Abstract

Oestrogen (17β-oestradiol, E2) is a highly effective treatment for experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) that may potentiate Foxp3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells, which in turn limit the expansion of encephalitogenic T-cell specificities. To determine if Treg cells constitute the major non-redundant protective pathway for E2, we evaluated E2 protection of EAE after targeted deletion of Foxp3 expression in Foxp3-DTR mice. Unexpectedly, E2-treated Foxp3-deficient mice were completely protected against clinical and histological myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG)-35-55 peptide-induced EAE before succumbing to diphtheria toxin-induced mortality. This finding indicated the presence of alternative E2-dependent EAE-protective pathways that could compensate for the lack of Treg cells. Further investigation revealed that E2 treatment inhibited proliferation and expression of CCL2 and CXCL2, but enhanced secretion of interleukin-10 (IL-10) and IL-13 by MOG-35-55-specific spleen cells. These changes occurred concomitantly with increased expression of several chemokines and receptors, including CXCL13 and CXCR5, and the negative co-activation molecules, PD-L1 and B7.2, by B cells and dendritic cells. Furthermore, E2 treatment resulted in higher percentages of spleen and lymph node T cells expressing IL-17, interferon-γ and tumour necrosis factor-α, but with lower expression of CCR6, suggesting sequestration of MOG-35-55 peptide-specific T cells in peripheral immune organs. Taken together, these data suggest that E2-induced mechanisms that provide protection against EAE in the absence of Foxp3+ Treg cells include induction of regulatory B cells and peripheral sequestration of encephalitogenic T cells.

Keywords: B cells, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, Foxp3-DTR, Foxp3, oestrogen

Introduction

The role of gender and hormones as determinants in the development of autoimmunity has been studied extensively,1–3 with a higher frequency of disease susceptibility among women than men. Also, remission during pregnancy when oestrogen (E2) levels are elevated followed by post-natal relapses suggest that this hormone exerts a regulatory effect on autoimmune diseases.4 Oestrogen treatment arrests clinical manifestations of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE)5 as well as collagen-induced arthritis6 mediated by oestrogen receptor-α but not oestrogen receptor-β.7,8

Regulatory T (Treg) cells expressing the transcription factor, Foxp3, form a subset of CD4+ T cells that help to maintain immune tolerance, thereby controlling autoimmunity9,10 and when depleted, worsening the severity of EAE in mice.11 Also, Treg cells can down-regulate or lose expression of Foxp3, allowing these cells to become activated and produce pro-inflammatory cytokines.12 In EAE, the treatment effect of E2 is augmented through the expansion of Treg cells13 via up-regulation of programmed death-1 (PD-1).14,15 To further understand this phenomenon, we obtained Foxp3-diphtheria toxin receptor (DTR) mice in which Treg cells can be selectively depleted by administration of diphtheria toxin (DT).16 Surprisingly, ablation of Treg cells did not abolish the protection conferred by 17β-oestradiol, indicating that alternative mechanisms compensate for the lack of the Treg cells. In this study, we provide new insights into mechanisms that contribute to E2-mediated protection when Treg cells are absent.

Materials and methods

Animals

Foxp3-DTR mice were generated from breeding pairs obtained from Dr Alexander Rudensky (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY). The Foxp3-DTR strain has been characterized and described in detail by Kim et al.16 Briefly, Foxp3-DTR mice were generated by inserting the human DTR into the untranslated portion of Foxp3. This knock-in permits selective depletion of Foxp3+ Treg cells by administering DT. Following administration of DT, the group further characterized this strain and identified splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy as well as massive cellular infiltration in several organs. The mice were housed in the Animal Resource Facility at the Portland Veterans Affairs Medical Center in accordance with institutional guidelines. The study was conducted in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines for the use of experimental animals, and the protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Hormone treatment, induction of EAE and administration of DT

One week before immunization with 200 μg myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG)-35-55 peptide (PolyPeptide Laboratories, San Diego, CA) in 200 μg complete Freund's adjuvant (H37Ra; Difco, Detroit, MI), Foxp3-DTR female mice were implanted with 2·5 mg 60-day release 17β-oestradiol pellets or placebo pellets (Innovative Research of America, Sarasota, FL). Placebo pellets contain all the components of the hormone pellets except the 17β-oestradiol itself. Mice received pertussis toxin (Ptx; List Biologicals, Campbell, CA) on the day of immunization (75 ng) and 2 days later (200 ng). Animals were monitored daily for clinical signs of disease and scored using the following scale: 0 = normal; 1 = limp tail or mild hind limb weakness; 2 = moderate hind limb weakness or mild ataxia; 3 = moderately severe hind limb weakness; 4 = severe hind limb weakness or mild forelimb weakness or moderate ataxia; 5 = paraplegia with no more than moderate forelimb weakness; and 6 = paraplegia with severe forelimb weakness or severe ataxia or moribund condition. At the onset of clinical signs of EAE, both placebo and E2-implanted mice were injected with 1 μg DT intraperitoneally on days 0, 1 and 3 relative to onset.

