Abstract

High nicotine dependence is a reliable predictor of difficulty quitting smoking and remaining smoke-free. Evidence also suggests that the effectiveness of various smoking cessation treatments may vary by nicotine dependence level. Nicotine dependence, as assessed by Heaviness of Smoking Index baseline total scores, was evaluated as a potential moderator of a message-framing intervention provided through the New York State Smokers’ Quitline (free telephone based service). Smokers were exposed to either gain-framed (n = 810) or standard-care (n = 1222) counseling and printed materials. Those smoking 10 or more cigarettes per day and medically eligible were also offered a free 2-week supply of nicotine patches, gum, or lozenge. Smokers were contacted for follow-up interviews at 3-months by an independent survey group. There was no interaction of nicotine dependence scores and message condition on the likelihood of achieving 7-day point prevalence smoking abstinence at the 3-month follow-up contact. Among continuing smokers at the 3-month follow-up, smokers who reported higher nicotine dependence scores were more likely to report smoking more cigarettes per day and this effect was greater in response to standard-care messages than gain-framed messages. Smokers with higher dependence scores who received standard-care messages also were less likely to report use of nicotine medications compared with less dependent smokers, while there was no difference in those who received gain-framed messages. These findings lend support to prior research demonstrating nicotine dependence heterogeneity in response to message framing interventions and suggest that gain-framed messages may result in less variable smoking outcomes than standard-care messages.

Keywords: Nicotine dependence, smoking cessation, tobacco, message framing, quitline

1. Introduction

There is growing interest in optimally tailoring smoking cessation treatments to smokers’ characteristics (Batra et al., 2010; Haug et al., 2010; Schnoll and Patterson, 2009; Strecher et al., 2006). Studies have reported that the effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions may vary by several smoker characteristics including nicotine metabolic rate (Schnoll et al., 2009a), depression history (Haas et al., 2004), gender (Schnoll and Patterson, 2009), employment status, quit intentions (Haug et al., 2010), alcohol use, history of tobacco-related illness, household makeup (Strecher et al., 2006), and social support (Turner et al., 2008).

Nicotine dependence is an independent risk factor for smoking cessation failure (Baker et al., 2007; Killen and Fortmann, 1994) and may also moderate the impact of different smoking cessation treatments. For example, higher dose nicotine gum was found to increase quit rates among high dependent smokers but not among low dependent smokers (Herrera et al., 1995). Likewise, high dependent smokers may respond differentially to counseling interventions emphasizing either the benefits of quitting smoking (i.e., gain-framed) or the losses of continued smoking (i.e., loss-framed). In a smoking cessation trial of message framing to augment sustained-release (SR) bupropion therapy, high and low dependent smokers had similar smoking abstinence rates in response to gain-framed messages but high dependent smokers were less likely to be abstinent in response to loss-framed messages than low dependent smokers (Fucito et al., 2010). A study of non-treatment seeking smokers, however, demonstrated that loss-framed messages were more persuasive for increasing quit intentions and positive smoking cessation attitudes among high dependent smokers whereas gain-framed messages were more persuasive for low dependent smokers (Moorman and van den Putte, 2008).

In this study, we examined nicotine dependence as a potential moderator of the effects of a message-framing intervention among smokers seeking cessation assistance through a state quitline. Stemming from previous research (Fucito et al., 2010), we hypothesized that high dependent smokers exposed to standard-care messages and printed materials (i.e., mostly non-framed content with minimal discussion of either quitting benefits or smoking costs) would be less likely to achieve short-term smoking abstinence, more likely to report smoking more cigarettes, and less likely to adhere to NRT medication after attempting to quit than low dependent smokers who received standard-care messages. We also anticipated that gain-framed messages (i.e., content emphasizing quitting benefits) would be equally persuasive for promoting smoking cessation among high and low dependent smokers.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

This is a secondary analysis of data from a randomized controlled study of telephone specialists (n = 28) and their smoking clients (n = 2032) who contacted the New York State Smokers’ Quitline (NYSSQL) for smoking cessation assistance from March 10, 2008, through June 13, 2008 (Toll et al., 2010). The study compared smoking cessation outcomes between clients assigned to receive either gain-framed (n = 810) or standard-care (n = 1222) counseling and printed materials. All medically eligible clients in both conditions were also offered NRT (i.e., patch, gum, or lozenge). Eligibility requirements included being: (1) a New York State resident ≥18 years of age, (2) an English speaker, (3) a current smoker seeking quitting assistance, (4) not enrolled in the NYSSQL extended callback program, and (5) not enrolled in any other smoking cessation programs. The 2032 clients (56.8% female, 43.2% male) were primarily Caucasian (79.2%), had a mean age of 46.70 ± 13.73 years, smoked an average of 20.13 ± 11.05 cigarettes per day for a mean of 25.99 ± 14.26 years, and had a mean Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI) score of 3.21 ± 1.56; range = 0-6) (Heatherton et al., 1989).

