Abstract

This article presents the findings of a survey completed by 1351 predominantly Mexican American middle school students residing in a large urban center in the U.S. Southwest. The study explores possible associations between drug use attitudes and behaviors and gender (biological sex), gender identity, ethnicity, and acculturation status. Based on the concepts of “machismo” and “marianismo” that have been used to describe Mexican populations, four dimensions of gender identity were measured: aggressive masculinity, assertive masculinity, affective femininity, and submissive femininity. In explaining a variety of indicators of drug use behaviors and anti-drug norms, gender alone had limited explanatory power, while gender identity—often regardless of gender—was a better predictor. Aggressive masculinity was generally associated with higher risk of drug use, while the other three gender identity measures had selected protective effects. However, the impact of gender identity was strongly mediated by acculturation. Less acculturated Mexican American students reported lower aggressive masculinity scores than non-Latinos. Less acculturated Mexican American girls reported both the lowest aggressive masculinity scores and the highest submissive femininity scores. More acculturated Mexican American students, along with the less acculturated Mexican American boys, did not appear to be following a polarized approach to gender identity (machismo and marianismo) as was expected. The findings suggest that some aspects of culturally prescribed gender roles can have a protective effect against drug use behaviors and attitudes, possibly for both girls and boys.

Introduction

Cultures ascribe certain behaviors to each gender, which are reinforced through socialization during childhood. In Western cultures, gender roles have undergone significant changes since movements for women's liberation became increasingly influential in the late 20th century. However, gender-based expectations around use of alcohol and drugs persist. Drinking and drunkenness remain more socially acceptable for males than females, expectations that are strongly reinforced through peer relationships (Huselid & Cooper, 1992).

Research on gender roles and drug use has investigated the relationship between sex-linked personality characteristics and substance use patterns. Aggression-related variables have been associated with male alcohol use as well as heavy and problematic use, while emotional warmth and concern for others has been inversely associated with alcohol use for females (Huselid & Cooper, 1992). Research on gender roles and alcohol use has found that gender roles consistently explain differences in use patterns (Huselid & Cooper, 1992). Other research has found that certain sex-linked personality variables, such as aggression, are significantly associated with use of alcohol and other drugs by males and females respectively (Thomas, 1996). Recent studies have also shown that interpersonal dominance typically associated with masculinity predicts more substance use for adolescents of both genders, while nurturing qualities associated with femininity are related to drug refusals (Kulis, Marsiglia, & Hecht, 2002).

Feminist and gender socialization perspectives, on the other hand, have focused on conflict between cultural expectations and the devalued feminine role as placing adolescent females at risk for health and mental health problems. Females' use of drugs, it is argued, may be related to self-image, weight loss, and depression, which are different causative factors than those identified for teen boys (Slater, Guthrie, & Boyd, 2001). According to theories of female development, girls and women are more concerned about relationship issues at all developmental stages (Surrey, 1991). This relational focus may affect adolescent drug use patterns, as female adolescents may be influenced by male partners to engage in high-risk behaviors (Moon, Hecht, Jackson, & Spellers, 1999). These parallel efforts to study the etiology of drug use by male and female adolescents often perpetuate a dichotomous approach to gender differences that may not reflect the experience of today's ethnically diverse youth. For example, feminist theorists have questioned some assimilation/acculturation frameworks due to their lack of understanding of gender differences within ethnic/racial groups (e.g., Hurtado, 1996).

Gender and Drug Use among Ethnically Diverse Adolescents

Age has been identified as a key intervening variable in gender role formation. Since gender role orientation continues to develop during adolescence, differences between younger and older adolescents in the level of identification with gender roles and levels of empathy have been studied. Female and male adolescents become more indistinguishable from each other as they grow into young adults, in part due to a decreased adoption of stereotypical gender roles (Karniol, Gabay, Ochion, & Harari, 1998; McCreary, Newcomb, & Sadava, 1998).

Drug use among adolescents in the U.S. increased substantially in the 1990s before dipping slightly at the end of the decade. Current epidemiological studies indicate that use of drugs increases with age, that males generally use drugs more frequently than females, and that there is some ethnic variation in usage patterns (Kann et al., 2000; Marsiglia, Kulis, & Hecht, 2001). Increased use of cigarettes and alcohol among younger adolescents often leads to greater use of marijuana, leading, in turn, to subsequent use of other drugs such as cocaine, heroin, hallucinogens. Early drinking and smoking seem to be significant predictors of later drug use among adolescents (Merrill, Kleber, Shwartz, Liu, & Lewis, 1999).

National data on adolescent drug use indicates that 81% of high school students had at least one drink of alcohol in their lifetime, and that 10th to 12th graders, males and Latinos were more likely to use alcohol than younger students, females, and African American or White students (Kann et al., 2000). Half of all students had one or more drinks within the previous month, with patterns similar to those described above in relationship to age, gender, and ethnicity. Male students were significantly more likely to report episodic heavy drinking than females, and White and Latino students were significantly more likely than African American students to report such behavior (Kann et al., 2000).

Despite varying drug use rates among adolescents, it appears that the prevalence of casual drug use is roughly equivalent for boys and girls (Sarigiani, Ryan, & Petersen, 1999). Reviews of the literature on adolescent alcohol use find little or no gender difference in casual use, but significant differences in heavy use of alcohol, with older studies showing the greatest gender differences (Randolph, Stroup-Benam, Black, & Markides, 1998). Males are more frequent users of alcohol on a daily basis and in high-volume during their high-school years (Donovan, 1996). Overall, male adolescents have traditionally been identified as heavier and more frequent users than females (Kandel & Wu, 1995).

Gender norms are also known to affect alcohol use. Conventionally, men have been identified as exhibiting traits like assertiveness, instrumentality, and aggressiveness, and women as manifesting expressive traits. The individuals whose personal gender role orientations conform to conventional gender stereotypes can be either placed at higher risk or protected from heavy and problematic alcohol use, as it is socially acceptable for males to drink and females to abstain (Huselid & Cooper, 1992). Traditional gender attitudes thus relate positively to alcohol use among males and are negatively related to alcohol use for females. Further, those individuals who adopt the gender role orientation stereotypically assigned to the opposite sex would be expected to drink more if they have adopted masculine attributes, and vice versa if they have adopted feminine attributes (Kulis et al., 2002).

Gender differences have been particularly salient in substance use progression, with tobacco playing a larger role in drug use for females than for males (Kandel, Yamaguchi, & Chen, 1992; Yu & Williford, 1992). Recent trends show rising rates of cigarette and marijuana use by teen females, as well as earlier use of alcohol and cigarettes than exhibited by males, and an increase in rates of females driving under the influence of alcohol (Slater, Guthrie, & Boyd, 2001; Light, 2000). Gender differences in marijuana use, the most commonly used illicit substance among adolescents, appear to be changing. Specifically, for the casual user, gender differences are narrowing (Sarigiani et al., 1999), although males continue to have much higher rates of heavy marijuana use than females do (Schinke, Tepavac, & Cole, 2000). Developmental differences between boys and girls have been used as the main explanation for these trends. Peer drug use has been shown to influence adolescents' drug use among boys in combination with other factors such as residing in rural communities, having lower self esteem, low socioeconomic status, and having alcoholism in their families (Howard, Walker, Walker, Cottler, & Compton, 1999).

Little is known about the transferability or applicability of these important gender differences in drug use to ethnically diverse populations. For example, peer influence appears to have a stronger impact on substance use initiation among White and Latino than among African American youth (Resnicow, Soler, Braithwaite, Ahluwalia, & Butler, 2000). Because much of the existing research focuses on mainstream/majority culture, a better understanding of gender-specific research by region and their dominant ethnic groups is needed. This study focuses on the experiences of Mexican American adolescents as members of a community with a historic and growing presence in the Southwest region of the U.S.