Histopathology

The intact spinal column was removed from mice at the end of three DT treatments and was fixed in 10% formalin. Spinal cords were dissected after fixation and were embedded in paraffin before sectioning. The sections were stained with Luxol Fast Blue/periodic acid-Schiff/haematoxylin & eosin to assess demyelination and inflammatory lesions and analysed by light microscopy. Semi-quantitative analysis of inflammation and demyelination was determined by examining at least nine or ten sections from each mouse spinal column.

Flow cytometry

Spleens were harvested from mice given placebo Foxp3-DTR + DT and Foxp3-DTR + DT + E2 after three DT treatments and cells were washed and resuspended in staining medium (1× PBS, 0·5% BSA, 0·02% sodium azide). Cells were then stained with a combination of the following antibodies: CD4 (L3T4), CD19 (1D3), CD11c (HL-3), Gr-1(IA8), PD-1 ligand 1 (PD-L1; MIH5), B7.2 (CD86, GL1), B7.1 (CD80, 16-10A1), CCR6 and Foxp3 for 10 min at 4°. After incubation with monoclonal antibody, cells were acquired on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Intracellular staining of Foxp3 was completed following overnight incubation in fixation/permeabilization buffer as per the manufacturer's instructions (eBiosciences, San Diego, CA). For intracellular cytokine detection, cells were stimulated for 5 hr with leucocyte activation cocktail (BD Biosciences Cat#550583). Cells were stained with surface markers and then fixed using the Fix/perm buffer overnight at 4°. Cells were then washed with 1 × permeabilization buffer and stained with monoclonal antibodies specific for tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interferon-γ (IFN-γ) or interleukin-17 (IL-17). Forward and side scatter parameters were chosen to identify lymphocytes. Dead cells were gated out using propidium iodide discrimination. Cells were gated on CD19 and CD11c to determine expression of B7.1 and B7.2 and data were analysed using FCS express software (De Novo Software, Los Angeles, CA).

Proliferation assay

Splenocytes collected from Foxp3-DTR + DT and Foxp3-DTR + DT + E2 mice were plated onto 96-well flat bottom plates at a density of 400 000 cells per well. Cells were stimulated with 10 or 50 μg/ml MOG-35-55 peptide for 72 hr, the last 18 hr in the presence of [3H]-thymidine. Cells were then harvested onto filter mats and read on a Perkin Elmer micro-beta scintillation counter. Stimulation indices were determined by calculating the ratio of antigen-specific counts/min to medium alone counts/min.

Cytokine detection by Luminex bead array

Single-cell suspensions of spleen and lymph node cells from placebo Foxp3-DTR + DT and Foxp3-DTR + DT + E2 mice were cultured in the presence of 25 μg/ml MOG-35-55 peptide for 48 hr. Culture supernatants were assessed for cytokine levels using a Luminex Bio-Plex cytokine assay kit (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA) following the manufacturer's instructions.

RNA isolation and reverse transcription-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from spleens of Foxp3-DTR + DT and Foxp3-DTR + DT + E2 mice using the RNeasy mini kit protocol (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and converted into cDNA using oligo-dT, random hexamers, and Superscript RT II (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). Real-time PCR was performed using TaqMan PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and primers. Reactions were conducted on the ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) to detect mRNA quantified as relative units compared with the glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase reference gene. Pre-designed Taqman primers for CCL2, CXCL2, CXCL10, CXCL13, CCR1, CCR2, CCR3, CCR5, CCR6 and CXCR5 were obtained from Applied Biosystems.

