Abstract

Septins, a conserved family of GTPases, are heteropolymeric filament-forming proteins that associate with the cell membrane and cytoskeleton and serve essential functions in cell division and morphogenesis. Their roles in fungal cell wall chitin deposition, septation, cytokinesis, and sporulation have been well established and they have recently been implicated in tissue invasion and virulence in Candida albicans. Septins have never been investigated in the human pathogenic fungus, Aspergillus fumigatus, which is a leading cause of death in immunocompromised patients. Here we localize all the 5 septins (AspA-E) from Aspergillus fumigatus for the first time, and show that each of the 5 septins exhibit varied patterns of distribution. Interestingly AspE, which is unique to filamentous fungi, and AspD, belonging to the CDC10 class of septins, localized prominently to tubular structures which were dependent on actin and microtubule networks. Localization of AspD and AspE has never been reported in filamentous fungi. Taken together these results suggest that septins in A. fumigatus might have unique functions in morphogenesis and pathogenicity.

Keywords: Aspergillus fumigatus, septin, cell wall, septum, hyphal growth

1. Introduction

Hyphal growth is important for fungal pathogenesis, in part because hyphae facilitate invasive growth into the host tissue. The mechanical strength to withstand the pressure imposed by the host environment is provided by the fungal cell wall. Disruption of the cell wall has profound effects on hyphal morphology and, given the vital role the cell wall plays in fungal physiology, it is considered an excellent target for antifungal agents. Septins, a conserved family of GTPases, are heteropolymeric filament-forming proteins that associate with the cell membrane and cytoskeleton and serve essential functions in cell division and morphogenesis [1–3]. In the model yeast Sacchromyces cerevisiae, septins play roles in localized cell wall chitin deposition, septation, bud site selection, cell cycle control, cytokinesis, formation of mating projections, and sporulation [4–10]. Recently, they have been implicated in morphogenesis, tissue invasion and virulence of the pathogen Candida albicans [11–12]. While C. albicans septin mutants displayed aberrant cell wall chitin localization, they did not exhibit identical phenotypes indicating their distinct functions [11]. Moreover, septins involved in budding have been shown to mislocalize under cell wall stress [13]. Although the role of septins in cell division appears to be conserved, some exceptions to this include Schizosaccharomyces pombe and Caenorhabditis elegans, wherein septin mutation only delays cytokinesis or only alters specific cell division events, respectively [14–15].

While septins have been well characterized in mammalian cells and yeasts, not much is known on their distribution pattern and functions in filamentous fungi. More recently in the phytopathogenic basidiomycete, Ustilago maydis, 4 genes encoding the septins have been shown to be required for morphogenesis but not pathogenesis [16]. In the model Aspergillus nidulans five genes encoding the septins were identified [17] [aspA, B, C, D, E] and AspA, AspB and AspC have been localized and characterized [18, 19–20]. Similarly, the human pathogen A. fumigatus possesses 5 septins of which 4 septins (AspA-D) are orthologous to S. cerevisiae septins and the fifth septin (AspE) is unique to filamentous fungi (Suppl. Fig.1). While AspB is an essential protein and controls formation of septa, branch points, and asexual reproductive structures [18, 21], AspA and AspC have been shown to interact and regulate branching and development in A. nidulans. These data indicate septins function in limiting the formation of new growth foci in filamentous fungi [20].

We previously showed that A. fumigatus calcineurin A localizes to the septum and its deletion causes cell wall defects, irregular septation, and stunted hyphal growth [22–23]. As a preliminary step towards understanding the crucial roles septins could play in septum formation, cell wall structure, hyphal morphogenesis and development in this opportunistic pathogen, we analyzed their distribution during A. fumigatus growth.

2. Materials and methods

2. 1. Organism and culture conditions

A. fumigatus wild-type strain AF293 was used in all experiments. A. fumigatus cultures were grown on glucose minimal medium (GMM) at 37°C [23]. Escherichia coli DH5α competent cells (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) were used for subcloning. E. coli and A. fumigatus were transformed as described earlier [22].

