Abstract

As a first step to quantify [H+] changes in brain during ischemia we used H+-selective microelectrodes and enzyme fluorometric techniques to describe the relationship between interstitial [H+] ([H+]o) and peak tissue lactate after cardiac arrest. We found a step function relationship between [H+]o and tissue lactate rather than the linear titration expected in a homogeneous protein solution. Within a blood glucose range from 3–7 mM, brain lactate rose from 8–13 mmol/kg along with a rise in [H+]o of 99 ± 6 nM (0.44 ± 0.02 pH). At higher blood glucose levels (17–80 mM), brain lactate accumulated to levels of 16–31 mmol/kg; concurrently [H+]o rose by 608 ± 16 nM (1.07 ± 0.02 pH). The unchanging level of [H+]o between 8–13 and 16–31 mmol/kg lactate implies that [H+]o is at a steady-state, but not equilibrium with respect to [H+] in other brain compartments. We propose that ion-transport characteristics of astroglia account for the observed relationship of [H+]o to tissue lactate during complete ischemia and suggest that brain infarction develops after plasma membranes in brain cells can no longer transport ions to regulate [H+].

Keywords: buffer, glial cell, hydrogen ion, pH, brain ischemia, lactate, hyperglycemia, hydrogen ion microelectrode

INTRODUCTION

Complete brain ischemia imposed during normoglycemia results in selective neuronal destruction; other tissue elements are spared and tissue lactate accumulates to a level of up to 13 mmol/kg39. By contrast, equivalent degrees and duration of ischemia delivered during hyperglycemia produce brain infarction with necrosis of all tissue elements40. Concomitantly, lactate levels rise to greater than 16 mmol/kg40. It has been postulated that lactic acidosis (hydrogen ion concentration ([H+]) greater than normal) may cause severe ischemic brain injury33. If so, the micro-physiological mechanisms and degree of this putative damage remain undefined. Furthermore, the relationship of brain lactate content to [H+] in cellular or interstitial compartments is unknown and difficult to predict because of the dynamic and interactive mechanisms for [H+] homeostasis between brain cells and their microenvironment. An understanding of the molecular processes for [H+] homeostasis in brain is needed to provide a more quantitative interpretation of interrelated biochemical reactions and physiological processes during ischemia and subsequent ischemic brain injury.

In the present study we used H+-selective, liquid-membrane, double-barrelled microelectrodes and enzyme fluorometric techniques to examine the relationship between interstitial [H+] ([H+]o) and peak tissue lactate content during complete ischemia. As will be shown, a step function relationship was found between [H+]o and peak tissue lactate levels rather than the linear titration expected in a homogeneous protein solution31. The result suggests that net H+ movement out of cells reflects steady-state but not equilibrium conditions for at least the first 3–5 minutes of complete ischemia. The changes in [H+]o can be accounted for by alterations in the carbonic acid-buffer system of the brain. A preliminary report of some aspects of this work has appeared26.

METHOD

Twenty-one male Wistar rats (250–400 g) were anesthetized with halothane (5% induction; 3% maintenance during surgery; 1.5–2.0% during recording) and spontaneously ventilated with a 30% oxygen-nitrogen mixture via a modified inhalation mask29. The tail artery and femoral vein were cannulated and a 1–2 mm craniotomy was made 1 mm caudal to bregma and 2–3 mm lateral to the sagittal suture. The animals were then mounted in a head holder and warmed to 37 °C with a water jacket. Warmed normal (37 °C) Ringer solution flowed through a superfusion cup placed around the craniotomy site24. H+ ion selective micropipettes (ISMs) were positioned 800 μm down in the paramedian neocortex. Arterial pH, oxygen tension (pO2) and carbon dioxide tension (pCO2) were stabilized and measured with a Corning 158 blood gas analyzer. Selected animals were given an intraperitoneal injection of 0.93 M D-glucose (8.35 g/kg) or an intravenous injection of regular insulin (2.0–6.0 units/kg of U-100 Iletin). Blood glucose was measured with a Glucometer (Miles Laboratories). When animals achieved the desired blood glucose concentration, complete ischemia (cardiac arrest) was created by intravenous injection of 1 ml of 1 M KCl. When brain [H+]o reached a plateau, animals were decapitated and their heads were quickly dropped into liquid nitrogen. Samples of the neocortex from the recording zone were dissected from whole brains at −25 °C. The brain sections were powdered under liquid nitrogen and the frozen powders were weighed (20–30 mg) on a precision balance (Roller–Smith). The weighed powders were layered over 75 μl of frozen 3.0 M perchloric acid and further processed as previously described39. Enzyme fluorometric techniques were used to measure tissue lactate53, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), adenosine diphosphate (ADP), phosphocreatine (PCr) and creatine (Cr)30.

H+ ISMs were constructed as previously described24, 34 using a H+-selective ion exchanger based on tridodecylamine (Fluka Chemical)3 and connected to unity-gain, high-performance buffer amplifiers. Ion and reference signals were processed through 5-Hz active filters (Burr Brown) and subtracted via an instrumentation differential amplifier (Analog Devices 521K) to yield the pure electrochemical signal for [H+]. [H+]o, DC slow potentials and blood pressure (measured with a Statham P-50 pressure transducer) were recorded on a Gould 2600S chart recorder. An indifferent macroelectrode containing Ag–AgCl–1 M KCl/3.5% agar was positioned on muscle adjacent to the craniotomy site. Electrodes and [H+] recordings were calibrated as previously described24; pH calibrating solutions were referenced to Fisher pH standards measured with a glass pH electrode (Thomas 4094-L15) on an Altex/Beckman pH meter (PHI-71). H+ ISM responses were corrected for temperature through the Nicholsky equation10. Sodium bicarbonate-based standards were also corrected for animal superfusion temperature (37 °C) by estimating changes in carbonic acid equilibrium constants and carbon dioxide solubility32, 46 from pH measurements made with the Thomas pH electrode at 25 °C. Calibration data were fitted to a least squares best fit of mV vs pH and animal experimental data were referenced to this calculated line.