Results

E2 mediated protection of EAE is not mediated through Foxp3 alone

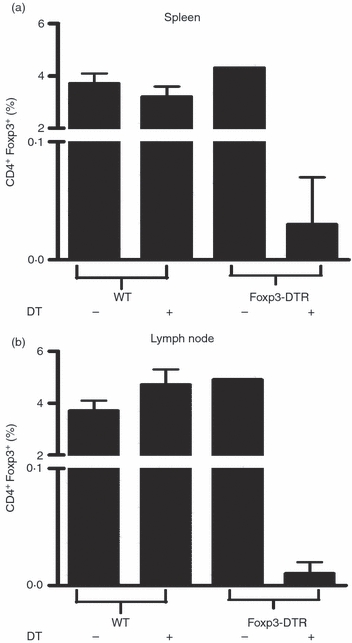

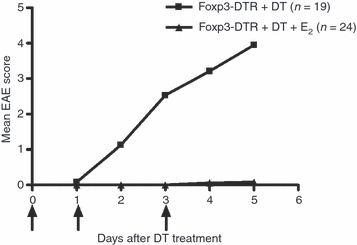

Wild-type C57BL/6 and Foxp3-DTR mice were immunized with MOG-35-55 peptide in complete Freund's adjuvant and treated with DT or left untreated at onset of clinical signs of EAE. Three treatments with 1 μg DT per day successfully ablated Foxp3 expression in spleen (Fig. 1a) and lymph node (Fig. 1b) of Foxp3-DTR but not wild-type mice and E2 treatment did not reverse this effect (data not shown). As this ablation results in a lethal systemic immune failure, up to 70% mortality was observed following five treatments with DT in unimmunized Foxp3-DTR mice and this rate increased to 88% after seven DT treatments (not shown). Foxp3-DTR mice treated with DT at disease onset developed a typical course of EAE (Fig. 2) with onset of clinical signs on day 11–12 after immunization. However, these mice rapidly developed a moribund condition (complete forelimb and hind limb paralysis); as a result of this paralysis, mice exhibit lack of mobility and are unable to groom themselves and appear wasted. In our studies the disability caused by EAE is distinct but is compounded by the administration of DT leading to the moribund condition resulting from the loss of Foxp3+ Treg cells. The DT-treated mice finally succumb to a terminal autoimmune disease as described by Kim et al.16 In contrast, E2 treatment protected the mice from developing EAE even in the absence of Foxp3+ Treg cells after DT treatment (Fig. 2). The E2-protected Foxp3-DTR mice eventually succumbed to DT-induced mortality after seven treatments with DT (24 days post-immunization) and exhibited a moribund phenotype as described by Kim et al.16

Figure 1.

Diphtheria toxin (DT) treatment effectively depletes Foxp3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells. Wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 and Foxp3-DTR mice were treated with or without 1 μg diphtheria toxin (DT) on days 0, 1 and 3 relative to onset of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE). Spleen (a) and lymph node (b) were harvested on day 5 after DT treatment and Foxp3 expression was measured by flow cytometry using specific antibodies.

Figure 2.

Oestrogen (E2) protects mice from developing experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) in the absence of Foxp3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells. Foxp3-DTR mice were implanted with 2.5 mg 60-day release 17β-oestradiol pellets or placebo pellets 1 week before immunization with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) -35-55 peptide in complete Freund's adjuvant and then injected with 1 μg diphtheria toxin (DT) on days 0, 1 and 3 relative to disease onset. Mice were monitored for EAE. Data represent the mean of four experiments.

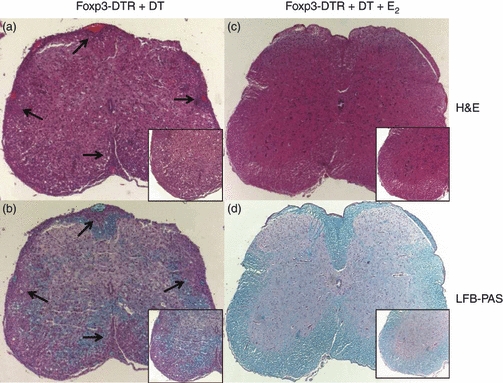

E2 blocks inflammation and demyelination

Because of the high mortality rates among the Foxp3-DTR + DT EAE mice following four or five DT injections, mice were killed after three DT treatments for all ex vivo assays. To assess the extent of inflammation and demyelination in the central nervous system of placebo Foxp3-DTR + DT and Foxp3-DTR + DT + E2 mice, spinal cord sections were stained with haematoxylin & eosin and luxol fast blue-periodic acid Schiff. Spinal cords from DT-treated Foxp3-DTR mice showed massive leucocyte infiltration with several foci of inflammation (as indicated by arrows, Fig. 3a) along with severe demyelination (Fig. 3b). Spinal cords sections from E2-implanted and DT-treated Foxp3-DTR mice looked healthy with no obvious signs of inflammation or demyelination (Fig. 3c,d). These results were identical to previous studies in which inflammation was observed in wild-type mice given placebo but not in E2-treated wild-type mice with EAE.5

Figure 3.

