h induces a significant increase on INa/Ca. D: likewise, ET-1 pretreatment induces a significant (although smaller) increase on INa/Ca. In all cases, pipette [Ca2+] was 100 nM (4 preparations). Circles are control, triangles are PMA treatment, and squares are ET-1 treatment (white symbols, acute; and black symbols, chronic). *P < 0.05.

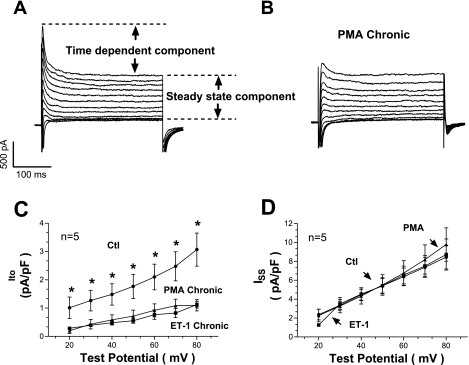

Pretreatment with PMA and ET-1 decreases Ito.

Chronic heart failure is associated with K+ channel misregulation, where decreased K+ current prevents repolarization and prolongs AP duration (APD). Therefore, we examined the outward K+ currents in response to PMA or ET-1 treatment. Cardiac myocytes were clamped from a holding voltage of −70 to −60 mV for 40 ms and then stimulated with 300-ms pulses from −30 to +120 mV before returning to the Eh. This protocol generated a transient current (Ito), followed by inactivation to a sustained outward level (ISS) at the end of the pulse (Fig. 6A). An acute exposure to PMA (or ET-1) did not alter either component of this current appreciably (supplemental Fig. 4), a chronic exposure of PMA or ET-1 reduced the Ito component but not the ISS (Fig. 6, B–D). Thus PMA and ET-1 downregulated the expression of Ito but had no effect on ISS. Decreased Ito is expected to reduce the amount of early repolarization of the AP and prolong APD. Moreover, the downregulation of Ito is a hallmark of cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure (5, 47) and can contribute to hypertrophy as well (25).

Fig. 6.

Effects of PMA and ET-1 on transient outward K+ current (Ito). A: raw traces obtained after applying a voltage protocol in control conditions. Two components can be identified: a time-dependent component right after the stimulus and a steady-state component at the end of the pulse. B: raw traces obtained after pretreatment with PMA. C: transient component is severely reduced with PMA or ET-1 treatment. D: steady-state component, conversely, is unaffected by either PMA or ET-1 (3 preparations). ISS, time-dependent outward K+ current. *P < 0.05.

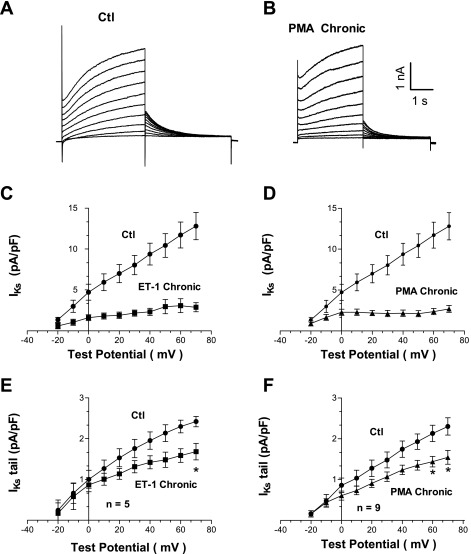

Chronic PMA and ET-1 treatment decreases IKs.

