Abstract

Purpose

Effective interdisciplinary exchange of patient information is an essential component of safe, efficient, and patient–centered care in the intensive care unit (ICU). Frequent handoffs of patient care, high acuity of patient illness, and the increasing amount of available data complicate information exchange. Verbal communication can be affected by interruptions and time limitations. To supplement verbal communication, many ICUs rely on documentation in electronic health records (EHRs) to reduce errors of omission and information loss. The purpose of this study was to develop a model of EHR interdisciplinary information exchange of ICU common goals.

Methods

The theoretical frameworks of distributed cognition and the clinical communication space were integrated and a previously published categorization of verbal information exchange was used. 59.5 hours of interdisciplinary rounds in a Neurovascular ICU were observed and five interviews and one focus group with ICU nurses and physicians were conducted.

Results

Current documentation tools in the ICU were not sufficient to capture the nurses' and physicians' collaborative decision-making and verbal communication of goal-directed actions and interactions. Clinicians perceived the EHR to be inefficient for information retrieval, leading to a further reliance on verbal information exchange.

Conclusion

The model suggests that EHRs should support: 1) Information tools for the explicit documentation of goals, interventions, and assessments with synthesized and summarized information outputs of events and updates; and 2) Messaging tools that support collaborative decision-making and patient safety double checks that currently occur between nurses and physicians in the absence of EHR support.

Keywords: model development, interdisciplinary communication, intensive care unit, electronic health record

1. Introduction

Health care should be safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable. One of the most important factors to achieve this vision is the effective use of clinical information [1]. Effective communication of patient information in the intensive care unit (ICU) is essential due to the frequent handoff of patient care responsibilities between clinicians, high acuity of patients, complex technologies, complex therapeutic interventions, and the rapidly expanding tsunami of data contained in critical care patient health records [1–4]. These factors combine to form a stressful environment in which individuals from different disciplines must work both autonomously and collaboratively to implement frequent goal-oriented changes for critically ill patients [5, 6]. However, clinical interactions mainly occur within professional disciplines [7] and during stressful situations interdisciplinary collaborations can break down whereby clinicians may retreat into discipline-specific silos [4, 8]. Several groups are tackling the problem of breaking down discipline-specific silos. A United Kingdom (UK) study concluded that improved understanding and utilization of scoring systems that identify trends in a patient's condition may result from an increased understanding of each others' roles and capabilities among ICU interdisciplinary team members [9].

Information overload may be intensified by poorly designed electronic health records (EHRs). EHRs increase access to clinical information across disciplines and may improve evidence-based decision making; however, poorly designed systems may result in increased risk of patient harm [1]. For example, poor system design of EHRs may cause information overload, as clinicians search through an abundance of raw data with only minimal context [1]. Furthermore, while paper and electronic documentation are considered to be the formal record of common goals of patient care [10], constant verbal communication is the predominant method used in the clinical setting to relay patient information and form common goals [11]. To take advantage of the ubiquitous information access and improved communication capabilities offered by EHRs, and to address the problem of communication breakdown, system processes may need to be redesigned [1].

The analysis of communication traffic within clinical care may allow for the development of principles that guide the design and implementation of system processes to support various types of communication and information exchange [11]. Therefore, the purposes of this qualitative study were: 1) To categorize the types of communication and information activities that occur during interdisciplinary communication of ICU common goals in the context of EHR use, and 2) To develop a theoretical model of interdisciplinary information exchange of ICU common goals in the context of EHR use.

2. Background and Theoretical Frameworks

The health record is a channel of communication that provides information to multiple clinicians through the documentation of observations, clinical interviews, assessments, and problem-oriented plans of care. Entering and reviewing information in the health record enables clinicians to establish common ground (i.e., shared understanding) and exchange critical information [11]. However, when providing clinical care many tasks exist that require unplanned verbal information exchange or information seeking, which may lead to a high level of unnecessary interruptions [11, 12]. Moreover, verbal information exchange is subject to information loss [3].

Hazlehurst defined six categories of verbal information exchange in an activity system as: 1) Directing an action that seeks to transition the activity system to a new state; 2) Sharing goals about an expectation of a desired future state; 3) Conveying shared understanding about the status of the current state; 4) Alerting about abnormal or surprising information about the current state; 5) Explaining a rationale for the current state; and 6) Reasoning to solve problems and understand the current state of the system [13]. The categorization of information exchange in the ICU and the mapping of these categories to the appropriate type of communication channel may inform the development of EHR technologies to support communication and decrease interruptions and information loss.

