Abstract

Tremorgenic mycotoxins are a group of indole alkaloids which include the quinazoline-containing tryptoquivaline 2 that are capable of eliciting intermittent or sustained tremors in vertebrate animals. The biosynthesis of this group of bioactive compounds, which are characterized by an acetylated quinazoline ring connected to a 6-5-5 imidazoindolone ring system via a 5-membered spirolactone, has remained uncharacterized. Here, we report the identification of a gene cluster (tqa) from P. aethiopicum that is involved in the biosynthesis of tryptoquialanine 1, which is structurally similar to 2. The pathway has been confirmed to go through an intermediate common to the fumiquinazoline pathway, fumiquinazoline F, which originates from a fungal trimodular nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS). By systematically inactivating every biosynthetic gene in the cluster, followed by isolation and characterization of the intermediates, we were able to establish the biosynthetic sequence of the pathway. An unusual oxidative opening of the pyrazinone ring by an FAD-dependent berberine bridge enzyme-like oxidoreductase has been proposed based on genetic knockout studies. Notably, a 2-aminoisobutyric acid (AIB)-utilizing NRPS module has been identified and reconstituted in vitro, along with two putative enzymes of unknown functions that are involved in the synthesis of the unnatural amino acid by genetic analysis. This work provides new genetic and biochemical insights into the biosynthesis of this group of fungal alkaloids, including the tremorgens related to 2.

Keywords: mycotoxins, alkaloids, aminoisobutyrate, oxidoreductase

INTRODUCTION

Tremorgenic mycotoxins are a group of indole alkaloids that are capable of eliciting intermittent or sustained tremors in vertebrate animals by acting on the central nervous system (CNS).1 Grains, forages and animal feeds contaminated with the tremorgen-producing molds are one of the major sources of mycotoxin intoxications in cattle, sheep and dogs, where the clinical symptoms include diminished activity and immobility, followed by hyperexcitability, muscle tremor, ataxia, titanic seizures and convulsions.1,2 Based on their structural features, the tremorgenic agents can be divided into the indole-diterpenoids (e.g. penitrems and paspalitrems), the prenylated indole-diketopiperazines (e.g. fumitremorgens and verruculogens), and the quinazoline-containing indole alkaloids related to tryptoquivaline 2 (Scheme 1).3,4 Tryptoquialanine 1 is highly similar to 2 and differs only in the alkyl substitution in the quinazoline ring. The mode of action of these tremorgens is not well understood, but they are thought to interfere with neurotransmitter release.5–7 Some of the tremorgens also exhibit useful biological activities, for example, fumitremorgin C is a potent and specific inhibitor of breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP),8 while the penitrems are shown to exhibit potent insecticidal activity.9–11 Biosynthesis of the tremorgenic indole-diterpenoids and prenylated indole-diketopiperazines are currently subjects of intensive studies.12–15 Comparatively, the biosynthesis of the tremorgenic quinazoline alkaloids related to 1 and 2 has not been elucidated.

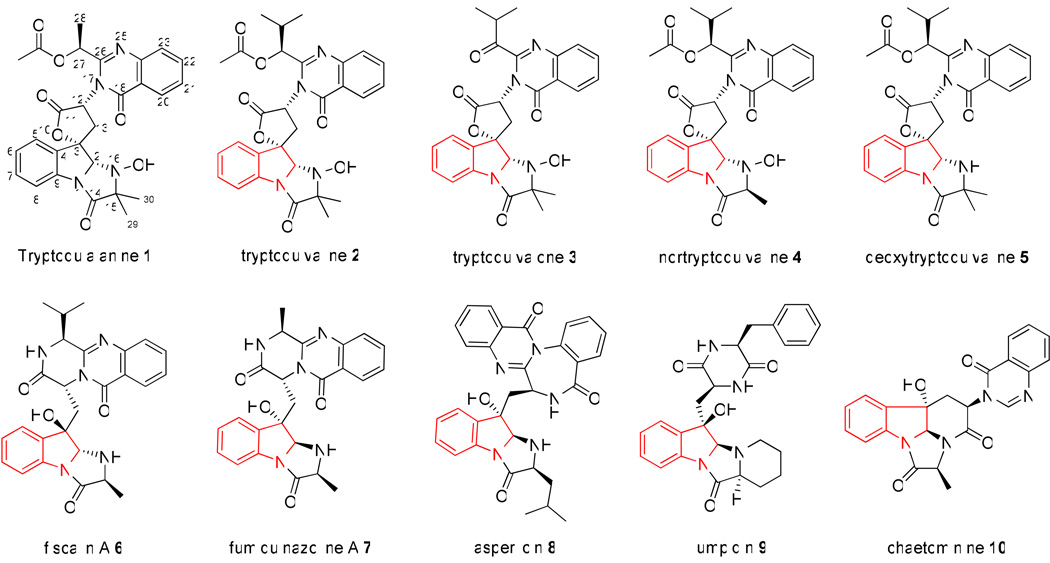

Scheme 1.

Tryptoquialanine 1, tryptoquivaline 2 and related fungal indole alkaloids

The structurally related 1 and 2 are produced by several fungi in the Penicillium spp. and Aspergillus clavatus, respectively.16–18 Both 1 and 2 are multicyclic compounds that exhibit structural features not observed among other indole alkaloids (Scheme 1). Common to both compounds is an acetylated quinazoline ring connected to a 6-5-5 imidazoindolone ring system via a 5-membered spirolactone. The imidazolidone ring is heavily modified, containing the N16 hydroxylamine and the C15 gem-dimethyl group. The structural difference between 1 and 2 is thought to arise from the incorporation of alanine or valine, respectively. The structures of 1 and 2 are also related to the pyrazino[2,1-b]quinazoline alkaloids such as fiscalin A 6 and fumiquinazoline A 7.19,20 These multicyclic scaffolds are assembled from various proteinogenic and nonproteinogenic amino acids by the actions of short nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) assembly lines21,22. Common building blocks shared by many compounds in this family are an anthranilic acid and a tryptophan.16,23

Recently, the anthranilate-activating adenylation (A) domains of several fungal NRPS have been characterized and the modular assimilation of the amino acids to synthesize 7 in Aspergillus fumigatus has been partially reconstituted in vitro.23,24 The formation of the imidazoindolone moiety in 7 has been shown to involve a two-step oxidative-acylation of the indole ring by a single module NRPS and a flavin-dependent monooxygenase. A similar mechanism is likely involved in the biosynthesis of 1 and 2, as well as other imidazoindolone-containing alkaloids, such as 9 and 10.25,26 Nevertheless, it is not known whether a pyrazinoquinazoline intermediate analogous to 7 is involved in the biosynthesis of 1 and 2. Isolation of metabolites related to 2, such as tryptoquivalone 3, nortryptoquivaline 4 and deoxytryptoquivaline 5 have provided hints regarding possible biosynthetic intermediates and the origins of unique structural features.16,27,28 For example, the isolation of 4 suggests that the gem-dimethyl group present in 2 may arise from the α-methylation of a monomethylated intermediate. However, to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the biosynthetic mechanisms of these complex fungal alkaloids, a combination of both genetic and biochemical approaches are needed, starting from the identification of the respective biosynthetic gene clusters.

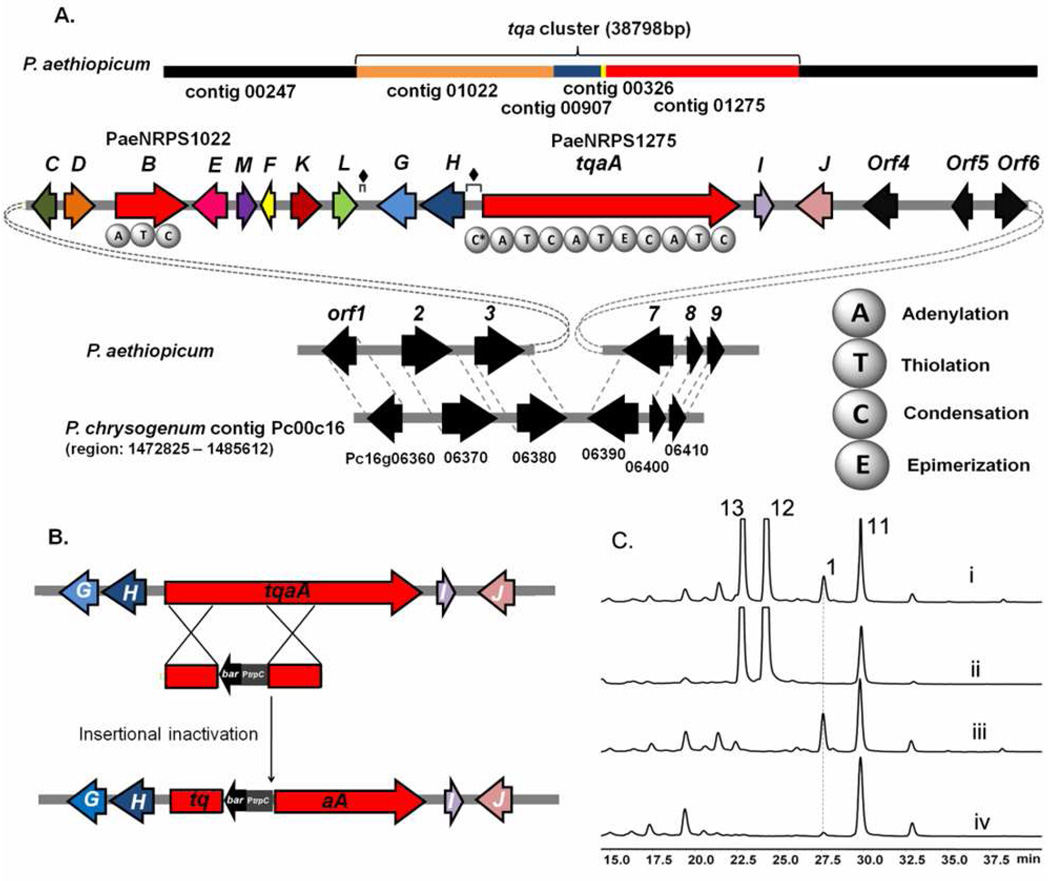

Recently, we used 454 sequencing technology to gain partial genome information of P. aethiopicum and determined the gene clusters involved in biosynthesis of the aromatic polyketides viridicatumtoxin 11 and griseofulvin 12 (Scheme 2).29 P. aethiopicum and P. digitatum have been reported previously to produce 1; and a compound that has identical UV absorbance and mass to 1 were indeed detected by us in the extracts of P. aethiopicum. Therefore, the availability of the genome sequence data presented an excellent opportunity to study the biosynthesis of this family of fungal indole alkaloids. In this report, we present the identification and verification of the tqa gene cluster; functional assignment of the individual genes through genetic and biochemical approaches; and insights into the origins of the unique structural features of 1.