2.2. Procedure

All clients received an initial intake telephone call that included medical screening for a 2-week starter pack of NRT. Based on the random assignment of their telephone specialist, they then received a web-based structured interview and either: (1) gain-framed or (2) standard-care counseling. Fidelity of counseling delivery was tested and revealed a high level of interrater reliability (mean intraclass coefficients ranged from .87-.99). All callers were mailed NYSSQL smoking cessation printed materials consistent with their experimental condition. Clients then received a 2-week follow-up telephone call and counseling by an NYSSQL specialist consistent with their experimental condition and a 3-month follow-up telephone interview by an independent survey group blind to message condition. The Institutional Review Boards of the Roswell Park Cancer Institute and the Yale University School of Medicine approved this study. More detail about study procedures is available in the original paper (Toll et al., 2010).

2.3. Measures

Heaviness of Smoking Index (HSI) (Heatherton et al., 1989)

This standardized measure of nicotine dependence includes 2 items from the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire - time to the first cigarette of the day and number of cigarettes smoked per day. It yields scores between 0 and 6 and is a reliable predictor of smoking cessation outcomes (Kozlowski et al., 1994). Total centered HSI scores were evaluated in analyses.

Smoking-related outcomes included

(1) point prevalence abstinence over the last 7 days at 3-month follow-up, (2) number of cigarettes smoked per day at 3-month follow-up, and (3) medication adherence at 3-month follow-up (i.e., number of patches, gum pieces, or lozenges used). At the 3-month follow-up, smoking abstinence during the specified period after quitting was defined as self-reported abstinence (i.e., no smoking, not even a puff in the last 7 days). Abstinence was coded categorically (0 = abstinent, 1 = smoking). Clients who dropped out were coded as smoking.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

A t-test evaluated baseline differences in nicotine dependence between message conditions. Logistic regression analyses examined the effects of message condition and nicotine dependence centered scores on 7-day point prevalence abstinence at 3-months. Linear regression analyses evaluated the effects of message condition and nicotine dependence centered scores on: (1) number of cigarettes smoked per day at 3-months and (2) NRT use at 3-months. Regression models were fitted in steps. In Step 1, message condition and nicotine dependence centered scores were entered. In Step 2, the 2-way interaction of message condition and nicotine dependence centered scores was entered. Simple slope analyses were conducted for post-hoc probing of significant interactions (Holmbeck, 2002).

Three-month follow-up data were obtained for 63.3% of the sample (n = 1286) (Toll et al., 2010). The attrition rate was equivalent between conditions. The potential moderating effect of nicotine dependence on smoking abstinence was conducted as an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis (n = 2032) with enrolled participants who dropped out considered to be smoking. This conservative approach is in accordance with the smoking field standard and other large-scale smoking cessation studies (Gonzales et al., 2006; Ahluwalia et al., 2002; Hurt et al., 1997). Analyses of other smoking-related outcomes were conducted using all available follow-up data at 3-months (n = 1286); ITT analyses were more difficult to conduct given the challenge of imputing values for several variables. We chose not to impute baseline smoking values for missing values at 3 months due to criticisms of this approach (Little, 1992); there was no baseline value to impute for NRT adherence.

