Abstract

Objective

To estimate the shortage of mental health professionals in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Methods

We used data from the World Health Organization’s Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems (WHO-AIMS) from 58 LMICs, country-specific information on the burden of various mental disorders and a hypothetical core service delivery package to estimate how many psychiatrists, nurses and psychosocial care providers would be needed to provide mental health care to the total population of the countries studied. We focused on the following eight problems, to which WHO has attached priority: depression, schizophrenia, psychoses other than schizophrenia, suicide, epilepsy, dementia, disorders related to the use of alcohol and illicit drugs, and paediatric mental disorders.

Findings

All low-income countries and 59% of the middle-income countries in our sample were found to have far fewer professionals than they need to deliver a core set of mental health interventions. The 58 LMICs sampled would need to increase their total mental health workforce by 239 000 full-time equivalent professionals to address the current shortage.

Conclusion

Country-specific policies are needed to overcome the large shortage of mental health-care staff and services throughout LMICs.

ملخص

الغرض: تقدير نقص مهنييّ الصحة النفسية في البلدان المنخفضة والمتوسطة الدخل.

الطرائق: استخدم الباحثون معطيات من أداة تقييم منظمة الصحة العالمية لنظم الصحة النفسية في 58 بلداً من البلدان المنخفضة والمتوسطة الدخل، والمعلومات القطرية المعنية والمتعلقة بالعبء الناجم عن مختلف الاضطرابات النفسية، وحزمة إيتاء الخدمات الأساسية المفترضة ، وذلك بهدف لتقدير عدد الأطباء النفسيين، والممرضين ومقدمي الرعاية النفسية اللازمين لتقديم رعاية صحية نفسية لمجمل سكان البلدان محل الدراسة. وركّز الباحثون على المشاكل الثمانية التالية التي أولتها منظمة الصحة العالمية الأولوية: الاكتئاب، والفُصام، والذُهانات، وهي غير الفصام، والانتحار، والصرع، والخرف، والاضطرابات المصاحبة لتعاطي الكحوليات والأدوية غير المشروعة، والاضطرابات النفسية لدى الأطفال.

النتائج: جميع البلدان المنخفضة الدخل و59% من البلدان المتوسطة الدخل التي شملها البحث كان لديها عدد من المهنيين النفسيين أقل بكثير من العدد المطلوب لتقديم المجموعة الأساسية من تدخلات الصحة النفسية. وتحتاج البلدان الثمانية والخمسون التي اختيرت في العينة إلى زيادة العدد الإجمالي للقوى العاملة لديها في مجال الصحة النفسية بمقدار 239 ألفاً من المهنيين الذينن يعملون بدوام كامل للتصدى لهذا النقص الحالي.

الاستنتاج: هناك حاجة إلى سياسات قطرية معنية للتغلب على النقص الهائل في عدد العاملين في خدمات ورعاية الصحة النفسية في جميع البلدان المنخفضة والمتوسطة الدخل.

Résumé

Objectif

Estimer le manque de professionnels de la santé mentale dans les pays à revenu faible ou intermédiaire (PRFI).

Méthodes

Nous avons utilisé les données fournies par l’instrument d’évaluation des systèmes de santé mentale de l’Organisation mondiale de la Santé (OMS-AIMS) et relatives à 58 PRFI, les informations spécifique aux pays sur la charge des différents troubles mentaux, ainsi qu’une hypothétique offre groupée de prestations de services essentiels et ce, afin d’estimer le nombre de psychiatres, d’infirmiers et de spécialistes psychosociaux qui serait nécessaire pour fournir des soins de santé mentale à l’ensemble de la population des pays étudiés. Nous avons mis l’accent sur les huit problèmes suivants, que l’OMS tient pour prioritaires: dépression, schizophrénie, psychoses autres que la schizophrénie, suicide, épilepsie, démence, troubles liés à l’alcoolisme et aux substances illicites et troubles mentaux infantiles.

Résultats

Tous les pays à revenu faible et 59% des pays à revenu moyen de notre échantillon disposaient d’un nombre de professionnels largement inférieur par rapport à leurs besoins en prestations de santé mentale essentielles. Les 58 PRFI de l’échantillon devraient créer 239 000 emplois supplémentaires à temps complet dans le secteur de la santé mentale afin de parer au manque actuel.

Conclusion

Des politiques inhérentes à chaque pays sont nécessaires pour surmonter le vaste manque de personnel et de services de santé mentale dans les PRFI.

Resumen

Objetivo

Calcular la escasez de profesionales psiquiátricos en los países de ingresos medios y bajos (PIMB).

Métodos

Para calcular el número de psiquiatras, personal de enfermería y psicólogos que serían necesarios para proporcionar asistencia psiquiátrica al total de la población de los países estudiados, utilizamos los datos del Instrumento de Evaluación de los Sistemas de Salud Mental de la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS-AIMS) de 58 PIMB, la información específica de cada país sobre la carga de los distintos trastornos mentales y la prestación hipotética de servicios básicos. Nos centramos en los ocho problemas siguientes, a los que la OMS ha otorgado prioridad: depresión, esquizofrenia y otras psicosis, suicidio, epilepsia, demencia, trastornos asociados al abuso del alcohol y las drogas ilegales, así como los trastornos mentales pediátricos.

Resultados

Todos los países de ingresos bajos y el 59% de los países de ingresos medios de la muestra tenían muchos menos profesionales sanitarios de los que necesitarían para proporcionar un conjunto básico de intervenciones sanitarias en materia de salud mental. Los 58 PIMB muestreados deberían aumentar su personal sanitario total del área de psiquiatría a 239 000 profesionales sanitarios a tiempo completo (o equivalente) para hacer frente a la escasez actual.

Conclusión

Para poder superar la gran escasez de trabajadores y servicios sanitarios en el área de salud mental en todos los PIMB, se necesitan políticas específicas para cada país.

РЕЗЮМЕ

Цель

Оценить дефицит специалистов в области охраны психического здоровья в странах с низким и средним доходом (СНСД).

Методы

Чтобы оценить, сколько психиатров, медицинских сестер и поставщиков психосоциальной помощи необходимо для предоставления медицинской помощи в области охраны психического здоровья всему населению обследуемых стран, мы использовали данные, полученные при применении разработанного ВОЗ Инструмента оценки систем психического здоровья (ИОСП-ВОЗ) в 58 СНСД, страновую информацию о бремени различных психических расстройств и гипотетический пакет услуг. Мы фокусировались на следующих восьми проблемах, которые ВОЗ считает приоритетными: депрессия, шизофрения, психозы, не относящиеся к шизофрении, суицид, эпилепсия, деменция, расстройства, связанные с употреблением алкоголя и нелегальных наркотиков и психические расстройства детей.

