Abstract

Laser direct-writing provides a method to pattern living cells in vitro, to study various cell–cell interactions, and to build cellular constructs. However, the materials typically used may limit its long-term application. By utilizing gelatin coatings on the print ribbon and growth surface, we developed a new approach for laser cell printing that overcomes the limitations of Matrigel™. Gelatin is free of growth factors and extraneous matrix components that may interfere with cellular processes under investigation. Gelatin-based laser direct-write was able to successfully pattern human dermal fibroblasts with high post-transfer viability (91% ± 3%) and no observed double-strand DNA damage. As seen with atomic force microscopy, gelatin offers a unique benefit in that it is present temporarily to allow cell transfer, but melts and is removed with incubation to reveal the desired application-specific growth surface. This provides unobstructed cellular growth after printing. Monitoring cell location after transfer, we show that melting and removal of gelatin does not affect cellular placement; cells maintained registry within 5.6 ± 2.5 μm to the initial pattern. This study demonstrates the effectiveness of gelatin in laser direct-writing to create spatially precise cell patterns with the potential for applications in tissue engineering, stem cell, and cancer research.

Introduction

A current limitation of many in vitro culture studies is the inability to precisely control the spatial relationship of cells to growth surface features, such as substrate modifications, or to other cells in culture. Precise control of cell location, for example, to within 10 μm, can be used to replicate the in vivo cellular microenvironment and spatial distribution, allowing investigation of cellular interactions in vitro. By controlling the cell's location with respect to neighboring cells in culture, one can affect the mode of cellular signaling (direct cell contact, paracrine signaling, or endocrine signaling), as well as the types of cells in communication. Thus, custom in vitro co- or multicultures could be precisely designed to better understand cell–cell interactions as well as proximity-dependent cell fate decisions.

To achieve this level of precision in cellular assembly, a laser-based direct-writing technique, originally developed to print inks for passive microelectronic applications, was adapted to enable the patterning of biomaterials and living cells.1 Previously, pulsed laser printing techniques have shown great promise for printing numerous types of mammalian cells.2–19 Pulsed laser cell depositions have shown high cell viability,4,5,8,11–16 little to no DNA damage,6,16 unaltered apoptosis rates,8,16 little to no increase in heat shock protein expression,11,15 and normal cell proliferation.8,11,16

Current laser-based direct-write techniques have proven their efficacy and potential; however, many rely on commercially available basement membrane matrix, Matrigel™ (BD Biosciences, Bedford, MA). Specifically, Matrigel has been used in the direct-write process either as a coating for the print ribbon, as a long-term growth surface on the receiving substrate, or both.2–4,6–8,10–13,15,16,18 Matrigel is useful for cell transfer as it cushions the impact at the receiving substrate, provides a scaffold for patterning three-dimensional cell constructs through layering, maintains a moist microenvironment, and possesses a wide array of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins for cellular adhesion. However, despite these attributes, current laser direct-write techniques are limited in their scope and future application due to their reliance on Matrigel. The multiple intrinsic growth factor constituents of Matrigel—basic fibroblast growth factor, transforming growth factor-β, epidermal growth factor, insulin-like growth factor-1, and platelet-derived growth factor20—can potentially act as extrinsic cues confounding the cellular processes under investigation, and thus may preclude or greatly limit the utility of laser direct-writing for precise cell cultures. Moreover, Matrigel is derived from murine tumors, and significant lot-to-lot variations exist in the constituents. Even small fluctuations in growth factor constituents can have a profound influence on cellular response. Further, for some applications the presence of collagen IV, laminin, and heparan sulfate proteoglycan components21 may introduce proteins or other signals that could further limit the analysis of ECM protein production on the cellular level. Additionally, whereas Matrigel provides a scaffold for cell adhesion, its application prohibits user-prescribed growth surface coatings (e.g., a specific ECM protein) as Matrigel remains in the long-term culture. The ideal biopolymer to be used with laser direct-writing would resolve the shortcomings of Matrigel in providing repeatable surface coatings with controlled constituents, while maintaining cell viability and pattern registry, and allow for easy removal from the receiving substrate to provide unobstructed cell growth. Therefore, the objective of this study was to seek such a biopolymer to overcome the current limitations of Matrigel while maintaining the prior success of laser printing.

Gelatin is composed of acid-denatured collagen and has been used extensively for drug release and tissue engineering due to the biocompatibility, rapid biodegradability, known constituent purity, and the absence of growth factors.22–26 In the present study, gelatin was uniformly spin coated onto the print ribbon and used to partially encapsulate trypsinized cells on the ribbon, providing a laser interaction and buffer zone to protect the cells. More importantly, on the receiving substrate and long-term growth surface, the gelatin coating cushions the impact of transfer while maintaining a moist microenvironment during the printing process. Further, gelatin melts at 37°C,27 which allows it to be removed from the growth surface when placed in a standard cell culture incubator, thereby providing unobstructed cellular growth on the receiving surface. The ability to remove the gelatin layer could provide potential new applications; however, it could introduce an inherent obstacle for maintaining cell registry to the initial pattern. Therefore, the spatial registry of individual cells was monitored through microscopy and quantified to characterize the adherence to the initial pattern.