Brains from halothane-anesthetized and spontaneously breathing rats were frozen with liquid nitrogen by the method of Pontén37 for titration as homogenates. Samples of cerebral cortex (150–200 mg) were dissected from whole brains at −25 °C and then homogenized in 100 mM sodium fluoride (3 ml) under mineral oil at 25 °C. Homogenate pH was measured with a glass pH electrode (Thomas 4094-L15) on an Altex/Beckman pH meter (PHI-71) while 50 μl aliquots of 0.01 M lactic acid were added with stirring. Sodium fluoride pH had previously been adjusted to 7.00 with sodium hydroxide.

RESULT

Rats were divided into two groups, one with blood glucose levels of 3–7 mM (normoglycemic) and the other with blood glucose levels of 17–80 mM (hyperglycemic). Blood (Table I) and brain (Table II) physiologic variables were similar in all animals. Spontaneously breathing, normothermic rats under normoxic conditions had a mild respiratory acidosis as a result of halothane anesthesia (Table I). Control animals that did not experience ischemia had levels of brain high-energy phosphate reserves and lactate content that are normal for the state of mild hypercarbia22,39 (Table II) After cardiac arrest when [H+]o reached a plateau, high-energy phosphates declined to similar levels in all rats (Table II). Brain lactate rose to 7.80–12.80 mmol/kg in normoglycemic animals and to 16.30–31.30 mmol/kg in hyperglycemic animals. High-energy phosphate values from animals whose brain lactate rose to 13–16 mmol/kg were not included in the averages shown in Table II but were similar.

TABLE I.

Blood physiologic variables

| Controls (n = 2) | Preischemia |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood glucose 3–7 mM (n = 5) | Blood glucose 17–80 mM (n = 14] | ||

| Rectal temperature (°C) | 37 ± 0.5 | 37 ± 0.5 | 37 ± 0.5 |

| pH | 7.31 ± 0.02 | 7.30 ± 0.02 | 7.23 ±0.03 |

| pO2(mm Hg) | 110 ± 3 | 104 ± 2 | 122 ± 7 |

| pCO2 (mm Hg) | 59 ± 3 | 59 ± 5 | 67 ± 7 |

| Systolic pressure (mm Hg) | 103 ± 0 | 119 ± 1 | 109 ± 3 |

Values are mean ± S.E.M.

TABLE II.

Brain physiologic variables

| Preischemia | Ischemia |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood glucose 3 - 7 rnM | Blood glucose 17–80 rn M | ||

| pHo | 7.25 ± 0.02 (n=21)* | 6.81 ± 0.02 (n=5) | 6.18 ± 0.02 (n=12) |

| [H+]o (nM) | 56 ± 2 (n = 21)* | 155 ± 8 (n = 5) | 664 ± 20 (n = 12) |

| ΔpHo | 0.44 ± 0.02 (n = 5) | 1.07 ± 0.02 (n = 12) | |

| Δ [H+]o (nM) | 99 ± 6 (n=5) | 608 ± 16 (n= 12) | |

| lactate (mmol/kg) | 1.04 ± 0.03 (n = 5) | 7.80 – 12.80 (n = 5) | 16.30 – 31.30 (n = 12) |

| ATP (mmol/kg) | 3.41 ± 0.13 (n=5) | 0.09 ± 0.01 (n=5) | 0.14 ± 0.01 (n=14) |

| ADP (mmol/kg) | 0.39 ± 0.04 (n = 5) | 0.37 ± 0.00 (n = 5) | 0.41 ± 0.01 (n = 8) |

| PCr (mmol/kg) | 4.92 ± 0.06 (n=5) | 0.09 ± 0.01 (n=5) | 0.11 ± 0.01 (n=14) |

| Cr (mmol/kg) | 5.06 ± 0.15 (n = 5) | 10.34 ± 0.36 (n = 5) | 10.45 ± 0.17 (n = 8) |

Represents preischemic brain [H+]o

Values are mean ± S.E.M.

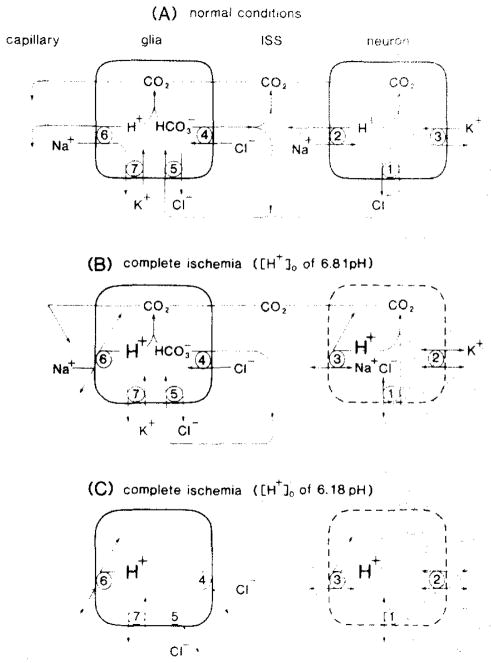

[H+]o in brain rose as blood pressure fell (Fig. 1). The rate of [H+]o change was insignificantly slower (0.15 vs 0.22 pH/min) in normoglycemic animals compared to hyperglycemic ones. A characteristic24 brief alkaline-going transient coincided with the development of a slow DC potential after cardiac arrest. Similar DC changes have been correlated with neuronal depolarization during ischemia5,13,14. Brain [H+]o rose to a new plateau in about 3 min in normoglycemic animals (Fig. 1A) and 5 min in hyperglycemic animals (Fig. 1B). With blood glucoses at 3–7 mM and ischemic brain lactates of 8–13 mmol/kg, [H+]o increased by 99 ± 6 nM (0.44 ± 0.02 pH; Fig. 1A; Table II). With blood glucoses of 17–80 mM, ischemic brain lactates rose to 16–31 mmol/kg and [H+]o increased by 608 ± 16 nM (1.07 ± 0.02 pH) (Fig. 1B; Table II). With brain lactate values between 13–16 mmol/kg, [H+]o underwent an intermediate change.