Scheme 2.

Other metabolites produced by P. aethiopicum

RESULTS

Isolation of 1 and Verification of Structure

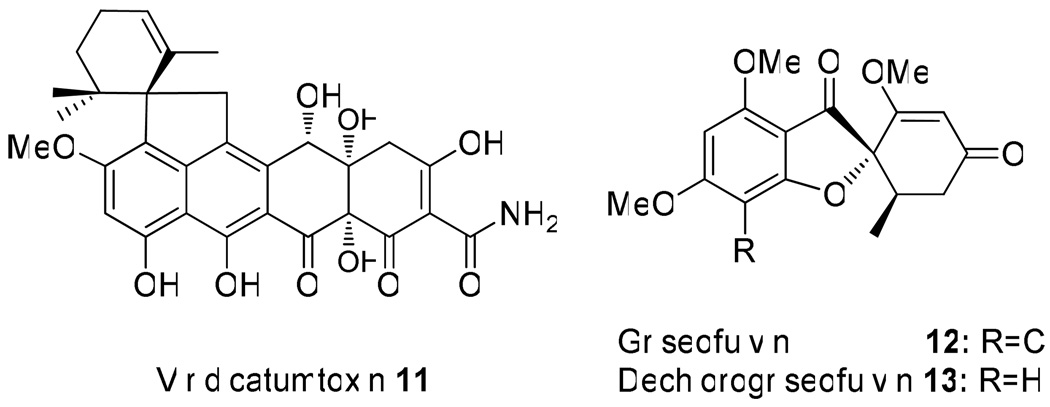

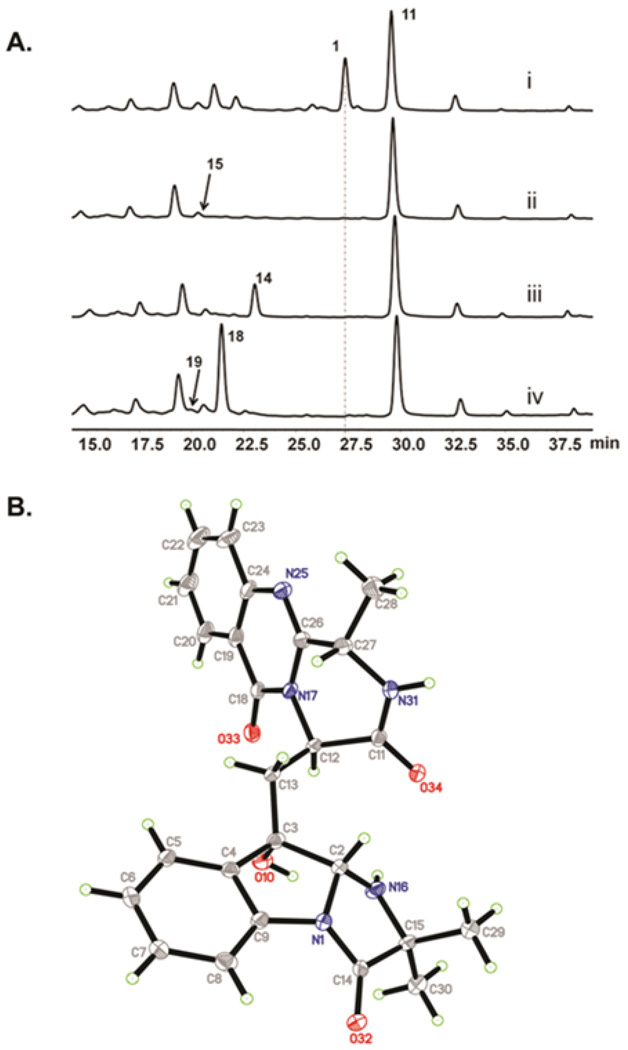

Compound 1 was isolated from a four-day culture of P. aethiopicum grown on YMEG medium at a final titer of 8 mg/L. Proton and carbon NMR spectra of the purified compound matched the previous published data (Table S3, Figure S6).17 To verify the three dimensional structure of 1 as that shown in Scheme 1, especially that of the substituents on the imidazoindolone rings, 1 was crystallized from a methylene chloride/heptane mixture and the X-ray structure was solved as shown in Figure 1. All of the relative configurations of 1 matched that of the solved structures of 2 and 4,16,17,27 including positions C2, C3, C12 and C27. Notably, the syn stereochemical configuration across C2 and C3 of the indole ring is confirmed. The R configuration at position C12 is consistent with incorporation of a d-tryptophan moiety that likely arises through epimerization of l-tryptophan during NRPS assembly. The crystal structure is also consistent with the absolute configurations of 1 determined by NOE and of that of 4 from X-ray crystallography.17,27

Figure 1.

A perspective drawing of 1.

Identification and Verification of Gene Cluster and Analysis

Having verified the structure of 1, we scanned the sequenced genome of P. aethiopicum for possible gene clusters that are responsible for biosynthesis. The NRPS (AnaPS) from Neosartorya fischeri NRRL 181, which synthesizes acetylaszonalenin, has been previously identified.30 Using the adenylation (A) domains of AnaPS, which activates an anthranilate and a tryptophan, the NRPS genes in P. aethiopicum were identified from the local genome database by TBLASTN program (Table S1). By eliminating the common NRPS genes (>89% identity) in P. aethiopicum and P. chrysogenum, the number of candidate NRPS genes was narrowed down from 16 to 10 (Table S1). Further bioinformatic analysis of functional domains along with a specific search of common NRPS homologs present in the genomes of both P. aethiopicum and the 2 producer A. clavatus NRRL1, led to the identification of a candidate trimodule NRPS on contig 1275 (PaeNRPS1275, 67% identity to ACLA017890) and a single module NRPS on contig 1022 (PaeNRPS1022, 64% identity to ACLA017900) (Figure 2A and Table 1). Sequence analysis of PaeNRPS1275 revealed high overall sequence identity (54%), and identical domain arrangement to the recently identified AFUA6G12080 (abbreviated as Af12080), which is proposed to synthesize fumiquinazoline F 14, an intermediate on the way to fumiquinazoline A 7 (Table 1, Figure S7).24 The three A domains of PaeNRPS1275 are predicted to activate anthranillic acid, L-tryptophan, and L-alanine sequentially. The substrate specificity of the first A domain of Af12080, which activates anthranilic acid, has also been confirmed.23 The presence of an epimerization domain (E) following the second module, which is proposed to activate l-tryptophan, is also consistent with the presence of d-tryptophan in the scaffold of 1.

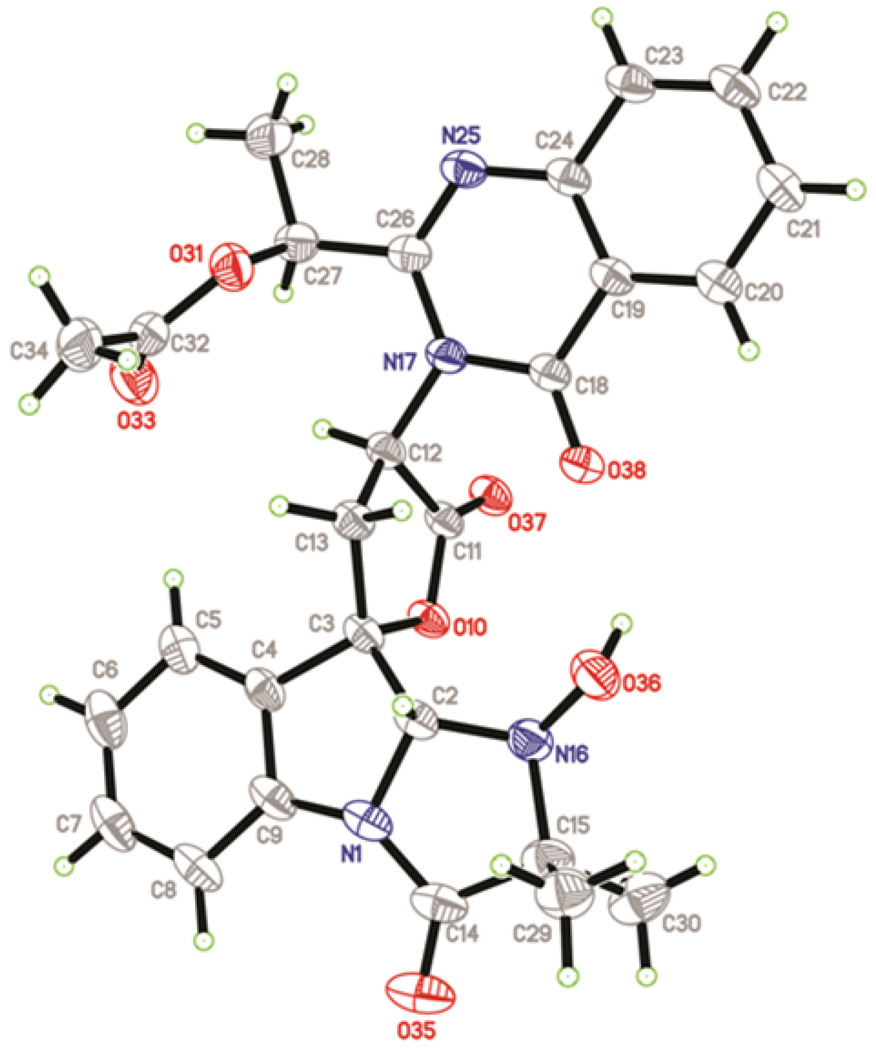

Figure 2.

