Abstract

FRET analysis has been used to examine the folded conformations and differing kinetic stabilities of two DNA G-quadruplexes (c-kit 1 and c-kit 2) derived from sequences found in the promoter of the c-kit proto-oncogene.

G-rich DNA strands can form secondary structures known as G-quadruplexes through the association of at least two hydrogen bonded G-tetrads, consisting of four guanines that are held together via Hoogsteen H-bonding.1 The potential formation of G-quadruplexes in vivo is of significant fundamental interest particularly with regard to the possibility that such structures may be functional.1 G-quadruplex forming sequences are prevalent throughout the human genome2 and are enriched in the promoter regions of protein coding genes.3 A number of studies have been carried out on promoter quadruplexes associated with proto-oncogenes, that have included c-myc,4 c-kit,5,6 VEGF7 and bcl-2.8 Recently it has been shown that negative superhelicity plays a role in the formation of the c-myc promoter quadruplex,9 suggesting that these quadruplexes may ‘store’ superhelicity and could be associated with DNA melting at the transcription start point.9

The proto-oncogene c-kit encodes a tyrosine kinase receptor that plays a role in the control of cellular differentiation.10 The c-kit promoter has two non-overlapping quadruplex motifs.5,6 A 22 base G-rich sequence between −87 and −109 base pairs upstream from the transcription start site of the human c-kit gene, d(5′-AGGGAGGGCGCTGGGAGGAGGG-3′), has been shown to fold into a quadruplex (c-kit 1).5 The high resolution NMR structure of the quadruplex formed from this sequence shows an unusual structure with G-10 (in bold above) forming part of the top tetrad (core tetrad forming G in italics).5b A second G-rich sequence, d(5′-CGGGCGGGCGCGAGGGAGGGG-3′), situated −140 to −160 base pairs upstream from the transcription start site has also been shown by 1H-NMR spectroscopy to form an all parallel quadruplex (c-kit 2).6,11 CD and UV spectroscopy have also been used to show that both sequences form stable quadruplex structures under near physiological conditions.5,6 Recently it has been shown that treatment of cells with c-kit 2 specific quadruplex ligands can reduce the in vitro expression levels of c-kit.12,13 Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) has been used to study the structural heterogeneity and dynamics of several quadruplexes that have included the human telomeric quadruplex (H-telo)14 and the c-kit 2 quadruplex in its natural duplex context.15 The unfolding dynamics of promoter quadruplexes is of fundamental interest and may reflect on their biological roles. Also the kinetic stability of the quadruplexes may play a role in their potential as targets for therapeutics. Herein we report single molecule FRET studies and on the opening kinetics of the c-kit 1 and c-kit 2 quadruplexes.

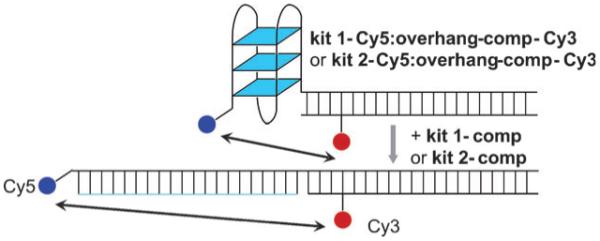

The system design (Fig. 1) comprises a quadruplex forming sequence (c-kit 1 or c-kit 2), flanked by an acceptor fluorophore (Cy5) at the 5′-end, and a 35 base 3′-overhang (oligonucleotides kit 1-Cy5 and kit 2-Cy5 respectively, see ESI†). The oligonucleotide complementary to the 35 base overhang contained an internal donor fluorophore (Cy3) at T-28 (overhang-comp-Cy3). The positioning of the Cy3 fluorophore on the complementary strand allows separation of the fluorophore from the quadruplex, preventing interactions which may cause quenching. The overall system design is based on that used by Ying et al.14 The unlabelled versions of all oligonucleotides were employed as controls (kit 1, kit 2 and overhang-comp). Upon quadruplex formation the distance between the donor and acceptor fluorophores decreases leading to an increase in FRET (Fig. 1). Hybridization of an oligonucleotide complementary to the quadruplex forming region causes a concomitant separation of the two dyes and a large decrease in FRET, enabling the unfolding kinetics to be monitored. The quadruplex systems (kit 1, kit 2, kit 1:overhang-comp and kit 2:overhang-comp) were characterized by UV thermal melting and circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy. UV melting temperatures for the single strands (kit 1 and kit 2) recorded at 295 nm in the presence of 100 mM K+ were in agreement with the literature (see ESI†).5a,6

Fig. 1.