3. Results

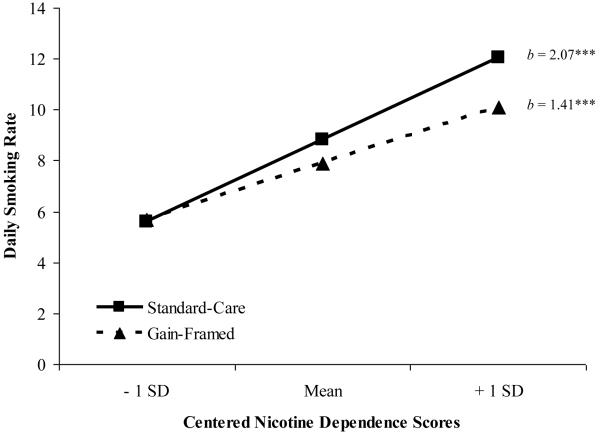

Analyses confirmed conditions were equivalent at baseline on nicotine dependence. There was no significant interaction of nicotine dependence scores and message condition on the likelihood of achieving 7-day point prevalence smoking abstinence at the 3-month follow-up [Wald = .02, p = .90, OR = 1.10]. Among continuing smokers at 3-months, there was a significant interaction of nicotine dependence scores and message condition on number of cigarettes smoked per day [R2 =.10; F (3, 1233) = 45.96, p < .001]. The simple slope of nicotine dependence scores was significant for standard-care messages [b = 2.07; t = 10.01, p < .001] and gain-framed messages [b = 1.41; t = 5.82, p < .001]. The direction and magnitude of both slopes suggested that daily cigarette intake at 3-months was greater among smokers with higher nicotine dependence scores and that this effect was larger in the standard-care condition than the gain-framed condition (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Regression Lines for Association between Daily Smoking Rate at 3-Month Follow-up and Message Condition as a Function of Centered Nicotine Dependence Scores

Note. *** < .001, b = unstandardized regression coefficient

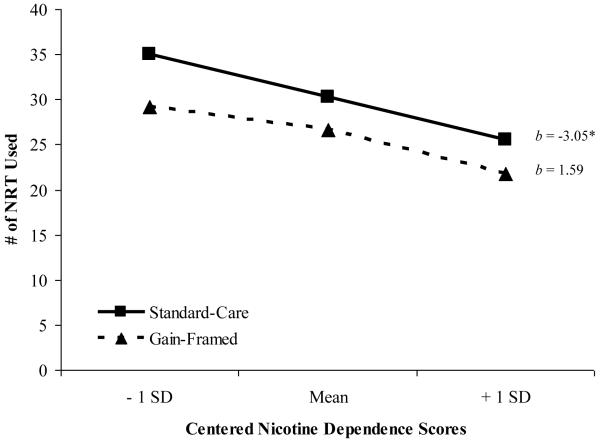

There was also a significant interaction of nicotine dependence scores and message condition on NRT use at 3-months [R2 =.01, F (3, 1199) = 25.52, p = .05]. The simple slope of nicotine dependence scores was significant for standard-care messages [b =−3.05; t = −2.29, p = .02] but not gain-framed messages [b = 1.59; t = 1.00, p = .32]. The direction of the slope for the standard-care condition suggested that NRT use was lower among smokers with higher levels of nicotine dependence (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Regression Lines for Association between Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT) Use at 3-Month Follow-up and Message Condition as a Function of Centered Nicotine Dependence Scores

Note. * < .05, b = unstandardized regression coefficient

To further probe potential mechanisms that may have contributed to different smoking cessation outcomes in the standard-care condition, correlations were conducted between nicotine dependence scores and baseline quitting attitudes (i.e., quitting confidence and importance on 10-point scales). Nicotine dependence scores were modestly, negatively correlated with confidence [r = −.08, p < .001] and unrelated to quitting importance scores.

Specialist was also tested as a factor in the regression models and yielded no significant results [p’s > .10].

4. Discussion

Among smokers who received standard-care messages, those who reported higher baseline nicotine dependence scores reported smoking more cigarettes per day and less frequent NRT use at 3-months follow-up than smokers who reported lower nicotine dependence scores. Contrary to our hypothesis, this interaction was not observed for 7-day point prevalence smoking abstinence rates at 3-months. As anticipated, smoking abstinence rates and NRT use did not vary by nicotine dependence scores among smokers exposed to gain-framed smoking messages; however more dependent smokers also reported smoking more cigarettes per day in this condition than less dependent smokers.

Higher nicotine dependence is associated with greater difficulty quitting smoking so it would be expected that high dependent smokers would have reported lower adherence and greater smoking than low dependent smokers (Baker et al., 2007; Killen and Fortmann, 1994; Kozlowski et al., 1994). However, there was less variability in medication adherence and smoking rates between high and low dependent smokers in the gain-framed condition. These results partially replicate previous research in which high dependent smokers were less likely to be abstinent than low dependent smokers in a loss-framed condition but were equally likely to be abstinent as low dependent smokers in a gain-framed condition (Fucito et al., 2010). Taken together, these findings suggest that delivering gain-framed messages may result in less variable smoking cessation outcomes than loss-framed or standard-care messages.

Potential differences in smoking cessation outcomes between high and low dependent smokers in response to gain-framed messages may have been reduced for several reasons. Greater nicotine dependence is a risk factor for smoking-related illnesses, health concerns are among the key motives for quitting smoking, and high dependent smokers have likely experienced smoking consequences (Deheinzelin et al., 2005; Duncan et al., 1992; Jimenez-Ruiz et al., 2001). Thus, high dependent smokers may have perceived smoking cessation as less risky (i.e., a more certain outcome) and effective for health improvement.