Результаты

Было обнаружено, что во всех странах с низким доходом и в 59% стран со средним доходом, входящих в нашу выборку, специалистов значительно меньше, чем требуется, чтобы предоставлять ключевой пакет мер вмешательства в области психического здоровья. В 58 СНСД, включенных в выборку, необходимо увеличить общую численность медицинских кадров в области охраны психического здоровья, на 239 000 специалистов в эквиваленте полной занятости, чтобы устранить наблюдающийся в настоящее время дефицит.

Вывод

Для преодоления значительного дефицита медицинских кадров и услуг в области охраны психического здоровья необходимы политические меры, разработанные с учетом условий конкретной страны.

摘要

目的

本文旨在估计中低收入国家(LMICs)精神卫生专业人员的短缺程度。

方法

我们使用的数据来自应用世界卫生组织精神卫生系统评估工具所获得的58个中低收入国家的数据,以及各国关于各种精神疾病负担的信息和一个假设的核心服务提供包用于评估相对于所研究国家的总人口而言应该有多少精神病医生、护士和心理保健人员才能满足精神卫生保健的需求。我们将关注点主要集中在世界卫生组织重视的以下八个问题:抑郁症、精神分裂症、精神分裂症之外的精神病、自杀、癫痫、痴呆、与酒精和非法药物使用相关的疾病和小儿精神失常。

结果

我们发现,在抽样样本中,所有低收入国家和59%的中等收入国家的现有精神卫生专业人员比应提供核心精神卫生干预所需要的精神卫生专业人员要少得多。所抽样的58个中低收入国家需增加239 000名全职精神卫生工作人员以解决目前的短缺问题。

结论

各中低收入国家需制定具体国家政策来解决精神卫生专业人员和相关服务的大量短缺问题。

Introduction

Mental, neurological, and substance abuse (MNS) disorders account for an increasing proportion of the global burden of disease. The World Health Organization (WHO) attributes to these disorders 14% of all of the world’s premature deaths and years lived with disability.1 In addition to imposing high costs on the health system, mental and neurological disorders and substance abuse also lead to lost worker productivity, impaired functioning, personal stigma, caregiver burden on family members, and, in some instances, to human rights violations.2–4

Although several cost-effective strategies reportedly reduce the disability associated with mental and neurological disorders and substance abuse,5–8 the fraction of those affected who receive appropriate treatment remains disturbingly low.9 This treatment gap appears especially wide in countries classified as low- or middle-income by The World Bank, where around 85% of the world’s population resides. In such countries, treatment rates for these disorders are suboptimal and range from 35% to 50%.9–11

Researchers, policy-makers and international agencies have issued calls for low- and middle- income countries (LMICs) to scale up the mental health components of their health systems.12–14 To accomplish this, they need to increase their workforces,14 particularly the number of trained professionals who can provide good mental health services. Although primary health-care professionals can provide the bulk of care, mental health professionals, namely psychiatrists, nurses and experts in psychosocial health, are needed to manage those patients who are referred for specialized care and to deliver training, support and supervision to non-specialists. Without these mental health professionals, LMICs will not have enough human resources to meet their populations’ mental health treatment requirements.15

The lack of reliable data on mental health systems in LMICs greatly hinders workforce planning efforts. Almost one-fourth of the world’s LMICs have no system for reporting basic mental health information.16 Even among LMICs that have such a system, many suffer from lack of accountability in reporting or from the inability to measure workforce capacity. Without information of this kind, countries cannot assess the scope and magnitude of the gap between the number of mental health workers needed and the number that is available.

We aim to provide health planners, policy researchers and government officials with country-specific estimates of the human resources that are required in the area of mental health to adequately care for the population in need of mental health care. We have focused on eight priority problems as defined by WHO: depression, schizophrenia, psychoses other than schizophrenia, suicide, epilepsy, dementia, disorders related to the use of alcohol and illicit drugs, and paediatric mental disorders (conduct or behavioural, intellectual and emotional disorders of childhood).13 For each of these disorders we used epidemiological information published by WHO as of July 2010,17in conjunction with the health services data available for 58 LMICs that had recently completed the WHO Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems (WHO-AIMS). For a detailed description of the validity and measurement properties of WHO-AIMS, please refer to Saxena et al.18

Methods

Current mental health workforce

To assess the size of the current workforce devoted to mental health care in the study countries, we retrieved data from WHO-AIMS, an assessment tool designed for LMICs that provides a comprehensive summary of each country’s mental health system. WHO-AIMS, described in detail by Saxena et al.,18 includes 155 indicators covering six domains: policy and legislative framework, mental health services, mental health in primary care, human resources, public education and monitoring and research. We retrieved workforce data from the human resources domain, where LMICs were asked to report the “number of staff working in or for mental health facilities or private practice”.19 Respondents provided a count of professionals of various types, whom we grouped into three broad professional categories: psychiatrists, nurses and psychosocial care providers. Nurses included general nursing staff providing mental health services and psychiatric nurses; psychosocial workers included psychologists, social workers and occupational therapists. Our rationale for grouping these categories together was that in LMICs these professionals often carry out the same range of tasks. They have all received formal training in psychology, social work or occupational therapy from a recognized university or technical school and are responsible for delivering psychosocial interventions within the mental health system.

We included in the analysis 58 WHO Member States and territories, as well as provinces and states within a country, that were invited to complete a WHO-AIMS assessment between February 2005 and June 2009. They were chosen based on their ability to collect the required information and their willingness to participate in the study, so in essence they represented a convenience sample. For brevity, we shall refer to all these entities as countries throughout the paper, but they are not all countries strictly speaking. We note, however, that two assessments that were performed at the regional level (i.e. Hunan, China, and Uttarakhand, India) were not extrapolated to the respective countries as a whole and therefore should not be considered nationally representative.

