Abstract

Airway remodelling contributes to increased morbidity and mortality in asthma. We have reported that triptolide, the major component responsible for the immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory effects of Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F, inhibited pulmonary inflammation in patients with steroid-resistant asthma. In the present study, we investigated whether triptolide inhibits airway remodelling in a mouse asthma model and observed the effects of triptolide on the transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1)/Smad pathway in ovalbumin (OVA) -sensitized mice. BALB/c mice were sensitized to intraperitoneal OVA followed by repetitive OVA challenge for 8 weeks. Treatments included triptolide (40 μg/kg) and dexamethasone (2 mg/kg). The area of bronchial airway (WAt/basement membrane perimeter) and smooth muscle (WAm/basement membrane perimeter), mucus index and collagen area were assessed 24 hr after the final OVA challenge. Levels of TGF-β1 were assessed by immunohistology and ELISA, levels of TGF-β1 mRNA were measured by RT-PCR, and levels of pSmad2/3 and Smad7 were assessed by Western blot. Triptolide and dexamethasone significantly reduced allergen-induced increases in the thickness of bronchial airway and smooth muscle, mucous gland hypertrophy, goblet cell hyperplasia and collagen deposition. Levels of lung TGF-β1, TGF-β1 mRNA and pSmad2/3 were significantly reduced in mice treated with triptolide and dexamethasone, and this was associated with a significant increase in levels of Smad7. Triptolide may function as an inhibitor of asthma airway remodelling. It may be a potential drug for the treatment of patients with a severe asthma airway.

Keywords: airway remodelling, asthma, mice, transforming growth factor-β1/Smad signalling pathway, triptolide

Introduction

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways in which many cells and cellular elements play a role. The morbidity and mortality of asthma have increased sharply worldwide and it has become a severe global public health problem.1 The frequent occurrence of injury and repair initiated by chronic inflammation could lead to structura1 changes in the airway, collectively termed airway remodelling. Airway remodelling is characterized by airway wall thickening, subepithelial fibrosis, increased smooth muscle mass, angiogenesis and increased mucous glands.2,3 Generally, airway remodelling is thought to contribute to airway hyper-responsiveness and irreversible airflow limitation.

Severe asthma has a distinct pathophysiology including airway remodelling that contributes to the decreased effectiveness of standard therapy. The treatment strategy for asthma airway remodelling consists mainly of the use of bronchodilators (such as β-agonists, theophylline, anti-cholinergics and anti-leukotrienes). Previous studies have reported that dexamethasone (corticosteroid) treatment during the allergen challenge period inhibits airway remodelling and inflammation in the lungs of mouse asthma models.4,5 However, approximately 5% of patients do not respond to this therapy. For these reasons, effective therapies that are targeted at severe asthma and that can inhibit asthma airway remodelling are needed.6–8

Triptolide, a diterpenoid triepoxide, is the major component purified from a Chinese herb Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F (TWHF) and is responsible for the immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory effects of TWHF. Triptolide has the effects of inhibiting proliferation and inducing apoptosis.9–11 Clinical and basic studies have been performed to investigate the usefulness of triptolide in the treatment of asthma.12–14 We previously showed that triptolide inhibited pulmonary inflammation in patients with steroid-resistant asthma and some studies indicate that triptolide can relieve pulmonary pathology and control the progress of asthma airway remodelling.15 However, the mechanism of triptolide's role in airway remodelling remains unknown.

Transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) is a pro-fibrotic cytokine thought to play an important role in promoting the structural changes of airway remodelling in asthma. Hallmarks of the TGF-β1 signalling transduction pathways include the activation of TGF-β1 type I and II receptors and the subsequent phosphorylation and translocation of the intracellular effectors Smad2 and Smad3 to the nucleus where they regulate gene transcription. Smad7 is an intracellular inhibitor, which is rapidly induced by TGF-β family members and provides a negative feedback loop. Recent studies on a mouse model of allergic asthma have demonstrated in situ activation of these TGF-β1 signalling pathways.16–19 Therefore, it seems reasonable to hypothesize that targeting the TGF-β1/Smad signalling pathway, by macromolecules or small molecules, may provide a novel therapeutic method for asthma airway remodelling.

Materials and methods

Animals

BALB/c mice (females) were obtained and maintained in a pathogen-free environment in the facility of the Centre of Animal Experiments of Sun Yat-sen University (Certificate of Conformity: Guangdong Experimental Animal Testing by certificate No. 2006A059). The mice were housed in a temperature controlled room with 12-hr dark : light cycles, and allowed food and water ad libitum. All the experiments described below were performed in accordance with the regulations of the Centre of Animal Experiments of Sun Yat-sen University.