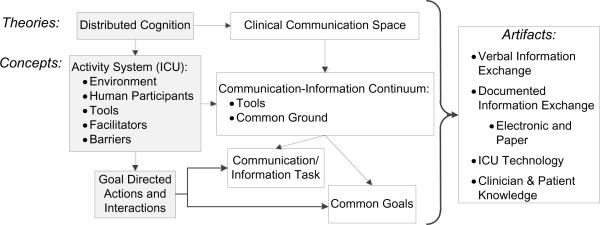

The integrated theoretical frameworks of Coiera's clinical communication space [11] and distributed cognition [14] allow us to better understand interdisciplinary communication and nurses' and physicians' goal-directed actions and interactions. Figure 1 shows the intersection of the distributed cognition and clinical communication space theoretical frameworks. The shaded boxes represent concepts from the distributed cognition framework. In contrast to traditional cognitive frameworks that only describe individual processes, the integration of these two frameworks encompasses artifacts (e.g., electronic and paper-based documentation), patterns of information flow at the individual level, and goal-directed actions and interactions within an activity system, such as a clinical unit [14]. The clinical communication space seeks to explain how individual tasks can be modeled along a communication-information continuum. This continuum posits that a task may be anticipated and represented using information tools (e.g., nursing flowsheet data) if common ground has been established amongst the individuals communicating about that task. Conversely, a task that is not easily anticipated or structured (e.g., an unexpected patient response to an intervention) requires communication tools (e.g., telephone or interactive messaging) if common ground has not yet been established amongst the individuals communicating about that task. The prior establishment of common ground is referred to as “pre-emptive grounding,” and the need to establish common ground at the time of an interaction is referred to as “just-in-time grounding” [11].

Figure 1.

Integrated Distributed Cognition and Clinical Communication Space Frameworks.

A distributed cognition analysis of an activity system (i.e., ICU) involves a user analysis, a functional analysis, a task analysis, and a representational analysis. User analysis characterizes the division of labor, overlap of knowledge and skills, and patterns of communication and social interaction which are essential elements for understanding the interactive functioning of the environment as a whole [15]. Functional analysis describes the domain knowledge and structure among individuals (i.e., clinicians) and artifacts (i.e., ICU interdisciplinary morning rounds and documentation). In this study, the functional analysis of the ICU activity system describes the domain knowledge (e.g., common ground established related to goals of patient care) that were discussed during ICU interdisciplinary morning rounds and documented by clinicians, and the structure of those discussions and documentation. Task analysis expands on the functional analysis to analyze the type of information exchanged among clinicians and to analyze the compatibility of information exchange between ICU interdisciplinary morning rounds and documentation. Representational analysis describes the most efficient representation of information to support effective information exchange among clinicians and documentation artifacts within the activity system [15]. Each task and its representation can be modeled using Coiera's communication-information continuum [11], depending on the amount of common ground among the communicators, as either a structured task that requires an information tool or an unstructured task that requires a communication tool.

3. Methods

This study used ethnographic observation techniques, focus groups and interviews to identify and analyze goal-directed actions and interactions related to interdisciplinary communication of common goals (i.e., goals of patient care that are shared among members of the interdisciplinary care team) in the ICU. This study took place between November 2008 and May 2009 on an 18-bed neurovascular ICU (NICU) at a large urban teaching hospital that used a commercial EHR for nurse and physician documentation. Clinicians were observed during interdisciplinary ICU morning rounds (i.e., discussions of each patient's status and plan of care by the ICU team) from 7:30 am until 12 pm. During the observations the investigator recorded the clinicians' goal-directed actions and interactions via handwritten field notes, which were then transcribed into an electronic document. Focus group and interviews were held with ICU clinicians in which the participants were asked about interdisciplinary communication related to patient goals in the ICU. Member checks were conducted during the interviews to ensure accurate interpretation of the participants' words. Audio-recordings of the focus group and interviews were transcribed verbatim by a paid transcriptionist and were verified against the audio-recordings for accuracy. Data collection continued until data saturation was achieved [16]. ATLAS.ti™ (GmbH Berlin, Version 5.5.9) software was used for the analysis of the observational, interview, and focus group data. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained prior to data collection and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data analysis and model development consisted of five steps: 1) Distributed cognition analysis (i.e., user, functional, task, representational), 2) Mapping Hazlehurst's six categories of information exchange [13] (referred to as Information Exchange Categories in this study) to the user, functional, task and representational analyses, 3) Analysis of the appropriate type of grounding (i.e., pre-emptive or just-in-time grounding) needed for each type of task and representation based on Information Exchange Categories, 4) Communication-information continuum analysis for each information exchange task based on the type of grounding needed, and, 5) Model development of EHR Interdisciplinary Information Exchange of ICU Common Goals based on data analysis.

