Abstract

A randomly selected cross-sectional survey was conducted with 880 youth (16 to 24 years) in Nha Trang City to assess relationships between alcohol consumption and sexual behaviors. A timeline followback method was employed. Chi-square, generalized logit modeling and logistic regression analyses were performed. Of the sample, 78.2% male and 56.1% female respondents ever consumed alcohol. Males reporting sexual behaviors (vaginal, anal, oral sex) had a significantly higher calculated peak BAC of 0.151 compared to 0.082 for males reporting no sexual intimacy (p < .0001). Females reporting sexual behaviors had a peak BAC of 0.072 compared to 0.027 for those reporting no sexual intimacy (p = .016). Fifty percent of (33/66) males and 30.4% (7/23) females report event specific drinking and engagement in sexual behaviors. Males reporting 11+ drinks in 30 days had more sexual partners than those reporting 1 to 10 drinks (p = .037). Data suggest different physical and psychosocial mediators between alcohol consumption and sexual behaviors by gender.

Keywords: adolescent, alcohol use, sexual behaviors

Introduction

With increasing reported rates of HIV/AIDS throughout Asia (Detels, 2004), there is a need to understand factors associated with engagement in sexual behaviors within Asian cultures including the potential role of alcohol consumption. We explore data collected in Nha Trang, Viet Nam on youth aged between 16 and 24 years and their reported engagement in sexual behaviors, as related to quantities of alcohol consumed and reported use of alcohol prior to specific sexual episodes.

In Viet Nam, between 2000 and 2006, prevalence of HIV/AIDS among 15 to 49 year olds has increased from 0.27% (an estimated 122,000 cases) to 0.53% (an estimated 280,000 cases). However, in some areas of the country (the North East and Ho Chi Minh City), prevalence is currently estimated at more than 1.2% (Ministry of Health Viet Nam, n.d.). As elsewhere, HIV/AIDS disproportionately affects young adults with 63% of cases among 20 to 29 year olds (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS [UNAIDS], 2002). While official information regarding the HIV epidemic emphasizes prevalence among IDUs and female sex workers (FSW), national-level statistics on reported cases in 2003 indicate 48% of cases were outside of these two groups (Hien, Long, & Huan, 2004). At this time, approximately 2.3 males are infected for each female, however this ratio is decreasing as heterosexual transmission becomes more common. Without stronger prevention programs, an estimated 40,000 individuals per year will contract HIV in the coming years (Ministry of Health Viet Nam, n.d.). Other reproductive health issues for adolescents and young adults include other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unwanted pregnancy. The World Health Organization (2000) estimates one million new cases of STIs in Viet Nam every year; however, with no reporting requirement for private health care facilities, actual data is difficult to access. Viet Nam also has one of the world’s highest abortion rates with an estimated 83.3 per 1,000 women receiving abortions including 300,000 abortions performed annually for women below 19 years (Alan Guttmacher Institute, 1999; EC/UNFPA, 1999). Like treatment seeking for STIs, however, many abortions are performed in private clinics and are not reported to the local government health department.

Viet Nam has undergone multiple economic and social reforms, most notably since 1986 with the establishment of a more liberalized market system (“Doi Moi”; Kolko, 1997). The country has experienced a significant decrease in economic and political isolation, and has moved rapidly toward inclusion in the global economy. These changes have resulted in the emergence of a growing middle class and a reduction in the poverty rate from 60% to 20% over the past 15 years (World Bank, 2007) as well as increasing economic disparity between income groups and regions.

While many of these economic changes have been received with enthusiasm by the government and the local populace, resultant social changes associated with the “open door” policies have come under scrutiny and criticism (Kaljee, Tho, Hung, & Diep, 2008; Lerdboon et al., 2008). In particular, the current generation of adolescents and young adults has become more independent with increasing access to goods and services, for example, mobile phones, motorbikes, and information through the Internet and satellite television. Young men and women socialize together and interact in ways which are creating conflicts between traditional and modern gender roles as young women occupy public spaces previously reserved for men. At the center of these contradictions are issues around sexuality and sexual relations. Traditionally men are perceived as self-reliant and risk-taking is acceptable and even encouraged. Women on the other hand are responsible and have to maintain their purity and innocence for marriage. These social models often conflict with the day-to-day interactions and relationships between young men and women resulting in stigmatization of sexual behaviors particularly for women (Kaljee et al., 2007).

Limited data are available on sexual behaviors among Vietnamese adolescents and young adults. A computer-assisted self-interview for Ha Noi youth 15 to 24 years old revealed 17.1% of males and 4.5% females reporting engagement in premarital sex (Le, Blum, Magnani, Hewett, & Do, 2006). In statistics from a 2006 survey, 21% of unmarried men (aged 15 to 24 years) stated they had engaged in sex with a “casual partner” in the past 12 months (UNAIDS, 2006). Other survey research with older adolescents and young adults (aged 18 to 29 years) indicated 43.3% of sexually active youth report engaging in premarital sexual activity. In this same survey, 56.7% of sexually active males report multiple lifetime partners compared to only 9.2% sexually active females reporting multiple partners. Also among sexually active males, 30.8% respondents reported having sex with a commercial sex worker (Duong et al., 2008).

Recent research in Asia show high rates of alcohol consumption among adolescents and young adults. Among a sample of 1,040 youth in Grades 6, 8, and 10 in Beijing, China, approximately 70% reported prior alcohol consumption. Males were significantly more likely to drink alcohol than females, although 61% of females reported prior use of alcohol (Li, Fang, Stanton, Feigelman, & Dong, 1996). Data from a study at sixty 4-year colleges in South Korea indicated that 42.3% of students surveyed had an alcohol use disorder. Students not living with parents or relatives, heavy alcohol use among parents, and being male were factors associated with alcohol use disorder (Chun & Sohn, 2005). Studies in Japan reveal an increasingly early onset of alcohol consumption among adolescents, increasing rates of drinking among 13 to 17 year olds, and higher percentages of females drinking one or more times per week (Desapriya, Iwase, & Shimizu, 2002; Suzuki et al., 2003). In the Survey Assessment of Vietnamese Youth (SAVY) conducted in 42 provinces, 69% of young men and 28.1% young women (aged 14 to 25 years) ever consumed alcohol (Ministry of Health Viet Nam, 2003).