Reagents

The following drugs and chemicals were purchased commercially and used: chicken egg ovalbumin (OVA) (grade V, A5503; Sigma, St.louis, MO, USA); aluminium hydroxide (Guangzhou Chemical Reagent Factory, China); crystalline triptolide (PG490, molecular weight 360, purity 99%) from the Institute of Dermatology, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Nanjing, China). Triptolide was dissolved in DMSO and the stock solutions (1 mg/ml) were stored at −20°. Triptolide was freshly diluted to the indicated concentration with culture medium before use in experiments. The test conditions of DMSO concentration did not exceed 0·001% (weight/volume). Polyclonal TGF-β1 rat anti-mouse antibodies (Abcam co., Cambridge, UK); streptavidin–biotin–peroxidase complex immunohistochemical detection kit (Fujian Maixing Biotechnology co., Fuzhou, Fujian, China); Trizol (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA); PCR kit (Promega, Fitchburg, WI, USA); reverse transcriptase kit (Fermentas Inc., Vilnius, Lithuania); anti-phospho-Smad2/3 and Smad7 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); antibodies against β-actin (1 : 1000; Thermo Scientific IHC, Fremont, CA), tubulin (1 : 5000; Sigma); and TGF-β1 ELISA-kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) were obtained.

Sensitization and antigen challenge

Forty female BABL/c mice were randomly divided into four groups with 10 mice in each group, and treated as follows. (i) In the Control group mice were treated with saline. (ii) In the OVA-sensitized/challenged group (OVA group) mice were sensitized and challenged with OVA. They were sensitized on days 0 and 14 by intraperitoneal injection of 10 μg OVA emulsified in 1 mg of aluminium hydroxide in a total volume of 200 μl. Seven days after the last sensitization, mice were exposed to OVA aerosol (2·5% weight/volume diluted in sterile physiological saline) for up to 30 min three times per week for 8 weeks. The aerosol (particle size 2·0–6·0 μm) was generated by a nebulizer (Ultrasonic nebulizer boy037G6000, Pari, Germany) driven by filling a perspex cylinder chamber (diameter 50 cm, height 50 cm) with a nebulized solution.20 (iii) The triptolide-treated group (TRP group) comprised mice that were sensitized and challenged as in the asthmatic group described above, and treated with 40 μg/kg triptolide by intraperitoneal injection before challenge.12,13 (iv) In the dexamethasone-treated group (DEX group) mice were sensitized and challenged as above, and were given 2 mg/kg dexamethasone by intraperitoneal injection before challenge.4,5

Measurement of TGF-β1 level in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

At 24 hr after the last challenge, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) was obtained from the mice under anaesthesia using 1 ml sterile isotonic saline. Lavage was performed four times in each mouse and the total volume was collected separately. The volume of fluid collected in each mouse ranged from 3·0 to 3·5 ml. The lavage fluid was centrifuged at 1668.75 g at 4° for 15 min. The TGF-β1 concentrations in the BALF were measured with an ELISA-kit (R&D Systems). The protocol followed the manufacturer's instructions.

Lung histology

Lungs were removed from the mice after killing 24 hr after the last challenge. The tissues from the left lung were fixed with 10% neutral buffered formalin. The specimens were dehydrated and embedded in paraffin. For histological examination, 5-μm sections of fixed embedded tissues were cut on a rotary microtome, placed on glass slides, deparaffinized, and stained sequentially with haematoxylin & eosin to assess the airway remodelling. Mucus production was assessed from lung sections stained with periodic acid Schiff (PAS). Masson's trichrome (MT) was used to determine collagen deposition in the lung.

Morphometric analysis

The histological analyses were performed by observers who were not aware of the groups of mice from which the samples originated. Images were captured with a digital camera. At least 10 bronchioles with 150–200 μm inner diameter were selected and counted in each slide. For the thickness of tracheal basement membrane, three measures were taken, and the average basement membrane thickness was calculated. The area of airway wall (WAt) and area of smooth muscle (WAm) were determined by morphometric analysis (image-pro plus 6.0; MediaCybernetics Co., Bethesda, MD, USA) on transverse sections after haematoxylin & eosin staining. Basement membrane perimeter (Pbm) was measured for normalization of WAt and WAm. Then we used the ratios of WAt to Pbm (WAt/Pbm) and WAm to Pbm (WAm/Pbm) to evaluate airway remodelling.

Mucus production was determined on transverse sections from the upper left lobe of the lung. The mucus index was calculated as follows: the percentage of the area of mucus on the epithelial surface stained with PAS was determined by image-pro plus 6.0. The area of the respiratory epithelium was outlined, and the image analyser quantified the area of PAS-stained mucus within this reference area. At least 10 bronchioles were counted in each slide. Results were expressed as the percentage of PAS-positive cells/bronchiole, which is calculated from the area of PAS-positive epithelial cells per bronchus divided by the total number of epithelial cells of each bronchiole.