Gender and Drug Use among Mexican American Youth

Differences in drug use between male and female Mexican American youth have not yet been well documented. Mexican Americans of all ages report a lower frequency but higher volume of alcohol use than non-Hispanic Whites (Randolph et al., 1998). A similar use pattern exists among middle school students. Mexican American eighth graders self-report higher use of marijuana, cocaine, crack, heroin, and steroids than non-Hispanic White youth (Chavez & Swaim 1992). Studies comparing Mexican American and non-Hispanic White students have found differences in drug use based on gender but not on ethnicity (Arrellano, Chavez, & Deffenbacher, 1998). Research conducted solely with Mexican Americans has produced more discernable intragroup differences, and suggested reasons for them. Cultural values within this ethnic group support different alcohol use norms by gender, such that men are allowed to drink when and where they feel it is necessary while women are traditionally only allowed to drink within the safe confines of masculine boundaries, e.g., in a mixed sex environment where their actions can be watched over (Wycoff, 2000). On the other hand, few gender differences appear among heavy alcohol users in Latino samples (Felix-Ortiz & Newcomb, 1999).

Differences among casual users may be attributed to Mexican American women's stronger collectivist approach to abstinence that takes into account risks to family and friends over individual needs and desires (Perea & Slater, 1999). Acculturation appears to weaken collectivism and seems to have a direct effect on increasing the use rate of alcohol for Mexican American women but not for Mexican American men (Alaniz, Treno, & Saltz, 1999; Marsiglia & Waller, 2002; Randolph, et al., 1998). Although Mexican American women who have not been highly acculturated have very high abstention rates, as they become more acculturated they show a convergence in drinking status approximating the proportion of male drinkers (Alaniz et al., 1999). Acculturation and acculturative stress have also been identified as influencing alcohol use among middle school students primarily through the deterioration of traditional Latino family values and familial behaviors (Gil, Wagner, & Vega, 2000).

Machismo and Marianismo

Acculturation appears to be related to the gender roles, gender identities, and the drug use behaviors of Mexican American males and females (Kulis et al., 2002; Orozco & Lukas, 2000). However, “machismo” and “marianismo,” central gender role influences for Mexican men and women, are often absent in the conceptualization of studies that explore the impact of gender and acculturation on substance use. Machismo, from a Mexican cultural and psychological perspective, relies on theoretical conceptualizations suggesting that it originated in response to the Spanish Conquest of the Americas. From this perspective it is a male gender role emphasizing emotional invulnerability, patriarchal dominance, and aggressive or controlling responses to stimuli, but masking more deeply rooted feelings of inferiority and ambivalence toward women (Goldwert, 1983).

There is considerable debate regarding this view of Mexican machismo: whether it is in fact a social myth imposed by researchers (Mirandé, 1979); whether it is due to socioeconomic vulnerability rather than culture (Baca Zinn, 1982a); and whether it obscures another more positive set of masculine traits that are also parts of machismo (Mirandé, 1985). This second meaning of machismo is centered on traits such as honor, respect, bravery, dignity, and family responsibility (Marsiglia et al., 2001; Neff, 2001). Although these two conceptualizations of machismo appear to coexist in the minds and behaviors of many Mexican American adolescents of the Southwest (Kulis et al., 2002; Marsiglia & Holleran, 1999), the two dimensions have been shown to be distinguishable empirically with separate sets of indicators (Neff, 2001).

In a manner that is often portrayed as complementary to machismo (Gil & Vazquez, 1996), female gender roles in Mexican culture are governed by norms that are captured in the notion of marianismo. According to a prevailing view, marianismo reflects cultural dynamics that consider women to be spiritually superior to men because of their greater capacity for humility and sacrifices for family, as well as their sense of sadness and forbearance for the imperfections of men (Stevens, 1973). Some view the subordination of women through marianismo as a product not of culture, but of the structural forces that confine women's roles to domestic rather than public spheres of action (Baca Zinn, 1982a, 1982b). Regardless of their source, like machismo, the expectations encoded in marianismo can be segregated conceptually and empirically into two dimensions, one focusing on a sense of collectivism, self-sacrifice, devotion to family, and nurturance, and another encouraging dependency, submissiveness, passivity, and resignation in the face of oppression.

For the purposes of this study, the differing conceptions of machismo and marianismo will be explored as distinct dimensions that fit within more widely used approaches to understanding gender identity. Similar distinctions have emerged in efforts to develop multidimensional measures of gender identity based on sex-typed personality traits and orientations, traditional gender role attitudes, and gender role stress (Antill, Cunningham, Russell, & Thompson, 1981; Marsh & Myers, 1986; McCreary et al., 1998; Ricciardelli & Williams, 1995; Russell & Antill, 1984), including those developed specifically for Mexican populations (Lara-Cantu, Medina-Mora, & Gutiérrez, 1990). The negative (hypermasculinity) and more positive (traditional honor) dimensions of machismo parallel those that have distinguished between a negative, undesirable, or “aggressive” masculinity and a positive, desirable, or “assertive” masculinity. The two notions of marianismo also parallel more general conceptions of feminine gender identity: a positive, expressive, or “affective” femininity, and an undesirable, “submissive” femininity. Helgeson (1994) argued that common constructs underlie the many different scales that have been advanced to measure masculinity and femininity, primarily a distinction between a sense of “agency” (focus on the self and its separation from others) and a sense of “communion” (focusing on others and connections to them).

In exploring intragroup differences in the substance use behaviors and norms of a sample in which Mexican American youth predominate, this study pursues several objectives. We first examine gender differences in these outcomes and the degree to which they are superseded or moderated by different dimensions of gender identity. Second, we explore ethnic differences in the impact of gender identity on substance use by contrasting the Mexican American majority with their non-Latino middle school classmates. Finally, using language use as a proxy for acculturation, we examine a general hypothesis that gender differences in drug use and drug norms will be greater among the less acculturated Mexican American youth, and that these differences are largely explained by differences in gender identity.

Methodology

Respondents

This study analyzes responses from 1351 eighth-grade students who completed questionnaires in their school classrooms in Spring 2000. They were enrolled in five middle schools that participated in a 2-year long drug prevention study in a large city in the Southwest. These schools are ethnically diverse, with non-Hispanic White students in the numerical minority, and nearly three quarters claiming some Mexican heritage. The schools serve primarily lower income neighborhoods of the central city. Within these schools, every eighth grader was selected as a participant in the study.

The respondents are a subgroup of a larger sample of 3563 eighth graders who completed the last of four waves of data collection for the drug prevention study. The larger study included 35 schools spread over nine school districts. Only the respondents from five of these schools completed a supplemental form of the standard questionnaire that probed aspects of the student's gender identity. Comparisons of the respondents from the five selected schools with those from the remaining 30 schools in the larger study indicate that the two groups are statistically indistinguishable in terms of gender, academic grades, and every drug-related outcome examined in this article. However, Latino students did predominate somewhat more in the five selected schools. Collectively, these five schools have higher proportions of Latino enrollment (76%) than the unselected schools (64%). Among the selected schools, Latino students were in the majority in four and in the plurality in the remaining school. In the unselected schools, Latino students were a majority in 23, a plurality in 2, and in the minority in 5 of the schools.

Surveys

University-trained survey proctors administered a 45-minute written questionnaire, available back-to-back in either English or Spanish. The surveys were administered during regular school hours in an eighth-grade science, health, or homeroom class, depending on the scheduling and administrative needs of individual schools. Prior to the survey administration, school administrators sent letters to the parent(s) of every student explaining the nature of the study and requesting their consent to have their child participate in the study and complete the study surveys. These procedures were reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Boards at the investigators' university and at each school district. During the survey administration, students were first informed that this was a voluntary university research project rather than a normal school activity and were guaranteed the confidentiality of all their responses. All students present the day of survey administration agreed to complete the questionnaire, and absent students were not contacted further. To ensure their anonymity no student names or ID numbers were recorded on the questionnaires, no teachers were present during the survey administration, and members of the study team collected all questionnaires and returned them for coding to the study office. Teachers and school administrators had no access to the original data, but were later presented with reports on aggregated student responses.