Literature on alcohol consumption and sexual risk behavior research disclose multifaceted and sometimes contradictory outcomes. In a literature review, Coleman and Cater (2005) discuss “global correlation studies,” which associate general alcohol consumption and sexual behaviors as compared to “event-specific” studies, which ask about consumption patterns in relationship to a defined sexual episode (e.g., last sexual encounter). In many studies, the relationship between alcohol and sexual behaviors is more likely part of a pattern of risk-taking behaviors than a direct causal mechanism. Thus, much research on adolescents living in Western countries has focused on possible mediating factors, which might affect decisions to engage in sexual behaviors after consuming alcohol.

Alcohol outcome expectancy theory (Marlatt & Rohsennow, 1980; Derman, Cooper, & Agocha, 1998) postulates that cognitive beliefs, including those related to sexual inhibitions and/or risk taking, are strong influences in decision making and can influence behaviors during alcohol consumption. Alcohol myopia theory suggests that the causal effect between alcohol and sexual risk behaviors is a result of impaired cognitive functioning during intoxication, which prevents individuals from processing all information from the environment (Cooper, 2002; George & Stoner, 2000). Other factors associated with alcohol consumption and sexual risk behaviors include self-esteem and sensation-seeking (Guilette & Lyons, 2006; Thompson, Kao, & Thomas, 2005). In addition to these psychological models, ethnographic and qualitative studies have contributed data on meanings of alcohol consumption across cultures and the role of alcohol in personal and group identities including gender (Gefou-Madianou, 1992). This research has contributed to understanding cultural variations in the social norms and expectancies of alcohol consumption (Douglas, 1987; Room, Agar, Beckett, Bennett, & Casswell, 1984).

In a survey of young adult migrant populations in Beijing and Nanjing, China, among both men and women respondents, there were significant relationships between intoxication in the past 30 days and engagement in premarital sex, multiple partners, and engagement in transactional sex (Lin et al., 2005). In a cross-sectional survey among Thai vocational students, alcohol consumption was a part of the predictive model for inconsistent or noncondom use among sexually active respondents (Thato, Charron-Prochownik, Dorn, Albrecht, & Stone, 2003). Among university students in Ha Noi and Ho Chi Minh City, 62% of females and 70% of males feel that alcohol “facilitates” casual sex (World Health Organization, 2003). Ongoing research among adolescents and young adults living in the current research site of Khanh Hoa Province suggests an association between alcohol consumption and engagement in sexual behaviors (Kaljee et al., 2005; Tho, Singhasivanon, Kaewkungwai, Kaljee, & Charoenkul, 2007). Qualitative data collected from 2002 to 2005 further suggest that consumption of alcohol is perceived as closely associated with engagement in sexual behaviors, and that in the conservative culture of Viet Nam alcohol may provide a means of decreasing inhibitions as well as an excuse for socially taboo behaviors (Kaljee et al., 2007; Kranker, 2006).

Method

Research Site

The research was conducted in six central city and periurban communes within Nha Trang, Viet Nam. Nha Trang is the provincial capital of Khanh Hoa Province, which is located in south-central coastal Viet Nam. Industries within the province include tourism, agriculture, fish and shrimp farming, fishing, shipping, and manufacturing. There are 137 communes in Khanh Hoa Province including 27 communes in Nha Trang City. Commune sizes range from about 7,000 to 20,000 individuals. The population of Nha Trang is approximately 323,000. Nha Trang is primarily an urban area with some semirural communes on the periphery of the city. It is a popular beach resort for both domestic and foreign tourists, with tourism as its primary industry. Recent development in the city has created rapid changes in its landscape, as high-rise luxury hotels begin to line the beachfront. These changes have increased prices for land and housing, displaced residents, and increased the influx of domestic migrant laborers as construction workers and service providers.

Ethical Assurances

The University of Maryland Baltimore School of Medicine, Institutional Review Board and the Khanh Hoa Provincial Health Service Ethical Review Board approved the research protocol. Participants 18 years and older signed a consent form. Participants younger than 18 years signed an assent form and their parent/guardian signed a consent form. All research staff were trained in ethical research and obtaining consent.

Instrument Development and Modification

Focus groups and individual interviews were conducted within the six study communes to help culturally adapt survey scales and items. Survey materials were translated and back-translated. Two qualitative focus group pilots (10 males and 10 females) were conducted to review survey content and wording, and item clarity. Two test–retest quantitative pilots were conducted with 117 youth (52 males, 65 females) for scale reliability (internal consistency).

Measures

The final survey included 215 items and 21 scales. Items and scales reported in this paper include Demographic Characteristics, Relationships and Sexual Intimacy, Alcohol Consumption, the Timeline Followback Method (Sobell & Sobell, 1992; Sobell & Sobell, 1995), and Episode Specific Alcohol Consumption and Engagement in Sexual Behaviors (see Table 1). Using the timeline followback method, respondents’ blood alcohol content (BAC) was calculated for each reported drinking episode, using the formula ([number of drinks/2] × [gender constant/weight in lbs]) − (hours since first drink × 0.016). The gender constant is 7.5 for males and 9.0 for females (Hustad & Carey, 2005). Weight was self-reported.

Table 1.

Overview and Description of Reported Survey Measures

| Demographic characteristics |

|

|

| Relationships and sexual intimacy |

|

|

| Alcohol consumption. |

|

|

| Timeline followback method | The TLFB is a self-report method to assess an individual’s recent daily drinking behavior. Respondents were asked to recall the number of standardized alcoholic drinks and the number of hours in which they consumed the drinks, over the 30 days prior to the survey interview. A calendar was provided with important dates and holidays indicated as well as information and photographs illustrating a standard drink or unit of alcohol based on locally available and popular alcoholic beverages. | |

| Episode specific drinking and sexual behavior |

|

|

Research Population and Sampling

Census data for the six study communes was obtained from the Khanh Hoa Provincial Health Services. There were 14,554 youth within the study age range (16 to 24 years). Stratifying by commune and gender, 1,693 youth (846 males, 847 females) were randomly selected to participate in the survey. Community recruiters contacted the youth to introduce the program and schedule a time for interested youth to meet with the project data collectors for consent/assent procedures and to complete the survey. A total of 951 youth (56%) were successfully contacted and 93% (880/951) of those youth completed the survey. Youth not contacted included those who had moved to study or work outside of Nha Trang. Those who did not participate included youth already married, outside of the age limitations because of misinformation on the census or refusal to participate.