Needs-based mental health workforce targets

In its 2008 report, WHO’s Mental health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) specified eight problems that LMICs should prioritize, since they account for 75% of the global burden of mental and neurological conditions and substance abuse disorders. They are depression, schizophrenia, psychoses other than schizophrenia, suicide, epilepsy, dementia, the abuse of alcohol and use of illicit drugs, and paediatric mental disorders.13 To meet the priority definition, the condition must impose substantial disability, morbidity or mortality, lead to high economic expenditure or be associated with violations of human rights. The mhGAP report contains the best available scientific and epidemiological evidence surrounding mental, neurological and substance abuse disorders, and the ones prioritized by WHO have been common wherever prevalence has been measured. Moreover, the disorders that are prioritized are those that substantially undermine childrens’ learning skills and adults’ ability to function within the family and in broader society. Because these conditions are highly prevalent and cause impairment, they contribute substantially to the total burden of disease. We refer the reader to the mhGAP report for more information.13

We used population-based estimates of the prevalence of these disorders to make needs-based estimates of workforce requirements. We then applied to this target population the recommended health-care service delivery models and multiplied appropriate staffing ratios (both adapted from Chisholm et al.)6 to the expected volume of inpatient and outpatient services to yield target counts of psychiatrists, nurses and psychosocial care providers. Our focus on these workers led us to exclude all health professionals outside the sphere of mental health (e.g. paediatricians and educational system support staff) and of workers in “mixed practice”. In addition, we did not include neurologists in the workforce analysis, as primary care professionals in LMICs where resources are scarce are increasingly expected to diagnose and treat epilepsy.20

Prevalence of priority disorders

Since most LMICs do not routinely conduct their own population-based surveys, we used sub-regional prevalence estimates generated as part of the 2004 WHO Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Project, whose figures come from comprehensive reviews and syntheses of the available epidemiological evidence.17 For the two priority disorders not included in the 2004 GBD Project (e.g. illicit substance abuse and paediatric mental disorders) we obtained population-based prevalence rates from the peer-reviewed epidemiologic literature.21–23 To calculate the approximate prevalence of suicidal ideation, we multiplied the GBD rate of deaths from suicide by a factor of 20, which is the estimated number of suicidal ideations per suicide.24,25

Table 1 shows the mean prevalence of each of the eight priority mhGAP conditions in the six WHO regions. We classified illicit substance abuse disorders and paediatric mental disorders into sub-categories having distinct requirements in terms of care and human resource levels. We multiplied the estimated prevalence in all the age groups affected by each disorder to estimate the actual numbers implicated in each country. This calculation yielded the total number of cases meeting the definition given in the ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders (Table 1).25–32

Table 1. Prevalence (%) of the mental, neurological and substance abuse problems prioritized in the mental health Gap Action Programme of the World Health Organization (WHO), by WHO region.

| WHO region | Prevalence by disorder |

Population (millions) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophreniaa | Bipolara | Depressionb | Suicidec | Epilepsyd | Dementiae | Substance abuse |

Paediatric |

|||||||

| Alcohol (hazardous)f | Opioidsg | Other drugsh | Intellectuali | Conduct/ behaviouralj | Emotionalk | |||||||||

| African | 0.28 | 0.37 | 2.18 | 0.14 | 1.04 | 0.09 | 0.52 | 0.05 | 0.29 | 1.50 | 4.25 | 4.25 | 316.5 | |

| Americas | 0.42 | 0.45 | 2.80 | 0.16 | 1.26 | 0.34 | 2.68 | 0.04 | 0.37 | 1.50 | 4.25 | 4.25 | 138.9 | |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 0.36 | 0.41 | 2.79 | 0.15 | 0.55 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.44 | 0.14 | 1.50 | 4.25 | 4.25 | 460.3 | |

| European | 0.50 | 0.50 | 2.83 | 0.30 | 0.42 | 0.51 | 4.01 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 1.50 | 4.25 | 4.25 | 110.2 | |

| South-East Asia | 0.37 | 0.43 | 2.88 | 0.26 | 0.58 | 0.17 | 1.28 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 1.50 | 4.25 | 4.25 | 276.8 | |

| Western Pacific | 0.44 | 0.50 | 2.84 | 0.13 | 0.39 | 0.33 | 2.77 | 0.02 | 0.19 | 1.50 | 4.25 | 4.25 | 178.4 | |

a Cases that meet ICD-10 criteria only.

b Unipolar depressive disorder, major depressive episode meeting ICD-10 criteria.

c Global Burden of Disease self-inflicted injury death rate multiplied by a factor of twenty.24,25

d Cases meeting International League Against Epilepsy definition (excluding epilepsy secondary to other diseases or injury).

e Moderate and severe dementia: Global Burden of Disease Estimate of Alzheimer and dementia multiplied by a correction factor of 0.5 and weighted for age.26

f Cases meeting ICD-10 criteria for alcohol dependence and harmful use (F10.1 and F 10.2), excluding cases with comorbid depressive episode.

g Cases meeting ICD-10 criteria for opioid dependence and harmful use (F 11.1 and F 11. 2) excluding cases with comorbid depressive episode.

h Cases meeting ICD-10 criteria for cocaine dependence and harmful use (F 14.1 and F 14.2) or amphetamine use.

i Moderate and severe forms of mental retardation, based on international estimates of prevalence.27–29

j Prevalence of severe aggression, disobedience, and irritability based WHO expert panel estimates.

k WHO-based estimate of children that meet criteria for major depression or anxiety related disorders.30,31

Treatment coverage targets

Target treatment coverage rates for each disorder were determined on the basis of three factors: the severity of the disorder, the ability to detect cases in the population and the probability that identified cases will seek care. Based on these considerations and consistent with estimates from the literature,6 we established the following conservative target coverage rates: 80% for schizophrenia, suicidal ideation, epilepsy, and dementia; 50% for use of opioids and other illicit drugs; 33% for depression; 25% for alcohol abuse; and 20% for paediatric mental disorders. We assigned a high treatment coverage target to schizophrenia because of the large disability burden attached to it and the intensity of the symptoms. In contrast, we set a treatment coverage target of 20% for paediatric mental disorders since it is the coverage level normally attained in the wealthiest high-income countries.23,33,34

Service delivery models

The next step was to apply intervention and service delivery models to each of the eight priority disorders.6 The models were based on the results of WHO sub-regional cost-effectiveness studies35–38 and of international needs assessment research in developing countries.6,39,40 The assumption underlying the models was that most cases receive treatment at the primary care level and that patients with more severe or complex disorders are referred to specialists.41–44 The frequency with which people affected by the mental, neurological and substance abuse disorders included in this study require inpatient and outpatient services varies considerably. Table 2 displays the target service delivery models for each disorder. The treatment models were constructed on the basis of (i) the percentage of cases needing care in each service setting; (ii) the average annual number of health-care visits per person and (iii) whether or not the inpatient or outpatient visits required a bed. Screening and diagnostic services, which all three types of professionals included in this study are increasingly expected to perform in LMICs, were included under the “outpatient and day care” setting. We calculated health service needs separately for each disorder and added the values to obtain an aggregate estimate.