Gelatin-based laser direct-write was evaluated in this study using human dermal fibroblasts, although it can be applicable to virtually any cell type. Monitoring the location of the patterned cells on the receiving substrate after transfer showed that the temporary gelatin coating serves as an effective receiving surface, and maintains pattern registry until cell attachment. Analysis of cell viability and potential DNA damage after laser direct-writing verified the value of the gelatin coating for use on both the ribbon and receiving surfaces. Gelatin-based laser direct-write method is free of confounding extraneous growth factors, and thus can be utilized in studies involving cell types highly sensitive to external signals from ECM components and growth factors, such as cancer cells and stem cells. As such, gelatin-based laser direct-writing provides a solution for a variety of biomedical applications requiring precise cell patterning, particularly in the area of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

Materials and Methods

Laser system

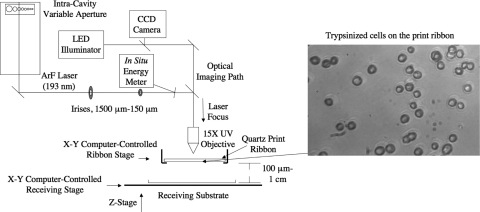

The matrix-assisted pulsed laser evaporation direct-write (MAPLE DW) system used in these experiments incorporates a pulsed excimer laser (TeoSys, Crofton, MD) operating at a wavelength of 193 nm argon-fluorine (ArF), coupled with computer-aided design (CAD)/computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) control (Fig. 1). The laser beam has a near-Gaussian distribution, a pulse width of 8 ns, and a repetition rate that can be varied from 1 up to 300 Hz. The beam is transmitted to the ribbon through an intracavity variable aperture, a series of mirrors, two irises to set the spot size, and lastly though a 15 × objective to focus the beam. An x–y motorized ribbon stage, mounted above the x–y motorized receiving stage, is controlled via a software interface that allows for user-specified motion of the ribbon, independent of the receiving substrate. Patterns used for cell deposition can be drawn in a commercial two-dimensional CAD package and converted into motion and laser-firing code. For this study, user-specified pattern arrays were written in a g-code format, which controlled the motion of the x–y motorized receiving stage. CAD/CAM control allows the user to specify the distance between transferred spots of cells within the machine code and thus prescribe the location on the receiving substrate and proximity to other cells within the user-defined pattern. Independent ribbon control allows the user to target specific cells, or groups of cells, on the print ribbon, thereby offering even greater control of cell number within the pattern. Additionally, the number of cells in each transferred spot can be modulated through adjustments in spot size and cell density. Cell density in the transferred spot can be adjusted by changing the density of trypsinized cells on the print ribbon, and by adjusting the laser beam diameter using a series of irises, the size of the transferred spot of cells (diameter ∼20–500 μm) can be prescribed. Further, the distance between the print ribbon and receiving substrate can be ranged from ∼1 cm down to ∼100 μm using a z-stage translator. An in situ energy meter is used to record the energy of every laser pulse to track shot-to-shot repeatability and ensure that the appropriate energy is delivered to the ribbon.

FIG. 1.

Schematic of the matrix-assisted pulsed laser evaporation direct-write system used to print trypsinized cells. (Inset) An image of the cells on the print ribbon highlights the optical clarity of the gelatin, which is necessary to observe cells, thereby allowing for the targeting of specific cells for transfer, and verification of proper placement on the growth surface.

The MAPLE DW system also contains an in situ charged-couple device camera that shares the optical path with the laser as it travels through the final objective. This allows the user to observe the trypsinized cells on the ribbon before transfer (Fig. 1, inset), target specific cells in real time, and verify the transfer of cells from the ribbon to the receiving dish.

Print ribbon and receiving dish preparation

Gelatin preparation

A 10 wt% concentration of gelatin was prepared for the receiving substrate by mixing 1.0 g of porcine skin-derived type A gelatin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) with 10 mL of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) and heated to obtain a homogenous mixture. A 20 wt% concentration of gelatin was created for the ribbon by mixing 4 g of gelatin with 20 mL of sterile cell culture-grade water.

Receiving dish preparation

A 100-mm-diameter Petri dish was mounted on the x–y computer-controlled motorized stage, and a fiduciary mark was laser micromachined into the bottom of the dish for use in tracking cellular pattern registry.

The marked Petri dishes were plasma cleaned for 1 min, and coated with 1.5 mL of poly-l-lysine (PLL) hydrobromide (Sigma-Aldrich). After 5 min, the excess PLL was aspirated from the dish and the dish was left to dry in a laminar flow hood for 1 h. The PLL-coated receiving dish was then mounted on a bench-top spin coater, and 1.0 mL of 10% gelatin, warmed to 60°C, was pipetted onto the receiving dish while spinning at 4000 rpm, for 25 s. The dish was placed into a refrigerator (4°C) for 5 min at which time, 10 mL of DMEM, also at 4°C, was pipetted over the dish and excess DMEM was aspirated. The receiving dish was placed into a standard cell culture incubator (37°C, 5% CO2, and 95% RH) for ∼20 min.

Ribbon preparation

A 50-mm-diameter UV transparent quartz flat disk (“ribbon”) (Edmund Optics, Barrington, NJ) was cleaned with 70% ethanol, dried, and mounted on a bench-top spin coater. Gelatin (20%) was warmed to 60°C and pipetted (1.5 mL) onto the ribbon while spinning at 2000 rpm, for 20 s. The ribbon was then placed directly into a standard cell culture incubator for 3 min.