High dependent smokers may have also construed gain-framed messages as less threatening than standard-care messages. Nicotine dependence was negatively correlated with quitting confidence suggesting a slight tendency for more dependent smokers to report lower confidence to quit. Presenting loss-framed messages, believed to convey a greater sense of threat than gain-framed messages, to individuals who perceive themselves less capable of avoiding the threat may result in message avoidance or rejection (Van ’t Riet et al., 2008; Witte, 1992). Thus, presenting smoking messages in gain-framed terms to high dependent smokers may have facilitated message acceptance.

Several study limitations should be noted. Moderator effects were modest. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons of multiple outcomes because this was an exploratory secondary analysis. The assessment of smoking abstinence was limited to 7-day point prevalence abstinence at 3-months. Future studies may wish to incorporate more robust smoking cessation measures such as continuous abstinence over a number of months. Analyses of secondary smoking-related outcomes were limited to the subsample of participants who completed the 3-month follow-up. Although the follow-up rate is consistent with that of other large-scale quitline studies (An et al., 2006; Hollis et al., 2007), the generalizability of results for cigarette intake and NRT adherence is restricted to this subset of quitline participants. Finally, specialist enthusiasm for the gain-framed condition relative to standard-care may have also influenced results, though standardized training and supervision methods and high specialist adherence reduce this concern. In future research, it would be valuable to include a measure of specialist enthusiasm for the intervention in order to address whether there are condition differences, and if so, whether they affect study outcomes.

Quitlines have several advantages including cost-effective smoking cessation treatment that is accessible to all smokers. This study provides preliminary evidence that smokers’ nicotine dependence level may moderate quitline intervention effectiveness, and it is possible that tailored interventions to high dependent callers could enhance smoking-related outcomes. More research is needed to examine the feasibility and effectiveness of such tailoring in the context of a tobacco quitline.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahluwalia JS, Harris KJ, Catley D, Okuyemi KS, Mayo MS. Sustained release bupropion for smoking cessation in African Americans: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:468–474. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An L, Schillo B, Kavanaugh A, Lachter RB, Luxenberg MG, Wendling AH, Joseph AM. Increased reach and effectiveness of a statewide tobacco quitline after the addition of access to free nicotine replacement therapy. Tob Control. 2006;15:286–293. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, Bolt DM, Colby S, Conti D, Giovino G, Hatsukami D, Hyland A, Krishnan-Sarin S, Niaura R, Perkins KA, Toll BA. Time to first cigarette in the morning smoking as an index of ability to quit smoking: implications for nicotine dependence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:S555–S570. doi: 10.1080/14622200701673480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batra A, Collins SE, Schröter M, Eck S, Torchalla I, Buchkremer G. A cluster-randomized effectiveness trial of smoking cessation modified for at-risk smoker subgroups. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;38:128–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns DM, Warner KE. Smokers who have not quit: is cessation more difficult and should we change our strategies? In: Burns DM, editor. Those who Continue to Smoke: Is Abstinence Harder and do we Need to Change our Interventions? Smoking and Tobacco Control. Bethesda, MD: 2003. pp. 11–31. Monograph No. 15. NIH Publication No. 03-5370. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control Tobacco use among adults—United States 2005. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:1145–1148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control Cigarette smoking among adults and trends in smoking cessation—United States, 2008. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:1227–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins SE, Herbert KK, Anderson CM, Mills JA, Zhu S-H. Reaching young adult smokers through quitlines. Am J Public Health. 2007a;97:1402–1405. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.101741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins SE, Bailey L, Campbell S, Koon-Kirby C, Zhu S-H. Tobacco cessation quitlines in North America: a descriptive study. Tob Control. 2007b;16:i9–i15. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.020370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deheinzelin D, Lourenço MTC, da Costa CL, Younes RN. The level of nicotine dependence is an independent risk factor for cancer: A case control study. Clinics. 2005;60:221–226. doi: 10.1590/s1807-59322005000300007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkstra A, Conijn B, De Vries H. A match–mismatch test of a stage model of behaviour change in tobacco smoking. Addict. 2006;101:1035–1043. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan CL, Cummings SR, Hudes ES, Zahnd E, Coates TJ. Quitting smoking: reasons for quitting and predictors of cessation among medical patients. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7:398–404. doi: 10.1007/BF02599155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fucito LM, Latimer AE, Salovey P, Toll BA. Nicotine dependence as a moderator of message framing effects on smoking cessation outcomes. Ann Behav Med. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9187-3. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales D, Rennard SI, Nides M, Oncken C, Azoulay S, Billing CB, Watsky EJ, Gong J, Williams KE, Reeves KR. Varenicline, an alpha-4-beta-2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs. sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296:47–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. Changes in cigarette use and nicotine dependence in the United States: evidence from the 2001-2002 wave of the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcoholism and Related Conditions. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1471–1477. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.127886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas AL, Munoz RF, Humfleet GL, Reus VI, Hall SM. Influences of mood, depression history and treatment modality on outcomes in smoking cessation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:563–570. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haug S, Meyer C, Ulbricht S, Schorr G, Rüge J, Rumpf H-J, John U. Predictors and moderators of outcome in different brief interventions for smoking cessation in general medical practice. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Rickert W, Robinson J. Measuring the heaviness of smoking: using self-reported time to the first cigarette of the day and number of cigarette per day. Br J Addict. 1989;84:791–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1989.tb03059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera N, Franco R, Herrera L, Partidas A, Rolando R, Fagerström KO. Nicotine gum, 2 and 4 mg, for nicotine dependence: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial within a behavior modification support program. Chest. 1995;108:447–451. doi: 10.1378/chest.108.2.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollis J, McAfee T, Fellows J, Zbikowski S, Stark M, Riedlinger K. The effectiveness and cost effectiveness of telephone counseling and the nicotine patch in a state tobacco quitline. Tob Control. 2007;16:i53–i59. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.019794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmbeck GR. Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and mediational effects in studies of pediatric populations. J Pediatr Psychol. 2002;27:87–96. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt RD, Sachs DP, Glover ED, Offord KP, Johnston JA, Dale LC, Khayrallah MA, Schroeder DR, Glover PN, Sullivan CR, Croghan IT, Sullivan PM. A comparison of sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1195–1202. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710233371703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Ruiz CA, Masa F, Miravitlles M, Gabriel R, Viejo JL, Villasante C, Sobradillo V. Smoking characteristics: differences in attitudes and dependence between healthy smokers and smokers with COPD. Chest. 2001;119:1365–1370. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.5.1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen JD, Fortmann SP. Role of nicotine dependence in smoking relapse: results from a prospective study using population-based recruitment methodology. Int J Behav Med. 1994;1:320–334. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0104_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski LT, Porter CQ, Orleans CT, Pope MA, Heatherton T. Predicting smoking cessation with self-reported measures of nicotine dependence: FTQ, FTND, and HSI. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1994;34:211–216. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(94)90158-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:877–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RA. Regression with missing X’s: a review. J Am Stat Assoc. 1992;87:1227–1237. [Google Scholar]

