Abstract

Doxorubicin is one of the most effective molecules used in the treatment of various tumors. Contradictory reports often open windows to understand the role of p53 tumor suppressor in doxorubicin-mediated cell death. In this report, we provide evidences that doxorubicin induced more cell death in p53-negative tumor cells. Several cells, having p53 basal expression, showed increase in p53 DNA binding upon doxorubicin treatment. Doxorubicin induced cell death in p53-positive cells through expression of p53-dependent genes and activation of caspases and caspase-mediated cleavage of cellular proteins. Surprisingly, in p53-negative cells, doxorubicin-mediated cell death was more aggressive (faster and intense). Doxorubicin increased the amount of Fas ligand (FasL) by enhancing activator protein (AP) 1 DNA binding in both p53-positive and p53-negative cells, but the basal expression of Fas was higher in p53-negative cells. Anti-FasL antibody considerably protected doxorubicin-mediated cell death in both types of cells. Activation of caspases was faster in p53-negative cells upon doxorubicin treatment. In contrast, the basal expression of Ras oncoprotein was higher in p53-positive cells, which might increase the basal expression of Fas in these cells. Overexpression of Ras decreased the amount of Fas in p53-negative cells, thereby decreasing doxorubicin-mediated aggressive cell death. Overall, this study will help to understand the much studied chemotherapeutic drug, doxorubicin-mediated cell signaling cascade, that leads to cell death in p53-positive and -negative cells. High basal expression of Fas might be an important determinant in doxorubicin-mediated cell death in p53-negative cells.

Keywords: AP-1 Transcription Factor, Apoptosis, Drug Action, Interleukin, Ras, Doxorubicin, FasL, IL-8, JNK, NF-kB

Introduction

Doxorubicin, an anthracycline compound, is one of the most effective chemotherapeutic agents available to treat breast cancer and leukemia patients. The drug is able to induce regression of metastatic breast cancer (1, 2). Several reports suggest that it generates oxidative stress that leads to DNA damage and culminates in cell death through mitotic catastrophe (3–5). DNA damage activates p53, which in turn activates several genes such as p21, p17, etc., causing cell cycle arrest followed by apoptosis. Several tumor cells including breast cancer cells have a mutation in p53. Still, these cells are equally potent for cell death against several apoptosis-promoting agents. The oncogenic mutation in Ras family genes including H-, K-, and N-ras is often observed in several human cancers (5). Ras family proteins are predominantly involved in cell cycle progression. It has been reported that oncogenic Ras induces senescence and apoptosis through p53 activation (6). In hepatocellular carcinoma, restoration of p53 rapidly regressed H-ras (7). It is also reported that p53 can coexist with K-ras in human cancer tissues and cells (8). In a mouse model, the K-ras can progress tumor despite the intact p53 (9). Oncogenic K-ras has shown to repress p53 function by stabilizing the Snail (10).

Sustained elevation of calcium in cells keeps high calcineurin activity. The family of transcription factors of nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NF-AT)3 is the target substrate for calcineurin (11). Upon stimulation of calcineurin, several residues at the regulatory domain of NF-AT are dephosphorylated, and this leads to nuclear translocation of NF-AT and activation of target genes such as AP-1, MEF2, FasL, and GATA (11–13). As doxorubicin increases reactive oxygen species production, it promotes NF-κB activation via activation of IκB kinase complex. Aberrantly active NF-κB complexes can contribute to tumorigenesis by regulating genes that not only promote the growth but also survival of cancer cells (14, 15) and also induce resistance against doxorubicin (16). Doxorubicin has been shown to induce cell death via a non-classical pathway involving a biphasic induction of NF-κB, which in turn expresses interleukin-8 (IL-8), and this IL-8 induces cell death through a sequential process: increase in intracellular Ca2+ release, calcineurin activation, dephosphorylation of NF-AT, nuclear translocation of NF-AT, NF-AT-dependent FasL expression, FasL-mediated caspase activation, and induction of cell death (17). FasL expression again depends upon the transcriptional activation of AP-1 through activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) (18, 19). Expressed FasL acts through its specific receptor Fas and activates caspases, the cysteine proteolytic enzymes, which are reported to be the executioners of apoptosis. Oleandrin, a cardiac glycoside, has shown to induce cell death potently in several human cell types (11, 20, 21).

In this report, we have found that doxorubicin-mediated cell death is slow and less potent in p53-positive cells. Breast tumor cell line MCF-7 has basal expression of p53, whereas other breast cells such as SKBr3 and MDA-MB-231 have mutated p53 (22, 23). Cells, such as U-937 (monocytic cells), THP1 (monocytic macrophages), and HeLa (epithelial cells) have either mutated or no p53 expression (24, 25). HCT116 cells are knocked out of p53 by homologous recombination and designated as (HCT116 (p53−/−)), and non-transfected cells (HCT116 (Wild)) are used for this study. We have provided the evidences for the first time that p53-positive cells have high basal K-ras, but low Fas expression, which might dictate p53-positive cells for slow and less potent cell death mediated by doxorubicin than p53 mutant or null cells, although both types of cells showed equal expression of FasL upon treatment of doxorubicin. This study will help understand how p53, although it is a well known tumor suppressor, puts the brake via the Fas-Ras pathway on doxorubicin-mediated cell death, which might help target the specific molecules to regulate sensitization of p53-positive cells for aggressive cell death.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Doxorubicin, EDTA, EGTA, PMSF, propidium iodide, Ac-DVED-pNA, Ac-ITED-pNA, 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide) (MTT), glycine, oleandrin, and anti-tubulin antibody were obtained from Sigma. DMEM and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were obtained from Invitrogen. DAPI and goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 594 were purchased from Molecular Probes. Antibodies against p53, p21, PARP, JNK1, Fas, FasL, K-ras, IL-8, goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with HRP, and gel shift oligonucleotides for AP-1, NF-AT, and p53 were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Antibodies against phospho-JNK and SP-600125 (JNK inhibitor) were obtained from Calbiochem. The plasmid constructs for FasL-luciferase and NF-AT-luciferase were a kind gift from Prof. B. B. Aggarwal of the University of Texas, M.D. Anderson Cancer Center (Houston, TX). The K-ras wild type and mutant constructs were obtained from the Laboratory of Cancer Biology, Centre for DNA Fingerprinting and Diagnostics (CDFD), Hyderabad, India.