Histopathological evaluation of spinal cords from placebo Foxp3-DTR + diphtheria toxin (DT) (a,b) and oestrogen (E2)-treated (c,d) Foxp3-DTR + DT mice. Spinal cords (shown at a 10 × magnification) from Foxp3-DTR + DT mice exhibit massive leucocyte infiltration (a) as shown by haematoxylin & eosin staining, whereas E2-treated spinal cords lack infiltrating cells (c). Also, demyelination was prevented in E2-treated Foxp3-DTR mice (d). The inset panels represent the sections at a 20 × magnification. Arrows denote foci of inflammation. Representative images of three experiments are shown.

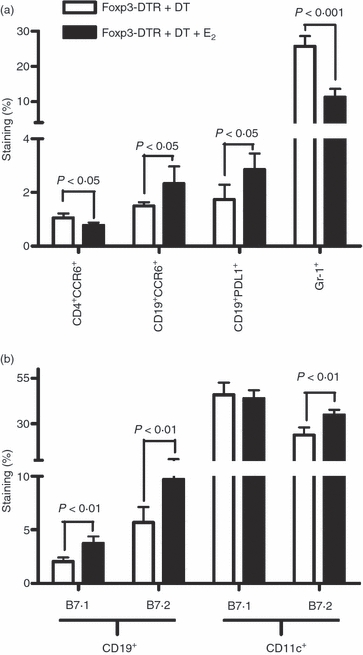

PD-L1 and CCR6 are up-regulated on B cells following E2 treatment

The lack of development of clinical and histological EAE in the E2-implanted compared with placebo-treated Foxp3-DTR + DT mice strongly suggests alternative pathways that can compensate for the lack of Treg cells. One such pathway might involve PD-1/PD-L1 interactions on T cells and antigen-presenting cells that are known to play a key role in suppressing T-cell responses.17 As shown in Fig. 4(a), both PD-L1 and CCR6 were strongly up-regulated on CD19+ B cells from E2-treated Foxp3-DTR + DT mice, whereas expression of CCR6 on CD4+ T cells was significantly reduced. In addition, activation markers B7.1 and B7.2 were significantly increased on B cells in the E2-treated mice (Fig. 4b). Expression of B7.2 but not B7.1 was also elevated on CD11c+ dendritic cells following E2 treatment. Granulocytes were also reduced in mice protected with E2.

Figure 4.

Expression of programmed death 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1), CCR6 and activation markers on splenic B cells. Foxp3-DTR mice were administered three doses of diphtheria toxin (DT) and splenocytes from placebo and oestrogen (E2) -treated mice were analysed by flow cytometry on day 4–5 for expression of (a) PD-L1, CCR6, Gr-1 and (b) B7.1 (CD80) and B7.2 (CD86) on specific cell types. Cells were gated on CD19 and CD11c to determine expression of B7.1 and B7.2. One representative experiment of four is shown with a total of 10 placebo-treated and E2-implanted Foxp3-DTR mice.

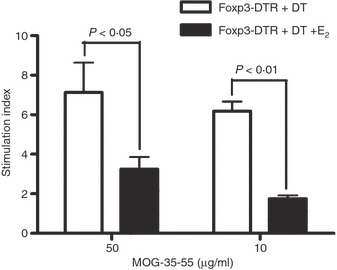

E2 treatment suppresses T-cell proliferation

To determine if the up-regulation of PD-L1 and activation markers would translate to functional changes in T-cell proliferation, splenocytes from Foxp3-DTR + DT and E2-treated Foxp3-DTR + DT mice were cultured in the presence of antigen and their proliferation was measured using a radioactivity-based assay. The results clearly demonstrated that cells from E2-implanted mice had a two- to threefold lower proliferative capability (P < 0·05) compared with placebo-treated Foxp3-DTR + DT mice (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Oestrogen (E2) treatment of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) significantly inhibits proliferation of spleen cells. Spleens were collected from Foxp3-DTR mice with EAE treated or not with 2.5 mg E2. Cells were plated on a 96-well microtitre plate and cultured with 10 or 50 μg/ml of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) -35-55 peptide for 72 hr, the last 18 hr in the presence of [3H]-thymidine. Stimulation indices were determined by calculating the ratio of antigen-specific counts/min to medium alone counts/min. Foxp3-DTR group without and with E2 implants showed a background of 600 and 1000 counts/min, respectively. Representative data from a total of three experiments are shown.