2.2. Construction of septin genes expression plasmids

To localize all the five septins, the respective cDNAs encoding AspA, AspB, AspD and AspE were separately cloned at the N-terminus of egfp in the plasmid pUCGH at BamHI site to obtain the fusion constructs under the control of the otef promoter [24]. AspC cDNA was cloned at the C-terminus of mcherry in the plasmid pUCnCrH at NotI site. The respective plasmids were transformed separately into A. fumigatus strain Af293, as previously described [23], and the transformants were selected by resistance to hygromycin B. Strains expressing the respective septins were observed for their localization pattern at various stages of growth.

2.4. Protein extraction and Western analysis

The A. fumigatus strain expressing AspA-egfp fusion construct was grown in GMM liquid medium as shaking cultures for a period of 24 h at 37 °C. Cell extracts were prepared by homogenizing the mycelia using liquid nitrogen in buffer A (50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM KCl, 0.01% Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF and 1:100 protease inhibitor cocktail). Total cell lysate was initially centrifuged at 1200 rpm to eliminate the cell debris, and then the supernatant obtained was further centrifuged (5000 rpm, 10 min at 4 °C). The final supernatant fraction was collected and protein content was determined by Bradford's method. Approximately 50 μg protein was subjected to 12.5% SDS-PAGE and Western analysis using anti-GFP mouse monoclonal primary antibody and goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP labeled secondary antibody. Detection was performed using the SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate (Thermo Scientific, USA).

2.5. Nuclear staining

The AspB-GFP and AspE-GFP expression strains were grown in GMM liquid medium on coverslips for 18–20 h and stained with propidium iodide. Briefly the cultures were washed in 50 mM PIPES (pH6.7) for 5 min, fixed in 8% formaldehyde with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 40 min at 25ºC, washed in 50 mM PIPES (pH 6.7) for 10 min and treated with RNase (100 μg/ml) for 60 min at 37ºC. After washing with 50 mM PIPES (pH 6.7) for 10 min the fixed sample was stained with propidium iodide solution (12.5 μg/ml) in 50 mM PIPES (pH 6.7) for 5 min and observed under the fluorescence microscope.

2.6. Flourescence microscopy

Conidia of strains were inoculated in 100 μl of GMM medium on coverslips and after cultivation for a period of 18–20 h at 37º C were observed by fluorescence microscopy. To examine the effect of anti-microtubule agents, the respective strains were grown for 16–18 h at 37°C on coverslips, and then treated with the respective inhibitors for 1–2 h at 37°C and observed by microscopy.

2.7. Phylogenic analysis

Phylogenic analysis was performed on the Phylogeny.fr platform. Amino acid sequences were aligned with MUSCLE (v3.7) configured for highest accuracy and using the maximum likelihood method implemented in the PhyML program (v3.0 aLRT). Graphical representation of the phylogenetic tree was performed with TreeDyn (v198.3).