Survey Data Collection

Survey data were collected over a 2-month period in the summer of 2005 at commune health centers. Surveys were conducted in a private space on an individual basis with a same-gendered trained data collector. Data collectors read each item and response options out loud to the respondents. Respondents marked their answer on a separate copy of the survey. Youth unable to read or follow the survey were provided the opportunity to verbally respond to the survey. Only 2.8% (25/880) of respondents were observed to have very low literacy. Surveys took an average of 93 minutes to complete. Respondents were provided a stipend (~US$3.00) for their participation.

Survey Data Analysis

Main outcome variables are a three-category sexual behavior variable (no intimacy, touchonly, anysex), and alcohol drinking status classified as “abstainers” (never drank alcohol), “former drinkers” (drank 6 month ago or more), and “current drinkers” (drank within the past 6 months). Continuous alcohol-related variables include frequency of drinking in the past 30 days, quantity drank each episode and calculated BACs for peak and average drinking occasion.

Descriptive analysis was performed using proportions for categorical variables and means for continuous variables by gender. Chi-square test was used to compare proportions among groups, and t test or ANOVA was used to compare means among groups.

Continuous drinking variables were also categorized for male and female respondents taking into account significantly higher levels of drinking among male respondents (see Table 2). Generalized logit model (when the proportional odds assumption does not hold) was used to study the association between three-level sexual behavior variable (no intimacy, touchonly, and anysex behavior) and the alcohol drinking status for males and females, controlling for age and other demographic variables that are significantly associated with sexual behavior. The generalized logit model allows the possibility that the odds ratio of anysex is different from the odds ratio of touchonly (using no intimacy as the reference category). Odds ratios and their confidence intervals are reported.

Table 2.

Categorization of Days Drinking and Number Drinks, Peak Number Drinks and Peak and Mean BACs in Past 30 Days by Gender

| Male | Female | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of days drinking past 30 days | No drinking | No drinking |

| 1 to 2 days drinking | 1 day drinking | |

| ≥3 days drinking | ≥2 days drinking | |

| Number of drinks in past 30 days | No drinks | No drinks |

| 1 to 10 drinks | 1 drink | |

| ≥11 drinks | ≥2 drinks | |

| Peak number of drinks per episode in past 30 days | No drinks | No drinks |

| 1 to 4 drinks | 1 drink | |

| ≥5 drinks | ≥2 drinks | |

| Peak level of BAC in past 30 days | <0.109 | <0.0106 |

| >0.109 | <0.0106 | |

| Mean BAC in past 30 days | <0.081 | <0.0089 |

| >0.081 | >0.0089 |

Logistic regression analyses were performed to assess the associations among binary sexual risk behaviors (using condoms more than half of the time, at least two sexual partners), drinking before sexual intercourse, and detailed drinking variables for those who ever drank, for males and females separately. In the first model, independent variables considered include days of drinking in the last month, number of alcohol drinks consumed in the last month, and the peak number of alcohol drinks per episode. In the second model, independent variables considered include the peak level of BAC and the average BAC level over last month. Stepwise variable selection method is used to decide which variables to be kept in each model. Odds ratios and their confidence intervals are reported (Hosmer & Lemeshow, 1989).

Results

General demographics

The survey included 53.2% (468/880) female respondents. The mean ages for male and female respondents were 20.2 (SD = 2.6) and 20.0 (SD = 2.6) years, respectively (t = −0.973, 878 df, p = .331). A total of 43.7% (180/412) males and 48.3% (228/468) females were currently in school (χ2 = 1.87, 1 df, p = .172). Among respondents not in school, males (102/232: 44.0%) were less likely to have completed high school than females (130/242: 53.7%; χ2 = 4.51, 1 df, p = .034).

More males (209/412: 50.7%) were employed than females (188/467: 40.3%; χ2 = 9.70, 1 df, p = .002). The monthly income for male respondents was 860,000 VND (~US$54) compared to 600,000 VND (~US$38) for females (t = −6.76, 393 df, p < .0001).

Gender and socializing

Female respondents spent less time with friends and had older friends. On a monthly basis, females reported spending a mean of 202,000 VND (~US$13) on personal expenses compared to 302,000 VND (~US$19) for males (t = −7.09, 819 df, p = .000). There are a variety of places which serve alcohol. These range from small pavement “drinking houses” which serve bottled beer and/or “bia toui/hoi” (fresh/draft beer) by the liter to more recently built “ca phe bars.” Alcohol is also commonly served at karaoke, billiard halls, and in cafes. Males reported visiting these establishments more frequently than female respondents with 73.0% (300/411) of males respondents visiting a café, 36.8% (151/410) visiting a billiard hall, and 34.1% (140/410), visiting a drinking house in the past month. Approximately one quarter of both males and females had gone to karaoke.

Relationships and Sexual Intimacy

A total of 53.9% (222/412) male respondents reported ever having a girl-friend and 54.4% (254/467) female respondents reported ever having a boyfriend. Rates of sexual intimacy (“touchonly” and “anysex”) were relatively low, although engagement in these behaviors was significantly more likely among older male respondents. Thus, 20.6% (85/412) males and 13.7% (64/468) females reported sexual touching (touchonly), while 16.0% (66/412) males and 4.9% (23/468) females reported vaginal, anal, and/or oral sex (anysex; χ2 = 42.78, 2 df, p < .0001). Overall, 9.5% (84/870) respondents reported vaginal sex, with 14.3% (12/84) of these respondents separately reporting anal and/or oral sex. No respondents reported exclusively engaging in anal sex and only 0.6% (5/870) reported engaging only in oral sex.