4. Results

Registered nurses, attending physicians (equivalent to UK consultants), fellow physicians (post-medical residency sub-specialty trainees), resident physicians (equivalent to UK senior or junior house officers), pharmacists, medical students, and nursing students were observed during NICU interdisciplinary rounds for a total 59.5 hours over 16 days. One focus group of 8 NICU nurses and key informant interviews with 1 ICU nurse and 4 ICU residents were conducted. The focus group and each interview lasted approximately one hour. The presentation of the results is organized by: 1) User analysis and mapping to Information Exchange Categories; 2) Functional analyses and mapping to Information Exchange Categories; 3) Functional analysis: facilitators and barriers; 4) Task analysis and representational analysis and mapping to Information Exchange Categories; 5) Common ground and communication-information continuum analyses; 6) Model of EHR Interdisciplinary Information Exchange of ICU Common Goals.

4.1 User Analysis and Mapping to Information Exchange Categories

ICU nurses and physicians held a shared mental model of common goals and division of labor enabled tasks to be completed and a vast amount of information to be exchanged to ensure that patient care plans did not fall behind. Information exchange patterns among the clinicians fell into three main categories: 1) Planned verbal discussions that occurred multiple times per day during ICU rounds and handoffs, 2) Unplanned verbal discussions of expected and unexpected patient updates, and, 3) Information exchanged via the EHR (see Table I for mapping of user analysis to Information Exchange Categories).

Table I.

User and Functional Analysis and Mapping to Information Exchange Categories.

| Interdisciplinary Communication | Information Exchange Categories1 |

|---|---|

| User analysis | |

| Shared mental model of patient outcome | 2 |

| Division of labor | 1 & 4 |

| Planned verbal discussions | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 & 6 |

| Unplanned verbal discussions | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 & 6 |

| Information exchange via the EHR | 1,2, & 4 |

| Functional analysis | |

| Collaborative decision-making | 2 & 6 |

| Updates between disciplines | 1, 3, 4, & 5 |

Information Exchange Categories [13]

Directing an action that seeks to transition the activity system to a new state

Sharing goals about an expectation of a desired future state

Conveying shared understanding about the status of the current state

Alerting about abnormal or surprising information about the current state

Explaining a rationale for the current state

Reasoning to solve problems and understand the current state of the system

The clinicians' shared mental model was demonstrated during the observations by their use of conversational grounding techniques [17] and a shared language with clinical- and ICU- specific abbreviations to “share goals about an expectation of a desired future state” [13] such as a patient's status and outcome. Unplanned verbal discussions happened “on the spot,” and occurred within or between disciplines (e.g., nurses and physicians) to coordinate updates or to notify one another of information that may have been missed (for example, if a nurse was unable to attend interdisciplinary rounds due to immediate patient care responsibilities). These unplanned updates were, according to one resident, “dependent on the amount of effort exerted by--and the competency level of--the resident and the nurse, and the patient status.” During both planned and unplanned discussions, clinicians were observed to exchange information in a manner consistent with all of Hazlehurst's Information Exchange Categories (see Table I). Additionally, the EHR was used by nurses and physicians for information exchange to: 1) Direct an action (e.g., place orders electronically); 2) Share goals (e.g., plan of care documented in attending ICU note); and 3) Alert about abnormal or surprising information (e.g., abnormal laboratory values).

4.2 Functional Analysis and Mapping to Information Exchange Categories

During planned and unplanned verbal discussions, domain knowledge (e.g., nursing-specific knowledge or physician-specific knowledge) was exchanged during open discussions to solve problems and understand the patient's status. ICU rounds were structured such that the resident physician presented the patient's past medical history, diagnosis, treatments, laboratory and study results, clinical assessment and events during the prior 24 hours. After the resident's presentation, collaborative decision-making occurred among nurses and physicians to generate the goals for the next 24 or more hours, and these goals were then documented by the attending physician in the EHR. A brief example of this process was observed where a resident proposed a plan to switch a patient's antibiotic therapy. The patient's nurse stated: “No, I wouldn't want to make too many changes at once.” To this, the attending physician replied, “Yes, I would wait.”