Fig. 1.

[H+]o changes during complete ischemia. A typical recording of [H+]o (upper trace) and simultaneous DC signal (middle trace) is shown from a double-barrelled H+ ISM positioned 800 μm deep in the paramedian neocortex prior to cardiac arrest induced by intravenous KCl injection (bottom trace). Animals were pretreated with insulin or glucose to alter brain glucose and brain lactate production during ischemia. In the presence of low brain carbohydrate stores (A), lactate production rose to 8–13 mmol/kg during ischemia and [H+]o changed by an average of 0.44 pH (99 nM). By contrast, in the presence of high brain carbohydrate stores (B), lactate rose to 16–31 mmol/kg associated with an average [H+]o change of 1.07 pH (608 nM). High-energy phosphate reserves fell to similar levels in the above two experiments.

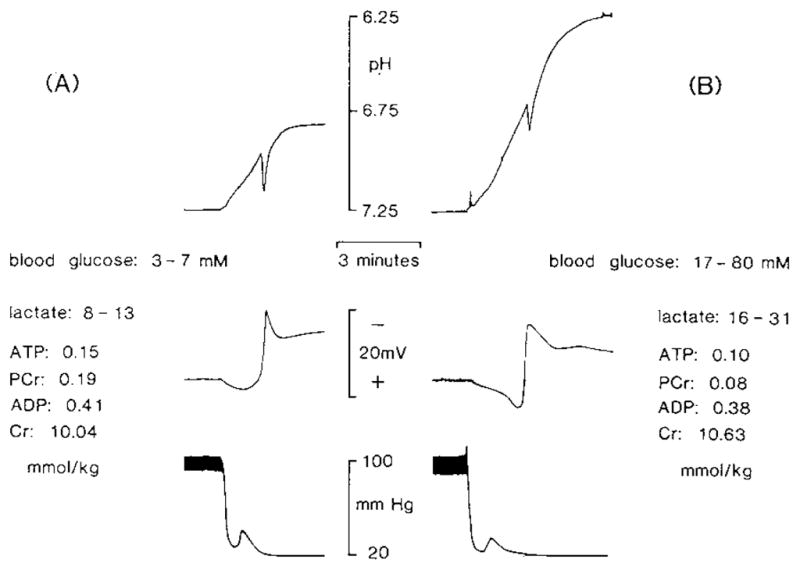

H+ is generated in a 1:1 stoichiometric relationship with lactate in completely ischemic brain1,27. Therefore, if lactic acid produced in cells mixes with the interstitial space, [H+]o should rise in direct proportion to the total brain lactate content (see below). Instead, peak [H+]o levels in normoglycemic and hyperglycemic animals were bimodally distributed according to tissue lactate content (Fig. 2). In spite of the fact that preischemic blood glucoses ranged from 3–7 mM and brain lactates ranged from 8–13 mmol/kg in normoglycemic animals, [H+]o always rose by a constant amount of 99 ± 6 nM (0.44 ± 0.02 pH). Similarly, although preischemic blood glucoses ranged from 17–80 mM and brain lactates ranged from 16–31 mmol/kg in hyperglycemic animals, [H+]o always rose by a constant, but larger, amount of 608 ± 16 nM (1.07 ± 0.02 pH).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of peak changes in [H+]o with lactate production during complete ischemia. Change in [H+]o measured with an ISM is shown compared to lactate assessed by enzyme fluorometric techniques from tissue frozen in liquid nitrogen at the peak [H+]o change (black dots). [H+]o rose by 99 ± 6 nM (0.44 ± 0.02 pH; n = 5) until lactate reached 13 mmol/kg at which point [H+]o abruptly rose 608 ± 16 nM (1.07 ± 0.02 pH; n = 12) by 16 mmol/kg lactate and remained constant through 31 mmol/kg lactate. [H+]o values are listed as the change in [H+]o from baseline (preischemia) to peak [H+]o so as to discount interanimal baseline variability. To the right in the figure average pH values are shown which correspond to the measured [H+]o changes compared to an average baseline pH of 7.25 (Table II).

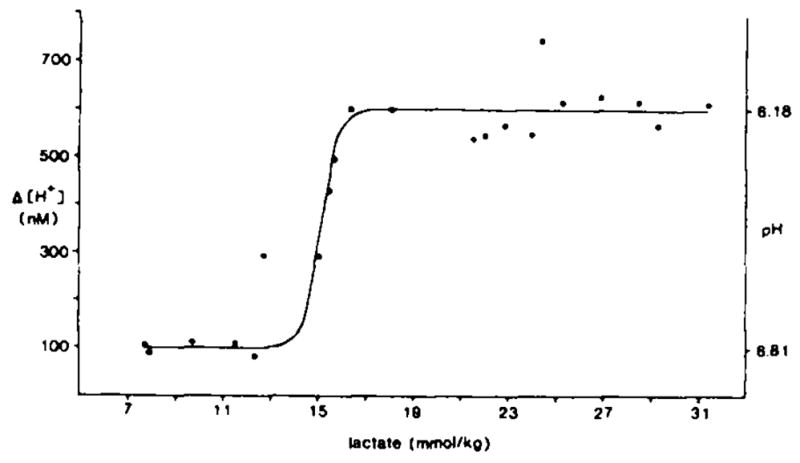

Simple titrations of a strong acid against a H+-buffered solution produce at least a slightly graded increase in [H+] to progressively greater acid concentrations. To examine how brain physicochemical H+ buffers might limit [H+] at lactate concentrations approximating those encountered in these experiments, we titrated diluted rat cerebral cortex homogenates with lactic acid (Fig. 3). The pH fell steadily without inflection from 7.00 to 6.00 as we added lactic acid up to about 40 mM/kg of brain homogenate. Such a linear relationship would be expected for H+ titration of a protein solution where H+ buffer equilibrium constants could be expected to be evenly distributed31 over physiologic pH (6.6–7.7)47. The result (Fig. 3) confirmed that physicochemical processes alone cannot explain the step function relationship found between [H+]o and peak tissue lactate during complete ischemia (Fig. 2). Instead, the progressive rise in tissue lactate unaccompanied by a change in peak [H+]o between 8–13 and 16–31 mmol/kg lactate implies that brain [H+] must be partitioned unequally between cellular and interstitial compartments during the early minutes of complete ischemia.

