Abstract

Background

There is a paucity of data on the trends in discharge disposition for patients undergoing hepatic resection for malignancy.

Aim

To analyse the national trends in discharge disposition after hepatic resection for malignancy.

Methods

The National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database was queried (1993 to 2005) to identify patients that underwent hepatic resection for malignancy and analyse the discharge status (home, home health or rehabilitation/skilled facility).

Results

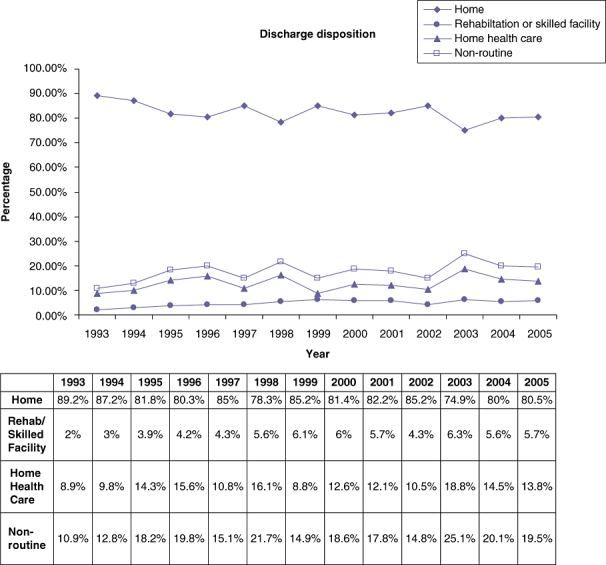

A weighted total of 74 520 patients underwent hepatic resection of whom, 53 770 patients had a principal diagnosis of malignancy. The overall mortality improved from 6.3% to 3.4%. After excluding patients that died in the post-operative period and those with incomplete discharge status, 45 583 patients were included. The proportion of patients that had acute care needs preventing them from being discharged home without assistance increased from 10.9% in 1993 to 19.5% in 2005. While there was an increase in the number of patients discharged to home health care during this time (8.9% to 13.8%), there was a larger increase in the proportion of patients that were discharged to a rehabilitation or skilled nursing facility (2% to 5.7%). Despite a decrease in the mortality rates, there was no improvement in rate of patients discharged home without assistance over the period of the study.

Conclusions

The results of the present study demonstrate that after hepatic resection, a significant proportion of patients will need assistance upon discharge. This information needs to be included in patient counselling during pre-operative risk and benefit assessment.

Keywords: hepatic resection, discharge disposition, age, co-morbidities

Introduction

Hepatic resection is increasingly performed in the United States for various malignancies involving the liver.1,2 Hepatic resection is considered to be the only modality that offers the hope of long-term survival for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer with reported 5-year survival rates ranging from 19% to 47%.3–5 Similarly, hepatic resection is a vital part of the algorithm in the treatment of patients with primary hepatic malignancies.6 Several reports with large numbers of patients have demonstrated the safety of hepatic resection with acceptable mortality rates.7–11

Despite the low mortality rates, the morbidity rates continue to remain high ranging from 14% to 54%.7–10 The presence of post-operative morbidity determines the length of stay and the final discharge disposition. It is presumed that some patients are not candidates to be discharged home because of their post-operative course. There is a paucity of data on the national trends in discharge disposition after hepatic resection for malignancy. This information is important as it needs to be included in the pre-operative counselling of risks and benefits with the patients. The aims of the present study were to: (i) analyse the national trends in discharge disposition after hepatic resection for malignancy, and (ii) determine the factors that influence the discharge disposition.

Materials and methods

The Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database was utilized to analyse the trends in discharge status after hepatic resection for malignancy. Data were obtained from the NIS database developed as part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The NIS is designed to approximate a 20% sample of US community hospitals. In 2005, the NIS data contained discharge data from 1054 hospitals located in 37 states.

The NIS database was queried (1993 to 2005) to identify patients that underwent hepatic resection for malignancy. Patients that underwent hepatic resection for benign conditions were excluded. Data on patient age and gender, admission type, hospital size and type, diagnosis, presence of pre-operative co-morbidities, race, income, extent of resection and length of stay were extracted from the database.