Schematic for the unfolding of c-kit 1 and c-kit 2 quadruplexes.

The thermal melting profile of kit 1-Cy5:overhang-comp-Cy3 shows an increased quadruplex melting temperature of 57 ± °C, compared to the unlabelled system (Tm = 50 ± 3 °C)16 This increase in melting temperature is comparable to that reported for a similar system with H-telo.14 The CD spectra for both quadruplex systems (kit 1-Cy5:overhang-comp-Cy3 and kit 2-Cy5:overhang-comp-Cy3), in 100 mM K+, show a large positive signal at 260 nm and a negative signal at 240 nm which is consistent with a predominantly parallel quadruplex structure (ESI†).5a,6

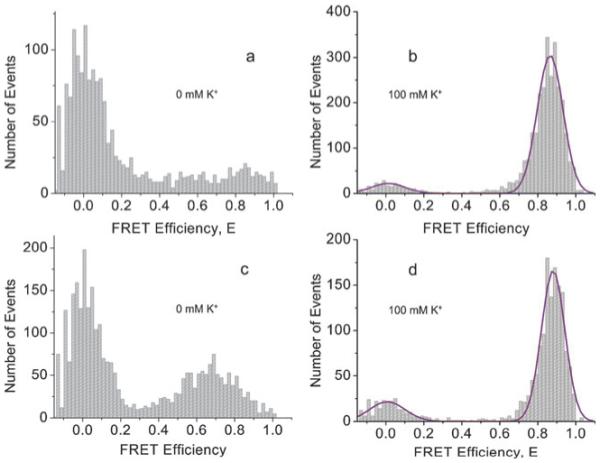

Single molecule FRET analysis of freely diffusing kit 1-Cy5:overhang-comp-Cy3 and kit 2-Cy5:overhang-comp-Cy3 in the presence of 100 mM K+ at 20 °C revealed only one high FRET species, E ~ 0.90, (Fig. 2b and d). Upon increasing the temperature to 37 °C the same high FRET species was observed, for both systems (ESI†). In the absence of added K+ the high FRET population was decreased significantly, suggesting a strong potassium dependence on folding, as would be expected for quadruplex structures (Fig. 2a and c). In the presence of 100 mM Na+ at 37 °C a greater proportion of medium and high FRET species were observed, as compared to in the absence of added salt (ESI†). This suggests a number of different quadruplexes or partially folded quadruplexes may exist in the presence of 100 mM Na+. The single high FRET population observed for c-kit 1 in the presence of 100 mM K+ (Fig. 2b) is consistent with the single species observed by NMR spectroscopy.5 For c-kit 2 only one conformation was detectable by single molecule FRET.

Fig. 2.

Single molecule histograms of FRET efficiencies for c-kit 1 and c-kit 2 quadruplexes (a) in 0 mM K+ for c-kit 1; (b) in 100 mM K+ for c-kit 1 with a Gaussian fit; (c) in 0 mM K+ for c-kit 2; (d) in 100 mM K+ for c-kit 2 with a Gaussian fit. All are in 10 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.4) at 20 °C.

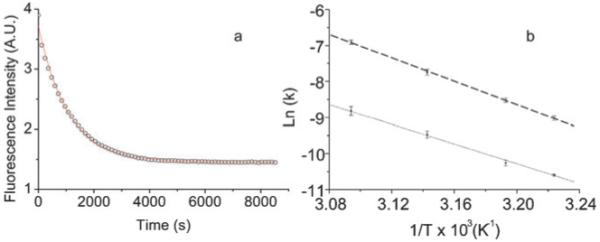

Hybridization of excess kit 1-comp or kit 2-comp (10-fold) to either kit 1-Cy5:overhang-comp-Cy3 or kit 2-Cy5:overhang-comp-Cy3, respectively, interrogates the unfolding of the quadruplex by trapping the duplex. The concomitant decrease in FRET enables the unfolding kinetics to be monitored. The rate of unfolding was measured in the presence of 100 mM K+ at 37, 40, 45 and 50 °C by ensemble fluorescence measurements (Table 1).17 Fig. 3a shows an example of the data recorded, fitted with a single exponential decay as a best fit. The time constants, τ, for the opening of c-kit 1 and c-kit 2 were obtained from these fits. The good fit of the data to a single exponential is consistent with a single quadruplex species being unfolded, although we cannot rule out multiple species, each being unfolded at the same rate.