Demographic Profile of Participants

Excluding those who failed to report key demographic information (gender, race/ethnicity, age), there were 1332 respondents. The students ranged from 11 to 18 years of age, but 92% were either 13 or 14 years old. There were nearly equal numbers of males (52%) and females (48%). Most of the students were from lower income families and received either a free (86%) or reduced price school lunch (4%). A substantial majority (67%) indicated that Spanish was spoken at home at least as often or more often than English, and almost half (49%) said they spoke Spanish with friends at least as often as they spoke English. Thirteen percent of the respondents chose to complete the questionnaire in Spanish rather than English.

The ethnic and racial identities of the respondents were varied and sometimes multi-ethnic, but Mexican heritage dominated. The largest group, nearly two thirds overall (66%) identified solely as Mexican or Mexican American or Chicano. Another 10% claimed Mexican heritage along with that of another racial or ethnic group (most commonly White, followed by other Latino, and then by American Indian.) The next most numerous group identified solely as non-Hispanic White (8%), followed by non-Mexican Latinos (5%), African Americans (4%), American Indians (3%), those claiming multiple ethnicities other than Mexican (3%) and Asians (1%). In reporting results, the small number of non-Mexican Latinos has been included with Mexican Americans, the group with which they have closer cultural affinities than the comparison group of non-Latinos. The Latino group is described in results as “Mexican American” to emphasize its cultural specificity and the predominance of Mexican origins within the group.

Variables

A series of Likert-type items were developed to capture students' behaviors and attitudes concerning use of alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana. Students also completed a core demographic section in which they were asked to identify with one or more ethnic groups.

Lifetime and Current Drug Use

A set of dependent variables was constructed from questions about the amounts and frequency of drug use, modeled after questionnaire items used by Flannery, Vazsonyi, Torquati, and Fridrich (1994). These measures were chosen due to their developmental specificity for the age group being studied. In addition, these measures are similar to scales used in other large studies of early adolescent drug use (e.g., Kandel, 1995; Newcomb & Bentler, 1986). We employ measures of the amounts of lifetime use for three substances. Students indicated how many drinks of alcohol, how many cigarettes, and how many times they had used marijuana in their entire life. Later, they indicated separately the amounts of these substances they had consumed in the past 30 days. Recent use of alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana was also assessed in terms of frequency of use in the last 30 days. The original Likert scale responses (e.g., 1 = “None” to 10 = “Over 100 drinks;” 1 = “None” to 10 = “More than 20 packs;” and 1 = “Never” to 10 = “Over 30 times”) produced distributions that were highly skewed toward low rates of drug use. To obtain better fitting models, we transformed the categories of the original responses by calculating their natural log. We report results for lifetime use by specific substance, but for recent use we have combined all the items into a single scale (mean).

Age of Initial Drug Use

Information from three questions was combined to identify the earliest age, in years, that students began using alcohol, cigarettes, or marijuana. Our analyses of this outcome are restricted to students who indicated they had used at least one of these three substances.

Anti-Drug Norms

Using 26 of the original questionnaire items, we created eight additive scales that were designed to measure different aspects of the student's attitudes toward drug use: personal approval/disapproval; personal intentions to use drugs; expectation of injunctions by significant others in response to the respondent's drug use; the perceived extent of drug use by peers and acquaintances; perceived positive consequences to drug use; and confidence in ability to refuse drug offers. Two of these scales measured anti-drug personal norms: the students' opinion on whether use of alcohol, cigarettes and marijuana is “OK” for someone their age; and whether it is “OK” for anyone to use “hard drugs” (LSD, crack, cocaine) or inhalants. The five component items for these two scales were scored from “definitely OK” (1) to “definitely not OK” (4). Anti-drug personal intentions were captured with three items indicating the likelihood that the student would refuse future drug offers (of alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana), each scored from “definitely yes” (1) to “definitely no”(4). Anti-drug injunctive norms were measured in two separate scales focusing on two important reference groups for these students, their parents, and friends. The respondents reported how angry their parents would be (from “not at all” [1] to “very angry” [4]), and how their best friends would react (from “very friendly” [1] to “very unfriendly” [4]), if they discovered the respondent was using each of three substances (alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana). Descriptive drug use norms were also measured with a scale composed of three items: the proportion of school peers who have tried any drugs, as well as the proportion who use drugs regularly [from “hardly any” (1), “some” (2), “half” (3), to “most” (4)]; and the number of their friends who use alcohol, cigarettes, or marijuana at least once a month, scored from 0 to 4 or more. Another drug norm scale, based on six items, indicated the degree to which the respondent thinks that alcohol or marijuana use can have positive consequences for users, such as improving group acceptance, enlivening parties, having more fun, decreasing nervousness, sharpening concentration, and making food taste better, each scored from “never” (1), “almost never” (2), “sometimes” (3), “often” (4), to “most of the time” (5). The final drug norm scale captured the respondents' confidence in their ability to resist an offer of alcohol, cigarettes, or marijuana from a family member, from friends, and from a stranger, with three component items scored from “not at all sure” (1) to “very sure” (5).

Although the eight scales had good to excellent internal consistency as indicated by Cronbach's alpha coefficients (.75 to .86), as separate outcomes they were only weakly related to our gender identity measures. In an attempt to improve the validity of measurement as well as model fit, we performed a principal components factor analysis of the eight scales and found they cohered strongly (loadings ranging from .54 to .83) around a single factor. We used the resulting factor score as a measure of the degree to which the respondent adhered to anti-drug norms.

Gender and Gender Identity

Respondents' gender label was measured from an item asking students to check whether they were female or male. Gender identity measures were constructed from 12 questions that asked students to describe their gender-typed traits and behaviors using five Likert response categories [“How often do you feel about yourself in the following ways: never (0), rarely (1), sometimes (2), often (3), always (4)”]. These items were based on those reported by Antill and others to map both positive and negative aspects of masculinity and femininity (Antill et al., 1981; Marsh and Myers, 1986; Ricciardelli and Williams, 1995; Russell and Antill, 1984), and the items are closely related to those developed to measure gender identity in a Mexican sample using items adapted from the Bem (1974) Sex Role Inventory (Lara-Cantu et al., 1990). The three more positive or desirable masculinity items capture a sense of confidence and assertiveness: “I am skillful at getting things done and taking charge,” “I am sure of my talents and abilities,” and “I tell people what I think, even if they disagree with me.” A negative realm of masculinity, concerned with dominance and control over others, was measured with: “I order around the kids in my class or neighborhood,” “I feel superior to my classmates and peers,” and “I like to show-off in front of others.” The scale consisting of items that describe nurturing and expressive aspects of femininity included the following items: “I am a kind, warm, and gentle person,” “I am emotional and show my feelings to others,” and “I can tell when someone is feeling sad or depressed.” In contrast, more negative aspects of femininity tapping a sense of dependence and inadequacy were captured through: “I feel timid and shy around others,” “I am too critical of myself or ‘get down’ on myself,” and “I feel weak and helpless.” These items were combined to produce four indexes, in each case by calculating mean values of the three component items. We use labels suggested by others for the four gender identity scales: “assertive masculinity,” “aggressive masculinity,” “affective femininity,” and “submissive femininity” (Lara-Cantu et al., 1990).

Ethnicity and Acculturation

Because of the overwhelming predominance of Mexican American respondents and the small numbers from other ethnic groups, in multivariate analyses we include the other Latinos with the Mexican Americans and contrast this group with all other non-Latino respondents combined. The Mexican American and other Latino respondents are further broken down by a proxy measure for their degree of acculturation into majority culture, as indicated by whether or not they used Spanish as their predominant language. This was determined in two ways: students who chose to complete the questionnaire in Spanish, and/or those who indicated that they spoke Spanish with their friends “all” or “most” of the time were considered to be Spanish dominant and less acculturated. All the remaining respondents who indicated they were Mexican, Mexican-American, Chicano/a, or another Latino group were assigned to a second group of more acculturated Latinos. A third group of non-Latinos consists of all the remaining respondents, most of whom indicated they were “White.” The non-Latino group is employed as the reference group in multivariate analyses that control for ethnicity/acculturation.