Updates between disciplines were exchanged primarily through verbal discussions during and between rounds. One nurse explained: “whether or not some documentation is updated is variable, but [we try] to always verbally communicate the updates to each other.” During ICU rounds, the nurses' verbal updates: 1) Conveyed a shared understanding to the team about unstable patients who had immediate needs requiring the attention of the interdisciplinary team; 2) Alerted the team about orders that needed to be entered into the computerized provider order entry (CPOE) system; and, 3) Summarized and explained rationales to the team regarding a patient's progress based on contextual information about the patient status for the evaluation of goals (see Table I). For example, in one instance, a nurse interrupted rounds and stated to the attending physician: “You need to round on [see] Mr.___ next; his [neurological] exam is not good.” In another case, the nurse explained a rationale about the patient's status that contextualized laboratory values, vital signs, and ultimately the plan of care, to the interdisciplinary team by explaining: “He is much more alert when he is hypertensive.”

4.3 Functional Analysis: Facilitators and Barriers to Common Goals Coordination

The nurses stated that, if they were not present at rounds, they would piece together the plan and infer goals from their own assessment, the attending physician's note, the resident's sign-out, nurse's shift report, orders, and ICU standards “that we all know” (see Table II). This perception of standards “that we all know” assumes that “sharing goals about an expectation” has already occurred through pre-emptive grounding obtained from clinical experience and the process of the ICU learning curve. Based on these standards, nurses and residents were expected to individually anticipate common goals and used their autonomy “to transition the activity system to a new state” [13]. For example, when the nurse deemed it clinically appropriate, he or she initiated weaning a patient's intravenous sedation or ventilator settings before rounds to allow for the ICU team to evaluate the patient's response to these interventions during rounds. Moreover, the ICU team expected that the nurse would initiate interventions and double-check orders, based on standards “that we all know”, in order to, as one nurse stated, “move things along” before, during and after rounds.

Table II.

Functional Analysis of Facilitators and Barriers of ICU Interdisciplinary Exchange with quotations from focus groups and interviews

| Facilitators | Quote |

|---|---|

| Standards “we all know” |

Nurse: In a subspecialty unit like ours, there are certain standards that we all know and follow. Resident: I think there's a lot of unspoken [communication], like, `this is what we're doing: We're giving a little albumin; we're waking them up.' And sometimes it's said, sometimes it's just implied. |

| Autonomy |

Nurse: I'll say to them, “Well I'm going to CPAP‡ this guy and see how he does.” Because we have people that have been intubated for extended periods…You know, move things along. And there's no formal order for that. I mean, I don't think I've seen an order. Resident: [During rounds] a resident can easily enter orders on the wrong patient or confuse orders because they are catching up on previous patients…there are some good pharmacy checks and there are good nursing checks, [that] is the way…that orders are done correctly. |

| Barriers | Quote |

|---|---|

| System of ad hoc updates |

Nurse: “it doesn't all get written down [at rounds] and the night nurses don't know, sometimes in the report it gets lost in transition…you work twelve hours with one eye closed, basically not having all the information with you.” Resident: If it's a chronic patient, and there's a sense that something might change today, I don't know if that's necessarily communicated, [but a] very acute issue, usually people are very much in sync about. |

| Implied and outdated goals |

Resident: A third of the time, usually the event is communicated verbally and the issues or treatment and results are communicated verbally again, but nothing's ever written down. Nurse: The computer system doesn't even remotely match what's going on with the patient. It's ridiculous; there'll be Cardizem hanging [intravenous medication] and no orders for it [in CPOE system]. |

| Inefficient information retrieval |

Resident: It's a lot faster and easier to ask `Please, just verbally, quickly tell me what's going on.' Nurse: Things are delayed for any patient, stable or unstable because of rounds…[the residents] won't put it [CPOE order] in until after rounds are over. Resident: The [paper-based bedside chart] of the nurse's notes…past medical history and pertinent events… a log of what happened. If I know a specific event happened, and I'm trying to get more details, that's where I may go. |

CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure is used to attempt to discontinue ventilator support while the patient remains intubated.