Fig. 3.

Titration of rat cerebral cortex homogenate. Solid line shows the change in pH produced when lactic acid (mmol/kg brain) was added to a homogenate of rat cerebral cortex in 100 mM sodium fluoride while under mineral oil. Note that [H+] rose steadily without an inflection. For comparison the data from Fig. 2 are superimposed here as a dotted line.

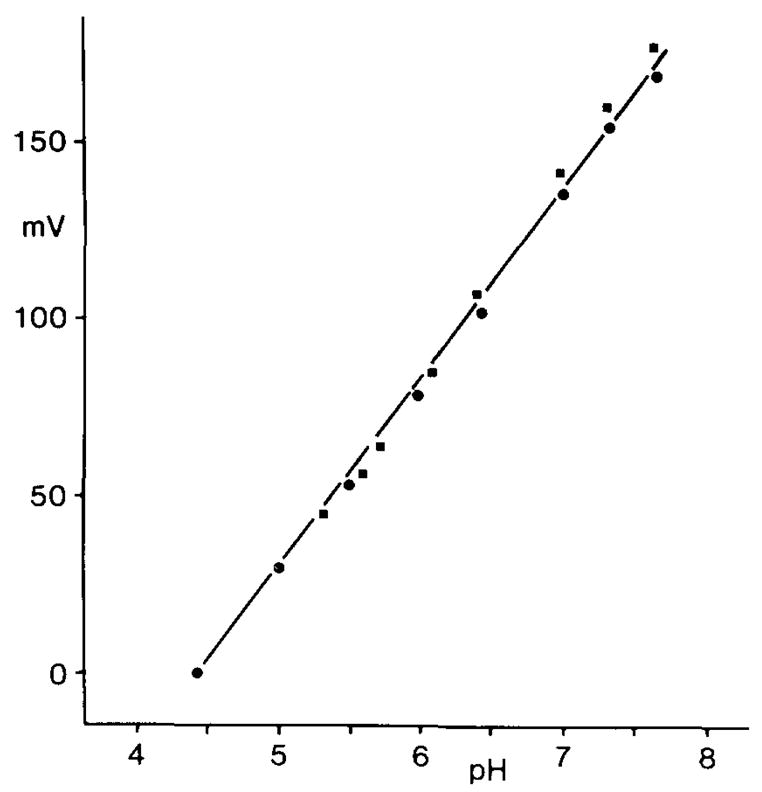

To determine if unknown anions2 released to the interstitial space during ischemia 24,34 could have influenced the response of the H+ ISM to changes in [H+]o we examined the H+ ISM response in rat brain homogenates exposed to several different [H+]. A linear H+ ISM response occurred with addition of homogenate to potassium hypophosphate solutions buffered with sodium hydroxide over a [H+] range between pH 4.4 to 7.6 (Fig. 4). It is known that H+ ISMs such as those used in this study do not suffer from biologically important cation interferences3. Therefore, the result makes it unlikely that the constant peak levels of [H+]o observed during complete ischemia in vivo reflected an artifact of interfering ions.

Fig. 4.

Response of an H+ ISM to changes in [H+]. Potassium hypophosphate solutions were buffered to different [H+] with sodium hydroxide (solid dots) to show the linearity (r = 0.999) and sensitivity (53 mV/decade change in [H+]) of liquid membrane H+ ISMs based on the neutral H+ ionophore tridodecylamine. Potential electrode interference by brain macromolecules and their breakdown products during ischemia was assessed by adding aliquots of rat cerebral cortex homogenates to the original buffer solutions (solid squares). The addition of homogenates of cerebral cortex to the original buffer solutions did not degrade the linearity (r = 0.999) or sensitivity (57 mV/decade change in [H+]) of the H+ ISM.

DISCUSSION

Excess H+ is produced according to a 1:1 stoichiometric relationship with lactate during ischemia1,27. However, the [H+] in any brain compartment (intracellular or interstitial) cannot be predicted on simple physical-chemical grounds from net tissue lactate concentrations because of the different H+ regulatory mechanisms in a multicompartment system. Brain-cell H+ buffering includes at least 3 physiologic and chemical mechanisms: 1) metabolic production and consumption of acids and bases; 2) ion transport across membranes; 3) physicochemical H+ buffers47. All 3 processes begin to change simultaneously when [H+] is perturbed but they adjust [H+] to a new steady-state at different rates in various brain compartments43. H+ ISMs can accurately detect rapid changes in [H+] in a single brain compartment such as the interstitial space but thus far have not been used in a detailed study of [H+] homeostasis during ischemia.

This study reports brain [H+]o changes during complete ischemia as a first step in trying to quantify [H+] homeostasis in mammalian brain ischemia. In the cardiac arrest model studied, the absence of blood flow prevented escape of excess H+ or CO2 from brain. It is known that about 106 mM Na+- and 57 mM Cl− are lost from the interstitial space within a minute or two of the onset of ischemia15. After that only residual ion gradients, which exist across intact plasma membranes, or cell physicochemical H+ buffers are likely to influence [H+] in any brain compartment. Furthermore, the examination of [H+] homeostasis in the interstitial space is simplified because the compartment contains only a single H+ buffer, carbonic acid. During the first minutes of complete ischemia, if cell membranes remain intact, other H+ buffers are unlikely to enter the interstitial space.