Adult rat ventricular myocytes do not normally express the delayed rectifier K+ channels, either IKs or IKr, that are the major repolarizing currents in large mammals. However, in this cultured NRVM model, we detect a slowly activating K+ current that resembles classical IKs. Figure 7A shows IKs assessment in NRVMs by 4-s-long voltage-clamp pulse protocol (55). Both the slowly developing outward current (Fig. 7, C and D) and tail currents at the end of the 4-s pulse (Fig. 7, E and F) were analyzed. An acute application of PMA or ET-1 did not produce substantive changes in IKs (supplemental Fig. 5). In contrast, treatment for 48–72 h with PMA or ET-1 decreased IKs (Figs. 7, C and D). Raw traces from PMA-treated cells are illustrated in Fig. 7B. Tail K+ currents were also depressed by either PMA or ET-1 pretreatment. Figure 7, bottom, shows normalized tail currents from cells pretreated with ET-1 (Fig. 7E) and PMA (Fig. 7F). Consequently, our experiments with NRVMs suggest that there is IKs functionally expressed, and chronic exposure to hypertrophic agonists reduces its functional expression, consistent with prolonged APD seen in larger mammals during hypertrophy and heart failure.

Fig. 7.

Chronic effect of PMA and ET-1 on delayed rectifier K+ current (IKs). A: raw current traces obtained under control conditions. B: effect of pretreating neonatal cells for 48–72 h with 1 μM PMA. C: slowly activating component of IKs is significantly depressed by 0.1 μM ET-1. D: likewise, PMA decreased significantly IKs. E: tail currents are also reduced by ET-1. F: similar effect on tail currents is obtained by pretreatment with PMA (4 preparations). *P < 0.05.

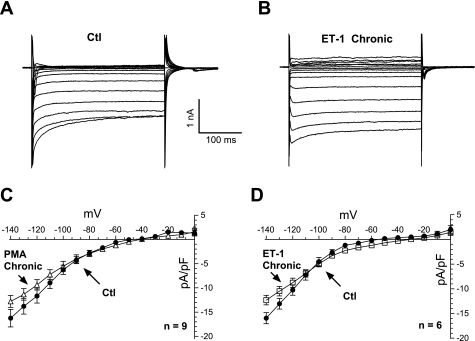

IK1 is borderline reduced by PMA and ET-1 only at higher negative potentials.

Inward rectifying K+ current (IK1) is diminished in adult heart failure (47) contributing to (among other mechanisms) the onset of arrhythmias. The strong IK1 that is central in stabilizing the resting Vm in ventricular myocytes was assessed in NRVMs using step pulses (duration, 300 ms) from −140 to 0 mV. Raw control traces are shown in Fig. 8A. An acute application of PMA had no effect on IK1 in NRVMs (supplemental Fig. 6). A chronic pretreatment with ET-1 (and PMA) produced a tendency for reduced IK1 at the more negative Vm (Fig. 8B), but this trend did not reach statistical significance; during the physiological voltage range (0 to −100 mV), no changes were observed.

Fig. 8.

Chronic effects of PMA and ET-1 on inward rectifier K+ current (IK1). A: raw data obtained under control conditions. B: current traces obtained after pretreatment for 48–72 h with 0.1 μM ET-1. C: similar pretreatment with 1 μM PMA produced a slight increase (not statistically significant) on IK1 at more negative potentials. D: similar tendency on IK1 is observed with ET-1 (4 preparations).

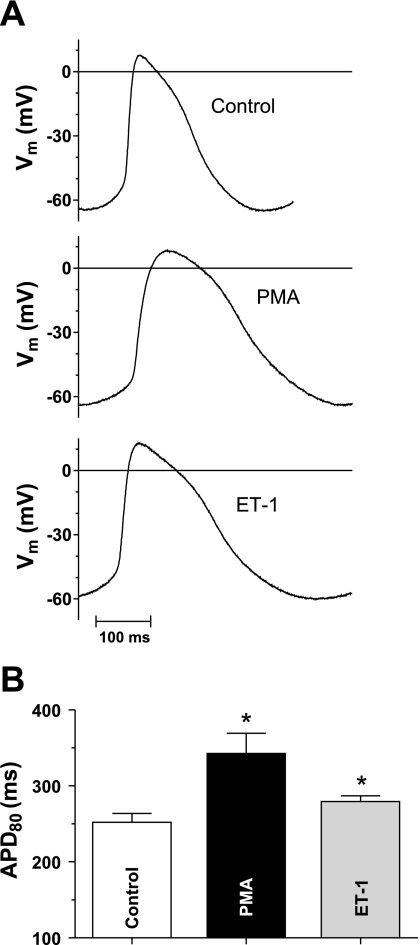

APD is increased by PMA and ET-1.