Table 1.

Rate of unfolding of c-kit 1 and c-kit 2 quadruplexes at 1 μM concentration of the complementary strand

| c-kit 1 |

c-kit 2 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T/°C | τ/s | k × 10−5/s−1 | τ/s | k × 10−5/s−1 |

| 37 | 8200 ± 400 | 12 ± 1 | 40100 ± 1500 | 2.5 ± 0.1 |

| 40 | 5100 ± 220 | 20 ± 1 | 28980 ± 1600 | 3.5 ± 0.2 |

| 45 | 2300 ± 170 | 43 ± 3 | 13520 ± 1000 | 7.4 ± 1 |

| 50 | 1000 ± 60 | 100 ± 6 | 6815 ± 740 | 15 ± 2 |

Fig. 3.

(a) The decrease of Cy5 fluorescence monitored at 660 nm as the quadruplex formed by kit 1-Cy5:overhang-comp-Cy3 is opened then trapped by kit 1-comp at 50 °C. The data is shown as open circles and fit to a single exponential as a solid line. (b) Arrhenius plot of rate with varying temperature with linear fit of the data for both c-kit 1 (thick dashed line) and c-kit 2 (thin dashed line).

For c-kit 1 and c-kit 2, the rate of quadruplex opening, k, was found to be independent of the concentration of the complementary strand suggesting that quadruplex unfolding is first order and rate determining, while hybridization of the complementary strand to form the duplex is relatively fast. It is likely that there is a partial unfolding of the quadruplex, giving a suffciently disturbed structure which allows a fast hybridization of the complementary strand. The c-kit 1 quadruplex unfolds faster than c-kit 2, with the rate being 4-fold faster at 37 °C and almost 7-fold faster at 50 °C.

Arrhenius analysis of the data was used to obtain the activation energy (Ea) for the unfolding of the quadruplexes (Fig. 3b and Table 2). As the hybridization of the complementary strand is fast under the conditions studied the values obtained relate to the formation of the highest energy intermediate along the unfolding pathway. The activation energy for c-kit 1 is greater than for c-kit 2 (135 ± 5 kJ mol−1 and 113 ± 6 kJ mol−1 respectively) thus the rate of unfolding of c-kit 1 shows greater temperature dependence than that of c-kit 2, over the range of temperatures measured.

Table 2.

Parameters derived from the Arrhenius plots for c-kit 1 and c-kit 2 unfolding at 37 °C

| Ea/kJ mol−1 | Δ‡H/kJ mol−1 | Δ‡S/J K−1 mol−1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| c-kit 1 | 135 ± 5 | 133 ± 5 | 107 ± 16 |

| c-kit 2 | 113 ± 6 | 111 ± 6 | 25 ± 20 |

The changes in enthalpy and entropy going to the transition state (Δ‡H and Δ‡S respectively) were calculated using an Eyring plot (ln(k/T) vs. 1/T). The linear fit of the data gives Δ‡H from the gradient (m) and Δ‡S from the intercept (c) using eqn (1) and (2), respectively.

| (1) |

| (2) |

The Δ‡H calculated for both systems is large and positive while the calculated Δ‡S is small and positive. c-kit 1 has a larger Δ‡H than c-kit 2 (133 ± 5 kJ mol−1 and 111 ± 6 kJ mol−1 respectively, Table 2) and also has a larger Δ‡S than c-kit 2 (107 ± 16 J K−1 mol−1 and 25 ± 20 J K−1 mol−1 respectively). The large positive Δ‡H will dominate the free energy of unfolding, as the contribution of the Δ‡S at 37 °C is small by comparison (TΔ‡S for c-kit 1 is 33 ± 5 kJ mol−1 while for c-kit 2 it is 8 ± 6 kJ mol−1 at 37 °C). The unfolding of both quadruplexes is thus enthalpy driven. The positive Δ‡S for both quadruplexes is consistent with unfolding being a unimolecular process depending only on the quadruplex itself (i.e. is independent of the concentration of complementary strand). As c-kit 1 has a larger Δ‡S than c-kit 2, the entropy contribution to the free energy of unfolding will be more for c-kit 1 as compared to c-kit 2. The change in entropy calculated is for the change from the folded quadruplex state to a higher energy transition state from which fast hybridization of the complementary strand can occur. The larger Δ‡S for c-kit 1 as compared to c-kit 2 shows a greater conformational unfolding is required to reach the high energy transition state, presumably a partially unfolded quadruplex. This may be due to the unusual highly structured folded nature of c-kit 1 as shown by NMR spectroscopy.5b In the NMR structure the implication of G-10 in tetrad formation along with a number of interactions between bases in the loops leads to a highly structured quadruplex.