Staining with MT was used to determine collagen deposition in the lung. The image-pro plus 6.0 allowed for manual outlining of the trichrome-stained collagen layer and computed the area within the outlined ring of tissue. Briefly, two to four specimens of the MT-stained histological preparations of the lung lobe, in which the total length of the epithelial basement membrane of the bronchioles was 1·0–2·5 mm, were selected and the fibrotic area (stained in blue) beneath the basement membrane in 20 μm depth was measured. The mean score of the fibrotic area divided by the basement membrane perimeter in two to four preparations of one mouse were calculated, then the mean values of subepithelial fibrosis were calculated in 10 mice.21–23

Analysis of TGF-β1 mRNA expression

Total RNA was isolated from the right lung tissue using TRIzol Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. One millilitre of trizol reagent was added to frozen airway samples and the resulting preparation was ground using a mortar and pestle for 5 min. Chloroform (200 μl) was added and the solution was centrifuged (6750 g, 4°) for 20 min. The aqueous layer was removed by aspiration with a pipette, and an equal volume of isopropanol was added to the aqueous layer. After centrifugation for 17 min as above, the supernatant was discarded and the remaining pellet was washed in 75% ethanol and suspended in 20 μl DNase-free and RNase-free water. The purity and concentration of each RNA sample was measured and analysed spectroscopically using UV absorbance at 260 and 280 nm. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed with the Moloney murine leukaemia virus reverse transcriptase (Promega). The cDNA was amplified with the following primers (sense and anti-sense, respectively): β-actin (5′-CAGAAGGACTCCTACGTG-3′, 5′-GCTCGTCAGGATCTTCATG-3′, 440 bp), TGF-β1 (5′-ACCTGCAAGACCATCGACAT-3′, 5′-GGTTTTCTCATAGATGGCGT-3′, 279 bp); PCR conditions were initial denaturation at 94° for 3 min then denaturation at 94° for 30 seconds, primer annealing at 60° for 30 seconds, and extension at 72° for 1 min for 35 cycles, followed by a final extension at 72° for 10 min. The PCR were size fractionated by electrophoresis on 1·5% agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide stain under UV light. The intensity of each band was analysed by densitometry using Scion Image software (Scion Corporation, Fredericle, MD, USA) and the relative mRNA expression of the target gene was normalized to the β-actin control.

Analysis of TGF-β1 expression

Expression of TGF-β1 was assessed by semi-quantitative immunohistochemistry. After being deparaffinized, the section was incubated in 0·01 mol/l citric acid buffer (pH 6·0) for 15 min of microwave antigen retrieval. After cooling, the section was incubated in 3 g/l H2O2 for 30 min (37°), to inactivate the endogenous peroxidase. After blocking by 1 : 10 normal horse serum for 30 min (37°), the supernatant was discarded. Primary anti-mouse TGF-β1 (1 : 400 dilution) was added overnight at 4°. Then, biotinylated goat anti-rat secondary antibody and streptavidin–horseradish peroxidase were added to the slides and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Staining was completed by incubation with diaminobenzidine chromogen solution at room temperature. Positive cells were stained brown and positive signals were the cytoplasm/nucleus brown-stained particles. We used image-pro plus 6.0 to measure TGF-β1 expression intensity. The corrected average optical density was calculated as follows: integrated optical density (IOD SUM) divided by the area of the selected region (area SUM).

Westen blot

Total protein was isolated from the right lung by homogenization in a buffer containing 50 mm HEPES (pH 7·4), 1% Nonidet P-40, 0·5% deoxycholate, 5 mm EDTA, 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, 5 mm sodium fluoride, and phosphatase and protease inhibitor cocktails (Sigma-Aldrich). The lysates were centrifuged at 15 545 g for 15 min at 4°, the supernatants were collected, their total protein content was determined using a conventional method, and aliquots were stored at −70° until assayed. Equal amounts of sample proteins were resolved by 10% SDS–PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane by electroblotting in a buffer containing Tris–HCl (25 mm), glycine (192 mm), and methanol (20%, volume/volume). After transfer, the blots were incubated in 5% powdered milk in Tween/Tris-buffered saline [10 mm Tris–HCl (pH 7·5), 0·15 m NaCl and 0·1% Tween-20] at room temperature for 1 hr, then incubated with anti-pSmad3 and Smad7 antibodies overnight at 4°, washed with Tween/Tris-buffered saline, and exposed to corresponding horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgG for 1 hr. The labelled band was detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit and developed with Hyperfilm-enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ).

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were performed using one-way analysis of variance followed by the Fisher's test. Significant differences between groups were determined using the unpaired Student's t-test. Values of P < 0·05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

We have developed a mouse model of airway remodelling through repetitive OVA challenge. Mice were subjected to OVA challenge three times a week for 8 weeks and developed significant eosinophilic inflammation and airway remodelling similar to that observed in human chronic asthma.