The above effects of 48–72-h PMA or ET-1 exposure to increase predominantly inward currents (ICa and INa/Ca) and reduce outward currents (Ito and IKs) would be expected to prolong APD. Figure 9A shows AP traces with and without PMA and ET-1 pretreatment. Mean data (Fig. 9B) show that a significant prolongation on APD at 80% repolarization (APD80) is observable for both treatments (control APD80 = 252 ± 11.7, PMA APD80 = 342 ± 26.9, and ET-1 APD80 = 279 ± 7.5 ms; P ≤ 0.05). Noticeably, the resting Vm did not change (control, −64.7 ± 2.6; PMA, −63.4 ± 2.5; and ET-1, −61.3 ± 1.4 mV; not significant), which is consistent with the lack of significant changes in IK1 within the physiological voltage range.

Fig. 9.

Chronic effects of PMA and ET-1 on action potential duration (APD). A: raw action potential measurements for control, PMA, and ET-1 pretreatment. B: mean APD at 80% repolarization (APD80) values for 5 cells each from 2 preparations. Control APD80 = 252 ± 11.7, PMA APD80 = 342 ± 26.9, and ET-1 APD80 = 279 ± 7.5 ms (*P < 0.05 vs. control). Vm, membrane potential.

DISCUSSION

Here we characterized PMA and ET-1 effects (both acute and chronic) on the main ionic currents in NRVM APs and excitation-contraction coupling. PMA is a strong direct PKC activator, whereas ET-1 activates Gq-coupled receptors and activates both PKC and 1,4,5-inositol trisphosphate (IP3) production. Both are known to induce hypertrophy in NRVMs, and these cultured myocytes have been used in hundreds of studies to elucidate signaling pathways and alterations in the expression of key proteins in cardiac myocytes, typically upon chronic agonist activation. However, there has been relatively little characterization of ionic currents in NRVMs, especially in response to hypertrophic agonists. Acute exposures (30 min) sufficient to activate both PKC and IP3 production did not significantly alter Cm or ion channel activity, suggesting that the acute regulation of these currents by PKC or IP3-dependent pathways is minimal. On the other hand, a 48–72-h exposure to PMA and ET-1 and washout before measurement resulted in substantial cellular hypertrophy and changes in the current density of many ionic currents. Because the acute effects were minimal, we infer that these chronic changes in current density are the result of the altered expression levels of either the channel proteins themselves or modulators (disproportionate to the degree of cellular hypertrophy). The cellular hypertrophy measured here as cell capacitance agrees with previous reports of the hypertrophic effects of PKC activators and is consistent with a PKC-dependent increase in cell surface area observed optically and by protein expression studies in response to ET-1 treatment of NRVMs (50).

ICa,L density was not significantly altered by chronic PMA treatment, but it should be appreciated that the cell surface area was increased by ∼100% (Fig. 1). This means that there was an upregulation of ICa,L functional expression that kept pace almost perfectly with the cellular hypertrophy. In contrast, ET-1 pretreatment produced a modest increase in both ICa,L and ICa,T. It is possible that the exaggerated functional upregulation of ICa,L and ICa,T is not PKC dependent (since PMA is such a strong PKC activator). ET-1 also causes IP3 production, which could induce Ca2+-dependent changes in transcription. Indeed, IP3 and Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent signaling can lead to an altered transcriptional regulation via calcineurin-NFAT and CaMKII-HDAC pathways (34, 69). In adult hearts, hypertrophy and heart failure have been associated with the enhanced density of ICa,T (41) and either unaltered or slightly increased ICa,L (7, 38, 46, 47).

