Abstract

The formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the change of the intracellular pH (pHi) are common phenomena during apoptosis. How they are interconnected, however, is poorly understood. Here we show that numerous anticancer drugs and cytokines such as Fas ligand and tumour necrosis factor α provoke intracellular acidification and cause the formation of mitochondrial ROS. In parallel, we found that the succinate:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (SQR) activity of the mitochondrial respiratory complex II is specifically impaired without affecting the second enzymatic activity of this complex as a succinate dehydrogenase (SDH). Only in this configuration is complex II an apoptosis mediator and generates superoxides for cell death. This is achieved by the pHi decline that leads to the specific dissociation of the SDHA/SDHB subunits, which encompass the SDH activity, from the membrane-bound components of complex II that are required for the SQR activity.

Keywords: apoptosis, mitochondria, respiratory chain, complex II, ROS

Intracellular acidification is, besides cell shrinkage, membrane blebbing, DNA fragmentation, and phosphatidylserine exposure, a commonly described phenomenon during the apoptotic process. It constitutes an early event during apoptosis and precedes mitochondrial dysfunction.1 A wide variety of apoptosis signals can cause this pH drop, typically in the range of 0.3–0.4 pH units, such as UV-irradiation, death receptor triggering, growth factor deprivation, and anticancer compounds, and also genes such as p53 and Bax activation.1, 2, 3 This can be accomplished by modulating the activity of plasma membrane transporters such as the alkalinising transporter Na+/H+ exchanger 1 (NHE1), which seems to be inhibited during apoptosis.1 Although it has been suggested that the pH change can contribute to caspase activation,4 exactly how pH changes are linked to more downstream signals during apoptosis induction is only poorly understood.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are long known as general mediators of apoptosis. Mitochondria are regarded as the main, but not the sole source for ROS.5 Although complex I and III have long been recognised as supplying ROS for apoptosis,6 in recent years complex II has also been established as an efficient producer of ROS, particularly superoxides, for apoptosis induction.7 Sensitive detection methods indicated that it can surpass even complex III for ROS formation.8 Structural studies likewise indicate that complex II can produce ROS.9 However, the exact mechanism by which complex II generates ROS in response to apoptosis signals remains unknown.

With only four subunits, complex II is the smallest protein complex of the mitochondrial respiratory chain and the only complex to be fully encoded by nuclear DNA.10 The SDHC and SDHD proteins form the membrane-anchoring components, which associate with two subunits facing the mitochondrial matrix: SDHB, an Fe-S protein, and SDHA, a FAD-containing protein11 (Supplementary Figure 1a). Complex II is also a component of the Krebs cycle with its succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) activity oxidising the metabolite succinate to fumarate. The electrons generated in this reaction are then channelled in a not completely understood pathway within complex II to ubiquinone, which is reduced to ubiquinol by the succinate:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (SQR) activity of complex II. Finally, the reduction equivalents are shuttled to complex III in the respiratory chain.12

Here we demonstrate that various compounds and cytokines cause an intracellular pH (pHi) acidification and ROS formation during apoptosis. We found that these prominent features of apoptosis are linked by the specific inhibition of complex II.

Results

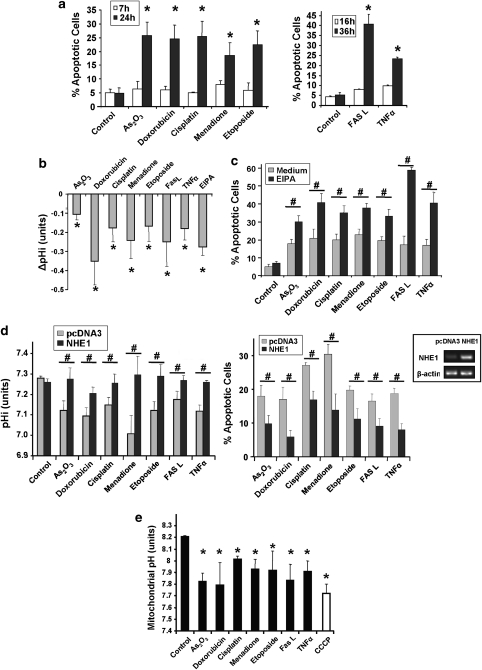

Early intracellular acidification and ROS formation during apoptosis

We set up a suitable cellular system to study the early events of apoptosis signalling. At 7 h after addition of various anticancer agents, HeLa cells showed no signs of apoptosis induction such as nuclear DNA degradation (Figure 1a) or phenotypic changes (not shown). However, after 24 h, these drugs at the concentrations used caused apoptosis as evidenced by an increase of the sub-G1 cell population. The Fas ligand (FasL) and tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α) cytokines exerted a delayed effect on apoptosis with only a marginal sub-G1 cell population at 16 h but a substantial apoptosis after 36 h (Figure 1a). An additional assay for caspase-3 activity and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) cleavage confirmed apoptosis induction (Supplementary Figure 2). When we measured pHi 8 h after treatment and before apoptosis, we observed a pHi decrease with all pro-apoptotic signals used (Figure 1b). EIPA, an inhibitor of the alkalinising transporter NHE1 used as an acidification control, markedly potentiated apoptosis in co-treatments with all agents (Figure 1c). Conversely, when we transiently overexpressed NHE1, we prevented acidification following drug and cytokine treatment and strongly reduced apoptosis (Figure 1d). We were also able to show that the mitochondrial matrix acidified in parallel with the cytosolic pHi drop (Figure 1e).

Figure 1.

pH change during apoptosis. (a) Apoptosis induction by anticancer drugs and cytokines. HeLa cells were treated with the indicated drugs for 7 and 24 h or exposed to FasL or TNF-α for 16 and 36 h (see Materials and Methods). After treatment, apoptotic cells were quantified by flow cytometry using PI staining of the sub-G1 population. *P<0.05 compared with the related control. (b) The pro-apoptotic agents lead to cytosolic acidification. HeLa cells were treated for 7 h with the indicated drugs or cytokines. EIPA (20 μM), an inhibitor of NHE1, was used as a positive control for cytosolic acidification. Cells were collected and incubated with the pH-sensitive fluorescent probe carboxy-SNARF-1. pH-related fluorescence ratios were analysed by flow cytometry and converted into pH values. Results are normalised to pHi in untreated cells and expressed as ΔpHi values. *P<0.05 compared with pHi in untreated cells. (c) Inhibition of the NHE1 transporter by EIPA potentiates the apoptosis induced by the pro-apoptotic agents. HeLa cells were treated for 26 h with the anticancer drugs or cytokines in the presence or absence of 20 μM EIPA. Apoptosis was measured as in (a). #P<0.05. (d) Overexpression of NHE1 reduces cell death induced by the various pro-apoptotic signals and inhibits cytosolic acidification. HeLa cells were transfected either with pcDNA3 or with a NHE1 expression plasmid. After 48 h, when the NHE1 mRNA level was upregulated (see inset), the cells were treated with the anticancer drugs or cytokines. Changes in pHi (left panel) were quantified by flow cytometry after a 7-h treatment, as in (b). Apoptosis (right panel) was measured after 26 h as in (a). Results are shown after subtraction of the pcDNA3-associated apoptosis background. #P<0.05. (e) The different pro-apoptotic agents responsible for complex II inhibition lead to mitochondrial matrix acidification. HeLa cells were co-transfected for 24 h with a mt-EYFP plasmid, sensitive to pHM changes, and with a mt-dsRed plasmid (insensitive). Cells were treated for 7 h with the different anticancer drugs or cytokines. CCCP (10 μM for 20 min), a mitochondrial protonophore, was used as a positive control for mitochondrial matrix acidification. pHM-related fluorescence ratios were analysed by flow cytometry (see Materials and Methods) and converted into pHM values. *P<0.05 compared with control