Cell Lines

MCF-7, SKB3, MDA-MB-231, U-937, HeLa, and THP1 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). HCT116 cells and p53 knock-out HCT116 cells were a kind gift from the Prof. B. Vogelstein laboratory (Johns Hopkins Oncology Center, Baltimore, MD).

NF-κB, AP-1, NF-AT, and p53 DNA Binding Assay

DNA binding activity of NF-κB, AP-1, NF-AT, and p53 was determined by EMSA (26). Briefly, after different treatments, cells, were used to prepare cytoplasmic extracts and nuclear extracts (NE). NE proteins (8 μg) were incubated with 32P end-labeled double-stranded NF-κB oligonucleotide of HIV-LTR, 5′-TTGTTACAAGGGACTTTCCGCTGGGGACTTTCCAGGGAGGCGTGG-3′, for 30 min at 37 °C and run on 6.6% native PAGE. Similarly, AP-1, NF-AT, and p53 were assayed using specific double-stranded labeled oligonucleotides. Visualization of radioactive bands was done in a Fluorescent Image Analyzer FLA-3000 (Fuji).

NF-AT- or FasL-dependent Luciferase Gene Transcription Assay

The expression of NF-AT- or FasL-dependent luciferase reporter gene was carried out as described previously (11). Cells were transiently transfected with SuperFect transfection reagent containing 0.5 μg of each reporter plasmid containing an NF-AT or a FasL binding site cloned upstream of luciferase (designated as NF-AT-luciferase or FasL-luciferase) and GFP constructs. After 3 h of transfection, cells were washed and cultured for 12 h. GFP-positive cells were counted. Transfection efficiency was observed as 37–40% in different transfection conditions. After various treatments, the cells were extracted with lysis buffer (part of the luciferase assay kit from Promega), and the extracts were incubated with the firefly luciferin (substrate from Promega). Light emission was monitored with a luminometer, and values were calculated as -fold of activation over vector-transfected value.

Cytotoxicity Assay

The cytotoxicity was measured by MTT assay (15). Briefly, cells (1 × 104 cells/well of a 96-well plate) were treated with different agents for the indicated concentrations and times, and thereafter, 25 μl of MTT solution (5 mg/ml in PBS) was added. After a 2-h incubation, 100 μl of extraction buffer (20% SDS in 50% dimethylformamide) was added. After an overnight incubation at 37 °C, absorbance was read at 570 nm with the extraction buffer as blank.

Determination of Nuclear Fragmentation

U-937, MCF-7, THP1, and HeLa cells were treated with doxorubicin. Cells were then harvested and fixed in 80% methanol, stained with propidium iodide, and viewed under a fluorescence microscope (20).

Determination of DNA Fragmentation

MCF-7 and HeLa cells were treated with doxorubicin and then harvested, and DNA was extracted following the method described earlier (20). Extracted DNA (2.0 μg) was analyzed by electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel. DNA fragments were visualized with ethidium bromide under UV light.

LIVE/DEAD Assay

The cytotoxicity was determined by the LIVE/DEAD assay (27) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Briefly, after different treatments, 1 × 105 cells were stained with the LIVE/DEAD cell assay reagent. Red (as dead) and blue (as live) cells were analyzed under a fluorescence microscope (Labophot-2, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunocytochemistry

The amount of Ras was examined by the immunocytochemical method as described (11). Briefly, cells were cultured on chamber slides, washed after different treatments, air-dried, fixed with 3.5% formaldehyde, and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100. Slides were blocked by 5% goat serum and incubated with anti-K-ras Ab for 8 h followed by incubation with goat anti-rabbit IgG-Alexa Fluor 594 for 1 h. Slides were mounted with mounting medium with DAPI and analyzed under a fluorescence microscope.

Caspase 3 and 8 Activities Assay

To evaluate caspase 3 and 8 activities, cell lysates were prepared after their respective treatments. 50 μg of the cell lysate proteins was incubated with 200 μm caspase 3 substrate (Ac-DVED-pNA) or caspase 8 substrate (Ac-ITED-pNA) in 100 μl of reaction buffer (1% Nonidet P-40, 20 μm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 137 mm NaCl, and 10% glycerol) and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. The release of chromophore pNA (para-nitroaniline) was monitored spectrophotometrically at 405 nm (11).

In Vitro JNK Assay

The JNK was assayed by a method described previously (28). Briefly, JNK complex from whole-cell extract (300 μg) was precipitated with anti-JNK1 antibody (1 μg) followed by incubation with protein A/G-Sepharose beads (Pierce). After a 2-h incubation, the beads were washed with lysis buffer and assayed for activity of JNK using 5 μg of GST-Jun (amino acids 1–100) substrate protein.

Western Blot

PARP, p21, p53, Fas, FasL, Ras, phospho-JNK, JNK1, and tubulin were detected by Western blot technique using specific antibodies followed by detection by chemiluminescence (Amersham Biosciences).

Reverse Transcription (RT)-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the standard TRIzol method, and 1 μg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA by the One-Step Access RT-PCR kit (Promega, Madison, WI) followed by amplification using gene-specific primers for FasL, caspase 8, and actin. PCR was performed, and amplified products were separated by agarose gel electrophoresis (2%) and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. The primer sequence and product size are as follows: FasL, 344 bp (forward) 5′-GGATTGGGCCTGGGGATGTTTCA-3′, (reverse) 5′-TTGTGGCTCAGGGGCAGGTTGTTG-3′; caspase 8, 380 bp (forward) 5′-TTATTCAGGCTTGTCAGG-3′, (reverse) 5′-GCACCATCAATCAGAAGGGAAG-3′; actin, 616 bp (forward) 5′-CCAACCGTGAAAAGATGACC-3′, (reverse) 5′-GCAGTAATCTCCTTCTGCATCC-3′.