Cell culture and direct-write

Human dermal fibroblast cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were grown in a standard cell culture incubator in 75-cm2 T-flasks (BD Biosciences) using culture medium (89.5% DMEM, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 0.5% penicillin-streptomycin). One milliliter of cells from a cell suspension (density ∼5.9 × 105 cells/mL) was pipetted into the 20% gelatin-coated ribbon, incubated for 7 min, and placed in a laminar flow hood for 4 min. The ribbon was then tilted to remove excess culture medium, blotted dry, inverted, and mounted into the ribbon stage. The laser beam diameter was set to 50 μm to achieve a fluence of ∼1.0 J/cm2. The 10% gelatin-coated receiving dish was mounted onto the receiving stage and moved to within ∼500 μm of the ribbon using the z-stage translator. Independent ribbon control allowed the user to target specific spots on the ribbon for transfer to ensure a fully populated cellular array, and the user-generated g-code controlled the receiving dish, to pattern customized arrays of cells. A 2 × 2 array program with 500-μm spacing between spots was executed, pulsing the laser once for each corresponding targeted transfer spot, depositing the cells in proximity to the fiduciary mark on the receiving dish.

After cells were transferred, from the ribbon to the receiving dish, they were imaged on an inverted optical microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) with phase contrast (10 × ). Once imaged, the receiving dish was placed in an incubator for 15 min to allow for initial cell attachment to the growth surface, at which time, 10 mL of fresh cell culture medium, warmed to 37°C, was added and the dish was returned to the incubator.

DNA damage analysis and cell viability

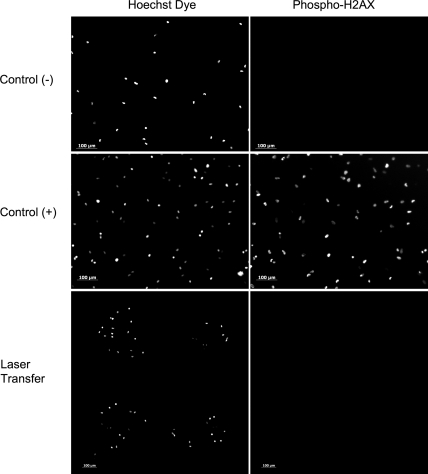

To determine whether gelatin-based laser direct-write induces double-strand DNA breaks, the presence of phosphorylated-H2AX (phospho-H2AX) was quantified immunocytochemically on cell transfer arrays (n = 4). H2AX is a histone that is phosphorylated when a double-strand DNA break occurs28–30 and aids in recruiting proteins responsible for double-strand break repair.30–32 The colocalization of nuclear stain and immunostaining for phospho-H2AX has been previously used to verify DNA damage of human fibroblasts cells when exposed to UV radiation.33 Phospho-H2AX was seen as early as 15 min after DNA damage32 and through 12 h33 depending on radiation dosage. Analysis of phospho-H2AX for this study was completed using a Cellomics® Phospho-H2AX Activation Kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) and phospho-H2AX primary antibody and Goat anti-mouse fluorescently conjugated secondary antibody. Immunostaining was completed on a negative control of nontransferred fibroblasts, a positive control of non-laser transferred fibroblasts that had been exposed for 1 h to a 25 mg/mL concentration of etoposide (Sigma Aldrich) to induce single and double-strand DNA breaks,34 and four arrays of laser printed cells. Cells were fixed 3 h after laser transfer or seeding (non-laser transferred controls) to allow for cellular adherence to the growth surfaces. Hoechst dye was used to stain for cellular DNA, to identify the cell nucleus, and to verify colocalization of DNA and phospho-H2AX. Immunofluorescent images were taken on an inverted fluorescent microscope (Carl Zeiss).

Cell viability was tracked up to 24 h post-transfer and was determined by the ability of the cells to return to their normal adherent cell morphology from their trypsinized state. A total of 369 cells from 15 separate laser transfers were analyzed for viability.

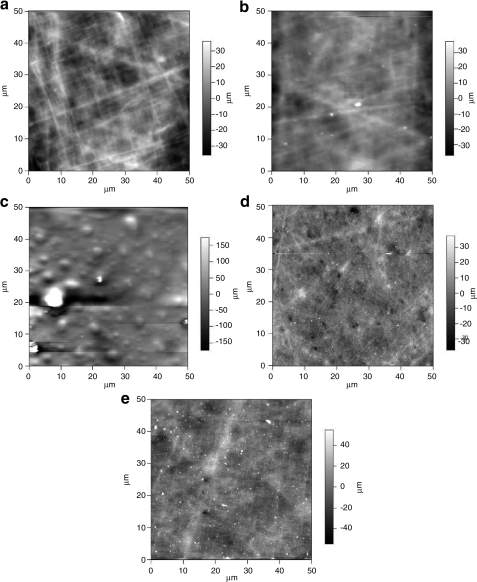

Gelatin surface analysis

To characterize the topography of the receiving dishes, they were imaged using an MFP-3D atomic force microscope (AFM; Asylum Research, Santa Barbara, CA). A receiving dish was coated with PLL and filled with the cell culture medium as a negative control. A second dish was coated in PLL, then spin coated with gelatin, filled with 4°C cell culture medium, and stored at 4°C as a positive control, and the experimental dishes were prepared as described in the receiving dish preparation, but no cells were transferred. The dishes were incubated for 15 min post-transfer, and filled with 10 mL of the warmed cell culture medium as previously prescribed, and returned to the incubator for 15 min before AFM imaging. Additional time points of 1 and 12 h of incubation were also imaged. All dishes were rinsed with ultra-pure cell culture water at 4°C before AFM imaging to remove potential artifacts generated by the proteins in the cell culture medium, then dried in a laminar flow hood, cut into sections, and mounted on glass slides. Imaging was completed in AC mode with a 50-μm scan size.

