Abstract

Myocardial perfusion is regulated by a variety of factors that influence arteriolar vasomotor tone. An understanding of the physiological and pathophysiological factors that modulate coronary blood flow provides the basis for the judicious use of medications for the treatment of patients with coronary artery disease. Vasomotor properties of the coronary circulation vary among species. This review highlights the results of recent studies that examine the mechanisms by which the human coronary microcirculation is regulated in normal and disease states, focusing on diabetes. Multiple pathways responsible for myogenic constriction and flow-mediated dilation in human coronary arterioles are addressed. The important role of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors, their interactions in mediating dilation, as well as speculation regarding the clinical significance are emphasized. Unique properties of coronary arterioles in human vs. other species are discussed.

Keywords: coronary circulation, myogenic response, flow-mediated dilation, EDHF, reactive oxygen species, diabetes, K+ channels

Introduction

Myocardial perfusion is governed by a variety of factors that act to regulate the coronary circulation both directly and indirectly. Direct influences include myogenic, endothelial, autoregulatory, and pharmacological responses. Neural, humoral, metabolic factors from underlying myocardium, and the effect of myocardial compressive forces comprise the indirect modulators of vascular resistance.

Under physiological circumstances, the conduit arteries contribute only about 7% to the overall coronary resistance while coronary arterioles (50–150 μm in diameter) are considered the primary site of flow regulation to the heart [27, 44]. In the normal heart, these resistance vessels are responsible for maintaining a high level of coronary vasomotor tone so that dilator stimuli such as adenosine or brief ischemia can elicit a three to fivefold increase in coronary flow [45]. However, with the development of coronary atherosclerosis, the most important contributor to morbidity and mortality in the world, vasodilator reserve is progressively exhausted as coronary resistance redistributes from the microcirculation toward the conduit arteries at the site(s) of stenosis. Initially myocardial perfusion is maintained through an autoregulatory reduction in arteriolar resistance, but as microvasculature tone is exhausted, vasodilator reserve is ultimately lost and myocardial underperfusion results in ischemia, angina, or infarction. Under these circumstances, other typically less prominent factors regulating coronary vascular tone exert greater influence on myocardial perfusion. For example, the renin-angiotensin system plays a minor role in mediating coronary vasomotor tone under normal circumstances. However, in ischemic conditions, this system is activated [51, 60]. There is evidence that endogenous angiotensin II levels and AT1-receptor density in the viable region of the myocardium are increased early after myocardial infarction [92, 145] suggesting an enhanced vasoconstrictor influence on the coronary vasculature. Similarly, in patients with coronary stenosis undergoing coronary revasculation or in patients with angiographically normal coronary arteries, but with risk factors, such as hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and smoking, coronary vasodilator reserve is reduced, the α-adrenergic effects induced by sympathetic activation on the coronary circulation becomes more dramatic, converting a net vasodilation to a frank vasoconstriction [9, 65] often resulting in myocardial ischemia [40, 66, 67]. These observations establish the importance of understanding the mechanism of coronary microcirculatory regulation, especially in the presence of coronary disease.

The regulation of coronary vasomotor tone, including autoregulation of coronary blood flow [150], endothelial function [2, 26], and Ca2+ and K+ channel activities associated with smooth muscle constriction and relaxation [30, 74], has been reviewed extensively in animal models. This review will highlight characteristics of the coronary microcirculation in humans, focusing on three areas: (1) vasomotor responses, including myogenic constriction, flow-mediated dilation (FMD), and pharmacological stimuli; (2) the complex role of endothelial derived modulators and their interactions in regulating vasomotor tone; and (3) the effect of disease, particularly diabetes, on coronary reactivity in humans. Concluding translational remarks will speculate as to the potential clinical importance of these basic vasoregulatory phenomena identified in the microvasculature of the human heart.

Methods for measuring vascular reactivity

Videomicroscopy

To understand the influence of physiological and pathophysiological vasomotor stimuli on the vasculature, it is important to isolate direct from indirect influences such as neurohumoral effects, myocardial compression, and myocardial release of metabolic factors. This is impossible using an intact heart, but can be achieved using the technique of videomicroscopy [86]. This technique has been refined over the years with several commercial preparations now available. The common principle behind this technique involves careful dissection of an arteriole from parenchymal tissue, mounting it between two micropipettes in a tissue chamber. The vessel is typically suffused and perfused with physiological salt solution at 37°C, maintaining intraluminal pressure at an estimated physiological level (60–80 mmHg) [27]. Changes in vessel diameter are monitored with a light microscope. Pharmacological stimuli can be added either through the lumen or to the external bathing solution. This method is commonly utilized for examining vascular reactivity in small arteries or arterioles ranging from 30–200 μm in diameter. The technique requires moderate manual dexterity and may require weeks or months to master.

Tension recording

An alternate technique monitors vascular tension using a miniaturized version of the wire myograph, a technique that has been well-established for measuring vasomotor tone in large arteries. Vessels are mounted onto two stirrups, one fixed and the other directly connected to a force transducer to assess changes in tension. This provides a continuous assessment of vascular tone in response to pharmacological stimulation. The technique can be mastered in a relatively short time by most people.

The choice of technique in part depends upon the size of the vessel and purpose of the planned study. Although both tend to provide directionally similar data, quantitative and occasionally qualitative differences in measured responses might occur. Advantages and disadvantages of each technique are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of techniques used to assess microvascular reactivity in vitro

| Videomicroscopy | Tension recording (wire myography) | |

|---|---|---|

| Smooth muscle contraction/relaxation | Isotonic | Isometric |

| Initial force setting | Lo (at an undefined L–T curve) | Lmax |

| Physiological relevance | High | Moderate |

| Ability to assess shear | Yes | No |

| Separation of luminal from abluminal application of stimuli | Yes | No |

| Vessel size | 30–250 μm | >150 μm |

| Ability to study multiple vessels simultaneously | Limited | High |

| Learning curve | Steep | Shallow |

Lo optimal length, L–T length–tension, Lmax length for developing maximum active force

Limitations of using human tissue

An important consideration in studying direct responses of the human coronary microcirculation is that ethical concerns preclude acquisition of isolated vessels from healthy subjects. Most of our understanding derives from examination of isolated vessels from patients with coronary disease, with tissue being obtained at the time of cardiopulmonary bypass, or from explanted hearts during transplantation or left ventricular assist device (LVAD) placement. The limitation of the absence of a true control group is compensated by the benefit of being able to conduct in vitro studies of directly obtained clinically relevant human tissue. The presence of disease can be an advantage since no animal model mimics the chronicity and complexity of human cardiovascular disease. To control for lack of a normal patient group, right atrial appendage can be obtained from subjects without coronary artery disease (CAD) or its risk factors who undergo bypass for valve replacement, or repair of congenital heart disease. However, the arterioles from these right atrial appendages can only serve as control for microvessel study, not for studies using conduit arteries.

Myogenic constriction

Myogenic constriction, an active change in vascular tone directionally parallel to a change in intraluminal pressure, is a key feature of several vascular beds [37]. Myogenic constriction serves to protect downstream vessels from sudden increases in arterial pressure. It is especially prominent in encapsulated organs such as brain, heart, and kidney where rapid changes in volume, and/or development of edema would have disastrous consequences. Myogenic responses are greatest in the microcirculation where resistance is most tightly controlled [28, 29]. Similar to other species, the human coronary microcirculation exhibits an active myogenic constriction in subjects with or without CAD [80, 112, 124] (Fig. 1). Substantial investigations have been conducted to identify the mechanism of myogenic constriction. The current concepts with respect to how vascular smooth muscle cells respond to increase in pressure include membrane depolarization via modulation of ion channels, molecular signaling cascades, and generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) as discussed below.

Fig. 1.

Myogenic constriction in human coronary arterioles. Constriction of atrial vessels (a) and ventricle vessels (b) occurs in response to a stepwise increase in intraluminal pressure. Data is adopted from [112] with permission

Membrane depolarization

One of the best supported hypotheses addressing the mechanism of myogenic constriction is that smooth muscle cells possess stretch-activated cation channels, which carry an inward current resulting in cell membrane depolarization during the course of myogenic vasoconstriction [109, 152]. Stretch activated channels have been found in freshly isolated and cultured smooth muscle cells [36], and in isolated small arteries [1, 33, 134]. However, direct evidence for stretch-activated channels contributing myogenic constriction is limited by lack of specific blockers and the technical constraints of patch-clamp methods. Recently, antisense oligonucleotide techniques have provided the first functional evidence that stretch-activated channels, specifically TRPC6 [50, 151] and TRPM4 [59, 131], are involved in the myogenic response in cerebral arteries of rats [41].