The ICU involved in the study operated using a system of ad hoc updates (see Table II). Besides planned verbal discussions, nurses and residents stated that there was not a good system in place to make sure that: 1) The nursing and the medical team's division of labor and directions of actions are in accord, 2) Alerts and updates are received, and 3) Problems are solved and progress is evaluated. The clinicians agreed that goals are “often only implied in a CPOE order…may be missed, forgotten or not prioritized as intended” and, especially for chronic patients, are often outdated (see Table II). For example, during the observations the attending was not aware that a patient who had been on a ventilator for several days had been well enough for extubation for the past 24 hours. The clinicians' perceived that EHR information retrievalwas inefficient compared to verbal information exchange or paper-based notes (e.g., personal notes, to-do lists, and information printed from the EHR). These barriers indicated that the current structure of the EHR was not sufficient to meet every Information Exchange Category.

4.4 Task and Representational Analyses and Mapping to Information Exchange Categories

Ten interdisciplinary information exchange tasks were identified: 1) Interventions, 2) Explicit goals, 3) Implied goals, 4) Patient safety double-checks, 5) Vital signs, 6) Clinical findings, 7) Laboratory values, 8) Updates of events, 9) Evaluation of goals, and 10) Collaborative decision-making. Interventions, explicit goals, implied goals, clinical findings and updates of events each had multiple representations within electronic and paper-based documentation. In contrast, the information tasks vital signs, laboratory values and collaborative decision-making each had one representation. Patient safety double-checks and the evaluation of goals, as described by the clinicians during the focus group and interviews and noted during observations, were not represented in the electronic or paper-based documentation but were verbally exchanged. Table III identifies the mapping of these tasks and representations to Information Exchange Categories.

Table III.

ICU Information Exchange Mapped to Communication-Information Continuum

| Task Analysis of Goal Information Exchange | Representational Analysis within EHR or paper documentation | Information Exchange Categories [13] | Appropriate Type of Grounding | Communication-Information Continuum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| • Interventions | Multiple Representations: EHR flowsheets, CPOE orders, Attending EHR note, Resident EHR sign-out‡, Nurse bedside paper-based chart, miscellaneous notes | Directing an action | Pre-emptive | Information tools |

| • Explicit goals | Multiple Representations: CPOE orders, Attending EHR note | Sharing goals | Pre-emptive | Information tools |

| • Implied goals | Multiple Representations: EHR flowsheets, CPOE orders, Attending EHR note, Resident EHR sign-out, Nurse bedside paper-based chart, miscellaneous notes | Sharing goals | Pre-emptive | Information tools |

| • Patient safety double checks | None | Conveying shared understanding | Just-in-time | Communication tools |

| • Vital signs | One representation: EHR flowsheets | Alerting about abnormal or surprising information | Pre-emptive | Information tools |

| • Clinical Findings | Multiple Representations: EHR flowsheets, Attending EHR note, Resident EHR sign-out, Nurse bedside paper-based chart, miscellaneous notes | Alerting about abnormal or surprising information | Pre-emptive | Information tools |

| • Laboratory values | One representation: EHR laboratory data | Alerting about abnormal or surprising information | Pre-emptive | Information tools |

| • Updates of events | Multiple Representations: EHR flowsheets, Attending EHR note, Resident EHR sign-out, Nurse bedside paper-based chart, miscellaneous notes | Alerting about abnormal or surprising information | Pre-emptive | Information tools |

| • Evaluation of goals | None | Explaining a rationale | Pre-emptive | Information tools |

| • Collaborative decision-making | One representation Attending EHR note | Reasoning to solve problems and understand | Just-in-time | Communication tools |

Sign out = end of shift report

4.5 Common Ground and Communication-Information Continuum Analyses

Directing an action such as an intervention; sharing goals explicitly or implicitly; alerting about abnormal or surprising information such as vital signs, clinical findings, laboratory values, or updates of events; and explaining a rationale such as during the evaluation of goals, are all formal types of information exchange within the ICU and all of them require “pre-emptive grounding” [11]. Pre-emptive grounding was attained through a learning process in the ICU of obtaining clinical experience and knowledge of ICU standards “that we all know”, which allowed for the interpretation of data obtained from information tools such as flowsheets.

There were also information exchange activities that require communication tools that allow for communicating individuals to establish common ground at the time of the interaction (i.e., just-in-time grounding) [11]. These types of information exchange were: 1) Patient safety double-checks for conveying shared understanding to ensure that an order was entered as intended by another individual, and 2) Collaborative decision-making to reason and solve problems and understand the current patient status.