Statistical Analysis

Results were expressed as mean ± S.D. of three independent experiments. Statistical analyses of the samples were done by the Student's t test wherever applicable. The p < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

In this study, the effects of doxorubicin in p53-positive and -negative cells were examined. Doxorubicin was used as a solution in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at 10 mm concentration. Further dilution was carried out in cell culture medium. The concentrations and duration of exposure of the chemicals employed in these studies had no effect on cytolysis as detected by lactate dehydrogenase assay from culture supernatant of treated cells (data not shown).

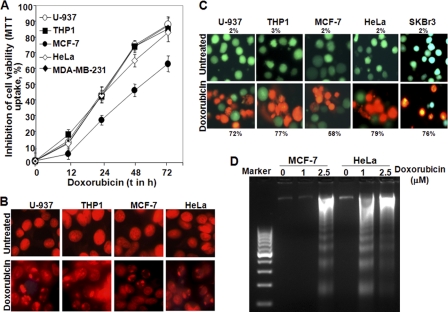

Doxorubicin Increases Cell Death More Potently in SKBr3, U-937, THP1, and HeLa Cells than MCF-7 Cells

Different cells were treated with 1 μm doxorubicin for different times, and an MTT assay was done to detect cell death. Doxorubicin increased cell death almost 15–25% at any time of treatment in U-937, THP1, HeLa, or MDA-MB-231 cells when compared with MCF-7 cells. At 72 h of doxorubicin treatment, cell death was observed at 88% (p < 0.005), 85% (p < 0.005), 83% (p < 0.01), 87% (p < 0.005), and 63% (p < 0.01) for U-937, THP1, HeLa, MDA-MB-231, and MCF-7 cells, respectively (Fig. 1A). Almost 20% more cell death was observed in SKBr3 cells than in MCF-7 cells at any concentration of doxorubicin when treated for 72 h (supplemental Fig. 1A). Nuclear fragmentation data as detected by propidium iodide-stained cell nuclei supported the similar cell death in these cells (Fig. 1B). Doxorubicin induced cell death at 72% (p < 0.01), 77% (p < 0.005), 58% (p < 0.005), 79% (p < 0.01), and 76% (p < 0.005) in U-937, THP1, MCF-7, HeLa, and SKBr3 cells, respectively, at 72 h of treatment as detected by the LIVE/DEAD assay (Fig. 1C). At 24 h of doxorubicin treatment, almost no DNA fragmentation was observed in MCF-7 cells, but HeLa cells showed sufficient DNA fragmentation (Fig. 1D). Partial PARP cleavage was observed at 48 and 72 h in MCF-7 cells upon doxorubicin treatment, although in THP1 cells, complete PARP cleavage was observed at the same time of treatment (supplemental Fig. 1B). Phase contrast microscope views for the doxorubicin-treated cells also suggested more cell death in HeLa cells when compared with MCF-7 cells (supplemental Fig. 1C). All these data suggest that doxorubicin-mediated cell death is faster and more potent in U-937, THP1, SKBr3, MDA-MB-231, and HeLa cells than MCF-7 cells.

FIGURE 1.

Effect of doxorubicin on induction of cell death in U-937, HeLa, THP1, SKBr3, and MCF-7 cells. A, THP1, U-937, HeLa, MDA-MB-231, and MCF-7 cells were treated with 1 μm doxorubicin for different times, and inhibition of cell viability was calculated from the MTT assay. B, U-937, THP1, MCF-7, HeLa, and SKBr3 cells were treated with 1 μm doxorubicin for 72 h. Cells were fixed, stained with propidium iodide, and viewed under a fluorescence microscope. U-937, THP1, HeLa, and MCF-7 cells were treated with doxorubicin (1 μm) for 72 h. Cells were incubated with LIVE/DEAD assay solution for 30 min. Cells were viewed under a fluorescence microscope. C, the number of apoptotic cells (red color) and live cells (green color) was counted, and the percentage of apoptotic cells is indicated in the figure. MCF-7 and HeLa cells were treated with doxorubicin (1 and 2.5 μm) for 24 h. Cells were harvested, and DNA was prepared and run in a 1.5% agarose gel. D, the gel was stained with ethidium bromide and viewed in Gel Doc.

Doxorubicin Increases Cell Death in More Potently in p53-negative Cells

Doxorubicin enhanced p53 DNA binding with increasing concentrations in MCF-7 cells, but not in SKBr3 cells (Fig. 2A). The p53 DNA binding was increased with increasing time of doxorubicin treatment in MCF-7 cells, but no significant p53 DNA binding was observed in U-937 cells (supplemental Fig. 2A). We have shown that doxorubicin induces p53 in MCF-7 cells, but not in U-937 or SKBr3 cells. MCF-7 cells have wild type p53, and SKBr3, U-937, THP1, or HeLa cells either are null for p53 or have mutated p53 (21, 22). To detect the role of p53 in differential cell death mediated by doxorubicin, we used HCT116 cells, having wild type p53 (HCT116 (Wild)), and p53 negative HCT116 cells in which p53 was knocked out by homologous recombination (HCT116 (p53−/−)). The high basal p53 DNA binding activity was marginally increased in HCT116 (Wild) cells with the increasing time of doxorubicin treatment, whereas HCT116 (p53−/−) cells did not show any basal p53 DNA binding and doxorubicin had no effect in altering the p53 DNA binding (Fig. 2B, upper panel). Doxorubicin showed biphasic NF-κB DNA binding in both p53-positive and p53-negative HCT116 cells (Fig. 2B, second upper panel). The amounts of p53 and p21 increased with increasing time of doxorubicin treatment in HCT116 (Wild) cells, but not in HCT116 (p53−/−) cells (Fig. 2B, lower panels). These data suggest that HCT116 (p53−/−) cells do not have p53 expression and that HCT116 (Wild) cells have basal expression of p53. Doxorubicin induces p53 and p53-dependent p21 gene in p53-positive cells. Doxorubicin induces biphasic activation of NF-κB. HCT116 (p53−/−) cells showed almost 20–25% more cell death than HCT116 (Wild) cells at any point of doxorubicin treatment (Fig. 2C). Doxorubicin treatment also showed almost 20–25% less cell death in HCT116 (Wild) cells than HCT116 (p53−/−) cells at any concentration (supplemental Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Effect of doxorubicin on induction of p53 and cell death in p53-positive and -negative cells. A, MCF-7 and SKBr3 cells were treated with different concentrations of doxorubicin for 24 h, and nuclear extracts were assayed for p53 DNA binding by gel shift assay. HCT116 cells (HCT116 (Wild)) and p53 knock-out cells (HCT116 (p53−/−)) were treated with 1 μm doxorubicin for different times. B, upper panels, NE were prepared, and 8 μg of NE proteins per sample was used to detect p53 and NF-κB by gel shift assay. Lower panels, whole-cell extracts were prepared, and 100 μg of proteins was used to detect p53 and p21 by Western blot. Blots were reprobed for tubulin. HCT116 p53+/+ and wild type cells were treated with 1 μm doxorubicin for different times, and cell viability was detected by MTT assay. C, inhibition of cell viability was indicated in the figure.