3. Results and discussion

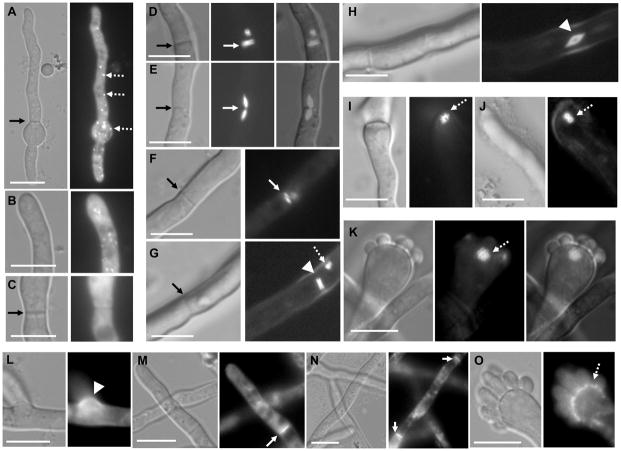

3.1. Septins AspA and AspB show dissimilar localization patterns

All the septins showed punctate or dot-like localization in swollen conidia (data not shown). AspA-GFP localized throughout the cytosol and in punctate dots or sometimes as cortical patches in both germlings and at hyphal tips (Fig.1A–C). Concentration of AspA-GFP was also seen in the hyphal tips, but surprisingly no septal localization was observed (Fig.1C). In A. nidulans hyphae, AspA-GFP also showed cytoplasmic localization that was often punctate at the cortex and brighter at hyphal tips as well as emerging branches apart from localizing at the septa [20]. To rule out the possibility of any cleavage in the AspA-GFP fusion protein which may result in cytosolic localization, Western analysis was performed using an anti-GFP antibody which showed a band corresponding to the molecular weight of AspA-GFP fusion protein (~68 kDa). No cleavage products from AspA-GFP fusion protein were detected (Suppl. Fig.2). Since most septins that localize to the cytosol are thought to function in membrane trafficking [19], AspA might be involved in directing growth through vesicle delivery at actively growing hyphal tips.

FIG. 1.

Localization of AspA, AspB and AspC in A. fumigatus. The respective septin expression strains were grown in GMM liquid medium on coverslips for 18–20 h and observed by fluorescence microscopy. (A) Localization of AspA-EGFP in germling, (B) hyphal tip and (C) sub-apical compartment. Black arrows indicate septa and arrow heads point to dot-like structures. (D–K) Localization of AspB-EGFP in hyphae and conidiophores. Arrows indicate septa, arrow heads point to rods and diamond-shaped structures. Ring-like structures are indicated by dotted arrows. (L–O) Localization of mcherry-AspC in hyphae and conidiophores. Arrows indicate septa and dotted arrow shows layered localization in the conidiophore. Scale bar, 10 μm.

In contrast to AspA, mcherry-AspC localized as a ring or cap at newly forming septa, emerging branches (Fig.1L) and also at mature septa (Fig.1M–N). Furthermore, AspC also localized as a layer at the junction between the vesicle and the phialides (Fig.1O), which was not observed with AspA. These results also indicate that, in contrast to A. nidulans [20], AspA and AspC in A. fumigatus do not exhibit similar pattern of localization. A. fumigatus AspA shows only 80% similarity to A. nidulans AspA, while the other septins exhibit over ~95% similarity between A. nidulans and A. fumigatus (data not shown). This difference in homology may account for the variation in localization pattern.

3.2. AspB showed distinct structures and localization patterns in various regions of the hyphae

AspB, an ortholog of S. cerevisiae CDC3, showed unique patterns of localization that varied between hyphae and the conidiophores (Fig.1D–K). At least 8 different patterns were observed, as summarized in Fig. 3B. Apart from localizing as rods on either sides of the septa (Fig.1D, F), diamond shaped structures fused with each other were seen across the septa and in the hyphal compartments (Fig.1E, H). The rod shaped structures were also present as a pair away from the septa (Fig.1G). The vesicles and conidiophores mostly contained dot-like and ring-like structures either as doublet or in aggregated forms (Fig.1I–K, Fig.3B). To assess if any of these structures associated with nuclei, we performed propidium iodide staining of the strain expressing AspB-GFP and observed that some dot-like structures were present close to the nuclei on either side, but generally the rod-like structures or the diamond-shaped structures did not localize or associate with the nuclei (Suppl. Fig.3). Although the functions of these structures have yet to be deciphered, it is possible that these may be novel cytoskeletal polymers that function as scaffolds for assembly of signaling complexes required for conidiophore development or sporulation. Interestingly, filamentous fungi do not contain sporulation-specific septins in contrast to yeasts (SPR3 and SPR28) [25]. A. nidulans AspB was also observed at the septa and as rings at the base of developing phialides, which later on disappeared as phialides matured [18].