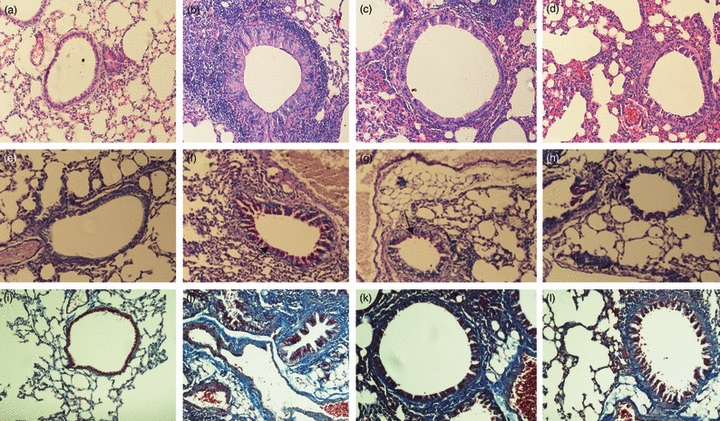

Effect of triptolide on airway remodelling

In this study, we used the ratios WAt/Pbm and WAm/Pbm to evaluate airway remodelling. Image analysis revealed that, for WAt/Pbm: the 8-week OVA-challenged mice (OVA group) presented thicker airway walls (17·9 ± 1·2 versus 10·8 ± 1·2 μm2/μm, Fig. 1a,b, Table 1, P < 0·01) than the Control group after correction for airway basement perimeter. Triptolide and dexamethasone were equally effective in reducing airway wall thickening (12·6 ± 1·2 versus 13·0 ± 1·3 μm2/μm, Fig. 1c,d, Table 1, P > 0·05). There was no significant difference between the TRP and DEX groups. For WAm/Pbm, the OVA group had an increased smooth muscle layer compared with the Control group (6·34 ± 0·66) versus 3·35 ± 0·34 μm2/μm, Fig. 1a,b, Table 1, P < 0·01). Triptolide and dexamethasone were equally effective in reducing myocyte hyperplasia (4·8 ± 0·5 versus 4·9 ± 0·4 μm2/μm, Fig. 1c,d, Table 1, P > 0·05). There was no significant difference between the TRP and DEX groups.

Figure 1.

Effects of triptolide on airway remodelling in asthmatic mice. Representative photomicrographs of (a–d) haematoxylin & eosin staining; (e–h) periodic acid-Schiff staining and (i–l) Masson's trichrome staining of lung sections from the Control group, OVA-challenged mice group (OVA), triptolide-treated group (TRP) and dexamethasone-treated group (DEX) are shown. (a,e,i) Control group; (b,f,j) asthmatic group; (c,g,k) triptolide-treated group; and (d,h,l) dexamethasone-treated group. Note the airway thickening, goblet cell hyperplasia, collagen deposition. Triptolide and dexamethasone reduced both collagen deposition and reticular basement membrane thickening, and inhibited smooth muscle layer thickening, epithelial hyperplasia and airway wall thickening in the mouse model (arrowhead). (a–d, i–l original magnification × 200; e–h original magnification × 400).

Table 1.

Comparison of airway remodelling in the four groups ( )

)

| Group | WAt/Pbm (μm2/μm) | WAm/Pbm (μm2/μm) | Mucous index (%) | Collagen area (μm2/μm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | 10·80 ± 1·20 | 3·35 ± 0·34 | 1·97 ± 0·16 | 4·03 ± 0·73 |

| OVA group | 17·86 ± 1·221 | 6·34 ± 0·661 | 41·70 ± 1·671 | 21·66 ± 3·341 |

| TRP group | 12·61 ± 1·171,2 | 4·83 ± 0·461,2 | 24·08 ± 1·291,2 | 13·61 ± 1·161,2 |

| DEX group | 13·00 ± 1·301,2 | 4·85 ± 0·381,2 | 23·72 ± 1·091,2 | 13·08 ± 0·681,2 |

| F | 60·84 | 66·26 | 1868·03 | 148·83 |

| P | < 0·01 | < 0·01 | < 0·01 | < 0·01 |

P < 0·01 compared with Control group

P < 0·01 compared with OVA group. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 10/group.

OVA, ovalbumin; TRP, triptorelide; DEX, dexamethasone.

Effect of triptolide on mucous gland hypertrophy and goblet cell hyperplasia

Mucus hypersecretion, which is one of the pathological features in asthma and contributes significantly to airflow limitation, is accompanied by mucous gland hypertrophy and goblet cell hyperplasia. Therefore, the mucous index in lung sections was quantified using PAS staining. Goblet cell hyperplasia was observed in the OVA group but not in the Control group (41·70 ± 1·67 versus 1·97 ± 0·16% of airway cells, Fig. 1e,f, Table 1, P < 0·01). Compared with the OVA group, a significant decrease was noticed in airway secretion in the TRP group – the mucous index was 24·08 ± 1·29% (Fig. 1f,g, Table 1, P<0·01, TRP versus OVA), which indicated that triptolide markedly reduced goblet cell hyperplasia in airways. Dexamethasone also reduced airway mucous index compared with the OVA group (23·72 ± 1·09 versus 41·70 ± 1·67%, Fig. 1f,h, Table 1, P < 0·01). There was no significant difference in mucous index between the TRP and DEX groups (24·08 ± 1·29 versus 23·72 ± 1·09%, Fig. 1g,h, Table 1, P>0·05). These data indicated that triptolide and dexamethasone were equally effective in reducing mucous gland hypertrophy and goblet cell hyperplasia (Fig. 1e,h, Table 1).