Organization of the tqa gene cluster and genetic verification of involvement in 1 biosynthesis. (A) The tqa gene cluster; (B) Knockout strategy used to inactivate tqaA; (C)HPLC (280 nm) traces of metabolic extracts from single gene deletion strains of P. aethiopicum. Trace i: wild type strain producing 1, 11–13; trace: ii, ΔtqaA; trace iii, ΔgsfA. This strain was constructed to eliminate the high titer metabolites 12 and 13; and trace iv, ΔgsfA/ΔtqaK. ♦ indicates repeating sequences.

Table 1.

The tqa gene cluster and gene functions assignment

| Gene | Size (bp/aa) |

BLASTP homolog accession number |

Identity/ similarity (%) |

Putative function | E-value | Related metabolite produced after KO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tqaA | 12310/4095 | ACLA_017890 AFUA_6G12080 |

64/77 54/69 |

NRPS (C*ATCATECATC) |

0 0 |

No product |

| tqaB | 3327/1108 | ACLA_017900 AFUA_6G12050 |

67/80 56/72 |

NRPS (ATC) | 0 | 15, 30 |

| tqaC | 1106/363 | ACLA_061530 | 59/72 | Short-chain dehydrogenase |

7e-93 | 25 |

| tqaD | 1542/513 | ACLA_061540 | 50/64 | Acetyltransferase | 2e-113 | 26, 27 |

| tqaE | 1620/466 | ACLA_017910 ADM34142 (notI) ADM34135 (notB) |

61/73 45/63 43/65 |

FAD-dependent oxidoreductase |

8e-173 2e-101 6e-94 |

24, 28 |

| tqaF | 717/238 | AO090701000440 | 70/84 | Haloalkanoic acid dehalogenase |

4e-98 | 1 |

| tqaG | 1723/489 | ACLA_017880 AFUA_6G12070 |

72/83 46/61 |

FAD-dependent oxidoreductase |

0 7e-114 |

18, 19 |

| tqaH | 1545/463 | ACLA_017920 AFUA_6G12060 |

65/82 54/70 |

FAD-dependent oxidoreductase |

1e-177 3e-134 |

14 |

| tqaI | 810/269 | ACLA_017930 | 54/73 | Tryp sin-like serine protease |

2e-68 | 23 |

| tqaJ | 1852/587 | ACLA_098230 | 55/76 | MFS toxin efflux pump |

7e-145 | - |

| tqaK | 1498/416 | UREG_02305 | 33/46 | bZIP DNA-binding protein |

4e-54 | 1 |

| tqaL | 1116/371 | NCU01071 ACLA_063370 |

62/76 60/76 |

Unknown function | 8e-112 | 20 |

| tqaM | 1057/311 | NCU01072 ACLA_063360 |

70/82 50/67 |

Class II aldolase | 2e-124 3e-76 |

20 |

| orf4 | 1302/434 | Pc12g07140 | 96/98 | Unknown function | 0 | 1 |

| orf5 | 819/273 | PMAA_037110 | 49/68 | RTA1-like transmembrane protein |

7e-58 | 1 |

| orf6 | 1387/417 | NECHADRAFT _80860 |

57/75 | Zn2Cys6 transcription factor |

3e-74 | 1 |

To verify the involvement of the PaeNRPS1275 NRPS in 1 biosynthesis, a double recombination cassette was constructed as shown in Figure 2B and transformed into protoplasts of P. aethiopicum. Following selection of glufosinate and PCR verification, seventeen clones were identified to contain a ΔtqaA knockout (Figure S1). None of these clones produced 1 (Figure 2C) while the biosynthesis of other metabolites such as 11–13 were unaffected, confirming the essential role of PaeNRPS1275 (renamed as TqaA) in 1 biosynthesis. To eliminate the production of 12 and 13, which are present at very high levels and can complicate detection and purification of compounds related to 1, we constructed a ΔgsfA mutant of P. aethiopicum using the zeocin selection marker. The ΔgsfA strain was not longer able to synthesize 12 and 13 and is used in subsequent genetic analysis of the tqa cluster.

To complete the tqa gene cluster, a combination of fosmid sequencing and primer walking was performed to link different contigs with contig1275. The putative tqa gene cluster is shown in Figure 2A. To determine the putative boundary of the gene cluster, a comparative analysis with the sequenced P. chrysogenum genome was performed. Interestingly, the upstream orf1-3 and downstream orf7-9 flanking the tqa cluster are highly conserved and syntenic in P. chrysogenum (Table 1 and Figure 2A). We assumed that these conserved syntenic genes do not participate in biosynthesis of 1 but are involved in Penicillium housekeeping roles. Although orf4 is not syntenic, it is highly similar to an ortholog in P. chrysogenum (96% identity, Table 1). The similarity of orf5 and orf6 to the possible orthologs in P. chrysogenum is significantly lower (37% and 25% identity respectively). To exclude the possible involvement of orf4-6 in biosynthesis of 1, single gene deletions were performed for these three genes on ΔgsfA background. As expected, production of 1 was unaffected in the Δorf4, Δorf5 and Δorf6 mutants (Figure S2).

Based on the results from genetic knockouts and comparative genomic analysis, the tqa cluster embedded within the conserved syntenic regions is proposed to span ~32 kB and contains 13 genes (named tqaA – tqaM). The putative assignments of gene functions are shown in Table 1. The gene cluster encodes one transcriptional regulator TqaK. TqaK is a basic-region leucine zipper (bZIP) DNA-binding protein, and shared 27% protein identity with RadR, which regulates radicicol biosynthesis.31 Deletion of tqaK using the bar selection marker did not completely abolish production of 1, as observed for radR, but led to substantial attenuation of 1 titer to less than one-twentieth of the wild type strain (Figure 2C). This confirms the role of TqaK as a positive transcription regulator.

Functions of the two NRPSs in tqa gene cluster

The tqa gene cluster contains a monomodule (A-T-C) NRPS TqaB (PaeNRPS1022), which shares high sequence similarity to Af12050 that acylates l-alanine to the oxidized indole ring of 14 to yield 7. The tqa gene cluster also contains two flavin-dependent oxidoreductases TqaH and TqaG, which are homologous to Af12060 and Af12070 found in the FQA gene cluster in A. fumigatus, respectively (Figure S3). While Af12060 is responsible for oxidation of the indole ring of 14 prior to N-acylation, Afl12070 is likely involved in the oxidative rearrangement of 7 towards other natural fumiquinazolines, such as fumiquinazoline C and D.24 The presence of these enzymes, along with the similarity between TqaA and Af12080, hints that the biosynthesis of 1 may proceed first via the pyrazinoquinazolinone intermediate 14 and then the C2-epimer of 7. Depending on the timing of the introduction of the C15-gem-dimethyl group, either 15-dimethyl-2-epi-fumiquinazoline A 18 or 2-epi-fumiquinazoline A 19 may be a biosynthetic precursor of 1.

To identify these possible intermediates in the tqa pathway, we constructed single-gene knockouts of these three genes based on the ΔgsfA strain and analyzed the subsequent metabolite profiles (Figure 3A). Inactivation of TqaH led to the synthesis of a single metabolite at titers of 6 mg/L. The compound has the mass (m/z = 358) and UV absorption pattern consistent with that of 14. Purification and NMR characterization confirmed the compound is indeed 14 (Table S4), and points to the analogous role of TqaH in oxidizing 14 as previously demonstrated for Af12060 (Scheme 3).24 The ΔgsfA/ ΔtqaB knockout strain no longer produced either 1 or 14, but instead afforded a more polar metabolite with mass (m/z = 374). A possible structure of this compound is 15, which might be the 2, 3-epoxidized version of 14 (Figure S8). This compound is highly unstable during purification and could not be isolated for further spectroscopic analysis. Finally, to probe the pathway shown in Scheme 3 and the role of TqaG as an enzyme that can possibly modify the fumiquinazoline-like intermediate, we analyzed the extract of ΔgsfA/ΔtqaG. This strain produced a predominant compound with mass (m/z = 459) and UV pattern suggestive of fumiquinazolines. This compound was purified and the structure was determined based on extensive NMR data to be that of 18 (Table S5, Figure S9). To verify the syn stereochemical configuration across C2 and C3 of the indole ring, as well the relative stereochemistry of other chiral carbons, the X-ray structure of 18 was determined and shown in Figure 3B.

Figure 3.

Biosynthesis of 18 as an intermediate in the tqa pathway. (A) HPLC analysis (280 nm) of intermediates accumulated in the knockout strains constructed starting from ΔgsfA. Trace i: ΔgsfA; trace ii: ΔgsfA/ΔtqaB; trace iii: ΔgsfA/ΔtqaH; and trace iv: ΔgsfA/ΔtqaG. (B) A perspective drawing of 18.