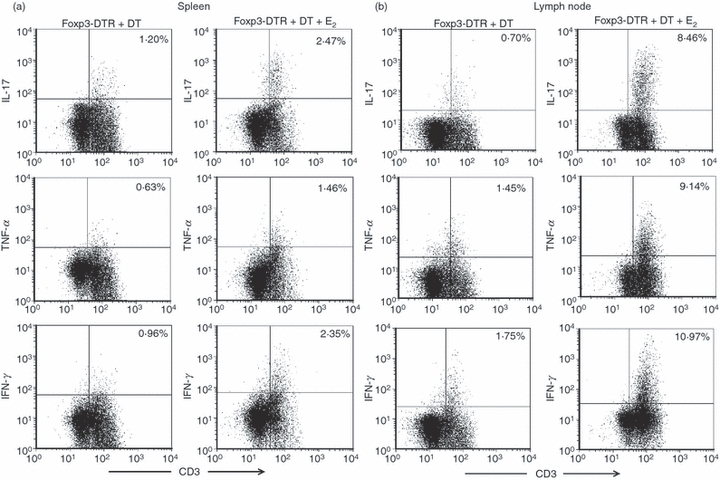

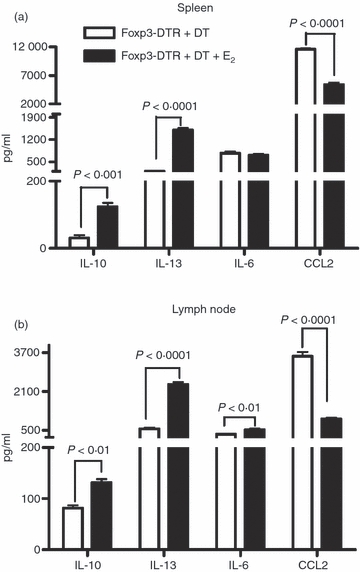

Levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines are decreased in brain, but both T helper type 1 and type 2 cytokines are elevated in peripheral immune organs in E2-protected Foxp3-DTR mice

Some studies employing agents that resolve clinical signs of EAE and associated inflammation demonstrate a reduction in the secretion of pro-inflammatory T helper type 1 and type 17 cytokines.18 We therefore anticipated that there might be similar reductions in inflammatory cytokines as a result of E2-mediated protection. Intracellular staining for IL-17, TNF-α and IFN-γ was performed on spleen and lymph node cells from Foxp3-DTR + DT and E2-implanted Foxp3-DTR + DT mice. Surprisingly, levels of all three inflammatory cytokines were elevated in spleens (Fig. 6a) and lymph nodes (Fig. 6b) from E2-treated Foxp3-DTR + DT mice with especially robust production in lymph nodes. In contrast, T cells from brains of E2-implanted Foxp3-DTR mice showed markedly reduced levels of all three inflammatory cytokines (data not shown), reflecting the absence of inflammation in brain tissue. Interestingly, secreted levels of IL-10 and IL-13 were increased significantly in both spleen (Fig. 7a) and lymph node (Fig. 7b). Another marked change was in CCL2 production, which was strongly decreased in spleen and lymph node of E2-protected Foxp3-DTR + DT mice. Treatment with E2 did not alter IL-6 secretion in spleens but slightly increased IL-6 levels in lymph nodes.

Figure 6.

T helper type 1 and type 17 intracellular cytokine levels are elevated in spleen and lymph nodes after oestrogen (E2) treatment. At the end of three diphtheria toxin (DT) treatments, (a) spleen and (b) lymph node cells from placebo and E2-treated Foxp3-DTR mice were cultured in the presence of a leucocyte activation cocktail and then stained for intracellular accumulation of interleukin-17 (IL-17), tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) on T cells. Data shown include cells pooled from a total of three placebo and three E2-treated Foxp3-DTR mice and experiments were repeated twice.

Figure 7.

Splenocytes (a) and lymph node cells (b) from placebo-treated and oestrogen (E2) -treated Foxp3-DTR + DT mice were cultured in the presence of 25 μg/ml myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG)-35-55 peptide for 48 hr. Culture supernatants were assayed for secreted levels of cytokines by the Luminex bead array. One representative experiment of three separate experiments is shown.