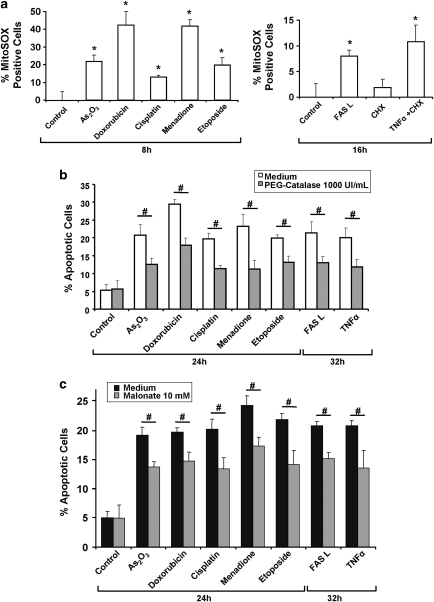

We then studied whether ROS could be causative for apoptosis triggered by the compounds shown in Figure 1. Using the dihydroethidium (DHE) probe (Supplementary Figure 3a) and the mitochondria-specific probe MitoSOX (Figure 2a), we confirmed that all these agents could elicit the formation of ROS at 8 or 16 h after their application. Different efficiencies in ROS generation were noticed, probably because some compounds can induce ROS formation through additional pathways.13, 14 Moreover, we showed that pre-treatment with PEG catalase, a cell-permeable form of catalase,15 could reduce their potential to induce apoptosis, underlining the fundamental role of ROS in the apoptotic cascade (Figure 2b). We also demonstrated that acidification impairment through NHE1 overexpression markedly reduced drug-induced mitochondrial ROS production (Supplementary Figure 3b). Finally, as our previous work showed a role of complex II in ROS production and apoptosis,16 we used the SDH inhibitor malonate and observed a reduction of apoptosis induced by all compounds, suggesting that complex II-dependent ROS accumulation is at least partly responsible for apoptosis induction (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Involvement of ROS in apoptosis induced by various apoptotic signals. (a) Effects of the different anticancer drugs and cytokines on mitochondrial ROS production. HeLa cells were treated with the indicated drugs (8 h) or cytokines (16 h), at the concentrations shown in Supplementary Table 1. ROS were quantified by flow cytometry through MitoSOX-related fluorescence. (b, c) Effects of the ROS scavenger PEG-catalase (b) and the SDH inhibitor malonate (c) on apoptosis induced by the different agents. HeLa cells were treated with the compounds for the indicated times and apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry using PI staining of the sub-G1 population. *P<0.05 compared with the related control; #P<0.05

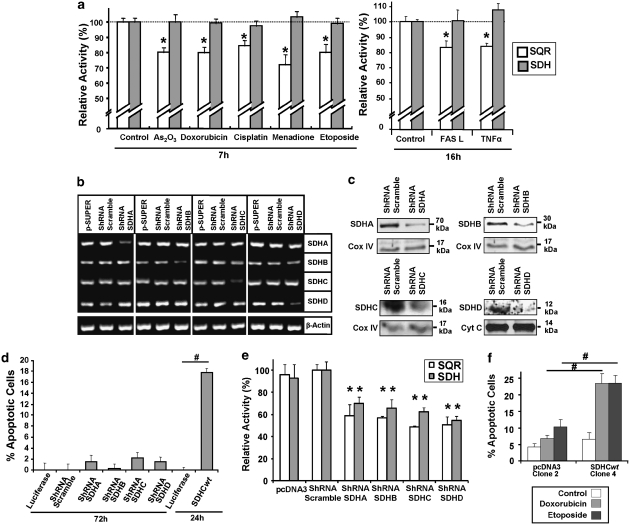

Specific inhibition of complex II for apoptosis induction

On the basis of our previous work16 and the results with the complex II inhibitor malonate (Figure 2c), we investigated the effects of the apoptosis inducers on complex II in more detail with two assays classically used for the enzymatic activities of complex II (described in Supplementary Figure 1b and c). We found that at 7 h (anticancer drugs) and 16 h (cytokines) after treatment, the SDH activity of complex II was not compromised, whereas its SQR activity was inhibited by ∼20% (Figure 3a). Thus, we hypothesised that complex II contributes to apoptosis induction only when the SQR activity is inhibited while the SDH activity is still fully functioning, creating an uncoupling phenomenon at the complex II level. This model, however, seemed to be in conflict with the discovery in cancer cells with inactivating mutations in the complex II membrane anchoring subunits SDHC and SDHD17 that appear to lead to apoptosis resistance and tumour formation rather than cell death induction. Consequently, we set up experiments to test the consequences on the SQR and SDH activity and on apoptosis induction upon specific disruption of the various complex II subunits by shRNA constructs. Figure 3b shows that the mRNAs of all targeted complex II components were reduced after 72 h, whereas the mRNA expression levels of their associated subunits remained unaffected. We also confirmed the downregulation of the respective proteins by western blot (Figure 3c). Our expectation was that we detect apoptosis when the membrane-bound subunits are downregulated but not then the peripheral components of complex II were targeted. However, we did not observe any apoptosis induction following a 72-h transfection with these shRNA (Figure 3d). When we measured the enzymatic activities of complex II, we found that both SDH and SQR activity were markedly and equally downregulated when SDHA and SDHB were targeted, and also when SDHC and SDHD were inhibited (Figure 3e). This seems to be due to a major impairment of the whole complex assembly in the mitochondria (Supplementary Figure 4). When we targeted SDHC, SDHD, or SDHB, all the other subunits were likewise reduced in the mitochondria, except SDHA. Hence, inactivation of complex II subunits as observed in cancer cells could impair the whole complex II and, consequently, the association of an active SDH activity with an inhibited SQR function is not possible, rendering complex II incapable of apoptosis induction and promoting tumourigenesis. To further prove that the observed effects depend on complex II, we made use of SDHC−/− and wild-type (wt) SDHC-reconstituted B9 cells.18, 19 Stable clone 4 expressed the SDHC transgene at a level comparable to that of the parental wt B1 cells (Supplementary Figure 5a). We found that by expressing wt SDHC (clone 4) we could restore both SDH and SQR activity to a similar level than in parental B1 cells (Supplementary Figure 5b). Importantly, complex II-reconstituted cells were also re-sensitised to apoptosis induction by anticancer drugs (Figure 3f). Thus, on the basis of all these findings, we hypothesised that complex II contributes to apoptosis induction when functional complex II aggregates become inactive for the SQR activity, whereas the SDH function is still fully effective. Although this cannot happen in tumour cells with complex II-inactivating mutations, in wt cells it creates uncoupling at the complex II level leading to ROS production and subsequent apoptosis.