Co-morbid conditions were identified using the taxonomy published by Elixhauser.12 The status of patients at discharge was noted. ‘Home’ was defined as patients that were discharged home with no health assistance. ‘Rehabilitation or skilled facility’ was defined as patients that were discharged or transferred to a skilled nursing, sub-acute care or nursing facility. ‘Home health care’ was defined as patients that were discharged home but needed the assistance of a visiting nurse or other skilled health care personnel. For further analysis, ‘Rehabilitation or skilled facility’ and ‘home health care’ were grouped under ‘Non-routine’.

Statistical methods

SAS software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and SUDAAN software were used for all statistical analysis to account for the complex sampling design of NIS. Weighted sample estimates, standard errors and 95% confidence limits (CL) were calculated using the Taylor expansion method. All statistical tests were two-sided and P-values less than 0.05 are considered to be statistically significant.

Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel ANOVA-type test for trend was used to compare changes in discharge status over time. Chi-square tests were used to compare patient characteristics by discharge status throughout the entire study period. A multivariate logistic regression model was fit to predict the probability of a routine discharge with the significant variables (at the 0.01 level) in the univariate analysis as predictor variables. We also examined an additional model looking at age and number of comorbidities as a combination group variable; this model was adjusted for year, diagnosis group, procedure type and length of stay.

Results

Between 1993 and 2005, a weighted total of 74 520 patients underwent hepatic resection (lobectomy or wedge resection) as the principal procedure. Of those, 53 770 patients had a principle diagnosis of malignant neoplasm involving the liver (primary or metastatic). After excluding patients that died in the post-operative period, those that left against medical advice, and those that did not have a post-hospital disposition indicated, 45 583 patients were included in the study. The overall mortality rate showed an improvement over the period of the study from 6.3% in 1993 to 3.4% in 2005.

The discharge disposition of all included patients over the period of the study is shown in Fig. 1: a decrease in the number of patients in the ‘Home’ group by almost 10% was noted. Similarly, the proportion of patients that had acute care needs preventing them from being discharged home without assistance (‘Rehabilitation or skilled’+‘home health care’) which would be classified as non-routine increased from 10.9% in 1993 to 19.5% in 2005 (P= 0.0042) (Fig. 1). While there was an increase in the number of patients discharged to ‘home health care’ by 55% (8.9% to 13.8%) during this time, there was a larger increase in the proportion of patients that were discharged to a ‘Rehabilitation or Skilled’ facility by 185% (2% to 5.7%). Univariate analysis of the influence of various variables on the discharge disposition is shown in Table 1. The primary diagnosis, extent of resection, age, presence of pre-operative co-morbidities, race and length of stay were noted to have a statistically significant influence on the discharge disposition.

Figure 1.

Trends in discharge disposition over the period of the study

Table 1.

Univariate analysis of the influence of various factors on discharge disposition, years 1993–2005 combined

| n | Home % | Non-routine % | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extent of resection | ||||

| =lobectomy | 20 415 | 81 | 19 | 0.0089 |

| =wedge resection | 25 167 | 83 | 17 | |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| =Primary | 12 268 | 79 | 21 | <0.0001 |

| =Metastasis | 33 314 | 83 | 17 | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| <70 | 33 140 | 87 | 13 | <0.0001 |

| ≥70 | 12 442 | 69 | 31 | |

| Co- morbidities | ||||

| ≤2 | 20 147 | 87 | 13 | <0.0001 |

| ≥3 | 25 436 | 78 | 22 | |

| Size | ||||

| =Small | 3 737 | 80 | 20 | 0.78 |

| =Medium | 6 752 | 82 | 18 | |

| =Large | 35 070 | 82 | 18 | |

| Hospital | ||||

| =non-teaching | 10 184 | 82 | 18 | 0.88 |

| =teaching | 35 374 | 82 | 18 | |

| Race | ||||

| =non-white | 9 230 | 85 | 15 | 0.018 |

| =white | 28 038 | 81 | 19 | |

| Income | ||||

| =1–24 999 | 6 567 | 79 | 21 | 0.091 |

| 25 000–34 999 | 11 785 | 82 | 18 | |

| 35 000–44 900 | 10 579 | 82 | 18 | |

| 45 000 and up | 13 797 | 83 | 17 | |

| Length of stay | ||||

| ≤10 days | 35 673 | 87 | 13 | <0.0001 |

| >10 days | 9 909 | 64 | 36 | |

Non-routine: includes Rehabilitation/skilled nursing facility and home health care.