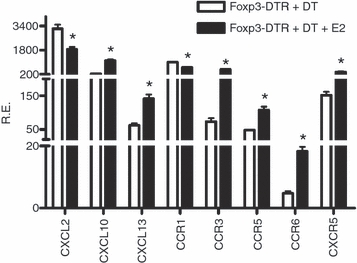

Chemokine and chemokine receptor expression patterns in splenocytes

Chemokines and their receptors play a specialized role in the trafficking of leucocytes under inflammatory conditions. CCL2 is associated with neutrophil recruitment.19 Other chemokines, such as CCL2, CCL5 and CXCL10, influence T-cell and macrophage migration through specific chemokine receptors.20 To understand the expression of these chemokines and their receptors in E2-mediated protection of EAE, mRNA expression of CCL2, CXCL10 and chemokine receptors in spleen were analysed using real-time PCR. The results presented in Fig. 8 show that expression of CXCL2 and CCR1 was significantly reduced whereas expression of CXCL10, CCR3, CCR5 and CCR6 was increased in the E2-treated versus placebo-treated Foxp3-DTR + DT mice. CCL2 mRNA expression was decreased in E2-treated Foxp3-DTR + DT mice (consistent with reduced secretion of CCL2 shown in Fig. 7), although expression of its receptor, CCR2, was not altered (data not shown). In addition, expression of B-cell-associated chemokine, CXCL13, and its receptor, CXCR5 were up-regulated in spleens of E2-treated mice (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Messenger RNA expression of chemokines and chemokine receptors in spleens of oestrogen (E2)-treated Foxp3-DTR mice. Spleen cells from placebo treated Foxp3-DTR + diphtheria toxin (DT) and E2-treated Foxp3-DTR + DT mice were harvested at the end of three DT treatments, mRNA was synthesized and real-time PCR performed using Universal Taqman master mix and specific primers. One representative experiment of three separate experiments is shown. *P < 0.01.

Discussion

Our previous data indicated that E2-induced protection against EAE involved expansion of Foxp3 Treg cells7 and potentiation of Treg-cell suppressive activity by up-regulation of PD-1.13–15 Additionally, E2 treatment enhanced the suppressive activity of antigen-presenting cells, particularly dendritic cells, on pathogenic T cells.13 The availability of the Foxp3-DTR mouse strain has allowed us for the first time to determine if Treg cells constitute the major non-redundant protective pathway of E2-mediated protection against EAE. The results of this study clearly demonstrate: (i) that E2 can still fully protect mice from clinical and histological signs of EAE in the absence of Foxp3+ cells, indicating that Treg cells are not the sole E2-induced EAE-protective mechanism. This finding implicates alternative E2-dependent EAE-protective pathways that could compensate for the lack of Treg cells. (ii) Treatment with E2 inhibited proliferation and expression of CCL2 and CXCL2, but enhanced secretion of IL-10 and IL-13 by MOG-35-55-specific spleen cells. (iii) These changes occurred concomitantly with increased expression of several chemokines and receptors, including CXCL13 and CXCR5, and the negative co-activation molecules, PD-L1 and B7.2, by MOG-activated B cells. (iv) Treatment with E2 resulted in higher percentages of spleen and lymph node T cells expressing IL-17, IFN-γ and TNF-α, but with lower expression of CCR6, suggesting sequestration of MOG-35-55 peptide-specific T cells in peripheral immune organs. These results strongly suggest that E2-induced mechanisms that provide protection against EAE in the absence of Treg cells include induction of regulatory B cells and peripheral sequestration of encephalitogenic T cells.

The role of B cells as a regulator of inflammation in EAE, collagen-induced arthritis and airway allergy has been recognized relatively recently by several groups.21,22 Regulatory B cells are known to secrete high levels of IL-10, reportedly induced by B-cell-activating factor and exhibit a distinct CD1dhi CD5+ phenotype derived mainly from marginal zone B cells.23,24 Of interest to our study, regulatory B cells have been shown to facilitate the recruitment of FoxP3+ Treg cells into inflamed tissue concomitant with recovery from EAE25 and reduced airway inflammation,23 possibly implicating Treg cells in the suppressive pathway. Our result suggesting a role for regulatory B cells in E2-induced protection against EAE in the absence of Treg cells is further supported by the lack of E2-mediated protection in B-cell knockout mice (manuscript in preparation).

Other implicated regulatory pathways for EAE involve co-activation molecules such as PD-1 together with its ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L217,26 and CD28/CTLA-4 together with their ligands, B7.1 (CD80) and B7.2 (CD86). Our recent studies have shown that PD-1 is required for E2-mediated protection of EAE,13–15 and others have shown that PD-L1 plays a more significant role than PD-L2 in PD-1-mediated inhibition of disease.27 Expression of the co-stimulatory molecule, B7.2 is increased on both B cells and dendritic cells in E2-protected mice. B7.1 and B7.2 are important co-stimulatory molecules that engage with their common ligand, CD28, on T cells and deliver either a positive or negative signal to the T cell. However, B7.2 expression is thought to be more critical in tolerance induction28 mediated by PD-1/PD-L1 interactions by interfering with T-cell receptor signalling.29 Also, in the absence of this co-stimulation, the pathogenic T cells are unable to sustain themselves, leading to a milder disease in mice.30