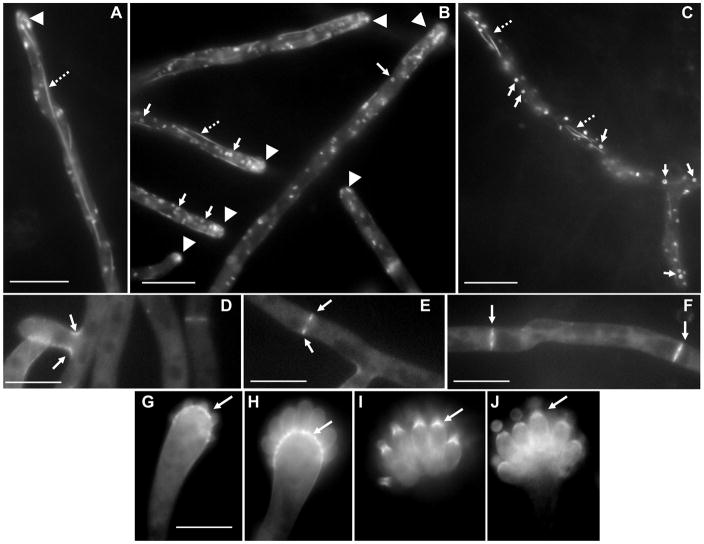

FIG. 3.

(A) Localization of AspE in A. fumigatus. The AspE-EGFP expression strain was grown in GMM liquid medium for 18–20 h and observed by fluorescence microscopy. Localization of AspE-EGFP in the hyphal tips and sub-apical compartments. Arrows point to septa and dotted-arrows indicate long filaments. Scale bar, 10 μm. (B) Summary of localization patterns of septins in hyphae and conidiophores.

3.3. AspD concentrates at the hyphal tip and localizes to ring-like structures and tubules, and septa

AspD-GFP localized to seemingly disconnected tubules and ring-like structures in the hyphae with a tip-high gradient (Fig.2A, B, C). In addition to localizing at branching sites (Fig.2D), both newly forming (Fig.2E) and mature septa showed prominent localization of AspD (Fig.2F). During conidiophore development, AspD clearly showed a thick layer of deposition in the vesicle at the points of emergence of the phialides (Fig.2G, H) and later in the upper portion of the phialides from where sporulation occurred (Fig.2I, J).

FIG. 2.

Localization of AspD in A. fumigatus. The AspD-EGFP expression strain was grown in GMM liquid medium for 18–20 h and observed by fluorescence microscopy. (A) Localization of AspD-EGFP in hyphal tip, (B–C) hyphal tips, (D–E) sub-apical compartments and branching sites. Arrow heads indicate hyphal tip-gradient, Arrows point to ring-like structures and dotted-arrows point to tubular structures. (F–I) Localization of AspD-EGFP during condiophore development. Arrows indicate layered localization in the conidiophores. Scale bar, 10 μm.