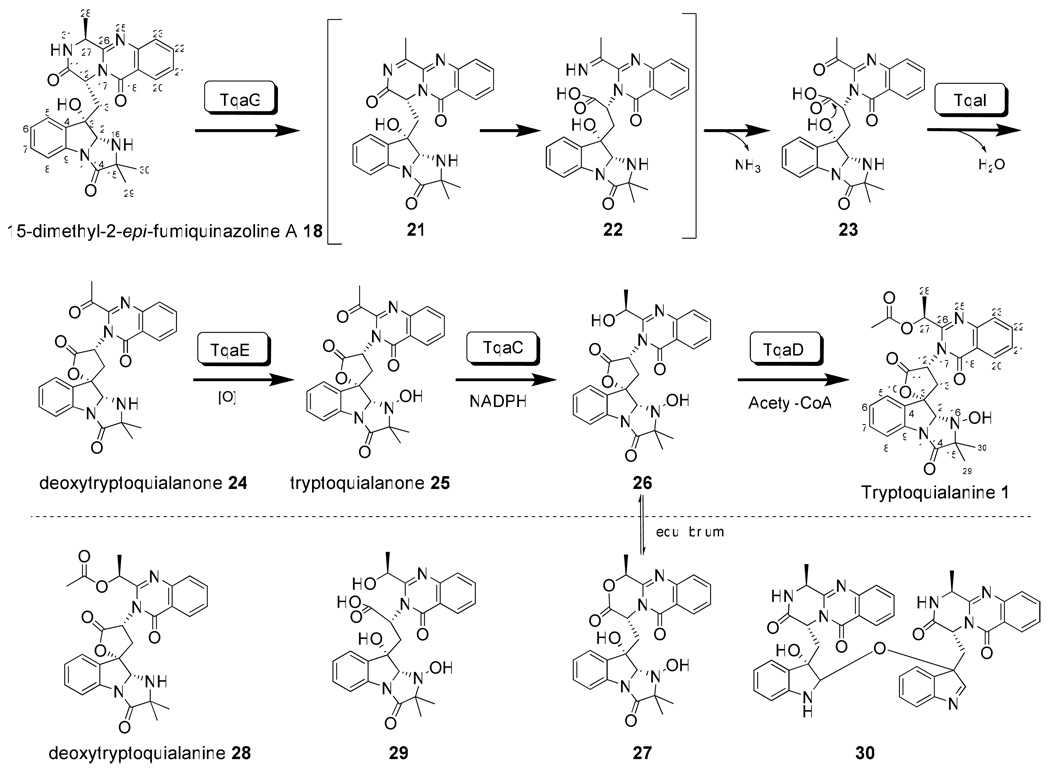

Scheme 3.

Enzymes involved in the synthesis of fumiquinazoline intermediates 14 and 18

More detailed examination of the ΔgsfA/ΔtqaG extract revealed the presence of another quinazoline compound (RT = 19.3 min) with mass (m/z = 445) corresponding to that of 18 with one fewer methyl group. The most likely candidate compound is therefore 19 in which the C15 position is occupied by a single methyl group which can be introduced from the side chain of l-alanine. Although this compound was present in a significantly lower titer, it was purified and thoroughly characterized by NMR to be indeed 19. The loss of 1H signal of the gem-dimethyl at δ=0.93 ppm and 13C signal at δ=23.5 ppm, and the accompanying appearance of additional CH at δ=3.65 ppm and C29 methyl at δ=17.2 ppm, are consistent with the structural difference between 18 and 19 (Table S5, Figure S10).

Origin of gem-dimethyl Quaternary Carbon

The isolation of both 18 and as a minor component, 19, from the ΔgsfA/ ΔtqaG strain provides clues to the timing and source of the gem-dimethyl incorporation. Since 18 is a relatively early intermediate in the pathway that leads to 1, the gem-dimethyl can be introduced via one of the following different routes: a) activation of the nonproteinogenic amino acid 2-aminoisobutyrate (AIB) by TqaB; b) activation of l-alanine by TqaB and α-methylation while attached to the thiolation domain as an activated aminoacyl thioester; or c) direct α-methylation of 19 to yield 18. The last alternative should be a difficult methylation reaction since generation of the nucleophilic enolate at C15 of 19 can be considerably more difficult for the amide carbonyl under biological settings.

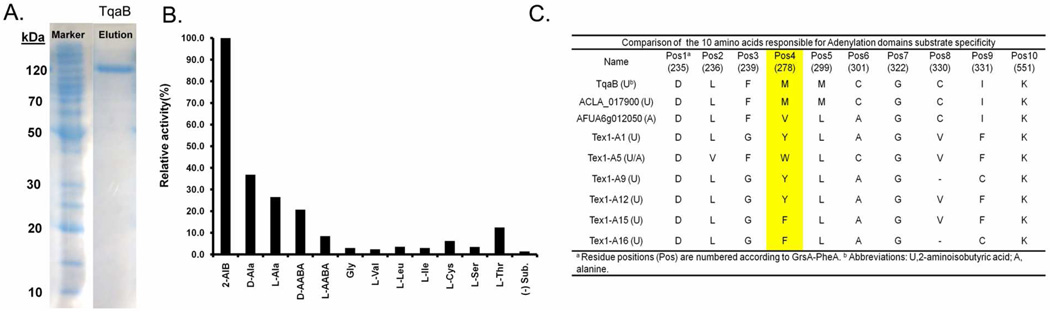

To uncover the origin of the gem-dimethyl group, we first examined the A-domain specificity of TqaB. The uninterrupted tqaB was cloned by using splice-by-overlap extension PCR, expressed from Escherichia coli in both apo- and holo forms, and purified to single-band purity using Ni-NTA affinity chromatography (Figure 4A). ATP-[32P]PPi exchange assay was used to monitor the activity of the A domain in the presence of different amino acids. As shown in Figure 4B, AIB is clearly the preferred substrate for adenylation by the A-domain of apo TqaB; while d-Ala, l-Ala, l-α-aminobutyric acid (AABA), and d-AABA also promoted exchange above background level (37, 27, 21, and 9% the level observed for AIB, respectively). Therefore, it is evident that compared to the functionally analogous Af12050 which does not activate AIB and only weakly activates d-Ala,24 the A domain of TqaB has a clearly different substrate spectrum. The preference towards AIB hence strongly suggests that the gem-dimethyl in 1 and 18 is the result of AIB activation by TqaB.

Figure 4.

Activation of aminoisobutyric acid (AIB) by TqaB. (A) Expression and purification of TqaB from BAP1; (B)ATP-[32P]PPi exchange assay using purified TqaB (100% relative activity corresponds to 55,000 cpm); (C) Alignment of the specificity-determining residues in TqaB with other related AIB (U)/L-alanine (A) activating domains.

To gain insight into the functional difference between the A domains of TqaB and Af12050, we aligned the 10-residue substrate specificity-determining sequence (10AA code) of the A domains, along with known l-Ala specific fungal A-domains (e.g. Af012050) and proposed AIB activating A domains of 2 (ACLA_017900) and that of peptaibol synthetases (Tex1 from Trichoderma virens) (Figure 4C).32 The amino acid sequence of TqaB was submitted to the web-based NRPSpredictor and the 10AA code was extracted as DLFMMCGCIK.33 ACLA_017900 shares the exactly same 10AA code as TqaB, which indicates that ACLA_017900 is likely to activate AIB as well. The 10AA code of Af12050 is highly similar between TqaB and ACLA_017900, but are different at position 3, 4 and 5. On the other hand, the 10AA code of TqaB A domain bears little similarity to AIB-activating domains in Tex1. Additional details with regard to how the 10AA code residues of TqaB and Af12050 may dictate their respective substrate specificities are provided in the discussion.

Having established that AIB is a likely building block of 1, we next investigated the possible tqa enzymes that are involved in the synthesis of AIB. As with many NRPS clusters, the enzymes that are required for the synthesis of nonproteinogenic amino acids used by NRPS are typically encoded in the respective gene clusters.34 These dedicated enzymes are therefore expressed only during the production of the nonribosomal peptides, which minimizes the interference of the products with ribosomal translational machinery. Since no AIB biosynthetic pathway is known to date and because none of the remaining tqa enzymes standout as potential candidates, we decided to generate single gene knockout strains of all remaining genes starting with the ΔgsfA strain. All of the bar-selected clones were verified by PCR to confirm the deletions; and were then cultured and extracted for metabolite analysis. The results of these knockout experiments are shown in Table 1.

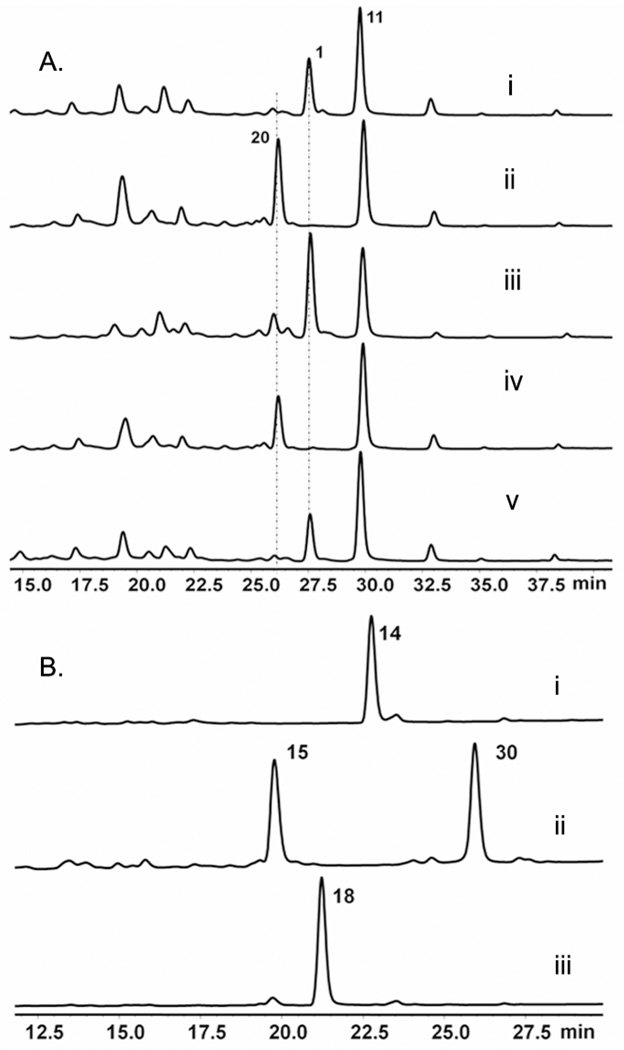

From these studies, two genes with unknown functions were identified as likely to be involved in the biosynthesis of AIB. Knocking out of either tqaM or tqaL led to the production of the same shunt product 20 (m/z = 504), which matches the mass of, and is confirmed by NMR to be nortryptoquialanine (or tryptoquialanine B) (Figure 5A trace ii and trace iv, Table S3, Figure S11). Therefore, it appears these mutants are blocked in the synthesis of AIB, and TqaB instead selected l-alanine leading to the synthesis of 20. Hence, the downstream enzymes that convert 18 to 1 are nonspecific towards the C15 gem-dimethyl. To prove that the ΔtqaL and ΔtqaM mutants are indeed blocked in AIB synthesis, we supplemented the mutant cultures with 1.5 mM AIB. As expected, production of 1 was restored to wild type levels in both mutants, thereby establishing TqaL and TqaM are essential for the de novo AIB synthesis in P. aethiopicum (Figure 5A trace iii and trace v).