Effect of triptolide on collagen deposition

Collagen deposition is observed in the airways of patients with asthma, therefore, experiments aimed at quantifying collagen deposition within the murine airway wall were performed. The areas of peribronchial trichrome staining were significantly greater in the OVA group than in the Control group (21·66 ± 3·34 versus 4·03 ± 0·73 μm2/μm, Fig. 1i,j, Table 2, P < 0·01). Administration of triptolide significantly reduced the areas of peribronchial trichrome compared with the OVA group (13·61 ± 1·16 versus 21·66 ± 3·34 μm2/μm, Fig. 1j–k, Table 2, P < 0·01). Dexamethasone also decreased the areas of peribronchial trichrome staining compared with the OVA-sensitized/challenged animals (13·08 ± 0·68 versus 21·66 ± 3·34 μm2/μm, Fig. 1j,l, Table 2, P < 0·01). There was no significant difference in subepithelial fibrosis between the TRP group and DXM group (13·61 ± 1·16 versus 13·08 ± 0·68 μm2/μm, Fig. 1k–l, Table 2, P > 0·05).

Table 2.

Comparison of the transcription of transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) and the expression of TGF-β1 protein in the four groups ( )

)

Effect of triptolide on TGF-β1 mRNA

In view of recent studies showing that triptolide inhibits activation-induced cytokine gene transcription,24 RT-PCR was used to quantify levels of the mRNAs for constituent chains of TGF-β1 in the lungs of mice exposed for 8 weeks to OVA aerosol. Data were normalized to the levels of β-actin mRNA, a prototypical ‘housekeeping gene’, in the same isolated airway preparations. We observed that, after an 8-week OVA-challenge, TGF-β1 mRNA expression in the OVA group was significantly increased compared with the Control group, whereas TGF-β1 mRNA expression in the TRP and DEX groups was significantly decreased compared with that in the OVA group (0·42 ± 0·04 and 0·44 ± 0·04 versus 0·54 ± 0·05, Fig. 2, Table 2, both P < 0·05). There was no significant difference in TGF-β1 mRNA expressions among mice treated with triptolide and dexamethasone (0·42 ± 0·04 versus 0·44 ± 0·04, Fig. 2, Table 2, P > 0·05).

Figure 2.

Effect of triptolide on transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) mRNA. Mice were killed 24 hr after the final ovalbumin (OVA) challenge. Expression of TGF-β1 mRNA in lung tissue was determined by RT-PCR. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 10/group. *P<0.05 in comparison with OVA group; #P<0.05 in comparison with control group. Lane M, 100-bp marker; lane 1, control group; lane 2, OVA group; lane 3, triptolide (TRP) group; lane 4: dexamethasone (DEX) group.

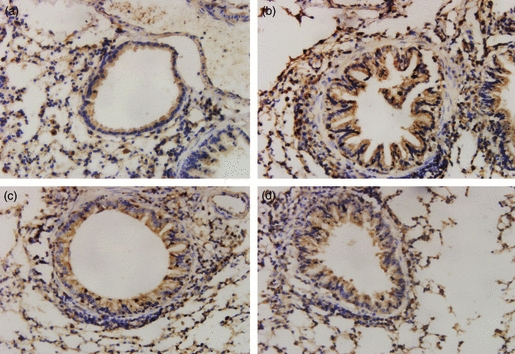

Effect of triptolide on TGF-β1

The immunostaining area of peribronchial TGF-β1 was quantified by image analysis and expressed as corrected average optical density. Positive staining showed TGF-β1 expression in the epithelium, macrophage leucocyte and smooth muscle. The immunostaining areas of peribronchial TGF-β1 in the OVA group was significantly greater than those in the Control group (0·324 ± 0·00795 versus 0·0839 ± 0·00743, Fig. 3a,b, Table 2, P < 0·05). Administration of triptolide and dexamethasone in repetitively OVA-challenged mice both significantly reduced the immunostaining area of TGF-β1 compared with that in the OVA group (0·1152 ± 0·00740 and 0·1141 ± 0·00959 versus 0·324 ± 0·00795, Fig. 3b–d, Table 2, P < 0·05). There was no significant difference of TGF-β1 expression in mice treated with triptolide and dexamethasone.

Figure 3.

Effect of triptolide on expression of transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) protein in the four groups of mouse lung tissue. Expression of TGF-β1 in lung tissue was determined by immunohistochemical staining (streptavidin–peroxidase). Positive staining is depicted in brown. Positive staining showed TGF-β1 expression in the epithelium, macrophage leucocyte and smooth muscle. Administration of triptolide and dexamethasone to mice challenged repetitively with ovalbumin (OVA) significantly reduced the immunostaining area of TGF-β1 compared with the area in untreated mice challenged repetitively with OVA (0.1152 ± 0.00740 and 0.1141 ± 0.00959 versus 0.324 ± 0.00795, P<0.05). Values are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 10/group. (a) Control group, (b) OVA group, (c) triptorelide-treated group, (d) dexamethasone-treated group (× 400).