The present results imply that [H+]o is not at electrochemical equilibrium with [H+] in other brain compartments after 3–5 min of complete ischemia. If this is correct, energy in the form of membrane barriers or the potential energy of ion gradients across membranes must be present to explain the steady-state constancy of [H+]o despite the progressively increasing intracellular H+ content that the rising brain lactate level implies, H+ permeability of intact mammalian brain cell plasma membranes during conditions of ischemia has not been determined43. It is known, however, that negatively charged membranes can decrease their permeability to ions in the presence of increasing [H+] because of surface charge titration51. If intact brain-cell membranes behave similarly, their permeability to H+ may diminish as their adjacent microenvironment becomes more acidotic. Furthermore, since the effective hydrated ionic radius of H+ is 0.9 nm while the primary hydrate radii of other ions (Na+, K+, Cl−, HCO3−) lies between 0.3 and 0.4 nm8, excess H+ may be unable to diffuse passively from brain cells until the structural integrity of the cell membranes is disrupted.

H+ as such need not cross membrane-bound compartments to alter the [H+] in a second compartment. In biological fluids [H+] is determined by the tissue pCO2, the total weak acid concentration and the strong ion difference ([SID]) in any compartment24,34,48. The [SID] represents the sum of the strong base cations minus the sum of the strong acid anions. Important strong ions include sodium (Na+), potassium (K+), calcium, magnesium, chloride (Cl−) and lactate. Therefore, membrane impermeability to H+ could also mean that net changes in pCO2, total weak acid, or the [SID], are such that no net change in [H+] occurs in the interstitial space despite considerable change of H+ content in the intracellular space.

If plasma membranes remain intact during complete ischemia, the brain could be regarded as a 3-compartment system consisting of neurons, glia and interstitial space, each entirely bounded by plasma membranes. In mammalian brain, H+ ions are likely to cross plasma membranes via some combination of exchange transport (antiport) systems for Na+/H+ and Cl−/HCO3−. Electrically neutral Na+/H+ and Cl−/HCO3− antiport systems help to regulate intracellular [H+] ([H+]i) in several different kinds of animal cells including mammalian astroglia17,18,19, 20 and they may be important in H+ regulation in mammalian neurons as well, The transmembrane Na+ gradient sustained by a selective impermeability to Na+ across plasma membranes plus the action of energy-requiring Na+ pumps are thought to provide sufficient driving force to power both antiport systems43,50. Evidence suggests that in some cell types Cl−/HCO3− antiport may be an active process that requires ATP4. Experimental data indicate that two equivalents of intracellular H+ can be neutralized for each equivalent of Na+ entering and Cl− leaving a cell43. More than 20 years ago it was suggested that HCO3− secreted from brain cells buffered [H+]o 49. Interference with this mechanism has been invoked as a possible mechanism of tissue damage during brain ischemia36.

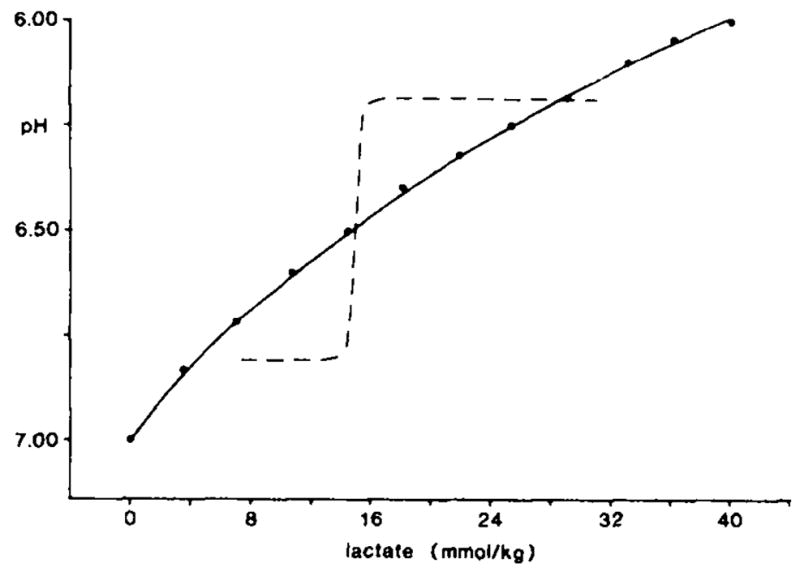

Studies of ion transport mechanisms by Kimelberg and his colleagues indicate that astroglial cells provide a major source of HCO3− in brain18 and may serve as important regulators of the organ’s [H+] homeostasis19,20. We have extended their theoretical model19 to include neurons (Fig. 5A) so as to postulate a mechanism (Fig. 5B and C) which may account for the observed relationship of [H+]o to tissue lactate described in Fig. 2. Na+/H+ and Cl−/HCO3− antiport systems for H+ regulation have not been demonstrated in mammalian neurons43. However, their ubiquity in other animal cell types43, including mammalian astroglia17,18,19,20 and vertebrate neurons6 suggests the likelihood of their presence in mammalian nerve cells as well.

Fig. 5.

Schematic representations of possible plasma membrane antiport systems for the regulation of brain [H+]. A: under normal conditions excess neuronal H+ could be neutralized to CO2 by HCO3− that entered through Cl−/HCO3− antiport (1). CO2 would rapidly move to blood because of its high diffusability through interstitial space (ISS) and cells. Alternatively, excess neuronal H+ could be moved to ISS by Na+/H+ antiport (2) energized by the transmembrane Na+ gradient created by Na+/K+ ATPase (3). Astroglia could manage excess H+ by the same antiport systems though two additional features are required (adapted from ref. 19). First. Na+/H+ (6) and Cl−/HCO3− (4) antiport systems would be on opposite sides of the cell so as to create a directional flux of H+ towards blood. Second. Cl−/HCO3− antiport would be directed as needed to provide HCO3− to ISS and neurons (1) or to buffer excess intraglial H+ (5). Since astroglia are likely to contain carbonic anhydrase, CO2 would be most readily hydrated in glia, thus helping to create a gradient of H+ toward blood (6) and HCO3− toward ISS and neurons (4). Na+/K+ ATPase (7) would return cellular Na+ to ISS and ISS K+ to astroglia. B: during ischemia [Na+]o and [Cl−]o fall by 106 mM and 57 nM, respectively (see ref. 51). Without a driving force for Na+/H+ antiport (2 and 6), excess H+ which could not passively leak from cells could be neutralized by Cl−/HCO3− antiport (1 and 5) to maintain pHo at 6.81. Once the total brain pool of HCO3− had been reduced so that Cl−/HCO3− antiport would no longer be feasible, excess H+ would be confined to acid-producing brain cells. C: during ischemia with lactate accumulation beyond 16 mmol/kg and no further change in [HCO3−]o only intracellular buffers could then limit further accumulation of H+i. If [H+]i rose sufficiently to alter the charge state, and therefore the conformation, of vital cell proteins, membrane and enzyme dysfunction might disable or kill brain cells. Stoichiometry for the proposed antiport systems is not specified.