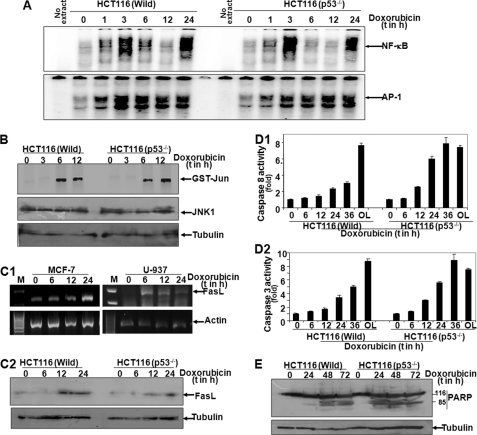

Doxorubicin Increases AP-1 DNA Binding, JNK Activation, FasL Expression, and Caspase Activation in Both p53-positive and p53-negative Cells

To understand the differential potency of doxorubicin-mediated cell death in p53-positive and -negative cells, we have measured the amount of FasL, which is transcriptionally regulated by AP-1 (18, 19), upon treatment of doxorubicin. Doxorubicin increased AP-1 DNA binding with increasing time of treatment as shown from the nuclear extracts by gel shift assay in both HCT116 (Wild) and HCT116 (p53−/−) cells (Fig. 3A, lower panel). It showed biphasic activation of NF-κB DNA binding in both types of cells (Fig. 3A, upper panel), which is supported by our previous observation (17). Doxorubicin almost equally induced JNK activation in both types of cells as shown by detecting the amount of phospho-JNK by Western blot (supplemental Fig. 3A) or by in vitro JNK assay using GST-Jun as substrate protein (Fig. 3B). The amount of FasL expression was almost equal in both of these cells upon doxorubicin treatment as shown by RT-PCR (Fig. 3C1), Western blot (Fig. 3C2), or FasL-dependent luciferase gene expression (supplemental Fig. 3B). The amount of caspase 8 expression was almost equal in both types of cells upon doxorubicin treatment as shown by RT-PCR data (supplemental Fig. 3C), whereas activities of caspase 8 (Fig. 3D1) and caspase 3 (Fig. 3D2) were much higher in than HCT116 (p53−/−) cells than HCT116 (Wild) cells upon doxorubicin treatment. The cleavage of PARP was more intense and faster in HCT116 (p53−/−) cells than HCT116 (Wild) cells (Fig. 3E). These data suggest that although the AP-1-dependent FasL expression is equal in both p53-positive and p53-negative cells, the activity of caspases is different in these cells.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of doxorubicin on induction of NF-κB, AP-1, p53, JNK, FasL, caspases, and PARP cleavage in p53-positive and -negative cells. A, HCT116 (p53−/−) and wild type cells were treated with 1 μm doxorubicin for different times. NE were prepared, and 8 μg of NE proteins per sample was used to detect NF-κB and AP-1 by gel shift assay. HCT116 (p53−/−) and wild type cells were treated with 1 μm doxorubicin for different times, and whole-cell extracts were prepared. 300 μg of whole-cell extracts was incubated with anti-JNK Ab (200 ng) for 2 h and then pulled down by protein A/G-Sepharose beads and assayed for JNK using 2 μg of GST-Jun as substrate protein and [γ-32P]ATP. The reaction mixture was boiled with SDS-PAGE Laemmli buffer and run in a 9% SDS-PAGE. B, the gel was dried and exposed to a phospho-screen, and the radioactive bands were detected as activity of JNK. MCF-7 and U-937 cells were treated with 1 μm doxorubicin for different times, and total RNA was extracted. C1, the amount of FasL was measured from total RNA by RT-PCR. M, Marker lane for DNA ladder. C2, HCT116 (p53−/−) and wild type cells were treated with 1 μm doxorubicin for different times, whole-cell extracts were prepared, and the amount of FasL was detected from 100 μg of proteins by Western blot. HCT116 wild type and p53−/− cells were treated with 1 μm doxorubicin for different times and harvested in lysis buffer. D1 and D2, cellular lysates were incubated with caspase 8 substrate (Ac-ITED-pNA) (D1) or caspase 3 substrate (Ac-DVED-pNA) (D2), and absorbance was recorded at 405 nm. Results are indicated as the percentage of caspase activities, considering 1-fold for untreated cells. Oleandrin (OL) (100 ng/ml) was used to treat the cells as a positive control. E, HCT116 (p53−/−) and wild type cells were treated with 1 μm doxorubicin for different times, and PARP was measured from 100 μg of whole-cell extracts.