Calcium-activated K channels (KCa) exist virtually in every vascular bed in animals and humans. Opening of KCa channels result in a reduction of myogenic constriction, a negative feedback mechanism which limits the magnitude of the response [14]. The involvement of KCa channels in myogenic response was confirmed by the experimental observation that blockage of KCa channels with specific inhibitor, iberiotoxin, enhanced myogenic tone in rat cerebral arteries [81]. However, the role of KCa channels in modulating myogenic constriction varies depending upon vascular bed studied. Thus in contrast to the study described above, a frank reduction in active myogenic tone was observed after inhibiting KCa channels in rat mesenteric arteries [153]. Several endogenous mediators have also been proposed to be involved in myogenic constriction through regulating KCa channel activity. For instance, cytochrome P450 metabolite 20-HETE plays a significant role in the myogenic response of renal [103], cerebral [56], mesenteric [148], and skeletal muscle arterioles [52]. The mechanisms of this response may involve KCa channels, or activation of protein kinase C (PKC) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signal transduction cascades, as well as interaction with NO (for review see reference [129]). However 20-HETE does not mediate myogenic constriction in all vascular beds. Application of 17-ODYA, an inhibitor of cytochrome P450 omega hydroxylase, has little effect on myogenic constriction of human coronary arterioles, even though human coronary arterioles exhibit prominent myogenic vasoconstriction with a calculated myogenic index of −0.80 [112].

Molecular signaling cascades

PKC has been targeted by several studies to ascertain its role in the myogenic response. In human coronary arterioles, active myogenic constriction was impaired by inhibition of PKC with calphostin C and augmented by activation of PKC with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) [112]. Similar findings were also observed in rat mesenteric [154], cerebral [134] and skeletal arterioles [6]. Investigations focusing on more direct indicators of PKC activation showed an increase in generation of diacylglycerol, an endogenous activator of PKC. Elevations in transmural pressure in human coronary arterioles stimulate translocation of PKC-α to the plasma membrane, indicating activation of the kinase in response to a myogenic stimulus [39].

MAPKs are serine-threonine protein kinases that function in signal transduction cascades. The three major types of MAPK are ERK1/2, c-Jun NH2-terminal protein kinase (JNK), and p38 kinase. ERK1/2 has been implicated in several physiological processes including coronary myogenic constriction. In studies using human coronary arterioles [80], inhibition of MAPK/ERK1/2 (MEK1/2), the kinase upstream of ERK1/2, with PD98059 prevented the phosphorylation and activation of ERK1/2, and resulted in decrease in myogenic tone. Similar findings using porcine coronary arterioles were also reported by the same group [149].

Reactive oxygen species

The involvement of ROS in modulation of myogenic response has been demonstrated by several studies [82, 140]. Tail arteries isolated from mice lacking the gene coding for a NADPH oxidase subunit, specifically p47phox, showed no increase in superoxide ( ) production and myogenic vasoconstriction [124]. Myogenic response was also absent in tail arteries isolated from transgenic mice expressing the dominant-negative Rac mutant N17Rac, suggesting a role for this small GTPase [124]. This finding was complemented by a later study showing enhanced myogenic constriction in a superoxide dismutase knock-out mouse model [146]. Further mechanistic studies link the increased transmural pressure/stretch to subsequent activation of NADPH oxidase by examining the relationship between sphingosine kinase, a cell membrane fusion protein, and NADPH oxidase-dependent generation in response to elevated transmural pressure in hamster gracilis arteries [78]. Elevation of pressure stimulated the translocation of sphingosine kinase protein from the cytosol to the plasma membrane indicating enzymatic activation. The production of ROS was concurrent with sphingosine kinase translocation, which was abolished in gracilis arteries expressed with sphingosine kinase mutants. Moreover, exogenous application of sphingosine-1-phosphate also stimulated ROS generation in isolated vessels.

Most studies examining the role of ROS in myogenic vasoconstriction have been performed in animals. It is well known that human coronary vessels, especially in subjects with disease exhibit enhanced oxidant production. Testing the role of ROS in the myogenic signaling pathway in human hearts is an important area of future study.

Flow mediated dilation

One of the most important physiological stimuli for eliciting dilation is related to a change in flow through an artery or arteriole with the accompanying change in shear or drag on the endothelium. A change in wall shear stress triggers a complex signaling process that results in the release of factor(s) that traverse the basement membrane and act upon the underlying smooth muscle to induce vasodilation. The resulting vasodilation is termed FMD. It has been suggested that FMD provides continuity in the dilator response throughout a vascular bed by allowing communication between downstream resistance arterioles and upstream feeder conduit vessels. For example, exercising muscle releases vasodilator metabolites that relax the local downstream resistance arterioles, increasing tissue perfusion. The resulting increase in flow occurs in both the arterioles as well as in the upstream conduit vessels where it elicits a FMD that facilitates delivery of blood only to that segment of exercising muscle.

In most vessels including porcine [87], guinea pig coronary resistance vessels [144], human forearm [75, 95], and rat mesenteric arteries [91], NO mediates flow-dependent responses [87, 133]. In skeletal muscle arterioles, prostaglandins contribute to flow-induced dilation [83, 84]. Smooth muscle cells from rabbit aorta hyperpolarize during shear stress, probably independent of NO [72]. In rabbit ear small arteries, sympathetic innervation is critical [11].

Human coronary arterioles from subjects without CAD or its risk factors dilate to shear stress. This dilation is not altered by indomethacin, an inhibitor of cyclooxygenase, but is significantly reduced by L-NAME (Fig. 2a) [115]. In contrast, vessels from subjects with CAD show prominent FMD that is not affected by inhibiting either NO synthase or cyclooxygenase (Fig. 2b). The dilation is endothelium-dependent and is inhibited by blocking KCa channels [115], suggesting the essential role of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF). Interestingly the FMD is maintained in subjects with CAD where contribution of NO to vasodilation is limited, indicating a compensatory role of EDHF.

Fig. 2.

a NO synthesis partially contributes to flow-mediated dilation in human coronary arterioles from patients without CAD. b Inhibition of NO synthase or cyclooxygenase does not alter dilation to flow in coronary arterioles from patients with CAD. Data is adopted from [115] with permission

Role of EDHF

EDHF is traditionally invoked as mediator of vasodilation when endothelium-dependent dilation is not abrogated by inhibiting NO synthase and indomethacin. The evidence for EDHF involvement is often demonstrable only in the presence of reduced levels of nitric oxide since NO is a potent inhibitor of two EDHFs through (1) its inhibition of CYP450 [8] and production of EETs, and (2) its ability to effectively compete with SOD for superoxide, thus limiting the amount of H2O2 generation [96]. To this end, vasodilation to acetylcholine in wild-type mouse skeletal muscle depends upon endothelial release of NO [58]. The same vessel from NOSIII knockout mice also dilates to acetylcholine, but the dilation is instead due to release of EDHF [58]. The compensatory role of EDHF for loss of NO was also demonstrated in vasodilation of coronary arteries from eNOS knock out mice to hypercapnic acidosis [63], and porcine coronary arteries from hearts with left ventricular hypertrophy in response to bradykinin [5]. In some cases where loss of NO does not eliminate dilator responses, non-EDHF mechanisms may be responsible.

CAD, hypertension, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia are all conditions associated with excess ROS. As a result, NO bioavailability is reduced and NO-mediated vasodilation is impaired. This is precisely the situation where EDHF plays a more prominent role in agonist-induced vasodilation. Thus in conditions of enhanced oxidative stress where NO levels are reduced, EDHF can compensate for loss of NO-mediated vasodilation.

In humans with CAD, as described above, FMD is mediated by EDHF with no contribution from NO [115]. Similarly, dilation to bradykinin is also mediated by EDHF, and relatively independent of NO [114]. This is also true for human adipose arterioles [130]. In young people, NO was the major mediator in response to bradykinin [130]. In aged people, the generation of ROS was enhanced and the NO component was diminished in the dilation to bradykinin [130] or to flow [90]. Instead, EDHF became predominant dilator to maintain the same amount of dilation to bradykinin in aged people [130].