Cell pattern registry following laser direct-write

Images of the patterned cells and fiduciary mark in the receiving dishes were taken immediately after transfer (0 min), at 15 min, 30 min, and 1 h after laser direct-write. A semiautomated MATLAB® code was developed to track the trypsinized cell centroids in relation to the stationary micromachined fiduciary mark. The distance from cell centroid to fiduciary mark was calculated for each time point, then compared to the initial (0 min) time point. The absolute value of the change in distance between 0–15 min, 0–30 min, and 0–60 min indicates the distance a cell moved from its original patterned location. A total of 437 cells, from 15 laser transfers into seven separate receiving dishes, were analyzed for registry to the initial pattern. All data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of the mean. Because no outliers were present, comparisons were made between time points using two-tailed, heteroscedastic unpaired Student's t-test parametric analyses, with a level of p < 0.05 to establish statistical significance.

Cell morphology and ECM production analysis

Immunocytochemistry was performed to investigate if either the gelatin surface treatment or the laser direct-write process affects the cells' longer-term functionality (e.g., morphology and ECM production) in culture. Cells were laser direct-written into two transfer arrays (n = 2 separate receiving dishes) with 600-μm spacing between transfer spots, and cultured for 8 days. Additional cultures were carried out on fibroblasts pipetted into a PLL-coated dish and a PLL- and gelatin-coated dish (n = 1 for each) prepared as prescribed for a receiving dish to serve as nonlaser transferred controls. The cell culture medium was exchanged every 3 days. After 8 days in culture, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and treated using standard immunocytochemisty protocols and anti-human antibody: anti-40k to observe fibronectin. Cell nuclei were observed with Hoechst dye and F-actin stress fibers with phalloidin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Images were taken on an inverted fluorescent microscope (Carl Zeiss).

Results

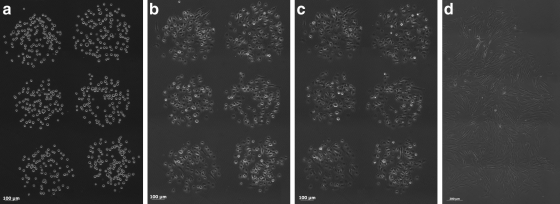

Human dermal fibroblast cells were successfully laser patterned using gelatin. Independent ribbon control allowed the user to target specific spots on the ribbon for transfer and the user-generated g-code enabled customized arrays of cells to be patterned (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Representative time course of an array of human dermal fibroblasts after gelatin-based laser direct-writing, illustrating that (a) immediately after patterning, fibroblasts remain in their trypsinized morphology, (b) at 30 min after transfer some cells begin to spread and attach, (c) at 45 min after transfer, the fibroblasts display normal adherent morphology, and (d) at 24 h post-transfer, the cells display their normal spindle-like adherent morphology (2 × 3 array, 500-μm spacing, transfer spot size ∼300 μm).

DNA damage analysis and cell viability

Arrays of laser-transferred cells demonstrated no colocalization of Hoechst dye for cellular DNA and the immunostain for phospho-H2AX, indicating the absence of double-strand DNA breaks. A negative control showed only Hoechst dye for DNA and a positive control showed the colocalization of Hoechst dye with phospho-H2AX (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Immunostaining for phosphorylated-H2AX, a histone associated with DNA double-strand breaks and DNA repair. Negative and positive controls for DNA damage are indicated along with an array of laser direct-written cells. There was no colocalized expression between Hoeschst dye for DNA and phospho-H2AX among the laser transferred cells, indicating that gelatin-based laser direct-writing did not introduce any double-strand DNA damage to fibroblasts. Phospho-H2AX, phosphorylated-H2AX.

Viability was determined by the ability of a cell to exhibit its normal adherent morphology from its trypsinized state after laser transfer. At 24 h after laser direct-write, a total of 13 cells (n = 369 cells from 15 separate laser transfers) did not exhibit normal adherent morphology and were deemed nonviable. Overall, fibroblasts maintained an average viability of 91% (±3% standard error of the mean) post-transfer at 24 h after laser direct-write.

Time course of gelatin removal

AFM analysis of surface topography indicated that the 10% gelatin coating on the receiving dish changed with respect to incubation time. Once incubated, the gelatin-layer was disrupted and surface droplet formation was observed at 15 min, an indication of gelatin melting. After 1 h of incubation, surface topography of the receiving dish was similar to the negative control (gelatin-free, PLL-only). After 12 h of incubation, there were no further changes in surface topography compared to either the PLL-control or 1-h incubated dish, suggesting that gelatin melting and removal occurred within 1 h of incubation (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Atomic force microscopic images illustrating the transient response of gelatin-coated growth surfaces with incubation duration. (a) PLL-only dish, prepared without gelatin to serve as a (–) control; (b–e) PLL-coated receiving dishes spin coated with 10% gelatin, and incubated for (b) 0 min (+) control, (c) 15 min, (d) 1 h, and (e) 12 h. Within 15 min of incubation, gelatin melting was observed, and at 1 h of incubation a similar surface topography to the negative control was seen, with no further changes observed at 12 h, suggesting an unobstructed growth surface with gelatin melting and removal within 1 h. PLL, poly-l-lysine.