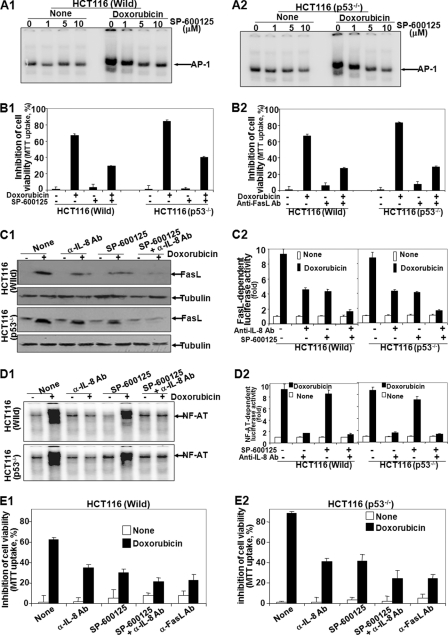

Inhibition of FasL Protects Doxorubicin-mediated Aggressive Cell Death in p53-negative Cells

To detect the role of FasL in aggressive cell death mediated by doxorubicin in p53-negative cells, both HCT116 (Wild) and HCT116 (p53−/−) cells were treated with different concentrations of SP-600125 (JNK inhibitor) and then stimulated with doxorubicin for 24 h. AP-1 DNA binding activity was assayed from nuclear extracts. As shown in Fig. 4, A1 and A2, doxorubicin-mediated AP-1 DNA binding decreased gradually with the increasing concentrations of SP-600125. The SP-600125 did not alter p53 DNA binding in MCF-7 or HCT116 (Wild) cells (supplemental Fig. 4A). Doxorubicin induced 67% (p < 0.005) and 84% (p < 0.01) cell death in HCT116 (Wild) and HCT116 (p53−/−) cells, respectively. In SP-600125-pretreated cells, doxorubicin induced cell death 29 and 40% in HCT116 (Wild) and HCT116 (p53−/−) cells, respectively (Fig. 4B1). This result suggests that almost 40% cell death is protected by JNK inhibitor. In anti-FasL Ab-pretreated cells, doxorubicin induced 28 and 29% cell death in HCT116 (p53−/−) and HCT116 (Wild) cells, respectively (Fig. 4B2). These data suggest that additive (almost 20%) cell death in HCT116 (p53−/−) cells is completely protected by anti-FasL Ab. As JNK inhibitor alone cannot block the additive cell death but anti-FasL Ab blocks it completely, we have looked at the possible other pathway for FasL expression, via IL-8 (17), in these cells. Both HCT116 (p53−/−) and HCT116 (Wild), when preincubated with anti-FasL or -IL-8 Ab and SP-600125 followed by treatment with doxorubicin, demonstrated that anti-IL-8 Ab- and SP-600125-preincubated cells showed complete inhibition, but anti-FasL Ab- and SP-600125-preincubated cells showed partial inhibition of AP-1 DNA binding (supplemental Fig. 4B). Anti-IL-8 Ab or SP-600125 partially but in combination completely inhibited FasL expression in both HCT116 (p53−/−) and HCT116 (Wild) cells as shown by the amount of FasL detected by Western blot (Fig. 4C1) and FasL-dependent luciferase activity (Fig. 4C2). These data suggest that expression of FasL is dependent upon IL-8-mediated signaling and AP-1-dependent transcription. As IL-8 expresses FasL via NF-AT (17), the DNA binding activity of NF-AT was completely inhibited by anti-IL-8 Ab, but not by SP-600125, as shown by gel shift assay (Fig. 4D1) or NF-AT-dependent luciferase activity assay (Fig. 4D2). These data further suggest that both IL-8-mediated expression and AP-1-dependent FasL expression interplay in doxorubicin-mediated cell death. Doxorubicin induced 63% (p < 0.005) and 87% (p < 0.01) cell death in HCT116 (Wild) and HCT116 (p53−/−) cells, respectively. In SP-600125- or anti-IL-8 Ab-preincubated cells, doxorubicin induced cell death 29 and 40% in HCT116 (Wild) and HCT116 (p53−/−) cells, respectively. In a combination of SP-600125 and anti-IL-8 Ab, only 22% cell death was observed in both HCT116 (Wild) (Fig. 4E1) and HCT116 (p53−/−) (Fig. 4E2) cells. The amount of cleaved PARP also showed the similar extent of cell death as shown in the MTT assay (supplemental Fig. 4C). These data suggested that by inhibiting FasL, both p53-positive and p53-negative cells show a similar extent of cell death mediated by doxorubicin.

FIGURE 4.

Effect of JNK inhibitor, anti-FasL Ab, or anti-IL-8 Ab on doxorubicin-mediated cell death in p53-positive and -negative cells. A1 and A2, HCT116 (p53−/−) and wild type cells were treated with different concentrations of JNK inhibitor (SP-600125) for 2 h and then stimulated with 1 μm doxorubicin for 24 h. After these treatments, nuclear extracts were prepared and assayed for AP-1 by gel shift assay. B1 and B2, HCT116 (p53−/−) and wild type cells were treated with 10 μm SP-600125 (B1) or 1 μg/ml anti-FasL antibody (B2) for 2 h and then treated with 1 μm doxorubicin for 72 h in triplicate. Cell viability was detected by MTT assay, and inhibition of cell viability was indicated in the figure considering untreated cell viability as 100%. C1 and D1, HCT116 (p53−/−) and wild type cells were pretreated with SP-600125, anti-IL-8 Ab, or both in combination for 2 h followed by treatment with doxorubicin (1 μm) for 24 h, the amount of FasL was detected from whole-cell extracts by Western blot (C1), and NF-AT DNA binding activity was measured from nuclear extract by gel shift assay (D1). HCT116 (p53−/−) and wild type cells were transfected with Qiagen SuperFect reagent for 3 h with plasmids for FasL or NF-AT promoter DNA that had been linked to luciferase (FasL-luciferase or NF-AT-luciferase) and GFP. After washing, cells were cultured for 12 h. The GFP-positive cells were counted, and transfection efficiency was calculated. C2 and D2, cells were pretreated with SP-600125, anti-IL-8 Ab, or both in combination for 2 h followed by doxorubicin (1 μm) for 24 h, and luciferase activity was measured and indicated as -fold of activation for FasL-dependent genes (C2) or NF-AT-dependent genes (D2). E1 and E2, HCT116 (p53−/−) and wild type cells were treated without or with 10 μm SP-600125 and 1 μg/ml anti-FasL Ab or -IL-8 Ab for 2 h and then stimulated with 1 μm doxorubicin for 72 h. Cell viability was detected by MTT assay, and inhibition of cell viability was indicated in the figure, considering untreated cell viability as 100%.