Figure 3.

Effect of various anticancer drugs and cytokines and the shRNA-mediated downregulation on the enzymatic activities of complex II. (a) Effects of the various pro-apoptotic signals on the SQR and SDH activities of complex II. HeLa cells were treated with the indicated drugs (7 h) or cytokines (16 h). Mitochondria were isolated and SQR and SDH activities were assessed by the appropriate assay. *P<0.05 compared with the related control. (b, c) Downregulation of SDHA/B/C/D mRNA (b) and proteins (c) by shRNA. HeLa cells were transfected with an empty pSuper vector, a scrambled pSuper-shRNA or shRNA constructs targeting SDHA/B/C/D. After 72 h, mRNA levels (b) of the various complex II subunits were quantified by RT–PCR. Proteins levels (c) were analysed by western blot in mitochondrial fractions. Equal gel loading and transfer efficiency were checked with anti-Cox IV or Cyt C antibodies. (d) ShRNA-mediated downregulation of SDHA/B/C/D does not induce apoptosis. HeLa cells were transfected either with a luciferase vector, a scrambled shRNA or a specific SDHA/B/C/D shRNA. After 72 h, apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry using PI staining of the sub-G1 population. A wt SDHC expression vector was transfected as a positive control for apoptosis induction after 24 h. The same amount of a GFP plasmid was introduced in parallel to normalise the cell death induction to the transfection efficiency. Results are shown after subtraction of the luciferase-associated apoptosis background. #P<0.05. (e) Potent inhibition of SQR and SDH activity by shRNA-mediated downregulation of SDHA/B/C/D. SQR and SDH activities of complex II were measured in mitochondrial fractions isolated 72 h after transfection. Shown are the activities relative to the scrambled shRNA-transfected cells. *P<0.05 compared with the related scrambled shRNA-activity. (f) Reconstitution of SDHC expression in B9 cells sensitises cells for apoptosis. PcDNA3 clone 2 (control cells stably transfected with an empty pcDNA3 vector) and wt SDHC clone 4 (stably reconstituted cells) were treated with the indicated anticancer drugs for 48 h, at the concentrations shown in the Supplementary Table 1. Apoptosis was quantified as in (d). #P<0.05

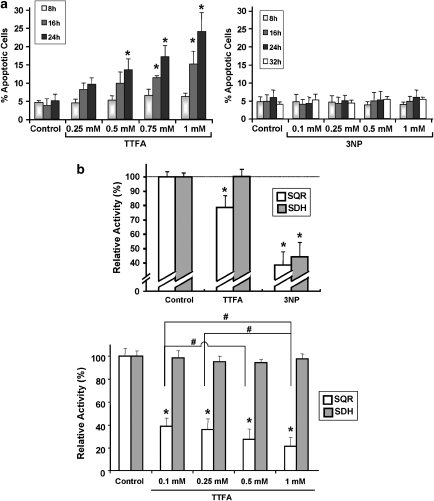

In order to assess the cellular consequences of a selective and partial SQR inhibition as observed in Figure 3a, we turned to complex II inhibitors, which facilitate a specific, concentration-dependent attenuation of complex II activities: 3-nitroproprionic acid (3NP), a succinate analogue, binds to the active site of SDHA and inhibits complex II irreversibly.11 Thenoyltrifluoroacetate (TTFA) inhibits a later step of the electron flow as it binds to the ubiquinone docking sites and abrogates the transfer of electrons to this molecule.11 Apoptosis assays revealed that 3NP did not elicit an apoptotic effect at the concentrations tested, whereas TTFA caused a time- and dose-dependent increase of apoptosis (Figure 4a). In line with the known specificity of these compounds, we have observed an inhibition of both, SQR and SDH activity, with 3NP, while TTFA reduced only the SQR activity, before apoptosis (Figure 4b, upper panel). Of note, 0.5 mM TTFA, which caused apoptosis (Figure 4a), diminished the SQR activity by 20%, a reduction also observed with the pro-apoptotic compounds (Figure 3a). An in vitro dose-escalation experiment on isolated mitochondria confirmed the concentration-dependent SQR inhibition by TTFA (Figure 4b, lower panel).

Figure 4.

Effect of TTFA and 3NP, two complex II inhibitors with different target specificities. (a) Time- and dose-dependent pro-apoptotic effects by TTFA or 3NP. HeLa cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of TTFA or 3NP. After incubation, apoptotic cells were quantified by flow cytometry using PI staining of the sub-G1 population. (b) Effects of TTFA and 3NP on SQR and SDH activities. (Top panel) HeLa cells were treated for 8 h with TTFA (0.5 mM) or 3NP (1 mM). Mitochondria were isolated and SQR and SDH activities were assessed by specific assays. (Bottom panel) Isolated mitochondria were treated by the indicated concentrations of TTFA immediately before the appropriate enzymatic assay. *P<0.05 compared with the related control; #P<0.05