The intramolecular Oxytricha telomeric quadruplex, d[(TTTTGGGG)4], has been shown to have a half life of 6.5 × 104 s in 50 mM K+ at 37 °C,18 compared with 5.7 × 103 s for c-kit 1 and 2.8 × 104 s for c-kit 2 in 100 mM K+ at 37 °C. Using previously published data for the FRET opening of H-telo quadruplex with a PNA complement in 100 mM K+ at 37 °C, the half life can be calculated as 1.0 × 104 s.19 These half lives are of a similar order of magnitude to those calculated for c-kit 1 and c-kit 2.

The opening rates of two quadruplexes (c-kit 1 and c-kit 2) have been examined by FRET based kinetics and they show different kinetic stabilities. c-kit 1 unfolds faster than c-kit 2 in 100 mM KCl, with the unfolding rate being four times faster at 37 °C. Both quadruplexes have small positive entropies and large positive enthalpies, as such the unfolding is enthalpically driven. It has been suggested that such quadruplexes may form at times when duplex DNA is melted, e.g. during replication or transcription. The unfolding rates of the quadruplexes suggest that they may have suffcient lifetime for small molecules to interact with them, consistent with the cellular effects of small molecules that have been reported.12,13 Thus the intrinsic biophysical properties of the c-kit promoter quadruplexes suggest they may be interesting biological targets for small molecule intervention.

Acknowledgments

We thank the BBSRC for funding (grant No. BB/C51444X/1 and JF206072) and Almac Sciences for contributing towards a studentship for AF.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available: Oligonucleotide sequences, UV melting temperature, CD spectra and single molecule data.

Notes and references

- 1.Neidle S, Balasubramanian S, editors. Quadruplex Nucleic Acids. RSC Publishing; Cambridge: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Todd AK, Johnston M, Neidle S. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:2901. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Huppert JL, Balasubramanian S. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:2908. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huppert JL, Balasubramanian S. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:406. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siddiqui-Jain A, Grand CL, Bearss DJ, Hurley LH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:11593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182256799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Rankin S, Reszka AP, Huppert J, Zloh M, Parkinson GN, Todd AK, Ladame S, Balasubramanian S, Neidle S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:10584. doi: 10.1021/ja050823u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Burge S, Parkinson GN, Hazel P, Todd AK, Neidle S. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:5402. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernando H, Reszka AP, Huppert J, Ladame S, Rankin S, Venkitaraman AR, Neidle S, Balasubramanian S. Biochemistry. 2006;45:7854. doi: 10.1021/bi0601510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun D, Guo K, Rusche JJ, Hurley LH. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:6070. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dexheimer TS, Sun D, Hurley LH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:5404. doi: 10.1021/ja0563861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun D, Hurley LH. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:2863. doi: 10.1021/jm900055s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yarden Y, Kuang WJ, Yang-Feng T, Coussens L, Munemitsu S, Dull TJ, Chen E, Schlessinger J, Francke U, Ullrich A. EMBO J. 1987;6:3341. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02655.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsu SD, Varnai P, Bugaut A, Reszka AP, Neidle S, Balasubramanian S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:13399. doi: 10.1021/ja904007p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bejugam M, Sewitz S, Shirude PS, Rodriguez R, Shahid R, Balasubramanian S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12926. doi: 10.1021/ja075881p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gunaratnam M, Swank S, Haider SM, Galesa K, Reszka AP, Beltran M, Cuenca F, Fletcher JA, Neidle S. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:3774. doi: 10.1021/jm900424a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ying LM, Green JJ, Li HT, Klenerman D, Balasubramanian S. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:14629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2433350100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shirude PS, Okumus B, Ying L, Ha T, Balasubramanian S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:7484. doi: 10.1021/ja070497d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.No melting temperature could be determined for c-kit 2 in the presence of the duplex due to overlapping melting transitions given the expected melting temperatures of 70 °C for the quadruplex and 78 °C for the duplex.

- 17.It was not possible to measure the opening in 100 mM Na+ due to fast kinetics even at low temperatures (τ < 100 s).

- 18.Raghuraman MK, Cech TR. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:4543. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.15.4543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green JJ, Ying LM, Klenerman D, Balasubramanian S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:3763. doi: 10.1021/ja029149w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]