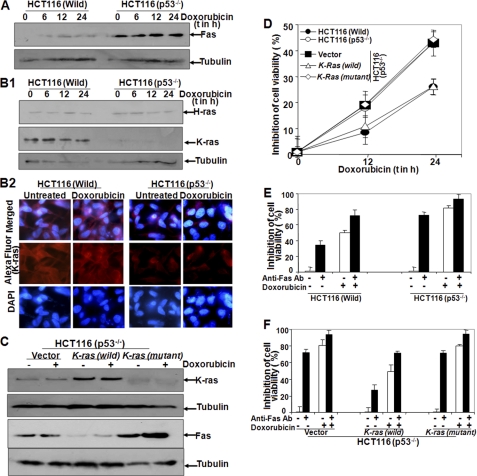

HCT116 (Wild) Cells Show High Basal Expression of K-ras, but Low Basal Expression of Fas

As FasL is expressed in both p53-positive and p53-negative cells upon doxorubicin treatment, the amount of Fas was measured to understand the differential cell death. A high basal amount of Fas was observed in HCT116 (p53−/−) cells, and doxorubicin did not alter this basal amount of Fas (Fig. 5A). The high basal amount of K-ras, but not H-ras, was observed in HCT116 (Wild) cells, as shown by Western blot (Fig. 5B1) and immunofluorescence (Fig. 5B2). Doxorubicin treatment did not alter this basal expression of K-ras. HCT116 (p53−/−) cells, transfected with vector, K-ras (wild), and K-ras (mutant) constructs were treated with doxorubicin, and the amount of Fas and K-ras was measured. In K-ras (wild)-transfected cells, the amount of K-ras was observed (Fig. 5C, upper panel). The basal amount of Fas, which was detected in vector or K-Ras (mutant) cells, was almost completely inhibited in K-ras (wild)-transfected cells (Fig. 5C, lower panel). These data suggest that K-ras interplays in the basal amount of Fas, which is shown in p53-negative cells. K-ras-transfected HCT116 (p53−/−) cells showed a similar cell death as shown in HCT116 (Wild) cells, as shown by MTT assay (Fig. 5D). Anti-Fas Ab-pretreated cells showed 38% (p < 0.001) cell death in HCT116 (Wild) cells, but 75% (p < 0.005) cell death was observed in HCT116 (p53−/−) cells (Fig. 5E). Doxorubicin further potentiated cell death in both types of cells. In HCT116 (p53−/−) cells, transfected with K-ras showed similar cell death by anti-Fas Ab and doxorubicin as shown in HCT116 (Wild) cells. HCT116 (p53−/−) cells, transfected with vector of mutant K-ras, showed almost 75% cell death by anti-Fas Ab alone and almost 80% cell death by doxorubicin treatment. Co-incubation of anti-Fas Ab and doxorubicin showed almost 95% (p < 0.01) cell death in HCT116 (p53−/−) cells, transfected with vector or mutant K-ras (Fig. 5F). These data suggest that K-ras regulates the expression of Fas, which helps in differential cell death mediated by doxorubicin and anti-Fas Ab in p53-positive and -negative cells.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of doxorubicin in expression of K-ras and Fas on p53-positive and -negative cells. A and B1, HCT116 (p53−/−) and wild type cells were treated with 1 μm doxorubicin for different times, and whole-cell extracts were used to detect Fas (A) and H-ras and K-ras (B1) by Western blot analysis. Blots were reprobed for tubulin. B2, both HCT116 (p53−/−) and wild type cells were treated with 1 μm doxorubicin for 24 h, and then cells were used to detect K-ras by anti-K-ras Ab conjugated with Alexa Fluor 594 by immunofluorescence microscope. HCT116 p53 (p53−/−) cells were transfected with vector, K-ras (wild), or K-ras (mutant), and GFP constructs were transfected with Qiagen SuperFect reagent for 3 h. After transfection, cells were washed and cultured for 12 h. GFP-positive cells were counted under a fluorescence microscope, and transfection efficiency was calculated. C, cells were treated with doxorubicin (1 μm) for 24 h, and then the amounts of K-ras and Fas were measured by Western blot. Transfected cells, HCT116 (p53−/−), and HCT116 (Wild) cells were treated with doxorubicin (1 μm) for 12 and 24 h, and cell viability was assayed by MTT assay. D, results are indicated as inhibition of cell viability in percentage. HCT116 (p53−/−) and wild type cells were incubated with 1 μg/ml anti-Fas Ab for 2 h and then treated with doxorubicin (1 μm) for 72 h. Cell viability was assayed by MTT assay. E, results are indicated as inhibition of cell viability in percentage. HCT116 (p53−/−) cells were transfected with vector, K-ras (wild), or K-ras (mutant) for 3 h, and GFP constructs were transfected with Qiagen SuperFect reagent for 3 h. After transfection, cells were washed and cultured for 12 h. Cells were incubated with 1 μg/ml anti-Fas Ab for 2 h and then treated with doxorubicin (1 μm) for 72 h. F, cell viability was assayed by the MTT assay and indicated as inhibition of cell viability in percentage.