Control Variables

Several control variables were entered into the multivariate analyses. The student's age is measured in years. Socioeconomic status is roughly distinguished with a dummy variable contrasting those who do and do not receive a free or reduced price school lunch. The student's “usual grades in school,” on a Likert scale from 0 (mostly F's) to 9 (mostly A's), are a self-reported global assessment of academic performance.

Analysis Strategy

The results presented below examine the role of gender identity in drug use, whether the impact of gender identity is independent of the role of gender labels or perhaps supersedes it, whether gender labels and gender identity operate interactively, and whether gender and gender identity relate to drug use in different ways for more and less acculturation Latinos and non-Latino middle school students. The key findings are ordinary least squares regression results that predict the degree to which students have used drugs in their lifetime and in the recent past, their age of initiation into drug use, and the strength of their anti-drug norms. As predictors we enter gender labels and the four measures of gender identity, along with controls for ethnicity/acculturation, age, SES, and academic performance. To examine whether the gender identity measures operate differently by ethnicity and acculturation, we also present separate results for less acculturated (Spanish dominant) Mexican Americans/Latinos, more acculturated Mexican Americans/Latinos, and non-Latinos. All the regression estimates were free of multicollinearity as indicated by low variance inflation factors, all under 1.6, and nearly all below 1.2.

Findings

Descriptive statistics and selected correlations for all dependent and independent variables are presented in Table 1. The means suggest that the typical student has used alcohol in his or her lifetime more than any other substance, followed with decreasing frequency by cigarettes, and then marijuana. Among those who had used any of these drugs, the self-reported age of initiation into drug use was around age 10. Students more often describe themselves as frequently meeting the criteria for positive versions of masculine and feminine gender identity (assertive masculinity and affective femininity) than their negative counterparts (aggressive masculinity and submissive femininity).

Table 1. Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations for Variables in the Analysis.

| Correlations with: | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | M | SD | Assertive Masculinity | Aggressive Masculinity | Affective Femininity | Submissive Femininity | |

| Lifetime alcohol use | 1342 | 1.064 | 0.8 | −0.073** | 0.138*** | −0.137*** | −0.054* |

| Lifetime cigarettes use | 1345 | 0.668 | 0.766 | −0.059* | 0.143*** | −0.117*** | 0.015 |

| Lifetime marijuana use | 1344 | 0.464 | 0.698 | −0.020 | 0.209*** | −0.084** | −0.063* |

| Past 30-day drug use | 1339 | 0.388 | 0.604 | −0.022** | 0.166*** | −0.078** | −0.045 |

| Age of initiation in drug use | 834 | 10.221 | 2.331 | 0.017 | −0.165*** | 0.067 | 0.074* |

| Anti-drug norms | 1297 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.144*** | −0.294*** | 0.207*** | 0.01 |

| Gender (M = 1; F = 0)a | 1342 | 0.519 | 0.499 | −0.076†† | 0.145††† | −0.265††† | −0.106††† |

| Assertive masculinity | 1347 | 3.631 | 0.815 | 1.000*** | −0.182*** | 0.434*** | −0.189*** |

| Aggressive masculinity | 1343 | 2.191 | 0.79 | 0.182*** | 1.000*** | 0.039 | 0.104*** |

| Affective femininity | 1348 | 3.423 | 0.794 | 0.434*** | 0.039 | 1.000*** | 0.133*** |

| Submissive femininity | 1347 | 2.271 | 0.787 | −0.189*** | 0.104*** | 0.133*** | 1.000*** |

| Age | 1351 | 14.462 | 0.557 | −0.043 | 0.046 | −0.042 | 0.036 |

| Free or reduced school luncha | 1351 | 0.897 | 0.302 | 0.021 | −0.122††† | 0.037 | 0.043 |

| Usual grades | 1331 | 6.416 | 1.753 | 0.275*** | −0.015 | 0.160*** | −0.062* |

| Less Acculturated Mexican American (Y = 1; N = 0)a | 1343 | 0.157 | 0.364 | −0.027 | −0.149††† | 0.017 | 0.037 |

| More Acculturated Mexican American (Y = 1; N = 0)a | 1343 | 0.672 | 0.469 | −0.009 | 0.037 | 0.009 | 0.027 |

| Non-Latino (Y = 1; N = 0)a | 1343 | 0.171 | 0.376 | 0.037 | 0.099††† | −0.028 | −0.069† |

Correlations between each of the gender identity index scores and several dummy variables are presented to indicate the direction of the relationship. Based upon a separate set of unreported ANOVA tests, statistically significant differences in mean gender identity scores between the two categories of the given dichotomy were found at p < .05 (†), or p < .001 (†††).

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Boys report higher scores than girls on the aggressive masculinity index, as suggested by the bivariate correlations listed in Table 1 and verified in ANOVA tests that are not presented here. Boys also have lower average scores than girls on the other three gender identity indexes, including the assertive masculinity index. One aspect of gender identity—aggressive masculinity—is consistently associated with less desirable drug outcomes: more drug use, earlier initiation, and weaker anti-drug norms. All of the other three measures of gender identity are associated with at least some desirable drug outcomes. Affective femininity is clearly, although modestly, associated with less lifetime and recent drug use as well as stronger anti-drug norms. Assertive masculinity and submissive femininity are associated with a few desirable outcomes, but only quite weakly.

The gender identity indexes are not strongly related to the control variables in this study. The strongest relationships are small positive correlations between academic performance (grades) and the positive versions of gender identity—assertive masculinity and affective femininity. Lower income students, interestingly, report slightly lower aggressive masculinity scores. Differences in gender identity by ethnicity and acculturation status are also suggested by the correlations. Less acculturated (Spanish dominant) Mexican American respondents report relatively low aggressive masculinity scores while for non-Latinos these scores are relatively high. Non-Latinos also have somewhat lower submissive femininity scores than the other respondents. But these comparisons obscure more important differences in gender identity that emerge once gender and ethnicity/acculturation are examined jointly.

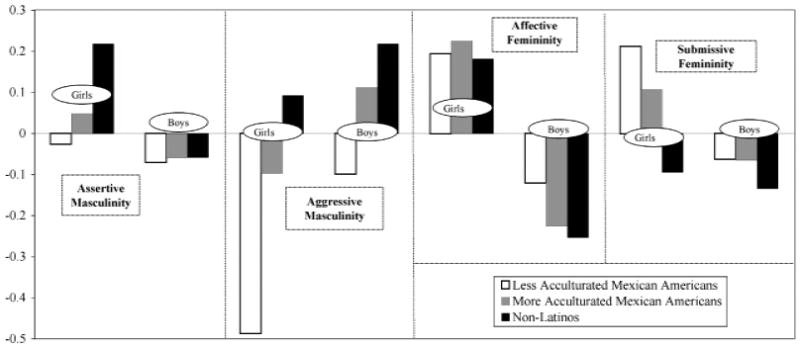

In Figure 1 we report the mean gender identity scores (after these scores were first centered on the overall means of the sample as a whole) separately for boys and girls in each ethnicity/acculturation category. Although girls overall have higher scores on the assertive masculinity index, this is mostly due to non-Latino girls, who report significantly higher scores than non-Latino males as well as higher scores than both the more and less acculturated Mexican American girls. The largest group differences in means appear for aggressive masculinity, with additive effects by gender and ethnicity/acculturation. Within each gender group, less acculturated Mexican American respondents report the lowest aggressive masculinity scores, and non-Latinos the highest, with more acculturated Mexican Americans in between. Within each ethnic/acculturation group boys have higher aggressive masculinity scores than girls do, although the gender difference among the non-Latinos falls just outside the conventional threshold of statistical significance (p = .06). For the affective femininity index boys report significantly lower scores than girls in each ethnic/acculturation group, but there are no significant differences among the ethnic/acculturation groups. Mean scores for the submissive femininity index are arrayed in an inverted pattern to the one found for aggressive masculinity, but with smaller differences. Both groups of Mexican American boys—the less and the more acculturated—report significantly lower submissive femininity scores than their female counterparts, although there is not a significant gender difference among non-Latinos. Conversely, there is a significant ethnic/acculturation difference in submissive femininity among girls, but not boys, with non-Latino girls reporting lower scores than the two groups of Mexican American girls. Overall, the results suggest that gender identity is more strongly polarized among the less acculturated Mexican American students, and that substantial numbers of non-Latino boys and girls fail to conform to gender role stereotypes, in some cases (assertive masculinity) even reversing them.