Unexpectedly, we observed elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines in the periphery of E2-protected Foxp3-DTR mice lacking Treg cells. We speculate that one of the mechanisms by which E2 exerts its protective effect is via sequestration of the pathogenic cells away from the target organ. Similar pathways have been described following Natalizumab treatment in patients with multiple sclerosis.31 The E2-protected mice also exhibited enhanced splenic expression of the chemokine, CXCL13, and its receptor, CXCR5. CXCL13 is a chemokine produced by cells of the myeloid lineage32,33 and is important for the migration of B cells to spleen and other lymphoid organs.34 CXCL13 is detected in spinal cords of diseased mice35 and its expression is suppressed in patients following Natalizumab therapy.36 In addition, CXCR5+ dendritic cells alter antigen-specific T-cell responses.37

In summary, our results demonstrate conclusively that E2 can induce highly potent protection against clinical and histological signs of EAE in the absence of Foxp3+ Treg cells, clearly implicating other compensatory regulatory mechanisms that probably include regulatory B cells.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr Sushmita Sinha for helpful discussions and Ms Eva Niehaus for assistance with manuscript preparation. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants NS45445 and NS49210; National Multiple Sclerosis Society grant RG3405-C-6; and the Biomedical Laboratory R&D Service, Department of Veterans’ Affairs. Dr Melissa Yates is a Postdoctoral Fellow of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society and this work was supported in part by the National Multiple Sclerosis Society Postdoctoral Fellowship FG1832-A-1.

Acknowledgments

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to declare regarding this article.