DISCUSSION

Doxorubicin is a widely used chemotherapeutic drug for treating breast cancer and many other tumors. Doxorubicin treatment often causes DNA damage and oxidative stress that leads to change in mitochondrial membrane potential followed by cell death (3, 4). DNA damage often leads to activation of p53, which is a well known tumor suppressor. In many tumor cells, the p53 is non-functional either by deletion or by mutation of it. Doxorubicin is a very potent chemotherapeutic drug against breast tumor. MCF-7 cells have wild type p53 that might be a target of doxorubicin, although p53-mutated breast tumor cells such as SKBr3 or MDA-MB-231 are also targeted by doxorubicin more aggressively for cell death. However, the role of p53 in tumor biology is very confusing. Chemotherapeutic drugs are effective even in the absence of p53. We have found that in p53-positive cells, doxorubicin-mediated cell death is slower and less potent than in p53 down-regulated cells, which is supported by a number of evidences such as conversion of MTT dye, nuclear and DNA fragmentation, LIVE/DEAD assay, caspase activation, and caspase-dependent cellular protein fragmentation. In p53-positive cells, activation of p53 and its dependent genes is observed, which always induces cell cycle arrest and thereby apoptosis. Although in p53-positive cells, apoptosis is observed, when compared with p53-negative cells, the apoptosis is 20–25% less at any time of doxorubicin treatment. It is surprising that p53-negative cells lack several p53-mediated genes that arrest cell cycle; still, doxorubicin-mediated cell death is much efficient. It is obvious that the unanswered question is that p53-mediated cell death might be proceeding through cell cycle arrest, but in p53-negative cells, the cell death may be independent of cell cycle arrest, and this needs to be studied further.

The p53 transcription factor activates several genes that usually help in cell cycle arrest. Some of the genes expressed by p53 are prosurvival genes such as Cox2, DDR2, EGF, etc. (29, 30). It has been reported that myosin VI, a p53-dependent gene that is involved in the endocytosis pathway, inhibits DNA damage in a p53-dependent manner (31). The high amount of p53 is also regulated by MDM2 (murine double mutant 2) through proteasomal degradation (32). However, all these reports suggest the down-regulation of p53. Although we did not observe the decrease in p53 activation, which was shown either by DNA binding activity or by p53-dependent gene expression, MDM2 helps proteasome-mediated degradation of p53. As we did not observe the decrease in the amount of p53 as shown by Western blot, the role of MDM2 in repression of doxorubicin-mediated cell death should be ruled out. It is important to look for the molecules that interact with p53 for its repression.

Doxorubicin increased activities of caspases. Recruitment of proteins containing death domain is a prerequisite for activation of caspases. Recruitment of these proteins is often preceded by interaction of death ligands such as FasL, TNF, and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) with their respective receptors. Several studies have shown that commonly used chemotherapeutic drugs can stimulate the expression of NF-κB-dependent inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF, IL-1, FGF, G-CSF, VEGF, and IL-6 (33, 34). Activation of NF-κB and AP-1 is redox-sensitive (35, 36). Doxorubicin is known to increase reactive oxygen species by reacting with cellular iron (37), and this may cause the activation of NF-κB and AP-1. Doxorubicin treatment increased DNA binding to AP-1 and the amount of FasL irrespective of the amount of p53. FasL expression is AP-1-dependent. Surprisingly, the inhibition of AP-1 DNA binding did not block complete inhibition of FasL expression by doxorubicin treatment. Doxorubicin treatment was found to enhance a biphasic activation of NF-κB, further supporting our previous observation (17). It has been reported that doxorubicin-mediated first phase activation of NF-κB leads to expression of FasL through a sequential process: NF-κB-dependent IL-8 expression, IL-8-mediated increase in intracellular free Ca2+, Ca2+-dependent calcineurin activation, calcineurin-mediated dephosphorylation of NF-AT, nuclear translocation of NF-AT, and NF-AT-dependent FasL expression (17). Suppression of FasL expression mediated by NF-κB (via IL-8) and AP-1 inhibits cell death almost 60% in p53-positive cells and 75% in p53-negative cells. Doxorubicin-mediated additive cell death (20–25%) in p53-negative cells is completely inhibited by suppression of FasL. These data suggest that FasL-mediated cell death interplays in aggressive cell death in p53-negative cells induced by doxorubicin. Although FasL expression is observed in both p53-positive and p53-negative cells, the FasL-mediated response is still the determining factor for aggressive cell death in p53-negative cells. FasL interacts with its specific cell surface receptor Fas/CD95 to induce cell death via caspase activation. To our surprise, higher basal expression of Fas is observed in p53-negative cells when compared with p53-positive cells. The p53-negative cells showed more cell death upon exposure to anti-Fas Ab. These data further support that the expression of Fas in these cells is higher resulting in pronounced cell death, which is further potentiated by doxorubicin treatment. Mutant p53 has been shown to suppress Fas expression (38), which may not be true in the case of HCT116 cells where we are not detecting the basal expression of Fas. We have also noticed that p53-positive cells have a high basal expression of K-ras. Ras family proteins are usually an activator of cell proliferation, but we are getting the opposite effect in K-ras, which is suppressing p53-mediated cell death in doxorubicin-treated cells. Basal K-ras expression is shown to be absent in colon cancer cells (9), which is supporting out observation that HCT116 cells have no basal expression of K-ras, whereas p53 overexpressed HCT116 cells show high basal expression of K-ras, which further supports that Ras is one of the p53-dependent genes (39). It has been reported that K-ras suppresses p53 through stabilization of Snail protein, which directly binds with p53, via expression of ataxia telangiectasia-mutated and Rad3-related proteins (40). How p53 regulates K-ras expression needs to be studied further. The Ras family of oncogenes, especially H-ras, has been shown to down-regulate Fas via the PI3 kinase pathway and thus execute an antiapoptotic effect (36). It has been reported that sustained activation of the Ras/Raf/MAPK cascade has been observed in activation of p53 (41). The possible role of basal expressed K-ras might be decreasing the amount of Fas in p53-positive cells.

Considering the usefulness of doxorubicin in treating different tumors, especially breast cancer, the detailed mechanism of action would help to design the chemotherapeutic drugs for effective therapy especially for combination therapy and drug-resistance. We have detected the role of p53 in doxorubicin-mediated cell death in different tumor cells. How p53 interplays in doxorubicin-mediated cell death involving FasL expression might help to detect the role of these molecules in doxorubicin drug resistance as p53 exerts its regulated cell death effect in p53-positive cells. Thus, this study would be useful to understand the role of p53 to regulate cell death where K-ras puts a brake and down-regulates Fas expression, thereby slowing down apoptosis in p53-positive cells.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by a grant from the Department of Science and Technology (DST), Government of India, and a core grant from the Centre for DNA Fingerprinting and Diagnostics (CDFD). This work was also supported by Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Government of India fellowships (to C. G., S. M., and M. T.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–4.