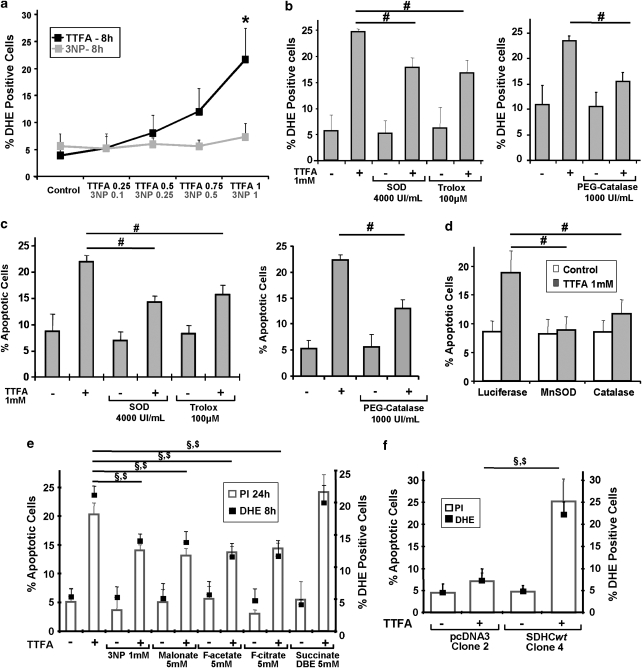

Apoptosis signals are mediated through complex II-dependent ROS production

On the basis of the above experiments, which highlight the importance of an inhibited SQR activity without SDH impairment for apoptosis induction, we speculated that if electrons provided by succinate oxidation could not efficiently be transferred to ubiquinone, they would leak out from complex II, generate ROS, and eventually trigger apoptosis. Using DHE, we found that after an 8-h treatment and before apoptosis, ROS were rapidly generated by TTFA in a dose-dependent manner. The 3NP, on the contrary, did not show ROS production at all doses used at this early time point (Figure 5a). With MitoSOX, we also demonstrated that TTFA-induced ROS had a mitochondrial origin (Supplementary Figure 3c). Pre-treatment with antioxidant enzymes (PEG-catalase and superoxide dismutase (SOD)) or ROS quenchers (Trolox) could reduce TTFA-induced ROS production and likewise apoptosis (Figure 5b and c). In addition, the transfection of plasmids coding for catalase and for mitochondrial manganese SOD (MnSOD) also potently diminished TTFA-induced apoptosis (Figure 5d). These results suggested that complex II, if specifically inhibited, can function as a source for ROS and apoptosis induction. ROS are known to also cause the passive cell death of necrosis.20 Hence, to examine whether the observed cell death was apoptosis, we analysed specific features of apoptosis, such as caspase-3 activity and PARP cleavage, and found that both of them increased upon TTFA treatment (Supplementary Figure 2).

Figure 5.

Role of ROS in apoptosis induced by specific complex II inhibition. (a) Dose-dependent ROS production induced by complex II inhibitors. HeLa cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of TTFA or 3NP for 8 h. The superoxide-sensitive dye DHE was incubated with the cells and fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry. *P<0.05 compared with the related control. (b, c) ROS scavengers reduce superoxide generation (b) and apoptosis (c) in response to specific complex II inhibition. HeLa cells were pre-treated with superoxide dismutase (SOD, 4000 UI/ml), Trolox (100 μM) or PEG-catalase (1000 UI/ml), and exposed to 1 mM TTFA for 20 h. ROS were determined as in (a) and apoptosis was measured by flow cytometry using PI staining of the sub-G1 population. #P<0.05. (d) Expression plasmids for MnSOD and catalase can reduce apoptosis by TTFA. Vectors containing luciferase, MnSOD or catalase were transfected into HeLa cells. In parallel the same amount of a GFP plasmid was transfected to normalise the cell death inhibition to the transfection efficiency. After 24 h, cells were treated by 1 mM TTFA for 8 h. Apoptosis was measured as in (c). #P<0.05. Luciferase expression had no effect on apoptosis (Supplementary Figure 10). (e) Effects of different SDH inhibitors (3NP, malonate), Krebs cycle inhibitors (fluorocitrate, fluoroacetate), or a Krebs cycle intermediate (succinate DBE) on apoptosis and ROS production induced by TTFA. HeLa cells were treated with 1 mM TTFA and the indicated compounds. As a control the inhibitors were used in their own. ROS and apoptosis were quantified as in (a) and (c), respectively. §P<0.05 for PI values; $P<0.05 for DHE values. (f) Effects of TTFA on the SDHC−/− clone 2 and on the wt SDHC reconstituted clone 4. These B9 clones were treated with 1 mM TTFA for 48 h. ROS and apoptotic cells were measured as in (a) and (c), respectively. §P<0.05 for PI values; $P<0.05 for DHE values

We also performed propidium iodide (PI) and annexin V (AV) double staining and found that necrotic PI+/AV− cells only marginally accumulated upon TTFA treatment (Supplementary Figure 6a) in contrast to PI−/AV+ apoptotic cells. PI+/AV+ double-stained necrotic or late-apoptotic cells significantly increased in response to TTFA. Nevertheless, the cell populations positive in sub-G1 (apoptotic) or 7-aminoactinomycin D (7-AAD) (necrotic and late apoptotic) assays could potently be reduced by zVAD-fmk, a pan-caspase inhibitor (Supplementary Figure 6b and c). We hypothesised that, if the TTFA pro-apoptotic effects are due to specific inhibition of complex II at the SQR level, upstream inhibitors of complex II such as those of the Krebs cycle (fluoroacetate, fluorocitrate) or of the SDH activity (3NP, malonate), would also reduce TTFA-induced ROS formation and apoptosis. Figure 5e reveals that all the upstream inhibitors of complex II reduced both ROS and apoptosis in TTFA-treated cells. Hence, these results, summarised in Supplementary Figure 7, suggested that specific complex II inhibition contributed to pro-apoptotic ROS formation through electron leakage between the SDH activity, which is linked to the Krebs cycle, and the SQR activity, as part of the respiratory chain. Also, in contrast to pcDNA3-transfected cells, SDHC-reconstituted B9 cells were again able to produce ROS and undergo apoptosis when treated with TTFA (Figure 5f) confirming the specificity of our observed effects for complex II.

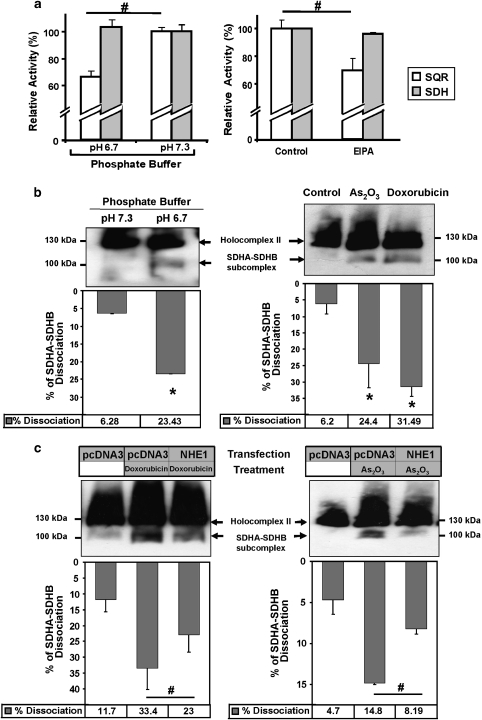

pH change leads to specific disintegration of complex II

We tested both complex II activities in the mitochondria kept in buffers with reduced pH in vitro, and observed a reduction in the SQR activity while the SDH activity remained unchanged (Figure 6a, left panel). Cytosolic acidification imposed on cells by EIPA also triggered a reduction of the SQR activity without affecting the SDH activity (Figure 6a, right panel). To explain at a molecular level the observed different enzymatic activities of complex II during apoptosis, we investigated the integrity of this protein aggregate. We separated mitochondrial proteins in a blue native gel after incubating these organelles in a phosphate buffer with normal or reduced pH. A western blot for SDHA revealed an additional band indicating the dissociation of the 100 kDa SDHA/B subcomplex, which is exposed to the mitochondrial matrix, from the integral membrane protein SDHC and SDHD (Figure 6b, left panel). This partial complex II dissociation is correlated with the partial loss of the enzymatic activity of SQR. The emergence of the SDHA/B subcomplex was likewise apparent when intact HeLa cells were treated for 7 h with As2O3 or doxorubicin and total protein extracts separated on a blue native gel (Figure 6b, right panel). The same dissociation pattern was also observed in human 293T cells (Supplementary Figure 8). Moreover, inhibition of acidification by NHE1 overexpression in HeLa cells significantly reduced the partial dissociation of complex II after drug treatment (Figure 6c).