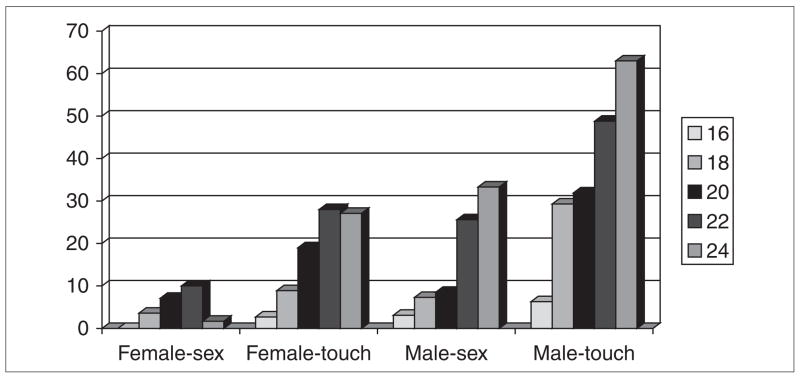

Male respondents reporting anysex had a mean age of 21.9 years compared to 21.6 years for those reporting touchonly and 19.3 years for males with no sexual intimacy (neither touchonly nor anysex; F = 50.13, df 2,405, p < .0001). The average age of female respondents reporting no sexual intimacy was 19.7 years, with those reporting touchonly and anysex at 21.5 and 20.6 years, respectively (F = 13.49, df 2,461, p < .0001). There is a rapid increase in male respondents reporting anysex after age 20, with rates between 25% and 34% for all years between 21 and 24 compared to less than 9% for male respondents 20 years and younger. Females did not show this same trend (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Engagement in sexual touching (touch) and vaginal, oral, anal sex (sex) by age and gender

Gender and Alcohol Consumption

A total of 78.2% (322/412) males and 55.1% (258/468) females reported “ever drinking alcohol” (χ2 = 51.71, 1 df, p = .000). Mean age of first drink for males was 17.7 years (SD = 2.83) and for females 18.0 years (SD = 3.63; t = −0.826, 386 df, p = .409). Among those reporting “ever drink”, 84.5% (272/322) male respondents compared to 61.1% (157/256) females reported drinking in the past 6 months (χ2 = 40.71, df 1, p < .0001), and 22.6% (72/319) males compared to 4.7% (12/258) females reported being drunk in the past 6 months (χ2 = 36.82, df 1, p < .0001). Among those reporting alcohol consumption in the past 30 days, the average number of standard drinks per week for males was 3.13 (SD = 3.9; range = 0.23 to 24.5) and for females, 0.51 (SD = 0.9; range = 0.12 to 6.5; t = 6.57, 324 df, p = .000).

Alcohol Consumption Behaviors and Sexual Intimacy

Both male and female respondents who had at least one alcoholic drink in the past 6 months were more likely than those who never drank (abstainers) to have engaged in some form of sexual intimacy (touchonly or anysex; Table 3). Demographic factors related to engagement in sexual intimate behaviors were controlled. For male respondents these indices included age, school status, ever watched satellite television, and contact with tourists or other foreigners and for female respondents the significant indices were age and relative age of friends to respondent. After controlling for these factors, a significant relationship was still evident comparing recent drinkers and abstainers and engagement in sexual intimate behaviors for both males (OR = 4.59, CI [95%] = 2.0, 10.54: p < .0013) and females(OR = 2.81, CI [95%] = 1.59, 4.95: p < .0014).

Table 3.

Alcohol Consumption and Sexual Behaviors (“Touchonly” and “Anysex”) by Gender

| Abstainersa | Past alcohol consumptionb | Recent alcohol consumptionc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | No intimacy | 49.34% | 21.75% | 28.91% | χ2 = 19.83, 4 df, p < .0015 |

| 186/377 | 82/377 | 109/377 | |||

| Touchonly | 28.56% | 20.63% | 50.79% | ||

| 18/63 | 13/63 | 32/63 | |||

| Anysex | 21.74% | 21.74% | 56.52% | ||

| 5/23 | 5/23 | 13/23 | |||

| Male | No intimacy | 32.17% | 14.73% | 53.10% | χ2 = 53.43, 4 df, p < .0001 |

| 83/258 | 38/258 | 137/258 | |||

| Touchonly | 3.57% | 9.52% | 86.90% | ||

| 3/84 | 8/84 | 73/84 | |||

| Anysex | 6.06% | 6.06% | 87.88% | ||

| 4/66 | 4/66 | 58/66 |

Abstainers: Never consumed alcohol.

Past alcohol consumption: Last drank more than 6 months ago.

Recent alcohol consumption: Drank within the past 6 months.

Using ANOVA, relationships were assessed between drinking behaviors (frequency of drinking and peak standard drinks for one episode), consequences of drinking (Mean and peak BAC in the past month) and sexual behaviors (touchonly and anysex). Males reporting touchonly and anysex also report more days drinking in the past month, more drinks for one peak episode of drinking, a higher mean BAC, and a higher peak BAC. Female respondents reporting touchonly and anysex also report more drinks per peak episode of drinking in the past month and show a higher mean BAC and a higher peak BAC than females reporting no intimacy. For each of these significant trends, there is a progressive increase in alcohol consumption from the no intimacy group to the touchonly group to the anysex group (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Alcohol Consumption by Quantity and BAC by Sexual Behaviors by Gender

| Frequency of drinking: Number of days drink in past month |

Peak standard drinks for one drinking episode in past month |

BAC in past month |

Peak BAC in past month |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual behaviors | M (SE) | M (SE) | M (SE) | M (SE) |

| Males | ||||

| No intimacy | 2.50 (0.35) | 3.78 (0.34) | 0.066 (0.007) | 0.082 (0.008) |

| Touch only | 3.65 (0.43) | 4.71 (0.43) | 0.081 (0.009) | 0.109 (0.011) |

| Any sex | 4.94 (0.49) | 6.63 (0.48) | 0.109 (0.010) | 0.151 (0.012) |

| F = 8.46, 2/216 df** | F = 11.67, 2/216 df** | F = 6.97, 2/216 df** | F = 10.84, 2/216 df** | |

| Females | ||||

| No intimacy | 1.33 (0.10) | 1.19 (0.15) | 0.024 (0.005) | 0.027 (0.006) |

| Touch only | 1.52 (0.16) | 1.41 (0.24) | 0.031 (0.008) | 0.036 (0.009) |

| Any sex | 1.20 (0.25) | 2.30(0.36) | 0.065 (0.012) | 0.072 (0.014) |

| F = 0.75, 2/88 df | F = 4.09, 2/88 df* | F = 5.48, 2/88 df* | F = 4.37, 2/88 df* | |

Note: BAC = blood alcohol content.

p < .05.

p < .01.