Table 2. Target mental health service delivery models in low- and middle-income countries for the mental, neurological and substance abuse disorders prioritized by the World Health Organization.

| Service type | Disorder |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophreniaa |

Bipolara |

Depressiona |

Suicideb |

Epilepsy |

Dementia |

Substance abusec |

Paediatricd |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alcohol (hazardous) |

Opioids |

Other drugse |

Conductf/ behaviouralg |

Intellectual |

Emotional |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| SCh | MURi | SCh | MURi | SCh | MURi | SCh | MURi | SCh | MURi | SCh | MURi | SCh | MURi | SCh | MURi | SCh | MURi | SCh | MURi | SCh | MURi | SCh | MURi | ||||||||||||

| Inpatient and residential bed–days | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mental hospital (long stay) | 2.0 | 90 | 2 | 90 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Community residential (long-stay) | 2.5 | 180 | 2.5 | 180 | 0.5 | 90 | 1 | 90 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 270 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 60 | 10 | 60 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 90 | |||||||||||

| Community psychiatric (acute care) | 15.0 | 28 | 15 | 28 | 2 | 14 | 2 | 14 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2.7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 14 | |||||||||||

| General hospital inpatient unit | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0 | 0 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||||||

| Outpatient and day care visits | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Day care | 7.5 | 100 | 7.5 | 100 | 1 | 50 | 1 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 26 | 10 | 12 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 50 | |||||||||||

| Hospital outpatient | 50 | 12 | 50 | 12 | 20 | 7 | 20 | 7 | 50 | 4 | 25 | 6 | 10 | 2 | 25 | 11 | 10 | 12 | 25 | 3 | 20 | 4 | 20 | 7 | |||||||||||

| Primary health care (treatment) | 30 | 6 | 30 | 6 | 30 | 7 | 30 | 7 | 100 | 4 | 50 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 75 | 24 | 10 | 6 | 100 | 6.2 | 22 | 4 | 30 | 7 | |||||||||||

| Primary health care (screening) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 4 | 7 | 1 | |||||||||||

| Psychosocial treatment5 | 30 | 8 | 30 | 8 | 20 | 6 | 20 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 6 | |||||||||||

MUR, mean utilization rate; SC, service coverage.

a Model taken from Chisholm et al.6

b For suicide (high risk prevention) the depression treatment model was used, with pharmacological treatment excluded.

c Separate models were developed for opioid use and other drug use disorders.

d Three childhood mental disorder models were developed based on symptom intensity (mild, moderate and severe), service type (initial assessment or follow-up care) and outpatient setting (hospital outpatient or primary-health-care setting). A weighted average of use per case was derived from the intellectual disabilities models.

e Cocaine, amphetamines.

f Conduct disorders include oppositional defiant disorder. Estimates for conduct disorders were based on South Africa’s child and adolescent mental health service sector.41,42

g Behavioural disorders include hyperkinetic disorder and antisocial behaviour.

h Percentage of people with a given disorder who are expected to use the service or resource (bed–days or visits) over the course of one year.2

I Mean annual number of bed–days or visits among people being treated for a given disorder who are expected to use the service or resource.3 Index therapies used.

Mental health workforce staffing

For both the outpatient and inpatient settings we derived the total number of full-time-equivalent (FTE) staff required, with FTE defined as the number of working hours corresponding to one full-time employee during a fixed year. To assist LMICs in allocating human resources for mental health, we calculated workforce requirements for outpatient services by applying workforce capacity estimates developed by WHO. We assumed that staff work 225 days per year and provide, on average, 11 consultations per day. For each disorder considered in this study, we divided the total number of expected outpatient visits by 2475 (225 × 11) to obtain the total number of full-time-equivalent staff needed for outpatient care. After classifying mental health professionals into psychiatrists, nurses and psychosocial care providers, we applied staffing ratios to the estimates of full-time-equivalent staff to obtain target numbers of each of these professionals.6 The staffing ratios used, fully presented in a table in Chisholm et al.,6 were specific for each disorder, treatment setting (e.g. hospital outpatient) and World Bank country income classification.

To estimate the full-time-equivalent staff required to meet inpatient service targets, we used estimated bed–days as the starting input. We assumed that hospitals operate at 85% capacity and applied this correction factor to obtain the targeted number of inpatient beds. To calculate the number of full-time-equivalent inpatient staff needed to manage the population affected by each disorder, we multiplied staff:bed ratios for LMICs extracted from the literature6,41,42 by the targeted number of inpatient beds.

Workforce shortage or surplus

We summed the needs-based inpatient and outpatient full-time-equivalent staff to arrive at a single targeted total, which we then subtracted from the current staffing levels given in WHO-AIMS. The difference reflects the magnitude of the global mental health workforce shortage (if a negative value) or surplus (if a positive value).

Results

Current and target staffing levels for mental health professionals vary widely both across and within WHO regions (Table 3). LMICs in the African Region and the South-East Asia Region report fewer psychiatrists than the Region of the Americas or the European Region. Large within-region variations are highlighted by the 20-fold difference in the number of psychiatrists per 100 000 population between the Sudan and the Islamic Republic of Iran, two middle-income countries in the Region of the Eastern Mediterranean (0.06 in the Sudan versus 1.19 in the Islamic Republic of Iran). For all three categories of mental health professionals, middle-income countries routinely report a larger number of staff per population than do low-income countries.

Table 3. Mental health workforce shortages in 58 low- and middle-income countries.

| WHO region & country/territorya | WB income category | Mental health professionals (no. per 100 000 population) |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychiatrists |

Nurses |

Psychosocial care providers |

|||||||||||||

| Currentb | Target | Differencec | Suggested increase | Currentb | Target | Differencec | Suggested increase | Currentb | Target | Differencec | Suggested increase | ||||

| Africa | |||||||||||||||

| Benin | LIC | 0.19 | 1.03 | −0.84 | 66 | 0.21 | 9.49 | −9.28 | 730 | 0.29 | 8.63 | −8.33 | 656 | ||

| Burundi | LIC | 0.01 | 0.92 | −0.91 | 67 | 0.42 | 8.65 | −8.23 | 607 | 1.13 | 8.08 | −6.95 | 513 | ||

| Congo | MIC | 0.11 | 0.89 | −0.79 | 27 | 0.70 | 8.99 | −8.29 | 283 | 1.05 | 6.92 | −5.87 | 200 | ||

| Eritrea | LIC | 0.06 | 0.89 | −0.84 | 37 | 0.33 | 8.37 | −8.04 | 360 | 0.44 | 7.88 | −7.44 | 333 | ||

| Ethiopia | LIC | 0.02 | 0.89 | −0.87 | 659 | 0.26 | 8.34 | −8.08 | 6113 | 0.88 | 7.85 | −6.97 | 5 275 | ||

| Nigeria | LIC | 0.15 | 1.03 | −0.88 | 1240 | 2.41 | 9.56 | −7.15 | 10 078 | 0.93 | 8.69 | −7.75 | 10 923 | ||

| Uganda | LIC | 0.08 | 0.81 | −0.73 | 211 | 0.79 | 7.66 | −6.88 | 1974 | 0.27 | 7.46 | −7.19 | 2 063 | ||