4.6 Model of EHR Interdisciplinary Information Exchange of ICU Common Goals

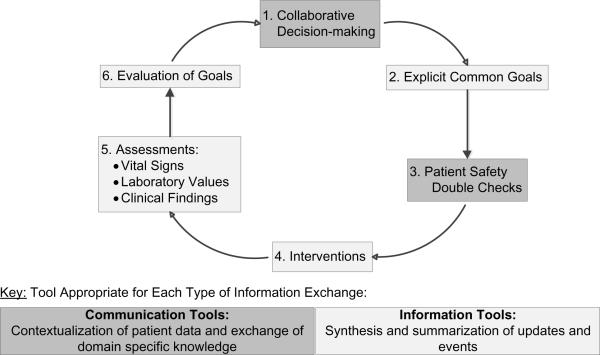

The structure for representing vital signs and laboratory values was clear and consistent in the EHR. However, other communication and information tasks would benefit from modifying or adding communication and information channels to the EHR. Overall, there were three inadequate structures to represent information and communication in the ICU activity system: 1) Information and communication tasks that were not represented in the EHR (i.e., patient safety double checks, evaluation of goals), 2) Communication tasks that were represented in the EHR by only one discipline (i.e., collaborative decision-making on Attending ICU note), and 3) Information tasks that had multiple EHR and paper-based representations (i.e., interventions, explicit and implicit goals, clinical findings, and updates of events). The developed model in Figure 2 proposes solutions to the challenges of inadequate information exchange and representation of common goals information in the ICU. The model shows a cyclical process that includes six stages: 1) Collaborative decision-making, 2) Explicit common goals, 3) Double checks, 4) Interventions, 5) Assessments (vital signs, laboratory values, clinical findings), and 6) Evaluation of goals. This model supports the development of: 1) EHR information tools that synthesize and summarize updates and events related to explicit goal generation, implementation, assessment, and evaluation; and, 2) Communication tools that allow for clinicians to contextualize patient data and exchange domain specific knowledge for collaborative decision-making and patient safety double checks twenty-four hours per day (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Model of EHR Interdisciplinary Information Exchange of ICU Common Goals

5. Discussion

This study integrated the theoretical frameworks of distributed cognition and the clinical communication space which was then used to analyze information exchange in the ICU, to map our analysis to Hazlehurst's Information Exchange Categories, and to determine the appropriate place on the communication-information continuum for each interdisciplinary information exchange task. These analyses informed the development of the model of EHR Interdisciplinary Information Exchange of ICU Common Goals.

This study found that the current structure and content of the EHR was observed and perceived by clinicians to be insufficient for the capture of interdisciplinary information exchange of common goals that occurred during and between ICU interdisciplinary morning rounds and this may have resulted in increased clinician reliance on verbal communication. Verbal communication allows for information exchange and decision-making to keep up with the continuously changing demands of ICU patient care and can be an appropriate medium for clinical information exchange. However, reliance on verbal discussions may lead to interruptions that require rescheduling, influence errors of omission, or influence a clinician's lack of recall [11, 12]. Interruptions, errors of omission, and information loss may be minimized by determining information exchange activities that are frequently met through verbal communication, yet, may be supported through information or communication tools. Moreover, electronic documentation that efficiently captures and represents clinical information as a process of patient care is consistent with the “meaningful use” aims of the U.S.'s Centers for Medicare & Medicare Services and the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology's and the UK's National Health Service's Care Record Service (NHS CRS) [1, 18].

ICU care is a twenty-four-hour-a-day job, yet the clinicians who participated in this study indicated that formal structures for decision-making take place almost exclusively during the day shift. In general, fewer clinicians are present on ICUs at night, yet, patients are equally unstable [19]. The data suggests the need to support and capture the decision-making of night-shift clinicians to maintain continuity of information exchange. Communication and information tools that inform clinicians of decisions that were made throughout the day and allow for their input about decisions and changes made throughout the night may enhance continuity of care and minimize information loss. Shifting common ground between clinicians was found and may be dependent on the patient's clinical status (acute versus chronic patients) which may have important implications for the development of informatics tools to facilitate communication in the ICU [11]. An interesting concept of interdisciplinary collaboration to further investigate may be to understand clinicians' perceived responsibility to follow-up on decisions (e.g., patient safety double checks) that were made in the absence of one or more clinicians and are not clearly reflected in the EHR (e.g., goals implied in CPOE orders) to determine best practice recommendations to prevent information loss and increase patient safety.