Nature of EDHF

There has been substantial effort at identifying EDHF. Unlike endothelium-derived relaxing factor (EDRF) which was subsequently found to be a single substance, NO, there are likely several EDHFs. Bio-assay studies using detector vessels demonstrate presence of a transferrable factor that can produce either dilation [77] or hyperpolarization [55]. Subsequent studies indicate that CYP450-derived epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs), H2O2, C-type natriuretic peptides (CNP), and anantamide, can function as EDHFs in certain vessels. In other vessels the transfer of potassium via myo-endothelial gap junctions formed by connexins is the responsible EDHF [10, 34]. Preliminary data from our laboratory indicate that potassium can hyperpolarize and dilate human coronary arterioles, however it does not appear to be responsible for dilation to any tested agonist.

EET’s are a family of CYP450 monooxygenase derivatives of arachidonic acid (AA). They include four regioisomers formed in varying concentrations depending on the specific CYP450 isoform involved and the vascular bed studied [23]. EET biosynthesis has been demonstrated by members of the CYP1A, 2B, 2C, 2D, 2G, 2J, 2N, and 4A isoforms. In humans, CYP1A, 2B, 2C, 2D, 2E, 2J, 4A have been described [129]. Evidence in favor of EDHF being a metabolite of AA, produced via the cytochrome P450 epoxygenase pathway, has been obtained using bovine [22, 54], porcine [47, 49], and canine [122] arteries. The role of EETs as EDHF in human tissue varies. In subcutaneous tissue [31] and in the human forearm [46] CYP450 products are responsible for dilation after agonist stimulation, while in mesenteric vessels CYP450 metabolites do not contribute to dilation [104]. FMD in human coronary arterioles is inhibited by miconazole, a blocker of CYP450 [115]. In addition, EET’s relax arterioles and hyperpolarize smooth muscle cells by opening KCa channels [22, 57]. Similarly EET’s are responsible in part for dilation to bradykinin in human coronary arterioles as evidenced by inhibition of dilation by CYP450 blockers and EET receptor antagonists using the bioassay technique [61].

Interestingly, more than one EDHF may be responsible for dilation to a given agonist or stimulus. In the human coronary microcirculation, endothelial derived H2O2 is critical in the physiological dilation to shear stress in human coronary arterioles [100], and to bradykinin in both rats [132] and humans [7, 89]. Precedence for a role of H2O2 as an EDHF was established by Matoba et al. [105] who showed H2O2-mediated dilation to acetylcholine in mouse mesenteric arteries. The same group also identified H2O2 as an EDHF in human mesenteric microvessels exposed to bradykinin [106]. Subsequent studies using atrial coronary arterioles from patients with CAD demonstrated that shear stress elicited an endothelium-dependent vasodilation associated with a rapid increase in H2O2 generation and KCa opening [113]. Exogenous application of H2O2 elicited dilation and hyperpolarized VSMC in these cannulated vessels [113]. Evidence that H2O2 was the transferrable arises from preliminary studies using a bioassay system with two human coronary arterioles cannulated in series. Polyethylene glycol-catalase (PEG-catalase) inhibitable FMD was observed in the distal vessel when flow was applied in the direction of donor to detector and not vice versa.

The source for generation of H2O2 in response to shear stress of human coronary arterioles has been investigated. A more complex situation exists in the human coronary microcirculation than in animal models. A unique signal transduction pathway for shear-induced ROS generation has been discovered that involves the mitochondrial respiratory chain as reported by Liu et al. [100]. Inhibition of mitochondrial inner membrane complex I or III, but not IV reduces shear-mediated H2O2 formation and FMD [100] (Fig. 3). Thus the mitochondria are an integral component of the shear-induced arteriolar dilation in the human heart. However, mitochondrial ROS production involves multiple complex pathways. The role of various enzymes, electron carriers, as well as other mediators may differ depending upon the experimental conditions. For example, while inhibition of complex 1 with rotenone reduced mitochondrial ROS in intact human coronary arterioles [100] or in isolates of mitochondrial complex 1 [20], increased mitochondrial ROS was observed in isolated mitochondria [3]. It is important to note that all studies where rotenone is used to inhibit the mitochondrial electron transport chain must consider non-specific and potentially toxic effects of rotenone that might otherwise compromise mitochondrial function. Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential and respiratory capacity in state 3 and 4 would help eliminate concern over such non-specificity.

Fig. 3.

Effect of inhibition of complex I with rotenone (a), complex II with myxothiazol (b), or complex IV with cyanide (c) on flow mediated dilation in human coronary arterioles. Dilations to increasing pressure gradients are significantly reduced by rotenone or myxothiazol but not by cyanide. Data is adopted from [100] with permission

It is not known how mechanical shear stress acting on the endothelial cell membrane is transduced to mitochondria, ultimately eliciting ROS production and vasodilation. Recently published work from our laboratory examined the role for cytoskeletal elements which are established candidates for transducing mechanical endothelial signals [97]. Shear activates focal adhesion kinases linked to integrins on the abluminal membrane through actin filament connections [85]. Hutcheson et al. demonstrated that shear-induced NO-mediated dilation in rabbit aorta was dependent upon intact endothelial microtubules and filaments [71]. Sun et al. [136] extended these observations to the microcirculation using rat gracilis arterioles. They showed that nocodazole or colchicine in doses that disrupt endothelial microtubules, prevented flow-induced dilation. Similar to animal models, flow-induced mitochondrial ROS generation and vasodilation in human coronary arterioles is blocked by disrupting endothelial F-actin and microtubules with cytochalasin D and nocodazole, respectively, indicating that cytoskeletal elements are a critical component of the signaling mechanism linking endothelial shear and mitochondrial release of ROS in the human coronary microcirculation [97].

Interaction among EDHFs

Less is known about interactions among EDHFs, however in the human heart where more than one EDHF is produced during shear or agonist stimulation with bradykinin, a unique interaction appears to exist. Recently, Larsen et al. demonstrated that H2O2 inhibits the production of EETs in human coronary arterioles. In this study, bradykinin elicited an endothelium-dependent dilation that was reduced by catalase but not by 14,15-epoxyeicosa-5(Z)-enoic acid (EEZE), 6-(2-propargyloxyphenyl)hexanoic acid (14–15 EEZE; an EET receptor blocker [54], sulfaphenazole a selective inhibitor of CYP450 2C9 [46], or iberiotoxin, a blocker of large conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. In the presence of catalase, the residual dilation was markedly reduced by 14–15 EEZE, sulfaphenazole, or iberiotoxin [89]. This finding suggested that bradykinin-induced release of H2O2 inhibited EET bioavailability, an interpretation that was confirmed using a bioassay preparation in which bradykinin was applied to the endothelium-intact donor vessel which elicited dilation of the downstream endothelium-denuded detector. When the donor vessel was treated with catalase alone, the dilation of the detector vessel was partially reduced, but when EEZE alone was applied to the donor, there was no effect on the dilation in the detector. However EEZE significantly inhibited detector dilation when applied in the presence of catalase [89]. These findings suggest that in the human coronary microcirculation, CYP450 epoxygenases are directly inhibited by H2O2, and this interaction may modulate vascular EET bioavailability.

To test this hypothesis directly, ROS were added to microsomes expressing CYP450 2C9 or 2J2 (two isoforms present in human heart). Hydrogen peroxide but not superoxide inhibited the generation of EETs from the microsomes. Hydrogen peroxide exerted no direct effect on EETs, as measured by HPLC. Thus bradykinin elicits release of both H2O2 and EET from human coronary arterioles. Normally in vessels from subjects with CAD, an EET component is not detected. However when H2O2 is eliminated, compensatory EET release occurs as a mechanism of the residual dilatory response. The H2O2 inhibition of EET bioavailability occurs at the level of CYP450 and not by altering the dilatory properties of EETs.

Other determinants of human coronary vasomotor tone

In addition to all established dilator mechanisms in regulation of coronary blood flow under normal and pathological circumstances as discussed above, there remains substantial variability in coronary vasomotor response in situations where intensive vasoconstriction overrides dilator response or individuals with different genetic background. For instance, a dicreased coronary blood flow was observed in patients underwent coronary angioplasty and stent implantation [12, 64, 93]. An elegant study using aspirate from stented saphenous vein aortocoronary bypass grafts to perfuse rat mesenteric arteries indicated that serotonin and thromboxane A2 are key mediators responsible for the intense constriction of coronary microvessels [93], thereby reducing coronary blood flow. In addition, other studies also reported that release of TNF-α during stent implantation also contributes to impaired dilator response in coronary microcirculation [12]. Many other factors, such as endothelial progenitor cells [38], substances released from surrounding myocardium [53], alteration of NOS gene [139], and endothelial growth factor [62], have also been reported to regulate coronary vasomotor tone.