Figure 5.

Identification of tqa genes that are likely involved in the biosynthesis of AIB. (A) Extract from the following strains that produced nortryptoquialaine 20 are shown here. Trace i: ΔgsfA; trace ii: ΔgsfA/ΔtqaL; trace iii: ΔgsfA/ΔtqaL supplied with 1.5 mM AIB; trace iv: ΔgsfA/ΔtqaM; trace v: ΔgsfA/ΔtqaM supplied with 1.5 mM AIB demonstrating restoration of biosynthesis of 1. (B) In vivo feeding of 120 µM 14 to trace i: BAP1 strain (no enzyme overexpression control); trace ii: BAP1 expressing TqaH; and trace iii: BAP1 expressing TqaB and TqaH and supplemented with 1.5 mM AIB.

To further prove AIB is involved in the biosynthesis of 1, we aimed to reconstitute the conversion of 14 to 18 using an E. coli strain overexpressing TqaB and TqaH, and supplemented with AIB. The tqaH and tqaB cDNA were amplified with reverse-transcription (RT)-PCR and both genes were cloned into pCDFDuet™-1 vector for expression in BAP1.35 After induction with IPTG and culturing overnight at 16°C, 14 was added to a final concentration of 120 µM and the culture was extracted with ethyl acetate after 2 hour. When TqaH was expressed alone, in vivo conversion of 14 to an oxidized product, likely 15, was observed; along with a new compound that has mass consistent with a possible crosslinked dimer 30 (Figure 5B, Figure S19). Formation of the dimer was previously observed in the in vitro reaction containing 14 and Af12060, and our result here further verifies the function of TqaH as analogous to Af12060 (Scheme 3).24 When both TqaB and TqaH were overexpressed in E. coli, along with supplementation with 1.5 mM AIB and 14, complete oxidation followed by near complete acylation with AIB to yield 18 was observed. Excluding AIB led to the accumulation of 19, further confirming the origin of the gem-dimethyl in 1.

Tailoring Enzymatic Reactions Leading to Synthesis of 1

Analysis of the extract from the single gene knockout strains (in the background of ΔgsfA) shown in Table 1 also allowed us to assign functions to the remaining enzymes in the gene cluster, of which most are suggested to be involved in the conversion of 18 to 1 (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4.

Proposed enzymatic steps that convert 18 to 1

The accumulation of 18 in the ΔtqaG knockout mutant suggests that TqaG is immediately involved in transforming 18 en route towards 1. A BLAST search identified that TqaG has a FAD-binding site and belongs to the berberine bridge enzyme (BBE) superfamily. The BBE is proposed to initiate the oxidative cyclization of the N-methyl moiety of (S)-reticuline via the formation of a methylene iminium ion that undergoes subsequent ring closure to form the berberine bridge carbon, C-8, of (S)-scoulerine.36 Therefore, we propose that TqaG might play a possible role in the 2-electron oxidation of the pyrazinone ring of 18 to yield the α-imine intermediate 21. Hydrolysis of 21 yields the imino acid 22, which can be rapidly converted to the ketone 23 upon nucleophilic attack by water at C27. Alternatively, the pyrazinone ring of 18 may be hydrolyzed to yield the C27 free amine, which can then be transaminated by a pyridoxal-5'-phosphate (PLP)-dependent enzyme to afford 23. Several lines of reasoning however, make the second pathway unlikely: 1) no enzyme bearing resemblance to a possible transaminase is observed in the gene cluster; 2) hydrolysis of the highly stable pyrazinone ring without oxidation is difficult and should result in rapid recyclization to afford the starting compound 18; and 3) the homolog of TqaG in the pathway of 7, Af12070, has been proposed to initiate the intramolecular cyclization of 7 towards fumiquinazoline C and D via oxidation of the same carbon of the pyrazinone ring (B.D.A., C.T.W. unpublished results).

TqaI is similar to trypsin-like serine proteases present in insects (e.g. >30% identity to the homologs in the dust mite Dermatophagoides farinae).37 A BLAST search using TqaI matched to only three fungal homologs (in A. clavatus, A. terreus and Gibberella zeae). The tqaI homolog in A. clavatus (ACLA_017930) is clustered together with the other tqa homologs in the genome, but absent in the gene cluster of 7 (Figure S3). Thus, it is likely that TqaI and ACLA 017930 play a common role in biosynthesis of 1 and 2 following formation of the pyrazinoquinazoline scaffold. From the ΔgsfA/ΔtqaI knockout strain, a compound (m/z = 476) that is most likely to be 23 was isolated (Figure S12). Upon purification of 23 by reverse-phase HPLC, the compound rapidly dehydrated to form the keto-lactone 24 (m/z =458). NMR characterization of 24 revealed the appearance of signals that correspond to an aliphatic ketone at δ=195.2 ppm (Table S6, Figure S14). Thorough 2D NMR confirmed the structure of 24 to be that of deoxynortryptoquialanone, in which the bridging spirolactone is installed. These evidences therefore suggest that TqaI is likely an accessory enzyme in the enzymatic lactonization of 23 to produce 24, a reaction that may also proceed spontaneously. Indeed, the ΔgsfA/ΔtqaI strain continued to produce 1 as shown in Figure 5; and the combined level of 23 and 1 in this strain is near the titer of 1 in the wild type strain.

TqaE belongs to class A flavoprotein monooxygenases and shares moderate similarity to the characterized TqaH (39% identity) and Af12060 (35% identity). Recently, a pair of TqaE/TqaH homologs (NotB/NotI) were identified in the notoamide gene cluster (both shared 45% identity to TqaE), which were proposed to catalyze a 2,3-epoxidation and a N-hydroxylation of the tryptophan-derived indole ring to form the final notoamide A.15 Indeed, deoxynortryptoquialanone 24 was also isolated from the ΔgsfA/ΔtqaE strain together with a tryptoquialanine-like compound 28 (m/z = 502). Compared to that of 1, the NMR signals of 28 are nearly identical but with the loss of the N-hydroxyl signal at δ = 7.95 ppm and appearance of a new NH signal at δ = 3.18 ppm (Table S7, Figure S17). Based on the NMR information, 28 is assigned to be deoxytryptoquialanine as shown in Scheme 4. The isolation of 24 and 28 are consistent with the predicted N-hydroxylation function of TqaE. While the exact timing of the hydroxylamine formation is not known, isolation of the ketone 24 suggests that N-oxidation of 24 to 25 may take place immediately following spirolactone formation. The high titer of 28 also indicates that the remaining tailoring steps in the tqa pathway can function in the absence of N-hydroxylation.

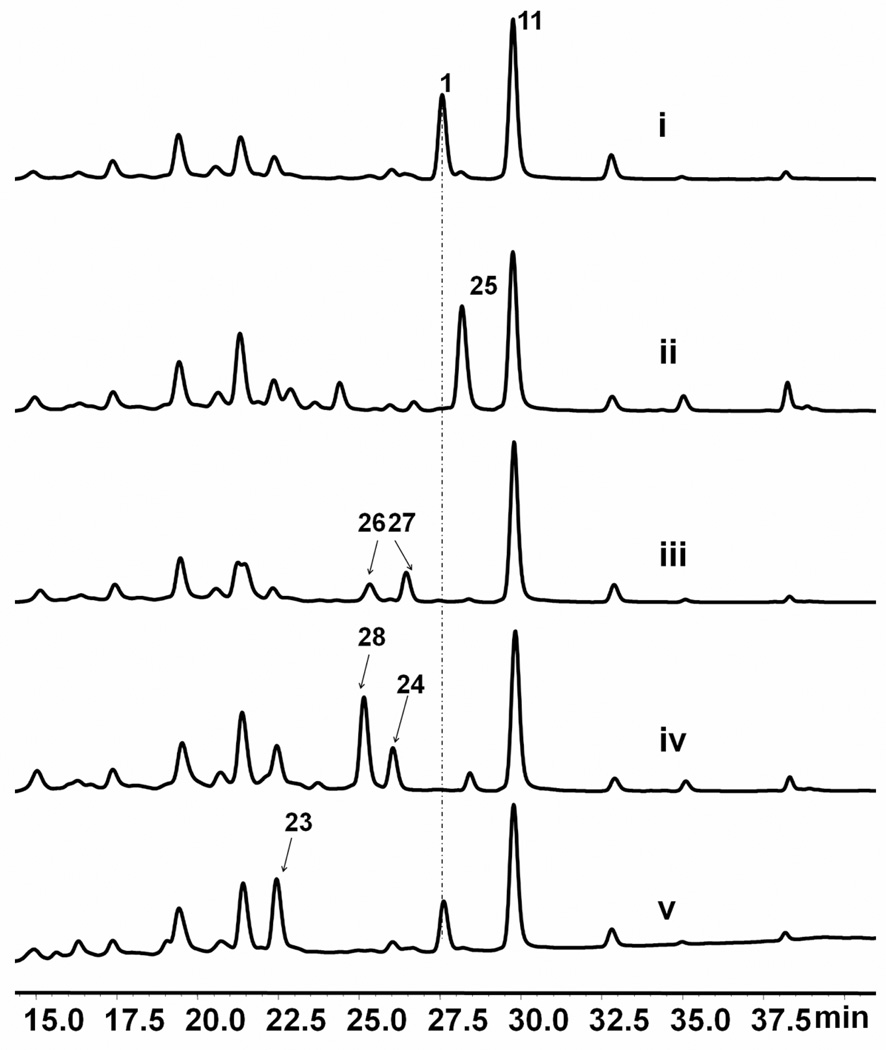

Formation of 1 from 25 requires the stereospecific reduction and acetylation of the C27 ketone. The most likely enzyme candidate in the tqa gene cluster for the ketoreduction is TqaC, which is homologous to putative NADPH-dependent short chain dehydrogenases. Inactivation of TqaC should therefore lead to accumulation of 25 in the culture extract. As expected, the ΔgsfA/ΔtqaC strain produced a single shunt product with mass (m/z = 474) and NMR data consistent with that of tryptoquialanone 25 (Figure 6, Table S6). Interestingly, 27-epi-isomers of 2 and 4 have been isolated from Corynascus setosus.38,39 Based on the deduced biosynthetic pathway of 1 and the role of TqaC, the stereochemical difference at position C27 between 2/4, and the corresponding epimers can be attributable to the different stereospecificity of the ketoreductase tqaC homologs in A. clavatus (ACLA_061530) and in C. setosus.