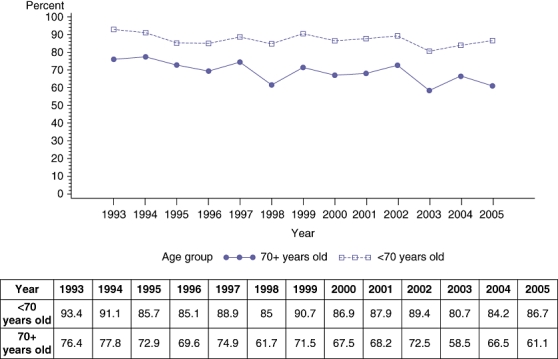

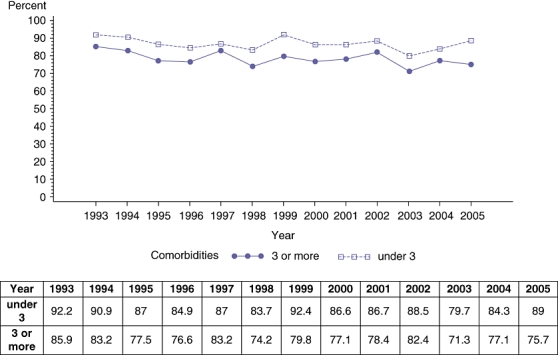

Table 2 shows the results of a multivariate logistic regression analysis of the influence of various variables on the discharge disposition. Several variables such as age, number of co-morbidities and length of stay were noted to have a significant influence on the discharge disposition. Patients with a length of stay of more than 10 days were 76% less likely to have a routine discharge (Table 2). Those greater than 70 years old were 65% less likely to have a routine discharge. Although the ‘home’ discharge rate remained the same in the less than 70 years age group, we noted a significant decrease in the older group of patients (Fig. 2). Patients with three or more co-morbidities were 32% less likely to have a routine discharge than those with less than three co-morbidities. Within the group of patients with more than three co morbidities we noted a decrease in the ‘home’ discharge rate over the period of the study (Fig. 3). The interaction between age and co-morbidities was not significant in the multivariate model (P= 0.55). Even though the interaction was not significant we created an age/co-morbidities combination variable as a predictor of ‘home’ discharge while adjusting for primary diagnosis, extent of resection and length of stay. Patients older than 70 years of age and having more than three pre-operative co-morbidities had the lowest possibility of a routine discharge (24% less likely than the reference group of <70 years and <3 co-morbidities).

Table 2.

Multivariate model of the probability of a Home discharge compared with non-routine, using a logistic regression model

| Odds Ratio | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1993 | 3.05 | 2.01 | 4.65 | <0.0001 |

| 1994 | 2.18 | 1.27 | 3.72 | ||

| 1995 | 1.33 | 0.79 | 2.25 | ||

| 1996 | 1.16 | 0.70 | 1.91 | ||

| 1997 | 1.56 | 1.02 | 2.39 | ||

| 1998 | 1.03 | 0.66 | 1.61 | ||

| 1999 | 1.50 | 0.90 | 2.51 | ||

| 2000 | 1.14 | 0.74 | 1.75 | ||

| 2001 | 1.14 | 0.77 | 1.71 | ||

| 2002 | 1.46 | 0.86 | 2.47 | ||

| 2003 | 0.71 | 0.44 | 1.17 | ||

| 2004 | 0.93 | 0.61 | 1.44 | ||

| 2005 | Ref. | – | – | ||

| Cancer Group | Primary | 0.88 | 0.76 | 1.03 | 0.10 |

| Metastases | Ref. | – | – | ||

| Procedure | Lobectomy | 0.91 | 0.80 | 1.04 | 0.19 |

| Wedge Resection | Ref. | – | – | ||

| Age group | <70 years | Ref. | – | – | <0.0001 |

| 70+ years | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.40 | ||

| Number of co-morbidities | under 3 | Ref. | – | – | <0.0001 |

| 3 or more | 0.68 | 0.59 | 0.78 | ||

| Length of stay | 10 days or less | Ref. | – | – | <0.0001 |

| More than 10 days | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.29 | ||

Presented are odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Figure 2.