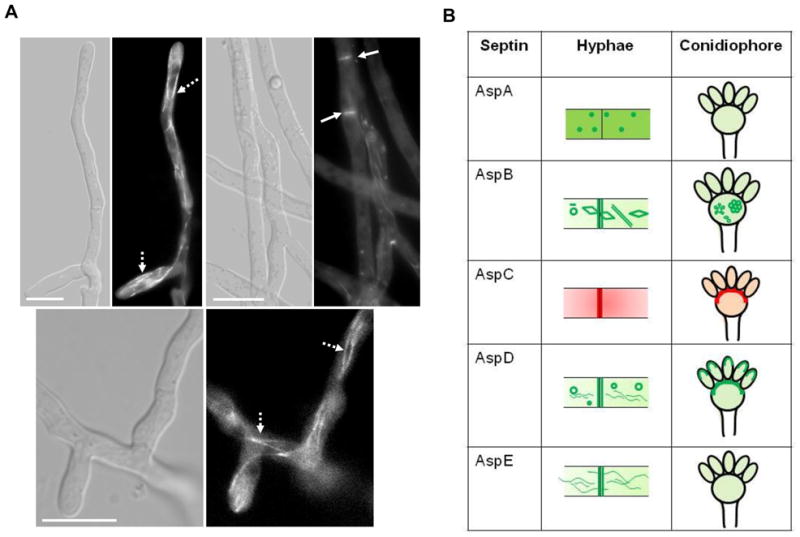

3.4. Filamentous fungal septin AspE localizes to long tubular structures and newly formed septa

In contrast to AspD, AspE localized to long filaments which appeared connected throughout the hyphae similar to microtubular networks (Fig. 3A, 3B). Moreover, ring-like structures were not evident and AspE was only observed at newly formed septa. Localization of AspD and AspE has never been reported in filamentous fungi and, interestingly, AspE belongs to a septin group which is unique to filamentous fungi [26]. Since both AspD and AspE localized prominently to tubular structures, it is possible that they may function in transport of other septins and proteins required for hyphal development. Differential localization patterns of all the septins observed in hyphae and conidiophores is summarized in Fig.3B.

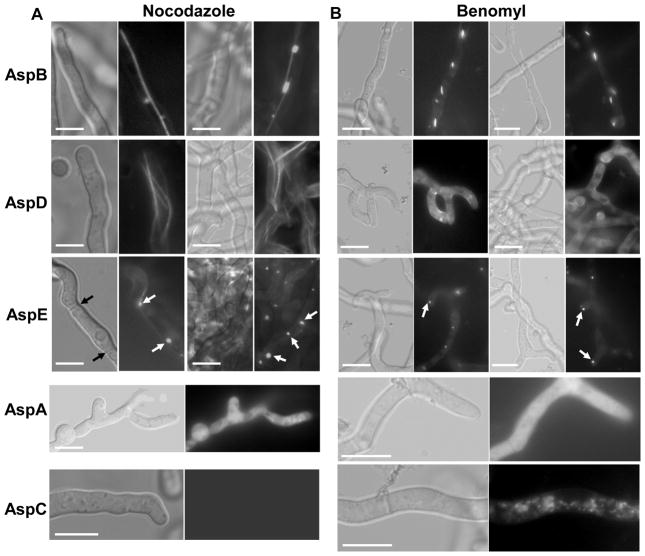

3.5. Actin and microtubule dependent localization of A. fumigatus septins

Since the interaction of septins with actin-based cytoskeleton is well established [8, 27] and recent studies show their association with microtubules [25, 28], we further examined the localization of septins using reagents that disrupt actin or microtubule networks. Treatment with cytochalasin A (80 μg/ml) completely mislocalized all the septins to the cytosol and none of the septins were found localized to the septum (data not shown). However, treatment with microtubule destabilizing agents (nocodazole or benomyl), at concentrations previously shown to completely destabilize microtubules [29], showed differential effects on septin structures (Fig.4). Whereas AspA completely dissociated into the cytosol in the presence of both the anti-microtubule agents (Fig. 4A, 4B; see panel AspA), AspC showed dot-like structures in the form of patches all over the hyphal compartments (Fig. 4A, 4B; see panel AspC). Treatment with nocodazole caused AspB and AspD to be retained on long filaments which, in the case of AspD, were more than 3 to 4 per hyphal compartment (Fig.4A; see panel AspB and AspD). Benomyl, which completely dissociates the microtubules, showed only shorter filaments or rods with AspB and completely mislocalized AspD to the cytosol (Fig. 4B; see panel AspB and AspD). Surprisingly, nocodazole or benomyl treatment caused AspE accumulation to dot-like structures which could be MTOCs (Microtubule Organizing Centers), as some of these were found near the septa and the others close to the hyphal tip region (Fig. 4; see panel AspE). MTOCs are nucleation centers for microtubules which were recently also identified to be present close to the hyphal tips and the septa [30]. Although the two anti-microtubule agents showed differential effects on localization of AspB and AspD, the septin filament structure containing AspE possibly depends on the integrity of microtubules because microtubule disruption by nocodazole or benomyl induced complete septin filament disruption. Propidium iodide staining of the strain expressing AspE-GFP treated with benomyl or nocodazole indicated that none of the dot-like MTOCs localized or associated with the nuclei (Suppl. Fig.4). It is possible that AspE could be a major septin involved in the organization of other septins or other cytoskeletal elements. The shifting of AspB and AspD to long filaments even after nocodazole treatment is intriguing because it has been shown that, regardless of their filamentous state, septins that co-localize with microtubules disassemble upon nocodazole treatment [31]. Further studies are required to understand exactly how these septin structures depend on the microtubules for their assembly or transport. In conclusion, these results strongly suggest that septin filaments interact not only with actin filaments but also with the microtubule network in filamentous fungi.