Most recently, a large number of association studies linking a certain polymorphism with coronary vasomotor responsiveness [68]. For example, human G-protein beta3 subunit C825T polymorphism is associated with coronary artery vasoconstriction [110]. The 894T allele of a G894T polymorphism in the endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) gene is associated with decreased eNOS activity and endothelial dysfunction in patients with coronary heart disease [118]. Although causal conclusion can not be drawn from the linkage analysis, it provides important information for future physiological studies in transgenic animals, which obviously need to be confirmed again in humans.

Coronary microvascular dysfunction

It has been well documented that coronary microvascular dysfunction occurs in patients with obstructive conduit CAD [111, 128], and may also occur in other myocardial diseases, including hypertrophic [143] or dilated cardiomyopathy [110], where coronary arteries undergo structural change. In the past two decades, however, a large body of evidence indicates that abnormal coronary microvascular function accompanies certain clinical conditions in the absence of coronary artery or myocardial disease. For instance, impaired coronary microvascular function has been observed in asymptomatic smokers [69] or in patients with hypertension [42], hyperlipidemia [126, 155], metabolic syndrome [70], or diabetes [121] who have no evidence of CAD. In these patients, coronary flow reserve was largely reduced which may contribute to myocardial ischemia (see [21] for detailed review). The mechanisms responsible for the impaired vasomotor responsiveness in these conditions are complex, and involve multiple pathways and factors beyond the scope of this review. Because one of the common mechanisms, enhanced ROS production, has been identified in all of the above conditions, and since potassium channels are a critical target of vasodilator stimuli, the current review discusses the influence of ROS on K channel function, focusing on diabetes.

Diabetes and vascular reactivity

Vascular function in diabetes has been studied extensively. Enhanced oxidative stress and impaired vasomotor function have been consistently linked in animal models of diabetes and in humans with type 1 or type 2 diabetes. A direct role for hyperglycemia-induced production of ROS is implicated in the vasomotor dysfunction associated with diabetes from in vitro studies [99]. Normal artery segments incubated in high glucose buffer exhibit an antioxidant-inhibitable impairment of vasodilation not observed in arteries from the same animal exposed to normal glucose buffer. There are multiple mechanisms by which ROS impair vasodilation including reduced release of endothelium-derived dilator factors, quenching of those factors, and enhanced vascular release of constrictor substances. Direct effects on vascular smooth muscle are also important and include an inhibitory effect of ROS on K+ channels in vascular smooth muscle cells, extending the detrimental vasodilator effect of diabetes and ROS to the medial layer of the vascular wall. Although the vasomotor effects of high glucose are protean, we will focus on effects related to potassium channels which are important in eliciting dilation in the human coronary microcirculation.

KATP channels

ATP-sensitive K+ channels are present in the vasculature of most organs and participate in vasodilation to hypoxia and ischemia. A large body of literature supports an impairment of dilation to KATP channel openers aprikalim, levcromakalim or cromakalim in aorta [76], mesenteric [13] and cerebral arteries [107, 108] of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Human coronary arteriolar dilation to aprikalim, a selective KATP opener, is reduced in subjects with type 1 or type 2 diabetes and CAD compared to those with CAD but without diabetes [116]. Interestingly when stratified for other disease conditions (hypertension, heart failure) only diabetes was found to confer a reduction in dilation to KATP opening [116]. Of clinical importance, hypoxic coronary arteriolar dilation was also reduced in subjects with diabetes [116], possibly contributing to the observed greater morbidity to myocardial ischemia in subjects with diabetes. It is postulated that one of the mechanisms responsible for the impaired KATP channel function in diabetes is over-production of ROS.

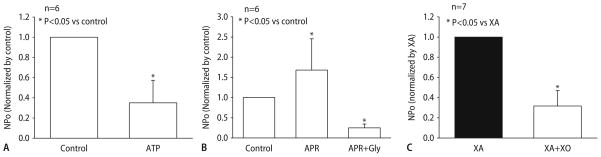

To eliminate the confounding influence from multiple radicals on vasomotor function in diabetic patients, the specific effect of on KATP channel activity was examined in isolated rat coronary arteries. As indicated in Fig. 4, dilation to aprikalim was significantly diminished by produced by the reaction of xanthine and xanthine oxidase. The impaired dilation to aprikalim can be restored by application of SOD and catalase. These functional observations were further confirmed electrophysiologically using inside-out patch clamp techniques. Openings of 20 pS channels in rat coronary myocytes were markedly reduced by 1 mM ATP (Fig. 5a). Aprikalim (10 μM) significantly augmented channel activity. The enhancement was decreased by 1 μM glibenclamide (Fig. 5b) confirming that the channels studied were KATP channels. The open state probability of KATP channels was inhibited by incubation for 20 min with xanthine and xanthine oxidase (Fig. 5c) indicating the inhibitory effect of on KATP channels. Interestingly, the effect of on KATP channel activity in cardiac myocytes is different than in the vasculature. Studies by Tokube et al. [142] reported that increases the open state probability of KATP channels in ventricular cells from guinea pigs in cell-attached and inside out patches. This effect was enhanced by ADP, and abolished by either radical scavengers or glibenclamide. This differential response may relate to the different effect of ROS on the distinct Kir and SUR subunits of the vascular and cardiac KATP channels [73]. In cardiac myocytes, increased KATP channel activity by may involve modulation of the ATP binding site of the SUR subunit of the channel [73]. In diabetes, the net effect of ROS on KATP channel activity in the heart is complex, affecting vascular and cardiac tissue differently.

Fig. 4.

Effect of superoxide on aprikalim-induced dilation of rat small coronary arteries. a Dilation to aprikalim was markedly reduced in the presence of xanthine (XA, 10−4 mol/L), xanthine oxidase (XO, 10 mU/ml), and catalase (500 U/ml) indicating an inhibitory effect of superoxide. b Reduced dilation to aprikalim can be restored by superoxide dismutase (SOD, 150 U/ml) and catalase

Fig. 5.

a Comparison of open state probability (NPo) of KATP channels in rat coronary smooth muscle cells in the absence (control) and presence of 1 mM ATP. NPo was significantly reduced by ATP. b NPo of KATP channels in response to 10 μM aprikalim and 1 μM glibenclamide in the presence of aprikalim. Aprikalim greatly increased NPo in coronary smooth muscle cells. This enhancement was inhibited by glibenclamide. c Effect of superoxide on KATP channels activities. Open state probability (NPo) of KATP channels was significantly reduced by XA and XO. XA alone had no effect on NPo

KCa channels

Unlike vascular KATP channels, KCa channels are resistant to the effects of in the human coronary microcirculation. Vasodilation of human coronary arterioles to bradykinin involves activation of KCa channels and is unaltered by treatment with a superoxide generating system [98] In isolated human coronary arteriolar smooth muscle cells, the open state probability of KCa channels was not affected by superoxide [98]. However, human coronary KCa channels do show redox sensitivity to the highly favorable reaction product of superoxide and NO; namely, peroxynitrite (ONOO−). ONOO− exhibits potent nitrosative and oxidative properties and has been demonstrated to be elevated in both patients and animals with diabetes [15, 25, 147]. ONOO− is capable of lipid peroxidation and nitration of tyrosine residues on key cellular proteins, often resulting in altered function but creating a useful marker of its presence, using immunohistochemical localization of nitrotyrosine residues on proteins [24, 156].

The role of ONOO− in modulating KCa channels in human coronary arterioles has been systematically investigated. Immunohistological evidence of nitrotyrosine residues was observed in human coronary arterioles treated with either authentic ONOO− or ONOO− generated by the combination of xanthine, xanthine oxidase, and the NO donor, sodium nitroprusside. ONOO− greatly attenuated dilation of human coronary arterioles to bradykinin [35] Using inside-out membrane patches of vascular smooth muscle cells, the open state probability of KCa was greatly diminished after exposure to ONOO− but not to decomposed ONOO−, suggesting that ONOO− inhibits KCa channel activity possibly by a direct effect. Given the important contribution of KCa channels in the dilation to EDHF, this could explain the impaired EDHF response in diabetes [48] although not all vessel beds demonstrate such impairment [43].