Figure 1.

Gender identity means, by gender and ethnicity acculturation.

To explore how these intertwined factors of gender, gender identity, and ethnicity/acculturation relate to drug use, hierarchical ordinary least squares regression models are presented in Table 2. They first enter gender label alone, preceded by the control variables, as predictors of lifetime use of the three most commonly used substances (Model I). Next, the gender identity indexes are added as predictors (Model II), and then the results are separated by ethnicity/acculturation (Model III). The sequence of regressions indicates that although boys report significantly more lifetime use of alcohol and marijuana than girls do, these gender differences do not persist when gender identity measures are added as predictors. Although assertive masculinity is unrelated to lifetime drug use in all the multivariate analyses, aggressive masculinity is directly associated with more use of all three substances. Affective femininity is inversely related to the amount of lifetime alcohol and cigarette use, and submissive femininity is inversely related to alcohol and marijuana use.

Table 2. Regression Predicting Lifetime Amount of Alcohol, Cigarette and Marijuana Use.

| Lifetime alcohol use | Lifetime cigarette use | Lifetime marijuana use | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | III | III | I | II | III | III | III | I | II | III | III | III | |

| Less acculturated Mexican American | More acculturated Mexican American | Non-Latinos | Less acculturated Mexican American | More acculturated Mexican American | Non-Latinos | Less acculturated Mexican American | More acculturated Mexican American | Non-Latinos | |||||||

| b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | |

| Less acculturated Mexican American | −0.104 | −0.039 | −0.148** | −0.101 | −0.401*** | −0.336*** | |||||||||

| More acculturated Mexican American | 0.242*** | 0.261*** | 0.058 | 0.070 | −0.006 | 0.012 | |||||||||

| Age | 0.067* | 0.058 | 0.134 | 0.042 | 0.065 | 0.097*** | 0.087** | 0.159** | 0.093** | −0.073 | 0.103*** | 0.098*** | 0.088** | 0.099** | 0.031 |

| School lunch | −0.270*** | −0.220*** | −0.252 | −0.160 | −0.249** | −0.095 | −0.057 | −0.655*** | −0.119 | 0.158 | −0.102 | −0.057 | −0.359*** | −0.153* | 0.102 |

| Usual grades | −0.065*** | −0.061*** | −0.016 | −0.073*** | −0.053* | −0.085*** | −0.081*** | −0.056* | −0.076*** | −0.113*** | −0.082*** | −0.082*** | −0.053*** | −0.079*** | −0.109*** |

| Gender: F = 0; M = 1 | 0.113*** | 0.035 | 0.005 | 0.076 | −0.003 | 0.066 | −0.000 | 0.028 | 0.042 | −0.107 | 0.116*** | 0.055 | −0.028 | 0.058 | 0.136 |

| Assertive masculinity | −0.029 | 0.107 | −0.051 | −0.077 | 0.012 | 0.066 | 0.022 | −0.160 | 0.003 | −0.006 | −0.012 | −0.115 | |||

| Aggressive masculinity | 0.143*** | 0.086 | 0.175** | 0.296** | 0.129*** | 0.123 | 0.162*** | 0.385*** | 0.161*** | 0.104** | 0.194*** | 0.321*** | |||

| Affective femininity | −0.087*** | −0.130 | −0.056 | −0.181 | −0.102*** | −0.094 | −0.079 | −0.168 | −0.034 | −0.006 | −0.023 | −0.115 | |||

| Submissive femininity | −0.066** | 0.011 | −0.035 | −0.050 | 0.011 | 0.073 | 0.055 | −0.065 | −0.067*** | −0.060 | −0.089** | 0.028 | |||

| Gender × Assertive masculinity | −0.138 | 0.012 | 0.097 | 0.013 | 0.000 | 0.139 | 0.076 | 0.006 | 0.218 | ||||||

| Gender × Aggressive masculinity | 0.092 | −0.053 | −0.260* | 0.049 | −0.089 | −0.323** | −0.035 | −0.015 | −0.290** | ||||||

| Gender × Affective femininity | −0.062 | 0.007 | 0.103 | −0.056 | −0.006 | 0.076 | 0.054 | −0.014 | 0.059 | ||||||

| Gender × Submissive femininity | −0.108 | −0.089 | 0.050 | −0.080 | −0.080 | 0.084 | 0.054 | 0.053 | −0.166 | ||||||

| Intercept | 1.105*** | 1.081*** | 1.059*** | 1.266*** | 1.149*** | 0.709*** | 0.696*** | 1.144*** | 0.803*** | 0.622*** | 0.571*** | 0.542*** | 0.529*** | 0.644*** | 0.410*** |

| N | 1318 | 1310 | 223 | 863 | 222 | 1319 | 1312 | 223 | 866 | 221 | 1318 | 1310 | 222 | 865 | 221 |

| R2 (Adjusted) | 0.070 | 0.094 | 0.020 | 0.070 | 0.046 | 0.060 | 0.080 | 0.095 | 0.061 | 0.098 | 0.114 | 0.143 | 0.106 | 0.099 | 0.128 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Results shown in Table 2 are not presented separately for boys and girls. These equations indicate that the impact of the four gender identity indexes on lifetime use of alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana is in the same direction and of similar magnitude for boys as well as for girls. Moreover, in regression equations with gender-by-gender-identity interaction terms (also not presented for the combined sample) to determine if there are statistically significant differences between boys and girls in the predictive power of the four gender identity indexes, none of the differences were statistically significant (p < .05). The gender interaction effects showed a significant impact on outcomes only within certain ethnic groups, as shown in the separate equations presented in Table 2 for less and more acculturated Mexican Americans, and for non-Latinos (Model III).

Before discussing these interaction effects it is important to note some main effects of ethnicity/acculturation. In Model I, the less acculturated Mexican Americans display a consistent tendency to have used cigarettes and marijuana less than the non-Latinos, while more acculturated Mexican Americans report higher usage of alcohol than the non-Latinos. For less acculturated Mexican Americans, lower use rates than non-Latinos also appear to be due to differences in their gender identities, as indicated by the substantial reductions in the size of the effects when gender identity is controlled in Model II. Controlling other factors, the largest differences in lifetime drug use do not then appear between boys and girls, nor between Mexican Americans and non-Latinos, but between more and less acculturated Mexican American adolescents.

Results separated by ethnicity/acculturation (Model III) provide additional insights. These equations include the gender-by-gender identity interactions, which are scored to indicate how much the effects of gender identity differ for boys compared to girls. Once again there are no indications that assertive masculinity affects lifetime drug use for either gender in any ethnic/acculturation group. The weak effects of affective femininity for the overall sample are reduced to nonsignificance when separate ethnic/acculturation groups are examined. Submissive femininity appears only as a significant protector against marijuana use for the more acculturated Mexican Americans. Aggressive masculinity, however, is directly related to higher amounts of use of all three substances for the more acculturated Mexican Americans as well as the non-Latinos. It is also linked to more marijuana use by the less acculturated Mexican Americans. The effects of aggressive masculinity are much greater for the non-Latinos than the other groups. In a consistent and surprising pattern across the three substances, the gender interaction effects, which are significant only for non-Latinos, show that aggressive masculinity is a more powerful risk factor for drug use among non-Latino girls than among non-Latino boys.

Several of the control variables are related to lifetime drug use, at times in unexpected ways. Higher grades are consistently associated with less use of all three substances. Older respondents report more lifetime use of cigarettes and marijuana, although not among the non-Latino respondents, and more alcohol use for the sample as a whole. Lower income students—participants in the Federal school lunch program—report less use of alcohol among all the respondents combined, but this effect is significant only for the non-Latinos. For cigarette and marijuana use, however, only less acculturated Mexican Americans from lower income families report significantly less use.