Restrictions imposed by EHR structure have been shown to cause nurses to omit critical domain knowledge and contextual information necessary for the correct interpretation of structured data content [20]. We observed nurses' autonomy and decision making in action, yet found that those actions and decision-making were not reflected in the EHR. This lack of visibility of autonomous actions and decision-making may impede understanding of patient care processes and outcomes that make care more efficient, effective, and safe.

Furthermore, the presence of an authority gradient (e.g., hesitation to disagree with someone of perceived higher authority) is well documented in aviation and aerospace and was introduced in the Institute of Medicine report To Err is Human as a concept of concern in health care due to its role in contributing to potential medical errors [21, 22]. Mitchell and colleagues concluded that the health of individuals may be better served by modeling, for all clinical disciplines, an individualized patient-centered approach to documentation [23]. Future work should analyze the potential facilitating role that patient-centered EHR communication may have in relation to a clinician's expression of a dissenting view about a clinical decision due to a perceived authority gradient [21].

The multiple representations of interventions, goals, clinical findings, and updates of events are useful for providing redundancy that ensures robustness and correctness in the functions performed by a system [24]. However, a functional system should enhance situational awareness due to the coordination demands of task work that create interactions that communicate situational information [24]. Therefore, a system that simply provides a “tsunami” of data without integration or synthesis may decrease situational awareness. This lack of situational awareness is akin to a lack of common ground which, according to the communication-information continuum, is not an appropriate setting for the use of information tools [11]. Synthesis and summarization of contextually relevant clinical output via information tools of goals generated, implementations, assessments, and evaluations may increase situational awareness and continuity of care. These information tools may be semi-structured with the option to select pre-defined patient care goals or enter patient-tailored goals via free-text entry. Interactive and secure online messaging via communication tools accessed through ubiquitous computing technologies may minimize interruptions, information loss, and delays to patient care throughout the day and night [25]. Therefore, the appropriate implementation of these information and communication tools may support EHR data to flow as vibrantly and change as quickly as patient care activities and decision-making in the ICU (see Figure 2).

5.1 Limitations

The limitations of this study were the single ICU setting from which data were collected and the fact that observations were conducted only during the day shift. However, the triangulation of sixty hours of observational data with the saturated data from the nurse focus group and clinician interviews increases confidence in the discussed themes and conclusions drawn from this study. In addition, data identified in the analysis of interdisciplinary information exchange was consistent with Hazlehurst's distributed cognition analysis of clinical information exchange during cardiac surgery [13]. Therefore, the conclusions may be transferrable to interdisciplinary information exchange for critical care patients in large teaching hospitals that use a commercial EHR.

6. Conclusion

Current documentation tools in the NICU are not sufficient to capture the interdisciplinary coordination and verbal communication of goal-directed actions and interactions that occur during, and between, ICU interdisciplinary morning rounds. EHR documentation is often not up-to-date and is not efficient for clinicians to retrieve. These challenges result in a further reliance on verbal information exchange which may lead to interruptions, errors of omission, and information loss [11, 12]. However, collaborative decision-making was a frequent patient care activity that occurred between nurses and physicians in the form of planned and unplanned verbal information exchange. The model of EHR Interdisciplinary Information Exchange of ICU Common Goals posits that EHRs should support: 1) The explicit documentation of unified common patient goals, interventions, assessments, and evaluations with synthesized and summarized information outputs of events and updates; 2) Messaging tools that support the individualized patient-centered care processes of collaborative decision-making and patient safety double checks that currently occur between nurses and physicians in the absence of EHR support. Future work should include the continued development of models to support patient-centered collaborative decision making, goal generation, implementation, assessment and evaluation as new EHR technologies are introduced to the ICU. Future work should also support the development and use of information exchange models for EHR development, implementation, and evaluation.

10. Summary Table.

What was already known on the topic

ICU Interdisciplinary information exchange is complex, but essential to safe and efficient patient care.

Verbal communication is a frequent method of clinical information exchange, but is subject to information loss.

Poor system design of EHRs may cause information overload.

What this study added to our knowledge

The electronic health record (EHR) in the ICU is inefficient for information retrieval and not sufficient for collaborative decision-making.

EHRs should support information tools for goal, intervention, and assessment documentation and messaging tools for collaborative decision-making and patient-safety communication.