Figure 6.

The remaining steps of 1 biosynthesis as elucidated from the single gene knockout studies. Trace i: ΔgsfA; trace ii: ΔgsfA/ΔtqaC; trace iii: ΔgsfA/ΔtqaD; trace iv: ΔgsfA/ΔtqaE; and trace v: ΔgsfA/ΔtqaI;

Finally, in the ΔgsfA/ΔtqaD strain in which putative acetyltransferase TqaD is inactivated, two metabolites 26 and 27 that have masses (m/z = 476) consistent with the TqaC-catalyzed ketoreduction of 25 were observed (Figures S15 and S16). 26 and 27 existed in equilibrium during extraction and purification, which prevented NMR characterization of individual compounds. However, this equilibrium is expected for a C27-reduced and unacetylated intermediate, as the interconversion between the spirolactone 26 (γ-lactone) and the oxazinoquinazoline 27 (δ-lactone) should take place readily under aqueous conditions. To examine the acetyltransfer reaction in more detail, we overexpressed and purified the hexahistidine tagged TqaD from BL21 (DE3). When incubated with a mixture of 26 and 27 purified from ΔgsfA/ΔtqaD and acetyl-CoA, formation of 1 was readily observed (Figure S4). Similarly when incubated with 1 and assayed for the reverse hydrolysis reaction with 20 µM TqaD, we were able to detect the formation of both 26 and 27. In both assays, we also observed the formation of a new compound 29 that has the mass (m/z = 494) corresponding to the ring opened form of 26 and 27 (Figure S18). When extracted under strong acid conditions (5% TFA), 29 can be nearly completely lactonized into 26 and 27. Acetylation of 26 by TqaD to yield 1 is therefore the last step in the tqa pathway and is critical to prevent opening of the connecting spirolactone ring.

The only remaining gene that has not been assigned a putative function is tqaF, which encodes an enzyme belonging to the haloacid dehalogenase superfamily. The ΔgsfA/ΔtqaF strain continued to synthesize 1 at the same level as the wild type, which indicates that this enzyme may not be essential in the proposed pathway.

DISCUSSION

In work reported in this paper, we have identified a gene cluster from P. aethiopicum that is involved in the biosynthesis of the tremorgenic mycotoxin tryptoquialanine 1. The chemical logic and enzymatic machinery for generation of the architecturally complex tryptoquialanine peptidyl alkaloid scaffold from simple building blocks is revealed. By systematically inactivating every gene (15 genes total, except the transporter-encoding tqaJ) in the cluster, followed by isolation and characterization of the intermediates, we were able to establish the enzymatic sequence of the pathway. Four amino acids, two of them nonproteinogenic (anthranilate, AIB), are utilized by two nonribosomal peptide synthetase enzymes (TqaA and TqaB) that between them contain four modules, one for each building block activated and incorporated in an identical fashion to that of the pyrazinoquinazoline 7. Notably, an AIB-utilizing NRPS module (TqaB) has been reconstituted in vivo, along with identification of two putative enzymes (TqaM and TqaL) of unknown functions that are involved in the synthesis of this unnatural amino acid. The oxidative annulation of the AIB moiety onto the indole ring derived from the tryptophan building block is a particularly intriguing synthetic sequence.

P. aethiopicum is closely related to the penicillin-producing P. chrysogenum, whose genome has been sequenced,40 but both species produce distinct secondary metabolites.18 As one of the demonstrations, we previously showed that comparative genomics can be a useful tool to narrow down the biosynthetic genes responsible for production of a particular metabolite by exclusion of orthologous genes.29 The structural similarities between 1 and 2 suggest that homologous genes are likely involved in their biosynthesis. Using a similar strategy coupled with a genome-wide search of common NRPSs in P. aethiopicum and A. clavatus,41 which produces 2, we were able to pinpoint the trimodular NRPS TqaA and single module NRPS TqaB, and subsequently confirm their involvement in biosynthesis of 1 by targeted gene deletion. The observation of conserved syntenic regions flanking the tqa gene cluster when compared to the corresponding genetic locus in P. chrysogenum, is akin to the vrt and gsf loci in the previous study.29

The corresponding tqa homologs in the A. clavatus genome that are predicted to be involved in the biosynthesis of 2 were identified via BLAST search (Table 1, Figure S3). As in tqa cluster, the corresponding homologs for tqaA, tqaB, tqaE, tqaG, tqaH, and tqaI are clustered in the A. clavatus genome. Interestingly, there are several genes in the putative tqv cluster for 2 that are not clustered together with the NRPS genes but fall on a separate genomic scaffold. Specifically, the homologs for the ketoreductase (tqvC) and acetyltransferase (tqvD) are adjacent to each other and fall on the genomic scaffold 1099423829796. The corresponding A. clavatus homologs for tqaL and tqaM are also located next to each other on the same genomic scaffold as tqvC and tqvD, but the two pairs are located 440 kbp apart. Similar fragmentation of secondary metabolic gene clusters has also been observed in the pathway for dothistromin, a mycotoxin that is structurally similar to the aflatoxin intermediate versicolorin A.42 The presence of repeating sequences in the tqa gene cluster may suggest recent recombination or horizontal gene transfer events, which brought the genes in the tqa pathway into proximity. The clustering of tqa genes in the P. aethiopicum genome therefore presents an excellent opportunity to study the function of individual genes in the pathway.

Initial examination of the peptide linkages in 1 suggested that the amino acids may be assembled in the order of alanine or pyruvic acid, anthranilic acid and tryptophan, followed by the lactonization and release of the tripeptide from a trimodule NRPS. N-acylation of the indole ring with alanine/AIB could follow thereafter. However, the identification of TqaA as a trimodular NRPS with shared domain architecture and sequence similarity to Af12080 that synthesizes 14 (Figure S3), strongly indicates that 14 could be a common intermediate for both pathways. The knockout of tqaH confirmed that 14 is indeed the common intermediate and the formation of the spirolactone in 1 therefore requires opening of the pyrazinone ring, which partially masked the biosynthetic origin of 1. Furthermore, identification of 14 as the authentic intermediate demonstrated that the TqaA trimodular NRPS utilizes l-Ala instead of pyruvic acid. Other homologous genes shared by the two gene clusters are the tqaB, tqaH and tqaG. From the corresponding knockout studies, the roles of TqaB and TqaH are indeed consistent with those corresponding homologs involved in the synthesis and tailoring of 7. The isolation of 18 from ΔgsfA/ ΔtqaG mutant suggests that TqaG is the immediate oxidative tailoring enzyme in the pathway. The intriguing stereochemical difference between 18 and 7 across the C2 and C3 positions of the indole ring may be attributed to the functional difference between TqaB and Af12050. Whereas 7 contains the anti configuration that would be expected from epoxide opening by the free amine group of alanine, the syn addition in 18 points to a mechanism in which the 3-hydroxyiminium cation 16 is the true intermediate for nucleophilic attack of the TqaB-activated α-amino group on the iminium ion to yield 17 (Scheme 3). The nucleophilic nitrogen on the dearomatized indole ring presumably then attacks the aminoacyl-TqaB thioester to form the 6-5-5 imidazoindolone scaffold.

By a combination of genetic and biochemical means, we determined the gem-dimethyl moiety in 1 is incorporated via the activation of the unnatural amino acid AIB by the monomodular NRPS TqaB. Gene deletion of tqaM and tqaL abolished the production of AIB, and TqaB instead activated L-Ala to produce 20. We therefore propose that TqaM and TqaL are responsible for the production of AIB in tqa gene cluster. Although AIB is a commonly found amino acid constituent of many fungal secondary metabolites, the enzymatic basis for its biosynthesis is not known. BLAST search of the GenBank database using the amino acid sequences of TqaM and TqaL showed that homologs of these two enzymes can be found in other fungal genomes, and in most cases, adjacent to each other. These include ACLA_063360 and ACLA_063370 in A. clavatus, NCU01071 and NCU01072 in Neurospora crassa OR74A and SMAC_03146 and SMAC_03147 in Sordaria macrospora. AIB is most well-known for its abundant incorporation into a class of linear antimicrobial peptides named peptaibols (peptaibiotics), characterized prominently by high proportion of α,α-dialkylated amino acids.32,43 The membrane-modifying properties of peptaibols and their ability to form transmembrane voltage-dependent channels have attracted much interest.44,45 Since the peptaibol synthetase Tex1 homolog has been found in the sequenced Trichoderma reesei genome,46,47 we searched the JGI T. reesei v2.0 database for TqaM/L homologs. Indeed, e_gw1.17.140.1 and e_gw1.19.93.1 were identified as homologs for TqaM and TqaL respectively. However unlike in the other fungal genomes, the two homologs in T. reesei fall on different genomic scaffolds (Figure S3). The presence of TqaM and TqaL homologs in other fungal genomes maybe indicative of their undiscovered capability to produce AIB, and thus can be a useful tool for genome mining of the antimicrobial peptaibols and other AIB-containing secondary metabolites.