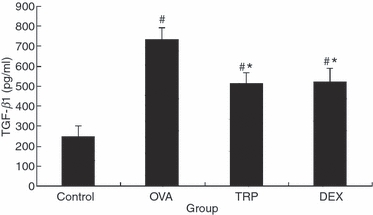

As TGF-β1 is able to induce epithelial hyperplasia, we measured levels of these cytokines in the BALF. Levels of TGF-β1 were significantly increased in the OVA group compared with those in the Control group (734 ± 56 versus 248 ± 53 pg/ml, Fig. 4, P < 0·05). Administration of triptolide significantly reduced levels of BALF TGF-β1 compared with that of the OVA group (512 ± 54 versus 734 ± 56 pg/ml, Fig. 4, P<0·05). Triptolide and dexamethasone were equally effective in reducing levels of BALF TGF-β1 (512 ± 54 versus 524 ± 67 pg/ml, Fig. 4, P > 0·05). There was no significant difference between the TRP and DEX groups.

Figure 4.

Effect of triptolide on transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF). At 24 hr after the last challenge, BALF was obtained from the mice under anaesthesia. Expression of TGF-β1 in BALF was determined by ELISA. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 10/group. *P<0.05 in comparison with OVA group; #P<0.05 in comparison with Control group.

Effect of triptolide on Smad expression

We demonstrated that triptolide inhibited airway remodelling and reduced TGF-β1 expression. Recent reports have demonstrated an improved method for investigating the expression of active TGF-β1 signalling in situ,25 which involves examination of the expression of the intracellular effectors, Smads. Therefore, we investigated the expression patterns of phosphor-Smad2/3 (pSmad2/3) and Smad7 in the lung specimens following administration of dexamethasone to investigate any effect on active TGF-β signalling in airway lesions. Data were normalized to the levels of GAPDH. An increase in expression of pSmad2/3 was observed during prolonged allergen challenge, whereas administration of triptolide and dexamethasone both considerably decreased pSmad2/3 expression (0·73 ± 0·07 versus 0·55 ± 0·04 and 0·51 ± 0·07, Fig. 5, Table 2, P < 0·01). In contrast with pSmad2/3, Smad7 was markedly up-regulated in mice treated with triptolide or dexamethasone compared with the OVA-sensitized/challenged group (0·44 ± 0·03 and 0·44 ± 0·04 versus 0·29 ± 0·06, Fig. 5, Table 2, P < 0·01). There was no significant difference of pSmad2/3 and Smad7 in mice treated with triptolide and dexamethasone (Fig. 5, Table 2, P > 0·05).

Figure 5.

Effect of triptolide on Smad protein. Mice were killed 24 hr after the final ovalbumin (OVA) challenge. Expression of pSmad2/3 and Smad7 in lung tissue was determined by Western blotting. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 10/group. *P<0.05 in comparison with OVA group; #P<0.05 in comparison with Control group.

Discussion

In this study, we established a mouse model of airway remodelling by repetitive OVA-challenge which replicated many of the features of the human disease asthma with a high degree of fidelity. Therefore, we investigated whether administration of triptolide could inhibit the progress of airway remodelling in mice exposed to repetitive allergen challenge, as well as determining whether triptolide could modulate the expression of signalling molecules of the TGF-β1/Smad pathway, which may in turn modulate airway remodelling.

Recent morphological examination of airway tissues with bronchial asthma has revealed that abnormalities in airways, including goblet cell hyperplasia, mucous gland hypertrophy, subepithelial fibrosis and smooth muscle cell hyperplasia or hypertrophy, are in part irreversible.2,3 It is generally accepted that tissue remodelling is a process of wound healing for the maintenance of homeostasis after various injuries. Normally the process means the repair of injured tissues both morphologically and functionally; however, prolonged inflammation may induce remodelling of airways which could differ from wound healing. True to the observed clinical and symptomatic variability, remodelling can be elevated by as much as 50–300% in asthma patients who have died, and from 10 to 100% in subjects who have milder cases.26 Triptolide may offer a much needed therapeutic strategy for asthma airway remodelling.

Our study demonstrated the therapeutic effect of triptolide on airway remodelling in allergic airways disease. Triptolide, a diterpene triepoxide, is a purified compound from Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F and has been identified as one of the major components responsible for the immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory effects of this herb. Triptolide plays a variety of biological activities. It inhibits several pro-inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules that are important mediators of some autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and asthma, and has been shown to be safe and clinically beneficial in these diseases. In addition, triptolide has been reported to inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis of cancer cells in vitro,27,28 and reduce the growth and metastases of tumours in vivo.29–31 It has also been shown to be effective in the treatment of lung fibrosis in animal models.32 In this study, we observed that the triptolide reduced collagen deposition and airway wall thickening involving reticular basement membrane, smooth muscle layer and epithelial hyperplasia, in the mouse model.

Steroids have been administered widely for their anti-proliferative activity in asthma airway remodelling,33 but they are not free of adverse effects. Such adverse reactions may be avoided if triptolide proves effective for the treatment of asthma airway remodelling. The present study indicates that triptolide could be a potential therapeutic agent for asthma by its anti-proliferative and anti-inflammatory properties. Compared with dexamethasone, they have equal ability to prevent asthma airway remodelling in our study. In addition, in our study we found that the mice treated with dexamethasone became thin and irritable, and their fur became dark whereas the mice treated with triptolide had no changes in weight, temperament or colour (data not shown) These findings further encourage the use of this small molecular compound in the treatment of asthma airway remodelling.