To develop a generalized logit model for sexual behaviors and drinking patterns, the continuous variables for frequency drink (days drink in 30 days), peak quantity of drink at one episode in past 30 days, and average quantity drink in past 30 days were developed for males and for females. For both males and females, all three variables were associated with sexual intimacy; however, among male respondents peak number of drinks at one episode had the strongest association for both sexual intimacy variables (touchonly and anysex). These data indicate a transition of increasing likelihood of engaging in touchonly and anysex with increasing peak number of drinks in one episode. Males who have a peak of 5 or more drinks have an increased odds of engaging in anysex compared to those peaking at 1 to 4 drinks in an episode (OR = 5.21, CI [95%] = 2.47 to 11.01; p < .05) and even greater odds compared to those not drinking (OR = 6.72, CI [95%] = 3.08 to 14.66; p < .05).

Quantity of peak alcohol consumed among female respondents was much less than for males. Nonetheless, at a threshold of 2 or more drinks consumed during a single episode compared to no drinking, we see an increased odds of 5.08 (CI [95%] = 1.96 to 13.16; p < .05) for touchonly, and an odds ratio of 6.21 (CI [95%] = 1.79 to 21.50; p < .05) for anysex (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Odds Ratios With 95% Confidence Limits for Engaging in Touchonly and Anysex by Peak Quantity of Drinks in one Episode in Past 30 Days (By Gender)

| Touchonly | Anysex | |

|---|---|---|

| Males | ||

| Peak of 1 to 4 drinks vs. No drinking | OR = 2.80 | OR = 1.29 |

| CI [95%] = 1.43, 5.45** | CI [95%] = 0.54, 3.08 | |

| Peak of 5 or more drinks vs. Peak of 1 to 4 drinks | OR = 1.04 | OR = 5.21 |

| CI [95%] = 0.55, 1.99 | CI [95%] = 2.47,11.01** | |

| Peak of 5 or more drinks vs. No drinking | OR = 2.92 | OR = 6.72 |

| CI [95%] = 1.38, 6.16** | CI [95%] = 3.08,14.66** | |

| Females | ||

| Peak of 1 drink vs. No drinking | OR = 2.19 | OR = 1.79 |

| CI [95%] = 0.91, 5.32 | CI [95%] = 0.45, 7.06 | |

| Peak of 2 or more drinks vs. Peak of 1 drink | OR = 2.32 | OR = 3.47 |

| CI [95%] = 0.75, 7.19 | CI [95%] = 0.71, 17.00 | |

| Peak of 2 or more drinks vs. No drinking | OR = 5.08 | OR = 6.21 |

| CI [95%] = 1.96,13.16** | CI [95%] = 1.79, 21.50** | |

p < .05.

To assess whether alcohol consumption and sexual behaviors occur sequentially, “event specific” items were included on the survey. Combining these three items (partner drank, respondent drank, both partner and respondent drank), we find that 50.0% (33/66) sexually active males and 30.4% (7/23) sexually active females report at least one incidence of drinking before engaging in sexual intercourse (χ2 = 2.64, df 1, p = .104). When analyzed separately, we find that males are significantly more likely than female respondents to consume alcohol without their partner also drinking (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Specific Events of Alcohol Consumption and Sexual Behaviors by Gender

| Male | Female | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| After your partner drank alcohol, but you did not, have you ever had sex (vaginal, anal, or oral)? | 10.6% (7/66) | 21.7% (5/23) | χ2 = 1.81, df 1, p = .178 |

| After you drank alcohol, but your partner did not, have you ever had sex (vaginal, anal, or oral)? | 47.0% (31/66) | 4.4% (1/23) | χ2 = 13.46, df 1, p < .001 |

| After both you and your partner drank alcohol, have you ever had sex (vaginal, anal, or oral)? | 28.8% (19/66) | 13.0% (3/23) | χ2 = 2.27, df 1, p = .132 |

Among male ever drinkers, those reporting a peak of 5 or more drinks compared to those reporting a peak of 1 to 4 drinks have higher odds of reporting drinking before engaging in sexual intercourse (OR = 3.46, CI [95%] = 1.36, 8.82, p < .05). We also find that among male ever drinkers, those reporting 11 or more drinks compared to those respondents reporting 1 to 10 drinks within the last 30 days have higher odds of reporting drinking before engaging in sexual intercourse (OR = 10.27, CI [95%] = 3.72, 28.32, p < .0001).

Alcohol Consumption and Sexual Risk Behaviors

Items analyzed for higher sexual risk behaviors included frequency of past condom use and number of lifetime sexual partners. Across sexually active respondents, condom use is low and inconsistent with 52.5% (32/61) male and 66.7% (10/15) female respondents using condoms “half the time or less“ (χ2 = 0.983, 1 df, p = .3215). However, for both males and females there were no relationships between frequency of past condom use and quantities of alcohol consumed in past 30 days (number days drank, peak number drinks, number of drinks in past 30 days, peak or mean BACs).

Males reported a mean of 1.80 partners (SD = 1.04, range = 1 to 5) and females reported a mean of 1.05 partners (SD = 0.21, range = 1 to 2; t = −3.347, 84 df, p = .001). Only one female respondent reported having two lifetime sexual partners. Male respondents who reported they and/or their partner drank prior to engaging in sexual behaviors (event-specific drinking) had a mean of 2.1 (SD = 1.21) sexual partners compared to 1.5 (SD = 0.73) for males not reporting concurrent drinking and sexual behaviors (t = −2.319, df 1, p = .024). Males who reported having at least 11 drinks in the past 30 days had higher odds of reporting 2 or more sexual partners compared to those who reported 1 to 10 drinks in the same time period (OR = 4.72, CI [95%] = 1.33, 16.78, p = .0369). There were no significant differences in frequency of condom use in relationship to number of lifetime sexual partners (χ2 = 7.859, df 8, p = .447) (Table 7).

Table 7.