Kv channels

Kv channels are ubiquitous in vascular smooth muscle and contribute to resting vascular tone both in health and disease [32]. Similar to its effect on KATP channels, reduces activity of Kv channels when vessels are incubated in high glucose solutions in vitro [94, 99] and in animal models of diabetes in vivo [17, 18]. A SOD-inhibitable reduction in constriction to 4-aminopyridine (4-AP; broad spectrum inhibitor of the Kv channels), was observed in rat coronary small arteries exposed to high glucose [141] or isolated from diabetic rats [17]. In preliminary studies, the reduced 4-AP-induced constriction was also seen in human coronary arterioles from diabetic patients compared to non-diabetic patients. In separate studies, dilation to the cAMP activators, isoproterenol and forskolin, that dilate in part via opening of Kv channels, were examined [94]. Exposure to elevated levels of glucose both in vitro and in vivo inhibited coronary dilation to both isoproterenol and forskolin, which was partially restored by treatment with SOD mimetic, MnTABP [17].

In streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats, ONOO− production was enhanced in rat small coronary arteries. A significant reduction in Kv1 channel function by ONOO− was observed in diabetic coronary arteries. Ebselen, a scavenger of ONOO−, reduced nitration of Kv1 channel protein and improved Kv1 channel function [18]. However, these results derived from animal study remains to be confirmed in humans.

In summary, diabetes and hyperglycemia are associated with enhanced oxidative stress. Elevations in impair vascular Kv and KATP channel function, but exert little effect on KCa channels. On the other hand ONOO−, a product formed by reaction of and NO, inhibits both Kv and KCa channels, possibly by direct effect. Altered potassium channel behavior by ROS is a fundamental mechanism behind compromised coronary vascular function in diabetes. This knowledge might be helpful in formulating novel therapeutic approaches to improve perfusion in the diabetic heart.

Speculations on clinical relevance

Learning the mechanisms involved in human coronary microcirculatory tone is critical for understanding how blood flow to the heart is regulated since these vessels comprise the resistance portion of the circulation. Given the wide range of dilator mechanisms present among animal species, it becomes even more imperative to examine human vessels directly. Even though learning about microcirculatory regulation is important, the conditions under which abnormal control of microcirculatory tone contributes to pathology is limited. For example coronary microvascular spasm has been suggested to account for some forms of clinical myocardial ischemia [117, 137], and syndrome X is associated with reduced vasodilator reserve in the heart and periphery [19]. Additionally, microcirculatory abnormalities in the heart may play a clinically relevant role in diabetes where the coronary microcirculation has been shown to react abnormally and potentially limit tissue perfusion [79, 119]. However in most circumstances an impaired link between cardiac metabolism and perfusion originates not in the microcirculation, but in the conduit artery with a stenosis.

It may be useful to speculate as to the relevance of these findings in the microvasculature to conduit arteries, which are responsible for the bulk of cardiovascular disease in the world. The same endothelium-derived substances including nitric oxide, hydrogen peroxide, and EETs play a similar vasomotor role in both vessel segments, but each substance has a different profile in terms of smooth muscle proliferation, thrombosis, and pro-atherosclerotic potential.

Interestingly in the presence of CAD risk factors which affect the entire circulation, only conduit arteries develop atherosclerosis, arterioles are spared. This raises speculation that perhaps compounds released preferentially from the microcirculation, e.g. EDHFs, could compensate not only for the loss of NO dilation, but also for loss of NO’s antiatherosclerotic properties. To this end, EETs have been shown to be anti-inflammatory [88, 123] and anti-proliferative in smooth muscle cells [135, 138]. Thus EETs may represent a novel target for prevention of atherosclerosis if upregulated in conduit arteries.

The situation is more complex in the human heart. Both EETs and H2O2 are formed in response to agonists and shear stress. While both are potent dilators of human coronary arterioles, EETs have an antiatherosclerotic profile, while H2O2 is pro-inflammatory [102] and proliferative in smooth muscle cells [16, 120]. Perhaps the balance among endothelium-derived vasodilators dictates not only the degree and mechanism of dilation, but also the propensity for atheroproliferative transformation and impaired vasodilator reserve in the microcirculation.

Clinical studies supporting a role for EDHF in preventing atherosclerosis are sparse. However empiric data from examination of vessels used for coronary bypass grafts provide an intriguing correlative perspective. Epidemiological studies have shown that the long term patency (10 years) of internal mammary artery grafts is 90%, while that of saphenous vein grafts is only 25%. When the radial artery is used, an patency rate similar to that of IMA’s (88%) [125] is observed [127]. Many factors may influence this differential patency rate including trauma to the vessel, and resulting flow patterns after insertion, however it is also possible that differences in endothelial function among the graft types also contributes. Liu and colleagues showed that basal release of EDHF was greater in IMA than saphenous vein [101]. Studies by Archer’s laboratory have extended this observation [4]. They demonstrated that the EDHF 11,12-EET is generated to a greater extent and CYP450 is expressed in higher levels in IMA than saphenous vein segments from humans [4]. Thus the ability of the endothelium to produce EETs correlates with the graft vessel resistance to stenosis and occlusion. Future investigations should examine this hypothesis which has direct therapeutic implications.

As summarized in Fig. 6, under normal circumstance, myocardial perfusion is largely regulated by metabolic factors, myogenic tone, shear stress, and neurohumoral stimuli. Multiple pathways proposed as mechanisms for the mechanotransduction events leading to myogenic constriction include smooth muscle cell membrane depolarization, and molecular signaling cascades, including the generation of ROS. The endothelium also regulates vasomotor tone in response to pharmacological stimuli and mechanical force by release of vasodilators including NO, PGI2 and EDHF. In human conduit coronary arteries, dilation occurs through NO, whereas in the coronary arterioles, EDHF is the major dilator. The important role of EDHF manifests in disease states where NO production is reduced due to elevated levels of ROS. In this situation EDHF can compensate for loss of NO. Several EDHFs have been identified. The role of each in mediating microvascular tone in humans and other species, as well as the interactions among these dilator products require further investigation since many of these factors may have therapeutic application not only to improving myocardial perfusion, but also in preventing or treating atherosclerotic coronary vascular disease.

Fig. 6.

Schematic diagram outline the complex components of vascular regulation in human coronary microcirculation mentioned in this review

Acknowledgments

This review was supported by funding from NIH-NHLBI (R01HL067968 and R01HL080704), an American Heart Association Fellowship, and the VA Merit Review Program.

Contributor Information

Yanping Liu, National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda (MD), USA.

David D. Gutterman, Dept. of Medicine and Cardiovascular Center, The Medical College of Wisconsin, The Veterans Administration Medical Center, Milwaukee (WI), USA