Three more drug related outcomes are detailed in Table 3: a composite index of the frequency and amount of alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use in the last 30 days, age of first initiation into use of one of those substances, and a factor score measuring strength of espousal of anti-drug norms. As seen in Table 2 the less acculturated Mexican Americans report more desirable outcomes than non-Latinos, at least partially as a result of their different gender identity scores. More acculturated Mexican Americans, rather than falling “in between” the other two groups, report more recent alcohol use and even weaker anti-drug norms than reported by non-Latinos. Boys overall appear more at risk than girls of early drug use and weak anti-drug norms when gender labels are used as predictors without controlling for gender identity. There are no overall gender differences in recent drug use, and the apparently weaker anti-drug norms of boys can be attributed more to differences in gender identity than to gender by itself. Age of initiation is another matter: among users, boys begin use earlier than girls, even when gender identity is included as a predictor.

Table 3. Regression Recent Substance Use, Age of Initiation, and Adherence to Anti-Drug Norms.

| Last 30 Day Alcohol/Cigarette/Marijuana Use | Age of Drug Initiation (Users Only) | Anti-Drug Norm Index | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | III | III | I | II | III | III | III | I | II | III | III | III | |

| Less acculturated Mexican American | More acculturated Mexican American | Non-Latinos | Less acculturated Mexican American | More acculturated Mexican American | Non-Latinos | Less acculturated Mexican American | More acculturated Mexican American | Non-Latinos | |||||||

| b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | b | |

| Less acculturated Mexican American | −0.108*** | −0.053 | 0.658** | 0.452 | 0.300*** | 0.174** | |||||||||

| More acculturated Mexican American | 0.041 | 0.058* | −0.006 | −0.070 | −0.170** | −0.205*** | |||||||||

| Age | 0.053** | 0.047** | 0.030 | 0.062** | −0.037 | 0.204 | 0.246* | 0.811* | 0.116 | 0.610 | −0.118*** | −0.102** | −0.208** | −0.131** | 0.158 |

| School lunch | −0.087** | −0.046 | −0.310** | −0.078 | 0.035 | 0.461* | 0.283 | −0.001 | 0.411 | −0.143 | 0.312*** | 0.209*** | 0.582* | 0.262** | −0.001 |

| Usual grades | −0.050*** | −0.048*** | −0.050*** | −0.046*** | −0.054*** | −0.020 | −0.036 | −0.212 | −0.032 | 0.035 | 0.125*** | 0.104*** | 0.073** | 0.119*** | 0.065* |

| Gender: F = 0; M = 1 | 0.019 | −0.040 | −0.113** | −0.026 | −0.021 | −0.769*** | −0.626*** | −1.555** | −0.553*** | −0.383 | −0.124** | 0.040 | 0.034 | 0.035 | 0.108 |

| Assertive masculinity | −0.006 | 0.014 | −0.001 | −0.164** | 0.201 | −0.569 | 0.035 | 0.146 | 0.096*** | 0.104 | 0.099 | 0.358*** | |||

| Aggressive masculinity | 0.128*** | 0.156*** | 0.125*** | 0.269*** | −0.494*** | 0.469 | −0.538*** | −0.625 | −0.343*** | −0.311*** | −0.361*** | −0.392*** | |||

| Affective femininity | −0.055*** | −0.070 | −0.063* | −0.045 | −0.008 | 0.951 | 0.021 | −0.993** | 0.184*** | 0.187 | 0.164*** | 0.360*** | |||

| Submissive femininity | −0.043*** | −0.065 | −0.049* | −0.133* | 0.241** | −0.658 | 0.105 | 0.713 | 0.067** | 0.151* | 0.075 | 0.023 | |||

| Gender × Assertive masculinity | 0.038 | 0.013 | 0.125 | 0.756 | 0.150 | 0.940 | −0.096 | −0.079 | −0.118 | ||||||

| Gender × Aggressive masculinity | −0.055 | −0.003 | −0.199** | −0.802 | 0.007 | −0.143 | −0.014 | 0.039 | 0.022 | ||||||

| Gender × Affective femininity | 0.035 | 0.005 | −0.011 | −0.520 | −0.057 | 0.893 | −0.021 | 0.054 | −0.247 | ||||||

| Gender × Submissive femininity | 0.026 | 0.027 | 0.122 | 0.252 | 0.373 | −0.156 | −0.100 | −0.047 | 0.085 | ||||||

| Intercept | 0.336*** | 0.311*** | 0.564*** | 0.394*** | 0.258*** | 10.146*** | 10.328*** | 11.704*** | 10.120*** | 10.574*** | −0.176** | −0.130 | −0.320 | −0.380*** | −0.053 |

| N | 1324 | 1316 | 223 | 869 | 222 | 817 | 813 | 99 | 577 | 135 | 1272 | 1267 | 206 | 844 | 215 |

| R2 (Adjusted) | 0.065 | 0.117 | 0.122 | 0.094 | 0.116 | 0.033 | 0.055 | 0.083 | 0.044 | 0.045 | 0.120 | 0.218 | 0.200 | 0.188 | 0.186 |

p < .001.

p < .01.

p < .05.

Also as in the previous table, aggressive masculinity is consistently associated with undesirable drug outcomes, once again for girls and for boys (separate results not shown), and for most of the ethnic/acculturation groups. In the case of recent drug use aggressive masculinity also appears to be a stronger risk for non-Latino girls than boys, as shown by the gender interaction effects. The other three gender identity indexes are more selectively and much less powerfully related to the three outcomes. Assertive masculinity is directly related to stronger anti-drug norms and inversely related to recent drug use, but only for non-Latinos. Both the affective femininity and submissive femininity indexes generally predict more desirable outcomes, but in each case there are interesting contradictions. Affective femininity has a much stronger salutary effect among non-Latinos than the others in delaying initiation into drug use and strengthening anti-drug norms. Submissive femininity shows the most complex pattern across ethnic/acculturation groups: as a protective factor against recent drug use among acculturated Mexican Americans and especially among non-Latinos and a reinforcer of anti-drug norms among less acculturated Mexican Americans. Although submissive femininity is associated with later initiation into drug use overall, this appears to be due to non-Latinos and masks a nonsignificant effect operating in the opposite direction for less acculturated Mexican Americans.

In addition to the models presented in Tables 2 and 3, as well as the models with gender interaction effects which are discussed above but not presented, we investigated several other models which are not presented. One set examined the impact of the gender identity indexes on all six drug outcomes without controlling for gender label. These results were essentially the same as the presented models with controls for gender label, indicating that gender identity influences drug outcomes independently of gender labels.

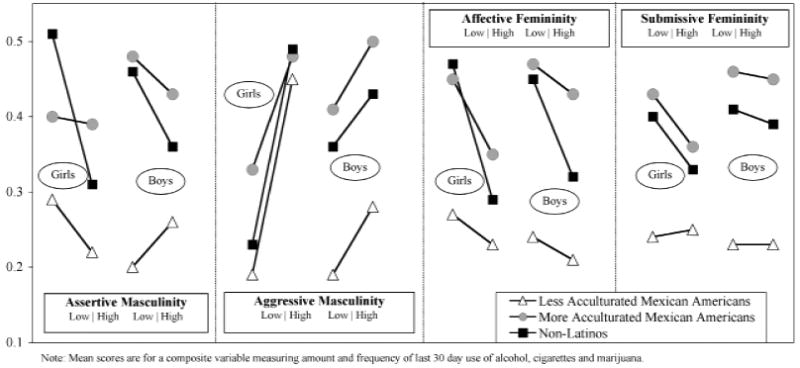

To illustrate some of the complexities in the interrelationships among gender identity, gender, and ethnicity as predictors of adolescent drug use in the study population, Figure 2 displays mean scores on a composite scale measuring recent drug use: both frequency and amount of alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use in the last 30 days. The six component items for this measure were log transformed and then averaged, forming a highly reliable scale (Cronbach's α = .87). The chart is divided into four sections, each reporting a series of means on the drug use scale and comparing paired groups of respondents who scored below (low) or above (high) the mean on each of the four gender identity measures. Within each of these sections, drug use means are presented by gender, and within gender, by ethnicity/acculturation. Lines slanting upward (left to right) indicate higher drug use among those with higher scores on that gender identity index. At the far left, for example, we see that mean drug use is lower among girls with relatively high scores on the assertive masculinity index. The direction of the difference between low and high assertive masculinity is the same for all girls regardless of ethnicity, but the size of the difference is particularly large among the non-Latino girls. Also notable is that the mean drug use for less acculturated (i.e., Spanish-language dominant) Mexican American girls hovers below that of the other ethnicity/acculturation groups. The same patterns are also seen among boys, but with one exception: less acculturated Mexican American boys report higher mean drug use when they have relatively high scores on the assertive masculinity index.