Frequency of Condom use by Number of Lifetime Partners for Sexually Active Male Respondents

| One partner | Two partners | Three or more partners | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never use condoms | 32.1% (17/53) | 35.3% (6/17) | 21.4% (3/14) | 31.0% (26/84) |

| Rarely use condoms | 15.1% (8/53) | 23.5% (4/17) | 28.6% (4/14) | 19.0% (16/84) |

| Half the time use condoms | 5.7% (3/53) | 11.8% (2/17) | 7.1% (1/14) | 7.1% (11/84) |

| More than half the time use condoms | 11.3% (6/53) | 5.9% (1/17) | 28.6% (4/14) | 13.1% (11/84) |

| Always use condoms | 35.8% (19.53) | 23.5% (4/17) | 14.3% (2/14) | 29.8% (25/84) |

Discussion

The reported data show the complexity of issues related to engagement in sexual behaviors and alcohol consumption. Not surprisingly, males spend more time socializing with friends and are more involved in “public” activities including time spent at establishments that serve alcohol. This finding is consistent with expectations regarding female responsibilities for family and home, leaving less time for young women to spend with peers. Male respondents were more likely to be employed, make more money, and have more personal spending money.

Young men are more likely to be exposed to outside influences including peer and colleague expectations and pressures regarding alcohol consumption. Toasting and drinking “games” (e.g., “uống trăm phần trăm” [drink 100%]) which are frequently a part of social gatherings increase the amounts of alcohol consumed during a single episode (Tho et al., 2007). At many restaurants and cafes, alcohol companies employ young women to promote a particular product. When beer is ordered, a crate of beer is brought to the table, and as each bottle is emptied a new bottle is opened by the promoter. These contexts of who is drinking together, the rules and social expectations for drinking, as well as the economics of the alcohol business in Viet Nam are essential to understanding quantities of alcohol consumed and potential links to risk behaviors.

In addition, with the increase in product advertisements and the availability of the Internet and satellite television, youth are regularly exposed through these media to images about drinking and alcohol consumption and sexuality. These messages often reinforce cultural expectations for men to drink alcohol as a part of social gatherings as well as the role of alcohol in “romantic” and/or sexual relationships.

For male respondents reporting both alcohol consumption and “anysex,” quantities of alcohol consumed and resulting calculated BACs are great enough to suggest that many of these young men may be engaging in sex when they are intoxicated to a level which could significantly alter their judgment. With 47% of sexually active males reporting at least one “specific episode” of engaging in sexual behaviors after consuming alcohol, we need to further explore the concurrency of these behaviors among young Vietnamese men. Further exploration of alcohol myopia theory within the Vietnamese adolescent and young adult male contexts of drinking is one potential avenue for increasing our knowledge of intoxication, impairment of cognitive functioning, and engagement in sexual behaviors.

Among the various changes in gender roles is more young Vietnamese women reporting alcohol consumption than in the past (Kaljee et al., 2005). While the female respondent data also indicate a relationship between alcohol consumption and sexual experience, what are different for the female respondents are the relatively small quantities of alcohol consumed. Even among female respondents reporting engagement in anysex, their estimated peak BACs are below 0.08. While this would cause some physical effects in terms of cognitive functioning, these low levels of blood alcohol suggests the need for further exploration of alcohol expectancy effect as well as other psychosocial factors in relationship to women’s alcohol consumption and engagement in sexual behaviors. These data are suggestive of other research conducted in the United Kingdom, whereby alcohol was used as an “excuse” for engaging in sexual behaviors (Coleman, 2005). As previously noted, the strong social taboo against young women engaging in premarital sex may very well exacerbate this relationship between alcohol consumption and sexual behaviors. Another avenue for further exploration is the potential influence of men’s alcohol consumption and women’s sexual risk-taking behaviors (Kalichman, Simbayi, Kaufman, Cain, & Jooste, 2007).

While our data do not show a significant relationship between alcohol consumption and frequency of condom use, the overall low percentage of youth reporting consistent condom use increases risks for all sexually active adolescents and young adults. Current literature provides a “mixed picture” of the relationship between condom use and alcohol consumption. In a review of literature published between 1993 and 2007, alcohol use is negatively associated with condom use (Sarkar, 2008). However, in a U.S.-based study designed to assess accuracy of recollection of condom use, data suggest that individuals consuming alcohol prior to a sexual encounter tend to overestimate noncondom use in these encounters (Leigh, Morrison, Hoppe, Beadnell, & Gillmore, 2008). An important link however may be more evident between alcohol use and the combined higher risk behaviors of multiple partners, casual partners, and inconsistent condom use. In a study of U.S. college students, noncondom use and alcohol consumption was associated with casual partners but not regular partners (Brown & Vanable, 2007). In Uganda, in-school adolescents ever reporting being drunk and having two or more partners were less likely to use condoms (Twa-Twa, Oketcho, Siziva, & Muula, 2008). Moreover, in Peru, among adolescent and young adult men, heavy drinking was associated with having multiple partners, and when controlling for amounts of alcohol consumed, alcohol expectations were related to noncondom use including casual partners (Galvez-Buccollini et al., 2008).

In our work, the relationship between multiple partners and male consumption of alcohol is a particular concern. Establishments in Viet Nam such as karaoke om and bia om (karaoke & hugs; beer & hugs) where large quantities of alcohol consumed with immediate access to commercial sex workers increase risks for STIs including HIV/AIDS. Among sexually active young men, casual sex and visiting sex workers is fairly common (Duong et al., 2008; UNAIDS, 2006) Recent HIV/AIDS research shows increasing use of injection drugs by female commercial sex workers (Detels, 2004) and high rates of unprotected sex between male IDUs and commercial sex workers (Go et al., 2006) resulting in increased risks for HIV among clients of sex workers. Young men engaging in transactional sex as clients increase the potential for a generalized HIV/AIDS epidemic and increasing rates of other STIs. These are recognized as significant issues for Viet Nam (Ministry of Health Viet Nam, n.d.). While multiple partners are not necessarily indicative of transactional sex, engagement in sexual relationships with multiple partners combined with low condom use constitutes a risk for HIV/AIDS, other STIs, and unwanted pregnancies for adolescents and young adults. Young women may be unaware of their partner’s sexual history and feel at low risk for HIV and other STIs because of their monogamous relationship with a steady boyfriend or husband.