References

- 1.Ahmed A, Waters CM, Leffler CW, Jaggar JH. Ionic mechanisms mediating the myogenic response in newborn porcine cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H2061–H2069. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00660.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali MH, Schumacker PT. Endothelial responses to mechanical stress: where is the mechanosensor? Crit Care Med. 2002;30:S198–S206. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200205001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreyev AY, Kushnareva YE, Starkov AA. Mitochondrial metabolism of reactive oxygen species. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2005;70:200–214. doi: 10.1007/s10541-005-0102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Archer SL, Gragasin FS, Wu X, Wang S, McMurtry S, Kim DH, Platonov M, Koshal A, Hashimoto K, Campbell WB, Falck JR, Michelakis ED. Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in human internal mammary artery is 11,12-epoxyeicosatrienoic acid and causes relaxation by activating smooth muscle BKCa channels. Circ. 2003;107:769–776. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000047278.28407.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aubin MC, Gendron ME, Lebel V, Thorin E, Tardif JC, Carrier M, Perrault LP. Alterations in the endothelial G-protein coupled receptor pathway in epicardial arteries and subendocardial arterioles in compensated left ventricular hypertrophy. Basic Res Cardiol. 2007;102:144–153. doi: 10.1007/s00395-006-0626-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bakker EN, Kerkhof CJ, Sipkema P. Signal transduction in spontaneous myogenic tone in isolated arterioles from rat skeletal muscle. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;41:229–236. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00161-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Batenburg WW, Garrelds IM, van Kats JP, Saxena PR, Danser AH. Mediators of bradykinin-induced vasorelaxation in human coronary microarteries. Hypertens. 2004;43:488–492. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000110904.95771.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bauersachs J, Popp RL, Hecker M, Sauer E, Fleming I, Busse R. Nitric oxide attenuates the release of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor. Circ. 1996;94:3341–3347. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.12.3341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baumgart D, Haude M, Gorge G, Liu F, Ge J, Grosse-Eggebrecht C, Erbel R, Heusch G. Augmented alpha-adrenergic constriction of atherosclerotic human coronary arteries. Circ. 1999;99:2090–2097. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.16.2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beny JL, Pacicca C. Bidirectional electrical communication between smooth muscle and endothelial cells in the pig coronary artery. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:H1465–H1472. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.4.H1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bevan RD, Clementson A, Joyce E, Bevan JA. Sympathetic denervation of resistance arteries increases contraction and decreases relaxation to flow. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:H490–H494. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.264.2.H490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Böse D, Leineweber K, Konorza T, Zahn A, Brocker-Preuss M, Mann K, Haude M, Erbel R, Heusch G. Release of TNF-alpha during stent implantation into saphenous vein aortocoronary bypass grafts and its relation to plaque extrusion and restenosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H2295–H2299. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01116.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bouchard JF, Dumont EC, Lamontagne D. Modification of vasodilator response in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1999;77:980–985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brayden JE, Nelson MT. Regulation of arterial tone by activation of calcium-dependent potassium channels. Science. 1992;256:532–535. doi: 10.1126/science.1373909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brodsky SV, Gealekman O, Chen J, Zhang F, Togashi N, Crabtree M, Gross SS, Nasjletti A, Goligorsky MS. Prevention and reversal of premature endothelial cell senescence and vasculopathy in obesity-induced diabetes by ebselen. Circ Res. 2004;94:377–384. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000111802.09964.EF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown MR, Miller FJ, Jr, Li WG, Ellingson AN, Mozena JD, Chatterjee P, Engelhardt JF, Zwacka RM, Oberley LW, Fang X, Spector AA, Weintraub NL. Overexpression of human catalase inhibits proliferation and promotes apoptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res. 1999;85:524–533. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.6.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bubolz AH, Li H, Wu Q, Liu Y. Enhanced oxidative stress impairs cAMP-mediated dilation by reducing Kv channel function in small coronary arteries of diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H1873–H1880. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00357.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bubolz AH, Wu Q, Larsen BT, Gutterman DD, Liu Y. Ebselen reduces nitration and restores voltage-gated potassium channel function in small coronary arteries of diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H2231–H2237. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00717.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buus NH, Bottcher M, Bottker HE, Sorensen KE, Nielsen TT, Mulvany MJ. Reduced vasodilator capacity in syndrome X related to structure and function of resistance arteries. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83:149–154. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00815-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cadenas E, Boveris A, Ragan CI, Stoppani AO. Production of superoxide radicals and hydrogen peroxide by NADH-ubiquinone reductase and ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase from beef-heart mitochondria. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1977;180:248–257. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(77)90035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Camici PG, Crea F. Coronary microvascular dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:830–840. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra061889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell WB, Gebremedhin D, Pratt PF, Harder DR. Identification of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids as endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors. Circ Res. 1996;78:415–423. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.3.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Capdevila JH, Falck JR, Estabrook RW. Cytochrome P450 and the arachidonate cascade. FASEB J. 1992;6:731–736. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.2.1537463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ceriello A. Nitrotyrosine: new findings as a marker of postprandial oxidative stress. Int J Clin Pract Suppl. 2002:51–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ceriello A, Mercuri F, Quagliaro L, Assaloni R, Motz E, Tonutti L, Taboga C. Detection of nitrotyrosine in the diabetic plasma: evidence of oxidative stress. Diabetologia. 2001;44:834–838. doi: 10.1007/s001250100529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chien S. Mechanotransduction and endothelial cell homeostasis: the wisdom of the cell. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H1209–H1224. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01047.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chilian WM. Microvascular pressures and resistances in the left ventricular subepicardium and sub-endocardium. Circ Res. 1991;69:561–570. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.3.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chilian WM, Kuo L, DeFily DV, Jones CJ, Davis MJ. Endothelial regulation of coronary microvascular tone under physiological and pathophysiological conditions. Eur Heart J. 1993;14(suppl I):55–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cipolla MJ, Gokina NI, Osol G. Pressure-induced actin polymerization in vascular smooth muscle as a mechanism underlying myogenic behavior. FASEB J. 2002;16:72–76. doi: 10.1096/cj.01-0104hyp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clapp LH, Tinker A. Potassium channels in the vasculature. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 1998;7:91–98. doi: 10.1097/00041552-199801000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coats P, Johnston F, MacDonald J, McMurray JJ, Hillier C. Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor: identification and mechanisms of action in human subcutaneous resistance arteries. Circ. 2001;103:1702–1708. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.12.1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cole WC, Clement-Chomienne O, Aiello EA. Regulation of 4-aminopyridine-sensitive, delayed rectifier K+ channels in vascular smooth muscle by phosphorylation. Biochem Cell Biol. 1996;74:439–447. doi: 10.1139/o96-048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cole WC, Plane F, Johnson R. Role of Kv1 channels in control of arterial myogenic reactivity to intraluminal pressure. Circ Res. 2005;97:e1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coleman HA, Tare M, Parkington HC. Endothelial potassium channels, endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization and the regulation of vascular tone in health and disease. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2004;31:641–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2004.04053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Csiszar A, Ungvari Z, Edwards JG, Kaminski P, Wolin MS, Koller A, Kaley G. Aging-induced phenotypic changes and oxidative stress impair coronary arteriolar function. Circ Res. 2002;90:1159–1166. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000020401.61826.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davis MJ, Donovitz JA, Hood JD. Stretch-activated single-channel and whole cell currents in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:C1083–C1088. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.262.4.C1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davis MJ, Wu X, Nurkiewicz TR, Kawasaki J, Davis GE, Hill MA, Meininger GA. Integrins and mechanotransduction of the vascular myogenic response. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H1427–H1433. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.4.H1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dernbach E, Randriamboavonjy V, Fleming I, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S, Urbich C. Impaired interaction of platelets with endothelial progenitor cells in patients with cardiovascular risk factors. Basic Res Cardiol. 2008;103:572–581. doi: 10.1007/s00395-008-0734-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dessy C, Matsuda N, Hulvershorn J, Sougnez CL, Sellke FW, Morgan KG. Evidence for involvement of the PKC-alpha isoform in myogenic contractions of the coronary microcirculation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H916–H923. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.3.H916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deussen A, Heusch G, Thamer V. Alpha–2 adrenoceptor-mediated coronary vasoconstriction persists after exhaustion of coronary dilator reserve. Eur J Pharmacol. 1985;115:147–153. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(85)90685-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Earley S, Waldron BJ, Brayden JE. Critical role for transient receptor potential channel TRPM4 in myogenic constriction of cerebral arteries. Circ Res. 2004;95:922–929. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000147311.54833.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Egashira K, Suzuki S, Hirooka Y, Kai H, Sugimachi M, Imaizumi T, Takeshita A. Impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation of large epicardial and resistance coronary arteries in patients with essential hypertension: different responses to acteylcholine and substance p. Hypertens. 1995;25:201–206. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.25.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Endo K, Abiru T, Machida H, Kasuya Y, Kamata K. Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor does not contribute to the decrease in endothelium-dependent relaxation in the aorta of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Gen Pharmacol. 1995;26:149–153. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(94)00159-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feigl EO. Coronary physiology. Physiol Rev. 1983;63:1–205. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1983.63.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feliciano L, Henning RJ. Coronary artery blood flow: physiologic and pathophysiologic regulation. Clin Cardiol. 1999;22:775–786. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960221205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fichtlscherer S, Dimmeler S, Breuer S, Busse R, Zeiher AM, Fleming I. Inhibition of cytochrome P450 2C9 improves endothelium-dependent, nitric oxide-mediated vasodilatation in patients with coronary artery disease. Circ. 2004;109:178–183. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000105763.51286.7F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fisslthaler B, Popp R, Kiss L, Potente M, Harder DR, Fleming I, Busse R. Cytochrome P450 2C is an EDHF synthase in coronary arteries. Nature. 1999;401:493–497. doi: 10.1038/46816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fitzgerald SM, Kemp-Harper BK, Parkington HC, Head GA, Evans RG. Endothelial dysfunction and arterial pressure regulation during early diabetes in mice: roles for nitric oxide and endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R707–R713. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00807.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fleming I, Fisslthaler B, Michaelis UR, Kiss L, Popp R, Busse R. The coronary endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) stimulates multiple signalling pathways and proliferation in vascular cells. Pflugers Arch. 2001;442:511–518. doi: 10.1007/s004240100565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Folgering JH, Sharif-Naeini R, Dedman A, Patel A, Delmas P, Honore E. Molecular basis of the mammalian pressure-sensitive ion channels: Focus on vascular mechanotransduction. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2008;97:180–195. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Francis GS. Pathophysiology of chronic heart failure. Am J Med. 2001;110(suppl 7A):37S–46S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00385-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Frisbee JC, Roman RJ, Falck JR, Krishna UM, Lombard JH. 20-HETE contributes to myogenic activation of skeletal muscle resistance arteries in Brown Norway and Sprague-Dawley rats. Microcirculation. 2001;8:45–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Garcia SC, Pomblum V, Gams E, Langenbach MR, Schipke JD. Independency of myocardial stunning of endothelial stunning? Basic Res Cardiol. 2007;102:359–367. doi: 10.1007/s00395-007-0657-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gauthier KM, Deeter C, Krishna UM, Reddy YK, Bondlela M, Falck JR, Campbell WB. 14,15-Epoxyeicosa–5(Z)-enoic acid: a selective epoxyeicosatrienoic acid antagonist that inhibits endothelium-dependent hyperpolarization and relaxation in coronary arteries. Circ Res. 2002;90:1028–1036. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000018162.87285.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gebremedhin D, Harder DR, Pratt PF, Campbell WB. Bioassay of an endothelium-derived hyperpolaraizing factor from bovine coronary arteries:role of a cytochrome P450 metabolite. J Vasc Res. 1998;35:274–284. doi: 10.1159/000025594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gebremedhin D, Lange AR, Lowry TF, Taheri MR, Birks EK, Hudetz AG, Narayanan J, Falck JR, Okamoto H, Roman RJ, Nithipatikom K, Campbell WB, Harder DR. Production of 20-HETE and its role in autoregulation of cerebral blood flow. Circ Res. 2000;87:60–65. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gebremedhin D, Ma Y-H, Falck JR, Roman RJ, VanRollins M, Harder DR. Mechanism of action of cerebral epoxyeicosatrienoic acids on cerebral arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:H519–H525. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.2.H519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Godecke A, Decking UK, Ding Z, Hirchenhain J, Bidmon HJ, Godecke S, Schrader J. Coronary hemodynamics in endothelial NO synthase knockout mice [In Process Citation] Circ Res. 1998;82:186–194. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gottlieb P, Folgering J, Maroto R, Raso A, Wood TG, Kurosky A, Bowman C, Bichet D, Patel A, Sachs F, Martinac B, Hamill OP, Honore E. Revisiting TRPC1 and TRPC6 mechanosensitivity. Pflugers Arch. 2008;455:1097–1103. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0359-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haitsma DB, Bac D, Raja N, Boomsma F, Verdouw PD, Duncker DJ. Minimal impairment of myocardial blood flow responses to exercise in the remodeled left ventricle early after myocardial infarction, despite significant hemodynamic and neurohumoral alterations. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;52:417–428. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00426-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Harder DR, Campbell AB, Gebremedhin D, Pratt PF. Bioassay of a cytochrome P450-dependent endothelial-derived hyperpolarizing factor from bovine coronary arteries. In: Vanhoutte PM, editor. Endothelial-derived hyperpolarizing factor. Harwood; Amsterdam: 1996. pp. 73–80. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hattan N, Chilian WM, Park F, Rocic P. Restoration of coronary collateral growth in the Zucker obese rat: impact of VEGF and ecSOD. Basic Res Cardiol. 2007;102:217–223. doi: 10.1007/s00395-007-0646-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Heintz A, Damm M, Brand M, Koch T, Deussen A. Coronary flow regulation in mouse heart during hypercapnic acidosis: role of NO and its compensation during eNOS impairment. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;77:188–196. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Herrmann J, Haude M, Lerman A, Schulz R, Volbracht L, Ge J, Schmermund A, Wieneke H, von Birgelen C, Eggebrecht H, Baumgart D, Heusch G, Erbel R. Abnormal coronary flow velocity reserve after coronary intervention is associated with cardiac marker elevation. Circ. 2001;103:2339–2345. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.19.2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Heusch G, Baumgart D, Camici P, Chilian W, Gregorini L, Hess O, Indolfi C, Rimoldi O. alpha-adrenergic coronary vasoconstriction and myocardial ischemia in humans. Circ. 2000;101:689–694. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.6.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Heusch G, Deussen A. The effects of cardiac sympathetic nerve stimulation on perfusion of stenotic coronary arteries in the dog. Circ Res. 1983;53:8–15. doi: 10.1161/01.res.53.1.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Heusch G, Deussen A, Thamer V. Cardiac sympathetic nerve activity and progressive vasoconstriction distal to coronary stenoses: feed-back aggravation of myocardial ischemia. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1985;13:311–326. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(85)90020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Heusch G, Erbel R, Siffert W. Genetic determinants of coronary vasomotor tone in humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H1465–H1468. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.4.H1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hirai N, Kawano H, Hirashima O, Motoyama T, Moriyama Y, Sakamoto T, Kugiyama K, Ogawa H, Nakao K, Yasue H. Insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction in smokers: effects of vitamin C. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H1172–H1178. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.3.H1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hsueh WA, Quinones MJ. Role of endothelial dysfunction in insulin resistance. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:10 J–17 J. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00611-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hutcheson IR, Griffith TM. Mechanotransduction through the endothelial cytoskeleton: mediation of flow- but not agonist-induced EDRF release. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;118:720–726. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15459.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hutcheson IR, Griffith TM. Heterogeneous populations of k+ channels mediate edrf release to flow but not agonists in rabbit aorta. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:H590–H596. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.2.H590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Inagaki N, Seino S. ATP-sensitive potassium channels: structures, functions, and pathophysiology. Jpn J Physiol. 1998;48:397–412. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.48.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jaggar JH, Wellman GC, Heppner TJ, Porter VA, Perez GJ, Gollasch M, Kleppisch T, Rubart M, Stevenson AS, Lederer WJ, Knot HJ, Bonev AD, Nelson MT. Ca2+ channels, ryanodine receptors and Ca2+-activated K+ channels: a functional unit for regulating arterial tone. Acta Physiol Scand. 1998;164:577–587. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.1998.00462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Joannides R, Haefeli WE, Linder L, Richard V, Bakkali EH, Thuillez C, Luscher TF. Nitric oxide is responsible for flow-dependent dilatation of human peripheral conduit arteries in vivo. Circ. 1995;91:1314–1319. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.5.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kamata K, Miyata N, Kasuya Y. Functional changes in potassium channels in aortas from rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Eur J Pharmacol. 1989;166:319–323. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(89)90076-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kauser K, Rubanyi GM. The NG-Nitro-L-Arginine insensitive endothelium-dependent relaxation of porcine coronary arteries is not mediated by a transferable relaxing substance. In: Vanhoutte PM, editor. Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor. Harwood; Amsterdam: 1996. pp. 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Keller M, Lidington D, Vogel L, Peter BF, Sohn HY, Pagano PJ, Pitson S, Spiegel S, Pohl U, Bolz SS. Sphingosine kinase functionally links elevated transmural pressure and increased reactive oxygen species formation in resistance arteries. FASEB J. 2006;20:702–704. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4075fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kersten JR, Brooks LA, Dellsperger KC. Impaired microvascular response to graded coronary occlusion in diabetic and hyperglycemic dogs. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:H1667–H1674. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.4.H1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Khan TA, Bianchi C, Ruel M, Voisine P, Li J, Liddicoat JR, Sellke FW. Mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibition and cardioplegia-cardiopulmonary bypass reduce coronary myogenic tone. Circ. 2003;108(Suppl 1):II348–II353. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000087652.93751.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Knot HJ, Standen NB, Nelson MT. Ryanodine receptors regulate arterial diameter and wall Ca2+ in cerebral arteries of rat via Ca2+-dependent K+ channels. J Physiol. 1998;508 (Pt 1):211–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.211br.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Koller A. Signaling pathways of mechanotransduction in arteriolar endothelium and smooth muscle cells in hypertension. Microcirculation. 2002;9:277–294. doi: 10.1038/sj.mn.7800142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Koller A, Huang A, Sun D, Kaley G. Exercise training augments flow-dependent dilation in rat skeletal muscle arterioles: role of endothelial nitric oxide and prostaglandins. Circ Res. 1995;76:544–550. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.4.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Koller A, Kaley G. Prostaglandins mediate arteriolar dilation to increased blood flow velocity in skeletal muscle microcirculation. Circ Res. 1990;67:529–534. doi: 10.1161/01.res.67.2.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Koshida R, Rocic P, Saito S, Kiyooka T, Zhang C, Chilian WM. Role of focal adhesion kinase in flow-induced dilation of coronary arterioles. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:2548–2553. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000188511.84138.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kuo L, Chilian WM, Davis MJ. Coronary arteriolar myogenic response is independent of endothelium. Circ Res. 1990;66:860–866. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.3.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kuo L, Chilian WM, Davis MJ. Interaction of pressure- and flow-induced responses in porcine coronary resistance vessels. Am J Physiol. 1991;261:H1706–H1715. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1991.261.6.H1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Larsen BT, Campbell WB, Gutterman DD. Beyond vasodilatation: non-vasomotor roles of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids in the cardiovascular system. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Larsen BT, Gutterman DD, Sato A, Toyama K, Campbell WB, Zeldin DC, Manthati VL, Falck JR, Miura H. Hydrogen peroxide inhibits cytochrome p450 epoxygenases: interaction between two endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors. Circ Res. 2008;102:59–67. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.159129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lauer T, Heiss C, Balzer J, Kehmeier E, Mangold S, Leyendecker T, Rottler J, Meyer C, Merx MW, Kelm M, Rassaf T. Age-dependent endothelial dysfunction is associated with failure to increase plasma nitrite in response to exercise. Basic Res Cardiol. 2008;103:291–297. doi: 10.1007/s00395-008-0714-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Learmont JG, Cockell AP, Knock GA, Poston L. Myogenic and flow-mediated responses in isolated mesenteric small arteries from pregnant and nonpregnant rats. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:1631–1636. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70620-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lefroy DC, Wharton J, Crake T, Knock GA, Rutherford RA, Suzuki T, Morgan K, Polak JM, Poole-Wilson PA. Regional changes in angiotensin II receptor density after experimental myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1996;28:429–440. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Leineweber K, Böse D, Vogelsang M, Haude M, Erbel R, Heusch G. Intense vasoconstriction in response to aspirate from stented saphenous vein aortocoronary bypass grafts. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:981–986. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Li H, Chai Q, Gutterman DD, Liu Y. Elevated glucose impairs cAMP-mediated dilation by reducing Kv channel activity in rat small coronary smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H1213–H1219. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00226.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lieberman EH, Gerhard MD, Uehata A, Selwyn AP, Ganz P, Yeung AC, Creager MA. Flow-induced vasodilation of the human brachial artery is impaired in patients <40 years of age with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1996;78:1210–1214. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00597-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Liu S, Beckman JS, Ku DD. Peroxynitrite, a product of superoxide and nitric oxide, produces coronary vasorelaxation in dogs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;268:1114–1121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Liu Y, Li H, Bubolz AH, Zhang DX, Gutterman DD. Endothelial cytoskeletal elements are critical for flow-mediated dilation in human coronary arterioles. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2008;46:469–478. doi: 10.1007/s11517-008-0331-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Liu Y, Terata K, Chai Q, Li H, Kleinman LH, Gutterman DD. Peroxynitrite inhibits Ca2+-activated K+ channel activity in smooth muscle of human coronary arterioles. Circ Res. 2002;91:1070–1076. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000046003.14031.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Liu Y, Terata K, Rusch NJ, Gutterman DD. High glucose impairs voltage-gated K+ channel current in rat small coronary arteries. Circ Res. 2001;89:146–152. doi: 10.1161/hh1401.093294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Liu Y, Zhao H, Li H, Kalyanaraman B, Nicolosi AC, Gutterman DD. Mitochondrial sources of H2O2 generation play a key role in flow-mediated dilation in human coronary resistance arteries. Circ Res. 2003;93:573–580. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000091261.19387.AE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Liu ZG, Ge ZD, He GW. Difference in hyperpolarizing factor-mediated hyperpolarization and nitric oxide release between human internal mammary artery and saphenous vein. Circ. 2000;102:III296–III301. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.suppl_3.iii-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Maas M, Wang R, Paddock C, Kotamraju S, Kalyanaraman B, Newman PJ, Newman DK. Reactive oxygen species induce reversible PE-CAM-1 tyrosine phosphorylation and SHP-2 binding. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H2336–H2344. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00509.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Maier KG, Roman RJ. Cytochrome P450 metabolites of arachidonic acid in the control of renal function. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2001;10:81–87. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200101000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Matoba T, Shimokawa H. Hydrogen peroxide is an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in animals and humans. J Pharmacol Sci. 2003;92:1–6. doi: 10.1254/jphs.92.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Matoba T, Shimokawa H, Morikawa K, Kubota H, Kunihiro I, Urakami-Harasawa L, Mukai Y, Hirakawa Y, Akaike T, Takeshita A. Electron spin resonance detection of hydrogen peroxide as an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in porcine coronary microvessels. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1224–1230. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000078601.79536.6C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Matoba T, Shimokawa H, Nakashima M, Hirakawa Y, Mukai Y, Hirano K, Kanaide H, Takeshita A. Hydrogen peroxide is an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1521–1530. doi: 10.1172/JCI10506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mayhan WG. Effect of diabetes mellitus on response of the basilar artery to activation of ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Brain Res. 1994;636:35–39. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mayhan WG, Faraci FM. Responses of cerebral arterioles in diabetic rats to activation of ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:H152–H157. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.1.H152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Meininger GA, Davis MJ. Cellular mechanisms involved in the vascular myogenic response. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:H647–H659. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.263.3.H647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Meirhaeghe A, Bauters C, Helbecque N, Hamon M, McFadden E, Lablanche JM, Bertrand M, Amouyel P. The human G-protein beta3 subunit C825T polymorphism is associated with coronary artery vasoconstriction. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:845–848. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Meredith IT, Yeung AC, Weidinger FF, Anderson TJ, Uehata A, Ryan TJ, Jr, Selwyn AP, Ganz P. Role of impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation in ishcemic manifestations of coronary artery disease. Circ. 1993;87(suppl V):V-56–V-66. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Miller FJ, Dellsperger KC, Gutterman DD. Myogenic vasoconstriciton of human coronary arterioles. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H257–H264. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.1.H257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Miura H, Bosnjak JJ, Ning G, Saito T, Miura M, Gutterman DD. Role for hydrogen peroxide in flow-induced dilation of human coronary arterioles. Circ Res. 2003;92:e31–e40. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000054200.44505.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Miura H, Liu Y, Gutterman DD. Human coronary arteriolar dilation to bradykinin depends on membrane hyperpolarization. Circ. 1999;99:3132–3138. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.24.3132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Miura H, Wachtel RE, Liu Y, Loberiza FR, Jr, Saito T, Miura M, Gutterman DD. Flow-induced dilation of human coronary arterioles: important role of Ca2+-activated K+ channels. Circ. 2001;103:1992–1998. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.15.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Miura H, Wachtel RE, Loberiza FR, Jr, Saito T, Miura M, Nicolosi AC, Gutterman DD. Diabetes mellitus impairs vasodilation to hypoxia in human coronary arterioles: reduced activity of ATP-sensitive potassium channels. Circ Res. 2003;92:151–158. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000052671.53256.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Murakami H, Urabe K, Nishimura M. Inappropriate microvascular constriction produced transient ST-segment elevation in patients with syndrome X. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:1287–1294. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00402-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Naber CK, Baumgart D, Altmann C, Siffert W, Erbel R, Heusch G. eNOS 894T allele and coronary blood flow at rest and during adenosine-induced hyperemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;281:H1908–H1912. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.281.5.H1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]