TqaM was predicted to have a conserved Class II aldolase domain with a Zn2+ binding site. The closest homolog of TqaM is NCU01071, which shares homology to NovR/CloR (40% and 39% identity, respectively) from the novobiocin/clorobiocin biosynthesis pathway.48 CloR has been verified to be a bifunctional non-heme iron oxygenase.49 Although a conserved DUF2257 domain was found among the TqaL and similar proteins, the function of this conserved domain is not known. Raap et al.50 reported that 2,2-dialkylglycine decarboxylase (DGD) is capable of converting AIB to acetone, and hence the PLP-dependent enzyme was also proposed to catalyze the reverse reaction, where AIB is synthesizes from acetone and CO2.46 Another possible biosynthetic mechanism might be modification of alanine with a PLP-dependent enzyme to generate the α-carbanionic species to attack the electrophilic methyl group of S-adenosylmethionine. However, neither TqaM nor TqaL contain the required PLP or SAM (S-adenosylmethionine) binding domains. Therefore, the functions of TqaM and TqaL cannot be predicted at this point and is the subject of further investigations. It is also to be determined if TqaM/L homologs are involved in biosynthesis of other α,α-dialkylated amino acids, such as isovaline (IVA).

Homology modeling and analysis of the putative substrate binding pockets of the TqaB and Af12050 A-domains provides a means to rationalize the observed differences in substrate specificities (Figure S5). The key change appears to be at position 4 (Pos4) of the 10 AA code, in which the bulkier methionine in TqaB is modeled to favorably contact both the Pos2 Leu and the pro-R methyl of 2-AIB. In Af12050 the Pos4 residue is changed to valine. The shorter side chain length of Val compared to Met allows for an alternate conformation of the Pos2 Leu, in this conformation the side chain would make favorable contacts with l-Ala but clash with the pro-R methyl group of 2-AIB, therefore resulting in the preferential binding and activation of L-Ala in the biosynthesis of 7. However, the 10AA code of TqaB-A domain shares low similarities to the proposed AIB activation A domains in Tex1, which suggests that the AIB-activating A domains in TqaB/TqvB and those in other peptaibol synthetases, such as ampullosporin synthetase,51 and alamethicin synthetase,52 may have evolved separately.

The conversion of the tricyclic fumiquinazoline F 14 scaffold to the bicyclic framework in the tremorgens 1 and 2 with installation of the γ-spirolactone is an intriguing set of chemical transformations. The scaffold of 14 is first elaborated to an epimer of 7 in an annulation of the indole ring derived from tryptophan. The annulation can use l-alanyl thioester linked to the pantetheinyl arm of the NRPS protein TqaB to produce 19, but TqaB prefers the unusual AIB yielding 18. This imidazolindolone-containing intermediate is then subjected to a series of steps which take apart the pyrazinone ring of the tricyclic quinazoline framework. It appears that the process starts with oxidation of the secondary amine to the imine and that the C27-N10 bond is then fragmented in an unusual manner to yield formally the imine and acid components. The imine can hydrolyze to the ketone, observed as an intermediate 24. N-hydroxylation requires opening of the pyrazinone ring since no N16-hydroxylated pyrozinoquinazoline intermediate was obtained. Reduction of the ketone 25 to alcohol 26 then sets up the possibility of an equilibrium between the dihydroxy acid, the spiro-γ-lactone, and the δ-lactone, all of which are detectable in specific knockout mutants. Regioselective acetylation of the C27-OH by the acetyltransferase TqaD fixes the final product 1 with the γ-lactone ring. Whether the ring-opening of the oxidized pyrazine ring in 21 from TqaG action is by net hydrolysis or involves intramolecular capture of 21 by the OH at C3 of the imidazoindolone moiety to yield 24 directly is not yet known but would provide a driving force for fragmentation of 21. Note that the nucleophilic-OH for spirolactone formation in 25 was introduced by oxidation/annulation of the indole side chain that happened at the stage of annulation of 14. Conversion of 18 to 26 with a dramatically rearranged molecular architecture occurs by cryptic redox processes: regiospecific oxidation of the secondary amine in the quinazoline framework of 18 and then rereduction of the carbonyl after imine hydrolysis and spirolactone formation.

Given the remarkable morphing of the fumiquinazoline F scaffold 14 to the rearranged framework of the tryptoquialanine scaffold 1 with the above annulation and also γ-spirolactone formation, the pathway is remarkably short and efficient. Four redox enzymes are called into play: three of them (TqaH,G,E, acting in that order) contain FAD, the other (TqaC) utilizes NADPH in a conventional ketone to alcohol reduction of 25 to 26. The flavoenzymes were proposed to carry out epoxidation of the indole side chain in 14 (TqaH), oxidation of the secondary amine linkage to cyclic imine in the pyrazinone ring of the pyrazinoquinazoline(TqaG) as the initiating step in fragmentation, and N-hydroxylation of the imidazoindolone (TqaE: 24 to 25), respectively. These transformations underscore the versatility of the FAD coenzyme for a wide chemical range of redox transformations by these biosynthetic enzymes. The detailed mechanisms of these novel enzymatic reactions are currently under investigation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

P. aethiopicum, IBT 5753, was obtained from the IBT culture collection (Kgs. Lyngby, Denmark). All other chemicals and solvents were purchased from either Sigma-Aldrich or Fisher Scientific unless otherwise noted.

Spectroscopic Analysis

The NMR identification of compounds was performed on a Bruker ARX500 at the University of California Los Angeles Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry NMR facility. LC/MS spectra were obtained on a Shimadzu 2010 EV liquid chromatography mass spectrometer using positive and negative electrospray ionization and a Phenomenex Luna 5 µm, 2.0 mm × 100 mm C18 reverse-phase column. Samples were separated on a linear gradient of 5 to 95% CH3CN in water (0.1% formic acid) for 30 min at a flow rate of 0.1 mL/min followed by isocratic 95% CH3CN in water (0.1% formic acid) for another 15 min.

Bioinformatic Analysis

The 454-generated partial genomic sequencing data of P. aethiopicum is the same version as previously published,29 and was formatted into a local database for BLAST searches. Gene predictions were performed using the FGENESH online server (Softberry) and manually checked by comparing with homologous gene/proteins in the GenBank database. Functional domains in the translated protein sequences were predicted using Conserved Domain Search (NCBI). The amino acid sequences of TqaB and other NRPS adenylation domains were submitted to NRPSpredictor for automated extraction of specificity-defining residues as the 10AA code.33 The sequence of the tqa gene cluster has been submitted to GenBank with the accession number HQ591508.

X-ray Crystallographic Analysis

1 was crystallized from a mixture of methylene chloride/heptanes and 18 was obtained from the acetone/methanol mixture. X-ray diffraction was performed by the University of California Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry crystallography facility. Additional details can be found in the supplementary methods. The crystal structures of 1 and 18 are deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre and allocated the deposition numbers CCDC 800378 and 800379, respectively.

Construction and Screening of Fosmid Library

Fosmid library of P. aethiopicum was constructed using the CopyControl™ Fosmid Library Production Kit (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, WI) following the manufacturer’s instruction. Screening by direct colony PCR was carried out using GoTaq polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI). Initial screening was performed using pools of ~200 colonies and narrowed down to single colonies. Positive clones identified were sent for fosmid end-sequencing and primer walking. Adjacent contigs were identified from the P. aethiopicum genomic database using local BLAST search of the partial fosmid sequences and assembled by pairwise alignment.

Fungal Transformation and Gene Disruption in P. aethiopicum

Polyethylene glycolmediated transformation of P. aethiopicum was performed essentially as described previously.29 The homologous regions flanking the resistant marker were increased to ~2 kb and other steps for construction of fusion PCR knockout cassettes containing the bar or zeocin gene were performed as described elsewhere.53 Fusion PCR products were sequenced before using for transformation. ~7 µg DNA was gel-purified for each transformation. The bar gene with the trpC promoter was amplified from the plasmid pBARKS154,55, which was obtained from the Fungal Genetics Stock Center (FGSC). The zeocin gene with the gpda promoter was amplified from the plasmid pAN8-1 (a gift from P. J. Punt, Institute Biology Leiden).56 Glufosinate used for the selection of bar transformants was prepared as described previously.29 Miniprep genomic DNA from P. aethiopicum transformants was used for PCR screening of gene deletants and was prepared as described elsewhere for A. nidulans.57 Primers used for amplification of fusion PCR products and screening of transformants, are listed in Table S2. Approximately 50 glufosinate-/zeocin- resistant transformants were picked and screened with PCR using a bar/zeocin gene primer and primers outside of the deletion cassette.

Chemical Analysis and Compound Isolation

For small-scale analysis, the P. aethiopicum wild-type and transformants were grown in stationary YMEG liquid culture (4 g/l yeast extract, 10 g/l malt extract, 5 g/l glucose and 16 g/l agar) for 4 days at 25°C. The cultures were extracted with equal volume of ethyl acetate and evaporated to dryness. The dried extracts were dissolved in methanol for LC-MS analysis. For large-scale analysis, the ethyl acetate (EA) extract from a two liters stationary liquid culture of each mutant was evaporated to dryness and partition between EA/H2O twice. After evaporation of the organic phase, the crude extracts were separated by silica chromatography. The purity of each compound was checked by LC-MS and the structure was confirmed by NMR.