There are some limitations with the current study. The data have relatively low reported rates of engagement in sexual behaviors, particularly among female respondents. While a number of methodological procedures were enacted in other to increase the participants’ feeling of confidentiality, it should be acknowledged that social stigma associated with sexual behaviors for unmarried youth can decrease likelihood of revealing this information. These data are also collected within a small geographic area, and variations across regions can be expected. In addition, these are cross-sectional data which limit causal analyses. Longitudinal qualitative and quantitative data on drinking and sexual risk behaviors among Vietnamese youth are necessary to further knowledge regarding the development of drinking patterns, associated sexual risks behaviors, and potential mediating factors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank staff at the Khanh Hoa Provincial Health Services and the community recruiters and youth participating in their survey in Vșnh Hải, Vșnh Hiệp, Vșnh Phước, Vșnh Thạnh, Vșnh Thọ, and Phước Long.

Funding

This project was funded through the United States National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R21AA014774).

Biographies

Linda M. Kaljee, PhD, is associate professor at the Pediatric Prevention Research Center, Wayne State University. She is trained in anthropology and has worked in adolescent reproductive health and HIV/AIDS prevention for the past 18 years. Her work has included HIV/AIDS prevention program development and evaluation in the United States, China, the Bahamas, and India. She has worked in Viet Nam since 1997.

Mackenzie S. Green, MHS, is a research associate in Health Services Research at Family Health International, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina. At the time of writing, she was employed by the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Baltimore.

Min Zhan, PhD, is assistant professor at the Department of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, University of Maryland Baltimore School of Medicine. Dr. Zhan is trained in statistics.

Rosemary Riel, MAA, is currently coordinator at the Office of Global Health and the PAHO/WHO Coordinating Center for Mental Health Nursing at the University of Maryland, School of Nursing. She is an applied anthropologist with 10 years of experience in project management, community-based planning and programming, and applied research, including collaborations with university-based initiatives and the international nonprofit sector. Her expertise in global health focuses on gender issues, adolescent reproductive health, HIV/AIDS education, vaccine acceptability and delivery campaigns, and infectious disease in Asia.

Porntip Lerdboon, MPH, currently works at the International Rescue Committee in the Baltimore Resettlement Center as the public health advocate. She graduated from Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine with a master’s of public health (international health and development). She has worked abroad in a refugee camp along the Thailand–Myanmar (Burma) border as the community health education coordinator and in Vietnam developing gender-specific HIV prevention curricula for Vietnamese adolescents. She has also worked with migrant and seasonal farm workers in New York’s Hudson Valley and on the Eastern Shore of Virginia.

Ty W. Lostutter, PhD, received his doctoral degree in clinical psychology at the University of Washington. His clinical and research interests include the prevention and treatment of substance use disorders and comorbid mental health disorders using brief motivational interventions. He is also interested in the use of adapting technology to increase access to efficacious prevention and treatment interventions.

Le Huu Tho, MD, PhD, is Head of the Health Planning Division and the Manager of the Cooperative Public Health Research Office at Khanh Hoa Provincial Health Services, Nha Trang Viet Nam. Dr. Tho has over ten years experience working in HIV research, and he was the project director for the current NIAAA funded project.

Vo Van Luong, MD, MPH, is a specialist in infectious disease and currently is the director of the Nha Trang City Health Services. He previously served as chief for HIV/AIDS treatment at the Khanh Hoa Provincial AIDS Committee.

Truong Tan Minh, MD, PhD, is director of the Khanh Hoa Provincial Health Services. He was a coinvestigator on for the NIAAA alcohol and HIV prevention project, and he has collaborated with several international organizations in HIV/AIDS research and program development.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interests with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

Reprints and permission: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

References

- Alan Guttmacher Institute. Sharing Responsibility: Women, Society, and Abortion. New York: Author; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Brown JL, Vanable PA. Alcohol use, partner type, and risky sexual behavior among college students: Findings from an event-level study. Additive Behaviors. 2007;32:2940–2952. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun SS, Sohn AR. Correlates of problem drinking by the alcohol use disorders identification test on Korean college campus [English Abstract] Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health. 2005;38:307–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman LM. Report prepared for the Health Development Agency and the Teenage Pregnancy Unit. Brighton, UK: Trust for the Study of Adolescence; 2005. Young people, “risk,” and sexual behavior: A literature review. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman LM, Cater SM. A qualitative study of the relationship between alcohol consumption and risky sex in adolescents. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2005;34:649–661. doi: 10.1007/s10508-005-7917-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Alcohol use and risky sexual behavior among college students and youth: Evaluating the evidence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;14:101–117. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derman KH, Cooper ML, Agocha VB. Sex-related alcohol expectancies as moderators of the relationship between alcohol use and risky sex in adolescents. Journal of Studies in Alcohol. 1998;59(1):71–77. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desapriya EB, Iwase N, Shimizu S. Adolescents alcohol related traffic accidents and mortality in 1999–2000: Problem and solutions [English Abstract, PMID 12138723] Nihon Arukoru Yakubutsu Igakkai Zasshi. 2002;37:168–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detels R. HIV/AIDS in Asia: Introduction. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2004;16(Suppl A):1–6. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.3.5.1.35526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas M. Constructive drinking: Perspective on drink from anthropology. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Duong CT, Nguyen TH, Hoang TTH, Nguyen VV, Do TM, Pham VH, et al. Sexual risk and bridging behaviors among young people in Hai Phong, Vietnam. AIDS Behavior. 2008;12:643–651. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9265-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EC/UNFPA. Reproductive Health Initiative in Asia. New York: Author; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvez-Buccollini JA, Paz-Soldan V, Herrera P, DeLea S, Gilman RH, Anthony JC. Links between sex-related expectations about alcohol, heavy episodic drinking and sexual risk among young men in a shantytown in Lima, Peru. International Family Planning Perspectives. 2008;34(1):15–20. doi: 10.1363/ifpp.34.015.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gefou-Madianou D. Alcohol commensality, identity transformations and transcendence. In: Gefou-Madianou D, editor. Alcohol, Gender, and Culture. London: Routledge; 1992. pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- George WH, Stoner SA. Understanding acute alcohol effects on sexual behaviors. Annual Review of Sex Research. 2000;11:92–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go VF, Frangakis C, Nam le V, Bergenstrom A, Sripaipan T, Zenilman JM, et al. High HIV sexual risk behaviors and sexually transmitted disease prevalence among injection drug users in Northern Viet Nam: Implications for a generalized HIV epidemic. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2006;42(1):108–115. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000199354.88607.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilette DL, Lyons MA. Sensation seeking, self-esteem, and unprotected sex in college students. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2006;7(5):23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hien NT, Long NT, Huan TQ. HIV/AIDS epidemics in Vietnam: Evolution and responses. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2004;16(Suppl 3A):137–154. doi: 10.1521/aeap.16.3.5.137.35527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer DW, Lemeshow A. Applied logistical regression. New York: John Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hustad JTP, Carey KB. Using calculations to estimate blood alcohol concentrations for naturally occurring drinking episodes: A validity study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:130–138. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Update: Viet Nam: Epidemiological fact sheets on HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted infections. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Viet Nam HIV fact sheet. 2006 Retrieved January 9, 2007, from http://www.unaids.org/en/Regions_Countries/Countries/viet_nam.asp.