8. Acknowledgements

This project was supported by National Institute for Nursing Research T32NR007969 and D11 HP07346. Dr. Collins is supported by T15 LM 007079. We thank the NICU clinicians who participated in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

9. Statement on Conflicts of Interest The authors have no conflicts of interest.

11. References

- [1].National Research Council . Computational Technology for Effective Health Care: Immediate Steps and Strategic Directions. The National Academies Press; Washington, D.C: 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Strople B, Ottani P. Can technology improve intershift report? What the research reveals. J Prof Nurs. 2006;22:197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Arora V, Johnson J, Lovinger D, Humphrey HJ, Meltzer DO. Communication failures in patient sign-out and suggestions for improvement: a critical incident analysis. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14:401–7. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.015107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Pronovost P, Wu A, Sexton J. Acute decompensation after removing a central line: practical approaches to increasing safety in the intensive care unit. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140:1025–33. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-12-200406150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Patel VL, Zhang J, Yoskowitz NA, Green R, Sayan OR. Translational cognition for decision support in critical care environments: a review. J Biomed Inform. 2008;41:413–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Humbert J, Gallagher K, Gabbay R, Dellasega C. Intensive insulin therapy in the critically ill geriatric patient. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2008;31:14–8. doi: 10.1097/01.CNQ.0000306391.94529.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Creswick N, Westbrook JI, Braithwaite J. Understanding communication networks in the emergency department. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:247. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Stein-Parbury J, Liaschenko J. Understanding collaboration between nurses and physicians as knowledge at work. Am J Crit Care. 2007;16:470–7. quiz 478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Donohue LA, Endacott R. Track, trigger and teamwork: communication of deterioration in acute medical and surgical wards. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 26:10–7. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Raja U, Mitchell T, Day T, Hardin JM. Text mining in healthcare. Applications and opportunities. J Healthc Inf Manag. 2008;22:52–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Coiera E. When conversation is better than computation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2000;7:277–86. doi: 10.1136/jamia.2000.0070277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Collins S, Currie L, Patel VL, Bakken S, Cimino JJ. Multitasking by clinicians in the context of CPOE and CIS use. Medinfo. 2007;12:958–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hazlehurst B, McMullen CK, Gorman PN. Distributed cognition in the heart room: how situation awareness arises from coordinated communications during cardiac surgery. J Biomed Inform. 2007;40:539–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hutchins E. Cognition in the Wild. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zhang J, Patel VL, Johnson K, Smith J, Malin J. Designing Human-Centered Distributed Information Systems. IEEE Intelligent Systems. 2002;17:42–47. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Brod M, Tesler LE, Christensen TL. Qualitative research and content validity: developing best practices based on science and experience. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:1263–78. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9540-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Clark H, Brennan S. Grounding in Communication. In: Resnick L, Levine J, Teasley S, editors. Perspectives on Socially Shared Cognition. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Cresswell K, Sheikh A. The NHS Care Record Service (NHS CRS): recommendations from the literature on successful implementation and adoption. Inform Prim Care. 2009;17:153–60. doi: 10.14236/jhi.v17i3.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Tobin AE, Santamaria JD. After-hours discharges from intensive care are associated with increased mortality. Med J Aust. 2006;184:334–7. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2006.tb00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kim H, Harris MR, Savova GK, Chute CG. The first step toward data reuse: disambiguating concept representation of the locally developed ICU nursing flowsheets. Comput Inform Nurs. 2008;26:282–9. doi: 10.1097/01.NCN.0000304839.59831.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Cosby KS, Croskerry P. Profiles in patient safety: authority gradients in medical error. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:1341–5. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].IOM . To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. In: Corrigan J, Kohn LT, Donaldson M, editors. The Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. National Academies Press; Washington D.C.: 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Mitchell B, Petrovskaya O, McIntyre M, Frisch N. Where is nursing in the electronic health record? In: McDaniel JG, editor. Advances in Information Technology and Communication in Health: ITCH 2009. Steering Committee; IOS Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hazlehurst B, McMullen C, Gorman P, Sittig D. How the ICU follows orders: care delivery as a complex activity system. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2003:284–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Baggs JG, Schmitt MH. Nurses' and Resident Physicians' Perceptions of the Process of Collaboration in an MICU. Research in Nursing and Health. 1997;20:71–80. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199702)20:1<71::aid-nur8>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]