FIG. 4.

Effect of anti-microtubule agents on the localization of septins in A. fumigatus. The septin expression strains were grown in GMM liquid medium for 18 h and then nocodazole (80 μg/ml) [panel A] or benomyl (100 μg/ml) [panel B] were added. DMSO was included as control at appropriate concentrations. The cultures were grown for an additional 1–2 h and examined by fluorescence microscopy. Black arrows indicate septa and white arrows indicate dot-like AspE condensed structures (See AspE panel). Scale bar, 10 μm.

While our findings largely coincide with previously reported localization patterns for AspB and AspC and to some extent for AspA in A. nidulans, interestingly, the localization of AspE resembled the filamental pattern of Sep4 (CDC10 ortholog) in Ustilago maydis [16]. However, since the data presented here were derived from the ectopic expression of septin-GFP fusions under the control of the otef promoter, complete functionality and the distinct localization patterns have to be confirmed in strains deleted for each individual septin. Considering the interesting patterns of localization of AspD and AspE, we anticipate that deletion of these septins will reveal some interesting phenotypes in this filamentous fungus. Furthermore, the presence of 5 septins with varied localization patterns indicates that they are likely to be involved in various as-yet-unidentified cellular processes. For instance, a single septin, AspC, from A. nidulans could induce elongated pseudohyphae formation along with sporulating structures when expressed in S. cerevisiae, indicating the unique role filamentous fungal septins could play in morphological plasticity [32]. Future studies involving the inter-relationship of septins with microtubules and characterization of the septin-microtubule/septin-other protein interactions may unravel septin functions linking actin and microtubule networks and various other filamentous fungal-specific septin-dependent cellular functions.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gilden J, Krummel MF. Control of cortical rigidity by the cytoskeleton: emerging roles for septins. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2010;67:477–486. doi: 10.1002/cm.20461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.González-Novo A, Vázquez de Aldana CR, Jiménez J. Fungal septins: one ring to rule it all? Cent Eur J Biol. 2009;4:274–289. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McMurray MA, Thorner J. Septins: molecular partitioning and the generation of cellular asymmetry. Cell Div. 2009;4:18. doi: 10.1186/1747-1028-4-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeMarini DJ, Adams AE, Fares H, De Virgilio C, Valle G, Chuang JS, Pringle JR. A septin-based hierarchy of proteins required for localized deposition of chitin in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cell wall. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:75–93. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Douglas LM, Alvarez FJ, McCreary C, Konopka JB. Septin function in yeast model systems and pathogenic fungi. Eukaryot Cell. 2005;4:1503–1512. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.9.1503-1512.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gladfelter AS, Pringle JR, Lew DJ. The septin cortex at the yeast mother-bud neck. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2001;4:681–689. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(01)00269-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Longtine MS, Bi E. Regulation of septin organization and function in yeast. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:403–409. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00151-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roh DH, Bowers B, Schmidt M, Cabib E. The septation apparatus, an autonomous system in budding yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:2747–2759. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-03-0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidt M, Varma A, Drgon T, Bowers B, Cabib E. Septins, under Cla4p regulation, and the chitin ring are required for neck integrity in budding yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:2128–2141. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-08-0547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spiliotis ET, Nelson WJ. Here come the septins: novel polymers that coordinate intracellular functions and organization. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:4–10. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warenda AJ, Konopka JB. Septin function in Candida albicans morphogenesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:2732–2746. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-01-0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warenda AJ, Kauffman S, Sherrill TP, Becker JM, Konopka JB. Candida albicans septin mutants are defective for invasive growth and virulence. Infect Immun. 2003;71:4045–4051. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.7.4045-4051.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blankenship JR, Fanning S, Hamaker JJ, Mitchell AP. An extensive circuitry for cell wall regulation in Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(2):e1000752. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berlin A, Paoletti A, Chang F. Mid2p stabilizes septin rings during cytokinesis in fission yeast. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:1083–1092. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen TQ, Sawa H, Okano H, White JG. The C. elegans septin genes, unc-59 and unc-61, are required for normal postembryonic cytokineses and morphogenesis but have no essential function in embryogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:3825–3837. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.21.3825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alvarez-Tabarés I, Pérez-Martín J. Septins from the phytopathogenic fungus Ustilago maydis are required for proper morphogenesis but dispensable for virulence. PLoS One. 2010;5(9):e12933. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Momany M, Zhao J, Lindsey R, Westfall PJ. Characterization of the Aspergillus nidulans septin (asp) gene family. Genetics. 2001;157:969–977. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.3.969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Westfall PJ, Momany M. Aspergillus nidulans septin AspB plays pre- and postmitotic roles in septum, branch, and conidiophore development. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:110–118. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-06-0312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindsey R, Momany M. Septin localization across kingdoms: three themes with variations. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2006;9:559–565. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindsey R, Cowden S, Hernández-Rodríguez Y, Momany M. Septins AspA and AspC are important for normal development and limit the emergence of new growth foci in the multicellular fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Eukaryot Cell. 2010;9:155–163. doi: 10.1128/EC.00269-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Momany M, Hamer JE. The Aspergillus nidulans septin encoding gene, aspB, is essential for growth. Fungal Genet Biol. 1997;21:92–100. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.1997.0967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Juvvadi PR, Fortwendel JR, Pinchai N, Perfect BZ, Heitman J, Steinbach WJ. Calcineurin localizes to the hyphal septum in Aspergillus fumigatus: implications for septum formation and conidiophore development. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7:1606–1610. doi: 10.1128/EC.00200-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steinbach WJ, Cramer RA, Jr, Perfect BZ, Asfaw YG, Sauer TC, Najvar LK, Kirkpatrick WR, Patterson TF, Benjamin DK, Jr, Heitman J, Perfect JR. Calcineurin controls growth, morphology, and pathogenicity in Aspergillus fumigatus. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5:1091–1103. doi: 10.1128/EC.00139-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langfelder K, Philippe B, Jahn B, Latgé JP, Brakhage AA. Differential expression of the Aspergillus fumigatus pksP gene detected in vitro and in vivo with green fluorescent protein. Infect Immun. 2001;69:6411–6418. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.10.6411-6418.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pablo-Hernando ME, Arnaiz-Pita Y, Tachikawa H, del Rey F, Neiman AM, Vázquez de Aldana CR. Septins localize to microtubules during nutritional limitation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. BMC Cell Biol. 2010;9:55. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-9-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pan F, Malmberg RL, Momany M. Analysis of septins across kingdoms reveals orthology and new motifs. BMC Evol Biol. 2007;7:103. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finger FP. One ring to bind them. Septins and actin assembly. Dev Cell. 2002;3:761–763. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00371-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silverman-Gavrila RV, Silverman-Gavrila LB. Septins: new microtubule interacting partners. ScientificWorld Journal. 2008;8:611–620. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2008.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khalaj V, Brookman JL, Robson GD. A study of the protein secretory pathway of Aspergillus niger using a glucoamylase-GFP fusion protein. Fungal Genet Biol. 2001;32:55–65. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.2000.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zekert N, Veith D, Fischer R. Interaction of the Aspergillus nidulans microtubule-organizing center (MTOC) component ApsB with gamma-tubulin and evidence for a role of a subclass of peroxisomes in the formation of septal MTOCs. Eukaryot Cell. 2010;9:795–805. doi: 10.1128/EC.00058-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Westfall PJ, Momany M. Aspergillus nidulans septin AspB plays pre- and postmitotic roles in septum, branch, and conidiophore development. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:110–118. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-06-0312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lindsey R, Ha Y, Momany M. A septin from the filamentous fungus A. nidulans induces atypical pseudohyphae in the budding yeast S. cerevisiae. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9858. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.