Figure 2.

Recent drug use (means) by gender identity scores (low vs. high), gender, and ethnicity.

There are also consistent patterns across Figure 2 showing the impact of the other gender identity indexes on drug use. All groups, regardless of gender or ethnicity/acculturation, report more recent drug use if they have higher rather than lower scores on the aggressive masculinity index. These differences are particularly striking among the girls, and especially among the Mexican American girls, both the more and less acculturated. Indeed, the girls with relatively high aggressive masculinity scores are the only group as shown in Figure 2 where no ethnic differences are clearly suggested.

The general trends for the remaining two sets of gender identity measures are the same: those with lower scores on affective femininity or on submissive femininity tend to report more recent drug use. However, these differences appear most clearly among non-Latinos and more acculturated Mexican Americans, not among the less acculturated, and they appear somewhat more clearly among girls than boys.

Figure 2 illustrates several of the findings from the regression analyses. First, less acculturated Mexican American students tend to report less drug use than other groups, and, with the exception of aggressive masculinity, gender identity is less of a factor in drug use for them. Second, patterns of drug use for more acculturated Mexican Americans resemble those of non-Latinos more than those of their less acculturated Mexican American counterparts. Third, gender differences are minimal or absent after controlling for gender identity: girls and boys from the same ethnic/acculturation groups who also have similar gender identity scores tend to report similar levels of drug use. Finally, aggressive masculinity is a consistently and strongly implicated factor in higher drug use regardless of gender and ethnicity.

Discussion

Our findings follow national adolescent drug use trends (Kann et al., 2000). Alcohol was identified by the students as their drug of choice, followed by cigarettes and marijuana, with Mexican American respondents reporting more alcohol use than students of other ethnicities. Boys reported more lifetime use of alcohol and marijuana than girls did, but these differences did not persist when gender identity indexes were added as predictors. Except for the earlier age of initiation into drug use reported by male users, gender differences in drug outcomes narrowed to nonsignificance. Gender alone is not consistent nor it is a strong predictor of most drug use outcomes. The findings suggest that it is gender identity rather than gender that becomes a risk or protective factor for boys and girls of different ethnic/acculturation backgrounds.

Gender alone had limited explanation power, while gender identity—often regardless of gender—was a better predictor of drug use behaviors and norms. The great majority of the students reported high scores for both assertive masculinity and affective femininity. However, while boys overall reported the highest scores for aggressive masculinity, girls overall scored higher than boys on both dimensions of femininity and on the assertive masculinity dimension as well (the latter is attributable mostly to non-Latino girls). The alignment of Mexican American students overall on the gender identity measures was not significantly different than that of their non-Latino counterparts. Once distinguished by Spanish language dominance, however, the less acculturated Mexican American students reported lower aggressive masculinity scores than non-Latinos. Less acculturated Mexican American girls reported both the lowest aggressive masculinity scores and the highest submissive femininity scores. The less acculturated Mexican American boys, in particular, did not exhibit the expected polarized approach to gender identity: they had the lowest aggressive masculinity scores of all the boys. Moreover, even though the least acculturated Mexican American girls did display markedly higher submissive femininity scores, this did not generally put them at great risk in the drug outcomes examined in the study. Although the potentially negative impact of such submissiveness is reflected in the earlier age of initiation reported by the less acculturated Mexican American girls who had started using drugs—perhaps reflecting difficulty in refusing drug offers from male peers and family members—such drug use was much less common overall than among other girls. These particular findings are consistent with reservations that have been raised about the stereotypical interpretation of machismo and marianismo as invariably leading to undesirable outcomes (Falicov, 1996; Neff, 2001). It suggests that some aspects of culturally prescribed gender roles can have a protective effect against drug use behaviors and attitudes, possibly for both girls and boys.

Another group whose behavior appears to contradict stereotypes are the students from lower income families (receiving free and reduced-price school lunches) who often reported less drug use than higher income students. Further investigation is indicated to address whether this may be due to a preponderance of single-mother-headed families in this group. Since women tend to drink less frequently and less heavily than men do, and espouse more conservative alcohol norms, children living in homes where the only parent is a women would be exposed to less male drinking (Johnson & Johnson, 1999). They would also presumably be exposed to fewer role models for aggressive masculinity, and might be expected to assume childcare and household duties more often, perhaps strengthening their adoption of gender identities stressing protective aspects of assertive masculinity and affective femininity.

As in previous studies involving similar populations (Kulis et al., 2002), aspects of masculine gender identity focusing on dominance and control of others were most clearly linked to drug outcomes: more lifetime and recent use of alcohol, cigarettes and marijuana, earlier initiation into use, and weaker anti-drug norms. These results were similar for boys and girls overall. Aggressive masculinity, however, showed stronger undesirable impacts on substance use outcomes for non-Latinos than for the more and less acculturated Mexican Americans, and in several instances its impact was significantly more deleterious for non-Latino girls than for non-Latino boys. It is possible, and worthy of further study, that the narrowing of the gender gap in adolescent drug use is attributable, at least in part, to the selective erosion of stereotypical gender identities. Figuratively, the results suggest that “girls are acting like boys” rather than that some form of “gender blending” is occurring. It may be seen as alarming that traits commonly thought to be reserved to risk-taking adolescent males now register as potent risk factors for girls as well.

The results also speak to protective aspects of gender identity as well. Assertive masculinity, which characterized the non-Latinos girls more than any other group, appeared to have a buffering effect only in mitigating recent drug use and strengthening anti-drug norms. Although the effect applied to both boys and girls, it also applied only to non-Latinos. Both affective femininity and submissive femininity had a typically similar protective effect against drug use regardless of gender, but the various significant effects applied more often to acculturated Mexican Americans and non-Latinos than to less acculturated Mexican Americans. This raises the possibility that both of the femininity indexes may be proxies for another protective factor, such as family-centeredness, which may buffer against negative peer influences (Huselid & Cooper, 1992). A small, but important finding in the other direction is the earlier initiation into drug use (among those who are users) of less acculturated Mexican American girls with the highest submissive femininity scores. This is worthy of follow-up to see whether this group, though perhaps more generally insulated from drug offers, is less capable or confident in resisting such offers, particular from more powerful males in their social networks, such as boyfriends, brothers, and cousins (Moon et al., 1999).

In summary, these findings indicate that among Mexican American pre-adolescents affective femininity and submissive femininity have a protective effect against drug use for both boys and girls, but this effect is stronger among those who are more acculturated. Aggressive masculinity is a risk factor for both less and more acculturated Mexican American pre-adolescents, but even more so for non-Latinos. To be a boy or a girl by itself does not predict drug use well; gender identity surfaces as a much stronger predictor. But the adoption of different dimensions of gender identity, and how these relate to drug use appears to be mediated in important ways by ethnicity and acculturation. These findings hold for Mexican American students who identify with positive and negative traits of culturally-based gender archetypes such as machismo and marianismo. Future research is merited on the question of how acculturation affects their adoption of the more fluid gender roles of majority culture, and how this process relates to drug use.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse grants funding the Drug Resistance Strategies Project (5 R01 DA05629-07) and the Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Consortium (SIRC) at Arizona State University (R24 DA13937-01).