| South Africa | MIC | 0.28 | 1.03 | −0.75 | 361 | 10.08 | 10.36 | −0.28 | 135 | 1.58 | 7.69 | −6.11 | 2 937 | ||

| Americas | |||||||||||||||

| Argentina | MIC | 9.20 | 1.96 | 7.24 | 0d | 12.91 | 19.83 | −6.92 | 2682 | 13.19 | 12.62 | 0.57 | 0d | ||

| Belize | MIC | 0.66 | 1.32 | −0.66 | 2 | 7.97 | 13.38 | −5.41 | 15 | 9.29 | 9.58 | −0.29 | 1 | ||

| Bolivia | MIC | 1.06 | 1.37 | −0.31 | 29 | 0.35 | 13.86 | −13.51 | 1241 | 2.57 | 9.78 | −7.21 | 662 | ||

| Chile | MIC | 4.65 | 1.84 | 2.81 | 0d | 1.65 | 18.66 | −17.00 | 2771 | 14.25 | 12.16 | 2.09 | 0d | ||

| Costa Rica | MIC | 3.06 | 1.61 | 1.45 | 0d | 4.13 | 16.33 | −12.20 | 528 | 12.22 | 11.05 | 1.17 | 0d | ||

| Dominican Republic | MIC | 2.08 | 1.50 | 0.58 | 0d | 1.61 | 15.20 | −13.59 | 1296 | 8.01 | 10.44 | −2.42 | 231 | ||

| Ecuador | MIC | 2.51 | 1.57 | 0.94 | 0d | 0.93 | 15.90 | −14.97 | 1956 | 5.84 | 10.85 | −5.01 | 655 | ||

| El Salvador | MIC | 1.39 | 1.53 | −0.14 | 8 | 2.12 | 15.45 | −13.33 | 808 | 6.51 | 10.52 | −4.01 | 243 | ||

| Guatemala | MIC | 0.57 | 1.27 | −0.70 | 89 | 1.28 | 12.83 | −11.55 | 1469 | 0.57 | 9.24 | −8.67 | 1 102 | ||

| Guyana | MIC | 0.53 | 1.62 | −1.09 | 8 | 0.40 | 16.34 | −15.94 | 121 | 8.66 | 11.29 | −2.63 | 20 | ||

| Honduras | MIC | 0.82 | 1.30 | −0.48 | 33 | 2.58 | 13.12 | −10.54 | 726 | 2.70 | 9.40 | −6.70 | 461 | ||

| Jamaica | MIC | 1.13 | 1.66 | −0.53 | 14 | 9.55 | 16.77 | −7.22 | 192 | 16.09 | 11.13 | 4.96 | 0d | ||

| Nicaragua | MIC | 0.91 | 1.16 | −0.25 | 14 | 1.71 | 11.72 | −10.01 | 546 | 5.37 | 8.64 | −3.27 | 179 | ||

| Panama | MIC | 3.47 | 1.60 | 1.87 | 0d | 4.38 | 16.16 | −11.78 | 380 | 8.83 | 11.03 | −2.20 | 71 | ||

| Paraguay | MIC | 1.31 | 1.41 | −0.10 | 6 | 1.58 | 14.22 | −12.65 | 747 | 3.96 | 9.97 | −6.01 | 355 | ||

| Suriname | MIC | 1.45 | 1.61 | −0.16 | 1 | 13.96 | 16.31 | −2.35 | 12 | 34.38 | 11.13 | 23.25 | 0d | ||

| Uruguay | MIC | 19.36 | 2.26 | 17.10 | 0d | 0.69 | 22.90 | −22.20 | 739 | 10.57 | 14.08 | −3.52 | 117 | ||

| Eastern Mediterranean | |||||||||||||||

| Afghanistan | LIC | 0.01 | 0.97 | −0.97 | 237 | 0.15 | 9.20 | −9.05 | 2218 | 0.41 | 8.71 | −8.30 | 2 035 | ||

| Djibouti | MIC | 0.33 | 1.05 | −0.72 | 6 | 0.83 | 10.62 | −9.79 | 79 | 0.33 | 8.08 | −7.75 | 62 | ||

| Egypt | MIC | 1.44 | 1.16 | 0.28 | 0d | 2.60 | 11.79 | −9.19 | 7089 | 1.03 | 8.64 | −7.60 | 5 867 | ||

| Iraq | MIC | 0.34 | 1.04 | −0.70 | 199 | 0.54 | 10.53 | −9.99 | 2822 | 0.65 | 8.08 | −7.43 | 2 099 | ||

| Islamic Republic of Iran | MIC | 1.19 | 1.28 | −0.09 | 65 | 7.82 | 12.96 | −5.13 | 3633 | 52.17 | 9.52 | 42.66 | 0d | ||

| Jordan | MIC | 1.14 | 1.06 | 0.08 | 0d | 3.95 | 10.70 | −6.75 | 376 | 1.94 | 8.27 | −6.33 | 352 | ||

| Morocco | MIC | 1.02 | 1.62 | −0.59 | 181 | 2.17 | 16.46 | −14.30 | 4359 | 1.71 | 10.27 | −8.56 | 2 610 | ||

| Pakistan | LIC | 0.13 | 1.18 | −1.05 | 1735 | 18.86 | 10.98 | 7.88 | 0d | 2.30 | 9.84 | −7.54 | 12 508 | ||

| Somalia | LIC | 0.07 | 1.07 | −1.00 | 83 | 0.33 | 10.04 | −9.71 | 811 | 1.20 | 9.39 | −8.19 | 684 | ||

| Sudan | MIC | 0.06 | 1.04 | −0.98 | 380 | 0.01 | 10.53 | −10.52 | 4070 | 0.75 | 8.03 | −7.28 | 2 818 | ||

| Tunisia | MIC | 1.53 | 1.35 | 0.18 | 0d | 3.71 | 13.68 | −9.97 | 984 | 2.97 | 9.80 | −6.84 | 675 | ||

| European | |||||||||||||||

| Albania | MIC | 3.20 | 1.79 | 1.40 | 0d | 7.00 | 18.29 | −11.28 | 351 | 3.93 | 11.42 | −7.49 | 233 | ||

| Armenia | MIC | 5.88 | 2.10 | 3.78 | 0d | 5.42 | 21.42 | −16.00 | 490 | 22.91 | 12.79 | 10.12 | 0d | ||

| Azerbaijan | MIC | 5.18 | 1.64 | 3.54 | 0d | 8.36 | 16.78 | −8.42 | 711 | 8.63 | 10.70 | −2.07 | 175 | ||

| Georgia | MIC | 5.90 | 2.35 | 3.55 | 0d | 7.71 | 23.98 | −16.28 | 727 | 22.88 | 13.92 | 8.97 | 0d | ||