It is well established that NaCaX plays a major role in myocyte Ca2+ efflux (4). There are reports suggesting an acute PKC-dependent regulation of NaCaX (26, 57), but we did not detect the acute effects of PMA in NRVMs. However, a chronic treatment with ET-1 or PMA increased INa/Ca density. Again, this indicates that NaCaX is upregulated above and beyond the overall cellular hypertrophy. Such increases in NaCaX density are also seen in adult myocytes from hypertrophied (37) and failing hearts (46). Furthermore, computer models show how this increased NaCaX can be arrhythmogenic (49). It is possible that ET-1/PMA and hypertrophic signaling increase NaCaX expression, which is beneficial initially but becomes maladaptive in the transition from hypertrophy to heart failure (35).

Ito was dramatically reduced by chronic, but unaltered by acute, PMA and ET-1 exposure. Note that this reduction exceeds the extent of cellular hypertrophy (Fig. 6C), suggesting that there is a net decrease in the rate of Ito functional expression, not simply a dilution of the same number of Ito channels into a bigger cell. Notably ISS density was unaltered by chronic PMA or ET-1 exposure, consistent with the idea that ISS expression increases on pace with cellular hypertrophy (so something other than PKC or IP3 dominates control of this constancy of current density). Ito exhibits rapid activation and inactivation and is responsible for the early repolarization phase of the cardiac AP and, in adult rat and mouse myocytes, is the predominant repolarizing current. Ito reduction is a very common finding in both ventricular hypertrophy and heart failure (3, 6, 40, 47), and reduced Ito can contribute to AP prolongation (especially in rat and mouse). Notably, the early repolarization driven by Ito can also exert critical control over myocyte Ca2+ transients by influencing the driving force for ICa (53).

While IKs is not usually demonstrable in adult rat or mouse hearts, we observed measurable IKs in NRVMs, which is reduced by chronic exposure to hypertrophic agonists. Our findings that ET-1 or PMA treatment decrease IKs are consistent with the findings of Volders et al. (66) of decreased IKs in dogs with hypertrophy induced by atrioventricular blockade. Reduced IKs enhances APD and favors the occurrence of early afterdepolarizations. In the theoretical model of ventricular cardiac myocytes implemented by LabHEART, a 50% decrease in IKs increased the AP by 12% (APD90 = 202 ms control vs. 181-ms IKs reduced) (49). Thus our results with NRVMs concur with theoretical and in vivo animal models of hypertrophy.

Notably, the net effects of PMA and ET-1 were to increase the currents that are predominantly inward currents during the AP (ICa and NaCaX) and also decrease repolarizing K+ currents (Ito and IKs). These are qualitatively like many reports with respect to these currents in adult hypertrophy and heart failure and would all tend to prolong APD (also typical in adult hypertrophy and heart failure). Indeed, we measured AP prolongation in myocytes exposed to PMA or ET-1 for 48–72 h. By and large, PMA and ET-1 produced similar effects with the exception of ICa,L, which would be consistent with PKC activation as the most likely candidate in driving most of the altered functional expression. Our results provide a useful survey of overall acute and chronic effects of ET-1 and PMA on NRVM currents, and this should be a valuable complement to the extensive biochemical and morphological work in this cellular model. However, this is only a starting point for more detailed mechanistic studies of each current to better understand the details of the signaling pathways, transcriptional regulation, and specific channel subunits involved in these changes.