- NF-AT

- nuclear factor of activated T-cells

- AP-1

- activator proteins 1

- FasL

- Fas ligand

- MTT

- 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiozolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide

- PARP

- poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase

- NE

- nuclear extracts

- Ab

- antibody

- pNA

- para-nitroaniline.

REFERENCES

- 1. Blum R. H., Carter S. K. (1974) Ann. Intern. Med. 80, 249–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Harris J. R., Morrow M., Bonnadona G. (1993) in Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology (De Vita V. T., Hellman S., Rosenberg S. A. eds), 4th Ed., pp. 1264–1332, Lippincott, Philadelphia, PA [Google Scholar]

- 3. L'Ecuyer T., Sanjeev S., Thomas R., Novak R., Das L., Campbell W., Heide R. V. (2006) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 291, H1273–H1280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yeh Y. C., Lai H. C., Ting C. T., Lee W. L., Wang L. C., Wang K. Y., Lai H. C., Liu T. J. (2007) Biochem. Pharmacol. 74, 969–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Downward J. (2003) Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 11–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yaswen P., Campisi J. (2007) Cell 128, 233–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ventura A., Kirsch D. G., McLaughlin M. E., Tuveson D. A., Grimm J., Lintault L., Newman J., Reczek E. E., Weissleder R., Jacks T. (2007) Nature 445, 661–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Konishi H., Konishi H., Karakas B., Abukhdeir A. M., Lauring J., Gustin J. P., Garay J. P., Konishi Y., Gallmeier E., Bachman K. E., Park B. H. (2007) Cancer Res. 67, 8460–8467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guerra C., Mijimolle N., Dhawahir A., Dubus P., Barradas M., Serrano M., Campuzano V., Barbacid M. (2003) Cancer Cell 4, 111–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lee S. H., Lee S. J., Jung Y. S., Xu Y., Kang H. S., Ha N. C., Park B. J. (2009) Neoplasia 11, 22–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Raghavendra P. B., Sreenivasan Y., Ramesh G. T., Manna S. K. (2007) Apoptosis 12, 307–318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 12. Molkentin J. D., Lu J. R., Antos C. L., Markham B., Richardson J., Robbins J., Grant S. R., Olson E. N. (1998) Cell 93, 215–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhu J., Shibasaki F., Price R., Guillemot J. C., Yano T., Dötsch V., Wagner G., Ferrara P., McKeon F. (1998) Cell 93, 851–861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Manna S. K., Gangadharan C. (2009) Mol. Immunol. 46, 1340–1350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Manna S. K., Manna P., Sarkar A. (2007) Cell Death Differ. 14, 158–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gangadharan C., Thoh M., Manna S. K. (2009) J. Cell. Biochem. 107, 203–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gangadharan C., Thoh M., Manna S. K. (2010) Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 120, 671–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Faris M., Latinis K. M., Kempiak S. J., Koretzky G. A., Nel A. (1998) Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 5414–5424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harwood F. G., Kasibhatla S., Petak I., Vernes R., Green D. R., Houghton J. A. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 10023–10029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sreenivasan Y., Sarkar A., Manna S. K. (2003) Biochem. Pharmacol. 66, 2223–2239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Manna S. K., Sreenivasan Y., Sarkar A. (2006) J. Cell. Physiol. 207, 195–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hui L., Zheng Y., Yan Y., Bargonetti J., Foster D. A. (2006) Oncogene 25, 7305–7310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tomita Y., Marchenko N., Erster S., Nemajerova A., Dehner A., Klein C., Pan H., Kessler H., Pancoska P., Moll U. M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 8600–8606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shiohara M., Akashi M., Gombart A. F., Yang R., Koeffler H. P. (1996) J. Cell. Physiol. 166, 568–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bunz F., Dutriaux A., Lengauer C., Waldman T., Zhou S., Brown J. P., Sedivy J. M., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B. (1998) Science 282, 1497–1501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thoh M., Kumar P., Nagarajaram H. A., Manna S. K. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 5888–5895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 27. Bose J. S., Gangan V., Prakash R., Jain S. K., Manna S. K. (2009) J. Med. Chem. 52, 3184–3190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Manna S. K., Babajan B., Raghavendra P. B., Raviprakash N., Sureshkumar C. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 11617–11627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fang L., Li G., Liu G., Lee S. W., Aaronson S. A. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 1931–1939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ongusaha P. P., Kim J. I., Fang L., Wong T. W., Yancopoulos G. D., Aaronson S. A., Lee S. W. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 1289–1301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jung E. J., Liu G., Zhou W., Chen X. (2006) Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 2175–2186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Manna S. K., Bose J. S., Gangan V., Raviprakash N., Navaneetha T., Raghavendra P. B., Babajan B., Kumar C. S., Jain S. K. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 22318–22327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ujhazy P., Zaleskis G., Mihich E., Ehrke M. J., Berleth E. S. (2003) Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 52, 463–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Levina V., Su Y., Nolen B., Liu X., Gordin Y., Lee M., Lokshin A., Gorelik E. (2008) Int. J. Cancer 123, 2031–2040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shimokawa I. (2004) Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 4, S149–S151 [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fischer U. M., Antonyan A., Bloch W., Mehlhorn U. (2006) Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 5, 531–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kotamraju S., Chitambar C. R., Kalivendi S. V., Joseph J., Kalyanaraman B. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 17179–17187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zalcenstein A., Stambolsky P., Weisz L., Müller M., Wallach D., Goncharov T. M., Krammer P. H., Rotter V., Oren M. (2003) Oncogene 22, 5667–5676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fleischer A., Rebollo A. (2004) FEBS Lett. 557, 283–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Peli J., Schröter M., Rudaz C., Hahne M., Meyer C., Reichmann E., Tschopp J. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 1824–1831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lee S. W., Fang L., Igarashi M., Ouchi T., Lu K. P., Aaronson S. A. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 8302–8305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.