References

- 1.Offner H, Polanczyk M. A potential role for estrogen in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and multiple sclerosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1089:343–72. doi: 10.1196/annals.1386.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jansson L, Holmdahl R. Estrogen-mediated immunosuppression in autoimmune diseases. Inflamm Res. 1998;47:290–301. doi: 10.1007/s000110050332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zandman-Goddard G, Peeva E, Shoenfeld Y. Gender and autoimmunity. Autoimmun Rev. 2007;6:366–72. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vukusic S, Hutchinson M, Hours M, Moreau T, Cortinovis-Tourniaire P, Adeleine P, Confavreux C. The Pregnancy In Multiple Sclerosis G. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis (the PRIMS study): clinical predictors of post-partum relapse. Brain. 2004;127(Pt 6):1353–60. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bebo BF, Jr, Fyfe-Johnson A, Adlard K, Beam AG, Vandenbark AA, Offner H. Low-dose estrogen therapy ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in two different inbred mouse strains. J Immunol. 2001;166:2080–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jansson L, Olsson T, Holmdahl R. Estrogen induces a potent suppression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and collagen-induced arthritis in mice. J Neuroimmunol. 1994;53:203–7. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(94)90030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polanczyk M, Yellayi S, Zamora A, et al. Estrogen receptor-1 (Esr1) and -2 (Esr2) regulate the severity of clinical experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in male mice. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:1915–24. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63752-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dulos J, Vijn P, van Doorn C, Hofstra CL, Veening-Griffioen D, de Graaf J, Dijcks FA, Boots AM. Suppression of the inflammatory response in experimental arthritis is mediated via estrogen receptor alpha but not estrogen receptor beta. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R101. doi: 10.1186/ar3032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou X, Bailey-Bucktrout S, Jeker LT, Bluestone JA. Plasticity of CD4+ FoxP3+ T cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:281–5. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esensten JH, Wofsy D, Bluestone JA. Regulatory T cells as therapeutic targets in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2009;5:560–5. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2009.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akirav EM, Bergman CM, Hill M, Ruddle NH. Depletion of CD4+ CD25+ T cells exacerbates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis induced by mouse, but not rat, antigens. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:3511–9. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou X, Bailey-Bucktrout SL, Jeker LT, et al. Instability of the transcription factor Foxp3 leads to the generation of pathogenic memory T cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1000–7. doi: 10.1038/ni.1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polanczyk MJ, Carson BD, Subramanian S, Afentoulis M, Vandenbark AA, Ziegler SF, Offner H. Cutting edge: estrogen drives expansion of the CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cell compartment. J Immunol. 2004;173:2227–30. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.4.2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polanczyk MJ, Hopke C, Vandenbark AA, Offner H. Treg suppressive activity involves estrogen-dependent expression of programmed death-1 (PD-1) Int Immunol. 2007;19:337–43. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang C, Dehghani B, Li Y, Kaler LJ, Vandenbark AA, Offner H. Oestrogen modulates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and interleukin-17 production via programmed death 1. Immunology. 2009;126:329–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.03051.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim JM, Rasmussen JP, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells prevent catastrophic autoimmunity throughout the lifespan of mice. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:191–7. doi: 10.1038/ni1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Latchman YE, Liang SC, Wu Y, et al. PD-L1-deficient mice show that PD-L1 on T cells, antigen-presenting cells, and host tissues negatively regulates T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10691–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307252101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanakasabai S, Chearwae W, Walline CC, Iams W, Adams SM, Bright JJ. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta agonists inhibit T helper type 1 (Th1) and Th17 responses in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Immunology. 2010;130:572–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armstrong DA, Major JA, Chudyk A, Hamilton TA. Neutrophil chemoattractant genes KC and MIP-2 are expressed in different cell populations at sites of surgical injury. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:641–8. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0803370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Omari KM, Lutz SE, Santambrogio L, Lira SA, Raine CS. Neuroprotection and remyelination after autoimmune demyelination in mice that inducibly overexpress CXCL1. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:164–76. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kala M, Rhodes SN, Piao WH, Shi FD, Campagnolo DI, Vollmer TL. B cells from glatiramer acetate-treated mice suppress experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Exp Neurol. 2010;221:136–45. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fillatreau S, Sweenie CH, McGeachy MJ, Gray D, Anderton SM. B cells regulate autoimmunity by provision of IL-10. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:944–50. doi: 10.1038/ni833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amu S, Saunders SP, Kronenberg M, Mangan NE, Atzberger A, Fallon PG. Regulatory B cells prevent and reverse allergic airway inflammation via FoxP3-positive T regulatory cells in a murine model. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:1114–24e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang M, Sun L, Wang S, Ko KH, Xu H, Zheng BJ, Cao X, Lu L. Novel function of B cell-activating factor in the induction of IL-10-producing regulatory B cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:3321–5. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mann MK, Maresz K, Shriver LP, Tan Y, Dittel BN. B cell regulation of CD4+ CD25+ T regulatory cells and IL-10 via B7 is essential for recovery from experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2007;178:3447–56. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blank C, Mackensen A. Contribution of the PD-L1/PD-1 pathway to T-cell exhaustion: an update on implications for chronic infections and tumor evasion. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2007;56:739–45. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0272-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carter LL, Leach MW, Azoitei ML, et al. PD-1/PD-L1, but not PD-1/PD-L2, interactions regulate the severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol. 2007;182:124–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu L, Kuchroo VK, Weiner HL. B7.2 (CD86) but not B7.1 (CD80) costimulation is required for the induction of low dose oral tolerance. J Immunol. 1999;163:2284–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fife BT, Pauken KE, Eagar TN, et al. Interactions between PD-1 and PD-L1 promote tolerance by blocking the TCR-induced stop signal. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1185–92. doi: 10.1038/ni.1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang TT, Sobel RA, Wei T, Ransohoff RM, Kuchroo VK, Sharpe AH. Recovery from EAE is associated with decreased survival of encephalitogenic T cells in the CNS of B7-1/B7-2-deficient mice. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:2022–32. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kivisakk P, Healy BC, Viglietta V, Quintana FJ, Hootstein MA, Weiner HL, Khoury SJ. Natalizumab treatment is associated with peripheral sequestration of proinflammatory T cells. Neurology. 2009;72:1922–30. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a8266f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carlsen HS, Baekkevold ES, Morton HC, Haraldsen G, Brandtzaeg P. Monocyte-like and mature macrophages produce CXCL13 (B cell-attracting chemokine 1) in inflammatory lesions with lymphoid neogenesis. Blood. 2004;104:3021–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McDonald KG, McDonough JS, Dieckgraefe BK, Newberry RD. Dendritic cells produce CXCL13 and participate in the development of murine small intestine lymphoid tissues. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:2367–77. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forster R, Mattis AE, Kremmer E, Wolf E, Brem G, Lipp M. A putative chemokine receptor, BLR1, directs B cell migration to defined lymphoid organs and specific anatomic compartments of the spleen. Cell. 1996;87:1037–47. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81798-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bagaeva LV, Rao P, Powers JM, Segal BM. CXC chemokine ligand 13 plays a role in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2006;176:7676–85. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sellebjerg F, Bornsen L, Khademi M, Krakauer M, Olsson T, Frederiksen JL, Sorensen PS. Increased cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of the chemokine CXCL13 in active MS. Neurology. 2009;73:2003–10. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c5b457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu MT, Hwang ST. CXCR5-transduced bone marrow-derived dendritic cells traffic to B cell zones of lymph nodes and modify antigen-specific immune responses. J Immunol. 2002;168:5096–102. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.5096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]