- Moorman M, van den Putte B. The influence of message framing, intention to quit smoking, and nicotine dependence on the persuasiveness of smoking cessation messages. Addict Behav. 2008;33:1267–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnoll RA, Patterson F. Sex heterogeneity in pharmacogenetic smoking cessation clinical trials. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;104:s94–s99. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnoll RA, Patterson F, Wilyeto EP, Tyndale RF, Benowitz N, Lerman C. Nicotine metabolic rate predicts successful smoking cessation with transdermal nicotine: a validation study. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009a;92:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SS, Jorenby DE, Fiore FC, Anderson JE, Mielke MM, Beach KE, Piasecki TM, Baker TB. Strike while the iron is hot: can stepped-care treatments resurrect relapsing smokers? J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:429–439. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.3.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strecher VJ, Shiffman S, West R. Moderators and mediators of a Web-based computer-tailored smoking cessation program among nicotine patch users. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8:s95–s101. doi: 10.1080/14622200601039444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz SS, Cowan TM, Klayman JE, Welton M, Leonard BA. Use and effectiveness of tobacco telephone counseling and nicotine therapy in Maine. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:288–294. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toll BA, Martino S, Latimer A, Salovey P, O’ Malley S, Carlin-Menter S, Hopkins J, Wu R, Celestino P, Cummings KM. Randomized trial: quitline specialist training in gain-framed vs standard-care messages for smoking cessation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:96–106. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner LR, Mermelstein R, Hitsman B, Warnecke RB. Social support as a moderator of the relationship between recent history of depression and smoking cessation among lower-educated women. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:201–212. doi: 10.1080/14622200701767738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van ’t Riet J, Ruiter RAC, Werrij MQ, de Vries H. The influence of self-efficacy on the effects of framed health messages. Eur J Soc Psychol. 2008;38:800–809. [Google Scholar]

- Witte K. Putting the fear back into fear appeals -the Extended Parallel Process Model. Commun Monogr. 1992;59:329–349. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S-H, Anderson C, Tedeschi G, Rosbrook B, Johnson CE, Byrd M, Gutiérrez-Terrell E. Evidence of real-world effectiveness of a telephone quitline for smokers. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1087–1093. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa020660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]