NRVMs are a powerful cellular model that has been a workhorse for studies of cardiac cell signaling involved in hypertrophic remodeling of the heart. However, little was known about the fundamental changes in ion currents known to be associated with adult hypertrophy and heart failure in the setting of hypertrophic stimuli in NRVMs. We found little acute effect of PMA or ET-1 exposure on ICa, NaCaX, or K+ currents in NRVMs. In contrast, chronic exposure to ET-1 (and for the most part PMA) produces changes in current levels that are comparable (at least in direction) with numerous reports from adult hypertrophy and heart failure models. Namely, there was a modest enhancement of ICa,L and ICa,T, a greater increase in NaCaX, and a reduction in several K+ currents (Ito and IKs) with a matching increase in APD. While this system and our data here are not a substitute for adult myocyte studies of hypertrophy, this characterization provides a valuable electrophysiological context for signaling studies in NRVMs.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants R37-HL-30077 and P01-HL-80101.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Robert Rigor for critical reading of the manuscript and Dr. Kenneth Ginsburg for valuable suggestions.

REFERENCES

- 1. Arai M, Alpert NR, MacLennan DH, Barton P, Periasamy M. Alterations in sarcoplasmic reticulum gene expression in human heart failure. A possible mechanism for alterations in systolic and diastolic properties of the failing myocardium. Circ Res 72: 463–469, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Belin RJ, Sumandea MP, Allen EJ, Schoenfelt K, Wang H, Solaro RJ, de Tombe PP. Augmented protein kinase C-alpha-induced myofilament protein phosphorylation contributes to myofilament dysfunction in experimental congestive heart failure. Circ Res 101: 195–204, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Benitah JP, Gomez AM, Bailly P, Da Ponte JP, Berson G, Delgado C, Lorente P. Heterogeneity of the early outward current in ventricular cells isolated from normal and hypertrophied rat hearts. J Physiol 469: 111–138, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bers DM. Calcium cycling and signaling in cardiac myocytes. Annu Rev Physiol 70: 23–49, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bers DM. Excitation Contraction Coupling and Cardiac Contractile Force. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beuckelmann DJ, Nabauer M, Erdmann E. Alterations of K+ currents in isolated human ventricular myocytes from patients with terminal heart failure. Circ Res 73: 379–385, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beuckelmann DJ, Nabauer M, Erdmann E. Characteristics of calcium-current in isolated human ventricular myocytes from patients with terminal heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol 23: 929–937, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Blum JL, Samarel AM, Mestril R. Phosphorylation and binding of AUF1 to the 3′-untranslated region of cardiomyocyte SERCA2a mRNA. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 289: H2543–H2550, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bogoyevitch MA, Sugden PH. The role of protein kinases in adaptational growth of the heart. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 28: 1–12, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bowling N, Walsh RA, Song G, Estridge T, Sandusky GE, Fouts RL, Mintze K, Pickard T, Roden R, Bristow MR, Sabbah HN, Mizrahi JL, Gromo G, King GL, Vlahos CJ. Increased protein kinase C activity and expression of Ca2+-sensitive isoforms in the failing human heart. Circulation 99: 384–391, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bowman JC, Steinberg SF, Jiang T, Geenen DL, Fishman GI, Buttrick PM. Expression of protein kinase C beta in the heart causes hypertrophy in adult mice and sudden death in neonates. J Clin Invest 100: 2189–2195, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cheng TH, Chang CY, Wei J, Lin CI. Effects of endothelin 1 on calcium and sodium currents in isolated human cardiac myocytes. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 73: 1774–1783, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dösemeci A, Dhallan RS, Cohen NM, Lederer WJ, Rogers TB. Phorbol ester increases calcium current and simulates the effects of angiotensin II on cultured neonatal rat heart myocytes. Circ Res 62: 347–357, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dulce RA, Hurtado C, Ennis IL, Garciarena CD, Alvarez MC, Caldiz C, Pierce GN, Portiansky EL, Chiappe de Cingolani GE, Camilion de Hurtado MC. Endothelin-1 induced hypertrophic effect in neonatal rat cardiomyocytes: involvement of Na+/H+ and Na+/Ca2+ exchangers. J Mol Cell Cardiol 41: 807–815, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dunnmon PM, Iwaki K, Henderson SA, Sen A, Chien KR. Phorbol esters induce immediate-early genes and activate cardiac gene transcription in neonatal rat myocardial cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol 22: 901–910, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fukuda Y, Hirata Y, Taketani S, Kojima T, Oikawa S, Nakazato H, Kobayashi Y. Endothelin stimulates accumulations of cellular atrial natriuretic peptide and its messenger RNA in rat cardiocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 164: 1431–1436, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gaughan JP, Hefner CA, Houser SR. Electrophysiological properties of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes with alpha1-adrenergic-induced hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 275: H577–H590, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Giannessi D, Del Ry S, Vitale RL. The role of endothelins and their receptors in heart failure. Pharmacol Res 43: 111–126, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hartman TJ, Martin JL, Solaro RJ, Samarel AM, Russell B. CapZ dynamics are altered by endothelin-1 and phenylephrine via PIP2- and PKC-dependent mechanisms. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 296: C1034–C1039, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Heidkamp MC, Bayer AL, Scully BT, Eble DM, Samarel AM. Activation of focal adhesion kinase by protein kinase C epsilon in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H1684–H1696, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Heidkamp MC, Iyengar R, Szotek EL, Cribbs LL, Samarel AM. Protein kinase Cepsilon-dependent MARCKS phosphorylation in neonatal and adult rat ventricular myocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 42: 422–431, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ito H, Hirata Y, Hiroe M, Tsujino M, Adachi S, Takamoto T, Nitta M, Taniguchi K, Marumo F. Endothelin-1 induces hypertrophy with enhanced expression of muscle-specific genes in cultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. Circ Res 69: 209–215, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kaab S, Nuss HB, Chiamvimonvat N, O'Rourke B, Pak PH, Kass DA, Marban E, Tomaselli GF. Ionic mechanism of action potential prolongation in ventricular myocytes from dogs with pacing-induced heart failure. Circ Res 78: 262–273, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kariya K, Karns LR, Simpson PC. Expression of a constitutively activated mutant of the beta-isozyme of protein kinase C in cardiac myocytes stimulates the promoter of the beta-myosin heavy chain isogene. J Biol Chem 266: 10023–10026, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kassiri Z, Zobel C, Nguyen TT, Molkentin JD, Backx PH. Reduction of Ito causes hypertrophy in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. Circ Res 90: 578–585, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Katanosaka Y, Kim B, Wakabayashi S, Matsuoka S, Shigekawa M. Phosphorylation of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger in TAB-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Ann NY Acad Sci 1099: 373–376, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kedzierski RM, Yanagisawa M. Endothelin system: the double-edged sword in health and disease. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 41: 851–876, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kelso E, Spiers P, McDermott B, Scholfield N, Silke B. Dual effects of endothelin-1 on the L-type Ca2+ current in ventricular cardiomyocytes. Eur J Pharmacol 308: 351–355, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Komuro I, Yazaki Y. Molecular mechanism of cardiac hypertrophy and failure. Clin Sci (Lond) 87: 115–116, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lauer MR, Gunn MD, Clusin WT. Endothelin activates voltage-dependent Ca2+ current by a G protein-dependent mechanism in rabbit cardiac myocytes. J Physiol 448: 729–747, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee RT, Bloch KD, Pfeffer JM, Pfeffer MA, Neer EJ, Seidman CE. Atrial natriuretic factor gene expression in ventricles of rats with spontaneous biventricular hypertrophy. J Clin Invest 81: 431–434, 1988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu Q, Chen X, Macdonnell SM, Kranias EG, Lorenz JN, Leitges M, Houser SR, Molkentin JD. Protein kinase Cα, but not PKCβ or PKCγ, regulates contractility and heart failure susceptibility: implications for ruboxistaurin as a novel therapeutic approach. Circ Res 105: 194–200, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Long CS, Kariya K, Karns L, Simpson PC. Sympathetic modulation