Figure 6.

Specific complex II disintegration by pH change. (a) Effects of pHi acidification and NHE1 inhibition on complex II enzymatic activities. (Left panel) Isolated mitochondria were incubated in a phosphate buffer at normal pH 7.3 or acidic pH 6.7 and the appropriate assay was performed. (Right panel) HeLa cells were treated for 7 h with EIPA (20 μM), mitochondria were isolated, and SQR and SDH activities were assessed by specific enzymatic assays. #P<0.05. (b) Integrity of complex II as revealed by immunoblots of blue native PAGE. (Left panel) Isolated mitochondria from HeLa cells were incubated in phosphate buffers with the indicated pH for 30 min and complex II solubilisation was performed as described in Materials and Methods. (Right panel) HeLa cells were incubated for 7 h with 10 μM As2O3 or 1.4 μM doxorubicin. Whole-cell lysates were prepared and their proteins solubilised as described in Materials and Methods. Equal amounts of protein were loaded onto a native gel, blotted onto a membrane, which was probed for SDHA. (c) Overexpression of NHE1 reduces drug-induced complex II dissociation. HeLa cells were transfected either with pcDNA3 or with a NHE1 expression plasmid. After 24 h, the cells were treated with 1.4 μM doxorubicin (left panel) or 10 μM As2O3 (right panel) for 7 h. Proteins from whole-cell lysates were processed as in (b) and loaded onto a native gel. For (b) and (c), the percentage of SDHA/B subcomplex dissociation was determined using densitometric analyses of at least four independent experiments and shown as graphs under the related blots. *P<0.01 compared with the related control; #P<0.01

Discussion

pH changes cause specific inhibition of complex II

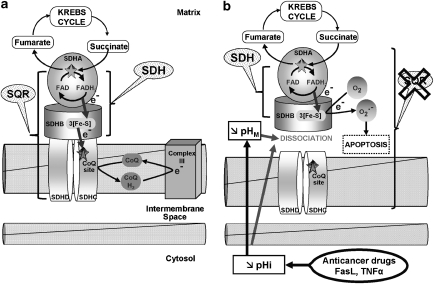

The mitochondria contain a number of master regulators for apoptosis. We have proposed that complex II of the respiratory chain constitutes such a mitochondrial factor for apoptosis control. In a previous study, we showed that defects in complex II rendered cells resistant to apoptosis induction by a wide array of pro-apoptotic signals.16 Additional independent studies also implicate complex II as an important sensor that is used by various signals for apoptosis induction. SDHD downregulation by RNAi, for example, was shown to protect neuronal cells against apoptosis by NGF withdrawal.21 Moreover, complex II inhibition by transfecting an SDHC mutant for the ubiquinone-binding site induced apoptosis.7 In this study, we addressed why complex II constitutes a major target in pro-apoptotic signalling and the mechanism of this process. Our results show that various anticancer compounds and pro-apoptotic cytokines are able to inhibit complex II specifically at the SQR level, which is responsible for ubiquinone reduction and links complex II with the respiratory chain. At the same time, the upstream SDH activity, which is associated with succinate oxidation and hence with the Krebs cycle, is not impaired. We provide evidence that this is accomplished through intracellular acidification, concomitant with mitochondrial pH decrease. This pHi drop appeared to be a synchronic event in the whole HeLa cell population, as shown by the flow cytometry density blots depicted in Supplementary Figure 9. As pHi decline is a general phenomenon during apoptosis,1 it could explain the ubiquitous involvement of complex II in apoptosis induction. Accordingly, pH changes were previously found in connection with some of the compounds tested here, such as FasL, TNF-α, etoposide, cisplatin, or arsenic.1, 2, 22, 23, 24 However, very few studies analysed the role of mitochondrial matrix pH (pHM) during chemically induced apoptosis. Although one work described an early mitochondrial matrix alkanisation,4 it appears that this transient phase is followed by a significant matrix acidification leading to apoptosis.25 In our study, pHi acidification, associated with pHM drop, appears to be essential for specific SQR inhibition and subsequent apoptosis, as pHi modification by EIPA (acidifying compound) or NHE1 overexpression (acidification inhibition) can either potentiate or block cell death, respectively. Moreover, assays both in vitro (Figure 6a) and in intact cells (Figures 3a with 1b and e) for complex II activities underline the specific sensitivity of the SQR function to acidification. These data suggest that complex II is an important sensor for pro-apoptotic signals through its pH sensitivity (schematised in Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Model for the role of specific complex II inhibition for apoptosis induction by various pro-apoptotic compounds. (a) In healthy cells, complex II serves to funnel electrons derived from the Krebs cycle to the respiratory chain. SDHA-mediated oxidation of succinate to fumarate by the succinate dehydrogenase activity (SDH), as part of the Krebs cycle, provides electrons to complex II. They are transferred to the iron-sulfur centres of the SDHB subunit and finally to the CoQ reduction site at the interface between SDHC and SDHD, the two transmembrane subunits of complex II. The succinate CoQ oxidoreductase (SQR) reaction comprises, in addition, the transfer of the electrons to CoQ. (b) Pro-apoptotic compounds, such as various anticancer drugs, FasL, or TNF-α, induce intracellular (pHi) and mitochondrial (pHM) acidification. These pH changes lead to the dissociation of the SDHA/B subunits from complex II and finally to the partial inhibition of the SQR activity without any impairment of the SDH reaction. This specific inhibition leads to complex II uncoupling, superoxide production, and apoptosis

Our experiments with isolated mitochondria in buffers with different pH or recovered from cells treated with drugs indicated that complex II is unstable and can specifically dissociate. Blue native gel electrophoresis of complex II indicated that SDHA and SDHB, the two subunits exposed to the matrix and attached to the complex II-membrane anchors can be released from this complex (Figure 6b). This is in agreement with earlier studies showing that their association can be broken by chaotrophic ions and treatments such as freeze–thawing.26, 27 As the SDH activity is associated with SDHA/B this dissociation retains this enzymatic activity but abrogates the downstream SQR function, leading to the uncoupling between SDH and SQR activity (Figure 7).