| Kyrgyzstan | MIC | 3.41 | 1.53 | 1.88 | 0d | 9.24 | 15.56 | −6.32 | 330 | 13.57 | 10.22 | 3.35 | 0d | ||

| Latvia | MIC | 8.31 | 2.69 | 5.62 | 0d | 35.72 | 27.41 | 8.31 | 0d | 28.52 | 15.97 | 12.55 | 0d | ||

| Republic of Moldova | MIC | 4.78 | 1.72 | 3.06 | 0d | 15.35 | 17.63 | −2.27 | 85 | 29.51 | 10.86 | 18.65 | 0d | ||

| Tajikistan | LIC | 1.12 | 1.38 | −0.26 | 17 | 1.93 | 12.79 | −10.86 | 710 | 6.33 | 10.45 | −4.12 | 269 | ||

| Ukraine | MIC | 8.66 | 2.65 | 6.01 | 0d | 26.20 | 27.03 | −0.82 | 385 | 42.47 | 15.81 | 26.66 | 0d | ||

| Uzbekistan | LIC | 3.56 | 1.59 | 1.97 | 0d | 6.54 | 14.61 | −8.06 | 2122 | 6.37 | 11.54 | −5.17 | 1 362 | ||

| South-East Asia | |||||||||||||||

| Bangladesh | LIC | 0.07 | 1.27 | −1.20 | 1831 | 0.20 | 11.79 | −11.59 | 17 753 | 0.22 | 10.06 | −9.84 | 15 066 | ||

| Bhutan | MIC | 0.45 | 1.19 | −0.75 | 5 | 1.49 | 12.11 | −10.63 | 69 | 2.86 | 8.62 | −5.77 | 37 | ||

| India (Uttarakhand province)e | MIC | 0.08 | 1.20 | −1.12 | 101 | 4.78 | 12.16 | −7.38 | 669 | 2.87 | 8.65 | −5.78 | 525 | ||

| Maldives | MIC | 0.69 | 1.17 | −0.48 | 1 | 1.38 | 11.85 | −10.46 | 31 | 2.42 | 8.53 | −6.11 | 18 | ||

| Nepal | LIC | 0.13 | 1.19 | −1.06 | 288 | 0.27 | 11.03 | −10.76 | 2928 | 0.19 | 9.56 | −9.36 | 2 549 | ||

| Sri Lanka | MIC | 0.18 | 1.47 | −1.29 | 251 | 1.91 | 14.92 | −13.01 | 2542 | 3.55 | 9.96 | −6.41 | 1 252 | ||

| Thailand | MIC | 0.66 | 1.46 | −0.79 | 524 | 3.81 | 14.85 | −11.04 | 7278 | 2.81 | 9.73 | −6.91 | 4 559 | ||

| Timor Leste | MIC | 0.11 | 0.95 | −0.84 | 8 | 15.32 | 9.56 | 5.76 | 0d | 6.80 | 7.29 | −0.50 | 5 | ||

| Western Pacific | |||||||||||||||

| China (Hunan province) | MIC | 1.41 | 2.41 | −1.00 | 63 | 3.19 | 24.56 | −21.37 | 1352 | 4.13 | 14.16 | −10.03 | 634 | ||

| Mongolia | MIC | 0.51 | 1.84 | −1.33 | 34 | 7.62 | 18.77 | −11.15 | 284 | 8.49 | 11.96 | −3.47 | 89 | ||

| Philippines | MIC | 0.42 | 1.49 | −1.07 | 916 | 0.91 | 15.08 | −14.17 | 12 116 | 2.11 | 10.40 | −8.29 | 7 090 | ||

| Viet Nam | LIC | 0.35 | 2.05 | −1.70 | 1426 | 2.10 | 18.39 | −16.29 | 13 692 | 1.93 | 13.45 | −11.52 | 9 687 | ||

| Total shortage (no.) | LMIC | 11 222 | 127 575 | 100 256 | |||||||||||

LIC, low-income country; LMIC, low- and middle-income countries; MIC, middle-income country; WB, World Bank; WHO, World Health Organization.

a The following had missing values for at least one of the professional groups classified under psychosocial care providers: Armenia, Benin, Bhutan, China (Hunan province), Egypt, Georgia, India (Uttarakhand province), Jordan, Nepal, Nigeria, Paraguay, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Uruguay and Uzbekistan.

b The current supply of full-time-equivalent staff was obtained from the World Health Organization Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems (WHO-AIMS version V.2.2).19

c To calculate workforce shortages, full-time-equivalent staff target levels were subtracted from current supply levels. It was assumed that a surplus in one country did not offset shortages in other countries.

d In adding the workforce shortages for each specialty, all surplus values were converted to 0.

e Uttarakhand (India) had a missing value for nurses; the mean value for its WHO region (South-East Asia) and income level (MIC) was used instead.

Across the 58 LMICs in this study, the estimated number of mental health professionals required is 362 000 (20 000 psychiatrists, 195 000 nurses and 147 000 psychosocial care providers). This represents an average of 22.3 mental health professionals per 100 000 population in low-income countries and of 26.7 professionals per 100 000 population in middle-income countries.

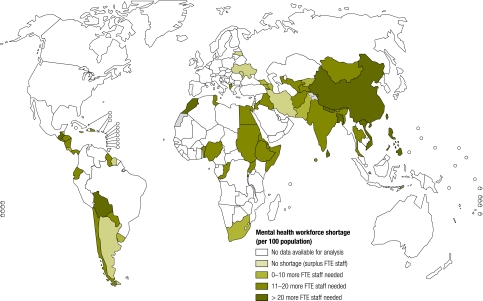

The column labelled “difference” in Table 3 shows the mental health workforce shortage (−) or surplus (+) for each country. Of the 58 study countries, 67% showed a shortage of psychiatrists, 95% a shortage of nurses and 79% a shortage of psychosocial care providers. In absolute figures, these workforce deficits amounted to a total shortage of approximately 11 000 psychiatrists, 128 000 nurses and 100 000 psychosocial care providers. Thus, an additional 239 000 full-time-equivalent staff would be needed globally to treat the current burden of the eight mental, neurological and substance abuse problems that WHO has prioritized. Fig. 1 maps the shortage (or surplus) for all LMICs in the analysis. Of the 58 countries included, 51 show a shortage and 9 require at least 20 additional mental health professionals per 100 000 population to meet the needs-based target levels of care.

Fig. 1.

Mental health workforce shortages in 58 low- and middle-income countriesa

FTE, full-time-equivalent.

a Data for India and China are from only one province (Uttarakhand province and Hunan province, respectively).