Cell pattern registry following laser direct-write

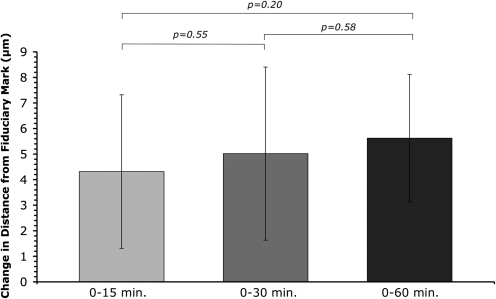

Cell tracking analysis after transfer demonstrated a high degree of pattern registry (Fig. 5). Cells were tracked immediately after transfer (0 min), and up to 60 min after transfer, which corresponds to the time course of gelatin melting and cellular attachment. After 15 min of incubation after laser transfer, cell centroid distances from the fiduciary mark differed from the initial time point by 4.3 ± 3.0 μm (mean ± standard deviation of the mean). After 30 min of incubation, cell centroid distances differed by 5.0 ± 3.4 μm from the initial time point; at 60 min the difference was 5.6 ± 2.5 μm. No significant differences were observed between any of the time points (Fig. 6).

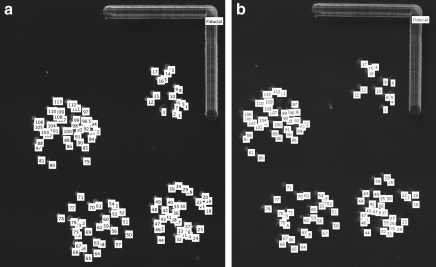

FIG. 5.

Representative image of indexed centroids of laser patterned trypsinized cells and the fiduciary marker (a) immediately after laser direct-write (0 min), and (b) after 30 min of incubation after laser direct-write. At 30 min the trypsinized cells begin to spread out and display their normal adherent morphology.

FIG. 6.

Average change in the distance from the fiduciary mark to the centroid of the trypsinized cells, comparing the initial placement immediately after transfer (0 min), to 15, 30, and 60 min of incubation time after laser cell transfer. No significant difference was seen between any incubation time points (0–15, 0–30, and 0–60 min). The maximum change in distance from initial position occurred at 60 min, indicating that, on average, cells remain within 5.6 ± 2.5 μm of their initial placement, indicating a high degree of registry to the initial pattern despite the melting and removal of gelatin from the receiving substrate. Values are given as the mean difference in distance ± standard deviation of the mean for each time point (n = 15 transfer arrays).

A small number of cells (15.6% of the 437 cells transferred) rinsed away from the transfer spots in the initial cell culture medium application or during multiple movements from the incubator to the microscope for imaging. A total of 39 cells could not be tracked from the initial time point after 15 min of incubation; 18 additional cells could not be tracked at 30 min, and 11 cells at 60 min. A transfer efficiency of 84.4% was maintained for the 15 transfer arrays at 60 min.

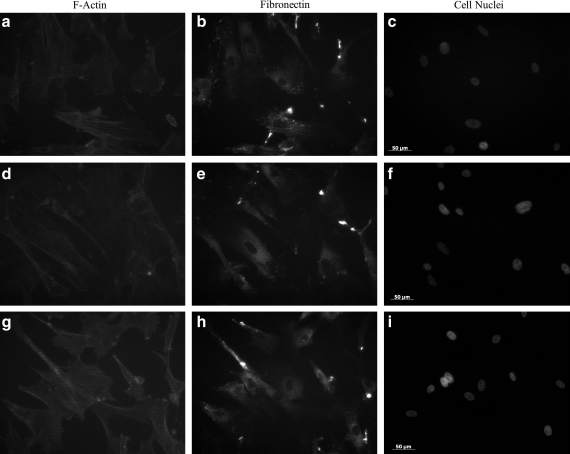

Cell morphology and fibronectin synthesis

After laser direct-write and subsequent culture for 8 days, cell morphology appeared no different from the nonlaser direct-written controls. All conditions (laser direct-written cells, and cells pipetted on controls consisting of both a PLL-only dish and a PLL-gelatin receiving dish) presented elongated and spread cell morphology with pronounced F-actin stress fibers (Fig. 7). Long-term cell functionality was demonstrated with antibody staining for fibronectin, which showed similar structure and amounts of ECM protein synthesis across all conditions (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Representative immunofluorescence images (20 × ) of fibroblasts after 8 days in culture. (a–c) Nonlaser transfer control in a PLL-only dish without gelatin, (d–f) nonlaser transfer control in a PLL- and gelatin-coated receiving dish, and (g–i) laser direct-written cells. Cell morphology, as observed with phalloidin for F-actin stress fibers (a, d, g) and Hoechst dye for cell nuclei (c, f, i), appeared similar between all conditions. In addition, as observed with antibody staining (b, e, h), the synthesis of fibronectin by the laser direct-written cells appeared unaltered from the pipetted controls, thereby indicating that the long-term functionality of the cells is preserved in gelatin-based laser direct-writing.