ROS generation by respiratory chain complex II

Before apoptosis induction we observed a partial reduction of the total cellular complex II SQR activity (Figure 3a). We believe that this is due to some of the complex II aggregates in the affected cells shutting down the SQR activity while maintaining the SDH activity (Figure 7b). As a result of this specific complex II inhibition, the electron flux from the citrate cycle through complex II is altered in three ways (i) electrons cannot efficiently be transferred to the ubiquinone-binding sites; (ii) the electron flow is disrupted within the complex; and (iii) the electrons react with molecular oxygen to produce superoxide radicals, which eventually trigger apoptosis (Figure 7). Of note, the DHE and MitoSOX probes used in this study have been described as relatively specific for superoxide detection, even though they may give an unspecific response for superoxides,28 notably at the 488 nm excitation wavelength used for FACS application. However, we showed that the superoxide scavenger SOD can potently reduce (i) the DHE and MitoSOX signals induced upon complex II inhibition and (ii) the subsequent apoptosis (Figure 5b–d and Supplementary Figure 3d), confirming that the complex II blockade generates superoxides. A block in various complexes of the respiratory chain has been shown to induce ROS formation and subsequent apoptosis,5 particularly at the complex I and III level.6 Interestingly, the cleavage of complex I subunits NDUFS1 or NDUFS3 by caspases29 or granzyme A,30 respectively, can lead to superoxides and apoptosis. Long considered a physiologically negligible site for ROS production, complex II has been recently described by us16 and others to mediate intracellular signalling through superoxide generation in a number of scenarios, such as (i) mutations of the coenzyme Q (CoQ)-binding site of SDHC in Caenorhabditis elegans,31 Escherichia coli,12 Saccharomyces cerevisiae,32 and mammals;7 (ii) mutation or destabilisation of SDHB;33 and (iii) chemical inhibition of the succinate or CoQ-binding site.34 Different sites for superoxide generation within complex II have been proposed depending on the cause of complex II inhibition, notably at the SDHC/D CoQ-binding site32 or between the SDHA-embedded FAD group and a downstream obstruction.33 Nevertheless, the precise molecular mechanisms of such a blockade were rarely explored. Some recent studies have evoked either a stabilisation of the ubisemiquinone radical35 or a modification of the glutathionylation and the tyrosine nitration status of SDHA.36 Our data demonstrate that another major cellular factor, pHi homoeostasis, can have an impact on complex II functions and facilitate ROS production.

Role of complex II in tumourigenesis

Mutations in the SDHB, C and D subunits that cripple complex II have been found in various cancers, particularly paragangliomas and phaeochromocytomas,17 suggesting that this confers a selective growth advantage to cells and led to define its subunits as tumour suppressor proteins.10 During the past 10 years, research exploring the biochemical causes of complex II inhibition and tumourigenesis found different metabolic pathways to be involved. First, in complex II-impaired cells, the SDH substrate succinate accumulates in the mitochondria, is transported into the cytosol, and inhibits HIF1α prolyl hydroxylase. This leads to HIF1α stabilisation and activation,37 and finally to a pseudohypoxia tumor phenotype38 and apoptosis inhibition.21 A second pathway involves the generation of ROS in association with mutated or destabilised complex II7, 33 leading to mtDNA damage39 and likewise HIF1α activation.33 Our results allow us to propose a third pathway that highlights the role of complex II as a major apoptosis regulator: Numerous pro-apoptotic signals target complex II and lead to (i) a specific inhibition of SQR activity without SDH impairment; (ii) uncoupling of these two enzymatic activities; (iii) superoxide production; and finally (iv) cell death induction. Our shRNA experiments (Figure 3b–e and Supplementary Figure 4) and data from SDHC-negative B9 cells (Figures 3f and 5f) indicate that specific downregulation of complex II subunits inhibits the aggregation of the whole complex II in the mitochondria. This on its own does not elicit apoptosis (HeLa cells, Figure 3d) and even leads to anticancer drug resistance (B9 cells, Figure 3f). These findings are also supported by other independent studies showing that, in cancer patients with mutations in complex II subunits, the remaining components of this complex are either not present40 or display a profoundly reduced complex II activity.41 Hence, in tumours harbouring such altered genes, the combination of a partial SQR inhibition and a fully active SDH is not possible, as both activities are downregulated, therefore impairing the apoptotic process. We believe that this is the reason why these cells can survive the onset of such mutations and eventually form tumour cells. This model does not exclude that parallel processes, such as a hypoxia-like pathway through the stabilisation of the HIF1α transcription factor,37 also contribute to tumorigenesis. Nevertheless, our findings can contribute to explain why components of complex II function as tumour suppressor genes.

In conclusion, our study brings together two common features of apoptosis in response to pro-apoptotic signals: pHi change and ROS formation. We found that they are interconnected by the specific inhibition of complex II of the respiratory chain, which is accomplished by the release of the SDHA/SDHB subunits from the whole complex.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and treatments

Human HeLa cells and the SDHC-deficient B9 cells, derivatives from the Chinese hamster CCL16 parental cell line (B1 cells),19 were cultivated as described.16 The concentrations used for treatments are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Chemicals

All the reagents are described in Supplementary Experimental Procedures.

ShRNA constructs

ShRNA against human SDHA/B/C/D were designed (Supplementary Table 2) and checked for specificity with the iRNAi software (http://www.mekentosj.com/irnai/). Specific primers for SDHA/B/C/D as well as scrambled primers (of the SDHB sequence) as a negative control were synthesised and inserted into pSuper vector (Oligoengine, Seattle, WA, USA).

Transfections and plasmids

Cells were transfected with plasmid DNA either by Lipofectamine 2000 or Effectene in B9 (30% efficiency after 48 h) or HeLa cells (60–70% after 24 h), respectively. For stable transfections, B9 cells were selected at 3 weeks with 800 μg/ml G418. Previously described expression vectors for mitochondrial MnSOD, catalase, luciferase, NHE1, and wt SDHC were used.16, 42, 43

Apoptosis and necrosis quantification

Apoptotic cells were quantified using flow cytometry by determining the percentage of cells with subG1-DNA content. This subG1 population was analysed after cell permeabilisation and subsequent PI staining, as previously described.16, 44 For some experiments, apoptosis and necrosis were quantified at the same time on non-permeabilised cells by flow cytometry with an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated AV and PI kit, according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK). Cells with compromised membrane integrity were also specifically quantified by flow cytometry using 7-AAD, according to the supplier's protocol (Invitrogen).

ROS detection

The ROS-sensitive probe DHE and its mitochondria-targeted derivative MitoSOX were used, according to previously published protocols.33, 45 Briefly, cells were treated with the indicated conditions, harvested, and washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) before the addition of 150 μl of a PBS solution containing DHE (5 μM) or MitoSOX (5 μM). Cells were incubated at 37°C for 25 or 10 min, respectively, and then washed and resuspended in PBS. Fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry using a FACScalibur (FL2-H channel), and a minimum of 4000 cells were counted for each sample.

Total RNA isolation and reverse transcriptase PCR assay

Total RNAs were extracted with TRIzol and subjected to reverse transcriptase PCR.18 The primers used are described in Supplementary Table 3.

Mitochondria isolation

Mitochondria were isolated with established protocols,18 resuspended in lysis buffer, and kept at −80°C.

Complex II activity assays

Complex II activities were measured by spectrophotometric tests on 10 μg of mitochondria, using the SDH (PMS-mediated DCPIP reduction) and the SQR assay (CoQ-dependent reduction of DCPIP).16, 18 For measurements at pH 6.7 and 7.3, we used the normal phosphate buffer with different ratios K2HPO4/KH2PO4 to obtain the acidic or neutral pH (Gomorri Buffers tables).