References

- Alaniz ML, Treno AJ, Saltz RF. Gender, acculturation, and alcohol consumption among Mexican Americans. Substance Use & Misuse. 1999;34(10):1407–1426. doi: 10.3109/10826089909029390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antill JK, Cunningham JD, Russell G, Thompson NL. An Australian sex-role scale. Australian Journal of Psychology. 1981;33:169–183. [Google Scholar]

- Arrellano CM, Chavez EL, Deffenbacher JL. Alcohol use and academic status among Mexican American and white non-Hispanic adolescents. Adolescence. 1998;33:751–760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baca Zinn M. Chicano men and masculinity. Journal of Ethnic Studies. 1982a;10:29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Baca Zinn M. Mexican-American women in the social sciences. Signs. 1982b;8:259–272. [Google Scholar]

- Bem SL. The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1974;42:155–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez EL, Swaim RC. An epidemiological comparison of Mexican-American and white non-Hispanic 8th- and 12th-grade students' substance use. American Journal of Public Health. 1992;82:445. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.3.445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan JE. Gender differences in alcohol involvement in children and adolescents: A review of the literature. In: Howard JM, Martin SE, Mail PD, Hilton ME, Taylor ED, editors. Women and alcohol: Issues for prevention research. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 1996. pp. 133–161. NIH Publication No. 96–3817. [Google Scholar]

- Falicov CJ. Love and gender in the Latino marriage. System Familie. 1996;9(2):60–66. [Google Scholar]

- Felix-Ortiz M, Newcomb MD. Vulnerability for drug use among Latino adolescents. Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27(3):257–280. [Google Scholar]

- Flannery DJ, Vazsonyi AT, Torquati J, Fridrich A. Ethnic and gender differences in risk for early adolescent substance use. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1994;23:195–213. [Google Scholar]

- Gil RM, Vazquez CI. The Maria paradox. New York: Putnam; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Wagner EF, Vega WA. Acculturation, familism, and alcohol use among Latino adolescent males: Longitudinal relations. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(4):443–458. [Google Scholar]

- Goldwert M. Machismo and conquest: The case of Mexico. Lanham, MD: University Press of America; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Helgeson VS. Relation of agency and communion to well-being: Evidence and potential explanations. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:412–428. [Google Scholar]

- Howard MO, Walker RD, Walker PS, Cottler LB, Compton WM. Inhalant use among urban American Indian youth. Addiction. 1999;94(1):83–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.941835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado AL. When strangers met: Sex and gender on three frontiers. Frontiers. 1996;17(3):52–75. [Google Scholar]

- Huselid RF, Cooper ML. Gender roles as mediators of sex differences in adolescent alcohol use and abuse. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1992;33:348–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DW, Johnson RT. Promoting safe educational and community environments. In: Reynolds A, Walberg HJ, editors. Promoting positive outcomes. Issues in children's and families lives. Washington, DC: Child Welfare League of America; 1999. pp. 161–196. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Yamaguchi K, Chen K. Stages of progression in drug involvement from adolescence to adulthood: Further evidence for the Gateway Theory. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1992;53:447–457. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1992.53.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB. Ethnic differences in drug use: Patterns and paradoxes. In: Botvin GJ, Schinke S, Orlandi MA, editors. Drug abuse prevention with multiethnic youth. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995. pp. 81–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB, Wu P. The contribution of mothers and fathers to the intergenerational transmission of cigarette smoking in adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1995;5(2):225–252. [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Kinchen SA, Williams BI, Ross JG, Lowry R, Grunbaum JA, Kolbe LJ. Youth risk behavior surveillance-United States, 1999. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly. 2000;49(5):1–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karniol R, Gabay R, Ochion Y, Harari Y. Is gender or gender-role orientation a better predictor of empathy in adolescence? Sex Roles. 1998;39:45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Kulis S, Marsiglia FF, Hecht ML. Gender labels and gender identity as predictors of drug use among ethically diverse middle school students. Youth and Society. 2002;33:442–475. [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Cantu MA, Medina-Mora MA, Gutiérrez CE. Relationship between masculinity and femininity in drinking in alcohol-related behavior in a general population sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1990;26:45–54. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(90)90082-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light H. Sex differences in indicators of well being in adolescents. Psychological Reports. 2000;87:531–534. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2000.87.2.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Myers M. Masculinity, femininity, and androgyny: A methodological and theoretical critique. Sex Roles. 1986;14:397–430. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Hecht ML. Ethnic labels and ethnic identity as predictors of drug use among middle school students in the southwest. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11(1):21–48. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Holleran L. I've learned so much from my mother: An ethnography of a group of Chicana high school students. Social Work in Education. 1999;21(4):220–237. [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Waller M. Language preference and drug use among Southwestern Mexican American middle school students. Children & Schools. 2002;25(3):145–158. [Google Scholar]

- McCreary DR, Newcomb MD, Sadava SW. Dimensions of the male gender role: A confirmatory analysis in men and women. Sex Roles. 1998;39:81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JC, Kleber HD, Shwartz M, Liu H, Lewis SR. Cigarettes, alcohol, marijuana, other risk behaviors, and American youth. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1999;56(3):205–212. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00034-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirandé A. A reinterpretation of male dominance in the Chicano family. Family Coordinator. 1979;28:473–479. [Google Scholar]

- Mirandé Alfredo. The Chicano experience: An alternative perspective. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Moon DG, Hecht ML, Jackson KM, Spellers R. Ethnic and gender differences and similarities in adolescent drug use and the drug resistance process. Substance Use and Misuse. 1999;34:1059–1083. doi: 10.3109/10826089909039397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff JA. A confirmatory factor analysis of a measure of machismo among Anglo, African American, and Mexican male drinkers. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2001;23(2):171–188. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Bentler P. Substance use and ethnicity: Differential impact of peer and adult models. Journal of Psychology. 1986;120(1):83–95. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1986.9712618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orozco S, Lukas S. Gender differences in acculturation and aggression as predictors of drug use in minorities. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;59(2):165–172. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perea A, Slater MD. Power distance and collectivist/individualist strategies in alcohol warning: Effects by gender and ethnicity. Journal of Health Communication. 1999;4(4):295–310. doi: 10.1080/108107399126832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randolph VM, Stroup-Benam C, Black SA, Markides KS. Alcohol use among Cuban-Americans, Mexican Americans, and Puerto Ricans. Alcohol Health & Research World. 1998;22(4):265–269. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicow K, Soler R, Braithwaite RL, Ahluwalia JS, Butler J. Cultural sensitivity in substance use prevention. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(3):271–290. [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardelli LA, Williams RJ. Desirable and undesirable gender traits in three behavioral domains. Sex Roles. 1995;33:637–655. [Google Scholar]

- Russell G, Antill JK. An Australian sex-role scale: Additional psychometric data and correlations with self-esteem. Australian Psychologist. 1984;19:13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sarigiani PA, Ryan L, Petersen AC. Prevention of high-risk behaviors in adolescent women. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1999;25(2):109–119. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(99)00015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schinke SP, Tepavac L, Cole KC. Preventing substance use among Native American youth: Three year results. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25(3):387–397. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater JM, Guthrie BJ, Boyd CJ. A feminist theoretical approach to understanding health of adolescent females. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;28:443–449. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00207-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens EP. The prospects for a Women's Liberation movement in Latin America. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1973;35:313–321. [Google Scholar]

- Surrey JL. The “self-in-relation”: A theory of women's development. In: Jordan JV, Kaplan AG, Miller JB, Stiver IP, Surrey JL, editors. Women's growth in connection: Writings from the Stone Center. New York: The Guilford Press; 1991. pp. 51–66. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas BS. A path analysis of gender differences in adolescent onset of alcohol, tobacco and other drug use (ATOD), reported ATOD use and adverse consequences of ATOD use. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 1996;15(1):33–52. doi: 10.1300/J069v15n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wycoff CS. The García family: Using a structural systems approach with an alcohol-dependent family. Family Journal. 2000;8(1):47–57. [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Williford WR. The age of alcohol onset and alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use patterns: An analysis of drug-use progression of young adults in New York State. International Journal of the Addictions. 1992;27(11):1313–1323. doi: 10.3109/10826089209047353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]