Discussion

Laser direct-writing is a powerful tool for the precise patterning of cells to investigate cell-to-cell interactions and responses with respect to spatial cues, and for rapidly building complex cellular constructs. However, the reliance of this technique on Matrigel, used on the print ribbon and/or receiving substrate, introduces growth factors and ECM constituents that can influence cellular growth and differentiation post-transfer, which precludes or confounds its application, particularly with sensitive cell types. Further, Matrigel limits the potential of laser direct-writing for in vivo human tissue engineering applications in that Matrigel will not receive FDA approval in the foreseeable future, due to its mouse Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm tumor origin21 and immunogenicity.35,36

To overcome these limitations, this study detailed a new gelatin-based laser direct-write method, developed to precisely pattern viable mammalian cells, in a completely Matrigel-free manner, using human dermal fibroblasts. This technique maintained high cell viability after transfer, and exhibited no evidence of double-strand DNA breaks, thereby demonstrating the nondetrimental nature of the laser-transfer process to the cells. Further, this method showed a high degree of cell registry on the receiving substrate. Registry to the initial pattern after 1 h of incubation was maintained to within the diameter of a cell (5.6 ± 2.5 μm), despite the melting and removal of the temporary gelatin layer from the growth surface.

This melting and subsequent removal of the gelatin from the receiving substrate can be utilized to provide a homogeneous growth surface that allows for normal cellular interactions and growth, uninhibited by surface treatments. This ability to pattern cells on a uniform surface is unique to laser printing as compared to other 2-D patterning techniques, such as photolithography37 or micropatterning with stencils,38 that rely on specific cellular adhesion sites that may restrict normal cellular growth and interactions. On the receiving dish, the gelatin coating melted at 37°C and was removed in the course of 1 h of incubation, leaving the desired growth surface (e.g., tissue culture plastic, PLL-coated culture plastic, user- and application-specific culture surfaces, or other ECM protein coatings), further ensuring that the function of gelatin is only transient, and thus greatly reducing any unintended effect it may have on normal cellular proliferation.

In the original Matrigel-based MAPLE DW technique, to load the print ribbon with cells, the trypsinized cells must begin to form initial attachments through cellular adhesion to the Matrigel coating on the ribbon. Thus, the cells are no longer fully trypsinized, and the focal adhesions that adhere the cells to the print ribbon may be disrupted or damaged during the transfer process. Rather than allowing the cells to spread and loosely attach to the ribbon, we exploit the slow melting of gelatin to partially encapsulate the trypsinized cells in the print ribbon's gelatin coating. This partial encapsulation of cells on the ribbon represents a fundamental change from the original MAPLE DW technique. Since the trypsinized state of the cells is maintained during printing, the cells are balled-up rather than spread out and attached, and no focal adhesions will be disrupted or damaged during laser transfer. Further, this technique can be applied to virtually any type of cell. Thus, single heterogeneous ribbons of multiple cell types can be prepared, thereby making possible the rapid printing of multiple cell types.

An unexpected advantage of the gelatin for the print ribbon was its optical clarity, which allowed for observation of both the target location on the receiving dish as well as the cells on the print ribbon. Additionally, the firm cell–ribbon attachment enables the targeting of specific cells for transfer, which cannot be achieved with other biological laser printing techniques in which cells are suspended and free floating on the print ribbon in a combination of cell culture medium and glycerol.10,11,14,15 The coupling of optical clarity and firm cell attachment on the ribbon provides unprecedented user control and selective cell targeting.

Cell centroid location tracking showed that trypsinized fibroblast cells remained in their specified locations even as the fresh growth medium was added following laser direct-write and the gelatin melted. The high degree of registry (5.6 ± 2.5 μm at 60 min post-transfer) to the initial pattern demonstrates the precision necessary to fabricate cellular constructs for in-depth investigations of cellular behavior and interactions. Although labor intensive, in situ cell tracking through 24 h post-transfer avoided having to fix and stain cells, which would have offered only representative temporal snapshots. Similarly, the in situ viability analysis, used to verify the passivity of the gelatin-based MAPLE DW transfer process, granted continuous observation and analysis over 24 h. This provides a conservative measure of cell viability, and avoids the use of live–dead staining, which can overestimate the viability, as dead cells may inadvertently be rinsed away while live cells remain adherent.

Phospho-H2AX allowed DNA damage analysis to be conducted on transfer conditions that would exactly match transfer conditions used for virtually any other laser-based cell patterning application. Although comet assays can quantify the amount of DNA damage, they require gel electrophoresis, which greatly limits, if not precludes, the investigation of DNA damage while maintaining the intended cellular pattern and transfer conditions. The ability of phospho-H2AX immunocytochemistry to assay cells while in their pattern arrays enables the analysis of DNA damage without compromising or sacrificing the structural information of the culture. Future studies can therefore investigate the spatial distribution of DNA damage.