How does triptolide inhibit asthma airway remodelling? To use triptolide for clinical development effectively, it is essential to understand its mechanism. We focused on the TGF-β1/Smad signalling pathway. Transforming growth factor β1 is a potent fibrotic factor responsible for the synthesis of extracellular matrix. In recent years, a large number of studies were carried out on the relationship between TGF-β1 and airway remodelling. The studies demonstrated that TGF-β1 is an important cytokine in airway remodelling.17 Members of the TGF-β superfamily through transmembrane Ser-Thr kinase receptors that directly regulate the intracellular Smad pathway. The Smads are a unique family of signal transduction molecules that can transmit signals directly from the cell surface receptors to the nucleus. In our study, we investigated the expression of active TGF-β1 signalling by detecting the expression of the intracellular effectors, Smads. Treatment with triptolide reduced the expression of TGF-β1 and TGF-β1 mRNA and modulated active TGF-β1 signalling in the airways, as demonstrated by a decrease in pSmad2/3 expression concomitant with an increase in the inhibitory molecule, Smad7.

From our study and others, we can deduce that there are several possible mechanisms by which triptolide inhibits airway remodelling in asthma. First, triptolide may inhibit directly airway cell proliferation by anti-proliferative activity against a broad spectrum of mitogens, or by decreasing the transcription and translation of cyclin D1, which consequently arrest the cell cycle progression late in the G1 phase.34 Second, a decrease of the TGF-β1 level is a possible mechanism. We observed a reduction in TGF-β1 expression at both mRNA and protein levels in the lung following triptolide treatment. Finally, triptolide could modulate the activity of the TGF-β1 signalling pathway. In our study, we observed an elevation of Smad7 expression and suppression of pSmad2/3 by triptolide.

Our study indicates that airway remodelling is an irreversible airway hyperplasia process that contributes to airway hyper-responsiveness and irreversible airflow limitation. Treatment with triptolide or dexamethasone could prevent and inhibit the airway remodelling process in allergic airway diseases, but does not tend to reverse the remodelling.

In summary, our study demonstrated that triptolide inhibited asthma airway wall remodelling through mechanisms involving a decrease in the production of TGF-β1 mRNA and TGF-β1 as well as modulation of active TGF-β1 signalling in the lung. This small-molecule natural product may prove to be a candidate for the systemic therapy of asthma airway remodelling. However, additional studies exploring the in vitro biological activity of triptolide are needed to support its use as a potential treatment for asthma airway remodelling.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- BALF

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- DEX

dexamethasone

- HE

haematoxylin & eosin

- IOD

integrated optical density

- MT

Masson's trichrome

- OVA

ovalbumin

- PAS

periodic acid-Schiff

- Pbm

basement membrane perimeter

- TGF-β1

transforming growth factor-β1

- TRP

triptolide

- TWHF

Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F

- WAm

area of airway smooth muscle

- WAt

area of airway wall

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interests.