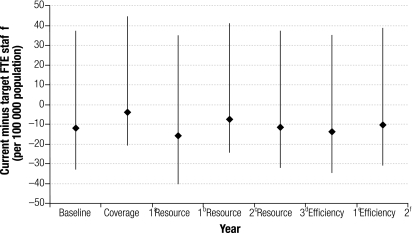

We conducted a series of sensitivity analyses to determine how the shortage/surplus for each of the 58 LMICs responded to changes in three key inputs: target treatment coverage level, rates of inpatient and outpatient service utilization and daily case workload (Fig. 2). A reduction in target treatment coverage rates affected workforce estimates more than changes in service utilization rates or in workload capacity. When target treatment coverage for all disorders was substantially reduced, the mean workforce gap dropped from 11 to 4 additional mental health professionals per 100 000 population. In contrast, changes in workforce efficiency (raising or lowering outpatient consultation capacity by 20%) did not substantially alter the shortage estimates from baseline levels (see efficiency scenarios 1 and 2). Of the countries classified as low-income, only one showed a workforce surplus in at least one of the six scenarios; 43 of the 58 LMICs (74%) showed a workforce shortage in all scenarios.

Fig. 2.

Impact of changes in target coverage, resource utilization and case workload on mental health workforce shortage estimates in 58 low- and middle-income countries

FTE, full-time equivalent; LMICs, low-and-middle-income countries.

The vertical lines represent the range of values for the shortages found in the 58 LMICs analysed; the diamonds represent the average shortage. A negative value indicates a shortage.

a Coverage 1: reduce treatment coverage rates for all disorders: schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, suicidal ideation and epilepsy (from 80% to 50%); dementia, use of opioids and use of other illicit drugs (from 50% to 40%); depression (from 33% to 25%); alcohol abuse (from 25% to 20%); paediatric disorders (from 20% to 10%).

b Resource 1: increase the length of inpatient stay (acute and residential care) by 25%.

c Resource 2: decrease the length of inpatient stay (acute and residential care) by 25%.

d Resource 3: reduce the target coverage rate for outpatient services by 10%; increase the target coverage rate for primary-health-care services by 10%.

e Efficiency 1: reduce daily outpatient consultation capacity by 20%.

f Efficiency 2: increase daily outpatient consultation capacity by 20%.

Discussion

We have capitalized on current workforce estimates to provide the first in-depth evaluation of mental health staffing shortages in LMICs. Our needs-based analysis of 58 such countries has revealed substantial deficits in the mental health workforce. All of the low-income countries and 59% of the middle-income countries included in this study experience a needs-based shortage, which points to an inability to provide appropriate care to their populations afflicted with mental, neurological and substance abuse disorders. Overall, LMICs would need to increase their workforces by an estimated 239 000 full-time-equivalent staff (psychiatrists, nurses and psychosocial care providers) to satisfactorily address the current burden of priority disorders.

For over 30 years, international organizations have been recommending that countries increase their mental health workforce, and WHO's call for a scale-up in the mhGAP report makes the task all the more urgent.13,14,45 Unfortunately, progress in achieving parity in the workforce for the care of physical and mental ailments has been slow, perhaps owing to the absence of clear, quantitative benchmarks to guide the prudent allocation of human resources in mental health.18,46 Our report attempts to fill this void. We provide government officials and health-care planners with quantitative estimates that will help them to “scale up” the human resources required to meet the mental health care needs of their populations.

The reader should view our estimates in the light of several limitations. First, although we used the best available epidemiologic data to define needs-based treatment levels, many LMICs do not report population-based prevalence, particularly for paediatric disorders. For this reason we applied to these disorders conservative prevalence and treatment coverage levels. Second, our target service delivery models rest on the assumption that implementation, operational structure and efficiency are identical across LMICs. These limitations imply that the estimates we provide represent approximate, rather than definitive, benchmarks for human resources. The reader, moreover, should view the sensitivity analyses we performed as indicative of the variability of our estimates.

We focused on the eight disorders prioritized by WHO’s mhGAP to the exclusion of other conditions (e.g. personality disorders) that comprise about 25% of the burden of all mental, neurological and substance abuse disorders in LMICs.17 In addition, our target treatment coverage levels for these priority disorders may be viewed as suboptimal by some policy-makers. It is therefore conceivable that results underestimate mental health workforce shortages.

To assess workforce shortages we had to make several assumptions. For example, we assumed that within a given country, staff surpluses in one specialty area did not offset shortages in another. This in turn rests on the assumption that different specialties have different training requirements that preclude the transferability of staff across professional boundaries. However, some governments may choose to employ specific management mechanisms and incentives to facilitate task-shifting across professions, while others may incentivize team work at the community level as part of the strategy to scale up primary health care.47,48 Given the challenges involved, we encourage government officials to work with WHO and other partners in tailoring our general workforce model to the mental health systems of their particular countries. Other circumstances unique to each country, such as the high prevalence of a condition not specified among the eight mhGAP priority disorders, can also compel governments to seek technical cooperation. Countries interested in carrying out their own mental health workforce needs assessment should refer to the step-by-step WHO guide Planning and budgeting to deliver services for mental health.49

Conclusion

Our findings should encourage subsequent analyses to determine not only the human resource levels required for mental health but also the proper workforce skill mix.50 Various strategies may optimize efficiency of the existing workforce: shared competencies, substitution between health professions, and multiple tasks performed by a particular category of providers. In addition, task-shifting, which rationally redistributes tasks among teams, may usefully compensate for shortages of specialist mental health professionals.51 The success of these strategies depends on strong, well coordinated management mechanisms and incentives. We encourage future evaluation of these approaches.

The workforce represents one key component of the mental health system. However, to address the three main shortcomings of mental health care in most LMICs – scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency – governments will need a comprehensive approach.15,16,52 The success of such a strategy will require, at the very minimum, allocation of health budgets towards MNS disorders, investment to recruit and train a mental health workforce, and a concerted effort to destigmatize MNS disorders.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349:1436–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07495-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu TW. The economic burden of depression and reimbursement policy in the Asia Pacific region. Australas Psychiatry. 2004;12(Suppl):S11–5. doi: 10.1080/j.1039-8562.2004.02100.x-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kadri N, Manoudi F, Berrada S, Moussaoui D. Stigma impact on Moroccan families of patients with schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49:625–9. doi: 10.1177/070674370404900909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsang HWH, Tam PKC, Chan F, Cheung WM. Sources of burdens on families of individuals with mental illness. Int J Rehabil Res. 2003;26:123–30. doi: 10.1097/00004356-200306000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chatterjee S, Patel V, Chatterjee A, Weiss HA. Evaluation of a community-based rehabilitation model for chronic schizophrenia in rural India. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:57–62. doi: 10.1192/bjp.182.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chisholm D, Lund C, Saxena S. Cost of scaling up mental healthcare in low- and middle-income countries. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:528–35. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.038463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Disease control priorities related to mental, neurological, developmental and substance abuse disorders Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel V, Araya R, Chatterjee S, Chisholm D, Cohen A, De Silva M, et al. Treatment and prevention of mental disorders in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2007;370:991–1005. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang PS, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Borges G, Bromet EJ, et al. Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO world mental health surveys. Lancet. 2007;370:841–50. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61414-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kohn R, Saxena S, Levav I, Saraceno B. The treatment gap in mental health care. Bull World Health Organ. 2004;82:858–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine JP, et al. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA. 2004;291:2581–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chisholm D, Flisher AJ, Lund C, Patel V, Saxena S, Thornicroft G, et al. Scale up services for mental disorders: a call for action. Lancet. 2007;370:1241–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.mhGAP: mental Health Action Programme: scaling up care for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [PubMed]