Long-term cell functionality was verified with antibody staining for the synthesis of the ECM protein, fibronectin, in which laser-transferred cells showed no difference from pipetted (nonlaser transfer) controls. Within these controls, cells grown on receiving dishes with 10% gelatin coatings exhibited similar cell morphology and long-term cellular protein synthesis as those without gelatin. These findings suggest that neither the laser transfer process nor the 10% gelatin coating on the receiving dish had a negative influence on the cells' behavior in culture, thereby indicating that the long-term functionality of the cells is maintained in gelatin-based laser direct-writing.

The results presented herein demonstrate that gelatin-based MAPLE DW is an improvement over previous materials used for conducting in-depth investigations of cellular interactions based on spatial proximity, composition, and geometric location that are devoid of the influence of extraneous ECM proteins or growth factors. Our future applications of gelatin-based laser direct-writing will investigate the spatial dependence of cells in culture on ECM protein production, as well as the microenvironmental factors that affect stem cell differentiation. The ability to pattern cells and have control over growth substrate constituents without introducing extraneous growth factors enables future studies involving sensitive cell types, and for investigating the effect of spatial patterning on cellular growth factor secretion and cellular protein production. Gelatin-based laser direct-writing is a powerful approach in terms of precision, customization, and reproducibility. Through this relatively simple change to the MAPLE DW process, the utility of laser cell patterning has expanded, and laser direct-writing can play a more definitive role in future investigations in basic cell biology, as well as applications in tissue engineering, cancer, and regenerative medicine research.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Chris Bjornsson, Ph.D., and Gaurav Jain, M.S., of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute for their assistance with AFM imaging, as well as Livingston Van de Water, Ph.D., Courtney Betts, M.S., and Paula McKeown-Longo, Ph.D., of Albany Medical College for their assistance and generous gifts of fibronectin antibody (anti-40k), phalloidin, and Hoechst dye.