of the cardiac myocyte phenotype: studies with a cell-culture model of myocardial hypertrophy. Basic Res Cardiol 87, Suppl 2: 19–31, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. MacDonnell SM, Weisser-Thomas J, Kubo H, Hanscome M, Liu Q, Jaleel N, Berretta R, Chen X, Brown JH, Sabri AK, Molkentin JD, Houser SR. CaMKII negatively regulates calcineurin-NFAT signaling in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res 105: 316–325, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. MacLellan WR, Schneider MD. Success in failure: modeling cardiac decompensation in transgenic mice. Circulation 97: 1433–1435, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McDonough PM, Stella SL, Glembotski CC. Involvement of cytoplasmic calcium and protein kinases in the regulation of atrial natriuretic factor secretion by contraction rate and endothelin. J Biol Chem 269: 9466–9472, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Menick DR, Renaud L, Buchholz A, Muller JG, Zhou H, Kappler CS, Kubalak SW, Conway SJ, Xu L. Regulation of Ncx1 gene expression in the normal and hypertrophic heart. Ann NY Acad Sci 1099: 195–203, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mewes T, Ravens U. L-type calcium currents of human myocytes from ventricle of non-failing and failing hearts and from atrium. J Mol Cell Cardiol 26: 1307–1320, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nabauer M, Beuckelmann DJ, Erdmann E. Characteristics of transient outward current in human ventricular myocytes from patients with terminal heart failure. Circ Res 73: 386–394, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nabauer M, Kaab S. Potassium channel down-regulation in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 37: 324–334, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nakayama H, Bodi I, Correll RN, Chen X, Lorenz J, Houser SR, Robbins J, Schwartz A, Molkentin JD. alpha1G-dependent T-type Ca2+ current antagonizes cardiac hypertrophy through a NOS3-dependent mechanism in mice. J Clin Invest 119: 3787–3796, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Owada A, Tomita K, Terada Y, Sakamoto H, Nonoguchi H, Marumo F. Endothelin (ET)-3 stimulates cyclic guanosine 3′,5′-monophosphate production via ETB receptor by producing nitric oxide in isolated rat glomerulus, and in cultured rat mesangial cells. J Clin Invest 93: 556–563, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Palaniyandi SS, Sun L, Ferreira JC, Mochly-Rosen D. Protein kinase C in heart failure: a therapeutic target? Cardiovasc Res 82: 229–239, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Parker TG, Packer SE, Schneider MD. Peptide growth factors can provoke “fetal” contractile protein gene expression in rat cardiac myocytes. J Clin Invest 85: 507–514, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pieske B, Beyermann B, Breu V, Loffler BM, Schlotthauer K, Maier LS, Schmidt-Schweda S, Just H, Hasenfuss G. Functional effects of endothelin and regulation of endothelin receptors in isolated human nonfailing and failing myocardium. Circulation 99: 1802–1809, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pogwizd SM, Qi M, Yuan W, Samarel AM, Bers DM. Upregulation of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger expression and function in an arrhythmogenic rabbit model of heart failure. Circ Res 85: 1009–1019, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pogwizd SM, Schlotthauer K, Li L, Yuan W, Bers DM. Arrhythmogenesis and contractile dysfunction in heart failure: roles of sodium-calcium exchange, inward rectifier potassium current, and residual beta-adrenergic responsiveness. Circ Res 88: 1159–1167, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Porter MJ, Heidkamp MC, Scully BT, Patel N, Martin JL, Samarel AM. Isoenzyme-selective regulation of SERCA2 gene expression by protein kinase C in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 285: C39–C47, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Puglisi JL, Bers DM. LabHEART: an interactive computer model of rabbit ventricular myocyte ion channels and Ca transport. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 281: C2049–C2060, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Qi M, Bassani JW, Bers DM, Samarel AM. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate alters SR Ca2+-ATPase gene expression in cultured neonatal rat heart cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 271: H1031–H1039, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Qi M, Shannon TR, Euler DE, Bers DM, Samarel AM. Downregulation of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase during progression of left ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 272: H2416–H2424, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sadoshima J, Izumo S. Signal transduction pathways of angiotensin II–induced c-fos gene expression in cardiac myocytes in vitro. Roles of phospholipid-derived second messengers. Circ Res 73: 424–438, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sah R, Ramirez RJ, Oudit GY, Gidrewicz D, Trivieri MG, Zobel C, Backx PH. Regulation of cardiac excitation-contraction coupling by action potential repolarization: role of the transient outward potassium current (Ito). J Physiol 546: 5–18, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Samarel AM, Engelmann GL. Contractile activity modulates myosin heavy chain-β expression in neonatal rat heart cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 261: H1067–H1077, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sanguinetti MC, Jurkiewicz NK. Two components of cardiac delayed rectifier K+ current. Differential sensitivity to block by class III antiarrhythmic agents. J Gen Physiol 96: 195–215, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sentex E, Wang X, Liu X, Lukas A, Dhalla NS. Expression of protein kinase C isoforms in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure due to volume overload. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 84: 227–238, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shigekawa M, Katanosaka Y, Wakabayashi S. Regulation of the cardiac Na+/Ca2+ exchanger by calcineurin and protein kinase C. Ann NY Acad Sci 1099: 53–63, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Shubeita HE, Martinson EA, Van Bilsen M, Chien KR, Brown JH. Transcriptional activation of the cardiac myosin light chain 2 and atrial natriuretic factor genes by protein kinase C in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 1305–1309, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Simpson PC. Beta-protein kinase C and hypertrophic signaling in human heart failure. Circulation 99: 334–337, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Studer R, Reinecke H, Bilger J, Eschenhagen T, Bohm M, Hasenfuss G, Just H, Holtz J, Drexler H. Gene expression of the cardiac Na+-Ca2+ exchanger in end-stage human heart failure. Circ Res 75: 443–453, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Sugden PH. An overview of endothelin signaling in the cardiac myocyte. J Mol Cell Cardiol 35: 871–886, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Takeishi Y, Goto K, Kubota I. Role of diacylglycerol kinase in cellular regulatory processes: a new regulator for cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Pharmacol Ther 115: 352–359, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Tseng GN, Boyden PA. Different effects of intracellular Ca and protein kinase C on cardiac T and L Ca currents. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 261: H364–H379, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Vassort G, Talavera K, Alvarez JL. Role of T-type Ca2+ channels in the heart. Cell Calcium 40: 205–220, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Vijayan K, Szotek EL, Martin JL, Samarel AM. Protein kinase C-α-induced hypertrophy of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H2777–H2789, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Volders PG, Sipido KR, Vos MA, Spatjens RL, Leunissen JD, Carmeliet E, Wellens HJ. Downregulation of delayed rectifier K+ currents in dogs with chronic complete atrioventricular block and acquired torsades de pointes. Circulation 100: 2455–2461, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Walsh KB, Kass RS. Regulation of a heart potassium channel by protein kinase A and C. Science 242: 67–69, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wang Z, Kutschke W, Richardson KE, Karimi M, Hill JA. Electrical remodeling in pressure-overload cardiac hypertrophy: role of calcineurin. Circulation 104: 1657–1663, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wu X, Zhang T, Bossuyt J, Li X, McKinsey TA, Dedman JR, Olson EN, Chen J, Brown JH, Bers DM. Local InsP3-dependent perinuclear Ca2+ signaling in cardiac myocyte excitation-transcription coupling. J Clin Invest 116: 675–682, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Yamazaki T, Komuro I, Kudoh S, Zou Y, Shiojima I, Hiroi Y, Mizuno T, Maemura K, Kurihara H, Aikawa R, Takano H, Yazaki Y. Endothelin-1 is involved in mechanical stress-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Biol Chem 271: 3221–3228, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yuan W, Ginsburg KS, Bers DM: Comparison of sarcolemmal Ca2+ channel current in rabbit and rat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol 493: 733–746, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.