Rate (percentage) of ‘home’ discharge based on age

Figure 3.

Rate (percentage) of ‘home’ discharge based on presence of co-morbidities

An analysis of numerical trends of the significant variables (age and co-morbidities), demonstrated a slight change in the age distribution over the period of the study, with a decrease in the proportion of older age patients (Table 3). In contrast, the study noted a larger increase in the proportion of patients with greater than three co morbidities (48% in 1993 to 64% in 2005).

Table 3.

Trends in the number of patients based on age and presence of co-morbidities (1993–2005)

| Year | Age (years) | Co-morbidities | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <70 years old | 70+ years old | 3 or more | under 3 | |

| 1993 | 75.03% | 24.97% | 48.41% | 51.59% |

| 1994 | 70.79% | 29.21% | 47.94% | 52.06% |

| 1995 | 69.36% | 30.64% | 54.72% | 45.28% |

| 1996 | 68.62% | 31.38% | 55.93% | 44.07% |

| 1997 | 72.22% | 27.78% | 52.96% | 47.04% |

| 1998 | 71.01% | 28.99% | 57.21% | 42.79% |

| 1999 | 71.22% | 28.78% | 57.11% | 42.89% |

| 2000 | 71.44% | 28.56% | 54.61% | 45.39% |

| 2001 | 71.41% | 28.59% | 53.69% | 46.31% |

| 2002 | 75.14% | 24.86% | 55.13% | 44.87% |

| 2003 | 74% | 26% | 57.45% | 42.55% |

| 2004 | 75.6% | 24.4% | 61.27% | 38.73% |

| 2005 | 75.76% | 24.24% | 64.07% | 35.93% |

Discussion

The results of the present study show that fewer patients are being discharged home after hepatic resection for malignancy. Of the patients that were not discharged home we noted a significant increase in the number of patients being discharged to Rehabilitation or skilled facilities during the study period. This is despite the fact that there is a noted improvement in the mortality rates over the period of the study.

The significant factors shown to have an influence on the discharge disposition are age, pre-operative co-morbidities and length of stay. Several reports have demonstrated the safety of hepatic resection in the elderly.13–15 These reports documented mortality and morbidity rates that were similar to younger patients.13–15 Although the mortality rate in the present study is in the currently acceptable range, we noted that older patients are less likely to go home directly and this trend increased throughout the time period of the study. This is despite the finding of a slight decrease in the proportion of hepatic resections performed in the older age group during the period of the study (Table 3). The reasons for this are unclear but it is likely that although the elderly have equivalent immediate peri-operative outcomes, a prolonged recovery period or possibly greater complications or co-morbidities prevent them from going home. A recent 20-year multicentre Italian Liver group experience concluded that the overall applicability of radical or effective hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) treatments was unaffected by old age but they did notice a trend that patients older than 70 years are now offered more percutaneous treatments than hepatic resection or transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE).16

Similarly, it is well known that the presence of pre-operative co-morbidities can have an influence on post-operative outcomes and thereby the discharge disposition.7,8 A prospective study of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) data identified pre-operative factors such low serum albumin, serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT) > 40 units/l, previous cardiac operation, and severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) would increase post-operative morbidity after liver resection.17 The same study identified male gender, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class III or higher, presence of ascites, dyspnoea and severe COPD as factors influencing mortality.17 Similarly, a recent analysis of NSQIP patients that underwent hepatic resection documented a mortality and morbidity rate of 2.5% and 19.6%, respectively.11 They identified several co-morbidities such as nutritional status, liver function and extent of hepatic resection that had an influence on post-operative outcome. An adverse post-operative outcome is likely to have a bearing on the discharge disposition.11 The present study demonstrated that although we are operating on the same percentage of older patients, there was a noted increase in the number of patients with greater than three co-morbidities (Table 3). This trend may be contributing to a decrease in the rate of patients being discharged to ‘home’ and an increase in the need for rehabilitation or a skilled facility to recuperate after a major hepatic resection. The group with the least chance of going home was patients older than 70 years of age and the concomitant presence of three or more pre-operative co-morbidities (Table 2).