References

- 1.Banasiak NC. Childhood asthma practice guideline part three: update of the 2007 National Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Asthma. The National Asthma Education and Prevention Program. J Pediatr Health Care. 2009;23:59–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hassan M, Jo T, Risse PA, Tolloczko B, Lemière C, Olivenstein R, Hamid Q, Martin JG. Airway smooth muscle remodeling is a dynamic process in severe long-standing asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:1037–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Trifilieff A, El-Hashim A, Bertrand C. Time course of inflammatory and remodeling events in a murine model of asthma: effect of steroid treatment. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279:1120–8. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.6.L1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar RK, Herbert C, Thomas PS, Wollin L, Beume R, Yang M, Webb DC, Foster PS. Inhibition of inflammation and remodeling by roflumilast and dexamethasone in murine chronic asthma. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;307:349–55. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.053819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Le AV, Cho JY, Miller M, McElwain S, Golgotiu K, Broide DH. Inhibition of allergen-induced airway remodeling in Smad 3-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2007;178:7310–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.7310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robinson DS, Campbell DA, Durham SR, Pfeffer J, Barnes PJ, Chung KF. Asthma and Allergy Research Group of the National Heart and Lung Institute. Systematic assessment of difficult-to-treat asthma. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:478–83. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00017003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Busse W, Banks-Schlegel S, Noel P, Ortega H, Taggart V, Elias J, for NHLBI Working Group Future research directions in asthma: an NHLBI working group report. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:683–90. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200311-1539WS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inman M. Is there a place for anti-remodelling drugs in asthma which may not display immediate clinical efficacy? Eur Respir J. 2004;24:1–2. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00044304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan EW, Cheng SC, Sin FW, Xie Y. Triptolide induced cytotoxic effects on human promyelocytic leukemia, T cell lymphoma and human hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines. Toxicol Lett. 2001;122:81–7. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(01)00353-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang WT, Kang JJ, Lee KY, Wei K, Anderson E, Gotmare S, Ross JA, Rosen GD. Triptolide and chemotherapy cooperate in tumor cell apoptosis. A role for the p53 pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:2221–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009713200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen BJ. Triptolide, a novel immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory agent purified from a Chinese herb Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F. Leuk Lymphoma. 2001;42:253–65. doi: 10.3109/10428190109064582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Y, He J, Liang B, Song Z. The effect of triptolide on the proliferation of airway smooth muscle and the expression of c-fos and c-jun in asthmatic rats. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2002;25:280–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mao H, Chen XR, Yi Q, Li SY, Wang ZL, Li FY. Mycophenolate mofetil and triptolide alleviating airway inflammation in asthmatic model mice partly by inhibiting bone marrow eosinophilopoiesis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2008;8:1039–48. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin Y, Wang C, Wang C. mRNA expression of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in airway tissues of asthma guinea pigs: effect of tripholide. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 1997;20:291–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang SP, Liang RY, Yang L, Yang L, Zhang W, Lü ZQ. Effects of triptolide on serum cytokine levels symptoms and pulmonary function in patients with steroid-resistant asthma. Chin J Pathophysiol. 2006;22:1571–4. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heldin CH, Miyazono K, ten Dijke P. TGF-beta signaling from cell membrane to nucleus through SMAD proteins. Nature. 1997;390:465–71. doi: 10.1038/37284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bartram U, Speer CP. The role of transforming growth factor-β in lung development and disease. Chest. 2004;125:754–65. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.2.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minshall EM, Leung DY, Martin RJ, Song YL, Cameron L, Ernst P, Hamid Q. Eosinophil-associated TGF-β1 mRNA expression and airways fibrosis in bronchial asthma. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;17:326–33. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.17.3.2733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamaguchi M, Niimi A, Matsumoto H, et al. Sputum levels of transforming growth factor-beta 1 in asthma: relation to clinical and computed tomography findings. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2008;18:202–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Temelkovski J, Hogan SP, Shephered DP, Foster PS, Kumar RK. An improved murine model of asthma: selective airway inflammation, epithelial lesions and increased methacholine responsiveness following chronic exposure to aerosolised allergen. Thorax. 1998;53:849–56. doi: 10.1136/thx.53.10.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanaka H, Masuda T, Tokuoka S, Komai M, Nagao M, Takahashi Y, Nagai H. The effect of allergen-induced airway inflammation on airway remodeling in a murine model of allergic asthma. Inflamm Res. 2001;50:616–24. doi: 10.1007/PL00000243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komai M, Tanaka H, Masuda T, Nagao K, Ishizaki M, Sawada M, Nagai H. Role of Th2 responses in the development of allergen induced airway remodelling in a murine model of allergic asthma. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;138:912–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Padrid P, Snook S, Finucane T, Shiue P, Cozzi P, Solway J, Leff AR. Persistent airway hyperresponsiveness and histologic alterations after chronic antigen challenge in cats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:184–93. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.1.7812551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matta R, Wang X, Ge H, Ray W, Nelin LD, Liu Y. Triptolide induces anti-inflammatory cellular responses. Am J Transl Res. 2009;1:267–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee SY, Kim JS, Lee JM, et al. Inhaled corticosteroid prevents the thickening of airway smooth muscle in murine model of chronic asthma. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2008;21:14–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.James AJ. Relationship between airway wall thickness and airway hyperresponsiveness. In: Stewart AG, editor. Airway Wall Remodeling in Asthma. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1997. pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jiang XH, Wong BC, Lin MC, Zhu GH, Kung HF, Jiang SH, Yang D, Lam SK. Functional p53 is required for triptolide-induced apoptosis and AP-1 and nuclear factor-kappaB activation in gastric cancer cells. Oncogene. 2001;20:8009–18. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lou YJ, Jin J. Triptolide down-regulates bcr-abl expression and induces apoptosis in chronic myelogenous leukemia cells. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45:373–6. doi: 10.1080/1042819031000139710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fidler JM, Li K, Chung C, Wei K, Ross JA, Gao M, Rosen GD. PG490-88, a derivative of triptolide, causes tumor regression and sensitizes tumors to chemotherapy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:855–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phillips PA, Dudeja V, McCarroll JA, Borja-Cacho D, Dawra RK, Grizzle WE, Vickers SM, Saluja AK. Triptolide induces pancreatic cancer cell death via inhibition of heat shock protein 70. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9407–16. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang S, Chen J, Guo Z, et al. Triptolide inhibits the growth and metastasis of solid tumors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:65–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krishna G, Liu K, Shigemitsu H, Gao M, Raffin TA, Rosen GD. PG490-88, a derivative of triptolide, blocks bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:997–1004. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64046-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cho JY, Miller M, McElwain K, McElwain S, Broide DH. Combination of corticosteroid therapy and allergen avoidance reverses allergen-induced airway remodeling in mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:1116–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu W, Ou Y, Li Y, et al. A small molecule triptolide suppresses angiogenesis and invasion of human anaplastic thyroid carcinoma cells via down-regulation of NF-κB pathway. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:812–9. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.052605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]