Fig. 5A describes schematically a proposal for the movement of H+ from brain cells to blood without specific restrictions to stoichiometry. The theoretical basis for the diagram is as follows: under normal physiologic conditions excess H+ can leave neurons either by combining with intracellular HCO3− to form CO2 and water or by countertransport to the interstitial space by Na+/H+ antiport (Fig. 5A). In the interstitial space, excess H+ also combines with HCO3− to form CO2 and water. Excess CO2 which diffuses readily through cell compartments 12,16,28 quickly enters blood. CO2 also diffuses into astroglial cells to be rapidly hydrated to carbonic acid by carbonic anhydrase11,17,23,44,45. The speed by which carbonic anhydrase hydrates aqueous CO2 to carbonic acid and the subsequent ionization of that compound to H+ and HCO3− establishes a concentration gradient of H+ toward blood and HCO3− toward the interstitial space by Cl−/HCO3− antiport so as to maintain a constant total brain HCO3− pool of about 12 mmol/kg at normal arterial pCO238. In anesthetized rats where arterial pCO2 ranged from 59 to 67 mm Hg (Table I), predicted total brain HCO3− is about 14 mmol/kg22,42 (Kraig, unpublished observations).

Fig. 5B describes the hypothetical events during normoglycemic ischemia. During complete ischemia it is proposed that brain cells have a diminished ability to remove excess H+ because of a lowered transmembrane Na+ gradient. Large amounts of NaCl leave the interstitial space15,52 and are believed to enter dendrites52. Also neurons are likely to be depolarized in complete ischemia13,14. The constellation of a lowered transmembrane Na+ gradient and loss of membrane polarization should minimize efflux of H+ out of neurons via Na+/H+ antiport. Astroglia maintain a high degree of membrane diffusional impermeability to Na+ (and Cl−) when extracellular K+ is elevated to 54 mM54 in tissue culture and might also maintain an impermeability to Na+ in vivo during complete ischemia when extracellular K+ is known to rise to similar levels15. Since [Na+]o falls to 48 mM in complete ischemia15 while astroglial [Na+] is estimated to be around 20 mM under normal conditions20, the Na+ gradient across glial cell membranes may be too low to drive H+i out. If so, Cl−/HCO3− antiport could be the sole mechanism remaining for brain cells to remove excess H+ across intact plasma membranes during ischemia.

Changes in the carbonic acid buffer system of the brain could account for the observed relationship (Fig. 2) of [H+]o to tissue lactate during complete ischemia. Since peak [H+]o remained constant as tissue lactate climbed from 8 to 13 mmol/kg (Fig. 2) and brain pCO2 rose in a linear manner25, either [HCO3−]o increased proportionally or some new H+ buffer became available to the interstitial space to keep [H+]o constant. The abrupt rise in [H+]o between 13 to 16 mmol/kg lactate (Fig. 2) reflects a change from net secretion to absorption of interstitial HCO3− into increasingly acidotic cells. Note that this change is equivalent to a decrease in [SID]o (see Eqn. 1 below). The driving force for glial secretion of HCO3− between 8 to 13 mmol/kg lactate might be residual transmembrane ion gradients while the driving force for cellular uptake of interstitial HCO3− above 13 mmol/kg lactate might reflect a steep drop of cellular HCO3− stores producing a strong concentration gradient from the interstitial space towards acid-producing brain cells. Note that interstitial HCO3− could enter either neurons or glia. However, it is unlikely that all HCO3− leaves the interstitial space because [H+]o never goes below an average pH of 6.18. Why uptake of interstitial HCO3− should ultimately stop above ca. 16 mmol/kg lactate is unknown.

Fig. 5C describes the hypothetical acid–base events during complete hyperglycemic ischemia when lactate content exceeds ca. 16 mmol/kg (to 19 mmol/kg; see ref. 25). If the decline in interstitial HCO3− stopped when the effective aqueous concentration of CO2 approximated [HCO3−]o, [H+]o would reach a plateau near the first ionization constant of carbonic acid which is 7.352 × 10−7 eq/l at 37 °C and 6.18 pH32 (Kraig, unpublished observations). This can be seen from Eqn. (1) 34:

| (1) |

where K′1 is the first ionization constant for carbonic acid corrected for [H+], temperature and osmolality32; S′ is the solubility constant for CO2 in cerebrospinal fluid corrected for temperature32 (recall that S′pCO2 = aqueous [CO2]; and [SID]o is essentially equal to [HCO3−]o (refs. 24, 34, 48), (See ref. 34 for details of derivation of Eqn. 1.)

As Fig, 2 shows, during hyperglycemia, when lactate rose to between 16 to 31 mmol/kg, [H+]o reached a plateau of 6.607 × 10−7 eq/l, a value closely similar to that expected for the first ionization constant of carbonic acid, 7.352 × 10−7 eq/l. Under such circumstances [H+]o during complete ischemia might never fall below a pH of about 6.18 despite high tissue lactate content because of a loss of HCO3− from acid producing brain cells and the consequent absence of transmembrane HCO3− flux or rise in tissue pCO2 (Fig. 5C). If HCO3− stores are exhausted at this point in brain cells which continue to produce lactic acid, only the possible existence of other intracellular physicochemical H+ buffers could protect against development of excessive cellular acidosis followed by alterations of the charge state, configuration and, therefore, the function of vital cell proteins41. Infarction of the brain would be the expected result.