The length of stay was also noted to be longer in patients in the ‘non-routine’ group. It is well known that length of stay correlates with post-operative course/complications and can therefore influence discharge disposition. The NSQIP analysis of 2313 elective open hepatic resections documented that patients with a post-operative major morbidity had a longer median length of stay (10 vs. 6 days, P= 0.001) and higher mortality rate (11.3% vs. 0.3%; P= 0.001).11

There are several limitations to a study of this nature. The NIS database does not provide for detailed analysis of post-operative complications. The type and severity of post-operative complications can have a significant bearing on the discharge disposition. It is possible that analysis of post-operative complications can help in identifying the sub-group of patients that are less likely to be routinely discharged. The NIS database does not contain information regarding administration of chemotherapy. Various authors have noted that pre-operative chemotherapy can cause sinusoidal congestion18 and steatohepatitis19 and these changes can have an adverse influence on post-operative outcomes.20,21 Kooby et al.22 demonstrated the adverse influence of hepatic steatosis on morbidity after hepatic resection. The advent of modern chemotherapy has led to an increase in the utilization of the newer drugs5 for patients with advanced colorectal cancer. It is likely that the increasing utilization of chemotherapy may contribute to post-operative complications that can affect the discharge disposition. Lastly, the current state of health care in the United States places an emphasis on discharging patients as soon as possible from an acute care setting. This is in contrast to health policies several years ago when patients stayed in the hospital until they were fit to be discharged home. This change in discharge planning may also confound the results of our retrospective study.

The present study did not analyse the outcomes pertaining to patients that underwent minimally invasive hepatic resection. It is well known that minimally invasive hepatectomy is safe, feasible and associated with comparable or better peri-operative outcomes.23,24 It is likely that the discharge disposition can be influenced in the future by the increasing number of minimally invasive hepatic resections.

The relevance of the present study results is that it provides a temporal trend to a type of outcome that is not widely reported. These data are important for other reasons as well as assessing the overall cost of healthcare that goes beyond the analysis of the immediate operative and perioperative utilization of resources. It is likely that patients that do not go home incur a differential pattern of health care expenses and this needs to be conveyed to the patients. Unlike the length of stay, factors such as age, co-morbidities, diagnosis and type of resection are usually known pre-operatively. The likelihood of being discharged to home based on the presence or absence of the above factors needs to be included in the pre-operative counselling of the risks and benefits of the proposed hepatic resection.

In summary, despite a declining mortality rate, the results of the present study demonstrated a decrease in the number of patients being discharged home after hepatic resection for malignancy. Further studies to analyse the contributing factors in detail are essential but some risk factors include age greater than 70 years, presence of three or more co-morbidities and an increased post-operative length of stay. This information needs to be included in the pre-operative counselling of the individual patient and is also important in the broader context of assessing health care costs and resource utilization.