This study has been partially supported by the National Institutes of Health (1R56DK088217-01) and internal start-up funds at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Schiele N.R. Corr D.T. Huang Y. Raof Abdul N. Xie Y. Chrisey D.B. Laser-based direct-write techniques for cell printing. Biofabrication. 2010;2:032001. doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/2/3/032001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiele N.R. Koppes R.A. Corr D.T. Ellison K.S. Thompson D.M. Ligon L.A. Lippert T.K.M. Chrisey D.B. Laser direct writing of combinatorial libraries of idealized cellular constructs: biomedical applications. Appl Surface Sci. 2009;255:5444. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kattamis N.T. Purnick P.E. Weiss R. Arnold C.B. Thick film laser induced forward transfer for deposition of thermally and mechanically sensitive materials. Appl Phys Lett. 2007;91:171120. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barron J.A. Ringeisen B.R. Kim H.S. Spargo B.J. Chrisey D.B. Application of laser printing to mammalian cells. Thin Solid Films. 2004;453:383. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doraiswamy A. Narayan R.J. Harris M.L. Qadri S.B. Modi R. Chrisey D.B. Laser microfabrication of hydroxyapatite-osteoblast-like cell composites. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;80:635. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ringeisen B.R. Kim H. Barron J.A. Krizman D.B. Chrisey D.B. Jackman S. Auyeung R.Y.C. Spargo B.J. Laser printing of pluripotent embryonal carcinoma cells. Tissue Eng. 2004;10:483. doi: 10.1089/107632704323061843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doraiswamy A. Narayan R.J. Lippert T. Urech L. Wokaun A. Nagel M. Hopp B. Dinescu M. Modi R. Auyeung R.C.Y. Chrisey D.B. Excimer laser forward transfer of mammalian cells using a novel triazene absorbing layer. Appl Surface Sci. 2006;252:4743. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patz T.M. Doraiswamy A. Narayan R.J. He W. Zhong Y. Bellamkonda R. Modi R. Chrisey D.B. Three-dimensional direct writing of B35 neuronal cells. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2006;78:124. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu P.K. Ringeisen B.R. Callahan J. Brooks M. Bubb D.M. Wu H.D. Pique A. Spargo B. McGill R.A. Chrisey D.B. The deposition, structure, pattern deposition, and activity of biomaterial thin-films by matrix-assisted pulsed-laser evaporation (MAPLE) and MAPLE direct write. Thin Solid Films. 2001;398:607. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barron J.A. Spargo B.J. Ringeisen B.R. Biological laser printing of three dimensional cellular structures. Appl Phys Mater Sci Process. 2004;79:1027. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barron J.A. Krizman D.B. Ringeisen B.R. Laser printing of single cells: statistical analysis, cell viability, and stress. Ann Biomed Eng. 2005;33:121. doi: 10.1007/s10439-005-8971-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barron J.A. Wu P. Ladouceur H.D. Ringeisen B.R. Biological laser printing: a novel technique for creating heterogeneous 3-dimensional cell patterns. Biomed Microdevices. 2004;6:139. doi: 10.1023/b:bmmd.0000031751.67267.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Othon C.M. Wu X.J. Anders J.J. Ringeisen B.R. Single-cell printing to form three-dimensional lines of olfactory ensheathing cells. Biomed Mater. 2008;3:034101. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/3/3/034101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guillemot F. Souquet A. Catros S. Guillotin B. Lopez J. Faucon M. Pippenger B. Bareille R. Remy M. Bellance S. Chabassier P. Fricain J.C. Amedee J. High-throughput laser printing of cells and biomaterials for tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:2494. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen C.Y. Barron J.A. Ringeisen B.R. Cell patterning without chemical surface modification: cell-cell interactions between printed bovine aortic endothelial cells (BAEC) on a homogeneous cell-adherent hydrogel. Appl Surface Sci. 2006;252:8641. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koch L. Kuhn S. Sorg H. Gruene M. Schlie S. Gaebel R. Polchow B. Reimers K. Stoelting S. Ma N. Vogt P. Steinhoff G. Chichkov B.N. Laser printing of skin cells and human stem cells. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2009 doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2009.0397. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hopp B. Smausz T. Kresz N. Barna N. Bor Z. Kolozsvari L. Chrisey D.B. Szabo A. Nogradi A. Survival and proliferative ability of various living cell types after laser-induced forward transfer. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:1817. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu P.K. Ringeisen B.R. Development of human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVEC) and human umbilical vein smooth muscle cell (HUVSMC) branch/stem structures on hydrogel layers via biological laser printing (BioLP) Biofabrication. 2010;2:014111. doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/2/1/014111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ovsianikov A. Gruene M. Pflaum M. Koch L. Maiorana F. Wilhelmi M. Haverich A. Chichkov B. Laser printing of cells into 3D scaffolds. Biofabrication. 2010;2:014104. doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/2/1/014104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vukicevic S. Kleinman H.K. Luyten F.P. Roberts A.B. Roche N.S. Reddi A.H. Identification of multiple active growth factors in basement membrane matrigel suggests caution in interpretation of cellular activity related to extracellular matrix components. Exp Cell Res. 1992;202:1. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(92)90397-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kleinman H.K. McGarvey M.L. Liotta L.A. Robey P.G. Tryggvason K. Martin G.R. Isolation and characterization of type-IV procollagen, laminin, and heparan-sulfate proteoglycan from the EHS sarcoma. Biochemistry. 1982;21:6188. doi: 10.1021/bi00267a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y.Z. Venugopal J. Huang Z.M. Lim C.T. Ramakrishna S. Crosslinking of the electrospun gelatin nanofibers. Polymer. 2006;47:2911. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young S. Wong M. Tabata Y. Mikos A.G. Gelatin as a delivery vehicle for the controlled release of bioactive molecules. J Control Rel. 2005;109:256. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tabata Y. Ikada Y. Protein release from gelatin matrices. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 1998;31:287. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(97)00125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sisson K. Zhang C. Farach-Carson M.C. Chase D.B. Rabolt J.F. Evaluation of Cross-Linking Methods for Electrospun Gelatin on Cell Growth and Viability. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:1675. doi: 10.1021/bm900036s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lai J.Y. Lin P.K. Hsiue G.H. Cheng H.Y. Huang S.J. Li Y.T. Low bloom strength gelatin as a carrier for potential use in retinal sheet encapsulation and transplantation. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:310. doi: 10.1021/bm801039n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang L.J. Lin W.Z. Yao T.J. Tai Y.C. Photo-patternable gelatin as protection layers in low-temperature surface micromachinings. Sensors and Actuators. Physical. 2003;103:284. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rogakou E.P. Pilch D.R. Orr A.H. Ivanova V.S. Bonner W.M. DNA double-stranded breaks induce histone H2AX phosphorylation on serine 139. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5858. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rogakou E.P. Boon C. Redon C. Bonner W.M. Megabase chromatin domains involved in DNA double-strand breaks in vivo. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:905. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.5.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fernandez-Capetillo O. Lee A. Nussenzweig M. Nussenzweig A. H2AX: the histone guardian of the genome. DNA Repair. 2004;3:959. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xie A.Y. Hartlerode A. Stucki M. Odate S. Puget N. Kwok A. Nagaraju G. Yan C. Alt F.W. Chen J. Jackson S.P. Scully R. Distinct roles of chromatin-associated proteins MDC1 and 53BP1 in mammalian double-strand break repair. Mol Cell. 2007;28:1045. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stewart G.S. Wang B. Bignell C.R. Taylor A.M.R. Elledge S.J. MDC1 is a mediator of the mammalian DNA damage checkpoint. Nature. 2003;421:961. doi: 10.1038/nature01446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hanasoge S. Ljungman M. H2AX phosphorylation after UV irradiation is triggered by DNA repair intermediates and is mediated by the ATR kinase. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:2298. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muslimovic A. Nystrom S. Gao Y. Hammarsten O. Numerical analysis of etoposide induced DNA breaks. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5859. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zimmermann W.H. Melnychenko I. Eschenhagen T. Engineered heart tissue for regeneration of diseased hearts. Biomaterials. 2004;25:1639. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00521-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uemura M. Refaat M.M. Shinoyama M. Hayashi H. Hashimoto N. Takahashi J. Matrigel supports survival and neuronal differentiation of grafted embryonic stem cell-derived neural precursor cells. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88:542. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rohr S. Fluckiger-Labrada R. Kucera J.P. Photolithographically defined deposition of attachment factors as a versatile method for patterning the growth of different cell types in culture. Pflugers Arch. 2003;446:125. doi: 10.1007/s00424-002-1000-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Folch A. Jo B.H. Hurtado O. Beebe D.J. Toner M. Microfabricated elastomeric stencils for micropatterning cell cultures. J Biomed Mater Res. 2000;52:346. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(200011)52:2<346::aid-jbm14>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]