Expression and Purification of Recombinant Enzymes

TqaB and TqaD cDNA were cloned into a pET28 vector with an N-terminal hexahistidine tag and expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) strain. The transformant was cultured in 500 mL LB medium containing 35 mg/L kanamycin at 37°C to optical density (OD600) value of 0.4~0.6. Protein expression was induced with 0.1 mM IPTG and the subsequent expression was performed at 16°C overnight. Cells were collected by centrifugation (2000 g, 4°C, 15 min), resuspended in 30 ml Buffer A (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 2 mM DTT, 2 mM EDTA), and lysed by sonication. Cell debris and insoluble proteins were removed by centrifugation (20,000 g, 4°C, 1 hr). To the cleared cell lysate, excess amount (0.5 ml) of Ni-NTA resin (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) was added to each sample. The TqaB protein was then purified using a step gradient of Buffer A with increasing concentration of imidazole (10 and 20 mM) and was eluted with 5 mL Buffer A containing 250 mM imidazole. Protein purity was qualitatively assessed by SDS-PAGE and concentration was quantitatively determined by the Bradford protein assay using bovine serum albumin as the standard.

ATP-[32P]PPi exchange assay for TqaB

Reactions (100 µL) contained 2 mM ATP, 2 mM MgCl2, 3 mM Na4[32P]PPi (0.2 µCi), 2 µM TqaB, and 2 mM amino acid substrate in buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl (pH7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 5mM TCEP, and 5% glycerol). Enzyme was added last to initiate the reactions and, following a 60 min incubation at 25 °C, the reactions were stopped by adding 400 µL of a quench solution (1.6% (w/v) activated charcoal, 100 mM sodium pyrophosphate, and 3.5% perchloric acid in water). The charcoal was collected by centrifugation, washed twice with quench solution minus charcoal, and the absorbed radioactivity detected by liquid scintillation counting.

E. coli Mediated Biotransformation of 14 to 18

TqaH cDNA was amplified by RT-PCR using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Promega) and AccuPrime™ Pfx DNA polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA); and was cloned into pCDFDuet™-1 (EMD Chemicals, Gibbstown, NJ) and transformed into E. coli BAP1 strain35. The transformant with the TqaB and TqaH dual-expression plasmid was grown in LB medium at 37 °C to an OD600 of 0.4–0.6, at which time the cultures were cooled to 16 °C, and then induced with 0.1 mM IPTG at 250 rpm and grown at 16°C for overnight. To increase cell density, the E. coli cells were concentrated 10-fold before addition of substrates. A 10 mL aliquot of each culture was collected by centrifugation (4 °C, 2000 g, 10 min). The cell pellet was gently resuspended in 1 mL of medium supernatant, followed by addition of 6 µL 14 (20 mM stock) to a final concentration of 120 µM. The small cultures were then shaken at 300 rpm at 25 °C for 2 hrs. For product detection, 100 µL of cell culture was collected and extracted with 500 µL of ethyl acetate. The organic phase was separated, evaporated to dryness, redissolved in methanol, and then subjected to LC-MS analysis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work is supported by NIH Grant 1R01GM092217 to Y. T.; 1F32GM090475 to B. D. A.; and 1R01GM49338 to C. T. W. We thank Prof. Neil Garg for helpful discussions and Prof. Peter J. Punt for the generous gift of the plasmid pAN8-1. We thank Wei Xu for advice on compound crystallization. We thank Dr. Saeed I. Khan at University of California Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry crystallography facility for solving the X-ray structures. Ian McRae is thanked for his help as an undergraduate research assistant.

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE: Additional experimental procedures and compound characterizations. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cole RJ. J. Food Prot. 1981;44:715. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-44.9.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans T, Gupta R. In: Veterinary toxicology: basic and clinical principles. Gupta R, editor. New York: Academic Press; 2007. p. 1004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steyn P, R V. Fortschr. Chem. Org. Naturst. 1985;48:1. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-8815-6_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D' Yakonov A, Telezhenetskaya M. Chem. Nat. Compd. 1997;33:221. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knaus HG, McManus OB, Lee SH, Schmalhofer WA, Garciacalvo M, Helms LMH, Sanchez M, Giangiacomo K, Reuben JP, Smith AB, Kaczorowski GJ, Garcia ML. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5819. doi: 10.1021/bi00185a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selala MI, Daelemans F, Schepens PJC. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 1989;12:237. doi: 10.3109/01480548908999156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao Y, Peter AB, Baur R, Sigel E. Mol. Pharmacol. 1989;35:319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rabindran SK, Ross DD, Doyle LA, Yang WD, Greenberger LM. Anticancer Res. 2000;60:47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dowd PF, Cole RJ, Vesonder RF. J. Antibiot. 1988;41:1868. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.41.1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayashi H. Recent Res. Dev. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1998;2:511. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayashi H, Asabu Y, Murao S, Nakayama M, Arai M. Chem. Express. 1993;8:177. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saikia S, Nicholson MJ, Young C, Parker EJ, Scott B. Mycol. Res. 2008;112:184. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato N, Suzuki H, Takagi H, Asami Y, Kakeya H, Uramoto M, Usui T, Takahashi S, Sugimoto Y, Osada H. Chembiochem. 2009;10:920. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steffan N, Grundmann A, Yin WB, Kremer A, Li SM. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009;16:218. doi: 10.2174/092986709787002772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding YS, de Wet JR, Cavalcoli J, Li SY, Greshock TJ, Miller KA, Finefield JM, Sunderhaus JD, McAfoos TJ, Tsukamoto S, Williams RM, Sherman DH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:12733. doi: 10.1021/ja1049302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clardy J, Springer JP, Buchi G, Matsuo K, Wightman R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975;97:663. doi: 10.1021/ja00836a045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ariza MR, Larsen TO, Petersen BO, Duus JO, Barrero AF. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2002;50:6361. doi: 10.1021/jf020398d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frisvad JC, Samson RA. Studies in Mycol. 2004:1. doi: 10.3114/sim.2011.69.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong SM, Musza LL, Kydd GC, Kullnig R, Gillum AM, Cooper R. J. Antibiot. 1993;46:545. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.46.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takahashi C, Matsushita T, Doi M, Minoura K, Shingu T, Kumeda Y, Numata A. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1995;1:2345. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finking R, Marahiel MA. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2004;58:453. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stack D, Neville C, Doyle S. Microbiology-Sgm. 2007;153:1297. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/006908-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ames BD, Walsh CT. Biochemistry. 2010;49:3351. doi: 10.1021/bi100198y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ames BD, Liu XY, Walsh CT. Biochemistry. 2010;49:8564. doi: 10.1021/bi1012029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiao RH, Xu S, Liu JY, Ge HM, Ding H, Xu C, Zhu HL, Tan RX. Org. Lett. 2006;8:5709. doi: 10.1021/ol062257t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larsen TO, Petersen BO, Duus JO. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001;49:5081. doi: 10.1021/jf010345g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Springer JP. Tetrahedron Lett. 1979:339. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamazaki M, Okuyama E. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1979;27:1611. doi: 10.1248/cpb.27.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chooi YH, Cacho R, Tang Y. Chem. Biol. 2010;17:483. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yin WB, Grundmann A, Cheng J, Li SM. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807606200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang S, Xu Y, Maine EA, Wijeratne EM, Espinosa-Artiles P, Gunatilaka AA, Molnar I. Chem. Biol. 2008;15:1328. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wiest A, Grzegorski D, Xu BW, Goulard C, Rebuffat S, Ebbole DJ, Bodo B, Kenerley C. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:20862. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201654200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rausch C, Weber T, Kohlbacher O, Wohlleben W, Huson DH. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5799. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sattely ES, Fischbach MA, Walsh CT. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2008;25:757. doi: 10.1039/b801747f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pfeifer BA, Admiraal SJ, Gramajo H, Cane DE, Khosla C. Science. 2001;291:1790. doi: 10.1126/science.1058092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kutchan TM, Dittrich H. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:24475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.24475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kawamoto S, Mizuguchi Y, Morimoto K, Aki T, Shigeta S, Yasueda H, Wada T, Suzuki O, Jyo T, Ono K. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1454:201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fujimoto H, Negishi E, Yamaguchi K, Nishi N, Yamazaki M. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1996;44:1843. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mhaske SB, Argade NP. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:9787. [Google Scholar]

- 40.van den Berg MA, et al. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:1161. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fedorova ND, et al. PLos Genet. 2008;4 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang S, Schwelm A, Jin H, Collins LJ, Bradshaw RE. Fungal Genet Biol. 2007;44:1342. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bruckner H, Becker D, Gams W, Degenkolb T. Chem. Biodivers. 2009;6:38. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200800331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rebuffat S, Duclohier H, Auvin-Guette C, Molle G, Spach G, Bodo B. FEMS Immunol. Microbiol. 1992;105:151. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb05886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sansom MSP. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 1991;55:139. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(91)90004-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kubicek CP, Komon-Zelazowska M, Sandor E, Druzhinina IS. Chem. Biodivers. 2007;4:1068. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200790097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Daniel JFD, Rodrigues E. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2007;24:1128. doi: 10.1039/b618086h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pojer F, Li SM, Heide L. Microbiology. 2002;148:3901. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-12-3901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pojer F, Kahlich R, Kammerer B, Li SM, Heide L. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:30661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303190200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raap J, Erkelens K, Ogrel A, Skladnev DA, Bruckner H. J. Pept. Sci. 2005;11:331. doi: 10.1002/psc.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reiber K, Neuhof T, Ozegowski JH, Von Dohren H, Schwecke T. J. Pept. Sci. 2003;9:701. doi: 10.1002/psc.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mohr H, Kleinkauf H. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1978;526:375. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(78)90129-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Szewczyk E, Nayak T, Oakley CE, Edgerton H, Xiong Y, Taheri-Talesh N, Osmani SA, Oakley BR. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:3111. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pall M, Brunelli J. Fungal Genet. Newsl. 1993;40:59. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mullaney EJ, Hamer JE, Roberti KA, Yelton MM, Timberlake WE. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1985;199:37. doi: 10.1007/BF00327506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Punt PJ, Dingemanse MA, Kuyvenhoven A, Soede RDM, Pouwels PH, Vandenhondel C. Gene. 1990;93:101. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90142-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chooi YH, Stalker DM, Davis MA, Fujii I, Elix JA, Louwhoff S, Lawrie AC. Mycol. Res. 2008;112:147. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.