Western blotting

For each sample, mitochondria (30 μg) were separated in a 14% SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and electroblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes (BioRad, Hemel Hempstead, UK), which were processed as described.18 Goat polyclonal Abs against SDHB and SDHD were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Heidelberg, Germany), mouse mAbs against SDHA and COX IV from Abcam (Cambridge, UK), and mouse mAbs against Cyt c and SDHC from BD Pharmingen (Oxford, UK) and Abnova (Stratech Scientific, Newmarket, UK), respectively.

Measurements of pHi

The pHi of HeLa cells was monitored using the pH-sensitive fluorescent probe carboxy-SNARF-1. After a 7-h treatment, cells were collected and loaded with SNARF (5 μM) for 30 min at 37°C, in a cell suspension buffer (CSB). The mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of 10 000 cells was determined by flow cytometry (λex.=488 nm, λem.=FL2-H 580 nm and FL3-H 640 nm). The emission ratio 640/580 was converted into pH value by using the calibration curve obtained in situ on control cells exposed to calibration buffers containing 10 μM nigericin.43

Mitochondrial matrix pH

The pHM was monitored using two mitochondrial targeted plasmids (Aequotech, Ferrara, Italy): mt-EYFP (pH-sensitive enhanced yellow fluorescent protein) and mt-dsRed (pH-insensitive red fluorescent protein) used as a transfection rate control.46 HeLa cells were co-transfected overnight with these two plasmids. After 24 h, cells were treated for 7 h with the different pro-apoptotic agents. Cells were then collected, re-suspended in CSB, and analysed by flow cytometry. MFI was determined on 10 000 cells (λex.=488 nm, λem. EYFP=FL1-H 530 nm and λem. DsRed=FH3-H 640 nm). A standard curve was generated in situ on control cells exposed to calibration buffers containing ionophores nigericin and monensin, allowing the conversion of the MFI ratio 530/640 into pH value. CCCP, a mitochondrial protonophore, was used as control for pHM acidification.46

Blue native gel PAGE

For in vitro pH experiments, fresh mitochondria isolated using a commercial isolation kit (Pierce, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cramlington, UK) were incubated in the indicated phosphate buffer (see complex II activity assays). Mitochondrial complex II was gently solubilised in a 50 mM Bis–Tris buffer containing 1.25% n-dodecyl--maltoside and 750 mM 6-aminocaproic acid on ice for 30 min and the supernatant collected after centrifugation (20 000 × g, 30 min). For experiments on transfected and/or treated cells, HeLa cells were lysed using 5% n-dodecyl--maltoside in PBS. Samples were incubated on ice for 30 min and centrifuged (17 000 × g, 30 min). For both experiments, Native Sample buffer (Bio-Rad), supplemented with 1.25% (final concentration) Coomassie Brilliant Blue G solution (5% Coomassie Brilliant Blue G, 750 mM 6-aminocaproic acid and 50 mM Bis–Tris), was added to the supernatants. Proteins were loaded on a Ready-Gel 4-15% (Bio-Rad) for Blue Native Page and western blot was performed according to established protocols. Blots were probed with an SDHA antibody (Invitrogen).

Statistical analysis

The results are presented as means±S.D. of at least three independent experiments. Significant differences (P<0.05) were evaluated with the Student t-test. Western blots and PCR results are representative of at least three different experiments.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported with postdoctoral grants by CRUK to AL, by the European commission (Hermione) to LH, by Breast Cancer Campaign to ALMM and by a CRUK PhD stipend to EP. We thank S Irshad, F Osborne, R Iwasawa, R Gence and G Sindelar for helpful advice. We are grateful to Pr L Counillon (CNRS UMR 6548, Nice, France) for the NHE1 plasmid.

Glossary

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SQR

succinate:ubiquinone oxidoreductase

- SDH

succinate dehydrogenase

- NHE1

Na+/H+ exchanger 1

- FasL

Fas ligand

- TNF-α

tumour necrosis factor α

- CoQ

coenzyme Q

- TTFA

thenoyltrifluoroacetate

- 3NP

3-nitroproprionic acid

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- MnSOD

manganese SOD

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Cell Death and Differentiation website (http://www.nature.com/cdd)