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kaufman M, Cain D, Jooste S. Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: Systematic review of empirical findings. Prevention Science. 2007;8:141–151. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaljee LM, Genberg BL, Minh TT, Tho LH, Thoa LTK, Stanton B. Alcohol use and HIV risk behaviors among rural adolescents in Khanh Hoa Province Viet Nam. Health Education Research. 2005;20(1):71–80. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaljee LM, Green M, Riel R, Lerdboon P, Tho LH, Thoa LTK, et al. Sexual stigma, sexual behaviors, and abstinence among Vietnamese adolescents: Implications for risk and protective behaviors for HIV, sexually transmitted infections, and unwanted pregnancy. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2007;18(2):48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaljee LM, Tho LH, Hung LQ, Diep HN. HIV prevention for adolescents and young adults in Viet Nam: Multiple perspectives on community-based research within socio-cultural and political-economic change. In: Stanton B, Galbraith J, Kaljee L, editors. The uncharted path from clinic-based to community-based research. New York: Nova Science; 2008. pp. 57–86. [Google Scholar]

- Kolko G. Viet Nam: Anatomy of a Peace. London: Routledge; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kranker D. Drinking and sex: What do they have in common for Vietnamese youth? Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada: Society for Applied Anthropology; 2006. Mar 30, [Google Scholar]

- Le LC, Blum RW, Magnani R, Hewett PC, Do HM. A pilot of audio-computer assisted self-interview for youth reproductive health research in Viet Nam. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;38:740–747. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh BC, Morrison DM, Hoppe MJ, Beadnell B, Gillmore MR. Retrospective assessment of the association between drinking and condom use. Journal of Studies of Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:773–776. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerdboon P, Pham V, Green M, Riel R, Tho LH, Ha NTV, et al. Strategies for developing gender-specific HIV prevention for adolescents in Viet Nam. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2008;20:384–398. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2008.20.5.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Fang X, Stanton B, Feigelman S, Dong Q. The rate and pattern of alcohol consumption among Chinese adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1996;19:353–361. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(96)00159-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Li X, Yang H, Fang X, Stanton B, Chen X, et al. Alcohol intoxication and sexual risk behaviors among rural-to-urban migrants in China. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;79:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Rohsennow DJ. Cognitive processes in alcohol use: Expectancy and the balanced-placebo design. In: Mello NK, editor. Advances in substance abuse: Behavioral and biological research. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; 1980. pp. 159–199. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health Viet Nam. Survey assessment of Vietnamese youth. Ha Noi, Viet Nam: Author; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health Viet Nam. (n.d.) . General Department of Preventive Medicine and HIV/AIDS Control: HIV/AIDS estimates and projections 2005 to 2010. Ha Noi, Viet Nam: Author; [Google Scholar]

- Room R, Agar M, Beckett J, Bennett LA, Casswell A. Comment on alcohol and ethnography: A case of problem deflation? Current Anthropology. 1984;25:178–184. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar NN. Barriers to condom use. European Journal of Contraceptive and Reproductive Health Care. 2008;13(2):114–122. doi: 10.1080/13625180802011302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline followback: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten RZ, Allen J, editors. Measuring alcohol consumption: Psychosocial and biological methods. New Jersey: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Alcohol consumption measures. In: Allen JP, Columbus M, editors. Assessing alcohol problems: A guide for clinicians and researchers. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 1995. pp. 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K, Osaki Y, Minowa M, Wada K, Ohida T, Doi Y, et al. Japanese national survey of adolescent drinking behavior: Comparison between 1996 and 2000 surveys [English Abstract. PMID 14639921] Nihon Arukoru Yakubutsu Igakkai Zasshi. 2003;38:425–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thato S, Charron-Prochownik D, Dorn LD, Albrecht SA, Stone CA. Predictors of condom use among adolescent Thai vocational students. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2003;35:157–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2003.00157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tho LH, Singhasivanon P, Kaewkungwai J, Kaljee L, Charoenkul C. Sexual behaviors of alcohol drinkers and non-drinkers among adolescents and young adults in Nha Trang, Viet Nam. Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 2007;38:152–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JC, Kao TC, Thomas RJ. The relationship between alcohol use and risk-taking sexual behaviors in a large behavioral study. Preventive Medicine. 2005;41:247–252. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twa-Twa JM, Oketcho S, Siziva S, Muula AS. Prevalence and correlates of condoms use at last sexual intercourse among in-school adolescents in urban areas of Uganda. East African Journal of Public Health. 2008;5(1):22–25. doi: 10.4314/eajph.v5i1.38972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. New five year plan for Vietnam. 2007 Retrieved September 26, 2008, from http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/NEWS/0,,contentMDK:21194622~pagePK:64257043~piPK:437376~theSitePK:4607,00.html.

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Western Pacific. STI/HIV consensus Report on STI, HIV, and AIDS Epidemiology, Viet Nam. Geneva, Switzerland: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Sexual relations among young people in developing countries. 2003 Retrieved June 2, 2008, from www.who.int/reproductive-health/adolescent/publications/RHR_01_8_Sexual_relations.