Conflicts of interest

No financial support received and no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Dimick JB, Cowan JA, Jr, Knol JA, Upchurch GR., Jr Hepatic resection in the United States: indications, outcomes and hospital procedural volumes from a nationally representative database. Arch Surg. 2003;138:185–191. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dimick JB, Wainess RM, Cowan JA, Upchurch GR, Jr, Knol JA, Colletti LM. National trends in the use and outcomes of hepatic resection. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Jong MC, Pulitano C, Ribero D, Strub J, Mentha G, Schulick RD, et al. Rates and patterns of recurrence following curative intent surgery for colorectal liver metastasis: an international multi-institutional analysis of 1669 patients. Ann Surg. 2009;250:440–448. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b4539b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomlinson JS, Jarnagin WR, DeMatteo RP, Fong Y, Kornprat P, Gonen M, et al. Actual 10-year survival after resection of colorectal metastasis defines cure. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4575–4580. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.0833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kopetz S, Chang GJ, Overman MJ, Eng C, Sargent DJ, Larson DW, et al. Improved survival in metastatic colorectal cancer is associated with adoption of hepatic resection and improved chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3677–3683. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nathan H, Raut CP, Thornton K, Herman JM, Ahuja N, Schulick RD, et al. Predictors of survival after resection of early hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2009;249:799–805. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181a38eb5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jarnagin WR, Gonen M, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP, Ben-Porat L, Little S, et al. Improvement in perioperative outcome after hepatic resection: analysis of 1803 consecutive cases over the last decade. Ann Surg. 2002;236:397–406. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000029003.66466.B3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imamura H, Seyama Y, Kokudo N, Maema A, Sugawara Y, Sano K, et al. One thousand fifty-six hepatectomies without mortality in 8 years. Arch Surg. 2003;138:1198–1206. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.11.1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fan ST, Lo CM, Liu CL, Lam CM, Yuen WK, Yeung C, et al. Hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: toward zero hospital deaths. Ann Surg. 1999;229:322–330. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199903000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang ZQ, Xu LN, Yang T, Zhang WZ, Huang XQ, Cai SW, et al. Hepatic resection: an analysis of the impact of operative and perioperative factors on morbidity and mortality rates in 2008 consecutive hepatectomy cases. Chin Med J. 2009;122:2268–2277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aloia TA, Fahy BN, Fischer CP, Jones SL, Duchini A, Galati J, et al. Predicting poor outcomes following hepatectomy: analysis of 2313 hepatectomies in the NSQIP database. HPB (Oxford) 2009;11:510–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2009.00095.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, Coffey RM. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adam R, Frilling A, Elias D, Laurent C, Ramos E, Capussotti L, et al. Liver resection of colorectal metastases in elderly patients. Br J Surg. 2010;97:366–376. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brand MI, Saclarides TJ, Dobson HD, Millikan KW. Liver resection for colorectal cancer: liver metastases in the aged. Am Surg. 2000;66:412–415. discussion 415–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sgourakis G, Sotiropoulos GC, Bockhorn M, Fouzas I, Radtke A, Molmenti EP, et al. Major liver resections for primary liver malignancies in the elderly. Acta Chir Belg. 2009;109:340–344. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2009.11680436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mirici-Cappa F, Gramenzi A, Santi V, Zambruni A, Di Micoli A, Frigerio M, et al. Treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma in elderly patients are as effective as in younger patients: a 20-year multicentre experience. Gut. 2010;59:387–396. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.194217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Virani S, Michaelson JS, Hutter MM, Lancaster RT, Warshaw AL, Henderson WG, et al. Morbidity and mortality after liver resection: results of the patient safety in surgery study. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:1284–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.02.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubbia-Brandt L, Audard V, Sartoretti P, Roth AD, Brezault C, Le Charpentier M, et al. Severe hepatic sinusoidal obstruction associated with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:460–466. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernandez FG, Ritter J, Goodwin JW, Linehan DC, Hawkins WG, Strasberg SM. Effect of steatohepatitis associated with irinotecan or oxaliplatin pretreatment on resectability of hepatic colorectal metastases. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200:845–853. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2005.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris-Stiff G, Tan YM, Vauthey JN. Hepatic complications following preoperative chemotherapy with oxaliplatin or irinotecan for hepatic colorectal metastases. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:609–614. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.07.007. Epub 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdalla EK, Vauthey JN. Chemotherapy prior to hepatic resection for colorectal liver metastases: helpful until harmful? Dig Surg. 2008;25:421–429. doi: 10.1159/000184733. Epub 2009 Feb 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kooby DA, Fong Y, Suriawinata A, Gonen M, Allen PJ, Klimstra DS, et al. Impact of steatosis on perioperative outcome following hepatic resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:1034–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen KT, Gamblin TC, Geller D. World review of laparoscopic liver resection – 2804 patients. Ann Surg. 2009;250:831–841. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b0c4df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lai EC, Tang CN, Ha JP, Li MK. Laparoscopic liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: ten-year experience in a single center. Arch Surg. 2009;144:143–147. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2008.536. discussion 148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]