- 14.The world health report 2001: mental health: new understanding, new hope Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saraceno B, van Ommeren M, Batniji R, Cohen A, Gureje O, Mahoney J, et al. Barriers to improvement of mental health services in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2007;370:1164–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61263-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mental health atlas, 2005. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.The global burden of disease: 2004 update Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saxena S, Lora A, van Ommeren M, Barrett T, Morris J, Saraceno B. WHO’s Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems: collecting essential information for policy and service delivery. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58:816–21. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.58.6.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.WHO-AIMS 2.2: World Health Organization Assessment Instrument for Mental Health Systems. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.mhGAP intervention guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [PubMed]

- 21.Degenhardt L, Hall H, Warner-Smith M, Lynskey M. Illicit drug use. In: Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A, Murray CJL, editors. Comparative quantification of health risks. Global and regional burden of diseases attributable to selected major risk factors Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patel V, Flisher AJ, Hetrick S, McGorry P. Mental health of young people: a global public-health challenge. Lancet. 2007;369:1302–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60368-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belfer ML. Child and adolescent mental disorders: the magnitude of the problem across the globe. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49:226–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmidtke A, Bille-Brahe U, DeLeo D, Kerkhof A, Bjerke T, Crepet P, et al. Attempted suicide in Europe: rates, trends and sociodemographic characteristics of suicide attempters during the period 1989–1992. Results of the WHO/EURO Multicentre Study on Parasuicide. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;93:327–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb10656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kerkhof A. Attempted suicide: patterns and trends. In: Hawton K, van Heeringen K, editors. The international handbook of suicide and attempted suicide. London: Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodriguez JJ, Ferri CP, Acosta D, Guerra M, Huang Y, Jacob KS, et al. Prevalence of dementia in Latin America, India, and China: a population-based cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2008;372:464–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61002-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Durkin MS, Hasan ZM, Hasan KZ. Prevalence and correlates of mental retardation among children in Karachi, Pakistan. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:281–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tekle-Haimanot R, Abebe M, Gebre-Mariam A, Forsgren L, Heijbel J, Holmgren G, et al. Community-based study of neurological disorders in rural central Ethiopia. Neuroepidemiology. 1990;9:263–77. doi: 10.1159/000110783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xie ZH, Bo SY, Zhang XT, Liu M, Zhang ZX, Yang XL, et al. Sampling survey on intellectual disability in 0–6-year-old children in China. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2008;52:1029–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2008.01048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gureje O, Omigbodun OO, Gater R, Acha RA, Ikuesan BA, Morris J. Psychiatric disorders in a paediatric primary care clinic. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;165:527–30. doi: 10.1192/bjp.165.4.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adewuya AO, Ola BA, Aloba OO. Prevalence of major depressive disorders and a validation of the Beck Depression Inventory among Nigerian adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;16:287–92. doi: 10.1007/s00787-006-0557-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB. Unmet need for mental health care among U.S. children: variation by ethnicity and insurance status. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1548–55. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Focusing on children’s mental health. Lancet. 2010;375:2052. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60943-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hyman S, Chisholm D, Kessler R, Patel V, Whiteford HA. Mental disorders in disease control priorities in developing countries. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, editors. Disease control priorities in developing countries New York: The World Bank & Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 605-25. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chisholm D, Rehm J, Van Ommeren M, Monteiro M. Reducing the global burden of hazardous alcohol use: a comparative cost-effectiveness analysis. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65:782–93. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chisholm D, Sanderson K, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Saxena S. Reducing the global burden of depression: population-level analysis of intervention cost-effectiveness in 14 world regions. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:393–403. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.5.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chisholm D, Gureje O, Saldivia S, Villalón Calderón M, Wickremasinghe R, Mendis N, et al. Schizophrenia treatment in the developing world: an interregional and multinational cost-effectiveness analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:542–51. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.045377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Public mental health: guidelines for the elaboration and management of national mental health programmes Geneva: World Health Organization; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ferri C, Chisholm D, Van Ommeren M, Prince M. Resource utilisation for neuropsychiatric disorders in developing countries: a multinational Delphi consensus study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:218–27. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0729-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lund C, Flisher AJ, Lee T, Porteus K, Robertson BA. A model for estimating mental health service needs in South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2000;90:1019–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lund C, Flisher AJ. Norms for mental health services in South Africa. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41:587–94. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0057-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Funk M, Saraceno B, Drew N, Lund C, Grigg M. Mental health policy and plans: promoting an optimal mix of services in developing countries. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2004;33:4–16. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mental health policy and service guidance package: organization of services for mental health Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chaudhry MR. Staffing requirements. In: Baasher TA, Carstairs GM, Gier R, Hassler FR, editors. Mental health services in developing countries Geneva: World Health Organization; 1975. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/offset/WHO_OFFSET_22_(pt1-pt3).pdf [accessed 8 November 2010]. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prince M, Patel V, Saxena S, Maj M, Maselko J, Phillips MR, et al. No health without mental health. Lancet. 2007;370:859–77. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brazil, Ministry of Health, Department of Healthcare & Department of Strategic and Programmatic Actions. Proceedings of the Regional Conference on Reform of Mental Health Services: 15 years after the Caracas Declaration, Brasilia, 5–8 November 2005

- 48.Buchan J, Dal Poz MR. Skill mix in the health care workforce: reviewing the evidence. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80:575–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Planning and budgeting to deliver services for mental health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scheffler RM, Bruckner TA, Fulton BD, Yoon J, Shen G, Chisholm D et al. Human resources for mental health: workforce shortages in low and middle income countries. Human Resources for Health Observer 8. Geneva: World Health Organization (in press, February 2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Patel V. The future of psychiatry in low- and middle-income countries. Psychol Med. 2009;39:1759–62. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709005224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jacob KS, Sharan P, Mirza I, Garrido-Cumbrera M, Seedat S, Mari JJ, et al. Mental health systems in countries: where are we now? Lancet. 2007;370:1061–77. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]