H+ is a major product of metabolism and its homeostasis is of profound biological importance to all organisms. Maintenance of the structure and functional integrity of vital cell proteins may be the key reason that cells and organisms have evolved complicated mechanisms to maintain the homeostasis of [H+]41. Throughout evolution carbonic acid, the histidine–imidazole complex and to a lesser extent, the N-terminal α-amino groups of proteins31 seem to have arisen as the primary physicochemical H+ buffering mechanisms of animal cells7. Pulmonary ventilation, renal excretion of H+ and chemical regulation of the vascular resistance of brain arterioles are additional physiologic mechanisms to control brain [H+]. Furthermore, Na+/H+ and Cl−/HCO3− antiport across plasma membranes are ion transport systems for the removal of excess cell H+ which appear to have been conserved throughout the animal world43 These exchange ion transport systems may have evolved to circumvent an impermeability of plasma membranes to H+ during severe acidosis.

Acknowledgments

It is a pleasure to acknowledge the support of NINCDS Grants NS-19108 and NS-003346 as well as by a Teacher Investigator Development Award (NS-00767) to R.P.K. In addition we would like to thank Dr. C. Nicholson and Dr. M. Chesler for helpful discussions about hydrogen ion homeostasis in brain.

References

- 1.Alberti KGMM, Cuthbert C. The hydrogen ion in normal metabolism: a review. In: Porter R, Lawrenson G, editors. Metabolic Acidosis, Ciba Foundation Svmposium. Vol. 87. Pitman; London: 1982. pp. 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ammann D, Bissing R, Cimerman Z, Fielder V, Güggi M, Morf WE, Oehme M, Osswald H, Pretsch E, Simon W. Synthetic neutral carriers for cations. In: Kessler M, Clark LC, Lübbers DW, Silver IA, Simon W, editors. Ion and Enzyme Electrodes in Biology and Medicine. University Park Baltimore: 1976. pp. 22–37. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ammann D, Lanter F, Steiner RA, Schulthess P, Shijo Y, Simon W. Neutral carrier based hydrogen ion selective microelectrode for extra- and intracellular studies. Analyt Chem. 1981;53:2267–2269. doi: 10.1021/ac00237a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boron WF, DeWeer P. Active proton transport stimulated by CO2/HCO3−, blocked by cyanide. Nature (Lond) 1976;259:240–241. doi: 10.1038/259240a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bureš J, Buresǒva O, Krivánek J. The Mechanism and Applications of Leão’s Spreading Depression of Electroencephalographic Activity. Ch 4. Academic Press; New York: 1974. pp. 72–86. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chesler C, Nicholson C. Regulation of intracellular pH in vertebrate central neurons. Brain Research. 1985;325:313–316. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90330-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen JJ, Kassirer JP. Comparative acid-base physiology. In: Cohen JJ, Kassirer JP, editors. Acid-Base. Little Brown; Boston: 1982. pp. 465–480. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dean JA, editor. Lang’s Handbook of Chemistry. 12. McGraw Hill; New York: 1979. pp. 5–5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edsall JT, Wyman J. Biophysical Chemistry. I. Academic Press; New York: 1958. pp. 550–590. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eisenmann G. Theory of membrane electrode potentials: an examination of the parameters determining the selectivity of solid and liquid ion exchangers and of neutral ion sequestering molecules. In: Durst RA, editor. Ion Selective Electrodes. Vol. 314. Nat. Bur. Stand. (U.S.) Spec. Publ; 1969. pp. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giacobini E. A cytochemical study of localization of carbonic anhydrase in the nervous system. J Neurochem. 1962;9:169–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1962.tb11859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gleichman U, Ingvar DH, Lübbers DW, Siesjö BK. Tissue pO2 and pCO2 of the cerebral cortex, related to blood gas tensions. Acta physiol scand. 1962;55:127–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1962.tb02425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grossman RG. Intracellular potentials of motor cortex neurons in cerebral ischemia. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1968;24:291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grossman RG, Williams VF. Electrical activity and ultrastructure of cortical neurons and synapses in ischemia. In: Brierly JB, Meldrum BS, editors. Brain Hypoxia. Lippincott; New York: 1971. pp. 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansen AJ. Extracellular ion concentrations during cerebral ischemia. In: Zeuthen T, editor. The Application of Ion-Selective Microelectrodes. Elsevier; New York: 1981. pp. 239–254. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaethner TM, Bangham AD. Selective compartmentation of the hydration products of carbon dioxide in liposomes, and its role in regulating water movement. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1977;468:157–161. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(77)90158-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimelberg HK, Biddlecome S, Narumi S, Bourke RS. ATPase and carbonic anhydrase activities in bulk-isolated neuron, glia and synaptosome fractions from rat brain. Brain Research. 1978;141:305–323. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimelberg HK, Bourke RS. Anion transport in the nervous system. In: Lajtha A, editor. Handbook of Neurochemistry, Vol. 1, Chemical and Cellular Architecture. 2. Plenum; New York: 1982. pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimelberg HK, Bourke RS, Stieg PE, Barron KD, Hirata H, Pelton EW, Nelson LR. Swelling of astroglia after injury to the central nervous system: mechanisms and consequences. In: Grossman RG, Gildenbery PL, editors. Head Injury: Basic and Clinical Aspects. Raven; New York: 1982. pp. 31–44. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kimelberg HK, Bowman C, Biddlecome S, Bourke RS. Cation transport and membrane potential properties of primary astroglial cultures from neonatal rat brains. Brain Research. 1979;177:533–550. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90470-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimelberg HK, Narumi S, Bourke RS. Enzymatic and morphological properties of primary rat brain astrocyte cultures and enzyme development in vivo. Brain Research. 1978;153:55–77. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)91128-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kjällguist A, Nardini M, Siesjö BK. The regulation of extra- and intracellular acid–base parameters in the rat brain during hyper- and hypocapnia. Acta physiol scand. 1969;76:485–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1969.tb04495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klumputainen T, Nyström HM. Immunohistochemical localization of carbonic anhydrase isoenzyme C in human brain. Brain Research. 1981;220:220–225. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(81)90230-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kraig RP, Ferreira-Filho CR, Nicholson C. Alkaline and acid transients in the cerebellar microenvironment. J Neurophysiol. 1983;49:831–849. doi: 10.1152/jn.1983.49.3.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kraig RP, Pulsinelli WA, Plum F. Carbonic acid buffer behavior in brain during complete ischemia. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 1984;10:888. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kraig RP, Pulsinelli WA, Plum F. Proton buffering of the brain during complete ischemia. Ann Neurol Abstr. 1984;16:111. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krebs HA, Woods HF, Alberti KGMM. Hyperlactatemia and lactic acidosis. Essays Med Biochem. 1975;1:81–103. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krogh A. The rate of diffusion of gasses through animal tissues, with some remarks on the coefficient of invasion. J Physiol (Lond) 1919;51:391–408. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1919.sp001838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levy DE, Zweiss A, Duffy TE. A mask for delivery of inhalation gases to small laboratory animals. Lab Anim Sci. 1980;30:868–870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lowry OH, Passonneau JV. A Flexible System of Enzymatic Analysis. Academic Press; New York: 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Madias NE, Cohen JJ. Acid–base chemistry and buffering. In: Cohen JJ, Kassirer JP, editors. Acid–Base. Little Brown; Boston: 1982. pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitchell RA, Herbert DA, Carman CT. Acid–base constants and temperature coefficients for cerebrospinal fluid. J Appl Physiol. 1965;20:27–30. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1965.20.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Myers RE. Lactic acid accumulation as cause of brain edema and cerebral necrosis resulting from oxygen deprivation. In: Korbkin R, Guilleminault G, editors. Advances in Perinatal Neurology. Spectrum; New York: 1979. pp. 85–114. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nicholson C, Kraig RP, Ferreira-Filho CR, Thompson P. Hydrogen ion variations and their interpretation in the microenvironment of the vertebrate brain. In: Kessler M, Harrison DK, Hoper J, editors. Recent Advances in the Theory and Application of Ion Selective Electrodes in Physiology and Medicine. Springer; New York: in press. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paljäirvi L, Söderfeldt B, Kalimo H, Olsson Y, Siesjö BK. The brain in extreme respiratory acidosis. Acta neuropath. 1982;58:87–94. doi: 10.1007/BF00691646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Plum F. What causes infarction in isehemic brain? Neurology. 1983;33:222–233. doi: 10.1212/wnl.33.2.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pontén U, Ratcheson RA, Salford LG, Siesjö BK. Optimal freezing conditions for cerebral metabolites in rats. J Neurochem. 1973;21:1127–1138. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1973.tb07567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pontén U, Siesjö BK. Acid-labile carbon dioxide of the rat brain after freezing the tissue in situ. Acta physiol scand. 1964;60:309–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1964.tb02894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pulsinelli WA, Duffy TE. Regional energy balance in rat brain after transient forebrain ischemia. J Neurochem. 1983;40:1500–1503. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1983.tb13599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pulsinelli WA, Waldman S, Rawlinson D, Plum F. Moderate hyperglycemia augments ischemic brain damage: a neuropthologic study in the rat. Neurology. 1982;32:1239–1246. doi: 10.1212/wnl.32.11.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reeves RB. An imidazole alphastat hypothesis for vertebrate acid-base regulation: tissue carbon dioxide content and body temperature in bullfrogs. Respir Physiol. 1972;14:219–236. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(72)90030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roos A. Intracellular pH and buffering power of rat brain. Amer J Physiol. 1971;221:176–181. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1971.221.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roos A, Boron WF. Intracellular pH. Physiol Rev. 1981;61:296–434. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1981.61.2.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roussel G, Delaunoy J-P, Nussbaum J-L, Mandel P. Demonstration of a specific localization of carbonic anhydrase C in glial cells of rat CNS by an immunohistochemical method. Brain Research. 1979;160:47–55. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90599-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sapirstein VS. Carbonic anhydrase. In: Lajtha A, editor. Handbook of Neurochemistry. 2. Vol. 4. Plenum; New York: 1983. pp. 385–402. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siesjö BK. The solubility of carbon dioxide in cerebral cortical tissue from the cat at 37.5 °C. With a note on the solubility of carbon dioxide in water, 0.16 M NaCl and cerebrospinal fluid. Acta physiol, scand. 1962;55:325–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1962.tb02447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Siesjö BK, Messeter K. Factors determining intracellular pH. In: Siesjö BK, Sorensen SC, editors. Ion Homeostasis of the Brain. Munksgaard; Copenhagen: 1971. pp. 244–262. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stewart PA. How to Understand Acid–Base. Elsevier; New York: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Swanson AG, Rosengren H. Cerebrospinal fluid buffering during acute experimental respiratory acidosis. J Appl Physiol. 1962;17:812–814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thomas RC. The role of bicarbonate, chloride, and sodium ions in the regulation of intracellular pH in snail neurons. J Physiol. 1977;273:317–338. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1977.sp012096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tien H, Ti . Bilayer Lipid Membranes (BLM), Theory and Practice. Dekker; New York: 1971. pp. 155–157. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van Harreveld A, Schade JP. Chloride movements in cerebral cortex after circulatory arrest and during spreading depression. J Cell Comp Physiol. 1959;54:65–84. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1030540108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vannucci RC, Duffy TE. Influence of birth on carbohydrate and energy metabolism in rat brain. Amer J Physiol. 1974;226:933–940. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1974.226.4.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walz W, Hertz L. Intracellular ion changes of astrocytes in response to extracellular potassium. J Neurosci Res. 1983;10:411–423. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490100408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]