Edited by JA Cidlowski

Supplementary Material

References

- Lagadic-Gossmann D, Huc L, Lecureur V. Alterations of intracellular pH homeostasis in apoptosis: origins and roles. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:953–961. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry MA, Reynolds JE, Eastman A. Etoposide-induced apoptosis in human HL-60 cells is associated with intracellular acidification. Cancer Res. 1993;53:2349–2357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Eastman A. Apoptosis in an interleukin-2-dependent cytotoxic T lymphocyte cell line is associated with intracellular acidification. Role of the Na(+)/H(+)-antiport. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:3203–3211. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.7.3203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama S, Llopis J, Deveraux QL, Tsien RY, Reed JC. Changes in intramitochondrial and cytosolic pH: early events that modulate caspase activation during apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:318–325. doi: 10.1038/35014006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci JE, Waterhouse N, Green DR. Mitochondrial functions during cell death, a complex (I-V) dilemma. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:488–492. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott M, Gogvadze V, Orrenius S, Zhivotovsky B. Mitochondria, oxidative stress and cell death. Apoptosis. 2007;12:913–922. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0756-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii T, Yasuda K, Akatsuka A, Hino O, Hartman PS, Ishii N. A mutation in the SDHC gene of complex II increases oxidative stress, resulting in apoptosis and tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:203–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLennan HR, Degli Esposti M. The contribution of mitochondrial respiratory complexes to the production of reactive oxygen species. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2000;32:153–162. doi: 10.1023/a:1005507913372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yankovskaya V, Horsefield R, Tornroth S, Luna-Chavez C, Miyoshi H, Leger C, et al. Architecture of succinate dehydrogenase and reactive oxygen species generation. Science. 2003;299:700–704. doi: 10.1126/science.1079605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb E, Tomlinson IP. Mitochondrial tumour suppressors: a genetic and biochemical update. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:857–866. doi: 10.1038/nrc1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun F, Huo X, Zhai Y, Wang A, Xu J, Su D, et al. Crystal structure of mitochondrial respiratory membrane protein complex II. Cell. 2005;121:1043–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecchini G. Function and structure of complex II of the respiratory chain. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:77–109. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng S, Kruger A, Kleschyov AL, Kalinowski L, Daiber A, Wojnowski L. Gp91phox-containing NAD(P)H oxidase increases superoxide formation by doxorubicin and NADPH. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:466–473. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham NA, Hedley DW. Respiratory chain-generated oxidative stress following treatment of leukemic blasts with DNA-damaging agents. Exp Cell Res. 2001;264:345–352. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckman JS, Minor RL, Jr, White CW, Repine JE, Rosen GM, Freeman BA. Superoxide dismutase and catalase conjugated to polyethylene glycol increases endothelial enzyme activity and oxidant resistance. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:6884–6892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albayrak T, Scherhammer V, Schoenfeld N, Braziulis E, Mund T, Bauer MK, et al. The tumor suppressor cybL, a component of the respiratory chain, mediates apoptosis induction. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:3082–3096. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-10-0631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baysal BE. Clinical and molecular progress in hereditary paraganglioma. J Med Genet. 2008;45:689–694. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.058560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemarie A, Grimm S. Mutations in the heme b-binding residue of SDHC inhibit assembly of respiratory chain complex II in mammalian cells. Mitochondrion. 2009;9:254–260. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oostveen FG, Au HC, Meijer PJ, Scheffler IE. A Chinese hamster mutant cell line with a defect in the integral membrane protein CII-3 of complex II of the mitochondrial electron transport chain. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26104–26108. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.44.26104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConkey DJ. Biochemical determinants of apoptosis and necrosis. Toxicol Lett. 1998;99:157–168. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(98)00155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Nakamura E, Yang H, Wei W, Linggi MS, Sajan MP, et al. Neuronal apoptosis linked to EglN3 prolyl hydroxylase and familial pheochromocytoma genes: developmental culling and cancer. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:155–167. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwama K, Nakajo S, Aiuchi T, Nakaya K. Apoptosis induced by arsenic trioxide in leukemia U937 cells is dependent on activation of p38, inactivation of ERK and the Ca2+-dependent production of superoxide. Int J Cancer. 2001;92:518–526. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson C, Johansson U, Johansson AC, Kagedal K, Ollinger K. Cytosolic acidification and lysosomal alkalinization during TNF-alpha induced apoptosis in U937 cells. Apoptosis. 2006;11:1149–1159. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-7108-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebillard A, Rioux-Leclercq N, Muller C, Bellaud P, Jouan F, Meurette O, et al. Acid sphingomyelinase deficiency protects from cisplatin-induced gastrointestinal damage. Oncogene. 2008;27:6590–6595. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi A, Masuda A, Sun M, Centonze VE, Herman B. Oxidative stress-induced apoptosis is associated with alterations in mitochondrial caspase activity and Bcl-2-dependent alterations in mitochondrial pH (pHm) Brain Res Bull. 2004;62:497–504. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2003.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatefi Y, Galante YM. Isolation of cytochrome b560 from complex II (succinateubiquinone oxidoreductase) and its reconstitution with succinate dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:5530–5537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baginsky ML, Hatefi Y. Reconstitution of succinate-coenzyme Q reductase (complex II) and succinate oxidase activities by a highly purified, reactivated succinate dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 1969;244:5313–5319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson KM, Janes MS, Beckman JS. The selective detection of mitochondrial superoxide by live cell imaging. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:941–947. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricci JE, Munoz-Pinedo C, Fitzgerald P, Bailly-Maitre B, Perkins GA, Yadava N, et al. Disruption of mitochondrial function during apoptosis is mediated by caspase cleavage of the p75 subunit of complex I of the electron transport chain. Cell. 2004;117:773–786. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinvalet D, Dykxhoorn DM, Ferrini R, Lieberman J. Granzyme A cleaves a mitochondrial complex I protein to initiate caspase-independent cell death. Cell. 2008;133:681–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii N, Fujii M, Hartman PS, Tsuda M, Yasuda K, Senoo-Matsuda N, et al. A mutation in succinate dehydrogenase cytochrome b causes oxidative stress and ageing in nematodes. Nature. 1998;394:694–697. doi: 10.1038/29331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szeto SS, Reinke SN, Sykes BD, Lemire BD. Ubiquinone-binding site mutations in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae succinate dehydrogenase generate superoxide and lead to the accumulation of succinate. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27518–27526. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700601200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzy RD, Sharma B, Bell E, Chandel NS, Schumacker PT. Loss of the SdhB, but Not the SdhA, subunit of complex II triggers reactive oxygen species-dependent hypoxia-inducible factor activation and tumorigenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:718–731. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01338-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liot G, Bossy B, Lubitz S, Kushnareva Y, Sejbuk N, Bossy-Wetzel E. Complex II inhibition by 3-NP causes mitochondrial fragmentation and neuronal cell death via an NMDA- and ROS-dependent pathway. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:899–909. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran QM, Rothery RA, Maklashina E, Cecchini G, Weiner JH. The quinone binding site in Escherichia coli succinate dehydrogenase is required for electron transfer to the heme b. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32310–32317. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607476200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CL, Chen J, Rawale S, Varadharaj S, Kaumaya PP, Zweier JL, et al. Protein tyrosine nitration of the flavin subunit is associated with oxidative modification of mitochondrial complex II in the post-ischemic myocardium. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:27991–28003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802691200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selak MA, Armour SM, MacKenzie ED, Boulahbel H, Watson DG, Mansfield KD, et al. Succinate links TCA cycle dysfunction to oncogenesis by inhibiting HIF-alpha prolyl hydroxylase. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:77–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervera AM, Apostolova N, Crespo FL, Mata M, McCreath KJ. Cells silenced for SDHB expression display characteristic features of the tumor phenotype. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4058–4067. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EH, Janknecht R, Maher LJ., III Succinate inhibition of alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent enzymes in a yeast model of paraganglioma. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:3136–3148. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douwes Dekker PB, Hogendoorn PC, Kuipers-Dijkshoorn N, Prins FA, van Duinen SG, Taschner PE, et al. SDHD mutations in head and neck paragangliomas result in destabilization of complex II in the mitochondrial respiratory chain with loss of enzymatic activity and abnormal mitochondrial morphology. J Pathol. 2003;201:480–486. doi: 10.1002/path.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez-Roqueplo AP, Favier J, Rustin P, Rieubland C, Kerlan V, Plouin PF, et al. Functional consequences of a SDHB gene mutation in an apparently sporadic pheochromocytoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:4771–4774. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfeld N, Bauer MK, Grimm S. The metastasis suppressor gene C33/CD82/KAI1 induces apoptosis through reactive oxygen intermediates. FASEB J. 2004;18:158–160. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0420fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekpli X, Huc L, Lacroix J, Rissel M, Poet M, Noel J, et al. Regulation of Na+/H+ exchanger 1 allosteric balance by its localization in cholesterol- and caveolin-rich membrane microdomains. J Cell Physiol. 2008;216:207–220. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccardi C, Nicoletti I. Analysis of apoptosis by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:1458–1461. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemarie A, Bourdonnay E, Morzadec C, Fardel O, Vernhet L. Inorganic arsenic activates reduced NADPH oxidase in human primary macrophages through a Rho kinase/p38 kinase pathway. J Immunol. 2008;180:6010–6017. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.9.6010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinton P, Rimessi A, Romagnoli A, Prandini A, Rizzuto R. Biosensors for the detection of calcium and pH. Methods Cell Biol. 2007;80:297–325. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(06)80015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.